Abstract

There is still only a small number of studies dedicated to Southern Ocean benthic biomass, especially on species level. Here, we analyze polychaete biomass in two areas of the Antarctic fjord Ezcurra Inlet characterized by different levels of disturbance associated with activity of glaciers. Material was collected in March 2007 in the 90–130 m depth range. Twenty van Veen grab (0.1 m2) samples were collected in the inner area of the fjord and 20 in the fjord mouth. Cluster analysis clearly separated those two parts of the fjord. Mean total biomass was significantly higher in the outer region (14.4 ± 5.5 g/0.1 m2) compared with the inner part (3.6 ± 0.8 g/0.1 m2). The highest biomass in the outer, not disturbed area was noted for Amphitrite kerguelensis, Aphelochaeta/Chaetozone, Scalibregma inflatum, Euchone pallida and Maldane sarsi antarctica, while in the inner region, only Aphelochaeta/Chaetozone had high biomass values. Average individual biomass and biomass of majority of polychaete functional groups was also higher in the outer area. Comparison of species composition and abundance with data collected 30 years ago in the studied area revealed also important differences in community structure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Antarctic benthic biomass is characterized by large variation associated with intensity of disturbance processes and depth (Brey and Gerdes 1997). Distribution patterns in zoobenthic biomass may further vary depending on taxonomic and ecological groups (Saiz-Salinas et al. 1997; Pabis et al. 2011). Despite some earlier studies of the Southern Ocean benthic fauna (e.g., White and Robins 1972; Saiz-Salinas and Ramos 1999; Piepenburg et al. 2002; Barnes and Brockington 2003), the knowledge about the distribution of benthic biomass is still very scarce compared with the analysis of abundance. Moreover, almost all the previous researches were based on the analysis of higher taxa, and there are only single studies on biomass at species level (Bromberg et al. 2000; Pabis et al. 2014a). Therefore, identifying key species from various taxonomic groups that constitute the core of biomass at various sites is very important for further discussion on the ecology of the Antarctic benthic communities. Such studies are especially important in the context of the ongoing climate change observed in the region of the West Antarctic Peninsula (WAP) (Clarke et al. 2012). Semi-closed ecosystems of glacial fjords such as Ezcurra Inlet are considered highly vulnerable to those changes (Smale and Barnes 2008; Sicinski et al. 2011; Weslawski et al. 2011; Grange and Smith 2013). The recent synthesis prepared in the framework of the Census of Antarctic Marine Life (CAML) pointed out that Admiralty Bay is a model system for the studies focusing on the climate change influence on benthic fauna (Sicinski et al. 2011). It was also highlighted recently that warming could result in declining of body size and reduced biomass of various organisms, including benthic macrofauna (Linse et al. 2006; Daufresne et al. 2009; Okamura et al. 2011). Thus, the baseline knowledge on the biomass will be needed to allow for future comparisons and further monitoring. Moreover, the comparison between sites located at different distances from the glaciers may mimic future changes and allows to create possible reaction scenarios (Wlodarska-Kowalczuk and Weslawski 2001; Weslawski et al. 2011).

Polychaetes are ideal organisms for such studies. They are among the predominant taxa that build Antarctic benthic communities in terms of species richness and abundance (Gambi et al. 1997; Sicinski 2004; De Broyer et al. 2011; Parapar et al. 2011), as well as the most important biomass component when non-colonial benthic invertebrates are taken into account (Jazdzewski et al. 1986; Mühlenhardt-Siegel 1988; Saiz-Salinas et al. 1998; Saiz-Salinas and Ramos 1999; Pabis et al. 2011). Polychaetes are very good ecological indicators of changes in ecosystem functioning (Olsgard et al. 2003; Giangrande et al. 2005) and their high functional diversity allows for studies of ecological variability (Fauchald and Jumars 1979; Pagliosa 2005).

The aim of this study was to analyze the polychaete biomass at two areas of the glacial fjord Ezcurra Inlet characterized by different levels of glacial disturbance. Biodiversity analysis of those data was used for the bipolar comparison between Ezcurra Inlet and Arctic fjord Hornsund (Pabis et al. 2014b). It is the first study with emphasis on polychaete biomass on the species level in the areas affected by glacial sedimentation inflow.

Materials and methods

Study area

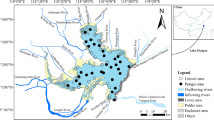

Ezcurra Inlet is a semi-closed fjord located in Admiralty Bay (King George Island); (Sicinski et al. 2011). The maximum depth of this fjord reaches 280 m. The inner and outer areas of this inlet are partially separated by a submerged sill (Marsz 1983) and differ in terms of intensity of glacial disturbance and hydrological properties (Sicinski et al. 2011; Campos et al. 2013).

The inner part of the fjord is under a direct influence of large tidewater glaciers (Braun and Grossmann 2002). This part of the fjord is characterized by very weak currents (Campos et al. 2013). The amount of mineral suspension in the water at this area was estimated at more than 100 mg dm−3 (Pecherzewski 1980), and sedimentation inflow is reflected in the character of bottom deposits, characterized by silt and clay sediments (Sicinski 2004; Campos et al. 2013). Water turbidity is also high in this area (Lipski 1987), and primary production is influenced by glacial sedimentation that cause low concentrations of phytoplankton (Tokarczyk 1986).

The outer area of the fjord is not influenced by glaciers (Braun and Grossman 2002). The amount of mineral suspension in water is much lower than in the inner region and reaches about 15 mg dm−3 (Pecherzewski 1980), and the water turbidity is low (Lipski 1987). The area is under the influence of strong current circulation (Sicinski et al. 2011; Campos et al. 2013). It is characterized by sandy mud, poorly sorted deposits with the presence of dropstones (Sicinski 2004; Campos et al. 2013).

Sampling

Sampling was done in March 2007, in the fjord mouth (100–130 m depth range) and in the inner area of the fjord (90–130 m depth range; Fig. 1). Twenty van Veen grab (0.1 m2) samples were collected at five stations (four replicates at each station) in each of those two areas. Altogether 40 quantitative samples were collected, sieved through 0.5 mm mesh and fixed in 4 % buffered formalin solution. An additional van Veen grab sample was collected at each station for TOC and granulometric analysis of the sediments.

Data analysis

The polychaete material was identified to species level except for the members of the family Cirratulidae that were identified to generic level. Those morphologically very similar taxa are often destroyed and lack important diagnostic features, thus require special sorting and washing techniques difficult to apply in standard van Veen grab sampling for ecological studies. Biomass was of each polychaete species in each sample that was measured with accuracy of 0.001 g as blotted wet weight. In the case of tubiculous species, the tubes were removed. Similarity between the samples was calculated using the Bray–Curtis formula. Hierarchical agglomerative clustering of square-root-transformed data was done. Group average method was applied (Clark and Warwick 2001). This part of analysis was done in Primer 6 package. Mean biomass and density (0.1 m2) with standard deviation (SD) were calculated for the species that had total biomass above 1 g and frequency of occurrence ≥20 % in the studied material. The average individual biomass (AIB) of those species in each sample was also calculated as biomass divided by abundance in order to estimate average organism size (Wlodarska-Kowalczuk et al. 2005).

Each species was also assigned to functional groups following the classification provided by Fauchald and Jumars (1979). This classification has already been used in the analysis of polychaete communities in polar fjords (e.g., Włodarska-Kowalczuk et al. 2005; Kedra et al. 2013). Mean biomass with SD of each functional group in both studied areas was calculated. Differences between the biomass values in both areas were tested using Mann–Whitney U test in the Statistica 6 package.

Results

The inner area was characterized by silty clay sediments. Sediments at the outer area were categorized as sandy silt with the presence of dropstones. Organic matter content (TOC) in the sediments in the outer area was as high as 2.58–4.83 %.

Mean total polychaete biomass was significantly higher in the fjord mouth (14.4 ± 5.5 g/0.1 m2, maximum 27.4, minimum 7.1) than in the inner area (3.6 ± 0.8 g/0.1 m2 maximum 5.2, minimum 2.1) (Mann–Whitney U test p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). Samples from both areas were clearly separated in the cluster analysis forming two groups at high level of similarity (Fig. 3).

From 90 species recorded (83 in outer area and 58 in the inner area), 20 had a total biomass in the whole studied material that exceeded 1 g and frequency of occurrence ≥20 % (Table 1). All those 20 species were recorded in the outer area of the fjord. In the inner region, 17 of those 20 species were found (Table 1). The most important biomass components in the fjord mouth were Amphitrite kerguelensis (4.2 ± 4.3 g/0.1 m2), Aphelochaeta/Chaetozone (1.6 ± 0.6 g/0.1 m2), Scalibregma inflatum (1.3 ± 0.6 g/0.1 m2), Euchone pallida (1.3 ± 1.3 g/0.1 m2) and Maldane sarsi antarctica (1.0 ± 0.6 g/0.1 m2). All those species except for A. kerguelensis had also high densities in this area (Table 1). In the inner region, only Aphelochaeta/Chaetozone had high biomass values (1.8 ± 0.6 g/0.1 m2). Mean biomass of all other polychaetes did not exceed 0.4 g/0.1 m2. Species such as Helicosiphon biscoeensis, Asychis amphiglypta and Lumbriclymenella robusta that were important components of biomass and abundance in the outer region were absent in the inner part of the fjord (Table 1). Some of the most abundant species (Laonice weddellia, Levinsenia gracilis, Capitellidae gen. sp.) had very low biomass reaching mean values of only 0.1 g/0.1 m2 (Table 1). AIB was also higher in the fjord mouth than in the inner area for almost all polychaetes. In case of species such as S. inflatum, E. pallida and M. sarsi antarctica, this value was an order of magnitude higher (Table 1). Differences between outer and inner region in biomass, density and AIB for majority of the polychaete taxa were significant (Table 1).

Functional groups that had the highest biomass in the outer area were sessile and motile tentaculate surface deposit feeders SST (4.8 ± 4.2 g/0.1 m2) and SMT (1.6 ± 0.6 g/0.1 m2), motile and burrowing, sessile, non-jawed polychaetes BSX (2.9 ± 1.4 g/0.1 m2) and BMX (1.3 ± 0.6 g/0.1 m2), and sessile, tentaculate filter-feeders FST (1.8 ± 1.3 g/0.1 m2). In the inner area, only SMT had relatively high biomass (1.7 ± 0.6 g/0.1 m2). There were significant differences between the biomass values of all functional groups except of CMJ, SMT and CDJ (Mann–Whitney U test p < 0.001) (Table 2).

Discussion

It was already demonstrated that polychaetes could constitute even 70 % of biomass in some areas of the Southern Ocean (e.g., Mühlenhardt-Siegel 1988; Saiz-Salinas et al. 1997, 1998; Bromberg et al. 2000; Piepenburg et al. 2002; Pabis et al. 2011). However, almost all previous studies of the Antarctic benthic communities were focused on total polychaete biomass, and there is only scarce knowledge on biomass of particular species (Bromberg et al. 2000; Barbosa et al. 2010), especially when compared to the abundance data (e.g., Richardson and Hedgpeth 1977; Gambi et al. 1997; San Martin et al. 2000; Sicinski 2004; Neal et al. 2011; Parapar et al. 2011). Such data are very important for future assessments of the energy flow in the Antarctic benthic ecosystem. Relation between body mass/size and abundance is one of the main determinants of resources used (Saiz-Salinas and Ramos 1999; Dinmore and Jennings 2004; White et al. 2007). Our study demonstrated that AIB in taxa such as Aphelochaeta/Chaetozone or M. sarsi antarctica is half as large in the glacially disturbed area compared with the fjord mouth. Decrease in total macrozoobenthic biomass was already demonstrated for the benthic fauna in areas affected by various disturbance processes (e.g., Pearson and Rosenberg 1978; Gonzalez-Oreja and Saiz-Salinas 1998; Je et al. 2003). Studies done in the Arctic fjords showed also that influence of glacial sedimentation on benthic fauna is expressed in similar way as in sites affected by pollution events or other types of disturbance (Włodarska-Kowalczuk and Pearson 2004; Włodarska-Kowalczuk et al. 2005). On the other hand, some research proved that biomass could increase at sites affected by moderate levels of disturbance as a result of increasing dominance of smaller animals (Jennings et al. 2001). In our study, the density of small, motile surface deposit feeders such as cirratulids was much higher in the inner part of the fjord; however, this difference was not reflected in the biomass value due to large decrease in average individual body mass. Large differences in AIB between the two studied sites were found for the species representing various functional groups, including large size structural taxa such as maldanids and filtrators (taxa considered vulnerable to disturbance) (Moore 1977; Widdicombe et al. 2004) as well as motile surface deposit feeders such as cirratulids that are considered resistant to various types of disturbance (Borja et al. 2000). It is also worth mentioning that the scale of differences between various species differs. Study of AIB was done in the Arctic fjord; however, this analysis summarized the data for all benthic macroinvertebrates, not even separated into main higher taxa (Wlodarska-Kowalczuk et al. 2005). Nevertheless, those analyses demonstrated that AIB was lower in the inner part of the fjord. Our study has shown that those patterns may differ depending on the species. Those discrepancies suggest that we need a more careful look at the species and functional group level.

In the Admiralty Bay, the data on the biomass of particular polychaete species are available for the nearshore zone of Martel Inlet mostly at shallow (8–25 m) sites affected by growlers and icebergs (Bromberg et al. 2000; Barbosa et al. 2010). This area is shaped by different set of environmental factors and cannot be directly compared with our results. Although it is worth mentioning that mean polychaete biomass in this area did not exceed 6 g/0.1 m2 and was similar to values recorded in the inner area of Ezcurra Inlet. It demonstrated that those two disturbance agents (mineral sedimentation inflow and direct impact of ice) may have similar influence on some of the basic parameters of the benthic community structure. The most important biomass components in shallow areas of the Martel Inlet were different. Large predators Barrukia cristata and Aglaophamus trissophyllys had the highest biomass in this area (Bromberg et al. 2000; Barbosa et al. 2010). Both of those species belong to the most abundant epibenthic polychaetes in the shallow sublittoral of Admiralty Bay (Pabis and Sicinski 2010b). In the deeper areas at 60 m, some common infaunal species such as Aphelochaeta cincinnata and L. gracilis have the highest biomass (Barbosa et al. 2010).

It was often mentioned that large maldanids are the most important biomass components of the Southern Ocean polychaete communities mostly because of their large body size and relatively high densities (Gallardo et al. 1977; Richardson and Hedgpeth 1977; San Martin et al. 2000). However, in the Ezcurra Inlet, small surface deposit feeders (SST) had higher biomass than large burrowing species (BMX) even in the outer area. On the other hand, the species that had the highest biomass value in the fjord mouth, large sessile surface deposit feeder A. kerguelensis, occurred at very low densities in this area (maximum value of 4 ind/0.1 m2). Some earlier studies have shown that large benthic species could have lower abundances compared with intermediate size species even if those large animals feed at low trophic level (Warwick and Clarke 1996; Dinmore and Jennings 2004). Large size burrowing species were more abundant in the outer area of the fjord. It was demonstrated that the presence of the larger bioturbators is increasing the ability of other benthic organisms to process organic matter by increasing the oxygen content in the sediments (Widdicombe et al. 2004). It has an important influence not only on the community structure and diversity but could also result in higher total and individual biomass values. On the other hand, reduced individual biomass of cirratulids in the inner area confirms earlier suggestions that species dominating in the near glacial areas can resist disturbance but are not true opportunists that are employing special life-history traits associated with those disturbed sites (Fetzer et al. 2002; Wlodarska-Kowalczuk et al. 2005).

It was suggested that character of benthic fauna in the glacial bays and inner areas of polar fjords may mimic future climate-warming-related changes in benthic communities at sites located at larger distance from glaciers (e.g., Wlodarska-Kowalczuk and Weslawski 2001, Wlodarska-Kowalczuk and Pearson 2004). Therefore, our results from the inner area of Ezcurra Inlet may demonstrate possible future modifications in community structure at sites that at present are not affected by a high level of glacial disturbance. Taking this into account the general decrease in AIB in the inner area of the fjord supports also recent opinions that climate warming could affect body size of various organisms. However, such relationship was discussed mostly in respect to direct influence of temperature that could affect thermoregulation and metabolic processes (Daufresne et al. 2009; Okamura et al. 2011). In the deeper sublittoral of glacial fjords, climate warming is reflected mostly in the increased intensity of disturbance processes along the fjord axis.

Admiralty Bay is probably the most comprehensively studied site in the Southern Ocean (Sicinski et al. 2011), providing a large background knowledge on diversity of benthic communities with special reference to the polychaete fauna based on the material gathered 20–30 years ago when climate warming was not as strongly pronounced as in the present time (e.g., Sicinski 1986, 2004; Petti et al. 2006; Pabis and Sicinski 2010a, b). A recent polychaete diversity comparison (Pabis et al. 2014b) showed that the level of disturbance in Ezcurra Inlet is much lower than in the Arctic fjord Hornsund. On the other hand, it is much higher than in the more southern WAP fjords (Grange and Smith 2013). It could be assumed that Admiralty Bay is at the moderate stage of climate warming between the Arctic fjords and more southern WAP fjords which are dominated by the large ampharetid polychaete Amythas membranifera and characterized by a small proportion of mobile deposit feeders (Grange and Smith 2013). Our results further confirm moderate character of Admiralty Bay because some of the large burrowing species such as M. sarsi antarctica were still present in the inner area of Ezcurra Inlet, while in the Arctic fjords, large maldanids were absent in the near glacial areas (Wlodarska-Kowalczuk and Pearson 2004; Kedra et al. 2013).

Mean polychaete biomass values recorded in the inner and outer areas of Ezcurra Inlet in the material collected in 1980s were very similar to our results from those two sites and equaled 2.2 ± 4.3 and 15.5 ± 9.5, respectively, although investigated areas do no fully correspond with our sampling sites (Pabis et al. 2011). On the other hand, we also noted some surprising differences in polychaete community structure in Ezcurra Inlet compared with earlier study that was based on the quantitative material collected in 1985 (Sicinski 2004). Species such as Leitoscoloplos kerguelensis and Ophelina syringopyge that dominated the inner part of Ezcurra Inlet then (mean density 10.4 ind/0.1 m2, max 57 ind/0.1 m2 and 5.7 ind/0.1 m2, max 25 ind/0.1 m2, respectively) were nearly absent in our samples. L. weddellia, a species that was abundant in our study (Table 1) had maximal abundance per sample of only 1 ind/0.1 m2 in the whole material analyzed in 1985 (Sicinski 2004). It is also surprising that species such as S. inflatum and E. pallida constituted the core of biomass and abundance in the outer area. Both species are very common in the Antarctic (e.g., Hartman 1966; Blake 1981; San Martin et al. 2000; Gambi et al. 2001; Parapar et al. 2011); however, in the studies done in Ezcurra Inlet and central basin of Admiralty Bay in the 1980s, those polychaetes were very rare (maximum abundance of only 1 and 4 ind/0.1 m2, respectively) (Sicinski 2004). Differences in community structure between those two studies are obvious although we cannot link this fact with the climate changes that occurred during the last 30 years in the WAP region, mostly because of lack of long-term data collected within this period in regular time intervals and with use of standardized sampling protocol. Moreover, our analysis was focused only on small spatial scale in two sampling areas and any meaningful general conclusion about dynamics of benthic communities can be made after more comprehensive research. Nevertheless, this pattern seems to be strong, and it certainly needs further studies during the monitoring of the Admiralty Bay waters. There are no quantitative studies analyzing Antarctic benthic diversity and community structure at the scale of decades, although there were no high differences in composition of polychaete communities in Ezcurra Inlet between 1980 (Sicinski 1986) and 1985 (Sicinski 2004), and results of those two studies in respect to abundance of the above mentioned species were similar. Temporal changes in benthic communities attributed to the strong increase in input of Atlantic water into the fjord and increased temperature of the West Spitsbergen Current were already observed in the Arctic Kongsfjorden. However, differences in abundance of dominant polychaete species were relatively small between 1997 and 2006 (Kedra et al. 2010). On the contrary, Renaud et al. (2007) found no change in diversity and species composition of the Arctic benthic communities between 1980 and 2000 as well as between 2000 and 2001 demonstrating low dynamics of benthic fauna in other polar fjord. Our study strongly confirms the great need for similar analyses in the Southern Ocean based on the comparable datasets, including the data on biomass of particular species.

References

Barbosa LS, Soares-Gomes A, Paiva PC (2010) Distribution of polychaetes in the shallow, sublittoral zone of Admiralty Bay, King George Island, Antarctica in the early and late austral summer. Nat Sci 2:1155–1163

Barnes DKA, Brockington S (2003) Zoobenthic biodiversity, biomass and abundance at Adelaide Island, Antarctica. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 249:145–155

Blake JA (1981) The Scalibregmatidae (Annelida: Polychaeta) from South America and Antarctica collected chiefly during the R/Y Anton Bruun, R/V Hero and USNS Eltanin. P Biol Soc Wash 94:1131–1162

Borja A, Franco J, Perez V (2000) A marine biotic index to establish the ecological quality of soft-bottom bentos within European estuarine and coastal environments. Mar Pollut Bull 40:1100–1114

Braun M, Grossmann H (2002) Glacial changes in the areas of Admiralty Bay and Potter Cove, King George Island, maritime Antarctica. In: Beyer L, Bolter M (eds) Geoecology of the Antarctic ice-free coastal landscapes. Springer, Berlin, pp 75–90

Brey T, Gerdes D (1997) Is Antarctic benthic biomass really higher than elsewhere? Antarct Sci 9:266–267

Bromberg S, Nonato EF, Corbisier TN, Petti MAV (2000) Polychaete distribution in the near-shore zone of Martel inlet, Admiralty Bay (King George Island, Antarctica). Bull Mar Sci 67:175–188

Campos LS, Barboza CAM, Bassoi M, Bernardes M, Bromberg S, Corbisier TN, Fontes RFC, Gheller PF, Hajdu E, Kawall HG, Lange PK, Lanna AM, Lavrado HP, Monteiro GCS, Montone RC, Morales T, Moura RB, Nakayama CR, Oackes T, Paranhos R, Passos FD, Petti MAV, Pellizari VH, Rezende CE, Rodrigues M, Rosa LH, Secchi E, Tenenbaum D, Yoneshigue-Valentin Y (2013) Environmental processes, biodiversity and changes in Admiralty Bay, King George Island, Antarctica. Adapt Evol Mar Environ 2:127–156

Clarke KR, Warwick RM (2001) Change in marine communities: an approach to statistical analysis and interpretation. Natural Environment Research Council, Plymouth

Clarke A, Barnes DKA, Bracegirdle TJ, Ducklow HW, King JC, Meredith MP, Murphy EJ, Peck LS (2012) The impact of regional climate change on the marine ecosystem of the Western Antarctic Peninsula. In: Rogers AD, Johnston NM, Murphy EJ, Clarke A (eds) Antarctic ecosystems: an extreme environment in a changing world. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Hoboken, pp 93–120

Daufresne M, Lenfellner K, Sommer U (2009) Global warming benefits the small in aquatic ecosystems. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106:12788–12793

De Broyer C, Danis B, Allcock L, Angel M, Arango C, Artois T, Barnes D, Bartsch I, Bester M, Blachowiak-Samolyk K, Blazewicz M, Bohn J, Brandt A, Brandao SN, David B, de Salas M, Eleaume M, Emig C, Fautin D, George KH, Gillan D, Gooday A, Hopcroft R, Jangoux M, Janussen D, Koubbi P, Kouwenberg J, Kuklinski P, Ligowski R, Lindsay D, Linse K, Longshaw M, Lopez-Gonzalez P, Martin P, Munilla T, Muhlenhardt-Siegel U, Neuhaus B, Norenburg J, Ozouf-Costaz C, Pakhomov E, Perrin W, Petryashov V, Pena-Cantero AL, Piatkowski U, Pierrot-Bults A, Rocka A, Saiz-Salinas J, Salvini-Plawen L, Scarabino V, Schiaparelli S, Schrodl M, Schwabe E, Scott F, Sicinski J, Siegel V, Smirnov I, Thatje S, Utevsky A, Vanreusel A, Wiencke C, Woehler E, Zdzitowiecki K, Zeidler W (2011) How many species in the Southern Ocean? Towards a dynamic inventory of the Antarctic marine species. Deep-Sea Res Part II 58:5–17

Dinmore TA, Jennings S (2004) Predicting abundance-body mass relationships in benthic infaunal communities. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 276:289–292

Fauchald K, Jumars PA (1979) The diet of worms: a study of polychaete feeding guilds. Oceanogr Mar Biol 17:193–284

Fetzer I, Lonne OJ, Pearson T (2002) The distribution of juvenile benthic invertebrates in an arctic glacial fjord. Polar Biol 25:303–315

Gallardo VA, Castillo JG, Retamal MA, Yanez A, Moyano HJ, Hermosilla JG (1977) Quantitative studies on the soft–bottom macrobenthic animal communities of shallow antarctic bays. In: Llano GA (ed) Adaptations within Antarctic ecosystems. Proc 3rd SCAR Symp Antarct Biol. Smithsonian Institution, Washington, pp 361–387

Gambi MC, Castelli A, Guizzardi M (1997) Polychaete populations of the shallow soft bottoms off Terra Nova Bay (Ross Sea, Antarctica): distribution, diversity and biomass. Polar Biol 17:199–210

Gambi M, Patti F, Micaletto G, Giangrande A (2001) Diversity of reproductive features in some Antarctic polynoid and sabellid polychaetes, with a description of Demonax polarsterni sp. n. (Polychaeta, Sabellidae). Polar Biol 24:883–891

Giangrande A, Licciano M, Musco L (2005) Polychaetes as environmental indicators revised. Mar Pollut Bull 50:1153–1162

Gonzalez-Oreja JA, Saiz-Salinas JI (1998) Exploring the relationships between abiotic variables and benthic community structure in a polluted estuarine system. Water Res 32:3799–3807

Grange LJ, Smith CR (2013) Megafaunal communities in rapidly warming fjords along the West Antarctic Peninsula: hotspots of abundance and beta diversity. PloS one 8:e77917

Hartman O (1966) Polychaeta, myzostomidae and sedentaria of Antarctica. Antarct Res Ser 7:1–143

Jazdzewski K, Jurasz W, Kittel W, Presler E, Presler P, Sicinski J (1986) Abundance and biomass estimates of the benthic fauna in Admiralty Bay, King George Island South Shetland Islands. Polar Biol 6:5–16

Je JG, Belan T, Levings C, Koo BJ (2003) Changes in benthic communities along a presumed pollution gradient in Vancouver Harbour. Mar Environ Res 57:121–135

Jennings S, Dinmore TA, Duplisea DE, Warr KJ, Lancaster JE (2001) Trawling disturbance can modify benthic production processes. J Anim Ecol 70:459–475

Kedra M, Włodarska-Kowalczuk M, Weslawski JM (2010) Decadal change in soft-bottom community structure in high arctic fjord (Kongsfjorden, Svalbard). Polar Biol 33:1–11

Kedra M, Pabis K, Gromisz S, Wesławski M (2013) Distribution patterns of polychaete fauna in an Arctic fjord (Hornsund, Spitsbergen). Polar Biol 36:1463–1472

Linse K, Barnes DKA, Enderlein P (2006) Body size and growth of benthic invertebrates along an Antarctic latitudinal gradient. Deep-Sea Res Part II 53:921–931

Lipski M (1987) Variations of physical conditions, nutrients and chlorophyll a contents in Admiralty Bay (King George Island, South Shetland Islands, 1979). Pol Polar Res 8:307–332

Marsz A (1983) From surveys of the geomorphology of the shores and bottom of the Ezcurra Inlet. Oceanologia 15:209–220

Moore PG (1977) Inorganic particulate suspensions in the sea and their effects on marine animals. Oceanogr Mar Biol Annu Rev 15:225–363

Mühlenhardt-Siegel U (1988) Some results on quantitative investigations of macroobenthos in the Scotia Arc (Antarctica). Polar Biol 8:241–248

Neal L, Mincks-Hardy SL, Smith CR, Glover AG (2011) Polychaete species diversity on the West Antarctic Peninsula deep continental shelf. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 428:119–134

Okamura B, O’Dea A, Knowles T (2011) Bryozoan growth and environmental reconstruction by zooid size variation. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 430:133–146

Olsgard F, Brattegard T, Holthe T (2003) Polychaetes as surrogates for marine biodiversity: lower taxonomic resolution and indicator groups. Biodivers Conserv 12:1033–1049

Pabis K, Sicinski J (2010) Polychaete fauna associated with holdfasts of the large brown alga Himantothallus grandifolius in Admiralty Bay, King George Island, Antarctic. Polar Biol 33:1277–1288

Pabis K, Sicinski J (2010) Distribution and diversity of polychaetes collected by trawling in Admiralty Bay—an Antarctic glacial fiord. Polar Biol 33:141–151

Pabis K, Sicinski J, Krymarys M (2011) Distribution patterns in the biomass of macrozoobenthic communities in Admiralty Bay (King George Island, South Shetlands, Antarctic). Polar Biol 34:489–500

Pabis K, Hara U, Presler P, Sicinski J (2014a) Structure of bryozoan communities in an Antarctic glacial fjord (Admiralty Bay, South Shetlands). Polar Biol 37:737–751

Pabis K, Kędra M, Gromisz S (2014b) Distinct or similar? Soft bottom polychaete diversity in Arctic and Antarctic glacial fjords. Hydrobiologia. doi:10.1007/s10750-014-1991-5

Pagliosa PR (2005) Another diet of worms: the applicability of polychaete feeding guilds as a useful conceptual framework and biological variable. Mar Ecol 26:246–254

Parapar J, Lopez E, Gambi MC, Nunez J, Ramos A (2011) Quantitative analysis of soft-bottom polychaetes of the Bellingshausen Sea and Gerlache Strait (Antarctica). Polar Biol 34:715–730

Pearson TH, Rosenberg R (1978) Macrobenthic succession in relation to organic enrichment and pollution of the marine environment. Oceanogr Mar Biol Annu Rev 16:229–311

Pecherzewski K (1980) Distribution and quantity of suspended matter in Admiralty Bay, King George Island, South Shetland Islands. Pol Polar Res 1:75–82

Petti MAV, Nonato EF, Skowronski RSP, Corbisier TN (2006) Bathymetric distribution of the meiofaunal polychaetes in the nearshore zone of Martel Inlet King George Island, Antarctica. Antarct Sci 18:163–170

Piepenburg D, Schmidt MK, Gerdes D (2002) The benthos off King George Island (South Shetland Islands, Antarctica): further evidence for a lack a latitudinal biomass cline in the Southern Ocean. Polar Biol 25:146–158

Renaud PE, Włodarska-Kowalczuk M, Trannum H, Holte B, Węsławski JM, Cochrane S, Dahle S, Gulliksen B (2007) Multidecadal stability of benthic community structure in a high-Arctic glacial fjord (van Mijenfjord, Spitsbergen). Polar Biol 30:295–305

Richardson MD, Hedgpeth JW (1977) Antarctic soft–bottom mecrobenthic community adaptations to a cold, stable, highly productive, glacially affected environment. In: Llano GA (ed.) Adaptations/within Antarctic Ecosystems. Proceeding of the 3–rd SCAR Symposium on Antarctic Biology, Smithsonian Institution, Washington 181–196

Saiz-Salinas JI, Ramos A (1999) Biomass size-spectra of macrobenthic assemblages along water depth in Antarctica. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 178:221–227

Saiz-Salinas JI, Ramos A, Garcia FJ, Troncoso JS, San Martin G, Sanz C, Palacin C (1997) Quantitative analysis of macrobenthic soft-bottom assemblages in South Shetland waters (Antarctica). Polar Biol 17:393–400

Saiz-Salinas JI, Ramos A, Munilla T, Rauschert M (1998) Changes in the biomass and dominant feeding mode of benthic assemblages with depth off Livingston Island (Antarctica). Polar Biol 19:424–428

San Martin G, Parapar J, Garcia FJ, Redondo MS (2000) Quantitative analysis of soft bottoms infaunal macrobenthic polychaetes from South Shetland Islands (Antarctica). Bull Mar Sci 67:83–102

Sicinski J (1986) Benthic assemblages of Polychaeta in chosen regions of the Admiralty Bay (King George Island, South Shetland Islands). Pol Polar Res 7:63–78

Sicinski J (2004) Polychaetes of Antarctic sublittoral in the proglacial zone (King George Island, South Shetland Islands). Pol Polar Res 25:67–96

Sicinski J, Jazdzewski K, De Broyer C, Presler P, Ligowski R, Nonato EF, Corbisier TN, Petti MAV, Brito TAS, Lavrado HP, Blazewicz-Paszkowycz M, Pabis K, Jazdzewska A, Campos LS (2011) Admiralty Bay Benthos Diversity—a census of a complex polar ecosystem. Deep-Sea Res Part II 58:30–48

Smale DA, Barnes DKA (2008) Likely response of the Antarctic benthos to climate-related changes in physical disturbance during the 21st century, based primarily on evidence from the West Antarctic Peninsula region. Ecography 31:289–305

Tokarczyk R (1986) Annual cycle of chlorophyll α in Admiralty Bay 1981–1982 (King George Island, South Shetland). Pol Arch Hydrobiol 3:177–188

Warwick RM, Clarke KR (1996) Relationship between body-size, species abundance and diversity in marine benthic assemblages: facts and artefacts? J Exp Mar Biol Ecol 202:63–71

Weslawski JM, Kendall MA, Włodarska-Kowalczuk M, Iken K, Kędra M, Legezynska J, Sejr MK (2011) Climate change effects on Arctic fjord and coastal mecrobenthic diversity observations and predictions. Mar Biodiv 41:71–85

White MG, Robins MW (1972) Biomass estimates from Borge Bay, Signy Island, South Orkney Islands. Br Antarct Surv Bull 31:45–50

White EP, Morgan Ernest SK, Kerkhoff AJ, Enquist BJ (2007) Relationships between body size and abundance in ecology. Trend Ecol Evol 22:323–330

Widdicombe A, Austen MC, Kendall MA, Olsgard F, Schaanning MT, Dashfield SL, Needham HR (2004) Importance of bioturbators for biodiversity maintenance: indirect effects of fishing disturbance. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 275:1–10

Wlodarska-Kowalczuk M, Pearson TH (2004) Soft-bottom mecrobenthic faunal associations and factors affecting species distributions in an Arctic glacial fjord (Kongsfjord, Spitsbergen). Polar Biol 25:155–167

Wlodarska-Kowalczuk M, Weslawski JM (2001) Impact of climate warming on Arctic benthic biodiversity: a case study of two Arctic glacial bays. Clim Res 18:127–132

Wlodarska-Kowalczuk M, Pearson TH, Kendall MA (2005) Benthic response to chroni natural physical disturbance by glacial sedimentation in an Arctic fjord. Mar Ecol Prog Ser 303:31–41

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by Polish Committee of Scientific Research project No. PBZ-KBN-108/PO4/2004. Krzysztof Pabis was also partially supported from the University of Lodz internal funds. Authors would like to thank captain and crew of m/v Polar Pioneer. We also want to thank Katarzyna Huzarska for help with sediment analysis. Special thanks are due to Jacek Sicinski, a leader of the 2007 expedition to Admiralty Bay. We also want to thank two anonymous reviewers for valuable comments that significantly improved this article.

Conflict of interest

We certify that there is no conflict of interest with any organization regarding the material discussed in the manuscript.

Ethical standards

All procedures performed in studies involving animals were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution or practice at which the studies were conducted. This article does not contain any studies with human participants performed by any of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Communicated by H.-D. Franke.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Pabis, K., Sobczyk, R. Small-scale spatial variation of soft-bottom polychaete biomass in an Antarctic glacial fjord (Ezcurra Inlet, South Shetlands): comparison of sites at different levels of disturbance. Helgol Mar Res 69, 113–121 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-014-0420-5

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10152-014-0420-5