Abstract

Cognitive brain functions including sensory processing and control of behavior are understood as “neurocomputation” in axonal–dendritic synaptic networks of “integrate-and-fire” neurons. Cognitive neurocomputation with consciousness is accompanied by 30- to 90-Hz gamma synchrony electroencephalography (EEG), and non-conscious neurocomputation is not. Gamma synchrony EEG derives largely from neuronal groups linked by dendritic–dendritic gap junctions, forming transient syncytia (“dendritic webs”) in input/integration layers oriented sideways to axonal–dendritic neurocomputational flow. As gap junctions open and close, a gamma-synchronized dendritic web can rapidly change topology and move through the brain as a spatiotemporal envelope performing collective integration and volitional choices correlating with consciousness. The “conscious pilot” is a metaphorical description for a mobile gamma-synchronized dendritic web as vehicle for a conscious agent/pilot which experiences and assumes control of otherwise non-conscious auto-pilot neurocomputation.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction: Gamma synchrony and the “conscious pilot”

Cognitive brain functions are accounted for by information processing in networks of neurons—“neurocomputation.” In each neuron, dendrites and the cell body/soma receive synaptic inputs and integrate them to a threshold for axonal firings as outputs—“integrate and fire.” Cognitive brain functions are thus understood as “neurocomputation” in networks of “integrate-and-fire” neurons.

Despite this understanding, an explanation for conscious awareness eludes modern science. Illustrating this point, philosopher David Chalmers [1] has characterized non-conscious cognitive brain functions as the “easy problems,” including the brain’s abilities to non-consciously discriminate, categorize, and react to sensory stimuli, integrate information, focus attention, and control behavior. Non-conscious easy problem cognitive functions are largely habitual and also expressed as “zombie” modes [2] or “auto-pilot” [3].Footnote 1 Chalmers explains that the so-called easy problems are not really that easy but at least seem directly amenable to “neurocomputation,” i.e., the brain’s integrate-and-fire neurons and synapses acting like “bit states” and switches in computers. Neurocomputation can explain non-conscious easy problem, zombie mode, and auto-pilot processes.

The “hard problem” according to Chalmers is the question of how the brain produces conscious control and experience, i.e., phenomenal awareness with subjective feelings, composed of what philosophers call “qualia.” The hard problem refers to the fact that conscious control and experience do not naturally derive from neurocomputation. Without addressing the hard problem per se, neuroscientists aim to identify a “neural correlate of consciousness” (NCC), brain systems active concomitantly with conscious experience [4]. This paper presents a new model of the NCC as a mobile integrator moving through dendritic/somatic input/integration layers of the brain’s neurocomputational networks.

A key point is that non-conscious auto-pilot modes (easy problems, zombie modes) and conscious control and experience (hard problem) are not always separate and distinct. At times, non-conscious auto-pilot modes become driven or accompanied by conscious experience. For example, we often perform complex habitual behaviors like walking or driving while daydreaming, seemingly on auto-pilot with consciousness somewhere else. But when novelty occurs we consciously perceive the scene and assume conscious control—consciousness is able to “tune into and take over” non-conscious processes. So rather than a distinction between non-conscious auto-pilot modes on the one hand and conscious experience on the other, the essential distinction is actually between cognitive neurocomputation which at any given moment is, or is not, accompanied by some added fleeting feature (the “conscious pilot”) which conveys conscious experience and choice.

The best measurable feature correlating with consciousness (i.e., the NCC) is coherent electrical activity in a particular frequency band of the electroencephalogram (EEG).Footnote 2 The EEG records tiny brain-generated voltage fluctuations from scalp or brain surface electrodes, producing a complex continually varying signal.Footnote 3 An important parameter is the degree of coherence or phase synchrony among voltage fluctuations recorded from different electrodes at any specific EEG frequency. Phase synchrony at various EEG frequencies can occur locally within one brain region, between neighboring and long-range regions, or globally distributed among many spatially separated brain regions.

In the late 1980s, Wolf Singer and colleagues [5, 6] found specific, phase-synchronized EEG in cats’ visual cortex which was strongly correlated with particular visual stimulation. The phase synchrony they found occurred at around 40 Hz, in the gamma frequency band of the EEG, and became known as “coherent 40 Hz” (gamma covering the range from 30 to 90 Hz). Subsequent studies have shown gamma synchrony in various brain locations correlating with conscious perception, motor control, language, working memory, face and word recognition, sleep/wake and dream cycles, and binding—the issue of how neurocomputational representations occurring in different brain regions and at slightly different moments are bound together in a unified conscious percept [7–19].Footnote 4

Location and distribution of gamma synchrony within the brain can change dynamically, shifting on timescales of hundreds of milliseconds or faster [7, 20]. Specific modalities of conscious content reflect particular locations/distributions of gamma synchrony. For example, conscious smell occurs when odorant molecules induce gamma synchrony among olfactory bulb dendrites [21–23]. With conscious pleasure and reward, gamma synchrony is occurring in ventral tegmentum and nucleus accumbens [24].

When we are conscious of our surroundings, neurocomputational sensory arousal activity ascends via thalamus to cortex and then through other cortical areas in feed-forward and feedback circuits.Footnote 5 These bottom-up and top-down recurrent neurocomputational networks are proposed to represent the world and mediate consciousness, e.g., in a “global workspace” [25–27]. But thalamocortical arousal is neither necessary nor sufficient for consciousness. We often process sensory information non-consciously while on auto-pilot, e.g., while we drive, walk, or engage in other habitual behaviors. In these situations, thalamocortical arousal and sensory processing continue without consciousness (and without gamma synchrony) [28].Footnote 6 And consciousness occurs without thalamocortical arousal, e.g., in internally generated conscious states like memory recall and daydreaming owing to ongoing cortical–cortical dynamics [28].

The best measurable correlate of consciousness is long-range (e.g., cortical–cortical) gamma synchrony. In animals and surgical patients undergoing general anesthesia, gamma synchrony between frontal and posterior cortex is the specific marker which disappears with loss of consciousness and returns upon awakening [29, 30].Footnote 7 In what may be considered enhanced or optimized levels of consciousness, highest amplitude, frequency, and phase coherent gamma synchrony have been recorded spanning cortical regions in meditating Tibetan monks [31].

What are the brain boundaries of gamma synchrony? Using depth electrodes in animals, gamma synchrony has been found between cortical hemispheres and between cortex, thalamus, other sub-cortical regions and even spinal cord [32]. Consciousness may require some critical threshold of gamma-synchronized neurons, e.g., long range (frontal–posterior, bi-hemispheric, corticospinal, ventral tegmentum–nucleus accumbens, etc.), critical number, or distribution. Gamma synchrony and consciousness seemingly redistribute and move together around the brain, able to tune into and assume control of otherwise non-conscious functions.Footnote 8

As a metaphor, consider a passenger airplane cruising on auto-pilot. The conscious pilot is present but not directly in control nor consciously aware of the cockpit view or instrument readings. Perhaps he/she is reading a magazine, chatting in the main cabin or even sleeping and dreaming. Suddenly turbulence occurs or an alarm sounds. The conscious pilot “tunes in and takes over,” directing his/her attention to the view and instrument readings in the cockpit and assuming motor control of the plane and correcting course or elevation to avoid the turbulence. When the situation is resolved, the auto-pilot resumes monitoring and control, and the conscious pilot returns to previous activities, perhaps visiting with a flight attendant in the galley.

In the metaphorical airplane, the auto-pilot tending to the easy problems is the on-board flight computer and instruments. In the brain, non-conscious auto-pilot modes are accounted for by (e.g., thalamocortical) neurocomputation, i.e., the brain’s neuronal firings and synaptic transmissions acting like “bit states” and switches in computers.

What about the conscious pilot? Gamma synchrony is the logical candidate, correlating with consciousness and moving and redistributing throughout neurocomputational brain networks. Fully alert, attentive consciousness involving thalamocortical sensory arousal accompanied by gamma synchrony is the conscious pilot in the cockpit, perceiving the view and instrument readings and controlling the plane. Daydreaming, conscious memory, and other internally generated states would be gamma synchrony in various cortical areas, hippocampus, nucleus accumbens, etc.—the conscious pilot occupied elsewhere while the auto-pilot flies the plane.Footnote 9

But gamma synchrony (like consciousness) does not directly ensue from neurocomputation.

2 Neurocomputation: The computer-like brain and the brain-like computer

In the past half century, brain function has been understood in the context of how computers operate, and development of computers has benefited from knowledge of brain function—“neurocomputation.”

In computers, discrete electron states in silicon represent fundamental information units (e.g., “bits”) which interact, receive inputs from other states, and—according to some form of logic—produce outputs. With feedback, flows of inputs and outputs scale up to networks of networks which, like brains, solve problems, simulate reality, and regulate complex behaviors.

In the brain, discrete neuronal states enabling computation were established by Spanish neuroanatomist Santiago Ramón y Cajal [33] who showed the brain to be composed largely of individual filamentous neuronal cells, or neurons, subsequently demonstrated to communicate with other neurons by chemical synapses.Footnote 10 Cajal’s discrete neurons eclipsed the previous view of Italian scientist Camillo Golgi that the brain was a threaded-together reticulum or mesh-like syncytium of uninterrupted filamentous neuronal processes.

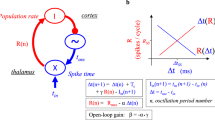

In the context of computation, Cajal’s neurons play the role of “integrate-and-fire” threshold logic devices. Neurons generally consist of multiple branched dendrites and a cell body (soma) which receive and integrate synaptic inputs to a specific voltage potential at a region on the proximal axon membrane (Fig. 1a).Footnote 11 This region, the axon hillock or axon initiation segment, has an inherent threshold which, when met by the integrated potential, triggers an action potential “firing” or “spike” as output, conveyed along the axon to the next synapse.

Three characterizations of a neuron. a Biological neuron with multiple dendrites and one cell body (soma) receiving synaptic inputs. The axon initiation segment (AIS) is where axonal spikes/firings are triggered, and a single axon branches distally to convey outputs. b Computer-based artificial neuron (e.g., a “perceptron”) with multiple weighted inputs and single branched output. c Toy neuron (see subsequent figures) showing the same essential features with three inputs on one dendrite and single axonal output which branches distally

Axonal firings or spikes do not dissipate once triggered (“all or none”) and are thus comparable to both digital outputs and inputs in computers, e.g., binary bits which convey information. In most approaches, dendritic integration beyond synaptic weighting is considered purely passive summation of weighted spike inputs and otherwise ignored. Recordings from single neurons in the brains of animals and occasionally humans show correlations between spike frequency and specific perceptions and behaviors [34]. Axonal spikes/firings are viewed as the primary currency of neurocomputation and the NCC [35]. With weighted synaptic connection strengths, neurocomputational networks of spiking neurons can account for complex non-conscious cognitive auto-pilot functions.Footnote 12

McCulloch and Pitts [36] were among the first to abstract integrate-and-fire neurons for use in computer design. The McCulloch–Pitts model neuron had multiple inputs and a single output (Fig. 1b). Inputs were integrated by passive summation to a threshold which, when reached, triggered an all-or-none binary output. With addition of adjustable input strengths, artificial neurons (e.g., the “perceptron”) arose, leading to self-organizing artificial neural networks and brain-like computers capable of adaptive learning [37]. Brain function and the computer were wed.

Figure 1c shows a toy neuron based on biological and artificial neurons. A neurocomputational network of such toy neurons is shown in Fig. 2. Binary 1 or 0 inputs (left) and outputs (top, right, bottom) correspond with axonal firings/spikes and their synaptic transmissions. Black represents neurons firing; white neurons are not firing. Arbitrary synaptic weighting and dendritic integration are not shown, and in this figure dendritic–dendritic sideways interactions are not considered. This is a simple example of neurocomputation which, in appropriate scale and organization, can account for non-conscious cognitive functions (auto-pilot).

Neurocomputation: time steps 1 and 2 in layered network of toy neurons (Fig. 1c). Synaptic inputs enter on left, spike/firing axonal outputs exit on top, bottom, and right. Black denotes firing/spike; white denotes not firing/no spike (integration not shown). Dendrites in each layer are adjacent and linked by gap junctions which, in these steps, remain closed. Hence, all neurons here function as individual integrate-and-fire threshold logic devices. For a given set of inputs, weighted connections (arbitrary, not shown) determine network behavior and measurable outputs

What about consciousness? Some authorities contend that consciousness emerges from axonal firings as outputs of critically complex neurocomputation [34, 35] or coherent volleys of axonal spikes or “neuronal firing explosions” [38]. Others place consciousness in dendrites and cell bodies/soma of neurons, i.e., in the integration phase of “integrate and fire” [39–41].Footnote 13

At the neuronal level, dendritic/somatic integration of synaptic inputs is not passive, involving complex logic functions and signal processing in dendritic spines, local dendritic regions [42–44], and intra-dendritic and somatic cytoskeletal processes [45, 46].Footnote 14 Anesthetics act almost exclusively on dendritic and cell body/somatic proteins to erase consciousness, with little or no effects on axonal firing capabilities. And coherent spike volleys/firing explosions are preceded and caused by synchronized dendritic/somatic integrations. Arguably, dendritic/somatic integration is the sub-neuronal correlate of consciousness. And dendritic/somatic integration is the origin of gamma synchrony.

3 Conscious moments and gamma “sideways synchrony”

In computers, discrete operations are performed synchronously in many parallel computational elements operating at a particular clock speed (up to 3 GHz—three billion cycles per second). Does the brain have a synchronous clocking mechanism? Is consciousness a sequence of discrete events or frames—conscious moments—clocked by gamma-synchronized brain activity?

William James [47] initially considered consciousness a sequence of “specious moments’” (but then embraced a continuous “stream of consciousness”). Alfred North Whitehead [48, 49] portrayed consciousness as a sequence of discrete events termed “occasions of experience.” The “perceptual moment” theory of Stroud [50] described consciousness as discrete events, like sequential frames of a movie.

Evidence in recent years suggests periodicities for perception and reaction times in the range of 20 to 50 ms (e.g., gamma EEG waves; 30 to 90 Hz) and others in a longer range of hundreds of milliseconds (e.g., theta EEG waves; 3 to 7 Hz), the latter consistent with saccades and the visual gestalt [51]. Woolf and Hameroff [41] and VanRullen and Koch [51] have suggested that the visual scene correlates with a series of fast gamma waves (each corresponding to specific visual components, e.g., shape, color, motion) riding on a slower theta wave. Freeman [52] characterized theta waves with finer-scale cortical dynamics as cinema-like frames of conscious content. Conscious perception may consist of theta-synchronized scenes, each composed of gamma-synchronized frames.Footnote 15 , Footnote 16 Gamma synchrony can provide sequences of discrete conscious frames or moments.

Following Singer’s work in the 1980s, authorities viewed particular networks of gamma-synchronized neurons as the NCC [4, 53]. But gamma synchrony fell from favor, not because it does not correlate with cognition and consciousness—it clearly does. Gamma synchrony was discounted because it does not correspond with axonal firings or spikes, the assumed currency of axonal–dendritic neurocomputation and the NCC [54]. Like other EEG components, gamma ensues from local field potentials, in turn derived mostly from synchronized dendritic and cell body/somatic post-synaptic potentials, i.e., integration phases of integrate-and-fire neuronal activity.

Phase synchrony at frequencies slower than gamma is readily explained through axonal–dendritic/somatic neurocomputation, i.e., post-synaptic potentials driven coherently by thalamic pacemaking, reciprocal connections, and recurrent feedback [55]. But at gamma frequency phase intervals (e.g., 25 ms for 40 Hz), synaptic delays, and variabilities in spike threshold, neurotransmitter release and axonal conduction times become problematic [56, 57]. The origin of gamma synchrony points in a sideways direction.

Brain neuronal dendrites and cell bodies/soma receive chemical synaptic inputs from axons of other neurons—the basis for axonal–dendritic feed-forward and feedback neurocomputation (Fig. 2). But dendrites also couple laterally (perpendicular, orthogonal to the flow of axonal–dendritic neurocomputation) to dendrites of neighboring neurons by gap junctions or “electrical synapses” (Fig. 3).

Gap junctions are direct windows between adjacent cells formed by paired collars of proteins called connexins [56–59] and pannexins [60]. Neurons connected by gap junctions have continuous internal cytoplasm and synchronized membranes and “behave like one giant neuron” [61]. Membrane potentials on one side of a dendritic–dendritic gap junction induce a “spikelet” or prepotential into the opposite side, integrating dendritic potentials (along with axonal inputs) to drive synchrony [62].

In the late 1990s, experiments began to show that gamma synchrony in various specific brain regions requires dendritic–dendritic gap junction coupling of groups of neurons [63–74].Footnote 17

In cortex, inter-neurons have many dendrites which form gap junction connections with up to 70 other neurons or glia [75]. Inter-neurons often have dual synapses—their axons form an inhibitory γ-aminobutyric acid chemical synapse on another neuron’s dendrite, while the same two cells share dendritic–dendritic gap junctions [73, 76, 77].Footnote 18 Dendrites arising in all directions from cell bodies of inter-neurons in cortical layers 2 through 6 form gap junctions with inter-neurons based in all other layers. A “dendritic web” of gap-junction-connected inter-neurons pervades the cortex, extending “in a boundless manner” [78].

Primary neurons including pyramidal cells also have gap junction connections, e.g., on horizontally arrayed basal dendrites up to 200 μm away from the cell body [79]. Pyramidal cell dendrites coupled by gap junctions (including axonal–axonal gap junctions) form a continuous lateral layer through the hippocampus [80]. The extent of gap junctions between inter-neurons and primary neurons, between neuronal axons, and between neurons and glia are as yet unknown.

Neurons and glia connected by gap junctions may be viewed as subsets of Golgi’s threaded-together reticulum, described as “syncytia” [75, 77], “hyper-neurons” [41, 81], or “dendritic webs” [82]. In neurocomputational network terms, dendritic webs are laterally connected input/integration layers.Footnote 19

Could gap junction networks extend, not only through cortex, but among all brain regions—a “brain-wide web”? Traub et al. [83, 84] suggest that bilateral cortical gamma synchrony is mediated by axonal–axonal gap junctions in thalamus, i.e., between descending cortical–thalamic neurons. However, bilateral gamma synchrony also depends on the corpus callosum [85]. Glial cells including oligodendrocytes have gap junction connections with neurons and other glia, extend great distances throughout the brain, and could enable brain-wide gap junction networks. Figure 4 shows six possible mechanisms for bi-hemispheric global gamma synchrony.

Schematic representation of possible mechanisms of bi-hemispheric cortical synchrony. Single neurons are used to illustrate dendritic webs composed of many gap-junction-connected neurons and glia. Top row (a–c) involve axonal–dendritic proposals, bottom row (d–f) involve gap junction explanations. a Axonal–dendritic feedback/reciprocal connections though corpus callosum [87], b axonal–dendritic feedback though thalamus [54], c thalamic pacemaker [7], d axonal–axonal gap junctions in thalamus [143], e dendritic web (e.g., including glia) through corpus callosum, f dendritic web (e.g., including glia) through thalamus and corpus callosum

Within a potential brain-wide web of gap-junction-connected neurons and glia, gamma-synchronized dendritic webs are particular subsets determined by gap junction dynamics, i.e., openings and closings. Gap junctions which are open act to electrically couple adjoining cells, inducing synchrony. Gap junctions which are closed do not couple and do not induce synchrony. Placement, openings, and closings of gap junctions are regulated by intra-neuronal calcium ions, cytoskeletal microtubules, and/or phosphorylation via G-protein metabotropic receptor activity [86, 87]. As various gap junctions open and close, form and disappear, the topology, location, and extent of synchronized dendritic web syncytia can change and move sideways through input/integration layers of axonal–dendritic networks throughout the brain.

The number of possible dendritic webs among billions of brain neurons and glia provides a near-infinite variety of topological syncytia, representational “Turing structures” which may be isomorphic with cognitive or conscious content [88]. Fleetingly shifting dendritic webs—spatiotemporal envelopes of dendritic synchrony—can correlate with conscious scenes and frames.

To illustrate, Figs. 5 and 6 continue the neurocomputational steps of Fig. 2, but with gap junctions which may open between dendrites. In step 3 (Fig. 5, left), a gap junction opens between dendrites of adjacent neurons in an inner layer, causing the two neuronal dendrites to become synchronized in a dendritic web (represented by vertical stripes). In steps 4 through 6, more gap junctions open as the dendritic web evolves and grows through specific topologies, e.g., becoming U-shaped in step 6. Thus, dendritic web synchrony can move “sideways” through integration layers of functioning neurocomputational networks.

Time steps 3 and 4 of network of toy neurons. In step 3, a gap junction has opened between dendrites of two neurons in the second layer, bringing dendritic synchrony (vertical stripes) for those two neurons comprising a dendritic web. In step 4 (right), additional gap junctions have opened and the dendritic web has grown and evolved, now involving six neurons. Axonal outputs from neurons within the synchronized web reflect collective integration (“conscious pilot”) and are marked by asterisks

Time steps 5 and 6 of network of toy neurons. In step 5 (left), more gap junctions have opened and the dendritic web has evolved into a “w-shaped” web of nine neurons. In step 6, the web has evolved and moved to a “u-shaped” web of 15 neurons. Axonal outputs from neurons within the synchronized web, reflecting collective integration (“conscious pilot”), are marked by asterisks

In Figs. 5 and 6, outputs from dendritic web (striped) neurons may be either 1 or 0. Outputs denoted in the figures by 1* or 0* are chosen by collective integration involving all neuronal members of a synchronized dendritic web. Metaphorically, these outputs are actions of the conscious pilot, a mobile integrator.

Such two-dimensional toy network webs may extrapolate to three-dimensional complex systems of neurons and glia and extend widely throughout cortex and brain. The step transitions correspond with gamma-synchronized frames, conscious moments. Spatially and temporally, a synchronized dendritic web moving through the brain is a suitable candidate for the NCC.Footnote 20

4 Agency, the “hard problem” and boundaries of consciousness

Volition, or agency, is the ability for consciousness to exert causal action, akin to free will.Footnote 21 Assuming dendritic web synchrony moves around the brain as the NCC, axonal–dendritic neurocomputation in any particular area continues regardless of whether gamma-synchronized dendritic webs are in the computational pathway. But if dendritic webs are present, axonal spike outputs in that pathway may be influenced by collective integration occurring in synchronized dendrites (* outputs in Figs. 5 and 6). Arguably, collective integration in dendritic/somatic webs can regulate axonal spike outputs more intelligently and efficiently than neurons acting individually. Whether more intelligent or not, spike firing outputs from axons of synchronized dendritic web neurons can differ from those same axons’ outputs when their neurons integrate and fire individually. Thus, dendritic web synchrony (and collective integration) can alter neurocomputational spike outputs, exert causal efficacy, and perform action. Dendritic webs are mobile integrators with agency, the ability to alter and control neurocomputational behavior like the conscious pilot assuming control from the auto-pilot.

Gamma-synchronized dendritic webs (or any NCC model) could provide the vehicle for an underlying process or condition which addresses the “hard problem,” i.e., manifests conscious experience.Footnote 22 A number of finer-scale underlying processes have been suggested.

Pockett [89], McFadden [90], and Libet [91] proposed that consciousness is inherent in the complex dynamical morphology and spatiotemporal properties of the brain’s electromagnetic field. The electromagnetic field from gamma synchrony EEG, the best NCC measure, is determined by dendritic webs.

Kasischke and Webb [92] suggested that consciousness may involve sub-neuronal functions “.... more refined on a higher temporal and smaller spatial scale.” Such faster smaller-scale activities could include intra-neuronal calcium ion gradients [34, 93], molecular reaction–diffusion patterns, actin sol-gel dynamics, glycolysis [94, 95], ribosomes [96], information processing in cytoskeletal microtubules [97], or some other mechanism. Some suggest consciousness depends on finer-scale processes in the realm of quantum physics [98, 99]. Penrose and Hameroff [82, 100–103] proposed that consciousness involves gamma-synchronized quantum computations in microtubules within dendritic webs.Footnote 23 They further suggested an approach to the “hard problem” of conscious experience, proposing that precursors or components of conscious experience, or “qualia”, were irreducible and fundamental features of reality (e.g., like spin, mass, or charge). Specific sets of qualia may be accessed and selected by the proposed quantum processes in microtubules [104, 105].

The concept of organized quantum processes in neurons and living cells has been discounted because of “decoherence,” the tendency for delicate low-energy quantum processes to be drowned out by the seemingly noisy “warm, wet, and noisy” biological environment. However, recent evidence has demonstrated quantum coherence in warm biology, mediated through non-polar regions in proteins [106]. The same type of non-polar regions in microtubules and other neuronal proteins may mediate quantum effects underlying consciousness and long-range gamma synchrony in the brain.

The boundaries of consciousness thus extend inward, to finer-scale processes inside neurons, e.g., to cytoskeletal microtubules, and further still, to quantum processes in non-polar regions inside microtubules and other biomolecules. The origins of consciousness may even extend all the way down to the fundamental level of the universe [104, 105].

Any fine-scale process mediating consciousness occurring on membrane surfaces or within neuronal interiors could be structurally unified and temporally synchronized by gap junctions and dendritic webs. To demonstrate, Fig. 7 shows a schematic close-up of two dendrites connected by a gap junction. Within each dendrite’s cytoplasmic interior, microtubules are connected by microtubule-associated proteins. Curved lines and interference patterns represent possible fine-scale processes underlying consciousness (e.g., electromagnetic fields, calcium ion gradients, molecular reaction–diffusion patterns, actin sol-gel dynamics, glycolysis, classical microtubule information processing, and/or microtubule quantum computation with entanglement and quantum coherence). These processes can extend through gap junctions and in principle throughout brain-wide dendritic webs. Thus, dendritic integration webs may unify (on a brain-wide basis) fine-scale processes comprising consciousness.

Schematic of possible underlying finer-scale processes related to consciousness extending through a gap junction to involve dendrites of adjacent neurons and in principle through an entire brain-wide dendritic web. Gap junction (connexin) proteins traverse both membranes; other membrane proteins (receptors/ion channels–smaller black cylinders) traverse one membrane. Microtubules connected by microtubule-associated proteins also shown. Possible processes illustrated by curved concentric interfering lines include electromagnetic fields, calcium ion gradients, molecular reaction–diffusion patterns, actin sol-gel dynamics, glycolysis, microtubule information processing and/or quantum computation, entanglement, etc.

5 Open questions and testable predictions

The conscious pilot NCC model proposes spatiotemporal envelopes of gamma synchrony (structurally defined by gap-junction-connected dendritic webs) move through the brain and mediate consciousness. As such, the model can be falsified by testable predictions in several categories.

Gap junction dynamics and dendritic web transitions

Long-range gamma synchrony and consciousness apparently move around the brain rapidly and abruptly, like critical phase transitions [20]. The fleeting synchronized spatiotemporal transitions and precise coherence on the order of tens of centimeters and tens of milliseconds are difficult to explain by axonal–dendritic networks. In principle, gap junction openings and closings can account for rapid sideways synchrony and dendritic web movements which correlate with consciousness. Do they?

Unity of consciousness and the brain-wide web

If consciousness correlates with dendritic web topologies, then at any one moment there should be only one dendritic web which will have exceeded some threshold for consciousness. For global synchrony (and metacognitive self-modes of consciousness), gap-junction-linked neurons and glia are required to span the brain, i.e., form a dendritic web syncytium extending frontal–posterior, right to left hemispheres, thalamocortical, limbic circuits, etc. (some possibilities are shown in Fig. 6). Using metabolic tracing, John et al. [81] showed evidence of extension of dye via gap junction channels extending through neurons and glia in both cortical hemispheres. Fukuda [78] has shown dendritic gap junction networks of inter-neurons extending “boundlessly” within cortex. Whether dendritic webs do indeed extend globally throughout the brain is empirically testable.

Blindsight

Gamma synchrony distinguishes conscious versus unconscious word perception [19] and (“conscious”) dreams from apparently dreamless sleep [8]. Another distinction between conscious and unconscious processing occurs in subjects with lesions of certain areas of visual cortex [107]. Blindsight patients have unconscious vision, e.g., reacting cognitively to objects they do not consciously “see.” Blindsight may occur in a region of brain permanently on auto-pilot, retaining axonal–dendritic neurocomputation but lacking dendritic sideways synchrony mediated by gap junctions.

Anesthesia

Under general anesthesia with anesthetic gases, consciousness is erased along with gamma synchrony EEG while slower EEG and evoked potential activity continue. Anesthetic gases act primarily on post-synaptic dendrites, specifically on a class of ∼70 membrane and cytoplasmic proteins (including connexin 36) [108, 109]. Do sideways synchrony and consciousness selectively cease under anesthesia while axonal–dendritic auto-pilot neurocomputation continues?

Agency

Dendritic web synchrony is proposed to affect axonal spike/firing outputs via collective integration among dendrites of the web’s multiple neurons. For each neuron, integration relates to spike/firing threshold—the voltage potential required at the axon initiation segment to trigger or fire an action potential spike. Naundorf et al. [110] found significant variability in spike threshold in cortical neurons in vivo compared to in vitro or simulated neurons. Are this variability and its consequent alteration of outputs dependent on collective integration among gap-junction-synchronized dendrites? Does it correlate with consciousness?

Zombie mice on auto-pilot

If specific proteins and genes are essential to consciousness, mice could be genetically engineered to lack these genes and their proteins. In principle, such mice would lack consciousness but retain non-conscious auto-pilot behavior. According to Koch [111], such “zombie” (auto-pilot) mice could be distinguished from normal, presumably conscious, mice by a reduced ability for complex spatial learning enabled by consciousness. Connexin 36 provides a test case. Using “knockout” gene technology, Hormuzdi et al. [112] generated mice lacking connexin 36, the primary dendritic–dendritic gap junction protein in cortical neurons. Connexin-36-deficient mice are viable with generally normal behavior but with markedly reduced gamma synchrony.Footnote 25 In cognitive testing [113], the mice showed relatively normal exploratory and anxiety-related responses. However, they were impaired in more complex sensorimotor capacities, learning, and memory (e.g., to complex spatial environments).Footnote 26 Could axonal–dendritic auto-pilot neurocomputation continue normally in connexin-36-deficient mice absent dendritic synchrony and the conscious pilot?

6 Summary—synchronized integration and the “conscious pilot”

The “conscious pilot” synchronized mobile integration model is a new candidate for the NCC. The conscious pilot refers to spatiotemporal envelopes of dendritic gamma synchrony (demarcated by gap-junction-defined “dendritic webs”) moving through the brain as vehicle for a conscious agent which can experience and control otherwise non-conscious (auto-pilot) cognitive functions.

We start with the assumption that cognitive brain functions including sensory processing, motor control of behavior, learning, memory, and attention all occur either with or without consciousness. Without consciousness, cognitive functions are scientifically explained by neurocomputation in neuronal networks, i.e., the brain’s axonal firings and synaptic transmissions acting like “bit states” and switches in computers. These non-conscious functions are deemed the “easy problems,” “zombie modes,” or “auto-pilot.”Footnote 27 They are not really easy but at least approachable through neurocomputation.

But consciousness—phenomenal awareness and conscious control—does not naturally ensue from neurocomputation. Science seeks to identify specific neuronal brain processes which underlie or correlate with consciousness—the NCC. The best measurable NCC is gamma synchrony EEG, coherent field potential oscillations in the range from 30 to 90 Hz. Gamma synchrony (along with consciousness, apparently) moves and evolves through various global distributions and brain regions.

But like consciousness, gamma synchrony does not ensue from neurocomputation in synaptic networks. Rather, gamma synchrony occurs via “sideways circuits”—neurons (and glia) inter-connected by electrical synapses called gap junctions which physically fuse and electrically couple neighboring cells. In particular, groups of neurons linked by dendritic–dendritic gap junctions form extensive gamma-synchronized syncytia or “dendritic webs” extending through brain regions.

Within neurocomputational networks, dendritic webs are laterally connected input/integration layers which can enable collective integration among synchronized neurons. As gap junctions open and close, spatiotemporal envelopes of synchronized neurons (dendritic webs) move and distribute rapidly around the brain as mobile integrators, vehicles for a conscious agent able to experience and control—tune into and take over—otherwise non-conscious auto-pilot neurocomputation. The conscious agent itself may be some finer-scale process extending within neuronal interiors through the dendritic web.Footnote 28

As a metaphor, an airplane flies on auto-pilot while the conscious pilot is sleeping or out of the cockpit engaged in other activities. If turbulence occurs, or an alarm sounds, the conscious pilot immediately returns to the cockpit and assumes conscious perception and control of the plane. When the problem resolves, the conscious pilot may again wander off as the auto-pilot computer takes over.

In the brain, the auto-pilot is neurocomputation mediated by axonal firings and synaptic transmissions in feed-forward and feedback neuronal networks. The conscious pilot is synchronized collective integration (dendritic webs) moving and evolving sideways through input/integration layers of the same neuronal network architecture.Footnote 29

Notes

Philosopher Ned Block [114] has distinguished access consciousness (“A-consciousness”) and phenomenal consciousness (“P-consciousness”). “A-consciousness” involves cognitive functions which are immediately available/accessible to consciousness but lack phenomenal experience. Block’s A-consciousness is thus seemingly equivalent to non-conscious “easy problems,” “zombie modes,” or “auto-pilot” and his “P-consciousness” comparable to the “hard problem,” “conscious modes,” or “conscious pilot.”

Neuronal-level origins of the EEG signal are discussed in the next section. Magnetoencephalography also reflects real-time brain activity from scalp or brain surfaces. In another type of approach, needle electrodes implanted into the brain generally record axonal action potential firings or spikes of individual neurons, not EEG which derives from local field potentials ensuing from post-synaptic dendritic activities of many neurons. Other approaches including functional brain imaging, e.g., functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), provide excellent spatial resolution of brain metabolic activity as measured by the BOLD signal related to blood oxygen levels. The BOLD signal may more closely reflect local field potentials and thus post-synaptic dendritic activity rather than axonal spikes [115, 116]. But fMRI and BOLD lack the temporal resolution of EEG.

For analysis, the complex signal is commonly broken down into activity in particular frequency bands: delta (less than 4 Hz), theta (4 to 7 Hz), alpha (8 to 12 Hz), beta (12 to 30 Hz), and gamma (30 to 90 Hz or higher).

In the early 1980s, brain synchrony as measured by EEG was proposed as a solution to the binding problem. Von der Malsburg [117] suggested synchronized oscillations among various brain regions bound together disparate content into unified conscious percepts. Consciousness seems to require binding, but does binding require consciousness (do non-conscious cognitive perceptions and actions involve binding)? If gamma synchrony invariably accompanies consciousness and implies binding, then non-conscious “auto-pilot” processes are likely to be unbound [17]. Thus mechanisms underlying gamma synchrony, binding, and consciousness are closely related [82, 118].

In the “conscious pilot” metaphor, this would be the conscious pilot in the cockpit, monitoring the view and instrument readings and manually controlling the plane.

As measured by fMRI metabolic activity, thalamocortical activity is reduced in both sleep and anesthesia compared to conscious subjects, prompting proposed equivalence between arousal and consciousness [27]. However, sensory-evoked potentials via thalamocortical arousal circuits are used to monitor spinal cord integrity during spinal surgeries under general anesthesia and thus occur without consciousness. Thalamocortical inputs in our daily life regarding, for example, the touch of shoes on our feet, are largely non-conscious. Purposeful behavior with arousal can occur without consciousness, e.g., when driving while daydreaming or in “zombie-like” patients going into, and emerging from, general anesthesia. “Going into” anesthesia is often accompanied by an excitatory “phase 2” stage, and waking from anesthesia may involve “emergence delirium,” both of which are arousal states without consciousness.

During anesthesia, increased local unsynchronized gamma frequency EEG activity (“gamma power”) is elicited and enhanced by evoked potentials) [119]. In Gray and Singer’s [5] seminal studies on cats, localized gamma synchrony was observed in visual cortex in response to visual stimuli under very low levels (less than half anesthetic dose) of ketamine, barbiturate, and inhaled anesthesia. Slower (sub-gamma) EEG, local unsynchronized gamma activity [30], and thalamocortical-evoked potentials continue or increase during anesthesia in the absence of long-range gamma synchrony and consciousness.

“Brainweb” of Varela et al. [120] is comparable, proposing that synchronized integration in various frequency bands in distributed brain regions comprise moments of conscious perception. The “Brainweb” assumes neuronal synchrony and connections occur via recurrent chemical synapses rather than the gap junction mechanisms discussed in this paper.

Computer worms are another possible metaphor for the conscious pilot, moving and replicating through computational networks.

Outnumbering neurons in the brain 10:1, glial cells (“glia”) support neuronal information processing but also have excitable membranes, receptors, calcium ion waves, cytoskeletal microtubules, synapses, and gap junctions and are involved in information processing [121, 122]. They are included in gap-junction-connected dendritic webs described in this paper.

Signals are conveyed by depolarization waves moving along membrane surfaces of dendrites, cell body, and axons, described by the Hodgkin–Huxley [123] equations which relate ionic currents across excitable membranes with voltage potential waves traveling along their surfaces. Depolarization waves in dendrites/cell body (graded, analog) differ from those in axons (all or none, digital).

Receptor proteins (ligand-gated ion channels) on dendrite and cell body membranes receive synaptic inputs from axons of other neurons via chemical neurotransmitters, inducing ion fluxes and graded/analog voltage patterns (excitatory and inhibitory post-synaptic potentials: “EPSPs” and “IPSPs”) which spatiotemporally integrate throughout the dendritic/cell body membrane to the AIS. When the integrated potential reaches threshold, an abrupt AIS membrane depolarization “fires” an action potential or spike which propagates rapidly and losslessly as a wave along the length of the axon. At the axon terminal, spikes induce release of neurotransmitters into synapses with downstream dendrites and cell bodies in axonal–dendritic networks of integrate-and-fire neurons.

Coherent spike volleys or axonal firing explosions must be preceded and caused by synchronized dendritic integration activity. Alkire et al. [27] argue generally for brain integration as the substrate of consciousness.

Many post-synaptic dendritic and somatic receptors are metabotropic, sending signals into dendritic interior cytoplasm and cytoskeleton rather than (or in addition to) changing membrane potentials. These cytoplasmic signals (chemical messengers, ion fluxes) activate enzymes, cause conformational signaling and ionic fluxes along actin filaments, and dephosphorylate microtubule-associated proteins which link and regulate cytoskeletal activity necessary for synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory [124–132]. Dendritic integration is also likely to include influence from dendrites from other neurons and glia via gap-junction-mediated synchrony (“collective integration”).

The subjective experience of the passage of time may be related to the frequency of conscious moments. When we are excited, perhaps our baseline rate of conscious moments goes up from 40 to 60 Hz, and, subjectively, time slows down [102].

In hippocampus, memory consolidation depends on “sharp wave–ripple complexes,” rapid 150- to 200-Hz oscillations (“ripples”) mediated by pyramidal cell gap junction connections, riding on slower theta/alpha frequency “sharp waves” [133].

The seemingly instantaneous depolarization of gap-junction-linked excitable membranes (i.e., despite the relative slowness of dendritic potential waves or spikelets) suggests that even gap junction coupling cannot fully account for the precise coherence of global brain gamma synchrony [56]. Gap junctions are necessary (though not sufficient) to account for precise global gamma synchrony.

Gap junctions are prominent in embryological formation of cortical circuits [134], then decline markedly in number as the brain matures. Accordingly, gap junctions are generally overlooked in relation to higher cognition and consciousness. But gap junctions do involve primary neurons. Venance et al. [135] showed gap junctions between interneurons and excitatory neurons in juvenile rat brain, and pyramidal cells (in hippocampal slices) share axonal–axonal gap junction coupling [136]. Gap junctions between primary hippocampal neurons play a role in high-frequency oscillations, e.g., 150 Hz [137]. Pruning and sparseness of gap junctions as the brain matures may be necessary for their utility. If each brain neuron were connected by open gap junctions to three or more different neurons, the entire brain would be one uninterrupted synchronized syncytium (Penrose, R—personal communication 1998).

Connexin-based gap junctions occur between dendrites of neighboring brain neurons, between dendrites and glia, glia and glia, axons and axons, and axons and dendrites—bypassing chemical synapses [138, 139]. Among ten or more different brain connexins, connexin 36 is the primary gap junction protein between brain neuronal dendrites.

Two examples, previously mentioned: conscious experience of smell occurs when gap-junction-mediated synchrony occurs among olfactory cortex dendrites [21–23]. When consciousness involves sexual feelings, dendritic gap junctions mediate gamma synchrony in brain regions involved in pleasure and reward [24]. Via gap junction openings and closings, gamma synchrony can move around the brain to mediate consciousness.

Free will implies an additional issue of determinism not addressed here. Some types of volitional agency may be localized, e.g., in right inferior parietal cortex [140].

Functionalists could argue such underlying process is unnecessary, in which case synchronized dendritic webs per se would solve the problems of conscious experience and control.

The Penrose–Hameroff model predicts dendritic webs of approximately 100,000 neurons for discrete conscious moments, or frames, occurring every 25 ms in gamma synchrony [101].

Unity of consciousness relates to binding, e.g., of disparate visual components such as shape, color, motion, and meaning into a unified visual percept. Unity also refers to one conscious self at home in the brain. Notable exceptions are “split-brain” patients whose corpus callosum—a bridge between right and left cortical hemispheres—has been transected (a lesion which also blocks global gamma synchrony). These patients appear to have two separate consciousnesses [141].

Presumably, other connexin (or pannexin) proteins compensate during development, so the mice may not be completely devoid of gap-junction-mediated synchrony nor consciousness.

Hosseinzadeh et al. [142] showed that normal rats given the gap-junction-blocking drug carbenoxolone also have impaired spatial learning.

Block’s “access consciousness” [114] would be included, in this non-conscious group, as phenomenal experience is lacking.

Functionalists may doubt the need or importance of a finer-scale process, in which case the dendritic web/mobile integrator solves the problem of conscious agent.

A benevolent computer worm moving through computational circuits is another appropriate analogy.

References

Chalmers, D.J.: The Conscious Mind—in Search of a Fundamental Theory. Oxford University Press, New York (1996)

Koch, C., Crick, F.: The zombie within. Nature 411, 893 (2001). doi:10.1038/35082161

Hodgson, D.: Making our own luck. Ratio 20, 278–292 (2007). doi:10.1111/j.1467-9329.2007.00365.x

Crick, F., Koch, C.: Towards a neurobiological theory of consciousness. Semin. Neurosci. 2, 263–275 (1990)

Gray, C.M., Singer, W.: Stimulus-specific neuronal oscillations in orientation columns of cat visual cortex. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86, 1698–1702 (1989). doi:10.1073/pnas.86.5.1698

Gray, C.M., Konig, P., Engel, A.K., Singer, W.: Oscillatory responses in cat visual cortex exhibit inter-columnar synchronization which reflects global stimulus properties. Nature 338, 334–337 (1989). doi:10.1038/338334a0

Ribary, U., Ioannides, A.A., Singh, K.D., Hasson, R., Bolton, J.P.R., Lado, F., Mogilner, A., Llinas, R.: Magnetic field topography of coherent thalamocortical 40-Hz oscillations in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 88, 11037–11041 (1991). doi:10.1073/pnas.88.24.11037

Llinas, R., Ribary, U.: Coherent 40-Hz oscillation characterizes dream state in humans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 90, 2078–2081 (1993). doi:10.1073/pnas.90.5.2078

Tiitinen, H., Sinkkonen, J., Reinikainen, K., Alho, K., Lavikainen, J., Naatanen, R.: Selective attention enhances the auditory 40-Hz transient response in humans. Nature 364, 59–60 (1993). doi:10.1038/364059a0

Desmedt, J.D., Tomberg, C.: Transient phase-locking of 40 Hz electrical oscillations in prefrontal and parietal human cortex reflects the process of conscious somatic perception. Neurosci. Lett. 168, 126–129 (1994). doi:10.1016/0304-3940(94)90432-4

Pantev, C.: Evoked and induced gamma band activity of the human cortex. Brain Topogr. 7, 321–330 (1995)

Tallon-Baudry, C., Bertrand, O., Delpuech, C., Pernier, J.: Stimulus specificity of phase-locked and non-phase-locked 40 Hz visual responses in human. J. Neurosci. 16, 4240–4249 (1996)

Tallon-Baudry, C., Bertrand, O., Delpuech, C., Pernier, J.: Oscillatory gamma band (30–70 Hz) activity induced by visual search task in human. J. Neurosci. 17, 722–734 (1997)

Miltner, W.H.R., Braun, C., Arnold, M., Witte, H., Taub, E.: Coherence of gamma-band EEG activity as a basis for associative learning. Nature 397, 434–436 (1999). doi:10.1038/17126

Mouchetant-Rostaing, Y., Giard, M.-H., Bentin, S., Aguera, P.A., Pernier, J.: Neurophysiological correlates of face gender processing in humans. Eur. J. Neurosci. 12, 303–310 (2000). doi:10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00888.x

Fries, P., Schroder, J.H., Roelfsema, P.R., Singer, W., Engel, A.K.: Oscillatory neuronal synchronization in primary visual cortex as a correlate of stimulus selection. J. Neurosci. 22(9), 3739–3754 (2002)

Mashour, G.A.: Consciousness unbound: toward a paradigm of general anesthesia. Anesthesiology 100, 428–433 (2004). doi:10.1097/00000542-200402000-00035

Garcia-Rill, E., Heister, D.S., Ye, M., Charlesworth, A., Hayar, A.: Electrical coupling: novel mechanism for sleep–wake control. Sleep 30(11), 1405–1414 (2007)

Melloni, L., Molina, C., Pena, M., Torres, D., Singer, W., Rodriguez, E.: Synchronization of neural activity across cortical areas correlates with conscious perception. J. Neurosci. 27(11), 2858–2865 (2007). doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4623-06.2007

Pockett, S., McPhail, A.V., Bold, G.E., Freeman, W.J.: Episodic global synchrony at all frequencies: implications for discrete/continuous consciousness debate. In: Toward a Science of Consciousness 2008, Abstract 206 (2008)

Christie, J.M., Bark, C., Hormuzdi, S.G., Helbig, I., Monyer, H., Westbrook, G.L.: Connexin 36 mediates spike synchrony in olfactory bulb glomeruli. Neuron 46(5), 761–772 (2005). doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.04.030

Christie, J.M., Westbrook, G.L.: Lateral excitation within the olfactory bulb. J. Neurosci. 26(8), 2269–2277 (2006). doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4791-05.2006

Rash, J.E., Davidson, K.G., Kamasawa, N., Yasumura, T., Kamasawa, M., Zhang, C., Michaels, R., Restrepo, D., Ottersen, O.P., Olson, C.O., Nagy, J.I.: Ultrastructural localization of connexins (Cx36, Cx43, Cx45), glutamate receptors and aquaporin-4 in rodent olfactory mucosa, olfactory nerve and olfactory bulb. J. Neurocytol. 34(3–5), 307–341 (2005). doi:10.1007/s11068-005-8360-2

Lassen, M.B., Brown, J.E., Stobbs, S.H., Gunderson, S.H., Maes, L., Valenzuela, C.F., Ray, A.P., Henriksen, S.J., Steffensen, S.C.: Brain stimulation reward is integrated by a network of electrically coupled GABA neurons. Brain Res. 1156, 46–58 (2007). doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2007.04.053

Baars, B.J.: A Cognitive Theory of Consciousness. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (1988)

Fahrenfort, J.J., Scholte, H.S., Lamme, V.A.: The spatiotemporal profile of cortical processing leading up to visual perception. J. Vis. 8(1), 12.1–12 (2008)

Alkire, M.T., Hudetz, A.G., Tononi, G.: Consciousness and anesthesia. Science 7, 876–880 (2008). doi:10.1126/science.1149213

Vincent, J.L., Patel, G.H., Fox, M.D., Snyder, A.Z., Baker, J.T., Van Essen, D.C., Zempel, J.M., Snyder, L.H., Corbetta, M., Raichle, M.E.: Intrinsic functional architecture in the anaesthetized monkey brain. Nature 447, 83–86 (2007). doi:10.1038/nature05758

John, E.R., Prichep, L.S.: The anesthetic cascade. A theory of how anesthesia suppresses consciousness. Anesthesiology 102, 447–471 (2005). doi:10.1097/00000542-200502000-00030

Imas, O.A., Ropella, K.M., Ward, B.D., Wood, J.D., Hudetz, A.G.: Volatile anesthetics disrupt frontal–posterior recurrent information transfer at gamma frequencies in rat. Neurosci. Lett. 387(3), 145–150 (2005). doi:10.1016/j.neulet.2005.06.018

Lutz, A., Greischar, L.L., Rawlings, N.B., Ricard, M., Davidson, R.J.: Long-term meditators self-induce high-amplitude gamma synchrony during mental practice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101(46), 16369–16373 (2004). doi:10.1073/pnas.0407401101

Schoffelen, J.M., Oostenveld, R., Fries, P.: Neuronal coherence as a mechanism of effective corticospinal interaction. Science 308(5718), 111–113 (2005). doi:10.1126/science.1107027

Ramón y Cajal, S.: Histologie du Système Nerveux de L’homme et des Vertébrés (1909)

Koch, C.: The Quest for Consciousness: A Neurobiological Approach. Roberts and Company, Englewood (2004)

Crick, F.C., Koch, C.: A framework for consciousness. Nat. Neurosci. 6, 119–126 (2001). doi:10.1038/nn0203-119

McCulloch, W., Pitts, W.: A logical calculus of the ideas immanent in nervous activity. Bull. Math. Biophys. 5, 115–133 (1943). doi:10.1007/BF02478259

Rosenblatt, F.: Principles of Neurodynamics. Spartan Books, New York (1962)

Malach, R.: The measurement problem in human consciousness research. Behav. Brain Sci. 30, 481–499 (2007). doi:10.1017/S0140525X0700297X

Pribram, K.H.: Brain and Perception. Lawrence Erlbaum, Upper Saddle River (1991)

Eccles, J.C.: Evolution of consciousness. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89, 7320–7324 (1992). doi:10.1073/pnas.89.16.7320

Woolf, N.J., Hameroff, S.R.: A quantum approach to visual consciousness. Trends Cogn. Sci. 5, 472–478 (2001). doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(00)01774-5

Shepherd, G.M.: The dendritic spine: a multifunctional integrative unit. J. Neurophysiol. 75, 2197–2210 (1996)

Sourdet, V., Debanne, D.: The role of dendritic filtering in associative long-term synaptic plasticity. Learn. Mem. 6(5), 422–447 (1999). doi:10.1101/lm.6.5.422

Poirazi, P.F., Mel, B.W.: Impact of active dendrites and structural plasticity on the memory capacity of neural tissue. Neuron 29(3), 779–796 (2001). doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00252-5

Woolf, N.J.: A structural basis for memory storage in mammals. Prog. Neurobiol. 55, 59–77 (1998). doi:10.1016/S0301-0082(97)00094-4

Woolf, N.J., Zinnerman, M.D., Johnson, G.V.W.: Hippocampal microtubule-associated protein-2 alterations with contextual memory. Brain Res. 821, 241–249 (1999). doi:10.1016/S0006-8993(99)01064-1

James, W.: The Principles of Psychology, vol. 1. Holt, New York (1890)

Whitehead, A.N.: Process and Reality. Macmillan, New York (1929)

Whitehead, A.N.: Adventure of Ideas. Macmillan, London (1933)

Stroud, J.M.: The fine structure of psychological time. In: Quastler, H. (ed.) Information Theory in Psychology, pp. 174–205. Free Press, Glencoe (1956)

VanRullen, R., Koch, C.: Is perception discrete or continuous? Trends Cogn. Sci. 7(5), 207–213 (2003). doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(03)00095-0

Freeman, W.J.: A cinematographic hypothesis of cortical dynamics in perception. Int. J. Psychophysiol. 60(2), 149–161 (2006). doi:10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2005.12.009

Joliot, M., Ribary, U., Llinas, R.: Human oscillatory brain activity near 40 Hz coexists with cognitive temporal binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 91(24), 11748–11751 (1994). doi:10.1073/pnas.91.24.11748

Shadlen, M.N., Movshon, J.A.: Synchrony unbound: a critical evaluation of the temporal binding hypothesis. Neuron 24, 67–77 (1999). doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(00)80822-3

Buszaki, G.: Rhythms of the Brain. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2006)

Freeman, W.J., Vitiello, G.: Nonlinear brain dynamics as macroscopic many-body field dynamics. Phys. Life Rev. 3, 93–118 (2006). doi:10.1016/j.plrev.2006.02.001

Herve, J.C.: The connexins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1711, 97–98 (2004)

VanRullen, R., Thorpe, S.J.: The time course of visual processing: from early perception to decision making. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 13(4), 454–461 (2001). doi:10.1162/08989290152001880

Rouach, N., Avignone, E., Meme, W., Koulakoff, A., Venance, L., Blomstrand, F., Giaume, C.: Gap junctions and connexin expression in the normal and pathological central nervous system. Biol. Cell 94(7–8), 457–475 (2002). doi:10.1016/S0248-4900(02)00016-3

Bruzzone, R., Hormuzdi, S.G., Barbe, M.T., Herb, A., Monyer, H.: Pannexins, a family of gap junction proteins expressed in brain. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100(23), 13644–13649 (2003). doi:10.1073/pnas.2233464100

Kandel, E.R., Schwartz, J.S., Jessell, T.M.: Principles of Neural Science, 4th edn. New York, McGraw-Hill (2000)

Zsiros, V., Aradi, I., Maccaferri, G.: Propagation of postsynaptic currents and potentials via gap junctions in GABAergic networks of the rat hippocampus. J. Physiol. 578(Pt 2), 527–544 (2007). doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2006.123463

Dermietzel, R.: Gap junction wiring: a ‘new’ principle in cell-to-cell communication in the nervous system? Brains Res. Rev. 26(2–3), 176–183 (1998). doi:10.1016/S0165-0173(97)00031-3

Draguhn, A., Traub, R.D., Schmitz, D., Jeffreys, J.G.: Electrical coupling underlies high-frequency oscillations in the hippocampus in vitro. Nature 394(6689), 189–192 (1998). doi:10.1038/28184

Hormuzdi, S.G., Filippov, M.A., Mitropoulou, G., Monyer, H., Bruzzone, R.: Electrical synapses: a dynamic signaling system that shapes the activity of neuronal networks. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1662(1–2), 113–137 (2004). doi:10.1016/j.bbamem.2003.10.023

Bennett, M.V., Zukin, R.S.: Electrical coupling and neuronal synchronization in the Mammalian brain. Neuron 41(4), 495–511 (2004). doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(04)00043-1

LeBeau, F.E., Traub, R.D., Monyer, H., Whittington, M.A., Buhl, E.H.: The role of electrical signaling via gap junctions in the generation of fast network oscillations. Brain Res. Bull. 62(1), 3–13 (2003). doi:10.1016/j.brainresbull.2003.07.004

Friedmand, D., Strowbridge, B.W.: Both electrical and chemical synapses mediate fast network oscillations in the olfactory bulb. J. Neurophysiol. 89(5), 2601–2610 (2003). doi:10.1152/jn.00887.2002

Buhl, D.L., Harris, K.D., Hormuzdi, S.G., Monyer, H., Buzsaki, G.: Selective impairment of hippocampal gamma oscillations in connexin-36 knock-out mouse in vivo. J. Neurosci. 23(3), 1013–1018 (2003)

Perez Velazquez, J.L., Carlen, P.L.: Gap junctions, synchrony and seizures. Trends Neurosci. 23(2), 68–74 (2000). doi:10.1016/S0166-2236(99)01497-6

Rozental, R., Giaume, C., Spray, D.C.: Gap junctions in the nervous system. Brains Res. Rev. 32(1), 11–15 (2000). doi:10.1016/S0165-0173(99)00095-8

Galarreta, M., Hestrin, S.: A network of fast-spiking cells in the neocortex connected by electrical synapses. Nature 402, 72–75 (1999). doi:10.1038/47029

Galarreta, M., Hestrin, S.: Electrical synapses between GABA-releasing interneurons. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2(6), 425–433 (2001). doi:10.1038/35077566

Gibson, J.R., Beierlein, M., Connors, B.W.: Two networks of electrically coupled inhibitory neurons in neocortex. Nature 402, 75–79 (1999). doi:10.1038/47035

Amitai, Y., Gibson, J.R., Beierlein, M., Patrick, S.L., Ho, A.M., Connors, B.W., Golomb, D.: The spatial dimensions of electrically coupled networks of interneurons in the neocortex. J. Neurosci. 22(10), 4142–4152 (2002)

Tamas, G., Buhl, E.H., Lorincz, A., Somogyi, P.: Proximally targeted GABAergic synapses and gap junctions synchronize cortical interneurons. Nat. Neurosci. 3, 366–371 (2000). doi:10.1038/73936

Fukuda, T., Kosaka, T.: Gap junctions linking the dendritic network of GABAergic interneurons in the hippocampus. J. Neurosci. 20(4), 1519–1528 (2000)

Fukuda, T.: Structural organization of the gap junction network in the cerebral cortex. Neuroscientist 13(3), 199–207 (2007). doi:10.1177/1073858406296760

Mercer, A., Bannister, A.P., Thomson, A.M.: Electrical coupling between pyramidal cells in adult cortical regions. Brain Cell Biol. 35(1), 13–27 (2006). doi:10.1007/s11068-006-9005-9

Bennett, M.V.L., Pereda, A.: Pyramid power: principal cells of the hippocampus unite! Brain Cell Biol. 35(1), 5–11 (2006). doi:10.1007/s11068-006-9004-x

John, E.R., Tang, Y., Brill, A.B., Young, R., Ono, K.: Double layered metabolic maps of memory. Science 233, 1167–1175 (1986). doi:10.1126/science.3488590

Hameroff, S.: The brain is both neurocomputer and quantum computer. Cogn. Sci. 31, 1035–1045 (2007)

Traub, R.D., Whittington, M.A., Stanford, I.M., Jefferys, J.G.: A mechanism for generation of long-range synchronous fast oscillations in the cortex. Nature 383(6601), 621–624 (1996). doi:10.1038/383621a0

Traub, R.D., Draguhn, A., Whittington, M.A., Baldeweg, T., Bibbig, A., Buhl, E.H., Schmitz, D.: Axonal gap junctions between principal neurons: a novel source of network oscillations, and perhaps epileptogenesis. Rev. Neurosci. 13(1), 1–30 (2002)

Engel, A.K., Konig, P., Kreiter, A.K., Singer, W.: Interhemispheric synchronization of oscillatory neuronal responses in cat visual cortex. Science 252, 1177–1179 (1991). doi:10.1126/science.252.5009.1177

Shaw, R.M., Fay, A.J., Puthenveedu, M.A., von Zastrow, M., Jan, Y.N., Jan, L.Y.: Microtubule plus-end-tracking proteins target gap junctions directly from the cell interior to adherens junctions. Cell 128(3), 547–560 (2007). doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.12.037

Hatton, G.I.: Synaptic modulation of neuronal coupling. Cell Biol. Int. 22, 765–780 (1998). doi:10.1006/cbir.1998.0386

Steyn-Ross, M.L., Steyn-Ross, D.A., Wilson, M.T., Sleigh, J.W.: Gap junctions mediate large-scale Turing structures in a mean-field cortex driven by subcortical noise. Phys. Rev. E Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 76(1 Pt 1), 011916 (2007)

Pockett, S.: The Nature of Consciousness: A Hypothesis. Iuniverse, New York (2000)

McFadden, J.: The conscious electromagnetic field theory: the hard problem made easy. J. Conscious. Stud. 9(8), 45–60 (2002)

Libet, B.: Mind Time: The Temporal Factor in Consciousness. Cambridge, Harvard University Press (2004)

Kasischke, K.A., Webb, W.W.: Producing neuronal energy. Science 306, 411 (2004)

Freitas da Rocha, A., Pereira, A., Jr., Bezerra Coutinho, F.A.: N-methyl-d-aspartate channel and consciousness: from signal coincidence detection to quantum computing. Prog. Neurobiol. 64(6), 555–573 (2001). doi:10.1016/S0301-0082(00)00069-1

Wu, K., Aoki, A., Elste, A., Rogalski-Wilk, P., Siekevitz, P.: The synthesis of ATP by glycolytic enzymes in the postsynaptic density and the effect of endogenously generated nitric oxide. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94, 13273 (1997). doi:10.1073/pnas.94.24.13273

Siekevitz, P.: Producing neuronal energy. Science 306, 410–411 (2004). doi:10.1126/science.306.5695.410

O’Connell, C., O’Malley, A., Regan, C.M.: Transient, learning-induced ultrastructural change in spatially-clustered dentate granule cells of the adult rat hippocampus. Neuroscience 76(1), 55–62 (1997). doi:10.1016/S0306-4522(96)00387-9

Hameroff, S., Watt, R.C.: Information processing in microtubules. J. Theor. Biol. 98, 549–561 (1982). doi:10.1016/0022-5193(82)90137-0

Schrodinger, E.: Die gegenwarten situation in der quantenmechanik. Naturwissenschaften 23, 807–812, 823–828, 844–849 (1935) (Translation by Trimmer, J.T.: (1980) in Proc. Amer. Phil. Soc. 124, 323–338) In: Wheeler, J.A., Zurek, W.H. (eds.) Quantum Theory and Measurement. Princeton University Press, Princeton (1983)

Stapp, H.P.: Mind, matter and quantum mechanics. Springer, Berlin (1993)

Penrose, R., Hameroff, S.R.: Gaps, what gaps? Reply to Grush and Churchland. J. Conscious. Stud. 2(2), 99–112 (1995)

Hameroff, S.R., Penrose, R.: Orchestrated reduction of quantum coherence in brain microtubules: a model for consciousness. In: Hameroff, S.R., Kaszniak, A.W., Scott, A.C. (eds.) Toward a Science of Consciousness The First Tucson Discussions and Debates, pp. 507–540. MIT Press, Cambridge. Also published in Mathematics and Computers in Simulation, vol. 40, pp. 453–480 (1996). http://www.consciousness.arizona.edu/hameroff/or.html

Hameroff, S.: Quantum computation in brain microtubules? The Penrose Hameroff “Orch OR” model of consciousness. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. Ser. A 356, 1869–1896 (1998). http://www.consciousness.arizona.edu/hameroff/royal2.html

Hameroff, S.: Consciousness, neurobiology and quantum mechanics: the case for a connection. In: Tuszynski, J. (ed.) The Emerging Physics of Consciousness. Springer, Heidelberg (2006)

Hameroff, S.R., Penrose, R.: Conscious events as orchestrated space time selections. J. Conscious. Stud. 3(1), 36–53 (1996). http://www.u.arizona.edu/hameroff/penrose2

Hameroff, S., Powell, J.: The conscious connection: a psycho-physical bridge between brain and pan-experiential quantum geometry. In: Skrbina, D. (ed.) Mind that Abides: Panpsychism in the New Millennium. Benjamins, Amsterdam pp 109–127 (2009)

Engel, G.S., Calhoun, T.R., Read, E.L., Ahn, T.-K., Mancal, T., Cheng, Y.-C., Blankenship, R.E., Fleming, G.R.: Evidence for wavelike energy transfer through quantum coherence in photosynthetic systems. Nature 446, 782–786 (2007). doi:10.1038/nature05678

Stoerig, P., Cowey, A.: Blindsight. Curr. Biol. 17(19), R822–R824 (2007). doi:10.1016/j.cub.2007.07.016

Xi, J., Liu, R., Asbury, G.R., Eckenhoff, M.F., Eckenhoff, R.G.: Inhalational anesthetic-binding proteins in rat neuronal membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 279(19), 19628–19633 (2004). doi:10.1074/jbc.M313864200

Wentlandt, K., Samoilova, M., Carlen, P.L., El Beheiry, H.: General anesthetics inhibit gap junction communication in cultured organotypic hippocampal slices. Anesth. Analg. 102(6), 1692–1698 (2006). doi:10.1213/01.ane.0000202472.41103.78

Naundorf, B., Wolf, F., Volgushev, M.: Unique features of action potential initiation in cortical neurons. Nature 440(7087), 1060–1063 (2006). doi:10.1038/nature04610

Koch, C.: Double dissociation between attention and consciousness. In: Toward a Science of Consciousness 2008, Abstract 143 (2008)

Hormuzdi, S.G., Pais, I., LeBeau, F.E., Towers, S.K., Rozov, A., Buhl, E.H., Whittington, M.A., Monyer, H.: Impaired electrical signaling disrupts gamma frequency oscillations in connexin 36-deficient mice. Neuron 31(3), 487–495 (2001). doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00387-7

Frisch, C., De Souza-Silva, M.A., Sohl, G., Guldenagel, M., Willecke, K., Huston, J.P., Dere, E.: Stimulus complexity dependent memory impairment and changes in motor performance after deletion of the neuronal gap junction protein connexin 36 in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 157(1), 177–185 (2005). doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2004.06.023

Block, N.: Consciousness, accessibility, and the mesh between psychology and neuroscience. Behav. Brain Sci. 30(5–6), 481–499 (2007)

Logothetis, N.K.: The neural basis of the blood-oxygen-level-dependent functional magnetic resonance imaging signal. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 357, 1003–1037 (2002). doi:10.1098/rstb.2002.1114

Viswanathan, A., Freeman, R.D.: Neurometabolic coupling in cerebral cortex reflects synaptic more than spiking activity. Nat. Neurosci. 10, 1308–1312 (2007). doi:10.1038/nn1977

Von der Malsburg, C.: The correlation theory of brain function. MPI biophysical chemistry, internal reports 81-2 (1981). In: Domany, E., van Hemmen, J.L., Schulten, K. (eds.) Reprinted in Models of Neural Networks II. Berlin, Springer (1994)

Zeki, S.: The disunity of consciousness. Trends Cogn. Sci. 7, 214–218 (2003). doi:10.1016/S1364-6613(03)00081-0

Imas, O.A., Ropella, K.M., Ward, B.D., Wood, J.D., Hudetz, A.G.: Volatile anesthetics enhance flash-induced gamma oscillations in rat visual cortex. Anesthesiology 102(5), 937–947 (2005). doi:10.1097/00000542-200505000-00012

Varela, F., Lachaux, J.P., Rodriguez, E., Martinerie, J.: The brainweb: phase synchronization and large-scale integration. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2, 229–239 (2001). doi:10.1038/35067550

Perea, G., Araque, A.: Glial calcium signaling and neuron-glia communication. Cell Calcium 38(3–4), 375–382 (2005). doi:10.1016/j.ceca.2005.06.015

Deitmer, J.W., McCarthy, K.D., Scemes, E., Giaume, C.: Information processing and transmission in glia: calcium signaling and transmitter release. Glia 54(7), 639–641 (2006). doi:10.1002/glia.20428

Hodgkin, A., Huxley, A.: A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J. Physiol. 117, 500–544 (1952)

Theurkauf, W.E., Vallee, R.B.: Extensive cAMP-dependent and cAMP independent phosphorylation of microtubule-associated protein 2. J. Biol. Chem. 258, 7883–7886 (1983)

Aoki, C., Siekevitz, P.: Plasticity in brain development. Sci. Am. 259, 56–64 (1988)

Johnson, G.V.W., Jope, R.S.: The role of microtubule-associated protein 2 (MAP-2) in neuronal growth, plasticity, and degeneration. J. Neurosci. Res. 33, 505–512 (1992). doi:10.1002/jnr.490330402

Halpain, S., Greengard, P.: Activation of NMDA receptors induces rapid dephosphorylation of the cytoskeletal protein MAP2. Neuron 5, 237–246 (1990). doi:10.1016/0896-6273(90)90161-8

Van der Zee, E.A., Douma, B.R., Bohus, B., Luiten, P.G.: Passive avoidance training induces enhanced levels of immunoreactivity for muscarinic acetylcholine receptor and coexpressed PKC gamma and MAP-2 in rat cortical neurons. Cereb. Cortex 4(4), 376–390 (1994). doi:10.1093/cercor/4.4.376

Whatley, V.J., Harris, R.A.: The cytoskeleton and neurotransmitter receptors. Int. Rev. Neurobiol. 39, 113–143 (1996). doi:10.1016/S0074-7742(08)60665-0

Fischer, M., Kaech, S., Wagner, U., Brinkhaus, H., Matus, A.: Glutamate receptors regulate actin-based plasticity in dendritic spines. Nat. Neurosci. 3(9), 887–894 (2000). doi:10.1038/78791

Matus, A.: Actin-based plasticity in dendritic spines. Science 290, 754–758 (2000). doi:10.1126/science.290.5492.754

Khuchua, Z., Wozniak, D.F., Bardgett, M.E., Yue, Z., McDonald, M., Boero, J., Hartman, R.E., Sims, H., Strauss, A.W.: Deletion of the N-terminus of murine map2 by gene targeting disrupts hippocampal ca1 neuron architecture and alters contextual memory. Neuroscience 119(1), 101–111 (2003). doi:10.1016/S0306-4522(03)00094-0

Maier, N., Nimmrich, V., Draguhn, A.: Cellular and network mechanisms underlying spontaneous sharp wave-ripple complexes in mouse hippocampal slices. J. Physiol. 550(Pt 3), 873–887 (2003). doi:10.1113/jphysiol.2003.044602

Bittman, K., Becker, D.L., Cicirata, F., Parnavelas, J.G.: Connexin expression in homotypic and heterotypic cell coupling in the developing cerebral cortex. J. Comp. Neurol. 443(3), 201–212 (2002). doi:10.1002/cne.2121

Venance, L., Rozov, A., Blatow, M., Burnashev, N., Feldmeyer, D., Monyer, H.: Connexin expression in electrically coupled postnatal rat brain neurons. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 97(18), 10260–10265 (2000). doi:10.1073/pnas.160037097

Traub, R.D., Kopell, N., Bibbig, A., Buhl, E.H., LeBeau, F.E., Whittington, M.A.: Gap junctions between interneuron dendrites can enhance synchrony of gamma oscillations in distributed networks. J. Neurosci. 21(23), 9478–9486 (2001)

Schmitz, D., Schuchmann, S., Fisahn, A., Draguhn, A., Buhl, E.H., Petrasch-Parwez, E., Dermietzel, R., Heinemann, U., Traub, R.D.: Axo-axonal coupling. a novel mechanism for ultrafast neuronal communication. Neuron 31(5), 831–840 (2001). doi:10.1016/S0896-6273(01)00410-X

Froes, M.M., Menezes, J.R.: Coupled heterocellular arrays in the brain. Neurochem. Int. 41(5), 367–375 (2002). doi:10.1016/S0197-0186(02)00016-5

Bezzi, P., Volterra, A.: A neuron-glia signalling network in the active brain. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 11(3), 387–394 (2001). doi:10.1016/S0959-4388(00)00223-3

Goldberg, I., Ullman, S., Malach, R.: Neuronal correlates of “free will” are associated with regional specialization in the human intrinsic/default network. Conscious. Cogn. 17(3), 587–601 (2008). doi:10.1016/j.concog.2007.10.003

Gazzaniga, M.S.: Forty-five years of split-brain research and still going strong. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 6(8), 653–659 (2005). doi:10.1038/nrn1723

Hosseinzadeh, H., Asl, M.N., Parvardeh, S., Tagi Mansouri, S.M.: The effects of carbenoxolone on spatial learning in the Morris water maze task in rats. Med. Sci. Monit. 11(3), BR88–BR94 (2005)

Froes, M.M., Correia, A.H., Garcia-Abreu, J., Spray, D.C., Campos de Carvalho, A.C., Neto, M.V.: Gap-junctional coupling between neurons and astrocytes in primary central nervous system cultures. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96(13), 7541–7546 (1999). doi:10.1073/pnas.96.13.7541

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Dave Cantrell for artwork and Marjan Macphee for assistance in manuscript preparation.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Hameroff, S. The “conscious pilot”—dendritic synchrony moves through the brain to mediate consciousness. J Biol Phys 36, 71–93 (2010). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10867-009-9148-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10867-009-9148-x