Abstract

Species confined to temporally stable habitats are usually susceptible to habitat fragmentation, as living in long-lasting habitats is predicted to constrain evolution of dispersal ability. In Europe, saproxylic invertebrates associated with tree hollows are currently threatened due to the severe fragmentation of their habitat, but data on the population genetic consequences of such habitat decline are still scarce. By employing AFLP markers, we compared the spatial genetic structure of two ecologically and taxonomically related beetle species, Osmoderma barnabita and Protaetia marmorata (Cetoniidae). Both species are exclusively associated with tree hollows, but O. barnabita has a more restricted host preferences compared to P. marmorata. Analyses of spatial autocorrelation showed, in line with the predicted low dispersal potential of these saproxylic beetles, that both species are characterized by a strong kinship structure, which was more pronounced in the specialist O. barnabita than in the generalist P. marmorata. Individuals of both species sampled within single trees showed high relatedness (≈0.50 in O. barnabita and ≈0.15 in P. marmorata). Interestingly, groups of pheromone-emitting O. barnabita males sampled on the same tree trunk were found to be full brothers. Whether this result can be explained by kin selection to increase attraction of conspecific females for mating or by severe inbreeding of beetles within individual tree hollows needs further study. Although our studied populations were significantly inbred, our results suggest that the dispersal ability of Osmoderma beetles may be one order of magnitude greater than suggested by previous dispersal studies and acceptable levels of habitat fragmentation for metapopulation survival may be bigger than previously thought.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Habitat destruction and fragmentation is predicted to cause severe genetic consequences for many species, as the ability to disperse between habitat patches will be constrained (Fahrig 2003). A reduced rate of dispersals between patches will presumably increase genetic differentiation between populations, and genetic drift will decrease genetic variation within populations. As a result, remnant local populations experiencing increased levels of inbreeding will have a lower capacity to adapt to a changing environment, which subsequently increases the risk of extinction (Frankham 2005). It has been hypothesized that the evolution of dispersal behaviour could be related to habitat longevity and environmental predictability (e.g. Travis and Dytham 1999). Species occupying habitats with low temporal but high spatial variability are predicted to be more susceptible to habitat fragmentation than species confined to more ephemeral habitats. Thus, living in habitats with low turnover rate will constrain evolution of dispersal capacity (Roff 1975; Levin et al. 1984; Nilsson and Baranowski 1997). In contrast, living in habitats, which are abundant and uniformly distributed in the landscape should favour evolution of dispersal towards higher rates (Hastings 1983; Holt 1985; Travis and Dytham 1999). However, theoretical models have also suggested that at least some level of dispersal would be advantageous under all regimes of spatial and temporal heterogeneity (Travis and Dytham 1998).

In Europe, hollows in large trees represent an extremely stable habitat, which could remain suitable for the specialised invertebrate fauna for hundreds of years (Ranius et al. 2009). Such hollow trees are therefore expected to have many species well adapted to this kind of stable habitat and therefore demonstrating low dispersal abilities (Nilsson and Baranowski 1997). However, individual tree hollows can differ significantly in several characteristics, such as the wood mould volume, the size and direction of the entrance hole (Ranius and Nilsson 1997), or tree species identity (Oleksa et al. 2006, 2007). In general, large cavities with a stable microclimate developed only in the largest trees are the most rare resource (Sedgeley 2001). Such cavities with large amounts of wood mould harbour a specialized invertebrate fauna (Dajoz 2000). Due to the felling of many over-mature trees in Europe during the last centuries, this habitat has decreased severely, which has rendered numerous insect species associated with large-volume hollows among the most threatened species (Speight 1989). However, habitat fragmentation should have a more detrimental effect on specialists confined to few tree species compared to generalists confined to a larger number of tree species because the dispersal capacity should be lower for specialists than for generalists of hollow-living species, and the distribution of habitat patches of sufficiently high quality in the landscape should be less predictable for the specialists compared to the generalists (Futuyma and Moreno 1988; Brouat et al. 2003; Zayed et al. 2005).

The hypothesis that specialists are more vulnerable to increased isolation than generalists can be addressed by comparing the genetic population structure between closely related species with overlapping distributions but different niche breadth, thus controlling for both phylogenetic and geographic effects. In this study, we investigated the genetic population structure of two species of scarab beetles (subfamily Cetoniinae), which are exclusively confined to tree hollows, where the larvae feed on wood mould or decaying wood. The hermit beetle, Osmoderma barnabita, has restricted preference for certain tree species in the area under study (especially lime Tilia cordata; Oleksa et al. 2007), whereas the marbled rose chafer, Protaetia marmorata, has a broader ecological niche and shows no preferences for tree species (Oleksa et al. 2006). According to the theoretical models of dispersal (reviewed by Futuyma and Moreno 1988), we would expect lower dispersal rates and dispersal distances in the more specialised O. barnabita. Indeed, previous dispersal studies of the sister species O. eremita, including mark-release-recapture (Ranius and Hedin 2001) and radio-tracking (Hedin et al. 2008; Svensson et al. 2011) have revealed low dispersal rates and ranges in that species, with most recorded dispersals being shorter than 100 m. Whereas the use of a pheromone-based trapping system has greatly aided the analysis of dispersal behaviour and population estimates in the European hermit beetles (Larsson and Svensson 2009; Svensson et al. 2011), no pheromone has yet been identified for P. marmorata, and no estimates of its dispersal capacity are available. A major constraint in using mark-release-recapture, pheromone trapping, or telemetry to study dispersal is that long-range dispersals are extremely difficult to detect, which may skew the data toward lower dispersal distances. An alternative approach to study dispersal would be to use molecular markers to characterize spatial genetic structure of populations of a species and indirectly quantify dispersal and gene flow between such populations to evaluate its vulnerability to habitat fragmentation.

In this study we used AFLP (Amplified Fragment Length Polymorphism) markers to test whether the population genetic structure of the species with a narrow niche breadth (O. barnabita) would be more affected by isolation by distance than the species with a broader niche breadth (P. marmorata). We predicted that: (1) the spatial genetic structure should be stronger for O. barnabita than for P. marmorata; (2) the presumably lower dispersal capacity in O. barnabita would result in higher level of inbreeding compared to the presumably more mobile P. marmorata. We hoped that the results of our study could be used when designing efficient conservation strategies for these species.

Materials and methods

Studied organisms

Hermit beetles of the genus Osmoderma LePeletier de Saint-Fargeau & Serville, 1828 are known for their fruity odour, which is released in large amounts by males (Larsson et al. 2003; Svensson et al. 2009). During the last decade, European hermit beetles have emerged as a major model species for ecological research on insects associated with hollow deciduous trees in Europe (Ranius et al. 2005). As an indicator species of the species-rich fauna of saproxylic insects, Osmoderma eremita is listed as a priority species in Annex IV of the EU’s Habitat Directive (Anonymous 1992). Historically, there has been considerable confusion regarding the taxonomic status of Osmoderma populations in Europe, with up to five distinct species or subspecies distinguished within the O. eremita species group based on subtle geographical variation in morphology (reviewed in Audisio et al. 2007). Two highly supported clades could be distinguished, the western (including O. eremita s.str (Scopoli, 1763). and O. cristinae Sparacio, 1994), distributed from Sicily and northern Spain to Sweden, and the eastern (O. barnabita Motschulsky, 1845 and O. lassalei Baraud & Tauzin, 1991), occurring throughout Eastern Europe (Audisio et al. 2009). Since ecological studies that would indicate the differences between putative Osmoderma species are so far missing, there is still no agreement whether these taxa should be treated as separate species or only subspecies within O. eremita in a broad meaning. According to the division proposed by Audisio et al. (2009) the population investigated in this study was identified as O. barnabita, which was verified by sequencing analysis of the COI region (Svensson et al. 2009, sequences deposited in GeneBank under numbers FJ98457–FJ984581) and PCR–RFLP analyses (Oleksa et al. unpubl. data).

Beetles of the O. eremita species complex inhabit hollows developing in several tree species (Ranius et al. 2005; Oleksa 2009). In the study area O. barnabita occurs mainly on T. cordata, but it has been found also on six other tree species (Alnus glutinosa, Quercus robur, Fraxinus excelsior, Aesculus hippocastanum, Carpinus betulus and Salix alba; Oleksa et al. 2007). However, when the occurrence of O. barnabita was compared with host tree accessibility (the number of suitable trees), it turned out that T. cordata was highly preferred, while occupancy in other species did not deviate from their relative occurrence in the area, and some trees were even avoided (especially Acer spp.). In addition, Dubois et al. (2009a, b) demonstrated that O. eremita preferred or avoided several tree species, but also that the abundance of preferred tree species varied geographically.

Protaetia marmorata (Herbst, 1786) (also known as Liocola marmorata or Protaetia lugubris) is regarded as being a species of least concern according to recent evaluation of the threat status of European beetles (Nieto and Alexander 2010). The species seems to be more common in the eastern parts of Europe and Burakowski et al. (1983) claimed that it has a more continental distribution. It is considered vulnerable in Germany (Geiser et al. 1984) and endangered in Austria (Jäch et al. 1994). In Sweden, its range contracted during the last century and the species completely disappeared from the southwestern part of the country (Nilsson et al. 2002). The conservation status of P. marmorata in Poland has not been systematically evaluated, and so far it is not protected despite its assumed status of being critically endangered (Bunalski 2008). However, it is locally abundant in the survey area of this study and much more widespread than O. barnabita. Oleksa and Gawroński (2006) found its presence in 70 of 165 surveyed 2.5 × 2.5 km squares (42.4 %), while O. barnabita occurred in only 45 squares (27.3 %). In addition, P. marmorata shows no clear preferences for tree species. It was found on seven species in the study area (T. cordata, F. excelsior, Acer platanoides, Q. robur, C. betulus, S. alba and A. glutinosa), but its distribution was random with respect to tree species identity (i.e. number of occupied trees of each species was dependent only on their availability, Oleksa et al. 2006). Given the prevalence of hollow trees of different species (Oleksa et al. 2006, 2007 and unpublished habitat inventories), suitable host trees for P. marmorata are approximately 1.5 times more frequent than appropriate trees for O. barnabita.

Area under study

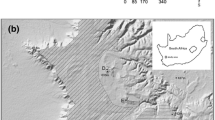

For this study, samples of O. barnabita and P. marmorata were collected in rural avenues in northern Poland in 2008 and 2009 in the area between the Lower Vistula Valley and the Great Masurian Lakes, between 18°56′–21°43′E and 53°16′–54°19′N (Fig. 1). The study area is dominated by a rural landscape rich in avenues with trees planted along roads. Some of the avenues are dating back to the early 18th century, when the kings of Prussia mandated the planting of trees along most roads of their realm (Płoski 2009). Today the most common tree species in these avenues is T. cordata (ca. 50 % of all trees in avenues), followed by Q. robur, F. excelsior, and A. platanoides (each species representing approx. 10 % of all trees, Oleksa et al. 2006, 2007).

Sampling

Sampling was designed to quantify the spatial structure of genetic data over different spatial scales, from a few meters to over 100 km. In studies of this kind the potential difficulty is to design sampling in order to capture real spatial extent of a process. In our study we employed spatially nested design, which outperforms other sampling strategies in identification of real spatial scale of a pattern (Fortin and Dale 2005). The distances between sampling locations varied to cover different spatial scales, from species daily movement to beyond putative dispersal capacity. Within the whole region, we randomly selected several avenues recognized as occupied by the studied beetles in previous studies (Oleksa et al. 2006, 2007; Oleksa 2009). Samples were collected within selected sections of tree-lined roads in a continuous manner so as to provide a large number of pair-wise comparisons between genotypes for different geographical distances. Beetles were caught with pheromone traps (only O. barnabita) or directly on tree trunks and within cavities. Pheromone traps were suspended from tree branches and dispensers were loaded with the male-produced sex pheromone of O. barnabita, (R)-(+)-γ-decalactone, or a racemic mixture (for detailed information about the trapping method, see Svensson et al. 2009).

For collection of beetle tissue, the tarsus of one middle leg was cut off with scissors and stored in absolute ethanol. After amputation of tarsi, the beetles were released back into the hollow entrances, or placed on a tree trunk close to the pheromone trap they were captured in. At the beginning of the study, six treated P. marmorata were kept in the laboratory for over 10 months, which indicated that the amputation of tarsi did not cause increased mortality, at least under laboratory conditions. This is likely to be true also under natural conditions, as we regularly recaptured individuals with missing tarsi. Altogether, samples from 200 individuals of both species were collected and preserved in −20 °C until DNA extraction.

DNA extraction and AFLP analysis

Genomic DNA was extracted using the Insect Easy DNA Kit (EZNA) (Omega Bio-Tek, Norcross, GA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. High quality DNA isolates were obtained for 164 individuals of O. barnabita and 175 P. marmorata and only these samples were included in further analyses. The AFLP analysis generally followed the original protocol by Vos et al. (1995). Restriction-ligation reactions were carried out in a total volume of 10 μl. A single reaction contained 500 ng of genomic DNA, 5 U EcoRI (MBI Fermentas, Vilnius, Lithuania) and 5 U TruI (MseI isoschizomer) (Fermentas), 1.5 U T4 DNA Ligase (Fermentas), 1× T4 DNA Ligase Buffer (Fermentas), 0.05 % BSA, 50 mM NaCl, 0.5 pmol/μl E-Adaptor and 5 pmol/μl M-Adaptor. Reactions were carried out at room temperature overnight and then diluted 5× with H2O in order to obtain PCR matrices (pre-matrix DNA) for pre-selective amplification.

Pre-selective amplifications were carried out in 10 μl total volume. A pre-selective PCR mixture contained 2 μl pre-matrix DNA, 1× Qiagen Master Mix (Qiagen Taq PCR Master Mix Kit; Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), 0.5 μM E-primer (E + A) and 0.5 μM M-primer (M + C). Amplification was carried out using the following program: 72 °C for 2 min, 20 cycles of 94 °C for 20 s, 56 °C for 30 s and 72 °C for 2 min, and finally 60 °C for 30 min. A product of pre-selective PCR was diluted 20 times in order to obtain a PCR matrix for selective amplification (sel-matrix DNA).

Selective amplifications were carried out in 10 μl total volumes, consisting of 3 μl sel-matrix DNA, 1× Qiagen Master Mix, 0.5 μM FAM-labelled E-primer (E + ACA or E + ACG) and 0.5 μM M-primer (M + CAC, M + CGG, M + CCCC or M + CCCT). PCR reaction was performed with the following program: 94 °C for 2 min., 10 cycles of 94 °C for 20 s, 66 °C (−1° per cycle) for 30 s and 72 °C for 2 min, 20 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 56 °C for 30 s and 60 °C for 30 min. Both pre-selective and selective amplifications were carried out using PTC200 thermocycler (BioRad, Hercules, CA, USA). Reproducibility of results was tested by carrying out the whole AFLP protocol twice for 20 individual samples randomly chosen across populations as recommended by Bonin et al. (2004).

The products of selective amplifications were sized using automated capillary sequencer ABI3130XL (Appllied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and the manufacturer’s Genescan 3.7 software. AFLP profiles were then subjected to visual assessment in order to eliminate outlier samples in Genotyper 3.7 software (Applied Biosystems). Then, all peaks in a profile within the range 60–400 bp were automatically labelled and bins were created based on all labelled peaks. Automatically created bins were visually checked to ensure that the bin was centred on the distribution of peaks within the bin. We also removed bins that had AFLP fragments that differed in size by more than 1 bp, bins with fragment-length distributions that overlapped with adjacent bins to reduce the occurrence of homoplasy (Vekemans et al. 2002) and bins with low polymorphism (3 % < frequency of dominant haplotype < 97 %). Raw peak intensity data output from Genotyper were subsequently transformed into a binary data matrix with AFLPScore R-script (Whitlock et al. 2008).

Statistical methods

Genetic variation

Studied beetles are distributed across the landscape along tree-lined roads and without complete inventory of avenues over the whole region it is difficult to indicate clear discontinuities that could be used to specify the boundaries between populations. However, for the purposes of analysis we assumed that the beetles caught along one tree-lined road and isolated by more than 1 km from other sampling sites formed distinct group of individuals (“population”). To avoid bias resulting from small sample size, for estimation of variation we included only sites where at least 10 individuals were sampled (Fig. 1, Table 1). For each population, after estimating allelic frequencies with a Bayesian method, assuming a non-uniform prior distribution of allele frequencies (AFLP-SURV ver.1.0, Vekemans et al. 2002), the following statistics were computed: number and proportion of polymorphic loci at the 5 % level; expected heterozygosity or Nei’s gene diversity (Hj) and Wright’s F ST .

Spatial genetic structure

To check for the relationship between genetic and geographic pair-wise distances, we used Mantel’s test (Mantel 1967) in the PAST software package (Hammer et al. 2001) to calculate the correlation between matrices of genetic distances (linearized F ST transformation F ST /(1 − F ST )) and log-transformed geographic distances (Slatkin 1995). However, this population-based approach assumes an island model of population structure, which may not reflect the true structure. Assigning sampling individuals to discrete groups even if the population is continuously distributed could result in failure to detect the real spatial genetic structure (Schwartz and McKelvey 2009). Therefore we applied spatial autocorrelation analysis using a multi-locus kinship coefficient (Hardy and Vekemans 1999). In contrast to population genetic estimators, which require averaging across populations or hierarchical levels, spatial autocorrelation makes no assumptions about the spatial scale of structuring in populations. Moreover, autocorrelation method makes full benefit of data from all pairs of individual locations across the sampled space and therefore accesses much more of the available information at the population scale than usually applied population genetic estimators. The analysis was carried out for AFLP markers using SPAGeDi ver. 1.3 software (Hardy and Vekemans 2002). To visualize the strength of spatial genetic structure, we plotted average pair-wise kinship coefficients against distance classes. Because the relationship between kinship coefficients and distance typically takes log-linear form (Rousset 2000), major changes in the spatial genetic structure are supposed to occur at closer distances. Therefore distance intervals for kinship comparisons were constructed in such a way that each successive interval was 2–2.5 times longer than the previous. These classes were selected empirically to get as much detailed overview of the spatial genetic structure as possible while simultaneously obtaining the smoothed curves (Olivier Hardy, pers. com.). Average pairwise kinship coefficient per geographic distance interval was computed for the following distance classes: approx. 1 m (=within a single tree), 25 m, 50 m, 100 m, 200 m, 400 m, 800 m, 1.6 km, 3.2 km, 6.4 km, 12.8 km, 25.6 km, 51.2 km, 102.4 and over 102.4 km (O. barnabita) and 1 m, 150 m, 375 m, 937.5 m, 2.34 km, 5.86 km, 14.65 km, 36.62 km, 91.55 km and over 91.55 km (P. marmorata). Confidence intervals around observed average kinship coefficients for a given distance class were obtained from standard errors calculated by jack-knifing data over loci. The differences in the adopted distance classes were associated with different numbers of samples collected at closer distances. For O. barnabita, it was possible to get more samples from less distant trees due to males’ behaviour of perching around hollow entrances when emitting sex pheromones and achieve more detailed description of pairwise kinship coefficient at closer distances. It should be noted, however, that the estimation of the total regression parameters was computed over the complete data from all pairwise comparisons and was not dependent on the assumed distance classes.

Under isolation-by-distance, given drift-dispersal equlibrium, kinship is a linear function of logarithm of distance between individuals (Rousset 2000). Therefore, in order to illustrate intensity of the spatial genetic structure, we estimated Sp = −b 1/(1 − f (1)) index (Vekemans and Hardy 2004), where b 1 is a slope of a log-linear regression between observed kinship and a distance between individuals, and f (1) is the average kinship for the first distance class. Given that Sp is inversely proportional to the effective size of the Wright’s neighbourhood (Nb), the latter parameter was also calculated. The confidence intervals were estimated using the standard error calculated by jack-knifing over loci. Finally, Nb estimates were used to approximate an axial variance of dispersal (σ), a measure of a total gene flow close to the average distance of dispersal. Nonetheless, as the effective density (De, expressed as number of individuals/km2) remains unknown, a series of guesses on De (Table 3) were used in the estimation. Based on our mark-release-recapture survey (Svensson et al. 2009, 2011) we expect that the population density in the studied landscape was not higher than 50 individual per 1 km2. Given the high inbreeding levels, strong spatial structuring and the lack of gene flow between cohorts resulting from 3 to 4 year life cycle we could expect that the effective population density could be even one order of magnitude smaller than the census density (Waples 2002). The estimation of σ was performed using an iterative procedure implemented in SPAGeDi, based on the regression restricted to a distance range from σ to 20σ.

Since our main focus was to study spatial genetic structure (SGS) and SGS may arise both due to isolation by distance or due to spatial variation of selective forces affecting distribution of alleles of specific loci (Beaumont and Nichols 1996; Beaumont and Balding 2004), only neutral loci were included in the analyses of SGS. For this purpose, we used Mcheza, the AFLP-dedicated version of Lositan (Antao and Beaumont 2011) to identify outlier loci, i.e. the loci considered to be candidates for directional and stabilizing selection. Mcheza implements popular DFDiSt method for dominant markers (Beaumont and Nichols 1996) which relies on a Bayesian estimate of locus frequency (Zhivotovsky 1999). Locus-specific F ST values were estimated from a simulated distribution of 50,000 iterations using an infinite alleles model. The resulting distribution was used to find outliers. Outlier loci falling above the 0.99 quantile were considered putatively under directional selection, while under stabilizing selection when falling under 0.01. These markers were omitted from the further SGS and inbreeding analyses.

Inbreeding

AFLP markers were analysed under the assumption of complete dominance (binary data). Hence, inference about inbreeding needs simultaneous estimation of allele frequencies and the inbreeding coefficient, based on phenotypes. The estimation was carried out using a Bayesian method introduced by Chybicki et al. (2011) and implemented in I4A computer program. The method is a modification of simultaneous estimation of null alleles and inbreeding coefficient elaborated for codominant markers (Vogl et al. 2002; Chybicki and Burczyk 2009). The estimation procedures are described in details in the manual accompanying the software (Chybicki 2010). Briefly, the method assumes that a sample of individuals, genotyped at AFLP loci, is randomly taken from a population characterized by an unknown average inbreeding coefficient (F). Each sampled individual is characterized by an individual inbreeding coefficient (F i ) that by assumption follows a beta distribution. Generally, a probability of observing a multilocus phenotype is a function of both (unknown) allele frequencies and (unknown) individual inbreeding coefficient (as a proportion of identical by descent alleles in genotype of an individual). Using a Markov Chain Monte Carlo approach (mixed Gibbs-Metropolis algorithm), I4A estimates simultaneously marginal posterior distributions of the average inbreeding coefficient and allele frequencies given provided phenotypic data. Our estimates were obtained after 100,000 steps, after 10,000 burn-in steps. Because the method requires initial guesses on the priors, which are shape parameters of beta distribution (α and β) such, that F = α/(α + β), to avoid a dependence of final results on these guesses, analyses were conducted starting from three initial sets of parameters (α = β = {0.1,1,5}). Each set determines the same mean (F = 0.5) but implies very different shape (and variance) of the prior distribution.

Results

Genetic variation

While scoring phenotypes, special care was taken to incorporate only those loci, which showed a stable migration pattern and peak intensity across samples. Using four combinations of primers, we reliably scored 95 marker loci in O. barnabita and 101 loci in P. marmorata. Additional fragments were present but could not be scored either because of the difficulty to distinguish between two or more fragments of a similar mass or due to a vague amplification. F ST -outlier method revealed some loci to be positively exceeding neutral expectations in the two species (4 loci in O. eremita and 12 in P. lugubris), leaving 91 and 89 neutral loci for further analyses. Populations of P. marmorata showed higher level of diversity, both in terms of proportion of polymorphic loci and heterozygosity (Table 1). The average unbiased expected heterozygosity for all populations was equal to 0.209 ± 0.002 for O. barnabita and 0.290 ± 0.002 for P. marmorata, while the average proportion of polymorphic loci was 0.635 and 0.805, respectively. Populations of O. barnabita were more differentiated with respect of both parameters, e.g. heterozygosity in O. barnabita ranged from 0.160 to 0.303, while in the second species this range was smaller (from 0.270 to 0.306). A higher degree of differentiation in O. barnabita in comparison with P. marmorata was also demonstrated by F ST index (0.110 and 0.027, respectively).

Spatial genetic structure

Mantel test showed that matrices of genetic and geographic distances between studied populations were correlated (r = 0.518 for O. barnabita and r = 0.264 for P. marmorata, both values significant at p < 0.05). Also individual-based autocorrelation analysis revealed significant relationships between genetic and geographical distances in both species (Fig. 2). All descriptive measures of spatial genetic structure were significantly different from zero (Table 2). As can be expected under isolation-by-distance, the nearest neighbours exhibited the highest kinship, which then decreased about log-linearly with increased distance (Fig. 2). In O. barnabita, there was a strong kinship among individuals sampled at the single tree level (f ij = 0.263), and positive pair-wise kinship coefficients values for individuals living up to 10 km apart. Autocorrelations over ca. 10 km were negative and the correlogram was distinctly greater from zero for distances up to 100 km, after which it levelled off and showed no clear difference from zero. In P. marmorata, spatial structuring was much less intensive. Only individuals in the closest distances (up to 250 m) showed significant spatial autocorrelation. All three parameters characterizing spatial genetic structure, i.e., the kinship among beetles collected in the same tree (f ij(1)), the slope of the log-linear regression (b 1 ), and the spatial genetic structure intensity measure (Sp), were significantly higher in O. barnabita than in P. marmorata (p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Average kinship coefficients between pairs of individuals plotted against the logarithm of geographical distance in the whole population. The observed value of pairwise kinship coefficient for mean value of each distance class, its 95 % confidence interval obtained under the null hypothesis that genotypes are randomly distributed (dashed line) and standard error obtained by jack-knifing over loci (error bar) are shown

Gene flow estimates

Using the iterative procedure implemented in the SPAGeDi software, under the assumption of isolation-by-distance, we estimated the two characteristics of gene flow intensity: the Wright’s neighbourhood size (Nb) and the axial variance of dispersal (σ), the latter being a measure similar to the mean dispersal distance. The results from the analysis are shown in Table 3. Generally, the presence of convergence for most realistic values of assumed effective density (De) suggests a good agreement between the observed correlograms and the theory of isolation-by-distance in O. barnabita. In P. marmorata, however, values of Nb and σ could not be estimated due to lack of convergence or the estimates were loaded with large variances, indicating that the assumptions of isolation-by-distance could be violated for this species. Our data show that O. barnabita is characterized by at least 3–6.5 times smaller neighbourhood size and than P. marmorata. Similar conclusions apply to the dispersal parameter (1.7–2.5 times smaller in O. barnabita), as a result of the stronger spatial genetic structure in O. barnabita. The axial variance of dispersal in that species was estimated to be about 500 m for the highest values of effective density for which the simulation achieved convergence (50 individuals/km2).

Inbreeding

For each species three independent analyses were run, each starting from different initial values of the prior beta distribution (see “Materials and Methods”). All analyses conducted for each species converged to almost the same posterior distributions of the inbreeding coefficient (Table 3) even though these initial prior distributions differ much in shape (from concave to convex curves). Also the likelihood behaviour across different priors (e.g. similar average and standard error values of LogL) proved that the model was stable. The analyses revealed substantial inbreeding of the studied populations. The mean individual inbreeding coefficient was slightly higher in O. barnabita than in P. marmorata, ranging from 0.174 to 0.181 and from 0.104 to 0.114, respectively, depending on initial values of the prior beta distribution. Nonetheless, O. barnabita and P. marmorata did not differ statistically in F at p = 0.05, as can be deduced from wide credible intervals (Table 4).

Discussion

Spatial genetic structure

Our analysis of spatial genetic structure of two beetle species dependent on tree hollows strongly indicates that these insects are highly influenced by limited gene flow and isolation by distance (Wright 1943). In particular, the high kinship coefficients at short distance classes are in good agreement with presumed restricted dispersal. Although both species showed significant spatial population structure resulting from limited gene flow, the intensity of spatial structure was higher in O. barnabita, the species with a more restricted ecological niche and presumably more limited flying propensity, compared to P. marmorata, the species with a broader ecological niche and less constrained dispersal ability. Similar patterns of isolation-by-distance were previously reported for other comparisons of related species differing in niche breadth or details of life history (e.g. Brouat et al. 2003; Soto et al. 2007; Oddou-Muratorio et al. 2010). However, most studies have been devoted to sessile plants, and there are only a few species-pair comparisons available for saproxylic invertebrates. Ranius and Douwes (2002) compared the genetic structures of two saproxylic pseudoscorpion species, Larca lata and Allochernes wideri, with considerable differences in ecological specialisation. Isolation-by-distance was moderate in the more specialised species and was lacking in the generalist, although the authors concluded that these differences did not point to differences in dispersal rates because larger differentiation between sites in the more specialised species could be attributed to its smaller population size. Jonsson et al. (2003) compared the genetic structure of the threatened tenebrionid beetle Oplocephala haemorrhoidalis, living in sporocarps of a bracket fungus, and its common relative Bolitophagus reticulatus. The genetic differentiation between studied populations and isolation-by-distance were apparent in the rare and specialised O. haemorrhoidalis, but weak in the more widespread B. reticulatus.

It should be noted, however, that the results cited above are not fully comparable with ours because the inferences about dispersal abilities were made with a different approach. In most dispersal studies of animals, dispersal is inferred as ‘numbers of effective migrants’ (N e m) between populations from F-statistics under the assumption of Wright’s (1931) island model. Isolation-by-distance is then assessed by regressing log-transformed N e m estimates against the log-transformed geographic distances separating discrete populations (Slatkin 1993). Furthermore, population-based metrics of genetic distance such as F ST —based statistics assume an island model of population subdivision, which may not be an appropriate approximation of the real structure. Such population-based approach dramatically reduces the number of observations for pair-wise comparisons, which is especially disadvantageous for species that are rare and difficult to sample. Analysis of spatial autocorrelation provides an alternative way to study isolation-by-distance and could be more appropriate in cases when island habitat structure is less apparent. Information on dispersal distances may be inferred from patterns of population spatial genetic structure by fitting the Wright’s (1943) model of isolation-by-distance, where genetic variation among individuals is not random due to limited dispersal. Moreover, an individual-based model reduces the number of samples required to achieve high statistical power. In an extensive simultaneous study of demographic and genetic data sets, Watts et al. (2007) demonstrated that the pattern of spatial genetic structure provides an estimate of N b (Rousset 1997, 2001), which is equivalent to that obtained from ecological observations.

In our study, we tried to show that differences in spatial genetic structure between O. barnabita and P. marmorata may be a function of habitat availability. Despite the fact that we choose closely related species with overlapping distributions, thus controlling for both phylogenetic and geographic effects, there could be, however, alternative explanations of observed patterns. First of all, differences could also be impacted by different population histories. Differences in effective population size could result in faster drift in one species, resulting in faster lineage sorting and more pronounced genetic structure. These species may have different recolonization histories after the last glacial period, either due to intrinsic factors of each beetle species, or due to different dynamics of the trees that they live in. Unfortunately, our data are insufficient to test these additional hypotheses, providing perspectives for further studies.

Gene flow estimates

Our estimates of gene flow intensity depended much on the assumed effective population density, which in fact is unknown for the studied populations, and can be even lower than assumed, as the number of individuals in each generation contributing to gene pool is often limited (Frankham 1995). Nevertheless, our estimates suggest that gene flow in O. barnabita is fairly limited and could be moderate in P. marmorata. As it was expected, the intensity of gene flow was greater in the less specialised P. marmorata, which has a larger number of potentially suitable trees to occupy. This finding is in line with the assumption that costs of dispersal are increasing when the density of suitable habitat patches is decreasing and their distribution is becoming less predictable (Travis and Dytham 1999). However, estimates of dispersal in P. marmorata were loaded with large variances, indicating that the assumptions of isolation-by-distance could not be met due to high levels of gene flow or due to insufficient sampling design (area sampled).

Our results suggest that the dispersal ability of O. barnabita could be one order of magnitude larger than those suggested by previous mark-release-recapture and telemetric studies performed on Swedish populations of the sister species O. eremita (Ranius and Hedin 2001; Hedin et al. 2008), which pointed to 60 m as an average dispersal distance. In O. barnabita, the axial variance of dispersal, a measure very close to the average distance of dispersal, was estimated to be at least 200 m. Comparison of molecular and direct estimates would be very instructive for understanding dispersal propensity of O. barnabita, but such direct estimates are currently lacking for the studied populations. A mark-release-recapture experiment on O. barnabita was recently performed in the area under study using pheromone traps (Svensson et al. 2009, 2011). In total, 43 captures of 34 females were recorded, with seven females recaptured once and one female recaptured twice. All but one recapture were done on the same tree or its closest vicinity, indicating limited dispersal propensity. However, it should be noted that one female moved 780 m between two sites of the study area. A similar observation was done in western Poland by Mokrzycki et al. (2008) who followed one individual of O. barnabita flying from one group of oaks to another about 400 m away, and in France, where the range of movements of radio-tagged O. eremita reached almost 700 m (Dubois and Vignon 2008). These observations indicate that dispersals over several 100 m may be common not only in O. barnabita, but also in other populations of the O. eremita species complex.

Observations of longer movements of hermit beetles are also well corroborated by experiments with tethered flight performed on O. eremita (individuals from French population, Dubois et al. 2009a, b, 2010), which revealed that during a single flight the distance of 1.4 km may be reached, and the maximal total flight distance of 2.4 km was observed. The differences in dispersal distances observed between Osmoderma populations from different geographic regions of Europe may be explained by various selective pressures acting on the beetles in different landscape types (low vs. high landscape connectivity; Wiens 2001). For example, the studied populations in Sweden inhabit relatively large oak stands with high densities of suitable trees but surrounded by inhospitable matrix, whereas Polish or French populations inhabit large networks of trees in avenues which may function as efficient dispersal corridors and thus facilitate long-range movements.

Inbreeding

Individual inbreeding coefficients are of great interest for conservation biologists, mainly because of the risk of inbreeding depression that in turn might drive the extinction of small populations (O’Grady et al. 2006). Unfortunately, data on inbreeding levels in saproxylic invertebrates are scarce, and according to our knowledge, no previous estimates of inbreeding in beetles of the genera Osmoderma nor Protaetia are currently available. In this study, the levels of inbreeding were estimated using AFLP markers and a Bayesian approach, which takes full advantage of multi-locus data, and to our knowledge, this is the first study of insects where individual inbreeding coefficients have been estimated with dominant markers. Previous studies on inbreeding in saproxylic invertebrates have used allozyme data at a population level based on Wright’s F-statistics. In general, large effective population size and the lack of assortative mating should prevent inbreeding. For example, using isozymes Ranius and Douwes (2002) detected no inbreeding in two species of pseudoscorpiones living in tree hollows. These small-bodied pseudoscorpions form large, almost panmictic populations in tree cavities with no signs of mating between relatives. However, significant inbreeding may result from the bottleneck during population establishment as it was observed in saproxylic Ptinidae (Hamilton 1978). These beetles produce wingless generations after successful colonisation of decaying wood by few winged individuals, forming an inbreeding ‘multiplication phase’. Winged adults appear only when the substrate quality deteriorates forcing the population to find a new habitat patch (Hamilton 1978).

Inbreeding may also result from restrictions in dispersal due to low spatial connectivity among populations. For example, in Apasis puncticeps, an Australian tenebrionid beetle dependent on decaying Eucalyptus logs, inbreeding in a local population increased with decreasing connectivity of the habitat patch (number of potential dispersal barriers between a fragment and the continuous forest; Schmuki et al. 2006). Both mechanisms, i.e., small effective number of founder individuals during habitat colonisation, and restricted gene flow between habitat patches, may potentially be responsible for substantial amounts of inbreeding in both O. barnabita and P. marmorata. The latter species should be less prone to inbreeding due to the greater extent of gene flow, but our data did not reveal such a difference. We could only speculate that the less mobile species could have developed efficient mechanisms to avoid mating between related individuals.

In our study, individuals of both species sampled within one tree showed a high kinship coefficient (0.267 in O. barnabita and 0.072 in P. marmorata). The kinship coefficient is a measure of relatedness between two individuals. It represents the probability that two genes, sampled at random from each individual are identical (e.g. the kinship coefficient between a parent and an offspring is 0.25, Lange 1997). Our data thus show that beetles collected within one tree were highly related, especially in O. barnabita, where groups of males sampled on the same tree trunks when emitting their sex pheromone were full brothers. A presence of highly related males on the same trunk can possibly be explained by a lack of dispersal since metamorphosis, which could be explained by noting that: (1) males don’t need to disperse because they actively attract females; (2) they already inhabit a suitable hollow tree that can further attract females; (3) brothers can cooperate to attract females more effectively; (4) they don’t need to seek food intensively. On the other hand, females need to disperse mainly because they need to seek opportunity for insemination. Thus, it seems that sex-specific costs of dispersal would select for sex-biased dispersal in the genus Osmoderma and the sex mainly responsible for effective dispersal is females. Some earlier results support this hypothesis—for example, during a radio telemetry study Hedin and Ranius (2002) found that 71 % of the tagged females of O. eremita ceased to be locatable, while the corresponding proportion in males was only 20 %. Although the authors attribute the higher rate of contact loss in females to differing behaviour of the two sexes (more digging movements within tree hollows when laying eggs, combined with a damage of the transmitter or the antenna), an alternative explanation is that some females had dispersed out of the study area, especially if the search radius during the study was limited to 800 m. Also, examples of the longest detected flights of hermit beetles cited in the previous section were noted in females. Sex-biased dispersal seems to be very likely in studied beetles, especially since even small differences in dispersal costs and profits could result in a severe bias in dispersal between sexes (Gros et al. 2008). However, further specifically dedicated studies (including those based on sex linked loci, Prugnolle and de Meeu 2002) are needed in that field.

Inbreeding is usually seen as a negative phenomenon, which reduces individual fitness. However, moderate inbreeding levels might be even advantageous under some circumstances (reviewed by Perrin and Goudet 2001). First, outbreeding may result in the breakdown of locally adapted gene complexes (for examples, see Sagvik et al. 2005). Second, the cost of dispersal may outweigh those of inbreeding, especially when taking into account the high mortality during the dispersal stage (Johnson et al. 2009) and low probability of finding a suitable habitat patch in a fragmented landscape (With and King 1999). Finally, inbreeding facilitates achieving a high level of relatedness between individuals, which might be advantageous as a prerequisite for the evolution of cooperation between individuals (Hamilton 1964). In our study, groups of pheromone-emitting O. barnabita males sampled on the same tree trunk were found to be full brothers. Whether this result can be explained by kin selection to increase attraction of conspecific females for mating or by severe inbreeding of beetles within individual tree hollows needs further study.

Implications for conservation

The knowledge on population genetic consequences of habitat fragmentation for saproxylic species is limited (Ranius 2006), although such information is extremely important for planning appropriate conservation measures for species of this endangered fauna. In particular, the estimates of dispersal abilities allow for determining acceptable levels of habitat fragmentation. The results of this study show that P. marmorata should not be regarded as critically endangered in Poland as was proposed by Bunalski (2008). This species has a wide spectrum of host trees (Oleksa et al. 2006), and quite large dispersal propensity, which enables colonisation of suitable trees also at more isolated sites (Oleksa and Gawroński 2006). On the other hand, we found that the studied population is significantly inbred, probably because of a small effective population size. Consequently, we propose to classify the status of P. marmorata in Poland as “near threatened” or “least concern” according to IUCN criteria (IUCN 2003). In contrast, the data obtained for O. barnabita in this study confirm that this species could be potentially endangered by isolation by distance, but it is probably less affected by loss of habitat continuity than previously thought based on the data obtained for sister species O. eremita (Ranius and Hedin 2001; Hedin et al. 2008). It should be emphasized that the dispersal capacity was assessed in a landscape of high connectivity, which was ensured by the reticular structure of avenues with trees planted along roads. Such habitat structure facilitates the dispersal of saproxylic organisms even if they have limited dispersal potential. Unfortunately, the current need for infrastructure development and traffic safety improvement has caused large-scale cutting of roadside trees, and the decline of mature trees in cultural landscapes posses the most serious threat for the maintenance of hermit beetles and related species in Poland (Oleksa 2009) as well as other parts of Europe (Carpaneto et al. 2010; Nieto and Alexander 2010). In order for conservation efforts to be successful, there is an urgent need to determine not only the dispersal propensity of saproxylic beetle species, but also to understand how their potential to colonise new habitat patches depends on the density of suitable trees in the landscape.

Additionally, further studies are needed to relate individual inbreeding of Osmoderma beetles with their fitness. As discussed above, elevated inbreeding could have harmful consequences for fitness of studied beetles or just the opposite—some inbreeding and the existence of distinct kin structure could be even advantageous. Because no data on inbreeding depression are available, further studies are needed to resolve whether these features should be treated as disadvantageous or rather nature of a species (due to evolutionary strategy). The resolution of this matter is urgent taking into account the currently used conservation measures during felling of trees for infrastructure development. A common practice is the translocation of individuals from the felled trees to the existing populations. This kind of refill of foreign genes can be advantageous if the inbreeding has detrimental effect on population survival. However, if there is an intrinsic genetic advantage resulting from some level of inbreeding, then special care should be taken when translocating Osmoderma beetles between distantly related populations to avoid outbreeding depression.

References

Anonymous (1992) Directive 92/43 of the Council of the European Community on the Conservation of Habitats and Wild Fauna and Flora. European Community, Brussels, Belgium

Antao T, Beaumont M (2011) Mcheza: a workbench to detect selection using dominant markers. Bioinformatics 27:1717–1718

Audisio P, Brustel H, Carpaneto GM, Coletti G, Mancini E, Piattella E, Trizzino M, Dutto M, Antonini G, De Biase A (2007) Updating the taxonomy and distribution of the European Osmoderma, and strategies for their conservation (Coleoptera, Scarabaeidae, Cetoniinae). Fragm Entomol 39:273–290

Audisio P, Brustel H, Carpaneto GM, Coletti G, Mancini E, Piattella E, Trizzino M, Dutto M, Antonini G, De Biase A (2009) Data on molecular taxonomy and genetic diversification of the European hermit beetles, a species complex of endangered insects (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae, Cetoniinae, Osmoderma). J Zool Syst Evol Res 47:88–95

Beaumont MA, Balding DJ (2004) Identifying adaptive genetic divergence among populations from genome scans. Mol Ecol 13:969–980

Beaumont MA, Nichols RA (1996) Evaluating loci for use in the genetic analysis of population structure. Proc R Soc B 263:1619–1626

Bonin A, Bellemain E, Eidesen PB, Pompanon F, Brochmann C, Taberlet P (2004) How to track and assess genotyping errors in population genetics studies. Mol Ecol 13:3261–3273

Brouat C, Sennedot F, Audiot P, Leblois R, Rasplus J-Y (2003) Fine-scale genetic structure of two carabid species with contrasted levels of habitat specialization. Mol Ecol 12:1731–1745

Bunalski M (2008) Scarabaeoidea. In: Bogdanowicz W, Chudzicka E, Pilipiuk I, Skibińska E (eds) Fauna of Poland—characteristics and checklist of species. Zoological Museum and Institute of the Polish Academy of Science (PAN), Warsaw, pp 139–145

Burakowski B, Mroczkowski M, Stefańska J (1983) Chrząszcze [Beetles]—Coleoptera. Scarabaeoidea, Dascilloidea, Byrrhoidea i Parnoidea. Katalog fauny Polski [Catalogue of the fauna of Poland]. Polish Scientific Publishers, Warsaw 23(9):1–294 (in Polish, Eng. Sum.)

Carpaneto GM, Mazziotta A, Coletti G, Luiselli L, Audisio P (2010) Conflict between insect conservation and public safety: the case study of a saproxylic beetle (Osmoderma eremita) in urban parks. J Insect Conserv 14:555–565

Chybicki IJ (2010) I4A, Inbreeding For AFLP—the user manual. Kazimierz Wielki University, Bydgoszcz, Poland [online] url: http://www.genetyka.ukw.edu.pl/index_pliki/software.htm

Chybicki IJ, Burczyk J (2009) Simultaneous estimation of null alleles and inbreeding coefficients. J Hered 100:106–113

Chybicki IJ, Oleksa A, Burczyk J (2011) Increased inbreeding and strong kinship structure in Taxus baccata estimated from both AFLP and SSR data. Heredity 107:589–600

Dajoz R (2000) Insects and forests. The role and diversity of insects in the forest environment. Intercept, Londres

Dubois G, Vignon V (2008) First results of radio-tracking of Osmoderma eremita (Coleoptera: Cetoniidae) in French chestnut orchards. Rev Ecol Terre Vie 63:131–138

Dubois GF, Vernon P, Brustel H (2009) A flight mill for large beetles such as Osmoderma eremita (Coleoptera: Cetoniidae). In: Buse J, Alexander KNA, Ranius T, Assmann T (eds) Saproxylic beetles—their role and diversity in European woodland and tree habitats. Pensoft Series Faunistica 89:219–224

Dubois GF, Vignon V, Delettre YR, Rantier Y, Vernon P, Burel F (2009) Factors affecting the occurrence of the endangered saproxylic beetle Osmoderma eremita (Scopoli, 1763) (Coleoptera: Cetoniidae) in an agricultural landscape. Landsc Urban Plan 91:152–159

Dubois GF, Gouar PJ, Delettre YR, Brustel H, Vernon P (2010) Sex-biased and body condition dependent dispersal capacity in the endangered saproxylic beetle Osmoderma eremita (Coleoptera: Cetoniidae). J Insect Conserv 14:679–687

Fahrig L (2003) Effects of habitat fragmentation on biodiversity. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst 34:487–515

Fortin M-J, Dale M (2005) Spatial analysis. A guide for ecologists. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Frankham R (1995) Effective population size/adult population size ratios in wildlife: a review. Genet Res 66:95–107

Frankham R (2005) Genetics and extinction. Biol Conserv 126:131–140

Futuyma DJ, Moreno G (1988) The evolution of ecological specialization. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 19:207–233

Geiser R et al (1984) Käfer (Coleoptera). In: Blab J et al (eds) Rote Liste der gefährdeten Tiere und Pflanzen in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Kilda, Greven, pp 75–113

Gros A, Hovestadt T, Poethke HJ (2008) Evolution of sex-biased dispersal: the role of sex-specific dispersal costs, demographic stochasticity, and inbreeding. Ecol Model 219:226–233

Hamilton WD (1964) Genetical evolution of social behaviour I & II. J Theor Biol 7:1–32

Hamilton WO (1978) Evolution and diversity under bark. In: Mound LA, Waloff N (eds) Diversity of insect faunas. Symposium of the Royal Entomological Society of London 9:156–175

Hammer Ø, Harper DAT, Ryan PD (2001) PAST: paleontological statistics software package for education and data analysis. Palaeontol Electronica 4(1):9

Hardy OJ, Vekemans X (1999) Isolation by distance in a continuous population: reconciliation between spatial autocorrelation analysis and population genetics models. Heredity 83:145–154

Hardy OJ, Vekemans X (2002) SPAGeDi: a versatile computer program to analyse spatial genetic structure at the individual or population levels. Mol Ecol Notes 2:618–620

Hastings A (1983) Can spatial variation alone lead to selection for dispersal? Theor Popul Biol 24:244–251

Hedin J, Ranius T (2002) Using radio telemetry to study dispersal of the beetle Osmoderma eremita, an inhabitant of tree hollows. Comput Electron Agric 35:171–180

Hedin J, Ranius T, Nilsson SG, Smith HG (2008) Restricted dispersal in a flying beetle assessed by telemetry. Biodivers Conserv 17:675–684

Holt RD (1985) Population dynamics in two-patch environments: some anomalous consequences of an optimal habitat distribution. Theor Popul Biol 28:181–208

IUCN (2003) Guidelines for application of IUCN red list criteria at regional levels: version 3.0. IUCN Species Survival Commission. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK, ii + 26 pp

Jäch MA et al (1994) Rote Liste der gefährdeten Käfer Österreichs (Coleoptera). In: Gepp J et al (eds) Rote Listen gefährdeter Tiere Österreichs, vol 2. Moser, Graz, pp 107–200

Johnson CA, Fryxell JM, Thompson ID, Baker JA (2009) Mortality risk increases with natal dispersal distance in American martens. Proc R Soc B 276:3361–3367

Jonsson M, Johannesen J, Seitz A (2003) Comparative genetic structure of the threatened tenebrionid beetle Oplocephala haemorrhoidalis and its common relative Bolitophagus reticulates. J Insect Conserv 7:111–124

Lange K (1997) Mathematical and statistical methods for genetic analysis. Springer, New-York

Larsson MC, Svensson GP (2009) Pheromones for monitoring rare and threatened insects: exploiting a pheromone-kairomone system to estimate prey and predator abundance. Cons Biol 23:1516–1525

Larsson MC, Hedin J, Svensson GP, Tolasch T, Francke W (2003) Characteristic odor of Osmoderma eremita identified as a male-released pheromone. J Chem Ecol 29:575–587

Levin SA, Cohen D, Hastings A (1984) Dispersal strategies in patchy environments. Theor Popul Biol 26:165–191

Mantel N (1967) The detection of disease clustering and a generalized regression approach. Cancer Res 27:209–220

Mokrzycki T, Byk A, Borowski J (2008) Rzadkie i reliktowe saproksyliczne chrząszcze (Coleoptera) starych dębów Rogalińskiego Parku Krajobrazowego [Rare and relict saproxylic beetles (Coleoptera) of old oaks of the Rogalin Landscape Park]. Parki Narodowe i Rezerwaty Przyrody 27:43–56 (In Polish, English summary)

Nieto A, Alexander KNA (2010) European red list of saproxylic beetles. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg

Nilsson SG, Baranowski R (1997) Habitat predictability and the occurrence of wood beetles in old-growth beech forests. Ecography 20:491–498

Nilsson SG, Baranowski R, Hedin J, Jansson N, Ranius T (2002) Hålträdslevande guldbaggars (Coleoptera, Scarabaeidae) biologi och utbredning i Sverige. Entomol Tidskr 123:81–97

Oddou-Muratorio S, Bontemps A, Klein EK, Chybicki I, Vendramin GG, Suyama Y (2010) Comparison of direct and indirect genetic methods for estimating seed and pollen dispersal in Fagus sylvatica and Fagus crenata. For Ecol Manag. doi:10.1016/j.foreco.2010.03.001

O’Grady JJ, Brook BW, Reed DH, Ballou JD, Tonkyn DW, Frankham R (2006) Realistic levels of inbreeding depression strongly affect extinction risk in wild populations. Biol Conserv 133:42–51

Oleksa A (2009) Conservation and ecology of the hermit beetle Osmoderma eremita s.l. in Poland. In: Buse J, Alexander KNA, Ranius T, Assmann T (eds) Saproxylic Beetles—their role and diversity in European woodland and tree habitats. Proceedings of the 5th symposium and workshop on the conservation of saproxylic beetles. Pensoft Series Faunistica 89:177–188

Oleksa A, Gawroński R (2006) Forest insects in an agricultural landscape—presence of old trees is more important than the existence of nearby forest. Ecol Quest 7:29–36

Oleksa A, Ulrich W, Gawroński R (2006) Occurrence of the mar bled rose-chafer (Protaetia lugubris Herbst, Coleoptera, Cetoniidae) in rural avenues in northern Poland. J Insect Conserv 10:241–247

Oleksa A, Ulrich W, Gawroński R (2007) Host tree preferences of hermit beetles (Osmoderma eremita Scop, Coleoptera) in a network of rural avenues in Poland. Pol J Ecol 55:315–323

Perrin N, Goudet J (2001) Inbreeding, kinship, and the evolution of natal dispersal. In: Clobert J, Danchin E, Dhondt AA, Nichols JD (eds) Dispersal. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 123–142

Płoski A (2009) Droga i jej otoczenia—świadectwo przemian historycznych na Warmii i Mazurach [Road and its surrounding—a witness to the historical changes in Warmia and Masuria]. In: Worobiec K, Liżewska I (eds) Aleje przydrożne—historia, znaczenie, zagrożenie, ochronia [Avenues—history, importance, threat and protection]. Borussia, Olsztyn, pp 71–91 (in Polish)

Prugnolle F, de Meeu T (2002) Inferring sex-biased dispersal from population genetic tools: a review. Heredity 88:161–165

Ranius T (2006) Measuring the dispersal of saproxylic insects: a key characteristic for their conservation. Popul Ecol 48:177–188

Ranius T, Douwes P (2002) Genetic structure of two pseudoscorpion species living in tree hollows in Sweden. Anim Biodiv Conserv 25(2):67–75

Ranius T, Hedin J (2001) The dispersal rate of a beetle, Osmoderma eremita, living in tree hollows. Oecologia 126:363–370

Ranius T, Nilsson SG (1997) Habitat of Osmoderma eremita Scop. (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae), a beetle living in hollow trees. J Insect Conserv 1:193–204

Ranius T, Aguado LO, Antonsson K, Audisio P, Ballerio A, Carpaneto GM, Chobot K, Gjurašin B, Hanssen O, Huijbregts H, Lakatos F, Martin O, Neculiseanu Z, Nikitsky NB, Paill W, Pirnat A, Rizun V, Ruicănescu A, Stegner J, Süda I, Szwałko P, Tamutis V, Telnov D, Tsinkevich V, Versteirt V, Vignon V, Vögeli M, Zach P (2005) Osmoderma eremita (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae: Cetoniinae) in Europe. Anim Biodiv Conserv 28:1–44

Ranius T, Niklasson M, Berg N (2009) Development of tree hollows in pedunculate oak (Quercus robur). For Ecol Manag 257:303–310

Roff DA (1975) Population stability and the evolution of dispersal in a heterogeneous environment. Oecologia 19:217–237

Rousset F (1997) Genetics differentiation and estimation of gene flow from F-statistics under isolation by distance. Genetics 145:1219–1228

Rousset F (2000) Genetic differentiation between individuals. J Evol Biol 13:58–62

Rousset F (2001) Genetic approaches to the estimation of dispersal rates. In: Clobert J, Danchin E, Dhondt AA, Nichols JD (eds) Dispersal. Oxford Univ. Press, New York, pp 18–28

Sagvik J, Uller T, Olsson M (2005) Outbreeding depression in the common frog, Rana temporaria. Conserv Genet 6:205–211

Schmuki C, Vorburger C, Runciman D, MacEachern S, Sunnucks P (2006) When log-dwellers meet loggers: impacts of forest fragmentation on two endemic log-dwelling beetles in south-eastern Australia. Mol Ecol 15:1481–1492

Schwartz MK, McKelvey KS (2009) Why sampling scheme matters: the effect of sampling scheme on landscape genetic results. Conserv Genet 10:441–452

Sedgeley JA (2001) Quality of cavity microclimate as a factor influencing selection of maternity roosts by a tree-dwelling bat, Chalinolobus tuberculatus, in New Zealand. J Appl Ecol 38:425–438

Slatkin M (1993) Isolation by distance in equilibrium and nonequilibrium populations. Evolution 47:264–279

Slatkin M (1995) A measure of population subdivision based on microsatellite allele frequencies. Genetics 139:457–462

Soto A, Lorenzo Z, Gil L (2007) Differences in fine-scale genetic structure and dispersal in Quercus ilex L. and Q. suber L.: consequences for regeneration of Mediterranean open woods. Heredity 99:601–607

Speight MCD (1989) Saproxylic invertebrates and their conservation. Council of Europe, Strasbourg

Svensson GP, Oleksa A, Gawroński R, Lassance J-M, Larsson MC (2009) Enantiomeric conservation of the male-produced sex pheromone facilitates monitoring of threatened European hermit beetles (Osmoderma sp.). Entomol Exp Appl 133(3):276–282

Svensson GP, Sahlin U, Brage B, Larsson MC (2011) Should I stay or should I go? Modelling dispersal strategies in saproxylic insects based on pheromone capture and radio telemetry: a case study on the threatened hermit beetle Osmoderma eremita. Biodivers Conserv 20:2883–2902

Travis JMJ, Dytham C (1998) The evolution of dispersal in a metapopulation: a spatially explicit, individual-based model. Proc Biol Sci 265:17–23

Travis JMJ, Dytham C (1999) Habitat characteristics and the evolution of dispersal. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 266:723–728

Vekemans X, Hardy OJ (2004) New insights from fine-scale spatial genetic structure analyses in plant populations. Mol Ecol 13:921–935

Vekemans X, Beauwens T, Lemaire M, Roldan-Ruiz I (2002) Data from amplified fragment length polymorphism (AFLP) markers show indication of size homoplasy and of a relationship between degree of homoplasy and fragment size. Mol Ecol 11:131–151

Vogl C, Karhu A, Moran G, Savolainen O (2002) High resolution analysis of mating systems: inbreeding in natural populations of Pinus radiata. J Evol Biol 15:433–439

Vos P, Hogers R, Bleeker M, et al. (1995) AFLP: a new technique for DNA fingerprinting. Nucleic Acids Res 23:4407–4414

Waples RS (2002) Definition and estimation of effective population size in the conservation of endangered species. In: Bessinger SR, McCullough DR (eds) Population viability analysis. University Chicago Press, Chicago, IL, pp 147–168

Watts PC, Rousset F, Saccheri IJ, Leblois R, Kemp SJ, Thompson DJ (2007) Compatible genetic and ecological estimates of dispersal rates in insect (Coenagrion mercuriale: Odonata: Zygoptera) populations: analysis of ‘neighbourhood size’ using a more precise estimator. Mol Ecol 16:737–751

Whitlock R, Hipperson H, Mannarelli M, Butlin RK, Burke T (2008) An objective, rapid and reproducible method for scoring AFLP peak-height data that minimizes genotyping error. Mol Ecol Res 8:725–735

Wiens JA (2001) The landscape context of dispersal. In: Clobert J, Danchin E, Dhondt AA, Nichols JD (eds) Dispersal. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 96–109

With KA, King AW (1999) Dispersal success on fractal landscapes: a consequence of lacunarity thresholds. Landscape Ecol 14:73–82

Wright S (1931) Evolution in Mendelian populations. Genetics 16:97–159

Wright S (1943) Isolation by distance. Genetics 28:114–138

Zayed A, Packer L, Grixti JC, Ruz L, Owen RE, Toro H (2005) Increased genetic differentiation in a specialist versus a generalist bee: implications for conservation. Conserv Genet 6:1017–1026

Zhivotovsky LA (1999) Estimating population structure in diploids with multilocus dominant DNA markers. Mol Ecol 8:907–913

Acknowledgments

This study was founded by the research grant from Polish Ministry of Science and The Higher Education (N N304 4175 33to AO). Because hermit beetles are under strict species protection in Poland, the study was undertaken based on the specific permission from Polish Ministry of Environment. The authors would like to thank Katarzyna Kowalkowska and Ewa Sztupecka for their laboratory work, and Daniel Doktór, Jean-Marc Lassance and Konrad H. Maciejewski for their assistance in the field.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Oleksa, A., Chybicki, I.J., Gawroński, R. et al. Isolation by distance in saproxylic beetles may increase with niche specialization. J Insect Conserv 17, 219–233 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-012-9499-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-012-9499-7