Abstract

How much are people willing to forego to be honest, to follow the rules? When people do break the rules, what can standard data sources tell us about their behavior? Standard economic models of crime typically assume that individuals are indifferent to dishonesty, so that they will cheat or lie as long as the expected pecuniary benefits exceed the expected costs of being caught and punished. We investigate this presumption by studying the response to a change in tax reporting rules that made it much more difficult for taxpayers to evade taxes by inappropriately claiming additional dependents. The policy reform induced a substantial reduction in the number of dependents claimed, which indicates that many filers had been cheating before the reform. Yet, the number of filers who availed themselves of this evasion opportunity is dwarfed by the number of filers who passed up substantial tax savings by not claiming extra dependents. By declining the opportunity to cheat, these taxpayers reveal information about their willingness to pay to be honest. In our analysis, we develop a novel method for inferring the characteristics of taxpayers in the absence of audit data. Our findings indicate both that this willingness to pay to be honest is large on average and that it varies significantly across the population of taxpayers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

A number of studies using audit data have tested for differences in evasion across income categories, gender, and tax rates (Clotfelter 1983; Feinstein 1991; Christian 1994). These articles do not, however, indicate whether these evasion differences are due to different opportunities to evade or different propensities conditional on opportunity. Our case study has the advantage of being an opportunity that is readily available to all taxpayers, which allows us to isolate evasion predilection.

For a thorough discussion and critique of the literature, see Andreoni et al. (1998) and Slemrod (2007). Of particular interest to our work is the finding from laboratory studies that some people comply with the tax authority, even when the probability of audit is known to be zero, which implies a desire to be honest (Baldry 1987; Alm et al. 1992).

Today more than 90 % of SSNs issued to children are issued at the time of birth, through the Enumeration at Birth program, which began in 1989 (GAO 2005).

Recent research on dependent overclaiming focuses on the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). McCubbin (2000) describes data from a 1994 audit of randomly selected EITC claimants. Approximately 26 % of EITC dollars claimed were overturned upon audit, and about 70 % of these overclaims involved an error in claiming an EITC-qualifying child. McCubbin further finds that misclaiming a child is sensitive to the size of the associated benefit. She estimates that a $100 increase in the tax savings from claiming a child increases the probability of erroneously claiming an EITC-qualifying child from a mean of 8 % to 8.4 %. Liebman (2000) estimates the extent of EITC misclaiming by matching March 1991 CPS respondents to 1990 tax return data. At the time, the EITC was exclusively available to filers with children. Liebman estimates that 11 to 13 % of 1990 EITC recipients did not have a child in their CPS household as of March 1991, and 10 % did not have a child in the household one year earlier.

See Whittington and Peters (1996) for evidence that the tax effect on this decision is small.

For returns with adjusted gross income (AGI) greater than $200,000, the number of exemptions for children living at home is topcoded at 3. This topcoding is unlikely to affect our results, as only 7 filing units observed in both 1986 and 1987 are affected. The number of filing units affected in any other pair of years over which dependent loss is calculated is never greater than 22.

Because children are more likely to live with unmarried mothers than unmarried fathers, estimates of the total number of dependents from the tax panel are somewhat lower than the total number of dependents appearing in cross-sections of tax return data. This gap is visible in Fig. 3 below.

There are other cases in which requiring a taxpayer to provide a straightforward piece of supporting evidence has generated a large change in reporting. Fack and Landais (2011) show that when France first required that receipts for charitable contributions be submitted with tax returns, reported charitable contributions fell by 75 %.

Note that the shares losing and gaining dependents are calculated with different bases in Fig. 2. All filers observed in two consecutive years are included when computing the share of filers gaining a dependent. Only filers observed in two consecutive years and claiming a dependent in the first year are included when computing the share losing a dependent. If we compute the share losing a dependent without conditioning on previously claiming one, 1987 still stands out. About 8 % of filing units lose a dependent in 1987, compared to 5 to 6 % in all other years.

The previous figure includes all dependents claimed, regardless of their relationship to the filer. This figure considers only dependents who are children of filers. Children account for 95 % of all dependents claimed. All returns observed in the OTPR panel in a given year are used to estimate the total number of child dependents, with different weights across years to account for the fluctuations in sample size.

We thank Brian Erard for providing us with the publication 1304 data. Despite the small size of the OTPR panel, the values we impute from it are a close match to values computed from aggregate data.

The slight increase over time in both series is consistent with rising college enrollment rates, which enables more children between 19 and 24 to be claimed. Data from the National Center for Education Statistics (1995) show that the college enrollment rate of 18- to 24-year olds increased from 25 % in 1979 to 28 % in 1986.

Using a fake SSN may have been a viable strategy because the IRS, lacking resources, only computer matched 3 % of SSNs in the years just after the change (General Accounting Office 1993).

There is a noticeable uptick in SSN applications in 1983. This is the first year in which recipients of interest and dividend payments needed to provide an SSN to the financial institution issuing these payments (Long 1993). Parents who had established savings accounts in the names of their children would have needed SSNs for their children at this point.

Because underlying fluctuations in the sample may be affecting the patterns we observe, we have constructed a balanced-panel version of Fig. 5 that includes only those filing units observed in all years of the panel. This alternative figure is quite similar; it too shows that the group of filers who lose dependents in 1987 is not particularly likely to gain dependents in subsequent years.

This may result in part from changes in who is claiming dependents following marital changes. In cases where a filing unit loses a dependent and gains a dependent in the following year, 25.3 % transitioned out of married filing jointly status at some earlier point in the panel. Among filing units losing a dependent in one year and not subsequently regaining, only 14.7 % had previously transitioned out of married filing jointly status.

In the extreme case where cheaters have a zero chance of regaining a dependent, however, we would expect to see an even lower rate of regaining for 1987 dependent losers, given that nearly one-third of this group are estimated to be cheaters. This suggests that there could be modestly higher than average regaining rates among honest filers who lost a dependent in 1987.

A caveat here is that households may fail to minimize taxes in this manner under models of intrahousehold bargaining that lead to inefficiencies. A unitary household model, a model that results in efficient bargaining, or one that includes transferable utility will result in tax minimization because these models predict that families will maximize welfare and then bargain over the surplus.

The TAXSIM program is described by Feenberg and Coutts (1993).

We use the CPI-U all items, which was 109.6 in 1986 and almost exactly double, 218.1, in 2010.

If filers are cheating on other margins, this creates background risk, which will have a small effect on our calculations. The effect is small because this other risk is born whether the individual decides to claim a false dependent or not. So long as the probability of audit is not a function of claiming a false dependent (which is likely because so many people claim dependents that this cannot be a useful audit criterion), our simplification is an important restriction only if falsely claiming a dependent makes other cheating easier to detect, conditional on audit.

Estimates of the coefficient of relative risk aversion based on observed equity return premiums are in the neighborhood of 50 (DeLong and Magin 2009). Even numbers in this range have almost no impact on our estimates.

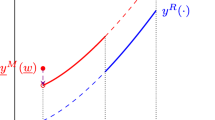

In principle, estimates of the distribution of the willingness to pay to be honest could be estimated by comparing the amount of cheating at different tax values, given an additional assumption about the joint distribution of ΔT and θ. We pursued this empirical strategy but determined that the available tax panel data are of insufficient sample size given the observed variation in tax values to produce meaningful estimates.

Assuming that all 1986 dependent losers are honest ignores any anticipatory changes in dependent claiming behavior. This will be problematic if some individuals gave up improper dependent claiming in the year the SSN requirement was announced rather than in the following year when it was implemented. We have addressed this concern by instead using the filing units losing dependents in 1985 to estimate means for honest dependent losers. The results of this analysis are quite similar to what we report in columns 1 and 3 of Table 4.

The IRS began requiring a Social Security number or taxpayer identification number for the care provider for anyone claiming the child care credit in 1989. As discussed in O’Neil and Lanese (1993) and cited by Slemrod and Bakija (2008, pp. 238–239), this reform was followed by a substantial increase in the number of claims of self-employment income; a response similar in spirit to what we analyze here.

We have also replicated the comparisons in columns 1 and 2 of Table 4 for every other year in our sample, as a placebo test. Overall, we find that there are 21 cases where the adjacent year means are statistically different at the 10 % level, out of 137 pairwise comparisons. In only one other year (1982) is there a statistical difference in the percentage of married filers, and in only two (1982 and 1989) is there a difference in share of head of household filers. Thus, we do reject equality more often than would be predicted by pure sampling variation, but the rejection is not concentrated in our variables of interest, and we believe that other tax reforms in other years will cause some statistics to differ. There are a number of significant differences between the groups of filers losing dependents in 1982 and in each of the adjacent years. We suspect this reflects the tax reform act that took effect in 1982. There are four significant differences in the IRA contribution variable, likely reflecting changes in IRA contribution rules.

We are especially grateful to Damon Jones for suggesting this approach.

An assumption about exactly how many cheaters were in each group in 1986 is still required because this influences the denominator in the calculations. We assume that no one losing a dependent in 1986 is a cheater, and that no one gaining a dependent in 1987 is a cheater. Modifying these assumptions has a very modest impact on our estimates.

We have calculated parallel comparisons that compare 1987 to pooled means across 1980–1986, which has the advantage of increasing the sample size. Most of our findings are robust to this change in comparison group, but the difference between the two methodologies is inflated for several characteristics, including claiming of the child care credit, itemizing, and IRA contributions. This may not be surprising, however, because there are other changes in the tax code in that time period which make assumptions about stability of means across different time periods much stronger than in the 2-year comparison.

Note that this setup assumes relatively little variation in risk preferences and the probability of audit. Because risk has little impact on the valuation of evasion, this portion of the assumption is innocuous, but if there is substantial heterogeneity in the subjective probability assigned to being audited, then this could also play a significant role in explaining the decision to evade.

References

Allingham, M. G., & Sandmo, A. (1972). Income tax evasion: a theoretical analysis. Journal of Public Economics, 1, 323–338.

Alm, J., McClelland, G. H., & Schulze, W. D. (1992). Why do people pay taxes? Journal of Public Economics, 48, 21–38.

Andreoni, J., Erard, B., & Feinstein, J. (1998). Tax compliance. Journal of Economic Literature, 36(2), 818–860.

Attanasio, O. P., & Paiella, M. (2011). Intertemporal consumption choices, transaction costs and limited participation in financial markets: reconciling data and theory. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 26(2), 322–343.

Auten, G., & Carroll, R. (1999). The effect of income taxes on household income. Review of Economics and Statistics, 81(4), 681–693.

Baldry, J. (1987). Income tax evasion and the tax schedule: some experimental results. Public Finance, 42(3), 357–383.

Becker, G. S. (1968). Crime and punishment: an economic approach. Journal of Political Economy, 76(2), 169–217.

Becker, W., Büchner, H.-J., & Sleeking, S. (1987). The impact of public transfer expenditures on tax evasion. Journal of Public Economics, 34, 243–252.

Block, M. K., & Heineke, J. M. (1975). A labor theoretic analysis of the criminal choice. American Economic Review, 65(3), 314–325.

Bordignon, M. (1993). A fairness approach to income tax evasion. Journal of Public Economics, 52, 345–362.

Chetty, R. (2006). A new method of estimating risk aversion. American Economic Review, 96(5), 1821–1834.

Christian, C. W. (1994). Voluntary compliance with the individual income tax: results form the 1988 TCMP study. In IRS research bulletin 1993/1994, publication 1500 (Rev. 9–94).

Christian, C. W., & Frischmann, P. J. (1989). Attrition in the statistics of income panel of individual returns. National Tax Journal, 42(4), 495–501.

Clotfelter, C. T. (1983). Tax evasion and tax rates: an analysis of individual returns. Review of Economics and Statistics, 65(3), 363–373.

Cowell, F. A. (1992). Tax evasion and inequity. Journal of Economic Psychology, 13, 521–543.

Crump, R., Goda, G. S., & Mumford, K. (2011). Fertility and the personal exemption: comment. American Economic Review, 101(4), 1616–1628.

DeLong, J. B., & Magin, K. (2009). The US equity return premium: past, present, and future. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23(1), 193–208.

Dickert-Conlin, S., & Chandra, A. (1999). Taxes and the timing of births. Journal of Political Economy, 107(1), 161–177.

Dubin, J. A., Graetz, M. J., & Wilde, L. (1990). The effect of audit rates on the federal individual income tax, 1977–1986. National Tax Journal, 43(4), 395–409.

Erard, B., & Feinstein, J. S. (1994). Honesty and evasion in the tax compliance game. Rand Journal of Economics, 25(1), 1–19.

Fack, G., & Landais, C. (2011). Charitable giving and tax policy in the presence of tax cheating: theory and evidence from the US and France. Manuscript: Stanford University.

Feenberg, D., & Coutts, E. (1993). An introduction to the TAXSIM model. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 12(1), 189–194.

Feinstein, J. S. (1991). An econometric analysis of income tax evasion and its detection. Rand Journal of Economics, 22(1), 233–276.

Feldman, N. E., & Slemrod, J. (2007). Estimating tax noncompliance with evidence from unaudited tax returns. Economic Journal, 117, 327–352.

Fisman, R., & Wei, S.-J. (2004). Tax rates and tax evasion: evidence from “missing imports” in China. Journal of Political Economy, 112(2), 843–877.

General Accounting Office (1993). Erroneous dependent and filing status claims. GAO/GGD-93-60.

General Accounting Office (1996). Audit trends and results for individual taxpayers. GAO/GGD-96-61.

Gordon, J. P. F. (1989). Individual morality and reputation costs as deterrents to tax evasion. European Economic Review, 33, 797–805.

Gruber, J. (2009). Public finance and public policy (3rd ed.). New York: Worth.

Holtzblatt, J., & McCubbin, J. (2003). Whose child is it anyway? Simplifying the definition of a child. National Tax Journal, 56(3), 701–718.

Internal Revenue Service Oversight Board (2011). 2010 taxpayer attitude survey. US Department of the Treasury January 2011.

Jacob, B. A., & Levitt, S. D. (2003). Rotten apples: an investigation of the prevalence and predictors of teacher cheating. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(3), 843–877.

Jones, D. (2012) Inertia and overwithholding: explaining the prevalence of income tax refunds. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 4(1), 158–185.

Klepper, S., & Nagin, D. (1989). The anatomy of tax evasion. Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization, 5(1), 1–24.

Kleven, H. J., Knudsen, M. B., Kreiner, C. T., Pederson, S., & Saez, E. (2011). Unwilling or unable to cheat? Evidence from a randomized tax audit experiment in Denmark. Econometrica, 79(3), 651–692.

Levitt, S. D., & Dubner, S. J. (2005). Freakonomics. New York: Harper Collins.

Liebman, J. B. (2000). Who are the ineligible EITC recipients? National Tax Journal, 53(4), 1165–1185.

Long, W. S. (1993). Social security numbers issued: a 20-year review. Social Security Bulletin, 56(1), 83–86.

Los Angeles Times (1987). IRS mails data on new tax code, October 14.

McCubbin, J. (2000). EITC noncompliance: the determinants of the misreporting of children. National Tax Journal, 53(4), 1135–1164.

National Center for Education Statistics (1995). Digest of education statistics. US Department of Education.

New York Amsterdam News (1988). Tax returns require SSNs for dependents, March 5.

Oliva, P. (2010). Environmental regulations and corruption: automobile emissions in Mexico city. Manuscript. Santa Barbara: University of California.

O’Neil, C. J., & Lanese, K. B. (1993). T.I.N. requirements and the child care credit: impact on taxpayer behavior. Manuscript, University of South Florida.

Phillips, M. D. (2010). Taxpayer response to targeted audit. Manuscript, University of Chicago.

Pissarides, C. A., & Weber, G. (1989). An expenditure-based estimate of Britain’s black economy. Journal of Public Economics, 39, 17–32.

Slemrod, J. (1992). Taxation and inequality: a time-exposure perspective. Tax Policy and the Economy, 6, 105–128.

Slemrod, J. (2007). Cheating ourselves: the economics of tax evasion. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21(1), 25–48.

Slemrod, J., & Bakija, J. (2008). Taxing ourselves: a citizen’s guide to the debate over taxes (4h ed.). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Slemrod, J., & Weber, C. (2012). Evidence of the invisible: towards a credibility revolution in the empirical analysis of tax evasion and the informal economy. International Tax and Public Finance, 19(1), 25–53.

Smith, K. W. (1992). Reciprocity and fairness: positive incentives for tax compliance. In Why people pay taxes (pp. 223–250). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Spicer, M. W., & Becker, L. A. (1980). Fiscal inequality and tax evasion: an experimental approach. National Tax Journal, 33(2), 171–175.

Szilagyi, J. A. (1990). Where have all the dependents gone? In Internal revenue service publication (IRS): Vol. 1500. Trend analyses and related statistics—1990 update (pp. 63–72).

Tyler, T. R. (1990). Why people obey the law. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Whittington, L. A., & Peters, H. E. (1996). Economic incentives for financial and residential independence. Demography, 33(1), 82–97.

Whittington, L. A., Alm, J., & Peters, H. E. (1990). Fertility and the personal exemption: implicit pronatalist policy in the united states. American Economic Review, 80(3), 545–556.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Jon Bakija, Brian Erard, Naomi Feldman, Bill Gentry, Jens Ludwig, Damon Jones, Lucie Schmidt, Joel Slemrod and seminar participants at the National Tax Association and Universidad de Chile for helpful comments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

LaLumia, S., Sallee, J.M. The value of honesty: empirical estimates from the case of the missing children. Int Tax Public Finance 20, 192–224 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-012-9221-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10797-012-9221-4