Abstract

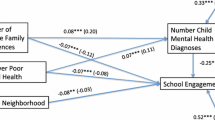

Given prevalence rates and negative consequences that adolescents’ perpetration of dating violence may have on an individual’s well-being and future relationships, it is imperative to explore factors that may increase or reduce its occurrence. Thus, we aimed to identify how multiple contextual risk factors (individual, family, schools, and neighborhoods) were related to adolescents’ perpetration of dating violence over a 6 year period. Then, we assessed how neighborhood collective efficacy, an important predictor of urban youths’ well-being, buffered the relationship between each of the risk factors and adolescents’ perpetration of dating violence. Three waves of data from the Welfare, Children, and Families: A Three-City Study were used (N = 765; Ages 16–20 at Wave 3). The sample is 53 % female, 42 % African-American, and 53 % Hispanic. For the total sample, drug and alcohol use, low parental monitoring, academic difficulties, and involvement with antisocial peers were significant early risk factors for perpetration of dating violence in late adolescence. Risk factors also varied by adolescents’ race and sex. Finally, perceived neighborhood collective efficacy buffered the relationship between early academic difficulties and later perpetration of dating violence for Hispanic males. These results imply that multiple systems should be addressed in dating violence prevention programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Models were first examined with family income, family structure, time in neighborhood, and number of moves, as well as adolescents’ race and sex and mother’s education. For parsimony, final models are presented and discussed with only adolescents’ race and sex and mother’s education because family income (M = $1088.01 per month, SD = $809.30), family structure (81.3% single parent), time in neighborhood (M = 113.11 months, SD = 129.37), and number of moves (M = 1.23, SD = 1.03) were not significant and results did not change with their exclusion.

Hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) was first utilized in the present study to account for the nested nature of the data and to test the two hypotheses. In this analysis, Census tracts (N = 216) were combined based on geography in over 93% of cases to ensure that at least 80% of the neighborhood clusters had more than 10 adolescents (Maas and Hox 2005). Weighted averages of the Census variables were then calculated and utilized in an HLM analysis. HLM models revealed no significant slope or intercept variation across neighborhood clusters, which warranted the use of lagged OLS regression models instead.

References

Achenbach, T. M. (1991). Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile. Burlington: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry.

Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage.

Aisenberg, E., & Ell, K. (2005). Contextualizing community violence and its effects: An ecological model of parent-child interdependent coping. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20, 855–871.

Allen, J. P., Hauser, S. T., Eickholt, C., Bell, K. L., & O’Connor, T. G. (1994). Autonomy and relatedness in family interactions as predictors of expressions of negative adolescent affect. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 4(4), 535–552.

Almgren, G. (2005). The ecological context of interpersonal violence: From culture to collective efficacy. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 20, 218–224.

Armsden, G. C., & Greenberg, M. T. (1987). The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 16, 427–454.

Bandura, A. (1977). Social Learning Theory. New York: General Learning Press.

Bean, R. A., Perry, B. J., & Bedell, T. M. (2001). Developing culturally competent marriage and family therapists: Guidelines for working with Hispanic families. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 27, 43–54.

Borus, M. E., Carpenter, S. W., Crowley, J. E., Daymont, T. N., et al. (1982). Pathways to the future, Volume II: A final report on the National Survey of Youth labor market experience in 1980. Columbus: Center for Human Resource Research, The Ohio State University.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1989). Ecological systems theory. Annuals of Child Development, 6, 187–249.

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1993). The ecology of cognitive development: Research models and fugitive findings. In R. H. Wozniak & K. W. Fischer (Eds.), Development in context: Acting and thinking in specific environments. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

Brooks-Gunn, J., Duncan, G. J., Leventhal, T., & Aber, J. L. (1997). Lessons learned and future directions for research. In J. Brooks-Gunn, G. J. Duncan, & J. L. Aber (Eds.), Neighborhood poverty: Context and consequences for children (Vol. 1, pp. 279–297). New York: Russell Sage.

Browning, C. R. (2002). The span of collective efficacy: Extending social disorganization theory to partner violence. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 64(4), 833–850.

Burton, L. M., & Jarrett, R. L. (2000). In the mix, yet on the margins: The place of families in urban neighborhood and child development research. Journal of Marriage & the Family, 62, 1114–1135.

Capaldi, D. M., Dishion, T. J., Stoolmiller, M., & Yoerger, K. (2001). Aggression toward female partners by at-risk young men: The contribution of male adolescent friendships. Developmental Psychology, 37(1), 61–73.

Capaldi, D. M., Pears, K. C., Patterson, G. R., & Owen, L. D. (2003). Continuity of parenting practices across generations in an at-risk sample: A prospective comparison of direct and mediated association. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 31(2), 127–142.

Carlson, B. E. (2000). Children exposed to intimate partner violence: Research findings and implications for intervention. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 1, 321–342.

U. S. Census Bureau (1997). Glossary of decennial census terms and acronyms. Retrieved on May 18, 2011 from http://www.census.gov/dmd/www/glossary.html#C.

Centers for Disease Control (2010). Understanding Teen Dating Violence Fact Sheet. Retrieved on May 18, 2011 from: http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/pdf/TeenDatingViolence_2010-a.pdf.

Chassin, L., Hussong, A., Barrera, M., Molina, B., Trim, R., & Ritter, J. (2004). Adolescent substance abuse. In R. M. Lerner & L. Steinberg (Eds.), Handbook of adolescent psychology (2nd ed., pp. 665–696). New Jersey: Wiley & Sons.

Cleveland, H. H., Herrera, V. M., & Stuewig, J. (2003). Abusive males and abused females in adolescent relationships: Risk factors similarity and dissimilarity and the role of relationship seriousness. Journal of Family Violence, 18(6), 325–339.

Coley, R. (2003). Daughter-father relationships and adolescent psychosocial functioning in low-income African-American families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 867–875.

Deng, S., Lopez, V., Roosa, M., Ryu, E., Burrell, L., Tein, J., et al. (2006). Family processes mediating the relationship of neighborhood disadvantage to early adolescent internalizing problems. Journal of Early Adolescence, 26, 206–231.

Derogatis, L. R. (2000). Brief Symptom Inventory 18, administration, scoring, and procedures manual. Minneapolis: National Computer Systems.

Ellickson, P. L., & McGuigan, K. A. (2000). Early predictors of adolescent violence. American Journal of Public Health, 90(4), 566–572.

Elliot, D. S., Wilson, W. J., Huizinga, D., Sampson, R. J., Elliott, A., & Rankin, B. (1996). The effects of neighborhood disadvantage on adolescent development. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency, 33, 389–426.

Farrington, D. P. (2005). Childhood origins of antisocial behavior. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 12, 177–190.

Feiring, C., Deblinger, E., Hoch-Espada, A., & Haworth, T. (2002). Romantic relationship aggression and attitudes in high school students: The role of gender, grade, and attachment and emotional styles. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 31, 373–385.

Foo, L., & Margolin, G. (1995). A multivariate investigation of dating aggression. Journal of Family Violence, 10(4), 351–377.

Foshee, V. A., Linder, F., MacDougall, J. E., & Bangdiwala, S. (2001). Gender differences in the longitudinal predictors of adolescent dating violence. Preventive Medicine, 32, 128–141.

Foshee, V. A., Ennett, S. T., Bauman, K. E., Benefield, T., & Suchindran, C. (2005). The association between family violence & adolescent dating violence onset: Does it vary by race, socioeconomic status, & family structure? Journal of Early Adolescence, 25, 317–344.

Franzini, L., Caughy, M., Spears, W., Eugenia, M., & Esquer, F. (2005). Neighborhood economic conditions, social processes, and self-rated health in low-income neighborhoods in Texas: A multilevel latent variable model. Social Science and Medicine, 61, 1135–1150.

Gifford-Smith, M., Dodge, K. A., Dishion, T. J., & McCord, J. (2005). Peer influence in children and adolescents: Crossing the bridge from developmental to intervention science. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 33(3), 255–265.

Gold, M. (1970). Delinquent behavior in an American city. Belmont: Brooks/Cole.

Gorman-Smith, D., & Tolan, P. (1998). The role of exposure to community violence & developmental problems among inner-city youth. Development and Psychopathology, 10, 101–116.

Gorman-Smith, D., Tolan, P. H., & Henry, D. B. (2000). A developmental-ecological model of the relation of family functioning to patterns of delinquency. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 16, 169–198.

Gutman, L. M., & Eccles, J. S. (2007). Stage-environment fit during adolescence: Trajectories of family relations and adolescent outcomes. Developmental Psychology, 43, 522–537.

Herrenkohl, T. I., Maguin, E., Hill, K. G., Hawkins, J. D., Abbott, R. D., & Catalano, R. F. (2000). Developmental risk factors for youth violence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 26, 176–186.

Herrenkohl, T. I., Sousa, C., Tajima, E. A., Herrenkohl, R. C., & Moylan, C. (2008). Intersection of child abuse and children’s exposure to domestic violence. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 9, 84–99.

Hilton, N. Z., & Harris, G. T. (2005). Predicting wife assault: A critical review and implications for policy and practice. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 6(1), 3–23.

Holmbeck, G. N. (2002). Post-hoc probing of significant moderational and meditational effects in studies of pediatric populations. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, Special Issue on Methodology and Design, 27, 87–96.

Horowitz, J. L., & Manski, C. F. (1998). Censoring of outcomes and regressors due to survey nonresponse: Identification and estimation using weights and imputations. Journal of Econometrics, 84, 37–58.

Howard, D., Qiu, Y., & Boekeloo, B. (2003). Personal and social contextual correlates of adolescent dating violence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 33, 9–17.

Jordan, K. (2002). School violence among culturally diverse populations. In L. A. Rapp-Paglicci, A. R. Roberts, & J. S. Wodarski (Eds.), Handbook of violence (pp. 326–346). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

Kaura, S. A., & Allen, C. M. (2004). Dissatisfaction with relationship power and dating violence perpetration by men and women. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 19(5), 576–588.

Keyes, C. L. M. (2004). Risk and resilience in human development: An introduction. Research in Human Development, 1(4), 223–227.

LaVoie, G., Robitaille, L., & Hebert, M. (2000). Teen dating relationships and aggression: An exploratory study. Violence Against Women, 6(1), 6–36.

LaVoie, F., Hebert, M., Tremblay, R., Vitaro, F., Vezina, L., & McDuff, P. (2002). History of family dysfunction and perpetration of dating violence by adolescent boys: A longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescent Health, 30, 375–383.

Lichter, E. L., & McCloskey, L. A. (2004). The effects of childhood exposure to marital violence on adolescent gender-role beliefs & dating violence. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 28, 344–357.

Maas, C. J. M., & Hox, J. J. (2005). Sufficient sample sizes for multilevel modeling. Methodology, 1, 86–92.

Margolin, G., & Gordis, E. B. (2000). The effects of family and community violence on children. Annual Review of Psychology, 51, 445–479.

Markowitz, F. E. (2001). Attitudes and family violence: Linking intergenerational and cultural theories. Journal of Family Violence, 16(2), 205–218.

Mazefsky, C. A., & Farrell, A. D. (2005). The role of witnessing violence, peer provocation, family support, and parenting practices in the aggressive behavior of rural adolescents. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 14(1), 71–85.

McCloskey, L. A., & Lichter, E. L. (2003). The contribution of marital violence to adolescent aggression across different relationships. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18, 390–412.

Moore, M. R., & Chase-Lansdale, L. P. (2001). Sexual intercourse and pregnancy among African-American girls in high-poverty neighborhoods: The role of family and perceived community environment. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 1146–1157.

Nix, R. L., Pinderhughes, E. E., Dodge, K. A., Bates, J. E., Pettit, G. S., & McFadyen-Ketchum, S. A. (1999). The relation between mothers’ hostile attribution tendencies and children’s externalizing behavior problems: The mediating role of mothers’ harsh discipline practices. Child Development, 70(4), 896–909.

O’Donnell, L., Stueve, A., Myint-U, A., Duran, R., Agronick, G., & Wilson-Simmons, R. (2006). Middle school aggression and subsequent intimate partner physical violence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 35, 693–703.

O’Keefe, M. (1994). Linking marital violence, mother-child/father-child aggression, and child behavior problems. Journal of Family Violence, 9(1), 63–78.

Ohmer, M., & Beck, E. (2006). Citizen participation in neighborhood organizations in poor communities and its relationship to neighborhood and organizational collective efficacy. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 33(1), 179–202.

Pettit, B., & McLanahan, S. (2003). Residential mobility and children’s social capital: Evidence from an experiment. Social Science Quarterly, 84, 632–649.

Rankin, B. H., & Quane, J. M. (2002). Social contexts and urban adolescent outcomes: The interrelated effects of neighborhoods, families, and peers on African-American youth. Social Problems, 49(1), 79–100.

Rosenbaum, A., & Leisring, P. A. (2003). Beyond power and control: Towards an understanding of partner abusive men. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 34(1), 7–22.

Royston, P. (2004). Multiple imputation of missing values. The Stata Journal, 4, 227–241.

Royston, P. (2005). Multiple imputation of missing values: Update. The Stata Journal, 2, 1–14.

Sampson, R. J., Raudenbush, S., & Earls, F. (1997). Neighborhoods and violent crime: A multilevel study of collective efficacy. Science, 277(5328), 918–924.

Sampson, R. J., Morenoff, J. D., & Earls, F. (1999). Beyond social capital: Spatial dynamics of collective efficacy for children. American Sociological Review, 64(5), 633–660.

Sampson, R. J., Morenoff, J. D., & Gannon-Rowley, T. (2002). Assessing “neighborhood effects”: Social processes and new directions in research. Annual Review of Sociology, 28, 443–478.

Schnurr, M. P., & Lohman, B. J. (2008). How much does school matter? An examination of adolescent dating violence perpetration. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37, 266–283.

Schwartz, M., O’Leary, S. G., & Kendziora, K. T. (1997). Dating aggression among high school students. Violence and Victims, 12(4), 295–305.

Shaw, C. R., & McKay, H. D. (1942). Juvenile delinquency and urban areas. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Shek, D. T. L. (2005). Paternal and maternal influences on the psychological well-being, substance abuse, and delinquency of Chinese adolescents experiencing economic disadvantage. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(3), 219–234.

Shek, D. T. L., & Ma, H. K. (2001). Parent-adolescent conflict and adolescent antisocial and prosocial behavior: A longitudinal study in a Chine context. Adolescence, 36(143), 545–555.

Steinberg, L., Mounts, N. S., Lamborn, S. D., & Dornbusch, S. M. (1991). Authoritative parenting and adolescent adjustment across varied ecological niches. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 1, 19–36.

Straus, M. A., Hamby, S., Boney-McCoy, S., & Sugarman, D. (1996). The revised conflict tactics scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues, 17, 283–316.

Thomas, S. P., & Smith, H. (2004). School connectedness, anger behaviors, and relationships of violent and nonviolent American youth. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 40(4), 135–148.

Tolan, P. H., Gorman-Smith, D., & Henry, D. B. (2002). Linking family violence to delinquency across generations. Social Policy, Research, and Practice, 5(4), 273–284.

Turner, C. F., Forsyth, B. H., O’Reilly, J. M., Cooley, P. C., Smith, T. K., Rogers, S. M., et al. (1998). Automated self-interviewing and the survey measurement of sensitive behaviors. In M. P. Couper, R. P. Baker, J. Bethlehem, C. Z. F. Clark, J. Martin, W. L. Nicholls II, & J. M. O’Reilly (Eds.), Computer assisted survey information collection (pp. 455–473). New York: Wiley.

Vazsonyi, A. T. (2003). Parent-adolescent relations and problem behaviors: Hungary, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and the United States. Marriage and Family Review. Special Issue: Parenting Styles in Diverse Perspectives, 35(3–4), 161–187.

Weden, M. M., Carpiano, R. M., & Robert, S. A. (2008). Subjective and objective neighborhood characteristics and adult health. Social Science and Medicine, 66, 1256–1270.

Wen, M., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2006). Objective and perceived neighborhood environment, individual SES and psychosocial factors, and self-rated health: An analysis of older adults in Cook County, Illinois. Social Science and Medicine, 63, 2575–2590.

Whitfield, C. L., Anda, R. G., Dube, S. R., & Felitti, V. J. (2003). Violent childhood experiences and the risk of intimate partner violence in adults: Assessment in a large health maintenance organization. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 18(2), 166–185.

Wickrama, K. A. S., & Bryant, C. M. (2003). Community context of social resources and adolescent mental health. Journal of Marriage and Family, 65, 850–866.

Williams, J. H., Van Dorn, R. A., Hawkins, J. D., Abbott, R., & Catalano, R. F. (2001). Correlates contributing to involvement in violent behaviors among young adults. Violence and Victims, 16, 371–388.

Williams, S. T., Conger, K. J., & Blozis, S. A. (2007). The development of interpersonal aggression during adolescence: The importance of parents, siblings, and family economics. Child Development, 78, 1526–1542.

Wilson, W. J. (1987). The truly disadvantaged: The inner-city, the underclass and public policy. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Winston, P., Angel, R., Burton, L., Chase-Lansdale, P., Cherlin, A., Moffitt, R., & Wilson, W. (1999). Welfare, Children, and Families: A Three-City Study, Overview and Design Report. Available at http://web.jhu.edu/threecitystudy/images/overviewanddesign.pdf.

Wolf, K. A., & Foshee, V. A. (2003). Family violence, anger expression styles, and adolescent dating violence. Journal of Family Violence, 18(6), 309–316.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the support of the following organizations. Government agencies: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (RO1 HD36093 “Welfare Reform and the Well-Being of Children”), Office of the Assistant Secretary of Planning and Evaluation, Administration on Developmental Disabilities, Administration for Children and Families, Social Security Administration, and National Institute of Mental Health. Foundations: The Boston Foundation, The Annie E. Casey Foundation, The Edna McConnell Clark Foundation, The Lloyd A. Fry Foundation, The Hogg Foundation for Mental Health, The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, The Joyce Foundation, The Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation, The W.K. Kellogg Foundation, The Kronkosky Charitable Foundation, The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, The Charles Stewart Mott Foundation, The David and Lucile Packard Foundation, The Searle Fund for Policy Research, and The Woods Fund of Chicago. A special thank you is extended to our research firm, Research Triangle Institute (RTI), as well as to the children and caregivers who graciously participated in the Three-City Study and gave us access to their lives.

Authors’ Contributions

This article was one chapter of Melissa Schnurr’s dissertation completed at Iowa State University. She conceived the study, was responsible for the statistical analyses and drafted the manuscript for her dissertation. As an Associate Investigator of the Three-City Study, Brenda Lohman was critical in designing and assessing adolescent dating violence in the third wave of data collection. As Melissa Schnurr’s doctoral adviser, Lohman participated in the design, coordination, and writing of all phases of this study.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schnurr, M.P., Lohman, B.J. The Impact of Collective Efficacy on Risks for Adolescents’ Perpetration of Dating Violence. J Youth Adolescence 42, 518–535 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-9909-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-013-9909-5