Abstract

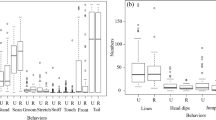

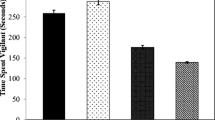

Individuals often produce alarm or mobbing calls when they detect a threat such as a predator. Little is known about whether such calling is affected by the facial orientation of a potential threat, however. We tested for an effect of facial orientation of a potential threat on tufted titmice, Baeolophus bicolor, a songbird that uses chick-a-dee calls in a variety of social contexts. In two studies, a human observer wore an animal mask that either faced or faced away from the focal bird(s). In Study 1, focal birds were individual titmice captured in a walk-in trap, and the observer stood near the trapped bird. In Study 2, focal birds were titmouse flocks utilizing a feeding station and the observer stood near the station. In both studies, calling behavior was affected by mask orientation. In Study 2, foraging and agonistic behavior were also affected. Titmice can therefore perceive the facial orientation of a potential threat, and this perception affects different behavioral systems, including calling. Our results indicate sensitivity of titmice to the facial orientation of a potential predator in two quite different motivational contexts. This work suggests the possibility of strategic signaling by prey species depending upon the perceptual space of a detected predator.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Bartmess-LeVasseur J, Branch CL, Browning SA, Owens JL, Freeberg TM (2010) Predator stimuli and calling behavior of Carolina chickadees (Poecile carolinensis), tufted titmice (Baeolophus bicolor), and white-breasted nuthatches (Sitta carolinensis). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 64:1187–1198

Bateman PW, Fleming PA (2011) Who are you looking at? Hadeda ibises use direction of gaze, head orientation and approach speed in their risk assessment of a potential predator. J Zool 285:316–323

Bednekoff PA, Lima SL (2005) Testing for peripheral vigilance: do birds value what they see when not overtly vigilant? Anim Behav 69:1165–1171

Belguermi A, Bovet D, Pascal A, Prévot-Julliard A-C, Saint Jalme M, Rat-Fischer L, Leboucher G (2011) Pigeons discriminate between human feeders. Anim Cogn 14:909–914

Bern C, Herzog HA Jr (1994) Stimulus control of defensive behaviors of garter snakes (Thamnophis sirtalis): effects of eye spots and movement. J Comp Psychol 108:353–357

Bourke AFG (2011) The validity and value of inclusive fitness theory. Proc R Soc B 278:3313–3320

Branch CL, Freeberg TM (2012) Distress calls in tufted titmice (Baeolophus bicolor): are conspecifics or predators the target? Behav Ecol 23:854–862

Bräuer J, Kaminski J, Call J, Tomasello M (2005) All four great ape species follow gaze around barriers. J Comp Psychol 119:145–154

Brown GE, Macnaughton CJ, Elvidge CK, Ramnarine I, Godin J-GJ (2009) Provenance and threat-sensitive predator avoidance patterns in wild-caught Trinidadian guppies. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 63:699–706

Burger J, Gochfeld M (1981) Discrimination of the threat of direct versus tangential approach to the nest by incubating herring and great black-backed gulls. J Comp Physiol Psychol 95:676–684

Burger J, Gochfeld M (1990) Risk discrimination of direct versus tangential approach by basking black iguanas (Ctenosaura similis): variation as a function of human exposure. J Comp Psychol 104:388–394

Burger J, Gochfeld M (1993) The importance of the human face in risk perception by black iguanas, Ctenosaura similis. J Herpetol 27:426–430

Burger J, Gochfeld M, Murray BG Jr (1991) Role of a predator’s eye size in risk perception by basking black iguana, Ctenosaura similis. Anim Behav 42:471–476

Burger J, Gochfeld M, Murray BG Jr (1992) Risk discrimination of eye contact and directness of approach in black iguanas (Ctenosaura similis). J Comp Psychol 106:97–101

Caro T (2005) Antipredator defenses in birds and mammals. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Carter J, Lyons NJ, Cole HL, Goldsmith AR (2008) Subtle cues of predation risk: starlings respond to a predator’s direction of eye-gaze. Proc R Soc B 275:1709–1715

Clucas B, Marzluff JM, Mackovjak D, Palmquist I (2013) Do American crows pay attention to human gaze and facial expressions? Ethology 119:296–302

Cooper WE Jr (1997) Threat factors affecting antipredatory behavior in the broad-headed skink (Eumeces laticeps): repeated approach, change in predator path, and predator’s field of view. Copeia 1997:613–619

Cooper WE Jr (2003) Risk factors affecting escape behavior by the desert iguana, Dipsosaurus dorsalis: speed and directness of predator approach, degree of cover, direction of turning by a predator, and temperature. Can J Zool 81:979–984

Cooper WE Jr (2011) Influence of some potential predation risk factors and interaction between predation risk and cost of fleeing on escape by the lizard Sceloporus virgatus. Ethology 117:620–629

Cooper WE Jr, Hawlena D, Pérez-Mellado V (2010) Escape and alerting responses by Balearic lizards (Podarcis lilfordi) to movement and turning direction by nearby predators. J Ethol 28:67–73

Cornell HN, Marzluff JM, Percoraro S (2012) Social learning spreads knowledge about dangerous humans among American crows. Proc R Soc B 279:499–508

Courter JR, Ritchison G (2010) Alarm calls of tufted titmice convey information about predator size and threat. Behav Ecol 21:936–942

Curio E (1975) The functional organization of anti-predator behaviour in the pied flycatcher: a study of avian visual perception. Anim Behav 23:1–115

Ekman J (1989) Ecology of non-breeding social systems of Parus. Wilson Bull 101:263–288

Elgar MA (1986) The establishment of foraging flocks in house sparrows: risk of predation and daily temperature. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 19:433–438

Freeberg TM (2008) Complexity in the chick-a-dee call of Carolina chickadees (Poecile carolinensis): associations of context and signaler behavior to call structure. Auk 125:896–907

Furrer RD, Manser MB (2009) Banded mongoose recruitment calls convey information about risk and not stimulus type. Anim Behav 78:195–201

Gaddis P (1979) A comparative analysis of the vocal communication systems of the Carolina chickadee and the tufted titmouse. Dissertation, University of Florida

Gill SA, Bierema AM-K (2013) On the meaning of alarm calls: a review of functional reference in avian alarm calling. Ethology 119:449–461

Griesser M (2008) Referential calls signal predator behavior in a group-living bird species. Current Biol 18:69–73

Grubb TC, Pravosudov VV (1994) Tufted titmouse (Parus bicolor). In: Poole A, Gill F (eds) The birds of North America, No. 86. The Academy of Natural Sciences, Philadelphia PA; The American Ornithologists’ Union, Washington, DC, pp 1–16

Haff TM, Magrath RD (2013) To call or not to call: parents assess the vulnerability of their young before warning them about predators. Biol Lett 9:20130745. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2013.0745

Hailman JP (1989) The organization of the major vocalizations in the Paridae. Wilson Bull 101:305–343

Hamerstrom F (1957) The influence of a hawk’s appetite on mobbing. Condor 59:192–194

Hampton RR (1994) Sensitivity to information specifying the line of gaze of humans in sparrows (Passer domesticus). Behaviour 130:41–51

Harrap S, Quinn D (1995) Chickadees, tits, nuthatches & treecreepers. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Hemsworth PH, Barnett JL, Jones RB (1993) Situational factors that influence the level of fear of humans by laying hens. Appl Anim Behav Sci 36:197–210

Herre EA, Wcislo WT (2011) In defence of inclusive fitness theory. Nature 471:E8–E9

Hetrick SA, Sieving KE (2012) Antipredator calls of tufted titmice and interspecific transfer of encoded threat information. Behav Ecol 23:83–92

Hurlbert SH (1984) Pseudoreplication and the design of ecological field experiments. Ecol Monogr 54:187–211

Jones RB (1980) Reactions of male domestic chicks to two-dimensional eye-like shapes. Anim Behav 28:212–218

Jones KJ, Hill WL (2001) Auditory perception of hawks and owls for passerine alarm calls. Ethology 107:717–726

Kaminski J, Call J, Tomasello M (2004) Body orientation and face orientation: two factors controlling apes’ begging behavior from humans. Anim Cogn 7:216–223

Krams I, Krama T, Igaune K (2006) Alarm calls of wintering great tits Parus major: warning of mate, reciprocal altruism or a message to the predator? J Avian Biol 37:131–136

Krams I, Krama T, Freeberg TM, Kullberg C, Lucas JR (2012) Linking social complexity and vocal complexity: a parid perspective. Philos Trans R Soc B 367:1879–1891

Krause J, Godin J-GJ (1996) Influence of prey foraging posture on flight behavior and predation risk: predators take advantage of unwary prey. Behav Ecol 7:264–271

Kroodsma DE (1989) Suggested experimental designs for song playbacks. Anim Behav 37:600–609

Kroodsma DE, Byers BE, Goodale E, Johnson S, Liu WC (2001) Pseudoreplication in playback experiments, revisited a decade later. Anim Behav 61:1029–1033

Landis JR, Koch GG (1977) The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33:159–174

Langton SRH, Watt RJ, Bruce V (2000) Do the eyes have it? Cues to the direction of social attention. Trends Cogn Sci 4:50–59

Leavesley AJ, Magrath RD (2005) Communicating about danger: urgency alarm calling in a bird. Anim Behav 70:365–373

Lee WY, Lee S, Choe JC, Jablonski PG (2011) Wild birds recognize individual humans: experiments on magpies, Pica pica. Anim Cogn 14:817–825

Lima SL (2002) Putting predators back into behavioral predator-prey interactions. Trends Ecol Evol 17:70–75

Lima SL, Bednekoff PA (1999) Temporal variation in danger drives antipredator behavior: the predation risk allocation hypothesis. Am Nat 153:649–659

Lima SL, Dill LM (1990) Behavioral decisions made under the risk of predation: a review and prospectus. Can J Zool 68:619–640

Marler P (1955) Characteristics of some animal calls. Nature 176:6–8

Marler P (2004) Bird calls: a cornucopia for communication. In: Marler P, Slabbekoorn H (eds) Nature’s music: the science of birdsong. Elsevier, Amsterdam, pp 132–177

Marzluff JM, Walls J, Cornell HN, Withey JC, Craig DP (2010) Lasting recognition of threatening people by wild American crows. Anim Behav 79:699–707

Morton ES (1977) On the occurrence and significance of motivation-structural rules in some bird and mammal sounds. Am Nat 111:855–869

Nolen MT, Lucas JR (2009) Asymmetries in mobbing behaviour and correlated intensity during predator mobbing by nuthatches, chickadees and titmice. Anim Behav 77:1137–1146

Nowak MA (2012) Evolving cooperation. J Theor Biol 299:1–8

Ouattara K, Lemasson A, Zuberbühler K (2009) Campbell’s monkeys concatenate vocalizations into context-specific call sequences. Proc Nat Acad Sci USA 106:22026–22031

Owens JL, Freeberg TM (2007) Variation in chick-a-dee calls of tufted titmice, Baeolophus bicolor: note type and individual distinctiveness. J Acoust Soc Am 122:1216–1226

Pravosudova EV, Grubb TC Jr (2000) An experimental test of the prolonged brood care model in the tufted titmouse (Baeolophus bicolor). Behav Ecol 11:309–314

Pravosudova EV, Grubb TC Jr, Parker PG (2001) The influence of kinship on nutritional condition and aggression levels in winter social groups of tufted titmice. Condor 103:821–828

Roberts G (2008) Evolution of direct and indirect reciprocity. Proc R Soc B 275:173–179

Salva OR, Regolin L, Vallortigara G (2007) Chicks discriminate human gaze with their right hemisphere. Behav Brain Res 177:15–21

Scaife M (1976a) The response to eye-like shapes by birds. I. The effect of context: a predator and a strange bird. Anim Behav 24:195–199

Scaife M (1976b) The response to eye-like shapes by birds. II. The importance of staring, pairedness and shape. Anim Behav 24:200–206

Sieving KE, Hetrick SA, Avery ML (2010) The versatility of graded acoustic measures in classification of predation threats by the tufted titmouse Baeolophus bicolor: exploring a mixed framework for threat communication. Oikos 199:264–276

Soard CM, Ritchison G (2009) ‘Chick-a-dee’ calls of Carolina chickadees convey information about degree of threat posed by avian predators. Anim Behav 78:1447–1453

Stankowich T, Blumstein DT (2005) Fear in animals: a meta-analysis and review of risk assessment. Proc R Soc B 272:2627–2634

Stankowich C, Coss RG (2006) Effects of predator behavior and proximity on risk assessment by Columbian black-tailed deer. Behav Ecol 17:246–254

Taylor C, Nowak MA (2007) Transforming the dilemma. Evolution 61:2281–2292

Templeton CN, Greene E, Davis K (2005) Allometry of alarm calls: black-capped chickadees encode information about predator size. Science 308:1934–1937

Tomasello M, Hare B, Lehmann H, Call J (2007) Reliance on head versus eyes in the gaze following of great apes and human infants: the cooperative eye hypothesis. J Human Evol 52:314–320

Townsend SW, Manser MB (2013) Functionally referential communication in mammals: the past, present, and the future. Ethology 119:1–11

Tvardíková K, Fuchs R (2011) Do birds behave according to dynamic risk assessment theory? A feeder experiment. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 65:727–733

Tvardíková K, Fuchs R (2012) Tits recognize the potential dangers of predators and harmless birds in feeder experiments. J Ethol 30:157–165

Watve M, Thakar J, Kale A, Puntambekar S, Shaikh I, Vaze K, Jog M, Paranjape S (2002) Bee-eaters (Merops orientalis) respond to what a predator can see. Anim Cogn 5:253–259

West SA, Griffin AS, Gardner A (2007) Social semantics: altruism, cooperation, mutualism, strong reciprocity and group selection. J Evol Biol 20:415–432

Wilson DS, Wilson EO (2007) Rethinking the theoretical foundation of sociobiology. Q Rev Biol 82:327–348

Zachau CE, Freeberg TM (2012) Chick-a-dee call variation in the context of “flying” avian predator stimuli: a field study of Carolina chickadees (Poecile carolinensis). Behav Ecol Sociobiol 66:683–690

Acknowledgments

We thank the staffs of Ijams Nature Center (Knoxville, TN), Norris Dam State Park (Norris, TN), and the University of Tennessee Forest Resources, Research, and Education Center (Oak Ridge, TN), for allowing us to record tufted titmice on their grounds. TMF acknowledges the support of a Fulbright Teaching Award to work at Daugavpils University, Latvia, which helped make some of this work possible. Thanks to Paige Crowden, Nicholas Hendershott, Rebecca Weiner, and Christy Whitt for assistance with data collection. Thanks to Julie Bartmess-LeVasseur, David Book, Sheri Browning, Christine Dahlin, David Gammon, Amiyaal Ilany, Arik Kershenbaum, John Marzluff, Jessica Owens, and two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on drafts of this manuscript, and finally to Gordon Burghardt for helpful discussions in 2009 that led to the initiation of this project.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical standard

This work followed the ‘Guidelines for the Treatment of Animals in Behavioural Research and Teaching’ of the Animal Behavior Society and the Association for the Study of Animal Behaviour and was conducted under approved University of Tennessee Animal Care and Use Committee protocol No. 1248. The studies described here complied with the current laws of the USA.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Freeberg, T.M., Krama, T., Vrublevska, J. et al. Tufted titmouse (Baeolophus bicolor) calling and risk-sensitive foraging in the face of threat. Anim Cogn 17, 1341–1352 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-014-0770-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10071-014-0770-z