Abstract

Anaerobic ammonium oxidizing (anammox) bacterial community structures were investigated in surface (1–2 cm) and lower (20–21 cm) layers of mangrove sediments at sites located immediately to the mangrove trees (S0), 10 m (S1) and 1000 m (S2) away from mangrove trees in a polluted area of the Pearl River Delta. At S0, both 16S rRNA and hydrazine oxidoreductase (HZO) encoding genes of anammox bacteria showed high diversity in lower layer sediments, but they were not detectable in lower layer sediments in mangrove forest. S1 and S2 shared similar anammox bacteria communities in both surface and lower layers, which were quite different from that of S0. At all three locations, higher richness of anammox bacteria was detected in the surface layer than the lower layer; 16S rRNA genes revealed anammox bacteria were composed by four phylogenetic clusters affiliated with the “Scalindua” genus, and one group related to the potential anammox bacteria; while the hzo genes showed that in addition to sequences related to the “Scalindua”, sequences affiliated with genera of “Kuenenia”, “Brocadia”, and “Jettenia” were also detected in mangrove sediments. Furthermore, hzo gene abundances decreased from 36.5 × 104 to 11.0 × 104 copies/gram dry sediment in lower layer sediments while increased from below detection limit to 31.5 × 104 copies/gram dry sediment in lower layer sediments from S0 to S2. The results indicated that anammox bacteria communities might be strongly influenced by mangrove trees. In addition, the correlation analysis showed the redox potential and the molar ratio of ammonium to nitrite in sediments might be important factors affecting the diversity and distribution of anammox bacteria in mangrove sediments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) is a microbial nitrogen transformation process that allows ammonium to be oxidized by nitrite under anoxic conditions (van de Graaf et al. 1995). The observations from both field and laboratory investigations have indicated that anammox is a key process in the global nitrogen cycle (Devol 2003; Francis et al. 2007). Anammox has been demonstrated in very diverse environments, including the suboxic zone of the Black Sea (Kuypers et al. 2003), oxygen minimum zones (OMZ) at Namibian coast and Arabian Sea (Kuypers et al. 2005; Ward et al. 2009), and a number of temperate estuarine, coastal and offshore sediments (Thamdrup and Dalsgaard 2002; Jetten et al. 2003; Risgaard-Petersen et al. 2004; Tal et al. 2005; Trimmer et al. 2005; Rich et al. 2008), lakes (Schubert et al. 2006), freshwaters (Penton et al. 2006), polar region sediments and multiyear sea ice (Rysgaard and Glud 2004; Rysgaard et al. 2004), and deep sea hydrothermal vent (Byrne et al. 2009). Anammox microorganisms are monophyletic members of the phylum Planctomycetes (Strous et al. 1999; Schmid et al. 2005), including Candidatus “Brocadia”, Candidatus “Kuenenia”, Candidatus “Anammoxoglobus”, Candidatus “Scalindua” and Candidatus “Jettenia” (Schmid et al. 2005; Kartal et al. 2007, 2008; Kuenen 2008; Quan et al. 2008).

While most available knowledge about anammox bacteria diversity was based on the 16S rRNA gene sequences, the hydrazine oxidoreductase (HZO), a key protein that dehydrogenated the unique anammox intermediate, hydrazine, to dinitrogen gas, was considered as a new biomarker for anammox bacteria recently (Schalk et al. 2000; Shimamura et al. 2007; Klotz and Stein 2008). Since hzo genes are definitively and specifically linked to anammox reaction, analysis of hzo genes diversity, abundance and expression in the environment could obviously provide a more comprehensive understanding about anammox bacteria. Several specific primers have been designed to amplify hzo genes from various environments, which further confirmed the hzo gene as a suitable target for molecular ecological studies on anammox bacteria (Schmid et al. 2008). Recently, a new PCR primer set was also used to detect hzo genes in various marine sediments and results indicated that anammox hzo genes were broadly distributed in marine environments with a high diversity related to the anthropogenic import (Li et al. 2010). However, there are only few reports using hzo genes as biomarkers to investigate anammox bacteria diversity (Quan et al. 2008; Schmid et al. 2008; Li et al. 2009). Thus, there is an urgent need for analysis of anammox bacteria in a wider range of natural ecosystems based on hzo genes, a new tool to study anammox bacteria in natural ecosystems.

One major component of the tropical and subtropical coastal wetlands is mangrove ecosystem, which occupies the intertidal zone of estuaries, bays, inlets and gulfs and part of the riparian zone (Alongi 2002). Mangrove ecosystems play an important role as refuge, feeding, and breeding ground for many organisms and sustain an extensive food web based on detritus (Holguin et al. 2001). In mangrove ecosystems, microbial nitrogen processes, including dinitrogen (N2)-fixation, nitrification, denitrification, ammonification, anammox and dissimilatory nitrate reduction to ammonium, form a complex microbial nitrogen transformation (Purvaja et al. 2008). Among these processes, nitrogen fixation occurred in the rhizosphere of mangrove trees, decomposing leaves, and aerial roots and bark (Alongi 2002), while nitrification (Kristensen et al. 1998) and denitrification (Rivera-Monroy 1996) were also widely recorded in mangrove sediment since the regular tide provided an alternating aerobic and anaerobic conditions. Isotope technique had been used to detect the activity of anammox in the mangroves of Logan and Albert River system contributing 0–9% of the sediment N2 production, which is the first evidence for the participation of anammox bacteria in nitrogen transformation in the mangrove ecosystem (Meyer et al. 2005). However, comparing to the other nitrogen microbial process, previous studies only provided limited information on the anammox process; as a result, the diversity, distribution and abundances of anammox bacteria in mangrove ecosystem are still unknown.

In the present study, we selected Mai Po Nature Reserve of Hong Kong, the largest mangrove wetland in the Southern China as our research area to investigate the anammox bacteria diversity, spatial distribution and abundance using both 16S rRNA and hzo genes. Environmental parameters were also analyzed to identify their influences on the anammox bacteria community structure and abundances in the mangrove sediments. The results of present study allowed us to more clearly understand the anammox bacteria in the mangrove ecosystem.

Materials and methods

Sampling and chemical analysis

Mai Po Marshes Nature Reserve, located at the northwestern corner of the New Territories of Hong Kong (22°30′ N, 114°02′ E) in the greater Pearl River Delta, is the largest remaining coastal wetland in Hong Kong. Mai Po comprises of sub-tropical mangroves, inter-tidal mudflats, as well as man-made fishponds and drainage channels. In the mangrove wetland, the dominated mangrove forests are Kandelia obovata (formerly known as Kandelia candel). Three sampling sites (S0, S1, and S2) were selected in a transect: the location of site S0 was immediately to the mangrove trees while site S1 with a distance of 10 m to the mangrove trees, and site S2 was at the inter-tidal mudflats about 1,000 m from S0 without any mangrove tree around. The surface layer (1–2 cm) and lower layer (20–21 cm) sediment samples were collected in triplicate at each of the three sampling sites at the same distance to mangrove trees, and all samples were immediately transferred into 4°C cooler for transport back to the laboratory for analyses (within 2 h).

Temperature, redox potential and pH of the sediment samples were measured in situ using IQ180G Bluetooth Multi-Parameter System (Hach Company, Loveland, CO) and concentration of NH4 +-N, NO3 −-N, and NO2 −-N in pore water of sediment samples, after centrifugation and collection, were measured with an autoanalyzer (QuickChem, Milwaukee, WI) according to standard methods by the American Public Health Association (American Public Health Association 1995). Salinity of pore water was measured using YSI 556 Multiprobe System (YSI, Yellow Springs, OH).

DNA extraction and PCR amplification

Total genomic DNA of each sediment sample was extracted using the SoilMaster DNA Extraction kit (Epicentre Biotechnologies, Madison, WI). PCR amplifications for 16S rRNA and hzo genes were performed according to the previous study with primer sets Brod541F-Amx820R (Schmid et al. 2000; Penton et al. 2006; Li et al. 2010) and hzocl1F11-hzoclR2 (Schmid et al. 2008), respectively. PCR products were checked by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gels and subsequent staining with ethidium bromide (0.5 μg ml−1).

Cloning, sequencing and phylogenetic analysis

PCR amplified products were purified using Gel Advance-Gel Extraction System (VIOGEME, Taipei) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, and cloned into the pMD 18 T-Vector (Takara, Japan). The insertion of an appropriate-sized DNA fragment was checked by PCR amplification with the primer set M13F and M13R. Different numbers of clones in each library were randomly selected for sequencing. Sequencing was performed with the Big Dye Terminate kit (Applied Sciences, Foster City, CA) and an ABI Prism 3730 DNA analyzer.

DNA sequences were examined and edited with MEGA 4.0 software (Tamura et al. 2007) and the chimera was checked using the Check Chimera program of the Ribosomal Database Project (Cole et al. 2005). For 16S rRNA gene, DNA sequences were aligned using the CLUSTAL W (Thompson et al. 1994). For hzo gene, DNA sequences were firstly translated into amino acids and the resulting protein sequences were aligned with referenced sequences. Phylogenetic trees were constructed by the neighbor-joining method, and bootstrap re-sampling analysis for 1,000 replicates was performed to estimate the confidence of the tree topologies.

Quantitative PCR assay

The copy numbers of hzo gene of anammox bacteria in all samples were determined in triplicate using an ABI 7000 Sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). The quantification was based on the fluorescent dye SYBR-Green I, which binds to double-stranded DNA during PCR amplification. Each reaction was performed in a 25 μl volume containing 2 μl of DNA template, 1 μl BSA (0.1%), 1 μl of each primer (20 μM, hzocl1F1 and hzocl1R2) and 12.5 μl of Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Bioshystems, Foster City, CA). The PCR cycle was started with 2 min at 50°C and 10 min at 95°C, followed by total of 48 cycles of 1 min at 95°C, 1 min at 50°C, and 1.5 min at 72°C. Standard plasmid carrying anammox hzo gene was generated by amplifying hzo gene from extracted DNA of site S1-s sediments and cloning into pMD 18 T-Vector (Takara, Japan). The copy numbers of target genes were calculated directly from the concentration of the extracted plasmid DNA. Ten-fold serial dilutions of a known copy number of the plasmid DNA were subjected to quantitative PCR assay in triplicate to generate an external standard curve. The Q-PCR amplification efficiencies ranged 0.85–0.92 (hzo), and correlation coefficients (r 2) were greater than 0.99.

Statistical analysis

Operational taxonomic units (OTUs) for community analysis were defined by a 2% cut-off in 16S rRNA gene nucleotide or HZO protein sequences, as determined by using the furthest neighbor algorithm in DOTUR (Schloss and Handelsman 2005). Shannon and Simpson indices of each clone library were also generated by DOTUR. To determine the significance of the difference between any of two clone libraries (e.g., X and Y), differences (ΔC) between “homologous” C X(D) and ‘‘heterologous’’ coverage curves C XY(D) were calculated using LIBSHUFF software version 0.96 (http://libshuff.mib.uga.edu/) according to the Singleton method (Singleton et al. 2001). The geographic distributions of anammox bacteria 16S rRNA and hzo genes were analyzed by the principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) and Jackknife Environment Clusters analysis as suggested previously (Lozupone et al. 2006). Meanwhile, Pearson correlation analysis between diversity and environmental variables was conducted using Microsoft Excel program. Meanwhile, Pearson correlation analysis between diversity and environmental variables was conducted using Microsoft Excel program.

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers

The GenBank accession numbers for the 16S rRNA gene sequences reported here are GQ331333 to GQ331362; and the GenBank accession numbers for the hzo gene sequences are GQ331363 to GQ331389.

Results

Biogeochemical characteristics of sampling sites

The biogeochemical characteristics of sampling sites, including temperature, redox, pH of sediments and nitrate, nitrite, ammonium and salinity of pore-water, are shown in Table 1. All surface layer samples for three sites showed a relatively higher redox potential, temperature and concentration of nitrate than the lower layer. However, the variations of nitrite, ammonium and pH between the surface and lower layer were quite different. In mangrove sediments (S0 and S1), surface layer samples have lower nitrite concentration but higher pH and concentration of ammonium compared to the low layer, where the concentration of ammonium in S0-l was only 250.0 μM, the lowest among all sampling sites. However, the variation trends of pH, nitrite, and ammonium concentrations were reversed in non-mangrove sediments (S2).

Phylogenetic diversity of anammox bacteria by 16S rRNA genes

All anammox-like 16S rRNA gene sequences obtained in the present study were divided into four clusters which fell deeply into Candidatus “Scalindua” clade, and the sequence similarity within each cluster was more than 97.0% (Fig. 1). In Cluster 1, 25 sequences recovered from sites S1-s and S2-s are closely related to the clones from river estuary sediments (Dale et al. 2009) and Candidatus “Scalindua wagneri” (Kuypers et al. 2003). Eight sequences from S0-s and S2-s established the Cluster 2, representing a novel cluster based on phylogenetic analysis. Cluster 3 was supported by the clones recovered from the surface sediment samples (S1-s and S0-s), and these clones were more affiliated with the 16S rRNA gene sequences of Candidatus “Scalindua brodae” and Candidatus “Scalindua arabica”. Cluster 4, the most common cluster containing 96 anammox-like sequences from all sediment samples (except S0-l), was the dominant anammox bacteria, which closely related to the clone recovered from Xinyi river sediment in China. Another interesting group Cluster P contained four sequences from site S1-l and was not clustered with any known anammox bacteria, but sequences in this cluster showed a high similarity (96.6–97.4%) with those detected from hydrothermal vent, where the activity and diversity of anammox bacteria were confirmed recently (Byrne et al. 2009), thus the cluster P might be considered as a potential anammox bacteria group.

Consensus phylogenetic tree constructed after subjecting to an alignment of anammox bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences from this study and those retrieved from database to neighbor-joining analysis. Numbers in parenthesis refer to the clone numbers retrieved by amplification with the primer set (Brod541F–Amx820R) and assigned to an individual phylotype. The numbers at the nodes are percentages that indicate the levels of bootstrap support based on 1,000 resampled data sets (only values greater than 50% are shown). Branch lengths correspond to sequence differences as indicated by the scale bar

Rarefaction analysis indicated that site S0-s had the greatest anammox-16S rRNA genes diversity while site S2-l (except S0-l) was the lowest. At the same time, the rarefaction analysis also showed the surface layer samples had higher diversity of OTUs than that of lower layer samples at each sampling site, consistent with the values of Simpson and Shannon indices (Fig. S-1A; Table 2). It was interesting that no anammox-like bacterial 16S rRNA gene sequences were detected in a total of 29 clones from site S0-l, where the low layer was the only one in the mangrove forest (Table 2).

Phylogenetic diversity of anammox bacteria by hzo genes

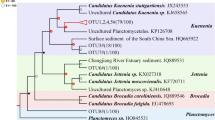

All hzo gene sequences recovered in the present study showed high similarity (>84% in protein sequences) with those published in previous studies. Phylogenetic analysis showed that recovered HZO sequences were grouped into five distinct sub-clusters, designated as Cluster 1-1, 1-2, 1-3, 1-4, and 1-5 shown in Fig. 2, within the recently proposed hzo Cluster 1 (Schmid et al. 2008). Sequences in Cluster 1-1 were closely related to HZO proteins from Uncultured planctomycete (ACF95877), the enrichment culture Candidatus “Kuenenia sp.” (CAQ57912), Candidatus “Brocadia sp.” enrichment culture (CAQ57910), and the two octaheme cytochrome c gene product present in the genome of Candidatus “Kuenenia stuttgartiensis” (CAJ72085 and CAJ71439). However, sequences in Clusters 1-2 were more closely related to the uncultured planctomycete HZO proteins CAQ57913 and CAQ57914 than ACF95877, CAQ57912, and CAQ57910. In addition, the deduced HZO protein sequences in Clusters 1-3, 1-4 and 1-5 were more closely affiliated to CAQ57913 and CAQ57914, as well as one sequence obtained from Candidatus “Scalindua sp.” (CAQ57909). The deduced HZO protein sequences in Cluster 1-3, Cluster 1-4, and Cluster 1-5 constituted sister clades with Cluster 1-2 which contained only sequences unique to our investigated area (Fig. 2).

Consensus phylogenetic tree constructed after subjecting to an alignment of deduced HZO protein sequences from this study and those retrieved from database to neighbor-joining analysis. Numbers in parenthesis refer to hzo gene clone numbers retrieved using the primer set (hzocl1F1-hzocl1R2) and assigned to an individual phylotype. The numbers at the nodes are percentages that indicate the levels of bootstrap support based on 1,000 resampled data sets (only values greater than 50% are shown). Branch lengths correspond to sequence differences as indicated by the scale bar. Major clades were named following a proposal of Schmid et al. (2008)

Rarefaction analysis showed the greatest hzo genes diversity occurred at site S0-s, and the lowest richness at site S2-l (except site S0-l, where no PCR amplicon could be obtained), consistent with the results of 16S rRNA gene (Fig. S-1B). Both Simpson and Shannon indices indicated a higher diversity in surface layer samples at each site, except the Shannon index in site S1 (Table 2).

Abundance of hzo gene of anammox bacteria in mangrove sediments

Except no hzo genes were detected at site S0-l, the obtained anammox hzo gene abundances ranged from 7.5 × 104 to 36.5 × 104 copies per gram of sediments (dry weight) (Fig. 3). The hzo gene determined at sites S1 and S0 showed a significant higher copy number in surface layer samples than lower layer samples (p < 0.05, n = 3). However, in site S2, the surface layer sample had a lower hzo gene copy number than the lower layer samples (p < 0.05, n = 3). Interestingly, hzo abundances decreased in surface layer from S0 to S2 along with the distance between sampling sites and mangrove trees, while increased in lower layer along with the same transect, showing a significant positive correlation (r = 0.98, n = 3) (Fig. 3).

Anammox bacterial community structure comparison and relationships with environmental factors

Based on the P-values calculated using LIBSHUFF software, there was little significant compositional overlap of anammox bacteria community structure in the five sediment samples (Table S-1). The 16S rRNA gene sequences showed no significant difference between S1-s and S2-s, or S1-l and S2-l, while statistical difference in the other two sites. For hzo gene, only S1-s vs. S2-s and S2-s vs. S2-l showed similar clone libraries composition. It was needed to point out that both 16S rRNA and hzo gene clone libraries at site S0-s were significantly different from the other sampling sites, indicating a special anammox bacterial community structure. As for the clone library comparison, PCoA and Jackknife Environment Clusters analyses of 16S rRNA and hzo genes showed that sites S1-s and S2-s shared quite similar anammox bacteria community structures; and lower layer samples (S1-l and S2-l) also shared similar community structures based on 16S rRNA gene though hzo genes at the two sites were not closely related to each other (Fig. 4). It was very interesting that the anammox bacterial community structure in S0-s, the only site in mangrove forest, formed a clearly distinct biogeographic cluster, separating from all other sites for the anammox bacterial structures. Furthermore, Pearson moment correlation analysis showed that the OTUs and Shannon index of 16S rRNA and hzo genes significantly correlated with redox potential of the sediments, and hzo gene abundances strongly correlated with the molar ratio of ammonium to nitrite, but no significant correlations were detected for the anammox diversity and abundances with other biogeochemical parameters (Table 3).

Dendrogram and PCoA based on the UniFrac metric of 16S rRNA gene (a) and deduced HZO protein (b) sequences on diversity of anammox bacteria, based on sequence abundance data. Circles in dendrogram trees represent Jackknife support for the monophyly at the node. Solid circles 90–99.9%; open circles 50–90%

Discussions

The phylogenetic diversity of anammox bacteria in the environments is studied based on the retrieved 16S rRNA gene sequences; however, specific 16S rRNA gene sequences belonging to the anammox group have historically been difficult to recover from environmental samples (Schmid et al. 2005; Penton et al. 2006). According to our previous results, we optimized a new primer combination (Brod541F-Amx820R) to detect anammox bacteria from various marine sediments, which showed higher specificity and efficiency than other primer sets (Li et al. 2010). Thus, using primer set Brod541F-Amx820R in the present study, results indicated multiple ecotypes of “Scalindua” genus anammox bacteria in mangrove sediments. However, from the phylogeny results of hzo gene, five sub-clusters of HZO sequences were found in mangrove sediment samples, which related not only to enrichment cultures of Candidatus “Scalindua sp.”, but also sequences related to Candidatus “Kuenenia sp.”, and Candidatus “Brocadia sp.” (Fig. 2). Although the total number of clones screened for anammox bacterial 16S rRNA and hzo genes was not very large when considering the sample sizes in this study, our further studies with much more 16S rRNA and hzo gene sequences provide a similar community structure of anammox bacteria at this research area, supporting the obtained results in the present study (Li et al. 2011b). The sediment samples of the present study were directly collected from inside or outside of the mangrove forest, which has been strongly affected by anthropogenic input including wastewater and urbanization development (Wang et al. 2006). According to the results from a long-term ecological monitoring project, large quantity of wastewater with different types of pollutants, including heavy metals, excessive nutrients and organic substances, is directly discharged into this area, which seriously threatens the biodiversity in this ecosystem (Mai Po Inner Deep Bay Ramsar Site Monitoring Programme reports from 2003 to 2008, “unpublished data”). Mangrove serves a conjunct region of terrestrial and marine environments at this area, where the anammox bacteria such as “Kuenenia” and “Brocadia” usually found in freshwater and terrestrial ecosystems delivered by the adjacent river would mix with the dominant marine anammox bacteria “Scalindua” mixed by regular tides. As a result, not only “Scalindua” related hzo gene sequences but also some related to the “Kuenenia” and “Brocadia” anammox bacteria are also detected. These Kuenenia-like or Brocadia-like anammox bacteria cannot be detected by 16S rRNA gene possibly due to the discrimination of the highly specific 16S rRNA gene targeting PCR primers, but indicated that there are still many non-described marine anammox bacteria in mangrove sediments.

One of the most interesting findings from the present study is the spatial distribution of anammox bacteria in mangrove sediments. Due to the river discharge and tidal movement carrying available nutrients in water and also anoxic condition in mangrove sediments, it is not surprising to find the existence of anammox bacteria with high diversity in all surface sediment samples. However, in the lower layer sediment samples collected closely to the mangrove trees, anammox bacteria have low diversity and abundance, even could not be detected in some location (S0-l), regardless of 16S rRNA or hzo genes used as biomarkers (Figs. 1, 2). Furthermore, anammox bacteria at S0-s, the site immediately to the mangrove trees, are significantly different from the other sampling sites, forming a unique community structure (Fig. 4). In addition, hzo abundances were decreasing at surface layer while increasing at lower layer along with distances to mangrove trees, and mangrove surface layer sediment samples have higher hzo gene abundances than the lower layer samples, while the sample (S2) located far away from mangrove has the reversed trend (Fig. 3). Previous studies have proposed a close microbe-nutrient-plant relationship that functions as a mechanism to recycle and conserve nutrients, such as nitrogen, in the mangrove ecosystem (Holguin et al. 2001). The diverse microbial community with high activities continuously transforms nutrients from dead mangrove vegetation into sources of nitrogen, phosphorus, and other nutrients that can be used by the mangrove trees again. In turn, plant-roots transport O2 into sediments and their exudates serve as substrates for the microorganisms (Holguin et al. 2001). Since anammox bacteria is strictly anaerobic bacteria, which require nitrite and ammonium as substrates for growth, the existence of mangrove trees would have competitive interaction with anammox bacteria for available nitrogen or some other terms. Meanwhile, different nitrogen-utilizing bacteria, such as the ammonium-oxidizers, nitrite-oxidizers, and denitrifiers in mangrove sediments might also have a complex coupling with anammox bacteria due to the same nitrogen substrates or products in these nitrogen microbial processes (Flores-Mireles et al. 2007). A complex interaction between anammox bacteria and other nitrogen-utilizing ones for consumption or production of ammonium or nitrite in the Black Sea water column and Peruvian oxygen minimum zone are revealed (Lam et al. 2007, 2009). Thus, the special distribution of anammox bacteria in mangrove sediment spatially might also due to the interactions between anammox bacteria and other nitrogen-utilizing microorganisms, such as ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) and ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB). In our previous study, we reported that AOA diversity and abundances were significantly correlated with hzo gene abundance at the same research sites, which provides further evidence on the interactions between AOA and anammox bacteria (Li et al. 2011a).

On the other hand, correlation analysis further shows that 16S rRNA and hzo gene diversities have strong positive correlations with sediment redox potential, and hzo gene abundance has a significant correlation with the molar ratio of ammonium to nitrite, which are reasonable as oxygen and nitrogen in sediments are important factors affecting the diversity and abundances of anammox bacteria.

In conclusion, the phylogenetic diversity, distribution and abundances of anammox bacteria are investigated in mangrove sediment transect with different depths. The phylogeny of functional biomarker HZO protein shows a more complex anammox bacteria community structure than the phylogeny of 16S rRNA gene in these research areas.

References

Alongi DM (2002) Present state and future of the world’s mangrove forests. Environ Conserv 29:331–349

American Public Health Association (1995) Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. APHA, Washington, DC

Byrne N, Strous M, Crepeau V, Kartal B, Birrien JL, Schmid M, Lesongeur F, Schouten S, Jaeschke A, Jetten M, Prieur D, Godfroy A (2009) Presence and activity of anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing bacteria at deep-sea hydrothermal vents. ISME J 3:117–123

Cole JR, Chai B, Farris RJ, Wang Q, Kulam SA, McGarrell DM, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM (2005) The Ribosomal Database Project (RDP-II): sequences and tools for high-throughput rRNA analysis. Nucleic Acids Res 33:D294–D296

Dale OR, Tobias CR, Song B (2009) Biogeographical distribution of diverse anaerobic ammonium oxidizing (anammox) bacteria in Cape Fear River estuary. Environ Microbiol 11:1194–1207

Devol AH (2003) Nitrogen cycle: solution to a marine mystery. Nature 422:575–576

Flores-Mireles AL, Winans SC, Holguin G (2007) Molecular characterization of diazotrophic and denitrifying bacteria associated with mangrove roots. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:7308–7321

Francis CA, Beman JM, Kuypers MM (2007) New processes and players in the nitrogen cycle: the microbial ecology of anaerobic and archaeal ammonia oxidation. ISME J 1:19–27

Holguin G, Vazquez P, Bashan Y (2001) The role of sediment microorganisms in the productivity, conservation, and rehabilitation of mangrove ecosystems: an overview. Biol Fertil Soils 33:265–278

Jetten MS, Sliekers O, Kuypers M, Dalsgaard T, van Niftrik L, Cirpus I, van de Pas-Schoonen K, Lavik G, Thamdrup B, Le Paslier D, Op den Camp HJ, Hulth S, Nielsen LP, Abma W, Third K, Engstrom P, Kuenen JG, Jorgensen BB, Canfield DE, Sinninghe Damste JS, Revsbech NP, Fuerst J, Weissenbach J, Wagner M, Schmidt I, Schmid M, Strous M (2003) Anaerobic ammonium oxidation by marine and freshwater planctomycete-like bacteria. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 63:107–114

Kartal B, Rattray J, van Niftrik LA, van de Vossenberg J, Schmid MC, Webb RI, Schouten S, Fuerst JA, Damste JS, Jetten MS, Strous M (2007) Candidatus “Anammoxoglobus propionicus” a new propionate oxidizing species of anaerobic ammonium oxidizing bacteria. Syst Appl Microbiol 30:39–49

Kartal B, van Niftrik L, Rattray J, van de Vossenberg JL, Schmid MC, Sinninghe Damste J, Jetten MS, Strous M (2008) Candidatus ‘Brocadia fulgida’: an autofluorescent anaerobic ammonium oxidizing bacterium. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 63:46–55

Klotz MG, Stein LY (2008) Nitrifier genomics and evolution of the nitrogen cycle. FEMS Microbiol Lett 278:146–156

Kristensen E, Jensen MH, Banta GT, Hansen K, Holmer M, King GM (1998) Transformation and transport of inorganic nitrogen in sediments of a south-east Asian mangrove forest. Aquat Microb Ecol 15:165–175

Kuenen JG (2008) Anammox bacteria: from discovery to application. Nat Rev Microbiol 6:320–326

Kuypers MM, Sliekers AO, Lavik G, Schmid M, Jorgensen BB, Kuenen JG, Sinninghe Damste JS, Strous M, Jetten MS (2003) Anaerobic ammonium oxidation by anammox bacteria in the Black Sea. Nature 422:608–611

Kuypers MM, Lavik G, Woebken D, Schmid M, Fuchs BM, Amann R, Jorgensen BB, Jetten MS (2005) Massive nitrogen loss from the Benguela upwelling system through anaerobic ammonium oxidation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:6478–6483

Lam P, Jensen MM, Lavik G, McGinnis DF, Muller B, Schubert CJ, Amann R, Thamdrup B, Kuypers MM (2007) Linking crenarchaeal and bacterial nitrification to anammox in the Black Sea. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:7104–7109

Lam P, Lavik G, Jensen MM, van de Vossenberg J, Schmid M, Woebken D, Gutierrez D, Amann R, Jetten MS, Kuypers MM (2009) Revising the nitrogen cycle in the Peruvian oxygen minimum zone. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:4752–4757

Li XR, Du B, Fu HX, Wang RF, Shi JH, Wang Y, Jetten MS, Quan ZX (2009) The bacterial diversity in an anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing (anammox) reactor community. Syst Appl Microbiol 32:278–289

Li M, Hong Y, Klotz MG, Gu J-D (2010) A comparison of primer sets for detecting 16S rRNA and hydrazine oxidoreductase genes of anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing bacteria in marine sediments. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 86:781–790

Li M, Cao HL, Hong Y, Gu J-D (2011a) Seasonal dynamics of anammox bacteria in estuarial sediment of the Mai Po Nature Reserve revealed by analyzing the 16S rRNA and hydrazine oxidoreductase (hzo) genes. Microbes Environ 26:15–22

Li M, Cao HL, Hong Y, Gu J-D (2011b) Spatial distribution and abundances of ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) and ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (AOB) in mangrove sediments. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 89:1243–1254

Lozupone C, Hamady M, Knight R (2006) UniFrac–an online tool for comparing microbial community diversity in a phylogenetic context. BMC Bioinformatics 7:371

Meyer RL, Risgaard-Petersen N, Allen DE (2005) Correlation between anammox activity and microscale distribution of nitrite in a subtropical mangrove sediment. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:6142–6149

Penton CR, Devol AH, Tiedje JM (2006) Molecular evidence for the broad distribution of anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing bacteria in freshwater and marine sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 72:6829–6832

Purvaja R, Ramesh R, Ray AK, Rixen T (2008) Nitrogen cycling: a review of the processes, transformations and fluxes in coastal ecosystems. Curr Sci 94:1419–1438

Quan ZX, Rhee SK, Zuo JE, Yang Y, Bae JW, Park JR, Lee ST, Park YH (2008) Diversity of ammonium-oxidizing bacteria in a granular sludge anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing (anammox) reactor. Environ Microbiol 10:3130–3139

Rich JJ, Dale OR, Song B, Ward BB (2008) Anaerobic ammonium oxidation (anammox) in Chesapeake Bay sediments. Microb Ecol 55:311–320

Risgaard-Petersen N, Meyer RL, Schmid M, Jeeten MSM, Prast A, Rysgaard S, Revsbech P (2004) Anaerobic ammonium oxidation in an estuarine sediment. Aquat Microb Ecol 36:293–304

Rivera-Monroy VH, Twilley RR (1996) The relative role of denitrification and immobilization in the fate of inorganic nitrogen in mangrove sediments (Términos Lagoon, Mexico). Limnol Oceanogr 41:284–296

Rysgaard S, Glud RN (2004) Anaerobic N2 production in Arctic sea ice. Limnol Oceanogr 49:86–94

Rysgaard S, Glud RN, Risgaard-Petersen N, Dalsgaard T (2004) Denitrification and anammox activity in Arctic marine sediments. Limnol Oceanogr 49:1493–1502

Schalk J, de Vries S, Kuenen JG, Jetten MS (2000) Involvement of a novel hydroxylamine oxidoreductase in anaerobic ammonium oxidation. Biochemistry 39:5405–5412

Schloss PD, Handelsman J (2005) Introducing DOTUR, a computer program for defining operational taxonomic units and estimating species richness. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:1501–1506

Schmid M, Twachtmann U, Klein M, Strous M, Juretschko S, Jetten M, Metzger JW, Schleifer KH, Wagner M (2000) Molecular evidence for genus level diversity of bacteria capable of catalyzing anaerobic ammonium oxidation. Syst Appl Microbiol 23:93–106

Schmid MC, Maas B, Dapena A, van de Pas-Schoonen K, van de Vossenberg J, Kartal B, van Niftrik L, Schmidt I, Cirpus I, Kuenen JG, Wagner M, Sinninghe Damste JS, Kuypers M, Revsbech NP, Mendez R, Jetten MS, Strous M (2005) Biomarkers for in situ detection of anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing (anammox) bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:1677–1684

Schmid MC, Hooper AB, Klotz MG, Woebken D, Lam P, Kuypers MM, Pommerening-Roeser A, Op den Camp HJ, Jetten MS (2008) Environmental detection of octahaem cytochrome c hydroxylamine/hydrazine oxidoreductase genes of aerobic and anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing bacteria. Environ Microbiol 10:3140–3149

Schubert CJ, Durisch-Kaiser E, Wehrli B, Thamdrup B, Lam P, Kuypers MM (2006) Anaerobic ammonium oxidation in a tropical freshwater system (Lake Tanganyika). Environ Microbiol 8:1857–1863

Shimamura M, Nishiyama T, Shigetomo H, Toyomoto T, Kawahara Y, Furukawa K, Fujii T (2007) Isolation of a multiheme protein with features of a hydrazine-oxidizing enzyme from an anaerobic ammonium-oxidizing enrichment culture. Appl Environ Microbiol 73:1065–1072

Singleton DR, Furlong MA, Rathbun SL, Whitman WB (2001) Quantitative comparisons of 16S rRNA gene sequence libraries from environmental samples. Appl Environ Microbiol 67:4374–4376

Strous M, Fuerst JA, Kramer EH, Logemann S, Muyzer G, van de Pas-Schoonen KT, Webb R, Kuenen JG, Jetten MS (1999) Missing lithotroph identified as new planctomycete. Nature 400:446–449

Tal Y, Watts JE, Schreier HJ (2005) Anaerobic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and related activity in Baltimore inner harbor sediment. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:1816–1821

Tamura K, Dudley J, Nei M, Kumar S (2007) MEGA4: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis (MEGA) software version 4.0. Mol Biol Evol 24:1596–1599

Thamdrup B, Dalsgaard T (2002) Production of N2 through anaerobic ammonium oxidation coupled to nitrate reduction in marine sediments. Appl Environ Microbiol 68:1312–1318

Thompson JD, Higgins DG, Gibson TJ (1994) CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties, and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res 22:4673–4680

Trimmer M, Nicholls JC, Morley N, Davies CA, Aldridge J (2005) Biphasic behavior of anammox regulated by nitrite and nitrate in an estuarine sediment. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:1923–1930

van de Graaf AA, Mulder A, de Bruijn P, Jetten MS, Robertson LA, Kuenen JG (1995) Anaerobic oxidation of ammonium is a biologically mediated process. Appl Environ Microbiol 61:1246–1251

Wang Y, Leung PC, Qian PY, Gu J-D (2006) Antibiotic resistance and plasmid profile of environmental isolates of Vibrio species from Mai Po Nature Reserve, Hong Kong. Ecotoxicology 15:371–378

Ward BB, Devol AH, Rich JJ, Chang BX, Bulow SE, Naik H, Pratihary A, Jayakumar A (2009) Denitrification as the dominant nitrogen loss process in the Arabian Sea. Nature 461:78–81

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in part by grants from Agriculture, Fisheries, and Conservation Department of the Hong Kong Government (to J-DG), Knowledge Innovation Key Project of The Chinese Academy of Sciences (KZCX2-YW-QN207), National Natural Science Foundation of China (3080032), Guangdong Province Natural Science Foundation (84510301001692), and a start-up fund for Excellent Scholarship of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (07YQ091001) (to Y-G H). We would like to thank Jessie Lai for her laboratory assistance at The University of Hong Kong.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, M., Hong, YG., Cao, HL. et al. Mangrove trees affect the community structure and distribution of anammox bacteria at an anthropogenic-polluted mangrove in the Pearl River Delta reflected by 16S rRNA and hydrazine oxidoreductase (HZO) encoding gene analyses. Ecotoxicology 20, 1780–1790 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10646-011-0711-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10646-011-0711-4