Abstract

Here, we study distribution of workload and its relationship to colony size among worker ants of Temnothorax albipennis, in the context of colony emigrations. We find that one major aspect of workload, number of items transported by each worker, was more evenly distributed in larger colonies. By contrast, in small colonies, a small number of individuals perform most of the work in this task (in one colony, a single ant transported 57% of all items moved in the emigration). Transporters in small colonies carried more items to the new nest per individual and achieved a higher overall efficiency in transport (more items moved per transporter and unit time). Our results suggest that small colonies may be extremely dependent on a few key individuals. In studying colony organisation and division of labour, the amount of work performed by each individual, not just task repertoire (which tasks are performed at all), should be taken into account.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

References to the industriousness of ants and bees are abundant in popular literature. Indeed, because of their sometimes very conspicuous labour, ants are cited as beacons of rectitude: “Go to the ant, thou sluggard” (Bible, Proverbs 6:6). Similarly, the scientific literature recognises the ecological dominance, fine architecture and supreme organisation of social insects (Hölldobler and Wilson 1990). However, researchers working with individually marked ant or bee colonies often note that a high proportion of ‘workers’, at least in the short-term, does not perform any recognisable work (Lindauer 1952; Herbers 1983; Cole 1986; Schmid-Hempel 1990). Indeed, workload can be very unevenly distributed among workers in a task group (Cole 1986; Hölldobler and Wilson 1990; Robson and Traniello 1999). In particular, some individuals seem to contribute a disproportionate amount of work compared to their nestmates. Such individuals have sometimes been termed ‘elites’ (Hölldobler and Wilson 1990); individuals who play a particularly large role in colony organisation are called ‘key individuals’ (Robson and Traniello 1999). Robson and Traniello distinguish three types of such highly active individuals: ‘catalysts’, ‘organisers’ and ‘performers’. Catalysts are defined as individuals initiating group activity, but not necessarily taking part in it; organisers are defined as sustaining group activity, such that the collective task is not performed if organisers are removed; and performers are individuals that are simply highly active in a task compared to others, contributing most of the work (Robson and Traniello 1999; Robson and Traniello 2002). Highly active individuals and inactive individuals are two aspects of the general phenomenon of a highly skewed workload distribution across workers. Neither phenomenon has been satisfactorily explained (Schmid-Hempel 1990; Robson and Traniello 1999). It has been suggested that the explanation for both individual differences in general and in activity in particular may relate to colony size (Oster and Wilson 1978; Schmid-Hempel 1990; Anderson and McShea 2001).

Social insect colony sizes vary by several orders of magnitude, i.e. in the number of workers they contain (Hölldobler and Wilson 1990). Colony size is often thought to be a major factor in achieving complex collective behaviour (Oster and Wilson 1978; Pacala et al. 1996; Karsai and Wenzel 1998; Bourke 1999; Anderson and McShea 2001; Buhl et al. 2004; O'Donnell and Bulova 2007). For example, larger colony size is thought to be associated with greater individual specialisation (Karsai and Wenzel 1998; Gautrais et al. 2002; Thomas and Elgar 2003), higher rates of information flow and more frequent interactions (Burkhardt 1998; Karsai and Wenzel 1998; Gordon and Mehdiabadi 1999) and higher efficiency at collective behaviours such as task partitioning (Anderson 1999) or exploration (Dornhaus and Franks 2006). These effects may influence individual activity levels, with workers in smaller colonies having to be more flexible (Burkhardt 1998; Karsai and Wenzel 1998) or risk averse (Herbers 1981) than those in larger colonies. However, in several areas, the effects of colony size on collective behaviour seem to differ between study species or depending on the context considered. For example, previous work on communication has suggested that larger colonies may be more successful at foraging with recruitment (Beckers et al. 1989; Beekman et al. 2001; Mailleux et al. 2003), less successful (Jun and Pepper 2003) or collect an equal amount of resource per forager with or without recruitment (Dornhaus et al. 2006). Similarly, results on productivity and its relationship with colony size are also mixed (increasing—Jeanne and Nordheim 1996; Tibbetts and Reeve 2003; Sorvari and Hakkarainen 2007; decreasing—Michener 1964; Karsai and Wenzel 1998; no clear relationship—Strohm and Bordon-Hauser 2003; Bouwma et al. 2006). It is thus likely that colony size may have different effects in different species—and, indeed, this is to be expected, given that selection has shaped social insects to vary in colony size. Similarly, the phenomenon of highly active and inactive individuals may not be easily explained by referring to colony size. Workers in smaller colonies have sometimes been predicted to work harder (Houston et al. 1988; Franks and Partridge 1993), whereas another study predicts higher workload in larger colonies (Schmid-Hempel 1990). Empirical support seems equivocal, with some support for higher individual effort in smaller (Fewell et al. 1991; London and Jeanne 2003) or larger colonies (Schmid-Hempel 1990; Herbers and Choiniere 1996; Plowes and Adams 2005), and some studies finding no clear effect (Wolf and Schmid-Hempel 1990; Beekman 2004). What is the effect of colony size on individual workload, and are larger colonies likely to have a more skewed workload distribution, creating some highly active and many inactive workers?

Here, we investigate whether the distribution of work across monomorphic workers varies between large and small colonies of the ant Temnothorax albipennis. We use the well-studied nest emigration process to measure individual workload. Colonies of T. albipennis occupy natural cavities, for example cracks in rocks, which can often be ephemeral (Möglich and Hölldobler 1974). When a nest site becomes unsuitable, the colony has to find and select a new site, and all adults and brood items have to be moved to it. This process can even be initiated after merely discovering a superior location, i.e. even when the quality of the current nest has not changed and there is no pressing need to emigrate (Dornhaus et al. 2004). First, scout ants leave the nest to search for suitable new nest sites. In this search, prior knowledge of possible sites is taken into account (Franks et al. 2007b). Once a scout has discovered a potential nest site, it assesses the site’s quality and then starts to recruit to it with tandem runs, leading one recruit at a time (Möglich and Hölldobler 1974). The recruit then assesses the nest and may also start recruiting in turn. Multiple criteria are assessed (Franks et al. 2003b), including characteristics of the site itself, such as its structural integrity (Franks et al. 2006b) and cleanness (Franks et al. 2005), as well as outside factors, such as the distance to neighbouring colonies (Franks et al. 2007a). Individuals delay the start of this recruitment by a time interval that is dependent on the quality of the site (Mallon et al. 2001). Tandem runs are a source of positive feedback, with ants accumulating faster in good nest sites. When the population in a new site surpasses a certain number, the quorum threshold, all recruiters switch from tandem running to social carrying, i.e. they start to transport passive individuals and brood to the chosen site (Pratt et al. 2002; Franks et al. 2003a).

We use this collective emigration behaviour specifically to investigate the following questions: How is workload distributed among individuals? How is the skew in workload dependent on colony size? And can we detect effects of workload distribution on colony performance? The answers to these questions are essential for understanding colony organisation and the emergence of division of labour in social insects.

Materials and methods

Colonies of T. albipennis were collected in October 2004 in Dorset, southern England. For this study, we used seven of the largest colonies and seven of the smallest ones collected. For information on the overall distribution of colony sizes in this population, see Franks et al. (2006a). All workers in the colonies were individually marked with paints spots (one on the head, one on the thorax and two on the abdomen). Each colony contained at least one queen (one colony had two queens, another had four) and brood of different stages. After marking, large colonies contained a median of 165 workers (quartiles 152–194 workers) and 318 brood items (quartiles 262–358). Small colonies contained a median of 57 workers (quartiles 43–71) and 180 brood items (quartiles 105–205). The number of workers was counted from a photograph of the colony; the number of brood items was determined as the number of brood transports in the emigration, as small brood items are hard to distinguish on a photograph. This means that our estimate of brood number equals exactly the number of trips needed to transport the brood; however, eggs and small larvae were sometimes carried in clumps, and the real number of eggs and larvae is thus somewhat higher. From these estimates, larger colonies had a higher worker/brood ratio (0.67 workers per brood item compared to 0.34 in small colonies). A larger study of this population had also found a decrease in number of brood per worker with increasing colony size (Dornhaus and Franks 2006). Since some workers lost their markings and a few workers emerged between marking the colony and the emigrations, a median of 87% of the workers were individually marked during the emigrations. A total of 1,223 individually marked ants from large colonies and 412 marked ants from small colonies were monitored for their activity during colony emigrations.

The colonies were housed in nests made of a piece of cardboard from which a cavity had been cut, sandwiched between two glass slides. This method of housing Temnothorax colonies is well established (Franks et al. 2003a, 2005, 2006a, b, 2007a, b; Dornhaus et al. 2004; Dornhaus and Franks 2006). Internal dimensions of the cavity were 33 × 25 × 1 mm (width × depth × height), with a 3-mm entrance. Marked ants could thus be observed through the transparent roof of the nest. For improved colour discrimination, a light brown paper was placed underneath the nest, to provide a light brown background to videos of the colony interior. Nests were placed in large square Petri dishes (220 × 220 mm). Ants were fed with honey solution and dead Drosophila flies weekly.

To induce an emigration of the colony, the top glass slide of the nest was removed and both this glass slide and the rest of the nest were placed in a new clean Petri dish. Any remaining workers were also moved from the old to the new Petri dish with a fine brush. At the same time, a new identical nest was placed in the same dish, with its entrance 10 cm from the entrance of the old nest. Above the new nest, a digital video camera with high colour resolution (Panasonic NV-MX500 3CCD) was set up. The interior of the new nest was filmed from the start of the experiment (destroying the old nest) until the last brood item had been carried into the new nest. The overall median duration from the start of the experiment to the last brood transport was 176 min. The videos were then analysed to identify which ants entered the new nest with or without a brood item and which ants entered carrying another adult ant. This information was used to determine how many ants scouted (entered the nest walking but not carrying before brood carrying had begun), how many ants carried brood items or other adult ants and how many ants were carried into the new nest. The time of the first discovery (first ant entering), the first brood transport (and how many ants were in the nest at the first brood transport = the “quorum threshold”) and the time of the last brood transport (end of the emigration) were also determined from the videos. All statistical analyses were performed with Minitab 14.

Results

Emigration process

All colonies emigrated completely into the new nest. As in previous studies (Mallon et al. 2001; Pratt et al. 2002; Franks et al. 2003a; Dornhaus and Franks 2006), three phases of the emigration could be distinguished: the discovery phase, the decision-making or recruitment phase and the transport phase (Table 1). We define these phases as follows: During the first phase, ants explore the arena until the new nest is discovered (the first ant entering the new nest marks the end of the discovery phase). Ants that have discovered the new nest may then continue exploring or start recruiting to the nest (decision-making phase). As soon as a quorum (a certain minimum number) of ants is present in the new nest, these ants switch from tandem running to carrying items from the old nest to the new one. The first such transport of a brood item marks the beginning of the transport phase. In the present study, the time to first discovery was not significantly different between large and small colonies, and neither was the duration of the decision-making phase (from the first discovery to the first brood transport) or the duration of the transport phase (first to last brood transport; all results in Table 1). Unlike previous studies (Dornhaus and Franks 2006; Franks et al. 2006a), we thus did not find differences in the duration of the different phases of the emigration between small and large colonies. However, this may not be surprising given that a much smaller sample size was used here and given that the new nest was only a short distance from the old nest, making discovery an easy task even with few scouts.

Workers participating in the emigration

Worker ants can either be active or passive during the emigration. We define active workers as those who engage in the emigration process by independently discovering the new nest (entering without carrying or being carried) or by carrying brood items or other adult ants to the new nest or both. Ants that independently walk to the new nest, but never carry anything, are thus also ‘active’. Passive workers remain in the old nest until they are carried to the new nest and do not become active carriers. Note that tandem runs are not included in this analysis, because they often terminate before reaching the new nest, and this may not have been captured on the video. However, previous work shows that most tandem runners (both leaders and followers) usually become active carriers later in the emigration and that few if any tandem runs take place at short emigration distances like this (Pratt et al. 2002; Franks et al. 2003a). Not all adult ants actively participate in the emigration in either large or small colonies: A median (across colonies) of 58% of all workers in large and 31% of all workers in small colonies were active (Mann–Whitney U test, p = 0.055, N 1,2 = 7, W = 68). Most of the ants that participated in transport in small colonies carried both brood and adults; the proportion of transporters that only carried brood (never adults) is higher in large colonies (32% of carriers, 7% of total number of workers) than in small colonies (14% of carriers, 3% of total workers; Table 2; Fig. 1). Not many workers carry only adult ants and never any brood items in any of the colonies (Table 2). Since most items carried are brood, this may potentially be a result of carriers choosing the item to carry at random.

The proportion of active ants (ants taking part in the emigration by scouting or carrying or entering the nest by themselves) and of passive ants (not scouting or carrying and arriving in the new nest by being carried) out of all marked ants recorded (total 1,149 in large, 412 in small colonies). Note that in the text and in tables, the medians of proportions across colonies are given, which is not necessarily the same as the proportion out of all ants recorded as shown here. More ants specialise on carrying brood in larger colonies, and more ants are passive in small colonies. Ants that are ‘active but not carrying’ are those that enter the new nest independently, without being carried, at least once (e.g. when scouting)

The most striking difference between large and small colonies is that far fewer of the adults in a large colony get carried to the new nest (35% of all adults compared to 72% in small colonies; Table 2). Since the proportion of workers that are ‘active’ is similar in large and small colonies, this implies that many ants that are initially carried to the new nest will later become active and contribute to transport (e.g. 72% of adults carried, 69% adults ‘passive’ in small colonies means that some ants were carried but not ‘passive’). The higher proportion of adults carried in small colonies cannot be explained by the presence of more brood to carry in large colonies: In fact, larger colonies had fewer brood items that needed to be carried per worker (see worker/brood ratio in Materials and methods) and also per carrier: a median of 9.4 brood items per carrier in large colonies compared to 12.1 brood items per carrier in small colonies. Since there was no significant difference in the length of the transport phase between small and large colonies (Table 1), the result can also not be explained by the hypothesis that in large colonies, passive ants have more time to become active and find their own way to the new nest.

Workload per individual

Ants that carried brood or adults to the new nest had a lower workload in larger colonies, carrying only a median of 7 items compared to 11 items per carrier in small colonies (Table 3; for a frequency distribution see Figs. 2 and 3). The busiest carrier, i.e. the ant that performed most transports, transported a median (across colonies) of about 40 items in both large and small colonies, although the maximum transported was 98 items (by an ant in a small colony; Table 3). Due to the larger total number of transported items in large colonies, this meant that the busiest ant performed a median of 11% of the transports in large colonies but 18% of those in small colonies (Table 3; Fig. 4). In general, a higher proportion of the transportation effort was made by a smaller proportion of ants in smaller colonies (Fig. 4).

Percentage of all items carried that are transported by the busiest carrier (i.e. the ant that carried most items) for each colony, relative to colony size. In smaller colonies, the busiest carrier makes a relatively larger contribution to total transportation (Spearman rank correlation: p = 0.001, r = 0.77)

Frequency histogram of how much was carried by how many ants in small and large colonies in relative terms. In large colonies, a large number of ants carry few items each. In small colonies, a large proportion of the items are transported by a few ants. Bins are >0–1%, >1–2.5%, >2.5–5% etc. Ants that do not carry are not shown here (69% in large, 77% in small colonies)

Colony-level transport rate

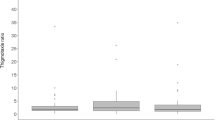

In addition, transporters in small colonies transported more items per unit time. In other words,

was higher for smaller colonies (Table 3; Fig. 5). By ‘transport phase’, we mean the colony-level duration of the transport phase as reported in Table 1; equally, ‘number of transporting ants’ and ‘total number of items transported’ are colony-level characteristics (see Tables 2 and 3).

Total number of items transported in the emigrations divided by the number of ants transporting and the duration of the transport phase. In small colonies, significantly more items per ant and time are transported (for stats, see Table 3). Shown are medians, interquartile intervals and ranges across the seven large and seven small colonies

Collective behaviour during the emigration

We found a significant difference in the quorum threshold used, i.e. the number of ants that need to be in the new nest before carrying is initiated (Mallon et al. 2001; Pratt et al. 2002). This has been found previously in some cases (Dornhaus and Franks 2006; Franks et al. 2006a). It had been suggested that ants may measure the relative quorum threshold (number of ants in the new nest [before carrying begins] divided by total number of workers in the colony; Dornhaus and Franks 2006). Indeed, this relative quorum is remarkably similar between large (0.034) and small (0.035) colonies (Table 1).

The timing of the transport of the queen seems not to be influenced by colony size. The serial position of the queen in the sequence of items carried to the new nest was not significantly associated with colony size (Spearman rank correlation of serial position against number of workers: p = 0.53, r = 0.0, n = 14) or with the total number of items carried (p = 0.59, r = 0.0). There was also no significant relationship between colony size and the number of adults present in the new nest when the queen arrives (p = 0.44, r = 0.0). The actual time as well as the proportional time of the queen’s arrival were not significantly associated with colony size (p = 0.90, r = 0.0 and p = 0.26, r = 0.2, respectively). However, the time of her arrival was correlated with the time of peak activity (highest rate of transports per 5 min), after an overall median of 110 min after the start of the emigration (Fig. 6; p = 0.001, r = 0.8). As the queen was transported, a median of 27 workers were present in the new nest (some, but not all of which had been transported there), after a median of 16 transport acts or a median of 52 min of transport phase. At this time, 44% (large colonies) or 51% (small colonies) of the total time required for the emigration had elapsed.

Discussion

What is the effect of large group size in self-organised groups? Individuals in larger social insect colonies are usually thought to be more specialised (Anderson 1999; Anderson and McShea 2001; Gautrais et al. 2002; Thomas and Elgar 2003), and, hence, individual workers in larger colonies may be able to become more efficient at their tasks. Larger colonies have also been thought to be able to afford lower individual effort or more inactive workers (Oster and Wilson 1978; Herbers 1981; Houston et al. 1988). We show that this may not apply in the context of emigration behaviour in the ant T. albipennis. In our study, worker effort (in terms of number of items carried) was indeed higher in smaller colonies, but at the same time, there was more skew in workload distribution, and, thus, most individuals contributed little to group effort. Small colonies performed more efficiently at the task of transporting colony members to a new nest (in terms of number of items transported per worker per time). In larger colonies, a smaller number of workers had to be carried; this could also be argued to be a sign of efficiency. However, it is not clear that walking rather than being carried is necessarily a benefit to the colony—carrying may or may not be more energy efficient. Indeed, the number of trips that have to be made for adult translocation is the same: Regardless of whether an ant walks or is carried, one trip needs to be made for each ant to get it to the new nest. On the other hand, in our experiment, active workers transported more items per worker in small colonies and thus were more ‘hard working’. This may be in accordance with modelling studies predicting higher individual effort in smaller colonies (Houston et al. 1988). Alternatively, the higher proportion of brood items in small colonies may require more specialised ‘nurse’ workers, which may be unable to navigate outside the nest, and therefore have to be carried. Our results thus demonstrate that general predictions on the effect of group size on colony organisation may not apply to all species and that details of the collective behaviour in question matter.

Our results also show that ‘key individuals’ matter more in smaller groups. In large colonies, the transportation effort in emigrations was more evenly distributed among all the ants that carry any items than in small colonies. In small colonies, a small proportion of ants, often a single ant, performed a large proportion of the necessary transports of brood and adults to the new nest. Individuals who perform a disproportionate amount of work compared to their nestmates may be called ‘elites’ or ‘key individuals’ (Hölldobler and Wilson 1990; Robson and Traniello 1999); the highly active workers in our study are the ‘performer’ type of key individuals according to Robson and Traniello (1999). What are the benefits associated with ‘key individuals’? Or in other words, why do not all ants contribute actively in an emigration? It may be that reliance on some key individuals with high workload has advantages. For example, extensive experience may allow these key individuals to become better at transporting because they have a chance to learn the location of the new nest and optimise their path to it. Learning has been shown to influence emigration efficiency in these ants (Langridge et al. 2004, 2008a, b) and potentially to have a larger effect in small colonies (Dornhaus and Franks 2006). Alternatively, small colonies may be at an advantage because proportionately more adults are carried and do not have to slowly find their own way to the new nest. Social carrying is indeed a faster process than other recruitment methods such as tandem running (Pratt et al. 2002). Smaller colonies are predicted to be more risk averse and may therefore invest more in improving individual performance compared to large colonies (Herbers 1981). This may be achieved by employing only a few highly experienced individuals to perform a task as shown here. Large colonies may instead rely more on probabilistic behaviours performed by many individuals (Anderson and McShea 2001). However, our results are also consistent with the interpretation that individuals in larger colonies are simply on average older and more experienced. Temnothorax ants are extremely long lived (workers may live for several years; Sendova-Franks personal communication), and if colonies are founded by single queens, larger colonies may be older and contain older workers. In more experienced colonies, fewer adults are carried (Langridge et al. 2008a), and discovery of new nests is faster (Dornhaus and Franks 2006), just as in our larger colonies.

It seems that ‘key individuals’, performing a large proportion of the work in a task, are not uncommon, especially in colony emigrations (Robson and Traniello 1999) and other brood transport (Tschinkel 1992). Is it only experience that distinguishes these individuals from their nestmates (Ravary et al. 2007)? Do individuals change their behaviour in larger colonies, or are the differences we observed here ‘emergent’ consequences of the larger group size? In a previous study, we showed that natural colonies of different group sizes are likely to differ in ways other than number of workers, possibly because of their different colony age or history (Dornhaus and Franks 2006). These difficult questions will require even more detailed, long-term observation of individuals, and manipulative studies.

In general, when analysing task allocation, it is important to distinguish ‘specialisation’ from task ‘intensity’ or workload. Specialisation is usually defined as a restriction in task repertoire (i.e. a reduced number of different tasks performed), as in ecology, a dietary specialist is defined as having a restricted diet (although there seems to be some confusion about this in the literature; see Robson and Traniello 1999; Anderson and McShea 2001; Jeanson et al. 2007). A specialist may use a different task selection rule than a generalist and thus repeatedly choose the same task. However, workload per se, i.e. the amount of time worked in a particular task or the number of times a task is executed, does not allow us to conclude that the individual in question is a specialist (according to the definition above)—both a generalist and a specialist could be highly active workers or ‘key individuals’ in one or all tasks they are performing. Do the highly active individuals in the emigrations studied here also perform a disproportionate amount of work in other tasks (making them general-purpose ‘elites’, but not specialists)? To answer this question, the activity of workers in different tasks has to be compared. We are planning to tackle this problem in the future.

References

Anderson C (1999) Task partitioning in insect societies. I. Effect of colony size on queuing delay and colony ergonomic efficiency. Am Nat 354:521–535

Anderson C, McShea DW (2001) Individual vs. social complexity, with particular reference to ant colonies. Biol Rev 76:211–237

Beckers R, Goss S, Deneubourg JL, Pasteels JM (1989) Colony size, communication and ant foraging strategy. Psyche 96:239–256

Beekman M (2004) Comparing foraging behaviour of small and large honey-bee colonies by decoding waggle dances made by foragers. Funct Ecol 18:829–835

Beekman M, Sumpter D, Ratnieks F (2001) Phase transition between disordered and ordered foraging in Pharaoh's ants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98:9703–9704

Bourke AFG (1999) Colony size, social complexity and reproductive conflict in social insects. J Evol Biol 12:245–257

Bouwma AM, Nordheim EV, Jeanne RL (2006) Per-capita productivity in a social wasp: no evidence for a negative effect of colony size. Insectes Soc 53:412–419

Buhl J, Gautrais J, Deneubourg J-L, Theraulaz G (2004) Nest excavation in ants: group size effects on the size and structure of tunneling networks. Naturwissenschaften 91:602–606

Burkhardt J (1998) Individual flexibility and tempo in the ant, Pheidole dentata, the influence of group size. J Insect Behav 11:493–505

Cole B (1986) The social behavior of Leptothorax allardycei (Hymenoptera, Formicidae): time budgets and the evolution of worker reproduction. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 18:165–173

Dornhaus A, Franks NR (2006) Colony size affects collective decision-making in the ant Temnothorax albipennis. Insectes Soc 53:420–427

Dornhaus A, Franks N, Hawkins RM, Shere HNS (2004) Ants move to improve—colonies of Leptothorax albipennis emigrate whenever they find a superior nest site. Anim Behav 67:959–963

Dornhaus A, Klügl F, Oechslein C, Puppe F, Chittka L (2006) Benefits of recruitment in honey bees: effects of ecology and colony size in an individual-based model. Behav Ecol 17:336–344

Fewell J, Ydenberg R, Winston M (1991) Individual foraging efforts as a function of colony population in the honey bee, Apis mellifera L. Anim Behav 42:153–155

Franks NR, Partridge LW (1993) Lanchester battles and the evolution of combat in ants. Anim Behav 45:197–199

Franks N, Dornhaus A, Fitzsimmons J, Stevens M (2003a) Speed vs. accuracy in collective decision-making. Proc R Soc B 270:2457–2463

Franks N, Mallon E, Bray HE, Hamilton MJ, Mischler TC (2003b) Strategies for choosing between alternatives with different attributes: exemplified by house-hunting ants. Anim Behav 65:215–223

Franks NR, Hooper J, Webb C, Dornhaus A (2005) Tomb evaders: house-hunting hygiene in ants. Biol Lett 1:190–192

Franks NR, Dornhaus A, Best CS, Jones EL (2006a) Decision-making by small and large house-hunting ant colonies: one size fits all. Anim Behav 72:611–616

Franks NR, Dornhaus A, Metherell BG, Nelson TR, Lanfear SAJ, Symes W (2006b) Not everything that counts can be counted: ants use multiple metrics for a single nest trait. Proc R Soc Biol Sci 273:165–169

Franks NR, Dornhaus A, Hitchcock G, Guillem R, Hooper J, Webb C (2007a) Avoidance of conspecific colonies during nest choice by ants. Anim Behav 73:525–534

Franks NR, Hooper J, Dornhaus A, Aukett PJ, Hayward AL, Berghoff S (2007b) Reconnaissance and latent learning in ants. Biol Lett 274:1505–1509

Gautrais J, Theraulaz G, Deneubourg JL, Anderson C (2002) Emergent polyethism as a consequence of increased colony size in insect societies. J Theor Biol 215:363–373

Gordon DM, Mehdiabadi NJ (1999) Encounter rate and task allocation in harvester ants. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 45:370–377

Herbers JM (1981) Reliability theory and foraging by ants. J Theor Biol. 89:175–189

Herbers JM (1983) Social organization in Leptothorax ants: within and between species patterns. Psyche 90:361–386

Herbers JM, Choiniere E (1996) Foraging behaviour and colony structure in ants. Anim Behav 51:141–153

Hölldobler B, Wilson EO (1990) The ants. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA

Houston A, Schmidhempel P, Kacelnik A (1988) Foraging strategy, worker mortality, and the growth of the colony in social insects. Am Nat 131:107–114

Jeanne RL, Nordheim EV (1996) Productivity in a social wasp: per capita output increases with swarm size. Behav Ecol 7:43–48

Jeanson R, Fewell JH, Gorelick R, Bertram SM (2007) Emergence of increased division of labor as a function of group size. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 62:289–298

Jun J, Pepper JW (2003) Allometric scaling of ant foraging trail networks. Evol Ecol Res 5:297–303

Karsai I, Wenzel JW (1998) Productivity, individual-level and colony-level flexibility, and organization of work as consequences of colony size. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:8665–8669

Langridge E, Franks NR, Sendova Franks AB (2004) Improvement in collective performance with experience in ants. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 56:523–529

Langridge EA, Sendova-Franks AB, Franks NR (2008a) How experienced individuals contribute to an improvement in collective performance in ants. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 62:447–456

Langridge EA, Sendova-Franks AB, Franks NR (2008b) The behaviour of ant transporters at the old and new nest during successive colony emigrations. Behav Ecol Sociobiol (in press)

Lindauer M (1952) Ein Beitrag zur Frage der Arbeitsteilung im Bienenstaat. Z Vergl Physiol 34:299–345

London KB, Jeanne RL (2003) Effects of colony size and stage of development on defense response by the swarm-founding wasp Polybia occidentalis. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 54:539–546

Mailleux AC, Deneubourg JL, Detrain C (2003) How does colony growth influence communication in ants? Insectes Soc 50:24–31

Mallon E, Pratt S, Franks N (2001) Individual and collective decision-making during nest site selection by the ant Leptothorax albipennis. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 50:352–359

Michener CD (1964) Reproductive efficiency in relation to colony size in Hymenopterous societies. Insectes Soc 11:317–342

Möglich M, Hölldobler B (1974) Social carrying behavior and division of labor during nest moving in ants. Psyche 81:219–235

O'Donnell S, Bulova SJ (2007) Worker connectivity: a review of the design of worker communication systems and their effects on task performance in insect societies. Insectes Soc 54:203–210

Oster GF, Wilson EO (1978) Caste and ecology in the social insects. Princeton University Press, Princeton, USA

Pacala SW, Gordon DM, Godfray HCJ (1996) Effects of social group size on information transfer and task allocation. Evol Ecol 10:127–165

Plowes N, Adams ES (2005) An empirical test of Lanchester’s square law: mortality during battles of the fire ant Solenopsis invicta. Proc R Soc B 272:1809–1814

Pratt S, Mallon E, Sumpter D, Franks N (2002) Quorum sensing, recruitment and collective decision-making during colony emigration by the ant Leptothorax albipennis. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 52:117–127

Ravary F, Lecoutey E, Kaminski G, Chaline N, Jaisson P (2007) Individual experience alone can generate lasting division of labor in ants. Curr Biol 17:1308–1312

Robson SK, Traniello JFA (1999) Key individuals and the organisation of labor in ants. In: Detrain C, Deneubourg J-L, Pasteels JM (eds) Information processing in social insects. Birkhaeuser, Basel

Robson SKA, Traniello JFA (2002) Transient division of labor and behavioral specialization in the ant Formica schaufussi. Naturwissenschaften 89:128–131

Schmid-Hempel P (1990) Reproductive competition and the evolution of work load in social insects. Am Nat 135:501–526

Sorvari J, Hakkarainen H (2007) The role of food and colony size in sexual offspring production in a social insect: an experiment. Ecol Entomol 32:11–14

Strohm E, Bordon-Hauser A (2003) Advantages and disadvantages of large colony size in a halictid bee: the queen’s perspective. Behav Ecol 14:546–553

Thomas M, Elgar M (2003) Colony size affects division of labour in the ponerine ant Rhytidopodera metallica. Naturwissenschaften 90:88–92

Tibbetts E, Reeve HK (2003) Benefits of foundress associations in the paper wasp Polistes dominulus: increased productivity and survival, but no assurance of fitness returns. Behav Ecol 14:510–514

Tschinkel WR (1992) Brood raiding in the fire ant, Solenopsis invicta (Hymenoptera, Formicidae)—laboratory and field observations. Ann Entomol Soc Am 85:638–646

Wolf TJ, Schmid-Hempel P (1990) On the integration of individual foraging strategies with colony ergonomics in social insects: nectar-collection in honeybees. Behav Ecol Sociobiol 27:103–111

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the DFG (Emmy Nöther fellowship to AD), the BBSRC (grant E19832), the EPSRC (grant GR/S78674/01) and the EEB Department at the University of Arizona for funding. We also thank the undergraduate students who helped with the experiments and video analysis: David Sims, Charlotte Best and Lizzie Jones, and Liz Langridge for comments on the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: J. Traniello

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License ( https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/2.0 ), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Dornhaus, A., Holley, JA., Pook, V.G. et al. Why do not all workers work? Colony size and workload during emigrations in the ant Temnothorax albipennis . Behav Ecol Sociobiol 63, 43–51 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-008-0634-0

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00265-008-0634-0