Abstract

BACKGROUND

Diagnostic and treatment delay in depression are due to physician and patient factors. Patients vary in awareness of their depressive symptoms and ability to bring depression-related concerns to medical attention.

OBJECTIVE

To inform interventions to improve recognition and management of depression in primary care by understanding patients’ inner experiences prior to and during the process of seeking treatment.

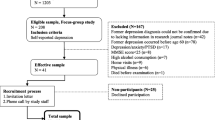

DESIGN

Focus groups, analyzed qualitatively.

PARTICIPANTS

One hundred and sixteen adults (79% response) with personal or vicarious history of depression in Rochester NY, Austin TX and Sacramento CA. Neighborhood recruitment strategies achieved sociodemographic diversity.

APPROACH

Open-ended questions developed by a multidisciplinary team and refined in three pilot focus groups explored participants’ “lived experiences” of depression, depression-related beliefs, influences of significant others, and facilitators and barriers to care-seeking. Then, 12 focus groups stratified by gender and income were conducted, audio-recorded, and analyzed qualitatively using coding/editing methods.

MAIN RESULTS

Participants described three stages leading to engaging in care for depression — “knowing” (recognizing that something was wrong), “naming” (finding words to describe their distress) and “explaining” (seeking meaningful attributions). “Knowing” is influenced by patient personality and social attitudes. “Naming” is affected by incongruity between the personal experience of depression and its narrow clinical conceptualizations, colloquial use of the word depression, and stigma. “Explaining” is influenced by the media, socialization processes and social relations. Physical/medical explanations can appear to facilitate care-seeking, but may also have detrimental consequences. Other explanations (characterological, situational) are common, and can serve to either enhance or reduce blame of oneself or others.

CONCLUSIONS

To improve recognition of depression, primary care physicians should be alert to patients’ ill-defined distress and heterogeneous symptoms, help patients name their distress, and promote explanations that comport with patients’ lived experience, reduce blame and stigma, and facilitate care-seeking.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Kravitz RL, Epstein RM, Feldman MD, et al. Influence of patients' requests for direct-to-consumer advertised antidepressants: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:1995–2002.

Levinson W, Gorawara-Bhat R, Lamb J. A study of patient clues and physician responses in primary care and surgical settings. JAMA. 2000;284:1021–7.

Lang F, Floyd MR, Beine KL. Clues to patients' explanations and concerns about their illnesses. A call for active listening. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9:222–7.

Epstein RM, Hadee T, Carroll J, Meldrum SC, Lardner J, Shields CG. "Could this be something serious?" Physicians' responses to patients' expressions of worry and distress. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1731–9.

Barbui C, Tansella M. Identification and management of depression in primary care settings. A meta-review of evidence. Epidemiol Psichiatr Soc. 2006;15:276–83.

Young AS, Klap R, Sherbourne CD, Wells KB. The quality of care for depressive and anxiety disorders in the United States. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:55–61.

Harman JS, Edlund MJ, Fortney JC. Disparities in the adequacy of depression treatment in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55:1379–85.

Dwight-Johnson M, Sherbourne CD, Liao D, Wells KB. Treatment preferences among depressed primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:527–34.

Barney LJ, Griffiths KM, Christensen H, Jorm AF. Exploring the nature of stigmatising beliefs about depression and help-seeking: implications for reducing stigma. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:61.

Goldman LS, Nielsen NH, Champion HC. Awareness, diagnosis, and treatment of depression. J Gen Intern Med. 1999;14:569–80.

Cooper-Patrick L, Powe NR, Jenckes MW, Gonzales JJ, Levine DM, Ford DE. Identification of patient attitudes and preferences regarding treatment of depression. J Gen Intern Med. 1997;12:431–8.

Mohr DC, Hart SL, Howard I, et al. Barriers to psychotherapy among depressed and nondepressed primary care patients. Ann Behav Med. 2006;32:254–8.

Kravitz RL, Paterniti DA, Epstein R, et al. Organizational and relational barriers to depression help-seeking in primary care: Qualitative Study. Ann Fam Med. 2009.

Karasz A, Sacajiu G, Garcia N. Conceptual models of psychological distress among low-income patients in an inner-city primary care clinic. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:475–7.

Karasz A, Watkins L. Conceptual models of treatment in depressed Hispanic patients. Ann Fam Med. 2006;4:527–33.

Karasz A. Cultural differences in conceptual models of depression. Soc Sci Med. 2005;60:1625–35.

Feldman MD, Franks P, Duberstein PR, Vannoy S, Epstein R, Kravitz RL. Let's not talk about it: suicide inquiry in primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2007;5:412–8.

Rudebeck CE. General practice and the dialogue of clinical practice: On symptoms, symptom presentations, and bodily empathy. Scand J Prim Health Care. 1992;Supplement:1–87.

Epstein RM, Quill TE, McWhinney IR. Somatization reconsidered: Incorporating the patient's experience of illness. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159:215–22.

Raue PJ, Schulberg HC, Heo M, Klimstra S, Bruce ML. Patients' depression treatment preferences and initiation, adherence, and outcome: a randomized primary care study. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:337–43.

Good BJ, Good MD. The Meaning of Symptoms: A Cultural Hermeneutic Model for Clinical Practice. In: Eisenberg L, Kleinman A, eds. The Relevance of Social Science for Medicine. Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Co.; 1981:165–96.

Stoeckle JD, Barsky AJ. Attributions: Uses of Social Science Knowledge in the 'Doctoring' of Primary Care. In: Eisenberg L, Kleinman A, eds. The Relevance of Social Science for Medicine. Dordrecht, Holland: D. Reidel Publishing Co.; 1981:223–40.

Baumann LJ, Cameron LD, Zimmerman RS, Leventhal H. Illness representations and matching labels with symptoms. Health Psychol. 1989;8:449–69.

Leventhal H, Diefenbach MA, Leventhal EA. Illness cognition: Using common sense to understand treatment adherence and affect cognition interactions. Cogn Ther Res. 1992;16(2):143–63.

Safer MA, Tharps QJ, Jackson TC, Leventhal H. Determinants of three stages of delay in seeking care at a medical clinic. Med Care. 1979;17:11–29.

Karasz A. The development of valid subtypes for depression in primary care settings: a preliminary study using an explanatory model approach. J of Nerv Ment Dis. 2008;196:289–96.

Bandura A. Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:191–215.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Stages and processes of self-change of smoking: toward an integrative model of change. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51:390–5.

Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC. Transtheoretical therapy: Toward a more integrative model of change. Psychotherapy Theory, Research and Practice. 1982;19:276–88.

Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK. Linking theory, research, and practice. In: Glanz K, Lewis FM, Rimer BK, eds. Health Behavior and Health Education: Theory, Research, and Practice. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1997:19–35.

Pescosolido BA. Beyond rational choice: The social dynamics of how people seek help. Am J Sociol. 1992;97:1096.

Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? J Health Soc Behav. 1995;36:1–10.

Rochlen AB, Paterniti DA, Epstein RM, Duberstein P, Willeford L, Kravitz RL. Barriers in Diagnosing and Treating Men With Depression: A Focus Group Report. Am J Mens Health. 2009.

Bell RA, Paterniti DA, Azari R, et al. Encouraging patients with depressive symptoms to seek care: A mixed methods approach to message development. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;78:198–205.

American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV. 4th ed. Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

Andersen R, Anderson OW, Smedby B. Perception of and response to symptoms of illness in Sweden and the United States. Med Care. 1968;6:18–30.

Wittink MN, Dahlberg B, Biruk C, Barg FK. How older adults combine medical and experiential notions of depression. Qual Health Res. 2008;18:1174–83.

Lowe B, Kroenke K, Herzog W, Grafe K. Measuring depression outcome with a brief self-report instrument: sensitivity to change of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9). J Affect Disorders. 2004;81:61–6.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded with support from Grants # R01MH79387 and K24MH72756 (R. Kravitz, PI) and K24MH072712 (P. Duberstein, PI). The authors thank Tina Slee for research assistance and Dawn Case for manuscript preparation.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Kravitz has received unrestricted research grants from Pfizer during the past three years. Dr. Epstein gave two lectures on patient-physician relationships for Merck in 2009 in which no commercial products were discussed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix — Focus Group Guiding Questions

Appendix — Focus Group Guiding Questions

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Epstein, R.M., Duberstein, P.R., Feldman, M.D. et al. “I Didn’t Know What Was Wrong:” How People With Undiagnosed Depression Recognize, Name and Explain Their Distress. J GEN INTERN MED 25, 954–961 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1367-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1367-0