Abstract

Postlactational involution is the process following weaning during which the mammary gland undergoes massive cell death and tissue remodeling as it returns to the pre-pregnant state. Lobular involution is the process by which the breast epithelial tissue is gradually lost with aging of the mammary gland. While postlactational involution and lobular involution are distinct processes, recent studies have indicated that both are related to breast cancer development. Experiments using a variety of rodent models, as well as observations in human populations, suggest that deregulation of postlactational involution may act to facilitate tumor formation. By contrast, new human studies show that completion of lobular involution protects against subsequent breast cancer incidence.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cancer can be viewed as a disease of defective development, wherein the signaling processes that guide normal tissue growth and morphogenesis become deregulated to facilitate cancer cell proliferation and tissue invasion. For breast cancer specifically, a large body of research has focused on the role of developmental signaling pathways in tumor progression; progress in this area has been facilitated in part because unlike most organs, the majority of mammary development occurs postnatally. At birth, the mammary gland is present as a primitive anlage; during puberty, the epithelium branches and grows to fill the gland. Importantly, many of the cellular processes that control branching morphogenesis during normal breast development are found to participate in tumor growth and invasion as well [1].

Breast development does not stop with puberty; the mature mammary gland also undergoes dramatic changes with each cycle of pregnancy/lactation/postlactational involution (Fig. 1). During early pregnancy, the epithelium proliferates extensively to form tissue structures for producing milk, and then during late pregnancy and lactation the epithelial cells differentiate further to become specialized for high levels of milk component production. After lactation is complete, weaning of the infant induces postlactational involution, a process in which the majority of epithelial cells rapidly undergo programmed cell death and the remaining cells are remodeled into a glandular structure that resembles the prepregnant state. As postlactational involution represents an important mechanism for removing unnecessary epithelial cells in a regulated fashion, in many ways this process appears diametrically opposed to the uncontrolled epithelial proliferation evident in cancer. Accordingly, there has been much interest in defining how the signaling processes present in postlactational involution become deregulated in cancer, where intrinsic cell apoptosis mechanisms become suppressed. Investigations using animal models have revealed many of the specific mediators of involution-associated apoptosis, remodeling, and inflammation, and also how selective modulation of these mediators affect both the process of postlactational involution and propensity for cancer development [2].

Mouse mammary gland morphogenesis. Whole mounts (top row) and hematoxylin and eosin (H&E, bottom row) images of fourth inguinal mammary glands. 12-week old mice have developed a ductal tree that fills the fat pad. Lactating mice show extensive glandular growth and cellular differentiation, and this phenotype is rapidly lost during postlactational involution. Aging mice show gradual degeneration of the mammary gland so that by 18 months, only a spindly ductal structure remains. Scale bar for whole mount, 1 cm; for H&E, 50 μm

With organismal aging, there is a loss of breast epithelial tissue which is distinct from postlactational involution, in which the mammary gland gradually loses complexity and function. In humans, this phenomenon has been defined as age-related lobular involution. Lobular involution begins in perimenopause and accelerates during menopause, and is characterized as a decrease in the size and complexity of the ductal tree and of the terminal ductal lobular units (TDLU) [3]. While much remains to be learned about how lobular involution is regulated, recent clinical studies have shown that the process of lobular involution has considerable significance for development of breast cancer, as premenopausal women who were found to have undergone partial or complete lobular involution were also found to have substantially decreased risk of breast cancer, while postmenopausal women who showed delayed lobular involution were found to have a correspondingly elevated breast cancer risk [4]. These findings suggest that reduction of epithelial tissue associated with lobular involution may be a physiologically protective mechanism against breast cancer. In this review, we will briefly describe the processes of postlactational involution and lobular involution, and highlight investigations of these processes that have provided insight into mechanisms of cancer development and suggested new approaches for prevention or treatment of breast cancer.

Postlactational Involution and Breast Cancer

Mice provide a useful, tractable model for studying postlactational involution, as normalization of the number of suckling pups standardizes mammary differentiation during lactation, and simultaneous removal of suckling pups induces postlactational involution in a synchronous fashion. Studies employing mouse models have shown that postlactational involution proceeds through an initial, reversible stage in which there is widespread apoptotic cell death, followed by an irreversible second stage in which the mammary gland is remodeled to the pre-pregnant state [5]. The first stage is triggered by cessation of suckling, whereupon continued milk production causes distension of the alveolar lumen. Nipple sealing experiments have shown that this milk stasis is sufficient to induce the first stage of postlactational involution, in which epithelial cells are shed into the acinar lumen [6, 7]. These shed cells express markers of apoptosis, including redistribution of phosphatidylserine to the outer leaflet of the cell membrane and cleavage of the key apoptosis mediator caspase 3 [8], although it is not clear whether apoptosis in these cells is a cause or consequence of detachment from the basement membrane [5].

The second, irreversible stage of postlactational involution begins at approximately 48 h after weaning. A gradual reduction of circulating hormones during the first stage is necessary for progression to this stage [7, 9]. Here, there is glandular collapse, redifferentiation of adipocytes, and remodeling of the ductal epithelium. Breakdown of the basement membrane, a specialized extracellular matrix that surrounds the mammary epithelium, is a key step in tissue remodeling, and there is substantial expression of serine and matrix metalloproteinases during the second stage of involution [10]. Associated with loss of the basement membrane, caspase 3-staining can be seen in the acinar cell wall by 72 h.

While postlactational involution is normally a highly controlled process, the rapid and extensive tissue breakdown and remodeling is not without risk. The highly reactive nature of the remodeling gland is reminiscent of pathological conditions such as wound healing and tumor development. The proteinase expression profiles in the remodeling gland are similar to that found in developing breast tumors [11], and transcriptional profiling studies have provided evidence of the activation of many inflammatory processes, including both innate and adaptive immune responses [12–14]. These studies found an increase in proinflammatory cytokines and neutrophil chemoattractants during the first stage of involution, followed by a more sustained elevation of chemoattractants for and markers of monocytes and macrophages during the second stage. There were also a substantial number of transcripts for immunoglobulins, indicating the presence of activated B-cells. Analysis of the transcriptional profiles of postlactatational glands revealed a high level of similarity to those found in wound healing and the tumor microenvironment, including expression of many growth factors, cytokines, and tissue morphogens [15, 16].

Although postlactational involution normally proceeds without pathological consequences, the deregulation of tissue structure and activation of tumor microenvironment characteristics may act to facilitate the outgrowth of premalignant cells present in the mammary gland [17]. This possibility has been validated by experiments which isolated extracellular matrix (ECM) from nulliparous or postlactational mammary glands, and found that ECM from the remodeling glands contained tumorigenic ECM fragments that could facilitate outgrowth of breast cancer cells in culture, as well as promote increased breast cancer metastasis in animal models [18–20]. Intriguingly, the tumor-promoting potential of the involuting mammary gland has been suggested to underlie the elevated incidence of breast cancer associated with pregnancy [17].

Transgenic Models of Postlactational Involution

A number of gene promoters are active in mammary epithelial cells, and some are specifically activated during pregnancy. Transgenic mouse models that use these promoters to selectively activate or remove a particular gene from mammary epithelial cells have greatly facilitated the dissection of mammary gland developmental processes. To date, more than 50 transgenic mouse models have been reported to show alterations in postlactational involution (Table 1). In many cases, the effect on involution is consistent with previously identified expression patterns in the involuting gland. Postlactational involution is inhibited by the deletion of cytokines normally upregulated in the involuting gland, such as FasL [21], IL-6 [22], IL-10 [23], and LIF [24], and is accelerated by their premature expression, as for TGF-β3 [25]. Similarly, manipulation of cell death pathways also alters the timing of postlactational involution: deletion of the apoptosis inducer Bax delays involution, while decreased expression of the apoptosis inhibitor Bcl2 accelerates involution [26, 27]. The secreted protein milk fat globule-EGF-factor 8 (Mfge8) binds to apoptotic cells through recognition of phosphatidyl serine in the outer leaflet and has been implicated in phagocytosis; mice lacking Mfge8 have decreased clearance of apoptotic cells and delays in the second stage of postlactational involution [28, 29].

Transgenic models also have provided insight into the complexity of the processes that govern postlactational involution. Mammary gland remodeling is associated with increased expression of a number of proteases, including matrix metalloproteinase-3 (MMP-3) and plasminogen (Plg) [30, 31]. Accordingly, induced expression of MMP-3 causes premature involution while deletion of Plg causes delays in glandular remodeling [32–35]. However, further examination reveals that these proteases affect mammary gland development though multiple mechanisms. Mice lacking MMP-3 do not show a significant delay in involution but rather altered differentiation of adipocytes [33], potentially implicating overlapping functions of different MMPs; mice lacking Plg show evidence of premature activation of the first stage of postlactational involution, possibly through increased milk production in these mice [36].

Many of these transgenic mouse models revealed unexpected connections between the processes of postlactational involution and mammary tumor growth and progression. In some cases, mouse models which were created to investigate the effects of increased expression of breast oncogenes (ErbB2/neu [37, 38] and Akt1 [39–42]) were found subsequently to have delays in postlactational involution. Similarly, many of the transgenic mice that show alterations in postlactatational involution also show increased tumor development or progression. In some of these cases, the connection between the two phenomena is straightforward: suppression of cell death delays involution and facilitates tumor progression in mice lacking Bax [27, 43] or expressing Bcl-2 [26, 27, 44] or Akt1 [39, 41, 42].

For many transgenic mice showing both delayed postlactational involution and increased tumor production, the relationship between the two functions is not clear. In some cases, there may be unexpected, yet-to-be-identified tumor signaling pathways. However, another possibility is that delayed involution enhances the intrinsic tumor promoting capability of the postlactational mammary gland, identified in cell culture and animal studies and implied by the increased incidence of pregnancy-associated breast cancer in humans [17]. Moreover, as disruption of tissue structure can activate genomic instability [45], prolonged postlactational involution could potentially foster both cancer initiation and progression.

Examples that appear at variance with the correlation between delayed postlactational involution and increased tumorigenesis include mice overexpressing Cripto [46, 47], MMP3 [32, 33, 35, 48, 49] or myc [26, 50], which show premature involution but increased incidence of cancer. In some cases, the transgene may impair mammary development during pregnancy, which could complicate comparisons of involution rates, as has been suggested for mice overexpressing Cripto [46, 47]. While the reason for premature involution in MMP3-and myc-overexpressing mice remains unclear, these models may reflect activation of common signaling pathways, as exposure of mammary epithelial cells to MMP3 was previously found to increase expression of myc [51]. We point out that for many of the transgenic mice with defects in postlactational involution, the effect on tumor progression remains unknown; similarly, many mammary tumor models have never been investigated for rate of postlactational involution, and this represents a critical area for future research. More complete characterization of the involution phenotype for mammary tumor-associated transgenic mouse models may eventually assist in unraveling the complex relationships between involution pathways and cancer.

Lobular Involution and Breast Cancer

Lobular involution is a distinct process from postlactational involution. Unlike the dramatic cell death and morphogenesis following weaning, lobular involution is associated with a gradual decrease in the complexity and extent of ductal epithelium with age (Fig. 2). While aging mice show an epithelial degeneration process that is reminiscent of lobular involution (Fig. 1), most research about lobular involution has focused on human studies. While there are substantial similarities between human and mouse mammary glands, there are important differences as well. The human breast is organized into 15–20 major lobes, each made up of lobules that contain the milk-forming acini; the acini are grouped at the ends of the ducts to form structures known as terminal duct lobular units (TDLUs; see inset, Fig. 3a). During pregnancy and lactation, the TDLUs develop into secretory, milk-producing, lobular alveoli, and the surrounding fat cells diminish [52]; during postlactational involution, the TDLUs return to the prepregnant state without a cumulative loss of glandular tissue [53, 54]. By contrast, age-related lobular involution appears to be an irreversible process, in which the number and size of acini per lobule are reduced and the delicate intralobular stroma is replaced with collagen from connective tissue (Fig. 3b) [3]. Ultimately the glandular epithelium and stroma regress and are replaced by fat [55]. The tempo and extent of lobular involution vary considerably among individual women [3]; in an autopsy series, evidence that lobular involution had begun was found in up to 33% of women younger than 40 years of age [56].

Breast whole mounts of preinvolutional (a) and postinvolutional (b) women. Reprinted with permission of Springer Science+Business Media. Originally published in “Handbuch der mikroskopischen Anatomie des Menschen.” (W. Bargmann, ed.), Vol 3, part 3, Haut und Sinnesorgane, pp. 277–485, 1957. Springer-Verlag, Berlin)

Histologic features of age-related lobular involution. a Noninvoluted breast tissue shows multiple, large terminal duct lobular units (TDLU) which contain numerous acini and which are separated from neighboring TDLU by specialized stroma. b Breast tissue with complete lobular involution shows scattered, sparse lobules containing few acini. Scale bars, 500 μm. Modified with permission from [4]

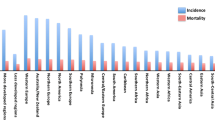

A recent study investigated pathological characteristics of a large cohort of women who had breast biopsies with benign findings (benign breast disease, BBD) at the Mayo Clinic [57]. Besides evaluating the standard features such as extent of epithelial proliferation and the presence or absence of atypia in these samples, this study noted the extent of lobular involution that had occurred in the normal breast lobules, and found that lobular involution was associated with a significantly reduced risk of breast cancer [4]. While this finding is consistent with the widespread understanding that lobules (or TDLUs) are the anatomic substructure that gives rise to breast cancer [58], this study was particularly significant in that progressive degrees of involution were associated with reduced cancer risk in high-risk subsets defined by age, atypia, reproductive history or family history (Fig. 4). For example, women over age 55 without demonstrable lobular involution had a 3-fold increased risk of breast cancer over same-aged women with complete involution (Fig. 4). Of note, about 5% of women before age 50 had complete involution of their breast tissue, while complete involution was seen in more than 20% of women aged 50–59, presumably coinciding with menopause [4]. Interestingly, the step-up in completion of involution around age 50 coincides with the well-recognized slowing in the rate of increase of breast cancer at that age, raising the possibility that involution is contributing to this phenomenon [59]. The results of this study were recently corroborated in an analysis of patient samples from the Nurses’ Health Study, which found that smaller lobular size was associated with decreased risk of cancer [60].

Association of breast cancer risk with lobular involution. Relative risks (as indicated) and their 95% confidence intervals (error bars) reflect the observed number of events compared with the number of expected events on the basis of Iowa Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) data. All results account for the effects of age and calendar period. a Involution and histology. b Involution and age. N = no involution; P = partial involution; C = complete involution; NP = nonproliferative; PDWA = proliferative disease without atypia; AH = atypical hyperplasia. Reproduced with permission from [4].

Conclusions and Future Directions

Investigations of postlactational involution using genetic mouse models have revealed an incredible complexity to the process: modulation of more than 50 different genes, through knockout or introduction of a breast-specific transgene, has been found to delay or accelerate postlactational involution. That so many distinct molecular pathways are involved in regulation of postlactational involution in a nonredundant fashion indicates the complexity of this developmental process; that so many of the models also show a tumor developmental phenotype shows how deregulation of developmental pathways can be a stimulus for cancer development and progression. At present, the bulk of the evidence points to a correlation between delayed postlactational involution and increased cancer formation, suggesting tumor-promoting microenvironmental influences within the postlactational gland; this interpretation is consistent with the hypothesis that postlactational involution may underlie the phenomenon of pregnancy-associated breast cancer [17]. However, the corresponding expectation that premature involution should therefore be associated with decreased tumorigenesis is not as clear. It should be noted that the tumor phenotype has not been established for many genetic mouse models showing altered postlactational involution; a better understanding of the individual signals linking postlactational involution and tumorigenesis will likely follow from a better characterization of these models, as well as from characterization of postlactational defects in traditional mammary tumor models.

Lobular involution, while recognized as a physiological process for some time, has only recently been linked to cancer development. Unlike postlactational involution, very little is known about the signaling processes that control lobular involution, or even why lobular involution is assocated with decreased cancer risk, although a simplistic possibility is that removal of epithelial cells eliminates the progenitor population for tumor formation. A curious aspect to the newly identified relationship between lobular involution and breast cancer is that lobular involution appears to be an age-related protective process. While cancer incidence usually increases with age, and so aging can be seen as a general risk factor, it appears that the failure of breast aging in postmenopausal women is related to increased risk of cancer development. Much additional research is required to understand how lobular involution is induced, why some women initiate lobular involution before menopause while others fail to undergo lobular involution even after menopause, and how lobular involution protects from breast cancer. A better understanding of these processes will help to inform individualized patient risk stratification, and may ultimately lead to medical interventions designed to induce lobular involution for the physiological prevention of breast cancer [59].

Abbreviations

- ATF4:

-

activating transcription factor 4

- C/EBPδ:

-

CCAAT/Enhancer Binding Protein δ

- Cox-2:

-

cyclooxygenase-2

- CSF-1:

-

colony stimulating factor-1

- ECM:

-

extracellular matrix

- EGFR:

-

epidermal growth factor receptor

- FGF4:

-

fibroblast growth factor 4

- IGF:

-

insulin-like growth factor

- IKK2:

-

IκB kinase 2/β

- IL-6:

-

interleukin-6

- IL-10:

-

interleukin-10

- IRF-1:

-

interferon regulatory factor-1

- LAR:

-

leukocyte antigen related

- LIF:

-

leukemia inhibitory factor

- Mfge8:

-

Milk fat globule-EGF-factor 8

- MMP-3:

-

matrix metalloproteinase-3

- TA1:

-

metastasis-associated protein 1

- MUC1:

-

mucin

- Plg:

-

plasminogen

- RANK:

-

receptor activator of nuclear factor-κB

- SOCS3:

-

suppressor of cytokine signaling 3

- STAT3:

-

signal transducer and activator of transcription 3

- STAT5a:

-

signal transducer and activator of transcription 5a

- TBRII:

-

transforming growth factor β receptor II

- TGFα:

-

transforming growth factor alpha

- TGFβ:

-

transforming growth factor β

- VDR:

-

vitamin D3 receptor

References

Fata JE, Werb Z, Bissell MJ. Regulation of mammary gland branching morphogenesis by the extracellular matrix and its remodeling enzymes. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6(1):1–11.

Watson CJ. Post-lactational mammary gland regression: molecular basis and implications for breast cancer. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2006;8(32):1–15. doi:10.1017/S1462399406000196.

Hutson SW, Cowen PN, Bird CC. Morphometric studies of age related changes in normal human breast and their significance for evolution of mammary cancer. J Clin Pathol. 1985;38(3):281–7. doi:10.1136/jcp.38.3.281.

Milanese TR, Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, Frost MH, Vierkant RA, Maloney SD, et al. Age-related lobular involution and risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(22):1600–7.

Watson CJ. Involution: apoptosis and tissue remodelling that convert the mammary gland from milk factory to a quiescent organ. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8(2):203. doi:10.1186/bcr1401.

Marti A, Feng Z, Altermatt HJ, Jaggi R. Milk accumulation triggers apoptosis of mammary epithelial cells. Eur J Cell Biol. 1997;73(2):158–65.

Li M, Liu X, Robinson G, Bar-Peled U, Wagner KU, Young WS, et al. Mammary-derived signals activate programmed cell death during the first stage of mammary gland involution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(7):3425–30. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.7.3425.

Baxter FO, Neoh K, Tevendale MC. The beginning of the end: death signaling in early involution. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2007;12(1):3–13. doi:10.1007/s10911-007-9033-9.

Feng Z, Marti A, Jehn B, Altermatt HJ, Chicaiza G, Jaggi R. Glucocorticoid and progesterone inhibit involution and programmed cell death in the mouse mammary gland. J Cell Biol. 1995;131(4):1095–103. doi:10.1083/jcb.131.4.1095.

Green KA, Lund LR. ECM degrading proteases and tissue remodelling in the mammary gland. Bioessays. 2005;27(9):894–903. doi:10.1002/bies.20281.

Almholt K, Green KA, Juncker-Jensen A, Nielsen BS, Lund LR, Romer J. Extracellular proteolysis in transgenic mouse models of breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2007;12(1):83–97. doi:10.1007/s10911-007-9040-x.

Clarkson RW, Watson CJ. Microarray analysis of the involution switch. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2003;8(3):309–19. doi:10.1023/B:JOMG.0000010031.53310.92.

Clarkson RW, Wayland MT, Lee J, Freeman T, Watson CJ. Gene expression profiling of mammary gland development reveals putative roles for death receptors and immune mediators in post-lactational regression. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6(2):R92–109. doi:10.1186/bcr754.

Stein T, Morris JS, Davies CR, Weber-Hall SJ, Duffy MA, Heath VJ, et al. Involution of the mouse mammary gland is associated with an immune cascade and an acute-phase response, involving LBP, CD14 and STAT3. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6(2):R75–91. doi:10.1186/bcr753.

Schedin P, O’Brien J, Rudolph M, Stein T, Borges V. Microenvironment of the involuting mammary gland mediates mammary cancer progression. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2007;12(1):71–82. doi:10.1007/s10911-007-9039-3.

van Kempen LC, Ruiter DJ, van Muijen GN, Coussens LM. The tumor microenvironment: a critical determinant of neoplastic evolution. Eur J Cell Biol. 2003;82(11):539–48. doi:10.1078/0171-9335-00346.

Schedin P. Pregnancy-associated breast cancer and metastasis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006;6(4):281–91. doi:10.1038/nrc1839.

Bemis LT, Schedin P. Reproductive state of rat mammary gland stroma modulates human breast cancer cell migration and invasion. Cancer Res. 2000;60(13):3414–8.

McDaniel SM, Rumer KK, Biroc SL, Metz RP, Singh M, Porter W, et al. Remodeling of the mammary microenvironment after lactation promotes breast tumor cell metastasis. Am J Pathol. 2006;168(2):608–20. doi:10.2353/ajpath.2006.050677.

Schedin P, Mitrenga T, McDaniel S, Kaeck M. Mammary ECM composition and function are altered by reproductive state. Mol Carcinog. 2004;41(4):207–20. doi:10.1002/mc.20058.

Song J, Sapi E, Brown W, Nilsen J, Tartaro K, Kacinski BM, et al. Roles of Fas and Fas ligand during mammary gland remodeling. J Clin Invest. 2000;106(10):1209–20. doi:10.1172/JCI10411.

Zhao L, Melenhorst JJ, Hennighausen L. Loss of interleukin 6 results in delayed mammary gland involution: a possible role for mitogen-activated protein kinase and not signal transducer and activator of transcription 3. Mol Endocrinol. 2002;16(12):2902–12. doi:10.1210/me.2001-0330.

Sohn BH, Moon HB, Kim TY, Kang HS, Bae YS, Lee KK, et al. Interleukin-10 up-regulates tumour-necrosis-factor-alpha-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) gene expression in mammary epithelial cells at the involution stage. Biochem J. 2001;360(Pt 1):31–8. doi:10.1042/0264-6021:3600031.

Kritikou EA, Sharkey A, Abell K, Came PJ, Anderson E, Clarkson RW, et al. A dual, non-redundant, role for LIF as a regulator of development and STAT3-mediated cell death in mammary gland. Development. 2003;130(15):3459–68. doi:10.1242/dev.00578.

Nguyen AV, Pollard JW. Transforming growth factor beta3 induces cell death during the first stage of mammary gland involution. Development. 2000;127(14):3107–18.

Jager R, Herzer U, Schenkel J, Weiher H. Overexpression of Bcl-2 inhibits alveolar cell apoptosis during involution and accelerates c-myc-induced tumorigenesis of the mammary gland in transgenic mice. Oncogene. 1997;15(15):1787–95. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201353.

Schorr K, Li M, Bar-Peled U, Lewis A, Heredia A, Lewis B, et al. Gain of Bcl-2 is more potent than bax loss in regulating mammary epithelial cell survival in vivo. Cancer Res. 1999;59(11):2541–5.

Atabai K, Fernandez R, Huang X, Ueki I, Kline A, Li Y, et al. Mfge8 is critical for mammary gland remodeling during involution. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16(12):5528–37. doi:10.1091/mbc.E05-02-0128.

Hanayama R, Nagata S. Impaired involution of mammary glands in the absence of milk fat globule EGF factor 8. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102(46):16886–91. doi:10.1073/pnas.0508599102.

Talhouk RS, Bissell MJ, Werb Z. Coordinated expression of extracellular matrix-degrading proteinases and their inhibitors regulates mammary epithelial function during involution. J Cell Biol. 1992;118(5):1271–82. doi:10.1083/jcb.118.5.1271.

Talhouk RS, Chin JR, Unemori EN, Werb Z, Bissell MJ. Proteinases of the mammary gland: developmental regulation in vivo and vectorial secretion in culture. Development. 1991;112(2):439–49.

Alexander CM, Howard EW, Bissell MJ, Werb Z. Rescue of mammary epithelial cell apoptosis and entactin degradation by a tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 transgene. J Cell Biol. 1996;135(6 Pt 1):1669–77. doi:10.1083/jcb.135.6.1669.

Alexander CM, Selvarajan S, Mudgett J, Werb Z. Stromelysin-1 regulates adipogenesis during mammary gland involution. J Cell Biol. 2001;152(4):693–703. doi:10.1083/jcb.152.4.693.

Lund LR, Bjorn SF, Sternlicht MD, Nielsen BS, Solberg H, Usher PA, et al. Lactational competence and involution of the mouse mammary gland require plasminogen. Development. 2000;127(20):4481–92.

Sympson CJ, Talhouk RS, Alexander CM, Chin JR, Clift SM, Bissell MJ, et al. Targeted expression of stromelysin-1 in mammary gland provides evidence for a role of proteinases in branching morphogenesis and the requirement for an intact basement membrane for tissue-specific gene expression. J Cell Biol. 1994;125(3):681–93. doi:10.1083/jcb.125.3.681.

Green KA, Nielsen BS, Castellino FJ, Romer J, Lund LR. Lack of plasminogen leads to milk stasis and premature mammary gland involution during lactation. Dev Biol. 2006;299(1):164–75. doi:10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.07.021.

Muller WJ, Sinn E, Pattengale PK, Wallace R, Leder P. Single-step induction of mammary adenocarcinoma in transgenic mice bearing the activated c-neu oncogene. Cell. 1988;54(1):105–15. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(88)90184-5.

Lazar H, Baltzer A, Gimmi C, Marti A, Jaggi R. Over-expression of erbB-2/neu is paralleled by inhibition of mouse-mammary-epithelial-cell differentiation and developmental apoptosis. Int J Cancer. 2000;85(4):578–83. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0215(20000215)85:4<578::AID-IJC21>3.0.CO;2-S.

Hutchinson J, Jin J, Cardiff RD, Woodgett JR, Muller WJ. Activation of Akt (protein kinase B) in mammary epithelium provides a critical cell survival signal required for tumor progression. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21(6):2203–12. doi:10.1128/MCB.21.6.2203-2212.2001.

Hutchinson JN, Jin J, Cardiff RD, Woodgett JR, Muller WJ. Activation of Akt-1 (PKB-alpha) can accelerate ErbB-2-mediated mammary tumorigenesis but suppresses tumor invasion. Cancer Res. 2004;64(9):3171–8. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-3465.

Ackler S, Ahmad S, Tobias C, Johnson MD, Glazer RI. Delayed mammary gland involution in MMTV-AKT1 transgenic mice. Oncogene. 2002;21(2):198–206. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1205052.

Schwertfeger KL, Richert MM, Anderson SM. Mammary gland involution is delayed by activated Akt in transgenic mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2001;15(6):867–81. doi:10.1210/me.15.6.867.

Shibata MA, Liu ML, Knudson MC, Shibata E, Yoshidome K, Bandey T, et al. Haploid loss of bax leads to accelerated mammary tumor development in C3(1)/SV40-TAg transgenic mice: reduction in protective apoptotic response at the preneoplastic stage. EMBO J. 1999;18(10):2692–701. doi:10.1093/emboj/18.10.2692.

Furth PA, Bar-Peled U, Li M, Lewis A, Laucirica R, Jager R, et al. Loss of anti-mitotic effects of Bcl-2 with retention of anti-apoptotic activity during tumor progression in a mouse model. Oncogene. 1999;18(47):6589–96. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1203073.

Radisky DC, Bissell MJ. Matrix metalloproteinase-induced genomic instability. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16(1):45–50. doi:10.1016/j.gde.2005.12.011.

Sun Y, Strizzi L, Raafat A, Hirota M, Bianco C, Feigenbaum L, et al. Overexpression of human Cripto-1 in transgenic mice delays mammary gland development and differentiation and induces mammary tumorigenesis. Am J Pathol. 2005;167(2):585–97.

Wechselberger C, Strizzi L, Kenney N, Hirota M, Sun Y, Ebert A, et al. Human Cripto-1 overexpression in the mouse mammary gland results in the development of hyperplasia and adenocarcinoma. Oncogene. 2005;24(25):4094–105.

Sternlicht MD, Lochter A, Sympson CJ, Huey B, Rougier JP, Gray JW, et al. The stromal proteinase MMP3/stromelysin-1 promotes mammary carcinogenesis. Cell. 1999;98(2):137–46. doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81009-0.

Sympson CJ, Bissell MJ, Werb Z. Mammary gland tumor formation in transgenic mice overexpressing stromelysin-1. Semin Cancer Biol. 1995;6(3):159–63. doi:10.1006/scbi.1995.0022.

Stewart TA, Pattengale PK, Leder P. Spontaneous mammary adenocarcinomas in transgenic mice that carry and express MTV/myc fusion genes. Cell. 1984;38(3):627–37. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(84)90257-5.

Boudreau N, Werb Z, Bissell MJ. Suppression of apoptosis by basement membrane requires three-dimensional tissue organization and withdrawal from the cell cycle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93(8):3509–13. doi:10.1073/pnas.93.8.3509.

Hennighausen L, Robinson GW. Signaling pathways in mammary gland development. Dev Cell. 2001;1(4):467–75. doi:10.1016/S1534-5807(01)00064-8.

Russo J, Russo IH. Development of the human breast. Maturitas. 2004;49(1):2–15. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2004.04.011.

Vorrherr H. The breast: morphology, physiology, and lactation. New York: Academic; 1974.

Howard BA, Gusterson BA. Human breast development. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia. 2000;5(2):119–37. doi:10.1023/A:1026487120779.

Geschickter C. Diseases of the breast. Philadelphia: J.B. Lipincott Co; 1945.

Hartmann LC, Sellers TA, Frost MH, Lingle WL, Degnim AC, Ghosh K, et al. Benign breast disease and the risk of breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(3):229–37. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa044383.

Wellings SR, Jensen HM, Marcum RG. An atlas of subgross pathology of the human breast with special reference to possible precancerous lesions. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1975;55(2):231–73.

Henson DE, Tarone RE, Nsouli H. Lobular involution: the physiological prevention of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98(22):1589–90.

Baer HJ, Collins LC, Connolly JL, Colditz GA, Schnitt SJ, Tamimi RM. Lobule type and subsequent breast cancer risk: Results from the Nurses’ Health Studies. Cancer. 2009;115(7):1404–11. doi:10.1002/cncr.24167.

Maroulakou IG, Oemler W, Naber SP, Klebba I, Kuperwasser C, Tsichlis PN. Distinct roles of the three Akt isoforms in lactogenic differentiation and involution. J Cell Physiol. 2008;217(2):468–77. doi:10.1002/jcp.21518.

Maroulakou IG, Oemler W, Naber SP, Tsichlis PN. Akt1 ablation inhibits, whereas Akt2 ablation accelerates, the development of mammary adenocarcinomas in mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV)-ErbB2/neu and MMTV-polyoma middle T transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67(1):167–77. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3782.

Chang MY, Boulden J, Sutanto-Ward E, Duhadaway JB, Soler AP, Muller AJ, et al. Bin1 ablation in mammary gland delays tissue remodeling and drives cancer progression. Cancer Res. 2007;67(1):100–7. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2742.

Cabodi S, Tinnirello A, Di Stefano P, Bisaro B, Ambrosino E, Castellano I, et al. p130Cas as a new regulator of mammary epithelial cell proliferation, survival, and HER2-neu oncogene-dependent breast tumorigenesis. Cancer Res. 2006;66(9):4672–80. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2909.

Imbert A, Eelkema R, Jordan S, Feiner H, Cowin P. Delta N89 beta-catenin induces precocious development, differentiation, and neoplasia in mammary gland. J Cell Biol. 2001;153(3):555–68. doi:10.1083/jcb.153.3.555.

Ma ZQ, Chua SS, DeMayo FJ, Tsai SY. Induction of mammary gland hyperplasia in transgenic mice over-expressing human Cdc25B. Oncogene. 1999;18(32):4564–76. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202809.

Yao Y, Slosberg ED, Wang L, Hibshoosh H, Zhang YJ, Xing WQ, et al. Increased susceptibility to carcinogen-induced mammary tumors in MMTV-Cdc25B transgenic mice. Oncogene. 1999;18(37):5159–66. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202908.

Thangaraju M, Rudelius M, Bierie B, Raffeld M, Sharan S, Hennighausen L, et al. C/EBPdelta is a crucial regulator of pro-apoptotic gene expression during mammary gland involution. Development. 2005;132(21):4675–85. doi:10.1242/dev.02050.

Liu CH, Chang SH, Narko K, Trifan OC, Wu MT, Smith E, et al. Overexpression of cyclooxygenase-2 is sufficient to induce tumorigenesis in transgenic mice. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(21):18563–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M010787200.

Kirma N, Luthra R, Jones J, Liu YG, Nair HB, Mandava U, et al. Overexpression of the colony-stimulating factor (CSF-1) and/or its receptor c-fms in mammary glands of transgenic mice results in hyperplasia and tumor formation. Cancer Res. 2004;64(12):4162–70. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2971.

Brandt R, Eisenbrandt R, Leenders F, Zschiesche W, Binas B, Juergensen C, et al. Mammary gland specific hEGF receptor transgene expression induces neoplasia and inhibits differentiation. Oncogene. 2000;19(17):2129–37. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1203520.

Marozkina NV, Stiefel SM, Frierson HF Jr, Parsons SJ. MMTV-EGF receptor transgene promotes preneoplastic conversion of multiple steroid hormone-responsive tissues. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103(6):2010–8. doi:10.1002/jcb.21591.

Munarini N, Jager R, Abderhalden S, Zuercher G, Rohrbach V, Loercher S, et al. Altered mammary epithelial development, pattern formation and involution in transgenic mice expressing the EphB4 receptor tyrosine kinase. J Cell Sci. 2002;115(Pt 1):25–37.

Morini M, Astigiano S, Mora M, Ricotta C, Ferrari N, Mantero S, et al. Hyperplasia and impaired involution in the mammary gland of transgenic mice expressing human FGF4. Oncogene. 2000;19(52):6007–14. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204011.

Zhao L, Hart S, Cheng J, Melenhorst JJ, Bierie B, Ernst M, et al. Mammary gland remodeling depends on gp130 signaling through Stat3 and MAPK. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(42):44093–100. doi:10.1074/jbc.M313131200.

Hadsell DL, Greenberg NM, Fligger JM, Baumrucker CR, Rosen JM. Targeted expression of des(1–3) human insulin-like growth factor I in transgenic mice influences mammary gland development and IGF-binding protein expression. Endocrinology. 1996;137(1):321–30. doi:10.1210/en.137.1.321.

Hadsell DL, Torres DT, Lawrence NA, George J, Parlow AF, Lee AV, et al. Overexpression of des(1–3) insulin-like growth factor 1 in the mammary glands of transgenic mice delays the loss of milk production with prolonged lactation. Biol Reprod. 2005;73(6):1116–25. doi:10.1095/biolreprod.105.043992.

Neuenschwander S, Schwartz A, Wood TL, Roberts CT Jr, Hennighausen L, LeRoith D. Involution of the lactating mammary gland is inhibited by the IGF system in a transgenic mouse model. J Clin Invest. 1996;97(10):2225–32. doi:10.1172/JCI118663.

Hadsell DL, Murphy KL, Bonnette SG, Reece N, Laucirica R, Rosen JM. Cooperative interaction between mutant p53 and des(1–3) IGF-I accelerates mammary tumorigenesis. Oncogene. 2000;19(7):889–98. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1203386.

Moorehead RA, Fata JE, Johnson MB, Khokha R. Inhibition of mammary epithelial apoptosis and sustained phosphorylation of Akt/PKB in MMTV-IGF-II transgenic mice. Cell Death Differ. 2001;8(1):16–29. doi:10.1038/sj.cdd.4400762.

Carboni JM, Lee AV, Hadsell DL, Rowley BR, Lee FY, Bol DK, et al. Tumor development by transgenic expression of a constitutively active insulin-like growth factor I receptor. Cancer Res. 2005;65(9):3781–7. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-4602.

Baxter FO, Came PJ, Abell K, Kedjouar B, Huth M, Rajewsky K, et al. IKKbeta/2 induces TWEAK and apoptosis in mammary epithelial cells. Development. 2006;133(17):3485–94. doi:10.1242/dev.02502.

Wagner KU, Krempler A, Triplett AA, Qi Y, George NM, Zhu J, et al. Impaired alveologenesis and maintenance of secretory mammary epithelial cells in Jak2 conditional knockout mice. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24(12):5510–20. doi:10.1128/MCB.24.12.5510-5520.2004.

Bagheri-Yarmand R, Talukder AH, Wang RA, Vadlamudi RK, Kumar R. Metastasis-associated protein 1 deregulation causes inappropriate mammary gland development and tumorigenesis. Development. 2004;131(14):3469–79. doi:10.1242/dev.01213.

Schroeder JA, Masri AA, Adriance MC, Tessier JC, Kotlarczyk KL, Thompson MC, et al. MUC1 overexpression results in mammary gland tumorigenesis and prolonged alveolar differentiation. Oncogene. 2004;23(34):5739–47. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1207713.

Toyo-oka K, Bowen TJ, Hirotsune S, Li Z, Jain S, Ota S, et al. Mnt-deficient mammary glands exhibit impaired involution and tumors with characteristics of myc overexpression. Cancer Res. 2006;66(11):5565–73. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2683.

Hurlin PJ, Zhou ZQ, Toyo-oka K, Ota S, Walker WL, Hirotsune S, et al. Deletion of Mnt leads to disrupted cell cycle control and tumorigenesis. EMBO J. 2003;22(18):4584–96. doi:10.1093/emboj/cdg442.

Hu C, Dievart A, Lupien M, Calvo E, Tremblay G, Jolicoeur P. Overexpression of activated murine Notch1 and Notch3 in transgenic mice blocks mammary gland development and induces mammary tumors. Am J Pathol. 2006;168(3):973–90. doi:10.2353/ajpath.2006.050416.

Kiaris H, Politi K, Grimm LM, Szabolcs M, Fisher P, Efstratiadis A, et al. Modulation of notch signaling elicits signature tumors and inhibits hras1-induced oncogenesis in the mouse mammary epithelium. Am J Pathol. 2004;165(2):695–705.

Jerry DJ, Kuperwasser C, Downing SR, Pinkas J, He C, Dickinson E, et al. Delayed involution of the mammary epithelium in BALB/c-p53null mice. Oncogene. 1998;17(18):2305–12. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1202157.

Kuperwasser C, Hurlbut GD, Kittrell FS, Dickinson ES, Laucirica R, Medina D, et al. Development of spontaneous mammary tumors in BALB/c p53 heterozygous mice. A model for Li-Fraumeni syndrome. Am J Pathol. 2000;157(6):2151–9.

Li G, Robinson GW, Lesche R, Martinez-Diaz H, Jiang Z, Rozengurt N, et al. Conditional loss of PTEN leads to precocious development and neoplasia in the mammary gland. Development. 2002;129(17):4159–70.

Gonzalez-Suarez E, Branstetter D, Armstrong A, Dinh H, Blumberg H, Dougall WC. RANK overexpression in transgenic mice with mouse mammary tumor virus promoter-controlled RANK increases proliferation and impairs alveolar differentiation in the mammary epithelia and disrupts lumen formation in cultured epithelial acini. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27(4):1442–54. doi:10.1128/MCB.01298-06.

Chapman RS, Lourenco P, Tonner E, Flint D, Selbert S, Takeda K, et al. The role of Stat3 in apoptosis and mammary gland involution. Conditional deletion of Stat3. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2000;480:129–38. doi:10.1007/0-306-46832-8_16.

Humphreys RC, Bierie B, Zhao L, Raz R, Levy D, Hennighausen L. Deletion of Stat3 blocks mammary gland involution and extends functional competence of the secretory epithelium in the absence of lactogenic stimuli. Endocrinology. 2002;143(9):3641–50. doi:10.1210/en.2002-220224.

Bierie B, Gorska AE, Stover DG, Moses HL. TGF-beta promotes cell death and suppresses lactation during the second stage of mammary involution. J Cell Physiol. 2009;219(1):57–68. doi:10.1002/jcp.21646.

Gorska AE, Jensen RA, Shyr Y, Aakre ME, Bhowmick NA, Moses HL. Transgenic mice expressing a dominant-negative mutant type II transforming growth factor-beta receptor exhibit impaired mammary development and enhanced mammary tumor formation. Am J Pathol. 2003;163(4):1539–49.

Bierie B, Stover DG, Abel TW, Chytil A, Gorska AE, Aakre M, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta regulates mammary carcinoma cell survival and interaction with the adjacent microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2008;68(6):1809–19. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5597.

Forrester E, Chytil A, Bierie B, Aakre M, Gorska AE, Sharif-Afshar AR, et al. Effect of conditional knockout of the type II TGF-beta receptor gene in mammary epithelia on mammary gland development and polyomavirus middle T antigen induced tumor formation and metastasis. Cancer Res. 2005;65(6):2296–302. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3272.

Sandgren EP, Schroeder JA, Qui TH, Palmiter RD, Brinster RL, Lee DC. Inhibition of mammary gland involution is associated with transforming growth factor alpha but not c-myc-induced tumorigenesis in transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 1995;55(17):3915–27.

Zinser GM, Welsh J. Accelerated mammary gland development during pregnancy and delayed postlactational involution in vitamin D3 receptor null mice. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18(9):2208–23. doi:10.1210/me.2003-0469.

Zinser GM, Suckow M, Welsh J. Vitamin D receptor (VDR) ablation alters carcinogen-induced tumorigenesis in mammary gland, epidermis and lymphoid tissues. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;97(1–2):153–64. doi:10.1016/j.jsbmb.2005.06.024.

Zinser GM, Welsh J. Vitamin D receptor status alters mammary gland morphology and tumorigenesis in MMTV-neu mice. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25(12):2361–72. doi:10.1093/carcin/bgh271.

Bagheri-Yarmand R, Vadlamudi RK, Kumar R. Activating transcription factor 4 overexpression inhibits proliferation and differentiation of mammary epithelium resulting in impaired lactation and accelerated involution. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(19):17421–9. doi:10.1074/jbc.M300761200.

Faraldo MM, Deugnier MA, Tlouzeau S, Thiery JP, Glukhova MA. Perturbation of beta1-integrin function in involuting mammary gland results in premature dedifferentiation of secretory epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13(10):3521–31. doi:10.1091/mbc.E02-02-0086.

White DE, Kurpios NA, Zuo D, Hassell JA, Blaess S, Mueller U, et al. Targeted disruption of beta1-integrin in a transgenic mouse model of human breast cancer reveals an essential role in mammary tumor induction. Cancer Cell. 2004;6(2):159–70. doi:10.1016/j.ccr.2004.06.025.

Walton KD, Wagner KU, Rucker EB 3rd, Shillingford JM, Miyoshi K, Hennighausen L. Conditional deletion of the bcl-x gene from mouse mammary epithelium results in accelerated apoptosis during involution but does not compromise cell function during lactation. Mech Dev. 2001;109(2):281–93. doi:10.1016/S0925-4773(01)00549-4.

Chapman RS, Duff EK, Lourenco PC, Tonner E, Flint DJ, Clarke AR, et al. A novel role for IRF-1 as a suppressor of apoptosis. Oncogene. 2000;19(54):6386–91. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1204016.

Schaapveld RQ, Schepens JT, Robinson GW, Attema J, Oerlemans FT, Fransen JA, et al. Impaired mammary gland development and function in mice lacking LAR receptor-like tyrosine phosphatase activity. Dev Biol. 1997;188(1):134–46. doi:10.1006/dbio.1997.8630.

Robinson GW, Pacher-Zavisin M, Zhu BM, Yoshimura A, Hennighausen L. Socs 3 modulates the activity of the transcription factor Stat3 in mammary tissue and controls alveolar homeostasis. Dev Dyn. 2007;236(3):654–61. doi:10.1002/dvdy.21058.

Humphreys RC, Hennighausen L. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 5a influences mammary epithelial cell survival and tumorigenesis. Cell Growth Differ. 1999;10(10):685–94.

Ren S, Cai HR, Li M, Furth PA. Loss of Stat5a delays mammary cancer progression in a mouse model. Oncogene. 2002;21(27):4335–9. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1205484.

Fata JE, Leco KJ, Voura EB, Yu HY, Waterhouse P, Murphy G, et al. Accelerated apoptosis in the Timp-3-deficient mammary gland. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(6):831–41.

Acknowledgements

The authors were supported by the National Cancer Institute (CA122086 and CA128660 to DCR, CA132879 to LCH and DCR, and the Breast Specialized Program of Research Excellence [SPORE] CA116201 to LCH and DCR), the Department of Defense (FEDDAMD17-02-1-0473to LCH) and the Susan B. Komen foundation (FAS0703855 to DCR). Figure 3 was previously published in reference [4]. We thank Theresa Mooney and Dr. Jamie Bascom for the images used in Fig. 1.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Radisky, D.C., Hartmann, L.C. Mammary Involution and Breast Cancer Risk: Transgenic Models and Clinical Studies. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 14, 181–191 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10911-009-9123-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10911-009-9123-y