Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of serum mesothelin levels in patients with ovarian masses in comparison to serum cancer antigen (CA) 125 levels.

Methods

This diagnostic accuracy study was conducted in a gynecological oncology unit at Ain Shams University Maternity hospital. Based on radiological and clinical findings, a total of 110 patients were consecutively recruited. Preoperative serum mesothelin levels were assessed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technique, while CA125 levels were determined using electrochemiluminescence immunoassay. All patients underwent exploratory laparotomy. Preoperative serum levels of both markers were correlated to histopathological reports obtained from each patient.

Results

A total of 96 patients were finally analyzed. Of the included 96 patients, 58 (60.4 %) had a benign ovarian lesion, while 38 (39.6 %) had a malignant lesion. The median serum CA125 levels were significantly higher in patients with malignant ovarian lesions than in patients with benign ovarian lesions [335.5 mIU/mL (range 60–1,127 mIU/mL) versus 33.65 mIU/mL (range 10.36–174 mIU/mL), P < 0.001]. The median serum mesothelin level was significantly higher in patients with malignant ovarian lesions than in patients with benign ovarian lesions [104.1 nmol/L (range 6.5–215.4 nmol/L) versus 12.65 nmol/L (range 6.5–102 nmol/L), P < 0.001]. The diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for mesothelin and CA125 were 97.4 and 98.3 % and 97.4 and 56.9 %, respectively. The combination of mesothelin with CA125 did not add predictive value to mesothelin compared with mesothelin alone [same sensitivity (97.4 %) and same specificity (98.3 %)]. Serum mesothelin levels rather than serum CA125 levels were a significant predictor of early-stage ovarian malignancy [Area under the curve = 0.732, 95 % confidence interval (0.543–0.921), P = 0.031].

Conclusion

In ovarian cancer, mesothelin seemed to have the same sensitivity, but a higher specificity than CA125. Combination of mesothelin and CA125 had no advantage over mesothelin alone. Mesothelin rather than CA125 was a significant predictor of early-stage ovarian cancer (stage I/II).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Each year in the United States, approximately 22,000 women are diagnosed with epithelial ovarian cancer (EOC), and >15,000 women die of this disease [1]. Recently, there has been an increase in the survival rate among women with ovarian cancer that can be attributed to improved surgical management and advances in chemotherapeutic modalities.

For a screening test to be considered cost-effective and to detect a sufficient risk in the population being screened, it is mandatory to achieve a positive predictive value (PPV) >10 % [2]. Assays measuring tumor markers in serum or other body fluids have the advantage of being noninvasive, simple to perform, and relatively inexpensive. A suitable screening method would require a sensitivity of 75 % and specificity of 99.7 % to reach a minimally acceptable PPV of 10 % for the identification of ovarian malignancy. Measuring tumor markers in serum or biological body fluids has the merit of being simple to assess, noninvasive, and relatively inexpensive [3].

Mesothelin is a novel tumor marker in patients with mesothelioma and ovarian cancer [4]. Normally, mesothelin, a cell surface protein, is found in mesothelial cells lining the pleura, pericardium, and peritoneum. Elevated mesothelin expression has been observed in several malignancies including mesotheliomas and pancreatic adenocarcinomas. Furthermore, mesothelin has been detected in nearly 70 % of ovarian malignancies and 50 % of bronchogenic adenocarcinomas [5].

Cancer antigen (CA125) is currently the most widely used marker in ovarian cancer diagnosis. However, CA125 has very low sensitivity in identifying patients with early-stage disease [6]. Moreover, CA125 assay has been associated with high false positive rates among patients with benign gynecological lesions [7]. Therefore, this study aimed to evaluate the diagnostic accuracy of serum mesothelin levels in patients with ovarian masses in comparison to serum CA125 levels.

Patients and methods

The current diagnostic accuracy study was conducted in the gynecological oncology unit, at Ain Shams University Maternity Hospital from January 2010 until February 2012. The study protocol was approved by the Ethical Research Committee of the Obstetrics and Gynecology Department at Ain Shams University. A written informed consent was signed by every patient before participating in the study after a thorough explanation of the purpose and procedures of the study.

A total of 110 participants aged 16–75 years were consecutively recruited among the patients presenting to the Gynecological Oncology Outpatient Clinic with a diagnosis of ovarian mass and who were scheduled for surgical management. Provisional diagnoses were based on radiological and clinical findings, while the patients’ final diagnoses were obtained through histopathological evaluations. Patients were then consecutively selected from those with masses suspected to be ovarian tumors. Only patients who were candidates for exploratory laparotomy and for histopathological diagnosis were included.

All patients were subjected to a complete medical history evaluation, thorough clinical examination, and laboratory tests. Routine abdominopelvic ultrasound was performed to assess mass echogenicity, consistency, locularity, laterality, presence of solid areas, as well as presence of ascites. Abdominopelvic computed tomography (CT) scan or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was performed to confirm the diagnosis when relevant, and to identify the presence of any distant secondary malignancies. None of the patients received preoperative chemotherapy. According to histopathological findings, patients were categorized into two groups: Group 1 included patients diagnosed with benign ovarian masses and Group 2 included patients diagnosed with malignant ovarian masses. All malignant cases were properly staged according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics criteria. World Health Organization criteria were used for histological grading of malignant cases [8].

Blood samples

Patient blood samples were collected before surgical intervention. Within 4 h of collection, sera were obtained and frozen at −80 °C until the mesothelin and CA125 assays were performed. Serum mesothelin levels were assessed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) technique, (Fujirebio Diagnostics, Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Mesothelin assay was based on the sandwich principle as described before, with a measuring range of 0.3–32 nmol/L. The within run precision was 1.1–5.3 % and total precision was 4.0–5.3 % [9]. CA125 levels were assessed on Cobas e 411 analyzer (Roch, Tokyo, Japan) using electrochemiluminescence immunoassay based on the sandwich principle, using two monoclonal antibodies as described before and a measuring range of 0.6–5,000 U/mL. The within run precision was 1.4–3.3 % and total precision was 2.5–4.2 % [9].

Sample size justification

Assuming a mean mesothelin level of 0.87 nmol/L in patients with benign ovarian tumors compared to a level of 3.4 nmol/L in patients with malignant ovarian tumors, a sample size of 48 patients in each group was considered sufficient to detect a difference of 0.05 error and 0.80 power of the test [9].

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed using the statistical package for social sciences (SPSS®, IBM, Armonk, NY) for Windows® version 15.0. Normally distributed numerical data were presented as mean and standard deviation (SD) and between-group differences were compared using the unpaired Student’s t test. Non-normally distributed numerical data were presented as median and interquartile range (IQR) and differences between the two groups were compared non-parametrically using the Mann–Whitney U test. Categorical data were presented as number and percentage and inter-group differences were compared using the Pearson Chi-square test (for nominal data) or the Chi square test for trends (for ordinal data). Mean difference with 95 % confidence interval (95 % CI) was calculated to measure the association between mesothelin and the risk of early-stage ovarian malignancy (stage I/II). Associations between measured variables and ovarian malignancy were estimated using receiver operator characteristic (ROC) curves. Validity of study parameters was evaluated in terms of sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and negative predictive value (NPV). Significance level was set at 0.05.

Results

In total, data of 96 patients were analyzed (Fig. 1). The mean age of the studied population was significantly high in patients with malignant ovarian lesions compared to patients with benign ovarian lesions, also, the malignant ovarian lesions were significantly higher among postmenopausal women compared to premenopausal women (Table 1). There were no significant differences between patients with benign ovarian masses and those with malignant ovarian masses regarding, parity, duration of marriage, weight and body mass index (BMI) (Table 1).

During patients’ recruitment, the most common presenting complaint was abdominal pain/discomfort followed by abnormal genital bleeding, gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms, abdominal distension, and abdominal enlargement in 62 (46.6 %), 11 (11.5 %), 10 (10.4 %), 4(4.2 %), and 2 (2.1 %) patients, respectively. Seven (7.3 %) patients were asymptomatic and the mass was incidentally discovered during a pelviabdominal ultrasound scan. There were no significant differences in the presenting complaint between patients with benign ovarian lesions and those with malignant lesions, except for the GI symptoms, which were exclusively present in patients with malignant ovarian lesions [10 (26.3 %) versus 0 (0 %), P < 0.001].

The mass with the largest dimension among the patients was 10.83 ± 5.65 cm. The mass was bilateral in 24 (25 %) patients and unilateral in 72 (75 %); of the latter, the mass was right-sided in 43 (44.8 %) patients and left-sided in 29 (30.2 %) patients. The mass was heterogeneous in 33 (34.4 %) patients and cystic in 63 (65.6 %) patients; of the latter, the cyst was unilocular in 49 (51 %) patients and multilocular in 14 (14.6 %) patients. Ascites was present in 14(14.6 %) patients.

Histopathological results of the ovarian tumors of the study patients are shown in Table 2. Table 3 presents staging and grading of tumors in patients with malignant ovarian tumors.

Median serum CA125 levels were significantly higher in patients with malignant ovarian lesions than in patients with benign ovarian lesions [335.5 mIU/mL (range 60–1,127 mIU/mL) versus 33.65 mIU/mL (range 10.36–174 mIU/mL), P < 0.001]. Median serum mesothelin levels were significantly higher in patients with malignant ovarian lesions than in patients with benign ovarian lesions [104.1 nmol/L (range 6.5–215.4 nmol/L) versus 12.65 nmol/L (range 6.5–102 nmol/L), P < 0.001].

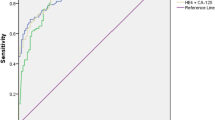

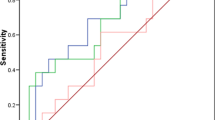

Table 4 presents the accuracy of measured serum tumor markers as predictors of ovarian malignancy in the study patients. According to the best cutoff values retrieved from the ROC curves, serum levels of both CA125 and mesothelin had the same sensitivity (97.4 %), while serum mesothelin was the most specific marker. A serum mesothelin concentration ≥50.6 nmol/L was associated with ovarian malignancy at a sensitivity, specificity, PPV, NPV, positive likelihood ratio(LR+), and negative likelihood ratio(LR−) of 97.4, 98.3, 97.4, 98.3 %, 56.5 and 0.03, respectively (Table 4; Fig. 2).

The combination of mesothelin with CA125 did not improve the predictive value compared with mesothelin alone [same sensitivity (97.4 %) and same specificity (98.3 %)]. Serum mesothelin rather than serum CA125 was a significant predictor of early stages of ovarian malignancy (stage I/II) [area under the curve = 0.732, 95 % CI (0.543–0.921); P = 0.031].

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, none of the previous studies have demonstrated that mesothelin as a single marker had sensitivity as high as CA125 with much more specificity in detecting ovarian cancer. Moreover, serum mesothelin levels rather than serum CA125 levels were a significant predictor of early-stage (stages I/II) ovarian malignancy.

McIntosh et al. [10] mentioned that serum mesothelin levels were elevated in 60–77 % of patients with ovarian cancer, and investigated the use of CA125 and mesothelin as a combination marker in patients with ovarian cancer; they concluded that mesothelin had equal specificity and higher sensitivity than CA125. Moreover, they validated that mesothelin has temporal stability at least as eminent as CA125 and that the combination of both markers was superior to CA125 alone in the diagnosis of ovarian cancer. Furthermore, they concluded that mesothelin was elevated in a fraction of cases that presented with normal serum CA125 levels. Thus, the most useful application of this novel marker may be in combination with CA125 to diagnose ovarian cancer. However, in the present study, we concluded that the combination of mesothelin with CA125 was not beneficial compared to mesothelin alone. Hala et al. [9] mentioned that the mean serum CA125 and mesothelin levels were significantly elevated in malignant cases compared to those in benign cases (P < 0.001), as well as in both benign and malignant cases compared to healthy subjects. Serum mesothelin at a 1.4-nmol/L cutoff value had a lower sensitivity than CA125 in detecting ovarian malignancy (70.7 %) but was more specific than serum CA125. Moreover, they mentioned that the area under the ROC curve for the differentiation of benign from malignant cases was higher for CA125 than mesothelin (0.90 versus 0.89, respectively).

McIntosh et al. concluded that mesothelin may also enhance performance of CA125 in early-stage disease. However, most of the patients (80 %) included in their study were diagnosed in stages III or IV. Conversely, in the present study, 47.4 % of our population was diagnosed in stages I or II, while the remaining 52.6 % were diagnosed in stages III or IV (Table 2). These differences may validate our hypothesis that mesothelin could have better performance in screening and early diagnosis of ovarian cancer than CA125 [10]. The combination of mesothelin and CA125 did not add predictive value to mesothelin compared with mesothelin alone [same sensitivity (97.4 %) and same specificity (98.3 %)]. This indicates that there are no additional benefits from the combination of both markers. However, Moore et al. [11] mentioned that combining CA125 and mesothelin improved the sensitivity compared with that of CA125 alone in detecting ovarian cancer. The purpose of the above-stated clinical dilemma was to select a marker with high sensitivity that can help avoid unnecessary invasive interventions like midline laparotomy and/or radical surgery for the diagnosis of ovarian cancer. Moreover, a marker with high specificity could allow early referral of suspicious cases to highly specialized tertiary centers.

Qiao and Li studied the value of mesothelin in the diagnosis and follow-up of surgically treated ovarian cancer. They investigated 42 patients with ovarian cancer undergoing surgery, 48 with benign ovarian tumors, and 49 healthy controls. Blood samples from patients were collected before surgical intervention and 1 month postoperatively to test serum mesothelin levels. They found that mesothelin levels were higher in patients with ovarian cancer than in the controls. They also determined that the PPV, NPV, sensitivity, and specificity of serum mesothelin were 80.5, 81.6, 78.6, and 83.3 %, respectively, for the diagnosis of ovarian cancer. They concluded that serum mesothelin levels are elevated in ovarian cancer, with high specificity, and can be used as a preoperative diagnostic marker for ovarian cancer. Nevertheless, they did not compare it to CA125 [12]. Havrilesky et al. [13] mentioned that mesothelin is significantly correlated with tumor stage and grade in ovarian cancer, so this biomarker may be useful to monitor disease status in patients with recurrent ovarian cancer.

In the present study, the reason for the high percentage of malignant lesions (nearly 40 %) we observed was probably that patients were recruited from the gynecologic oncology outpatient clinic at Ain Shams University Maternity Hospital, which is a large referral center in Egypt. The strengths of the current study included the inclusion of a high percentage (47.4 %) of patients with early-stage ovarian cancer (stage I/II) which helped us to validate or negate the superiority of mesothelin over CA125 as a significant predictor of early-stage (stages I/II) ovarian malignancy. However, further studies with a large number of patients are still needed.

Our study was limited by the absence of a control group, which may be explained by two facts: first, the absence of screening programs for early detection of ovarian cancer and second, the patient recruitment location, which was a gynecologic oncology outpatient clinic. This made it difficult to encounter healthy controls. Another limitation was that we only assessed serum mesothelin levels. Yet, as Badgwell et al. [14] reported, that urinary mesothelin levelsare more sensitive marker than serum mesothelin levels in differentiating patients with early and late stage ovarian malignancy from healthy controls. Moreover, other investigators demonstrated that, assaying fresh urine for mesothelin may increase the probability of diagnosis of early-stage ovarian disease and would lead to more frequent testing (perhaps at home) [3].

Conclusion

In ovarian cancer, mesothelin seemed to have the same sensitivity, but a higher specificity than CA125. Combination of mesothelin and CA125 had no advantage over mesothelin alone. Mesothelin rather than CA125 was a significant predictor of early-stage ovarian cancer (stage I/II).

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- EOC:

-

Epithelial ovarian cancer

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme linked immunosorbent assay

- GI:

-

Gastrointestinal

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- LR+:

-

Positive likelihood ratio

- LR−:

-

Negative likelihood ratio

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- PPV:

-

Positive predictive value

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- ROC:

-

Receiver operator characteristic

References

American Cancer society (2009) Cancer Facts and Figures. American Cancer Society, Atlanta, pp 1–68

Moore RG, MacLaughlan S, Bast RCJR (2010) Current state of biomarker development for clinical application in epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 116(2):240–245

Hellstrom I, Helstrom KE (2011) fTwo novel biomarkers, mesothelin and HE4, for diagnosis of ovarian carcinoma. Expert Opin Med Diagn 5(3):227–240

Grigoriu BD, Gregoire M, Chahine B, Scherpereel A (2008) New diagnostic markers for malignant pleural mesothelioma. Bull Cancer 95(2):177–184

Hassan R, Schweizer C, Lu KF, Schuler B, Remaley AT, Weil SC et al (2010) Inhibition of mesothelin CA125 interaction in patients with mesothelioma by the antimesothelin monoclonal antibody MORAb-009: implications for cancer therapy. Lung Cancer 68(3):455–459

Terry K, Sluss P, Skates S, Mok S, Ye B, Vitonis A et al (2004) Blood and urine markers for ovarian cancer; a comprehensive review. Dis Markers 20:53–70

Huhtinen K, Suvitie P, Hiissa J, Junnila J, Huvila J, Kujari H et al (2009) Serum HE4 concentration differentiates malignant ovarian tumours from ovarian endometriotic cysts. Br J Cancer 100(8):1315–1319

El Sherbini MA, Sallam MM, Shaban EA, El-Shalakany AH (2011) Diagnostic value of serum kallikrein-related peptidases 6 and 10 versus CA125 in ovarian cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 21(4):625–632

Abdel-Azeez HA, Labib HA, Sharaf SM, Refai AN (2010) HE4 and mesothelin: novel biomarkers of ovarian carcinoma in patients with pelvic masses. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev 11(1):111–116

McIntosh MW, Drescher C, Karlan B, Scholler N, Urban N, Hellstrom KE et al (2004) Combining CA125 and SMR serum markers for diagnosis and early detection of ovarian carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 95:9–15

Moore RG, Brown AK, Miller MC (2008) The use of multiple novel tumour biomarkers for the detection of ovarian carcinoma in patients with a pelvic mass. Gynecol Oncol 108:402–408

Qiao N, Li H (2013) The value of mesothelin in the diagnosis and follow-up of surgically treated ovarian cancer. Eur J Gynaecol Oncol 34(2):163–165

Havrilesky LJ, Whitehead CM, Rubatt JM, Cheek RL, Groelke J, He Q et al (2008) Evaluation of biomarker panels for early stage ovarian cancer detection and monitoring for disease recurrence. Gynecol Oncol 110(3):374–382

Badgwell D, Lu Z, Cole L, Fritsche H, Atkinson EN, Somers E et al (2007) Urinary mesothelin provides greater sensitivity for early stage ovarian cancer than serum mesothelin, urinary hCG free beta subunit and urinary hCG beta core fragment. Gynecol Oncol 106(3):490–497

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Dr. Mohamed I. Ellaithy for his valuable scientific advice and his kind assistance in manuscript revision. Also, I would like to thank Dr. Rania El Kabarity, assistant professor of clinical pathology Ain Shams University, for her contribution in doing the laboratory part of the current study.

Conflict of interest

The authors reported no conflict of interest. All of the authors had substantial contributions to conception and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting and revising the article critically with final approval of the version to be published. The research was funded by the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ibrahim, M., Bahaa, A., Ibrahim, A. et al. Evaluation of serum mesothelin in malignant and benign ovarian masses. Arch Gynecol Obstet 290, 107–113 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-014-3147-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00404-014-3147-2