Abstract

BACKGROUND

Despite both parties often expressing dissatisfaction with consultations, patients with medically unexplained symptoms (MUS) prefer to consult their general practitioners (GPs) rather than any other health professional. Training GPs to explain how symptoms can relate to psychosocial problems (reattribution) improves the quality of doctor–patient communication, though not necessarily patient health.

OBJECTIVE

To examine patient experiences of GPs’ attempts to reattribute MUS in order to identify potential barriers to primary care management of MUS and improvement in outcome.

DESIGN

Qualitative study.

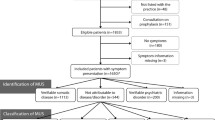

PARTICIPANTS

Patients consulting with MUS whose GPs had been trained in reattribution. A secondary sample of patients of control GPs was also interviewed to ascertain if barriers identified were specific to reattribution or common to consultations about MUS in general.

APPROACH

Thematic analysis of in-depth interviews.

RESULTS

Potential barriers include the complexity of patients’ problems and patients’ judgements about how to manage their presentation of this complexity. Many did not trust doctors with discussion of emotional aspects of their problems and chose not to present them. The same barriers were seen amongst patients whose GPs were not trained, suggesting the barriers are not particular to reattribution.

CONCLUSIONS

Improving GP explanation of unexplained symptoms is insufficient to reduce patients’ concerns. GPs need to (1) help patients to make sense of the complex nature of their presenting problems, (2) communicate that attention to psychosocial factors will not preclude vigilance to physical disease and (3) ensure a quality of doctor–patient relationship in which patients can perceive psychosocial enquiry as appropriate.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Salmon P, Peters S, Stanley I. Patients’ perceptions of medical explanations for somatisation disorders: qualitative analysis. BMJ. 1999;318:372–6.

Kirmayer LJ, Robbins JM. Patients who somatize in primary care: a longitudinal study of cognitive and social characteristics. Psychol Med. 1996;26:937–951.

Arnold IA, Speckens AE, van Hemert AM. Medically unexplained physical symptoms: the feasibility of group cognitive–behavioural therapy in primary care. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57:517–20.

Goldberg D, Gask L, O’Dowd T. The treatment of somatisation: teaching techniques of reattribution. J Psychosom Res. 1989;33:689–95.

Morriss R, Dowrick C, Salmon P, et al. Turning theory into practice: rationale, feasibility and external validity of an exploratory randomized controlled trial of training family practitioners in reattribution to manage patients with medically unexplained symptoms (MUST). Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2006;28:343–51.

Morriss R, Gask L, Dowrick C, Salmon P, Peters S. Primary care: management of persistent medically unexplained symptoms. In: Lloyd GG, Guthrie E, eds. Handbook of Liaison Psychiatry. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007.

Morriss RK, Gask L, Ronalds C, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a new treatment for somatized mental disorder taught to GPs. Fam Pract. 1998;15:119–25.

Morriss RK, Gask L, Ronalds C, Downes-Grainger E, Thompson H, Goldberg D. Clinical and patient satisfaction outcomes of a new treatment for somatized mental disorder taught to general practitioners. Br J Gen Pract. 1999;49:263–7.

Blankenstein AH. Somatising patients in general practice reattribution, a promising approach. PhD thesis. Netherlands: Vrije Universiteit; 2001.

Morriss RK, Gask L. Treatment of patients with somatized mental disorder: effects of reattribution training on outcomes under the direct control of the family doctor. Psychosomatics. 2002;43:394–9.

Larisch A, Schweickhardt A, Wirsching M, Fritzsche K. Psychosocial interventions for somatizing patients by the general practitioner: a randomized controlled trial. J Psychosom Res. 2004;57:507–14.

Frostholm L, Fink P, Oernboel E, et al. The uncertain consultation and patient satisfaction: the impact of patients’ illness perceptions and a randomized controlled trial on the training of physicians’ communication skills. Psychosom Med. 2005;67:897–905.

Rosendal M, Bro F, Sokolowski I, Fink P, Toft T, Olesen F. A randomised controlled trial of brief training in assessment and treatment of somatisation: effects on GPs’ attitudes. Fam Pract. 2005;22:419–27.

Aiarzaguena JM, Grandes G, Gaminde I, Salazar A, Sánchez A, Ariño J. A randomized controlled clinical trial of a psychosocial and communication intervention carried out by GPs for patients with medically unexplained symptoms. Psychol Med. 2007;37:283–94.

Morriss R, Dowrick C, Salmon P, et al. Exploratory randomised controlled trial of training practices and general practitioners in reattribution to manage patients with medically unexplained symptoms (MUST). Brit J Psychiatry. 2007;191:536–42.

Haynes B, Haines A. Getting research findings into practice: Barriers and bridges to evidence based clinical practice. BMJ. 1998;317:273–6.

Bradley F, Wiles R, Kinmonth A-L, Mant D, Gantley M. Development and evaluation of complex interventions in health services research: case study of the Southampton heart integrated care project (SHIP). BMJ. 1999;318:711–5.

Campbell M, Fitzpatrick R, Haines A, et al. Framework for design and evaluation of complex interventions to improve health. BMJ. 2000;321:694–6.

Medical Research Council. A frame work for development and evaluation of RCTs for complex interventions to improve health. London: MRC; 2000.

Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory. 2Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 1998.

Henwood KL, Pidgeon NF. Qualitative research and psychological theorizing. Br J Psychol. 1992;83:97–111.

Stiles WB. Quality-control in qualitative research. Clin Psychol Rev. 1993;13(6):593–618.

Cheraghi-Sohi S, Hole AR, Mead N, et al. What patients want from primary care consultations: A discrete choice experiment to identify patients’ priorities. Annals of Family Medicine. 2008;6(2):107–15.

Hartz AJ, Noyes R, Bentler SE, Damiano PC, Willard JC, Momany ET. Unexplained symptoms in primary care: Perspectives of doctors and patients. Gen Hosp Psych. 2000;22(3):144–52.

Barry CA, Bradley CP, Britten N, Stevenson FA, Barber N. Patients’ unvoiced agendas in general practice consultations: qualitative study. BMJ. 2000;320:1246–50.

Nordin T, Hartz AJ, Noyes R, et al. Empirically identified goals for the management of unexplained symptoms. Fam Med. 2006;38(7):476–82.

Thom DH, Campbell B. Patient–physician trust: an exploratory study. J Family Pract. 1997;44(2):169–76.

Chew-Graham C, Cahill G, Dowrick C, Wearden A, Peters S. Using multiple sources of knowledge to reach clinical understanding of chronic fatigue syndrome. Annals of Family Medicine. 2008;6:340–8.

Werner A, Malterud K. It is hard work behaving as a credible patient: encounters between women with chronic pain and their doctors. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(8):1409–19.

Dirkzwager AJE, Verhaak PFM. Patients with persistent medically unexplained symptoms in general practice: characteristics and quality of care. BMC Fam Pract. 2007;33(8).

Buszewicz M, Pistrang N, Barker C, Cape J, Martin J. Patients’ experiences of GP consultations for psychological problems: a qualitative study. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56:496–503.

Salmon P, Ring A, Dowrick CF, et al. What do general practice patients want when they present medically unexplained symptoms, and why do their doctors feel pressurised? J Psychosom Res. 2005;59:255–60.

Salmon P, Humphris GM, Ring A, Davies JC, Dowrick CF. Primary care consultations about medically unexplained symptoms: patient presentations and doctor responses that influence the probability of somatic intervention. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:571–7.

Berry LL, Parish JT, Janakiraman R, et al. Patients’ commitment to their primary physician and why it matters. Annals of Family Medicine. 2008;6(1):6–13.

Epstein RM, Hadee T, Carroll J, Meldrum SC, Lardner LJ, Shields CG. “Could this be something serious?” — reassurance, uncertainty and empathy in response to patients’ expressions of worry. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(12):1731–9.

McKinstry B, Ashcroft AE, Car J, Freeman GK, Sheikh A. Interventions for improving patients’ trust in doctors and groups of doctors. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD004134.

Blakeman T, Macdonald W, Bower P, Gately C, Chew-Graham C. A qualitative study of GPs’ attitudes to self-management of chronic disease. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56:407–14.

Kroenke K, Spitzer R. Gender differences in the reporting of physical and somatoform symptoms. Psychosom Med. 1998;60(2):150–5.

Salmon P, Peters S, Clifford R, Iredale W, Gask L, Rogers A, Dowrick C, Morriss R. Why do general practitioners decline training to improve management of medically unexplained symptoms? J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:565–71.

Acknowledgments

Funding for the project came from the UK Medical Research Council (grant reference no. G0100809, ISRCTN 44384258), Mersey Care NHS Trust and Mersey Primary Care Research Organisation. We are grateful for the cooperation of the participating patients and physicians and collaboration of Professor Francis Creed, Professor Graham Dunn, Dr Huw Charles Jones and Dr Barry Lewis in the design of the MUST trial, and to Judith Hogg for managing the trial.

Conflict of interest

None disclosed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Peters, S., Rogers, A., Salmon, P. et al. What Do Patients Choose to Tell Their Doctors? Qualitative Analysis of Potential Barriers to Reattributing Medically Unexplained Symptoms. J GEN INTERN MED 24, 443–449 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0872-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-008-0872-x