Abstract

Only a few studies have been carried out in children on the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV). 5-HT3 receptor antagonists have been shown to be more efficacious and less toxic than metoclopramide, phenothiazines and cannabinoids. Most dose studies are available for the 5-HT3 receptor antagonists ondansetron and granisetron. The new 5-HT3 receptor antagonist palonosetron was evaluated in one comparative study so far showing promising activity. Combinations of a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone showed increased efficacy with respect to a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist alone. All paediatric patients receiving chemotherapy of high or moderate emetogenic potential should receive a combination of a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone to prevent acute emesis. No studies have specifically evaluated antiemetic drugs in the prevention of chemotherapy-induced delayed and anticipatory emesis in children. The role of the NK1 receptor antagonists in children has to be further investigated, although one small study is published so far, showing promising activity in the prevention of CINV with aprepitant. The new proposed guideline from the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer and the European Society of Clinical Oncology summarises the updated data from the literature and takes into consideration the existing guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Not every child receiving chemotherapy will experience nausea and vomiting. However, it has been estimated that these symptoms will occur in up to 70% of patients [15, 17, 24]. It is also well recognised that children (above the age of 5 years) are more prone to vomiting than adults [27, 30].

Despite recent significant advances, problems in the control of chemotherapy-induced emesis in children and adolescents remain [2]. Still, only a few studies have been carried out in children on the prevention of chemotherapy-induced emesis, and it is inappropriate to assume that all results obtained in adults can be directly applied to children, since metabolism and side effects of drugs may be different [12, 19, 27]. Furthermore, a cross-comparison of the studies is sometimes difficult because of the significantly different definitions of response rates and nausea rates.

The purpose of this updated Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer (MASCC)/European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) guideline is to provide a consensus statement derived from published articles as well as expert opinion about antiemetic therapy in children. This guideline refers to children and young people (<18 years).

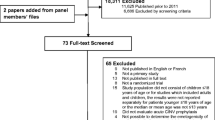

Literature search strategy

Pertinent information from the published literature as of 2004 to June 2009 was retrieved and reviewed for the creation of this guideline. MEDLINE (National Library of Medicine) was searched for pertinent articles. The following keywords or phrases were used: antiemetics, chemotherapy-induced emesis, children, neoplasms, nausea, vomiting, serotonin antagonists, neurokinin-1 receptor antagonists, phenothiazines, butyrophenones, cannabinoids, corticosteroids and metoclopramide. Abstracts were reviewed and articles were excluded, if they possessed any of the following characteristics: review articles and cause for emesis other than chemotherapy.

Between 2004 and June 2009, the following articles could be identified:

-

5-HT3 receptor-antagonists

-

Safety issues: two studies

-

Dose-finding/optimising studies: four studies

-

Comparative studies: two studies

-

-

NK-1 receptor antagonist, aprepitant: one randomised study, two case reports (one in French), one study on liquid formulation of aprepitant

-

Miscellaneous: two studies, impact of an antiemetic pump and value of metopimazine when added to ondansetron

5-HT3 receptor antagonists as monotherapy

Dose-finding studies

The optimal dose and scheduling of the 5-HT3 receptor antagonists have been evaluated in several trials, and since the last consensus conference, three dose-finding studies have been published, whereas one by Hasler and others [4, 7, 13] is retrospective. Unfortunately, almost all of the published studies are small, and it is difficult to identify the absolute optimal oral and intravenous doses of the 5-HT3 receptor antagonists in children [4, 7, 13, 16, 27]. However, most dose studies are available for the 5-HT3 receptor antagonists ondansetron and granisetron. In clinical practice, established doses for ondansetron are 5 mg/m2 or 0.15 mg/kg every 8 h and for granisetron 0.01 mg/kg or 10 μg/kg once a day [5, 18].

The new 5-HT3 receptor antagonist palonosetron was evaluated in one comparative study and so far it showed promising activity [29].

Ondansetron

Since the last update, two studies were published [8, 13]. One study compared the antiemetic efficacy of an intravenous (IV) and orally disintegrating tablet (ODT) of ondansetron in a prospective randomised fashion in 22 children [8]. Complete and major control of emesis was obtained in 92% of patients in the IV group and in 93% of patients in the ODT group. In the other study, the safety of an ondansetron loading dose (16 mg/m2, top 24 mg) was studied in 37 patients. The authors concluded that an IV ondansetron loading seemed to be safe in infants, children and adolescents. However, as this study was retrospective, no firm conclusion can be drawn [13].

Granisetron

Since 2004, one additional study has been published [4]. In this small study including 18 patients (225 cycles), 10 versus 40 μg/kg granisetron were compared in a double-blind crossover, randomised study in acute and delayed nausea/emesis [4]. No significant differences in antiemetic efficacy in terms of nausea and emesis between the dose groups in the first 5 days after the chemotherapy could be detected.

Tropisetron

In the updated literature search, one study including 50 children evaluated the efficacy of tropisetron with a dose of 5 mg in patients weighing less than 20 kg and 10 mg in patients weighing greater than 20 kg [7]. Acute emesis control was achieved overall in 92% of the treated patients. None of the treated patients experienced any adverse events with the used dose of tropisetron.

New comparative studies of 5-HT3 receptor antagonists

Ondansetron versus granisetron

One study compared a single-dose oral granisetron (0.5 mg: 25–50 kg; 1 mg > 50 kg) versus multidose IV ondansetron (0.15 mg/kg tid) for moderately emetogenic cyclophosphamide-based chemotherapy in 33 children (66 cycles) [16]. Complete efficacy defined as no emesis and no use of rescue medication was obtained in 60.6% in the granisetron arm and in 45.5% in the ondansetron arm. Boys were noted to experience a greater rate of vomiting than did girls.

Palonosetron versus granisetron

One small study so far compared ondansetron (8 mg/m2 every 8 h while receiving chemotherapy) versus palonosetron 0.25 mg once (all patients independent of weight) [29]. In this study, 100 cycles were evaluated in patients receiving highly or moderately emetogenic chemotherapy over several days (slightly more cisplatin in the ondansetron group). Complete control of emesis during chemotherapy in the first 24 h, on day 2 and on day 3 was obtained in 92%, 72% and 78% of patients in the palonosetron group and in 72%, 46% and 54% of patients in the ondansetron group. Regarding the delayed phase (days 4–7), complete control of emesis on days 4, 5, 6 and 7 was obtained in 88%, 98% and 100% on days 6 and 7 in the palonosetron group and in 84%, 90%, 94% and 96% in the ondansetron group. In summary, a significant reduction of emesis and nausea was achieved with palonosetron in the first 3 days (defined here as acute phase) in comparison to ondansetron. The antiemetic protection of emesis and nausea in the delayed phase was similar in both arms.

Corticosteroids

Since the last update, no study specifically addressing the dosing, safety or efficacy of corticosteroids has been published. Corticosteroids are more effective antiemetics in chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) than chlorpromazine or metoclopramide [3, 23]. The combination of a steroid and metoclopramide is more effective than chlorpromazine alone [22]. The combination of ondansetron and dexamethasone was superior to ondansetron alone in controlling emetic episodes in children receiving moderately or highly emetogenic chemotherapy [1]. Similar results were obtained by Hirota et al [14]. The optimal dose of steroids in children has to be determined. In clinical practice, a dexamethasone dose ranging from 10 to 14 mg/m2 is usually used [2, 15, 28]. In regard to the safety of corticosteroids, it has to be considered that corticosteroid treatment, especially in children older than 10 years, increases the risk of aseptic osteonecrosis [6, 20, 28]. Furthermore, laboratory studies suggest steroids may interfere with response to chemotherapy in osterosarcoma cell lines, but this has not been shown in vivo [9].

NK1 receptor antagonists

So far, one randomised small study (n = 50, age 11–19 years) is available on the additional use of the NK1 receptor antagonist aprepitant in adolescents [10]. The used dose (125 mg d1, 80 mg days 2–3) of aprepitant was the same as the dose used in adult patients. Blood samples for analysis of aprepitant pharmacokinetic parameters were collected from 17 patients who received aprepitant. The mean plasma aprepitant concentration–time profiles were generally similar between adolescent and historical data from adult subjects. No details about the emetogenicity of the chemotherapy administered were discussed in the paper. In terms of efficacy, the aprepitant regimen (aprepitant, ondansetron, dexamethasone) when compared to the control regimen (ondansetron, dexamethasone) showed a complete response rate defined as no emesis and no use of rescue medication of 60.7% vs. 38.9% (acute phase), 35.7% vs. 5.6% (delayed phase) and 28.6% vs. 5.6% (overall phase). Although the complete response rate was improved with the aprepitant regimen, statistical significance was not reached, which may be attributed to the small patient number. The parallel pharmacokinetic study conducted suggested that the adult dose regimen was appropriate for adolescents.

Comparative studies with agents of low therapeutic index

Overall, metoclopramide, phenothiazines and cannabinoids have only moderate efficacy and significant side effects, most notably marked sedation and extrapyramidal reactions [11, 26]. As in adults, lorazepam did not show convincing antiemetic efficacy [26]. Ondansetron and granisetron have been shown to be superior to chlorpromazine, dimenhydrinate and to metoclopramide combined with dexamethasone and are less toxic [21, 27].

Two studies have been published since the last update [21, 25]. In the first small pilot study, ondansetron versus ondansetron plus metopimazine was studied in ten patients receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy [25]. The combination antiemetic therapy of ondansetron and metopimazine was more effective especially in the delayed phase than the monotherapy without additional toxicity. In the second study, single dose of granisetron (50 μg/kg) was compared to metoclopramide (2 mg/kg) plus dimenhydrinate (5 mg/kg) in 26 patients receiving 80 cycles of moderate emetogenic chemotherapy [21]. As a result of this study, granisetron as monotherapy was superior to the combination of metoclopramide and dimenhydrinate.

Updated recommendations for the prophylaxis of CINV in children

After the last MASCC Consensus Conference in 2004, new data on CINV suggested a need to update the existing guidelines. Therefore, MASCC convened an Expert Panel for a new International Antiemetic Consensus Conference which was held in Perugia, Italy, 20–22 June 2009. Data from the literature were evaluated, and relevant data were included. These provided the basis for the new proposed MASCC/ESMO guidelines discussed by the experts and described below. The following recommendations refer only to the acute phase of CINV, because no appropriate studies are available for the delayed phase, and therefore no formal recommendation is possible.

5-HT3 receptor antagonists

No designated 5-HT3 receptor antagonist can be recommended (MASCC level of confidence: moderate, level of consensus: high/ESMO level of evidence: II, grade of recommendation: B).

No verifiable high-level evidence-based consensus was possible on the dose of the individual 5-HT3 receptor antagonists.

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are effective antiemetics for CINV especially when combined with a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist (MASCC level of confidence: moderate, level of consensus: high/ESMO level of evidence: II, grade of recommendation: B). No recommendation of an optimal dose of dexamethasone or methylprednisolone is possible. Safety issues (e.g., osteonecrosis) when administering corticosteroids in children must be strongly considered.

NK-1 receptor antagonists

Although there is only one study with the NK-1 receptor antagonist aprepitant in combination with ondansetron and dexamethasone in adolescents, the NK-1 so far has shown promising additional activity. However, the guideline panel will wish to see more well-conducted three-agent trials testing the addition of a NK-1 receptor antagonist to draw firm conclusions for a recommendation.

High emetogenic chemotherapy, acute phase

All paediatric patients should receive antiemetic prophylaxis with a combination of a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone (Table 1) (MASCC level of confidence: moderate, level of consensus: high/ESMO level of evidence: III, grade of recommendation: B).

Moderate emetogenic chemotherapy, acute phase

All paediatric patients should receive antiemetic prophylaxis with a combination of a 5-HT3 receptor antagonist and dexamethasone (MASCC level of confidence: moderate, level of consensus: high/ESMO level of evidence: II, grade of recommendation: B).

Low and minimal emetogenic chemotherapy, acute phase

No recommendation is possible due to a lack of studies in children in this setting.

Conclusions

In the last few years, not enough attention has been paid to the problem of chemotherapy-induced emesis in children. With some exceptions, published studies continue to present so many methodological problems (few patients, nonoptimal design, etc.) that it is impossible to draw firm conclusions. It seems likely that children receiving chemotherapy of minimal emetic potential do not need prophylactic antiemetics, but this is not yet shown; children probably tend to underreport nausea. Furthermore, there is an additional need to investigate the potential role of NK-1 receptor antagonists and the 5-HT3 receptor antagonists palonosetron and transdermal granisetron in well-designed studies. Finally, optimal management of delayed and anticipatory CINV in children is not yet clear.

References

Alvarez O, Freeman A, Bedros A, Call SK, Volsch J, Kalbermatter O, Halverson J, Convy L, Cook L, Mick K et al (1995) Randomized double-blind crossover ondansetron-dexamethasone versus ondansetron-placebo study for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in pediatric patients with malignancies. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 17:145–150

Antonarakis ES, Evans JL, Heard GF, Noonan LM, Pizer BL, Hain RD (2004) Prophylaxis of acute chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in children with cancer: what is the evidence? Pediatr Blood Cancer 43:651–658

Basade M, Kulkarni SS, Dhar AK, Sastry PS, Saikia B, Advani SH (1996) Comparison of dexamethasone and metoclopramide as antiemetics in children receiving cancer chemotherapy. Indian Pediatr 33:321–323

Berrak SG, Ozdemir N, Bakirci N, Turkkan E, Canpolat C, Beker B, Yoruk A (2007) A double-blind, crossover, randomized dose-comparison trial of granisetron for the prevention of acute and delayed nausea and emesis in children receiving moderately emetogenic carboplatin-based chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 15:1163–1168

Brock P, Brichard B, Rechnitzer C, Langeveld NE, Lanning M, Soderhall S, Laurent C (1996) An increased loading dose of ondansetron: a north European, double-blind randomised study in children, comparing 5 mg/m2 with 10 mg/m2. Eur J Cancer 32A:1744–1748

Burger B, Beier R, Zimmermann M, Beck JD, Reiter A, Schrappe M (2005) Osteonecrosis: a treatment related toxicity in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL)—experiences from trial ALL-BFM 95. Pediatr Blood Cancer 44:220–225

Cappelli C, Ragni G, De Pasquale MD, Gonfiantini M, Russo D, Clerico A (2005) Tropisetron: optimal dosage for children in prevention of chemotherapy-induced vomiting. Pediatr Blood Cancer 45:48–53

Corapcioglu F, Sarper N (2005) A prospective randomized trial of the antiemetic efficacy and cost-effectiveness of intravenous and orally disintegrating tablet of ondansetron in children with cancer. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 22:103–114

Davies JH, Evans BA, Jenney ME, Gregory JW (2002) In vitro effects of combination chemotherapy on osteoblasts: implications for osteopenia in childhood malignancy. Bone 31:319–326

Gore L, Chawla S, Petrilli A, Hemenway M, Schissel D, Chua V, Carides AD, Taylor A, Devandry S, Valentine J, Evans JK, Oxenius B (2009) Aprepitant in adolescent patients for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of efficacy and tolerability. Pediatr Blood Cancer 52:242–247

Graham-Pole J, Weare J, Engel S, Gardner R, Mehta P, Gross S (1986) Antiemetics in children receiving cancer chemotherapy: a double-blind prospective randomized study comparing metoclopramide with chlorpromazine. J Clin Oncol 4:1110–1113

Gralla RJ, Roila F, Tonato M (2005) The 2004 Perugia Antiemetic Consensus Guideline process: methods, procedures, and participants. Support Care Cancer 13:77–79

Hasler SB, Hirt A, Ridolfi Luethy A, Leibundgut KK, Ammann RA (2008) Safety of ondansetron loading doses in children with cancer. Support Care Cancer 16:469–475

Hirota T, Honjo T, Kuroda R, Saeki K, Katano N, Sakakibara Y, Shimizu H, Fujimoto T (1993) Antiemetic efficacy of granisetron in pediatric cancer treatment—(2). Comparison of granisetron and granisetron plus methylprednisolone as antiemetic prophylaxis. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 20:2369–2373

Holdsworth MT, Raisch DW, Frost J (2006) Acute and delayed nausea and emesis control in pediatric oncology patients. Cancer 106:931–940

Jaing TH, Tsay PK, Hung IJ, Yang CP, Hu WY (2004) Single-dose oral granisetron versus multidose intravenous ondansetron for moderately emetogenic cyclophosphamide-based chemotherapy in pediatric outpatients with acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Pediatr Hematol Oncol 21:227–235

Jordan K, Schmoll HJ, Aapro MS (2007) Comparative activity of antiemetic drugs. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 61:162–175

Jurgens H, McQuade B (1992) Ondansetron as prophylaxis for chemotherapy and radiotherapy-induced emesis in children. Oncology 49:279–285

Kris MG, Hesketh PJ, Somerfield MR, Feyer P, Clark-Snow R, Koeller JM, Morrow GR, Chinnery LW, Chesney MJ, Gralla RJ, Grunberg SM (2006) American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline for antiemetics in oncology: update 2006. J Clin Oncol 24:2932–2947

Lackner H, Benesch M, Moser A, Smolle-Juttner F, Linhart W, Raith J, Urban C (2005) Aseptic osteonecrosis in children and adolescents treated for hemato-oncologic diseases: a 13-year longitudinal observational study. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 27:259–263

Luisi FA, Petrilli AS, Tanaka C, Caran EM (2006) Contribution to the treatment of nausea and emesis induced by chemotherapy in children and adolescents with osteosarcoma. São Paulo Med J 124:61–65

Marshall G, Kerr S, Vowels M, O’Gorman-Hughes D, White L (1989) Antiemetic therapy for chemotherapy-induced vomiting: metoclopramide, benztropine, dexamethasone, and lorazepam regimen compared with chlorpromazine alone. J Pediatr 115:156–160

Mehta P, Gross S, Graham-Pole J, Gardner R (1986) Methylprednisolone for chemotherapy-induced emesis: a double-blind randomized trial in children. J Pediatr 108:774–776

Morrow GR (1989) Chemotherapy-related nausea and vomiting: etiology and management. CA Cancer J Clin 39:89–104

Nathan PC, Tomlinson G, Dupuis LL, Greenberg ML, Ota S, Bartels U, Feldman BM (2006) A pilot study of ondansetron plus metopimazine vs. ondansetron monotherapy in children receiving highly emetogenic chemotherapy: a Bayesian randomized serial N-of-1 trials design. Support Care Cancer 14:268–276

Relling MV, Mulhern RK, Fairclough D, Baker D, Pui CH (1993) Chlorpromazine with and without lorazepam as antiemetic therapy in children receiving uniform chemotherapy. J Pediatr 123:811–816

Roila F, Feyer P, Maranzano E, Olver I, Clark-Snow R, Warr D, Molassiotos A (2005) Antiemetics in children receiving chemotherapy. Support Care Cancer 13:129–131

Schrey D, Boos J (2009) Antiemetische Therapie in der pädiatrischen. Onkol Im Focus Onkol 9:63–68

Sepulveda-Vildosola AC, Betanzos-Cabrera Y, Lastiri GG, Rivera-Marquez H, Villasis-Keever MA, Del Angel VW, Diaz FC, Lopez-Aguilar E (2008) Palonosetron hydrochloride is an effective and safe option to prevent chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in children. Arch Med Res 39:601–606

Small BE, Holdsworth MT, Raisch DW, Winter SS (2000) Survey ranking of emetogenic control in children receiving chemotherapy. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 22:125–132

Conflicts of interest

Karin Jordan receives compensation for: Advisory Board—Merck Sharp and Dhome (MSD), Glaxo Smith Kline (GSK); and Speakers Bureau—MSD, GSK, Helsinn.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Note

MASCC evidence: Level of confidence (high–low) and grade of consensus (high–low) as used by the Multinational Association of Supportive Care are given in brackets.

ESMO evidence: Levels of evidence (I–V) and grades of recommendation (A–D) as used by the American Society of Clinical Oncology are in given in brackets.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jordan, K., Roila, F., Molassiotis, A. et al. Antiemetics in children receiving chemotherapy. MASCC/ESMO guideline update 2009. Support Care Cancer 19 (Suppl 1), 37–42 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-010-0994-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-010-0994-7