Abstract

Background

Racial/ethnic minorities are more likely to report receipt of lower quality of health care; however, the mediators of such patient reports are not known.

Objectives

To determine (1) whether racial disparities in perceptions of quality of health care are mediated by perceptions of being discriminated against while receiving medical care and (2) whether this association is further mediated by patient sociodemographic characteristics, access to care, and patient satisfaction across racial/ethnic groups.

Research Design

A cross-sectional analysis of a population-based sample of California adults responding to the 2003 California Health Interview Survey. Multivariable logistic regression was used to examine the relationship between perceived discrimination and perceived quality of health care after adjusting for patient characteristics and reports of access to care.

Main Results

A total of 36,831 respondents were included. African Americans (68.7%) and Asian/Pacific Islanders (64.5%) were less likely than non-Hispanic whites (72.8%) and Hispanics (74.9%) to rate their health care quality highly. African Americans (13.1%) and Hispanics (13.4%) were the most likely to report discrimination, followed by Asian/Pacific Islanders (7.3%) and non-Hispanic whites (2.6%). Racial/ethnic discrimination in health care was negatively associated with ratings of health care quality within each racial/ethnic group, even after adjusting for sociodemographic variables and other indicators of access and satisfaction. Feeling discriminated against fully accounted for the difference in low ratings of quality care between African Americans and whites, but not for other racial/ethnic minorities.

Conclusions

Patient perceptions of discrimination may play an important, yet variable role in ratings of health care quality across racial/ethnic minority groups. Health care institutions should consider how to address this patient concern as a part of routine quality improvement.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Racial and ethnic minorities in the United States are disproportionately affected by poor quality of health care.1,2 Racial/ethnic differences in access to care, receipt of needed medical care, and receipt of life-saving technologies may be the result of system-level factors or may be due to individual physician behavior. For example, patient race/ethnicity has been shown to influence physician interpretation of patients′ complaints and ultimately clinical decision-making, such as decisions to refer patients for particular treatments or procedures.3,4

Patient reports of quality of health care also demonstrate substantial racial/ethnic disparities.3-9 In a national survey, 65% of non-Hispanic white patients reported being very satisfied with the quality of health care received in the past 2 years, compared to only 56% of Hispanic and 45% of Asian patients.1 Understanding the mediators of such racial/ethnic differences in patient reports of quality is important as it may lead to solutions to address disparities in clinical quality and outcomes. Patients act and make decisions based on their perceptions, with previous studies documenting the impact of perceived quality of care on relevant medical care outcomes, such as adherence to medical advice,10 cancer screening recommendations,11 and medication regimens.10,12 Potential mediators of racial/ethnic disparities in reports of health care quality include patient perceptions of clinical interactions and access to care, as well as sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., educational level).

Discrimination during the health care process may represent a particularly important mediator of the observed racial/ethnic differences in reports of health care quality.13-15 Minority patients are more likely to report being the subject of negative attitudes during the health care process,7,10,16-20 and these feelings of discrimination may negatively impact their assessment of quality of care received. Such negative feelings may lead to decreased medication adherence and medical follow-up.12,21 While prior studies have documented a relationship between patient-reported quality of health care and reports of discrimination,22 there is little information available as to the extent to which perceived discrimination mediates racial/ethnic disparities in reports of quality of health care.

The present study used the California Health Interview Survey 2003 data to examine whether racial/ethnic disparities in perceptions of health care are mediated by (1) perceived discrimination, (2) patient sociodemographic characteristics, or (3) other measures of patient experiences of care including access to care and individual physician ratings. Our primary hypothesis was that racial/ethnic minorities would be more likely to experience discrimination in health care compared to non-Hispanic white patients and that these ratings would be associated with poorer perceptions of health care quality.

METHODS

Data Source and Study Population

Data from the 2003 California Health Interview Survey (CHIS) were analyzed. The CHIS is a random-digit dial (RDD) telephone survey of the state of California civilian, non-institutionalized population.23 Personnel from CHIS interviewed one randomly selected adult in more than 40,000 households sampled in the state. Interviews were conducted in five languages: English, Spanish, Chinese (Mandarin and Cantonese dialects), Vietnamese, and Korean. CHIS is designed to provide population estimates for California’s major racial/ethnic groups. Data were collected between August 2003 and February 2004. For the 2003 CHIS adult sample, the response rate was 60%,24 which is comparable to telephone surveys carried out by the National Center for Health Statistics.

CHIS 2003 data are weighted to account for the complex sample design and to adjust for non-response and households without telephones. CHIS 2003 estimates are consistent with 2003 California Department of Finance Population Projections of the state population.25 The sample for these analyses was restricted to adults, 18 years or older, who rated the quality of their health care in the last 12 months (N=36,831).

Variables Assessed

The outcome of interest was perceived quality of health care. Respondents were asked to rate all of the health care that they received in the past 12 months on an 11-point scale (0= worst health care possible, 10= best health care possible). Responses were recoded and dichotomized, scores in the top third of the scale (7–10) were recoded to indicate higher quality of health care (0), and the rest (0–6) were recoded to indicate lower quality of health care (1).

The primary independent variables were race/ethnicity and feeling discriminated against in health care because of race/ethnicity. Feeling discriminated against in health care because of race/ethnicity was assessed by asking respondents the question: “Has there ever been a time that you felt you would have gotten better medical care if they you had belonged to a different race or ethnic group?” (1= no, 2=yes). To assess self-reported race/ethnicity, individuals were classified as non-Hispanic white (n = 24,474), Hispanic (n = 6,368), Asian/Pacific Islander (n = 3,526), or African American (n = 2,463). Due to the small size of the sample of those who classified themselves as Native American, Native Hawaiian, or “other,” they were not included in the analyses.

Demographic, health status, and insurance status variables used in this analysis included age, gender, education level, country of birth, English language proficiency, chronic health conditions, and current insurance status. Education level was recoded into two categories: (1) some college or less vs. (2) college graduate or more. Country of birth was recoded into two categories: (1) another country vs. (2) the US. English language proficiency was recorded as (1) very well/well (high proficiency) or (2) not well/not at all (limited proficiency). Chronic health conditions were assessed by asking respondents whether they had been diagnosed with any of eight chronic health conditions (e.g., high blood pressure, diabetes, cancer; 0= health problem not reported, 1= health problem reported). Responses were summed and weighted26 to form a measure of the number of chronic health conditions (0= none, 1 = one or two chronic conditions, 2 = three or more chronic conditions). Current insurance status was recoded into two categories: (1) any insurance coverage vs. (2) no insurance.

Satisfaction with the provider was assessed by asking respondents whether they had a hard time understanding the doctor (1= no, 2= yes) and how much of a problem it was to get a personal doctor or nurse they were happy with (1= not a problem, 2= a small or big problem). Respondents′ health care access was evaluated by three questions. The first asked respondents whether or not they had a usual source of care. The next two questions asked respondents how much of a problem it had been to see a specialist over the last 12 months and how much of a problem delays in health care while waiting for approval from the health plan had been over the past 12 months. Usual source of care was recoded into two categories: (1) has a usual source of care vs. (2) does not have a usual source of care. Problems seeing a specialist and waiting for approval from the health plan over the past 12 months were recoded into two categories: (1) not a problem vs. (2) a small or big problem.

Analysis Plan

All analyses were performed with SAS Callable SUDAAN Release 8.0.2 (Research Triangle Institute, Research Triangle Park, NC) to account for the CHIS complex sampling design and to obtain proper variance estimations. The data analysis was done in four phases. First, we generated descriptive statistics for each study variable. To characterize factors associated with the outcomes of interest, we conducted bivariable analysis using chi-square tests to compare categorical variables and ANOVA tests for continuous variables. Two-tailed P values less than or equal to 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Second, we conducted multivariable logistic regression models to determine the impact of race/ethnicity and discrimination on perceived quality of care. A priori, we included in the adjusted models as covariates other possible sociodemographic predictors of quality care including education level, insurance status, and English language proficiency. We built the models adding groups of variables in a sequential manner: (1) race/ethnicity, (2) discrimination, and (3) other sociodemographic variables, including health and insurance status. Finally, we conducted stratified analyses to test four separate regression models to determine the relationship between experiences of discrimination in health care and ratings of quality of care within each racial/ethnic group, adjusting for related sociodemographic variables and other indicators of access and satisfaction. Since the frequency of perceptions of lower quality of health care is relatively high in this sample (greater than 10%), the adjusted odds ratio may exaggerate the magnitude of a risk association. Therefore, the odds ratios obtained in the logistic regression models were corrected by generating prevalence rate ratios (PR) using a method described by Zhang.27

RESULTS

Demographics

A total of 36,831 respondents were included in our main analysis; 53% were women, 68% had less than a college degree, and 67% were born in the US. Respondents were non-Hispanic white (55%), Hispanic (26%), Asian/Pacific Islander (13%) and African American (7%), reflecting the demographic composition of California.25 Table 1 shows the demographic characteristics of study respondents by race/ethnicity. Hispanic respondents were more likely to be younger, have less than a college education, and lack health insurance compared to other respondents. Asian/Pacific Islander respondents were the most likely to report being born outside the US. Both Hispanic and Asian respondents were more likely to report having limited English language proficiency compared to non-Hispanic white and African American respondents.

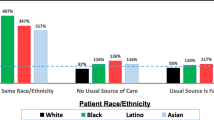

As shown in Table 1, Asian/PIs (35.5%) and African-Americans (31.3%) were more likely to report lower quality of care as compared to Hispanics (25.1%) and non-Hispanic whites (27.2%). Furthermore, African Americans (13.1%) and Hispanics (13.4%) were more likely to feel discriminated against in health care because of their race/ethnicity, followed by Asian/Pacific Islanders (7.3%) and non-Hispanic whites (2.6%).

Feeling Discriminated Against Because of Race/Ethnicity in Health Care and Ratings of Quality of Care

Table 2 presents the results of three sequential logistic regression models examining the relationship between race/ethnicity and feelings of being discriminated against to perceived quality of care. As shown in model 1, compared to non-Hispanic white respondents, Asian/PIs (adjusted PR = 1.31, 95% CI 1.23-1.38) and African Americans (adjusted PR = 1.15, 95% CI 1.05–1.26) were more likely to report lower ratings of care compared to non-Hispanic whites. Hispanic Americans, in contrast, were more likely to report higher ratings of care compared to non-Hispanic whites (adjusted PR = 0.92, 95% CI 0.87–0.98). As shown in model 2, respondents who reported experiencing discrimination had twice the prevalence rates of lower perceived quality of care compared to those who did not report experiencing discrimination in health care (adjusted PR = 2.11, 95% CI 1.98–2.23). Furthermore, feeling discriminated against fully accounted for the association between African-American race and lower ratings of perceived quality of care. In model 3, even when other sociodemographic factors, such as low education level, limited English language proficiency, and lacking health insurance, were added to the model, perceived discrimination remained an independent predictor of perceived quality of care (adjusted PR = 2.07, 95% CI 1.94–2.19). In the analysis stratified by race/ethnicity (see Table 3), feeling discriminated against in health care remained significantly associated with lower ratings of perceived quality of care across all groups (all p values < 0.05), even after adjusting for sociodemographic variables and other indicators of access and satisfaction.

DISCUSSION

This study is among the first to examine the association between perceived discrimination and perceived quality of care in a large, ethnically and racially diverse population-based sample and to evaluate the sociodemographic variables and other indicators of access and satisfaction associated with perceptions of health care quality within four primary racial/ethnic groups. In this representative cohort of California’s non-institutionalized adults, we found that Asians and African Americans were less likely than other racial/ethnic groups to rate the quality of their health care favorably. In addition, although discrimination in health care was reported by respondents from all racial/ethnic backgrounds, members of minority populations were significantly more likely to report being discriminated against compared to non-Hispanic whites. Across racial/ethnic groups, respondents who believed that they would have gotten better health care if they were of a different race were more likely to report lower quality of care.

Interestingly, we found that after adjusting for perceived discrimination, African-American race was no longer a significant predictor of ratings of quality care, suggesting that the difference between African Americans and non-Hispanic whites′ ratings of quality care can be explained primarily by African Americans perceptions of discrimination in the health care setting. This finding is consistent with other studies among African Americans where perceived racism had a significant effect on patients′ ratings of care.7,10 For example, La Viest and colleagues found that African American race was not an independent predictor of poor patient ratings of care after accounting for patients′ ratings of perceived discrimination in a sample of cardiac patients.28

Similar to findings from other studies, Asian Americans reported lower ratings of quality care compared to non-Hispanic whites.29,30 This difference persisted even after adjusting for ratings of perceived discrimination, suggesting that other factors may be more important in trying to understand Asian Americans′ low ratings of health care quality. The findings from this study highlight specific challenges associated with perceived health care quality that Asian Americans encounter, such as problems with access to specialists and problems finding a personal doctor with whom they are happy. While it may be the case that racial/ethnic differences in ratings of care reflect different response tendencies rather than actual differences in experiences with care,9,31,32 other conflicting evidence suggests that Asian Americans are truly more dissatisfied with their care than non-Hispanic whites.29,33,34 Some researchers have argued that one recommended strategy for trying to address response bias when comparing ratings across different cultural/ethnic populations is to collapse responses at the higher end of the scale.9 Nonetheless, understanding other factors associated with Asian Americans greater dissatisfaction with their health care quality is an important step for future research.

Hispanics in our study reported the highest quality of care ratings despite reporting high discrimination rates. In previous research based on the National Consumer Assessment of Health Plans Study (CAHPS) data,9 Hispanics reported negative experiences in every specific area assessed, including getting health care needed, provider communication, and timeliness of care, yet they rated the health care received more positively than any other racial or ethnic group.9 This was particularly true for Hispanics who spoke only or mostly Spanish, as we found in our study. For Hispanic respondents, ratings of discrimination, health care access, and satisfaction with the provider were significantly associated with ratings of perceived quality, suggesting that Hispanics are more satisfied with their health care when the entire system provides a setting that is culturally and linguistically compatible.35

Our study is subject to several limitations. The cross-sectional study design precludes causal inferences between racial/ethnic discrimination in health care and perceived quality of care. People who are more sensitive to discrimination or more apt to report it may also be more sensitive and willing to report other problems with their health care. Furthermore, the definition of quality of care may vary widely among patients, even within the same race or ethnicity. Due to the design of this study, we cannot determine if the differences in reported quality of care were due to patient expectations, differences in perception, or actual care received. Nevertheless, this study highlights the importance of understanding the relationship between perceived discrimination and ratings of quality care within each racial/ethnic group.

This research documents the existence of perceived racial and ethnic discrimination in health care and its association with respondents′ ratings of perceived quality of care. Although the overall prevalence of perceived discrimination in health care settings appears to be relatively low, the experience of such discrimination is strongly associated with respondents′ evaluations of their overall health care experience. The belief that the quality of care received is lower than that received by members of other racial/ethnic groups may be a contributing or mediating factor not only in health care satisfaction,14,16,17 but also in adherence to medical advice10 and medication regimens.10,12 Even when receiving medical care considered to be objectively adequate by other process or outcome measures, patients may rate it as poor if they felt discriminated against or mistreated in the process. Furthermore, perceived discrimination has profound health impacts.36,37 Previous studies have found that perceived racial/ethnic discrimination has been associated with worse mental and physical health among African Americans,38,39 Hispanics,40 and Asians.41 Therefore, efforts to improve quality of care in the US must also address racial/ethnic discrimination and perceptions of inequality in the health care system.42 Such efforts may be most effective if they target populations that are at greatest risk for perceiving discrimination and the underlying factors associated with ratings of poor health care quality.

References

Collins KS, Hughes D, Doty MM, Ives BL, Edwards JN, Tenney K. Diverse communities, common concerns: assessing health care quality for minority Americans. New York: The Commonwealth Fund; 2002.

Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2003.

van Ryn M. Research on the provider contribution to race/ethnicity disparities in medical care. Med Care 2002:1140-51.

van Ryn M, Burke J. The effect of patient race and socio-economic status on physicians′ perceptions of patients. Soc Sci Med. 2000;50(6):813–28.

Collins TC, Clark JA, Petersen LA, Kressin NR. Racial differences in how patients perceive physician communication regarding cardiac testing. Med Care. 2002;40(1 Suppl):I27–34.

Trivedi AN, Ayanian JZ. Perceived discrimination and use of preventive health services. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):553–8.

Benkert R, Peters RM, Clark R, Keves-Foster K. Effects of perceived racism, cultural mistrust and trust in providers on satisfaction with care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2006;98(9):1532–40.

Morales LS, Elliott MN, Weech-Maldonado R, Spritzer KL, Hays RD. Differences in CAHPS adult survey reports and ratings by race and ethnicity: an analysis of the National CAHPS benchmarking data 1.0. Health Serv Res. 2001;36(3):595–617.

Weech-Maldonado R, Morales LS, Elliott M, Spritzer K, Marshall G, Hays RD. Race/ethnicity, language, and patients′ assessments of care in Medicaid managed care. Health Serv Res. 2003;38(3):789–808.

Blanchard J, Lurie N. R-E-S-P-E-C-T: patient reports of disrespect in the health care setting and its impact on care. J Fam Pract. 2004;53(9):721–30.

Trivedi AN, Ayanian JZ. Perceived discrimination and use of preventive health services. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):553–8.

Van Houtven CH, Voils CI, Oddone EZ, Weinfurt KP, Friedman JY, Schulman KA, Bosworth HB. Perceived discrimination and reported delay of pharmacy prescriptions and medical tests. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(7):578–83.

Bird S, Bogart LM. Perceived race-based and socioeconomic status(SES)-based discrimination in interactions with health care providers. Ethn Dis. 2001;11(3):554–63.

Johnson RL, Saha S, Arbelaez JJ, Beach MC, Cooper LA. Racial and ethnic differences in patient perceptions of bias and cultural competence in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(2):101–10.

Lauderdale DS, Wen M, Jacobs EA, Kandula NR. Immigrant perceptions of discrimination in health care: the California Health Interview Survey 2003. Med Care. 2006;44(10):914–20.

Haviland MG, Morales LS, Reise SP, Hays RD. Do health care ratings differ by race or ethnicity? Jt Comm J Qual Saf. 2003;29(3):134–45.

Haviland MG, Morales LS, Dial TH, Pincus HA. Race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and satisfaction with health care. Am J Med Qual. 2005;20(4):195–203.

Chen FM, Fryer GE, Phillips RL, Wilson E, Pathman DE. Patients′ beliefs about racism, preferences for physician race, and satisfaction with care. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(2):138–43.

LaVeist T, Rolley NC, Diala C. Prevalence and patterns of discrimination among US health care consumers. Int J Health Serv. 2003;33(2):331–44.

Kandula NR, Hasnain-Wynia R, Thompson JA, Brown ER, Baker DW. Association between prior experiences of discrimination and patients′ attitudes towards health care providers collecting information about race and ethnicity. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(7):789–94.

Burgess DJ, Ding Y, Hargreaves MK, van Ryn M, Phelan S. The association between perceived discrimination and underutilization of needed medical and mental health care in a multi-ethnic community sample. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2008;19:894–911.

Perez D, Sribney WM, Rodriguez MA. Perceived discrimination and self-reported quality of care among Latinos in the United States. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(Suppl 3):548–54.

California Health Interview Survey. CHIS 2003 Methodology Series: Report 2-2003 Data Collection Methods. Available at http://www.chis.ucla.edu/pdf/CHIS2003_method2.pdf. Accessed on January 4, 2010.

California Health Interview Survey. CHIS 2003 Methodology Series: Report 4-2003 Response Rates. Available at http://www.chis.ucla.edu/pdf/CHIS2003_method4.pdf. Accessed on January 4, 2010. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA Center for Health Policy Research.

California Health Interview Survey. CHIS 2003 Methodology Series: Report 1-2003 Sample Design. Available at http://www.chis.ucla.edu/pdf/CHIS2003_method1.pdf. Accessed on January 4, 2010.

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–83.

Zhang J, Yu KF. What's the relative risk? A method of correcting the odds ratio in cohort studies of common outcomes. Jama. 1998;280(19):1690–1.

LaVeist TA, Nickerson KJ, Bowie JV. Attitudes about racism, medical mistrust, and satisfaction with care among African American and white cardiac patients. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(4_suppl):146–61.

Ngo-Metzger Q, Legedza ATR, Phillips RS. Asian Americans′ reports of their health care experiences: results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:111–9.

Sofaer S, Gruman J. Consumers of health information and health care: challenging assumptions and defining alternatives. Am J Health Promot. 2003;18(2):151–6.

Murray-Garcia JL, Selby JV, Schmittdiel J, Grumbach K, Quesenberry CP Jr. Racial and ethnic differences in a patient survey: patients′ values, ratings, and reports regarding physician primary care performance in a large health maintenance organization. Med Care. 2000;38(3):300–10.

Saha S, Hickam DH. Explaining low ratings of patient satisfaction among Asian-Americans. Am J Med Qual. 2003;18(6):256–64.

Ngo-Metzger Q, Sorkin DH, Phillips RS, Greenfield S, Massagli MP, Clarridge B, Kaplan SH, Feinstein AR. Providing high-quality care for limited English proficient patients: the importance of language concordance and interpreter use. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:324–30.

Teresi JA, Stewart AL, Morales LS, Stahl SM. Measurement in a multi-ethnic society. Overview to the special issue. Med Care. 2006;44(11 Suppl 3):S3–4.

Saha S, Komaromy M, Koepsell TD, Bindman AB. Patient-physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(9):997–1004.

Williams DR, Neighbors HW, Jackson JS. Racial/Ethnic discrimination and health: findings from community studies. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):200–8.

Krieger N. Chapter 3, discrimination and health. In: Berkman LF, Kawachi I, eds. Social epidemiology. New York: Oxford University Press; 2000:36–75.

Williams D, Neighbors H. Racism, discrimination and hypertension: evidence and needed research. Ethn Dis. 2001;11(4):800–16.

Wyatt SB, Williams DR, Calvin R, Henderson FC, Walker ER, Winters K. Racism and cardiovascular disease in African Americans. Am J Med Sci. 2003;325(6):315–31.

Finch BK, Kolody B, Vega WA. Perceived discrimination and depression among Mexican-origin adults in California. J Health Soc Behav. 2000;41(3):295–313.

Noh S, Kaspar V. Perceived discrimination and depression: moderating effects of coping, acculturation, and ethnic support. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(2):232–8.

De Alba I, Hubbell FA, McMullin JM, Sweningson JM, Saitz R. Impact of US citizenship status on cancer screening among immigrant women. The. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(3):290–6.

Acknowledgments

Financial Disclosure: The authors have no financial disclosures and no conflict of interests to disclose related to this manuscript. Dr. Sorkin received support from a NIH K01 award (NIDDK DK 078939). Dr. Ngo-Metzger received support from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Generalist Physician Faculty Scholar Award (Grant no. 1051084).

Author Contributions: Sorkin: study concept and design, data analysis, interpretation of data, and drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. Ngo-Metzger: study concept and design, interpretation of data, drafting and revision of manuscript. De Alba: study concept and design, interpretation of data, and drafting of manuscript.

Sponsor′s Role: No funding agencies were involved in the design, methods, subject recruitment, data collection, analysis, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Sorkin, D.H., Ngo-Metzger, Q. & De Alba, I. Racial/Ethnic Discrimination in Health Care: Impact on Perceived Quality of Care. J GEN INTERN MED 25, 390–396 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1257-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1257-5