Abstract

Purpose

Our purpose was to explore antidepressant drug (AD) prescribing patterns in Italian primary care.

Methods

Overall, 276 Italian general practitioners (GPs) participated in this prospective study, recruiting patients >18 years who started AD therapy during the enrolment period (January 2007 to June 2008). During visits at baseline and 3, 6, and 12 months, data about patients’ characteristics and AD treatments were collected by the GPs. Discontinuation rate among new users of AD classes [i.e., selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI); tricyclics (TCAs); other ADs) were compared. Logistic regression analyses were performed to identify predictors of AD discontinuation.

Results

SSRIs were the most frequently prescribed ADs (N = 1,037; 75.3 %), especially paroxetine and escitalopram. SSRIs were more likely to be prescribed because of depressive disorders (80 %), and by GPs (51.1 %) rather than psychiatrists (31.8 %). Overall, 27.5 % (N = 378) of AD users discontinued therapy during the first year, mostly in the first 3 months (N = 242; 17.6 %), whereas 185 (13.4 %) were lost to follow-up. SSRI users showed the highest discontinuation rate (29 %). In patients with depressive disorders, younger age, psychiatrist-based diagnosis, and treatment started by GPs were independent predictors of SSRI discontinuation.

Conclusions

In Italy, ADs—especially SSRIs—are widely prescribed by GPs because of depressive/anxiety disorders. Active monitoring of AD users in general practice might reduce the AD discontinuation rate.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Depressive disorders continue to be considered a common cause of disability worldwide. A 2001 World Health Organization report projected that by 2020, depression will account for more lost disability adjusted life years (DALY) than all other conditions except ischemic heart disease [1]. In this scenario, primary care physicians have a central role, as almost two thirds of patients with depression are treated with antidepressants drugs (ADs) in this setting [2]. Due to better tolerability, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and other newer ADs (e.g., venlafaxine) have tended to replace the older tricyclics in depression management in recent years. However, it has been reported that 50 % of patients stop taking ADs as early as 3 months after starting treatment, and >70 % discontinue medication before 6 months [3].This early discontinuation rate is in contrast with clinical guidelines, which recommend a continuous AD treatment in depressed patients for at least 6 months [4]. Early withdrawal of AD therapy increases the risk of relapse/recurrent depression, which accounts for most of the prevalence, burden, and cost of disease [5].

In addition to depressive disorders, ADs are frequently prescribed for treating other neuropsychiatry indications, such as anxiety, sleep disorders [6], urinary incontinence [7], headache [8], and neuropathic pain [9]. Use of ADs has constantly increased over the past decade in several Western countries [10–16]. This increase seems to be partly attributable to the wider use of SSRIs and other recently marketed ADs for treating neuropsychiatric diseases other than depressive disorders [16, 17]. On the other hand, this increase may be the result of better and earlier treatment and recognition of depressions [18].

Other retrospective investigations were carried out in Italy with the aim of analyzing the antidepressant prescribing pattern in primary care [13, 19–23], but these studies were limited by the fact that they took into account only regional data or were lacking relevant clinical information, such as indication for use. The aim of our study was to evaluate the prescribing pattern of AD use in Italian primary care in recent years. The secondary objective was to assess the rate and predictors of AD therapy discontinuation.

Methods

Study setting

This was a nationwide, prospective, observational cohort study conducted in the context of the VARIO project [24], an Italian Drug Agency-funded project supported by the Italian Societies of General Practitioners (SIMG), Pharmacology (SIF), and Psychiatry (SIP), to evaluate the use and safety of ADs in general practice. As a first step, an investigator meeting was performed at the beginning of the project with all regional coordinators of research centers [i.e., general practitioners (GPs; ambulatories). All regional coordinators were taught about all the main technical aspects concerning the study for prospective monitoring and, in particular, about the procedure for patient recruitment and data collection. Thereafter, each regional coordinator organized a meeting about the same topic with all GPs from the same catchment area who agreed to participate. In addition, a Contract Research Organization (CRO) was enrolled to supervise, coordinate, and monitor data collection from GPs. The study protocol was approved by the Local Ethical Committees for each coordinating center participating in the study.

Study population

Overall, 276 GPs distributed throughout Italy were enrolled. Among patients visiting the ambulatory centers, participating GPs selected the first five patients >18 years who were first-ever treated with ADs, irrespective of the indication of use, during the enrolment period (1 January 2007 to 1 June 2008). Patients were included whether AD treatment was likewise initiated by a GP or a specialist (in this case, passing by GP a to get the prescription reimbursed by the National Health System). Patients residing in nursing homes or long-term care, those unable to provide informed consent, and the terminally ill were not included.

Study drugs

Use of the following AD classes was explored: (a) SSRIs (ATC: N06AB); (b) TCAs (N06AA); (c) others (venlafaxine, N06AX16; reboxetine, N06AX18; mianserin, N06AX03; mirtazapin, N06AX11; trazodone, N06AX05, nefazodone, N06AX06; duloxetine, N06AX21; bupropion, N06AX12; and combinations with antipsychotics, e.g., perphenazine/amitriptyline). Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAO) inhibitors, which are poorly used in Italy, were not included.

Data collection

All patients in the study were followed for up to 12 months. Their demographic and clinical characteristics, with specific focus on AD therapy (e.g., indication for use, adhering to treatment, change in dosing regimen, reason for discontinuation) over time were measured by GPs at the time of recruitment and after 3, 6, and 12 months from the baseline visit. Through patient interview at the baseline visit, GPs collected information concerning covariates that cannot be generally retrieved in claims and electronic medical record databases, such as :

-

1.

Cigarette smoking:

-

(a)

current, if the patient was a regular smoker at the start of the study;

-

(b)

occasional, if the patient smoked no more than one cigarette per day and not every day at the start of the study;

-

(c)

former, if the patient stopped smoking time prior to the start of the study;

-

(d)

never smoker.

-

(a)

-

2.

Marital status (unmarried, married/cohabiting, separated/divorced, widowed)

-

3.

Education (illiterate, primary, middle, high school diploma, academic degree)

-

4.

Profession (unemployed, homemaker, looking for first job, publicly employed, retired, student worker, student)

-

5.

Physical activity (absent, light, normal, heavy; based on Physical Activity Level classification)

-

6.

Body Mass Index (BMI; as derived from the formula weight/height2)

-

7.

Alcohol consumption (yes, no).

GPs also asked patients if they were currently receiving other therapies (e.g., psychotherapy, alternative medicines such as homeopathics and herbal remedies) for the same indication of use of antidepressants. During the first 3 months, patients were contacted on a biweekly basis by GPs for information on any eventual harmful effect or other issues related with AD treatment. Whether AD treatment was initiated by a GP or a specialist (e.g., neurologist, psychiatrist) was also recorded. At baseline and follow-up visits, all information was collected by each participating GP through electronic, structured questionnaires by both revising healthcare data (e.g., drug prescription and medical diagnoses) from their electronic registries or, if necessary, interviewing the patient. All clinical diagnoses and medications were respectively coded using the International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD9-CM) and the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system. The anonymized data were all finally gathered in a central database using Microsoft Office Access 2007.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square test for categorical variables and Student’s t test for continuous variables were used for comparing demographic and clinical characteristics of different antidepressant types (SSRI vs. tricyclics and others) included in the analysis. For each molecule and class and switching (i.e., substitution of the used AD with another one) and discontinuation (i.e., stopping all ADs) rates within 3, 6, and 12 months were measured. Kaplan–Meier survival curve and log-rank test were produced to identify any statistically significant difference in adherence to treatment among various AD classes. Multivariate Cox proportional hazard model was used to assess the independent predictors of AD class-specific treatment discontinuation in patients with depressive disorders. All statistical analyses were conducted in SPSS/PC, Version 15 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The level of significance for all statistical tests was set at p value < 0.05.

Results

Overall, 1,377 new AD users were included in the study by 276 GPs. Three GPs recruited only four patients each. All the new AD users eligible for inclusion in the study and contacted agreed to participate. SSRIs were the most frequently prescribed ADs as first prescription (N = 1,037; 75.3 %), followed by other ADs (N = 275; 19.9 %) and TCAs (N = 65; 4.8 %). At baseline, the main characteristics were similar among the three different AD users (Table 1). Mean age of AD users was 52 years; 71.5 % were women. Most AD users were homemakers (31.1 %), married or cohabiting (60.4 %), and with a high level of education (44.2 % with high school/academic degree). Around one third of AD users were current or former smokers and alcohol consumers. More than half of AD users were overweight or obese (53.5 %), and a high proportion of them did not practice any physical activity (41.7 %). Statistically significant differences among new users of various AD types were reported only for body mass index (BMI) (P value = 0.028), with TCAs having the highest proportion of obese patients (23.3 %) and other ADs with the highest proportion of underweight patients (4.7 %). At baseline, almost all AD users received monotherapy (95.1 %). As regards indication for use, approximately 80 % of AD users were treated for depressive disorders. Distribution of AD use significantly varied among different indications of use: compared with other AD classes, TCAs were less likely to be prescribed for treating depression (66.2 % vs 80.2 % for SSRI and 82.5 % for other ADs) and more likely for headache and neuropathic pain (15.4 % vs. 3.0 % and 3.2 %, respectively) compared with other AD classes. Overall, 26.5 % of AD users reported anxiety disorders as the main indication for use (from 21.5 % of TCAs users to 27.2 % of SSRI users). Approximately 30 % of patients were diagnosed with multiple psychiatric disorders (i.e., depression, affective psychosis, anxiety). As regards other therapeutic treatments, 7.8 % (N = 102) of AD users also received psychotherapy, whereas 8.0 % (N = 111) reported the use of alternative medicine (e.g., herbal remedies, homeopathics, dietary supplements). Among total AD users and those treated because of depressive disorders, 184 (13.3 %) and 103 (9.3 %), respectively. were concomitantly treated with antipsychotics.

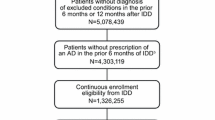

Figure 1 shows the distribution of AD prescriber type. Overall, most AD users (51.1 %) and, in particular, users of SSRIs (55.4 %), were mainly treated by GPs, followed by psychiatrist working in the public sector (19.2 %). TCAs were prescribed in equal proportions by GPs and psychiatrists.

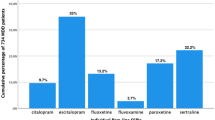

As regard single molecules, paroxetine (N = 356; 25.9 % of total ADs) and escitalopram (N = 253; 18.4 %) were the most frequently prescribed medications among SSRIs. venlafaxine use was 11.6 % (N = 160; and duloxetine 5.6 % among other ADs; clomipramine use was 2.0 % (N = 27) among TCAs (data not shown).

At the end of 1 year of follow-up, overall, 185 (13.4 %) AD users were lost, and of those mostly occurred in the first 3 months of therapy (N = 163, 88.8 %). A slightly lower proportion of patients was lost to follow-up among TCA users (10.4 %) compared with SSRI (13.0 %) and other AD users (15.8 %). Among depressed patients specifically, 14.1 % of AD users were lost to follow-up. On the other hand, 378 (27.5 %) users discontinued any AD treatment during the 1-year follow-up, with a slightly higher proportion among SSRI users (28.7 %), as shown in Fig. 2. The highest rate of discontinuers was observed within the first 3 month from the beginning of the therapy (17.6 %). Most discontinuers (32.5 %) withdrew treatment voluntarily, whereas 14 % stopped therapy because they were judged by the physician to be recovered. No statistically significant difference was observed in adherence to treatment over the first year of follow-up among various AD classes.

In addition, in the first 3 months, 30 patients (2.2 %) switched between two different ADs, whereas daily dosage was adjusted for 18 (1.3 %) users (data not shown). Looking at single molecules, the highest discontinuation rate was found for fluoxetine (33.3 %) and paroxetine (31.5 %) among SSRIs, amitriptyline (34.6 %) among TCAs, and trazodone (27.3 %) among other ADs (data not shown). Among SSRI users with depressive disorders, in general, being a student hazard ratio (HR) 2.50, 95 % confidence interval (CI) 1.03–6.09, P value = 0.044) and a younger age seem to be associated with higher risk of AD treatment discontinuation. In particular, older users of SSRI (65–80 years) showed a tendency toward a lower risk for drug withdrawal during the first year of treatment compared with younger patients (0.51, 0.27–0.98, P value = 0.004). In addition, diagnosis made by psychiatrists (2.18, 1.15–3.88, P value = 0.001) was an independent predictors of SSRI discontinuation, whereas treatment prescribed directly by a psychiatrist had a lower risk of being discontinued compared with those prescribed by GPs (0.45, 0.24–0.84, P value = 0.041) (Table 2). Among users of other ADs, obese patients (0.25, 0.07-0.92, P value = 0.046) were at lower risk of treatment discontinuation compared with those with normal weight.

Discussion

This nationwide, population-based, observational, prospective study analyzed the prescribing patterns of ADs in Italian primary care in recent years. As with previous studies, we observed that women, patients aged 45–64, patients who are married, and patients with higher education are most likely to be treated with ADs, consistently with increased diagnoses of depression and anxiety disorder in these groups of patients [17, 21]. We found that SSRIs represent the most commonly prescribed AD class (75.3 %). This data is in line with other previous Italian and European investigations [13, 16, 19, 23]. The trend of SSRI use can be partially explained by the fact that SSRIs show a better tolerability and safety profile and can be administered once daily, and there is lower need for dose titration. However, the use of SSRIs in special patient categories (e.g., elderly) should be particularly monitored in light of emerging safety issues, such as bleeding and hyponatremia [25].

We found that SSRIs were mainly prescribed by GPs (51 %) for depressive and anxiety disorders. These results are in line with data from a population-based study in Norway [26], where GPs were identified to have a key role in the initiation of AD treatment. By contrast, Belgian psychiatrists prescribe ADs to a larger proportion of their patients with depression compared with GPs [12]. This intercountry heterogeneity may reflect significant differences in healthcare structure and services across European countries. Due to the complexity of psychiatric disorder diagnosis and management, the possibility of misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment may be higher if a patient visits a GP rather than a psychiatrist. Another interesting finding was that the highest proportion of obese patients was observed among new users of TCAs, despite the fact these medications are well known to be associated with weight gain.

Considering single molecules, paroxetine (25.9 %) and escitalopram (18.4 %) were the most frequently prescribed medications among SSRIs. This findings is consistent with a national Italian report on drug consumption in 2010 [27], in which paroxetine (7.5 DDD/1,000 inhabitants), escitalopram (6.8 DDD/1,000 inhabitants), and sertraline (5.7 DDD/1,000 inhabitants) were reported as the most frequently used ADs. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of ADs suggests that escitalopram and sertraline might be the best choice when starting treatment for moderate to severe major depression [28]. According to that study, these two ADs have the best possible balance between efficacy, safety, and acceptability. Escitalopram is one the two ADs (the other is duloxetine) still on patent in the USA and Europe. Sertraline might be considered an even better option than escitalopram due to its lower cost, despite a properly designed cost–benefit analysis not yet having been performed [28].

By the end of 1 year of follow-up, 27.5 % AD users treated for depressive disorders discontinued any treatment. In addition, 14.1 % of AD users with depressive disorders were lost to follow-up during the 1-year follow-up, and we cannot rule out that these patients may have discontinued treatment. As suggested by current guidelines, for treating the acute phase of depressive disorders, a period of 4–6 weeks up to a maximum of 10 weeks is recommended. For preventing relapses, however, further continuation of treatment varying from 4 to 12 months is indicated [29]. Nonetheless, early withdrawal of AD treatment has been observed in previous retrospective studies, which documented even higher AD discontinuation rates than observed in our study: from 30 % within 8 weeks in a Dutch study [30] to 42.4 % during the first 30 days in US data [31]. Although some previous studies reported similar early discontinuation rates [32, 33], our study documents overall a lower rate of discontinuation that previously observed estimates in other retrospective studies [34, 35]. The observed finding in our prospective study may be due to the active and intensive monitoring with several contacts and follow-up visits during the initial phases of the AD therapy. Greater adherence to AD treatment may have a beneficial effect in terms of preventing relapses and recurrent episodes of depressive disorders.

In this study, approximately two thirds of discontinuers stopped treatment voluntarily and/or no longer visited their GP for follow-up visits, thus emphasizing the need to put even more effort into explaining to patients in whom treatment is initiated the potential benefits, risks, and tolerability issues concerning ADs. With respect to predictors of treatment withdrawal, we found that SSRI users directly treated by psychiatrists had lower risk of drug discontinuation. This data is confirmed by Meijer et al., who identified the being treated by a psychiatrist was the best predictor of becoming a long-term user. Compared with GPs, psychiatrists may be more aware of and adhere more frequently to clinical practice guidelines and additionally might treat a greater number of patients with more severe depression; such patients are usually more compliant to AD treatment [30]. On the other hand, Van Geffen et al. documented that the potential value of AD prescription by GPs is more likely to be underestimated by patients with nonspecific and minor conditions, typically diagnosed by GPs, such as feeling depressed, sleeping problems, fatigue, or relationship problems [36]. Another reason for AD discontinuation generally is the initial and inappropriate prescribing of ADs to patients with vague symptoms, who may not, in fact, be suffering from depression. This factor may have accounted partly for AD withdrawal in our study, as most of the patients were directly treated by GPs, who are less skilled than psychiatrist for diagnosing and treating accurate depression. However, we did not have the opportunity to explore this issue. Interestingly, 8 % of AD users also take herbal medicines and other alternative medications. Due to the uncertainty of beneficial effects and potential risk of serious pharmacological interactions with antidepressants [15], both GPs and psychiatrists should inquire about the use of alternative remedies and warn AD users of the potential effects and interaction risks.

There are certain strengths and limitations to this study. First, it was possible to evaluate the most relevant demographic and clinical characteristics of AD users. In particular, some characteristics (e.g., cigarette smoking and alcohol consumption, use of alternative medicines, type of prescribers) cannot be properly assessed using other sources, such as healthcare databases. This survey was conducted with active support from SIMG, which facilitated the active participation of general practitioners. Nevertheless, some limitations warrant caution when interpreting our study results. The use of AD was assessed based on prescriptions and questions to the patients, and no information was provided as to whether the prescriptions were actually filled and the ADs taken. Although it was unlikely that patients coming to a follow-up visit were noncompliant with drug therapy, a slight overestimation of AD discontinuation rate cannot be totally ruled out. Information about characteristics of AD users was occasionally missing, but his was randomly distributed across different AD classes. We included in the study only patients who had never been treated with ADs. GPs asked this question explicitly to all patients who met elegibility criteria. Nevertheless, we cannot rule out that some patients, especially the elderly, had been treated years earlier with ADs but could not correctly recall. This limitation is unlikely to significantly affect the main findings. Finally, the longest follow-up was 1 year, thus limiting the generalizability of the study results.

Conclusions

In conclusion, this study shows that in recent years, ADs—and in particular, SSRIs—are mainly prescribed in Italy by GPs and are primarily prescribed to treat depressive and anxiety disorders. Due to frequent early discontinuation of AD treatment, careful monitoring of patients newly treated with ADs, especially in the first weeks of treatment, is highly recommended. This study supports the idea that active and intensive patient monitoring may reduce the rate of early discontinuation of AD therapy in general practice.

References

Haden ACB (2001) The world health report 2001.Mental health: new understanding, new hope. World Health Organization, Geneva, 30.2001

Sturm R, Meredith LS, Wells KB (1996) Provider choice and continuity for the treatment of depression. Med Care 34:723–734

Pomerantz JM, Finkelstein SN, Berndt ER, Poret AW, Walker LE, Alber RC et al (2004) Prescriber intent, off-label usage, and early discontinuation of antidepressants: a retrospective physician survey and data analysis. J Clin Psychiatry 65:395–404

Isacsson G, Boethius G, Henriksson S, Jones JK, Bergman U (1999) Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have broadened the utilisation of antidepressant treatment in accordance with recommendations. Findings from a Swedish prescription database. J Affect Disord 53:15–22

Kuyken W, Byford S, Byng R, Dalgleish T, Lewis G, Taylor R et al Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial comparing mindfulness-based cognitive therapy with maintenance anti-depressant treatment in the prevention of depressive relapse/recurrence: the PREVENT trial. Trials 11:99

Walsh JK (2004) Pharmacologic management of insomnia. J Clin Psychiatry 65(Suppl 16):41–45

Zinner NR, Koke SC, Viktrup L (2004) Pharmacotherapy for stress urinary incontinence: present and future options. Drugs 64:1503–1516

Colombo B, Annovazzi PO, Comi G (2004) Therapy of primary headaches: the role of antidepressants. Neurol Sci 25(Suppl 3):S171–S175

Maizels M, McCarberg B (2005) Antidepressants and antiepileptic drugs for chronic non-cancer pain. Am Fam Physician 71:483–490

Ufer M, Meyer SA, Junge O, Selke G, Volz HP, Hedderich J et al (2007) Patterns and prevalence of antidepressant drug use in the German state of Baden-Wuerttemberg: a prescription-based analysis. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 16:1153–1160

Svab V, Subelj M, Vidmar G Prescribing changes in anxiolytics and antidepressants in Slovenia. Psychiatr Danub 23:178–182

Demyttenaere K, Bonnewyn A, Bruffaerts R, De Girolamo G, Gasquet I, Kovess V et al (2008) Clinical factors influencing the prescription of antidepressants and benzodiazepines: results from the European study of the epidemiology of mental disorders (ESEMeD). J Affect Disord 110:84–93

Trifiro G, Barbui C, Spina E, Moretti S, Tari M, Alacqua M et al (2007) Antidepressant drugs: prevalence, incidence and indication of use in general practice of Southern Italy during the years 2003–2004. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf 16:552–559

Avorn J (2001) Improving drug use in elderly patients: getting to the next level. JAMA 286:2866–2868

Weissman J, Meyers BS, Ghosh S, Bruce ML (2011) Sociodemographic and clinical factors associated with antidepressant type in a national sample of the home health care elderly. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 33:587–593

Bauer M, Monz BU, Montejo AL, Quail D, Dantchev N, Demyttenaere K et al (2008) Prescribing patterns of antidepressants in Europe: results from the Factors Influencing Depression Endpoints Research (FINDER) study. Eur Psychiatry 23:66–73

Zimmerman M, Posternak M, Friedman M, Attiullah N, Baymiller S, Boland R et al (2004) Which factors influence psychiatrists’ selection of antidepressants? Am J Psychiatry 161:1285–1289

Rich CL, Isacsson G (1997) Suicide and antidepressants in south Alabama: evidence for improved treatment of depression. J Affect Disord 45:135–142

Percudani M, Barbui C, Fortino I, Petrovich L (2004) Antidepressant drug use in Lombardy, Italy: a population-based study. J Affect Disord 83:169–175

Poluzzi E, Motola D, Silvani C, De Ponti F, Vaccheri A, Montanaro N (2004) Prescriptions of antidepressants in primary care in Italy: pattern of use after admission of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for reimbursement. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 59:825–831

Guaiana G, Andretta M, Griez E, Biancosino B, Grassi L Sales of antidepressants, suicides and hospital admissions for depression in Veneto Region, Italy, from 2000 to 2005: an ecological study. Ann Gen Psychiatry 10:24

Balestrieri M, Carta MG, Leonetti S, Sebastiani G, Starace F, Bellantuono C (2004) Recognition of depression and appropriateness of antidepressant treatment in Italian primary care. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 39:171–176

Castelpietra G, Morsanutto A, Pascolo-Fabrici E, Isacsson G (2008) Antidepressant use and suicide prevention: a prescription database study in the region Friuli Venezia Giulia, Italy. Acta Psychiatr Scand 118:382–388

Evaluation of prescribing pattern and safety profile of antidepressant and antipsychotic medications in Italian general practice

Spina E, Trifiro G, Caraci F Clinically significant drug interactions with newer antidepressants. CNS drugs 26:39–67

Kjosavik SR, Hunskaar S, Aarsland D, Ruths S (2011) Initial prescription of antipsychotics and antidepressants in general practice and specialist care in Norway. Acta Psychiatr Scand 123:459–465

Agenzia Italiana del Farmaco A (2010) Rapporto gennaio-settembre 2010

Cipriani A, Furukawa TA, Salanti G, Geddes JR, Higgins JP, Churchill R et al (2009) Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 12 new-generation antidepressants: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. Lancet 373:746–758

Anderson IM, Ferrier IN, Baldwin RC, Cowen PJ, Howard L, Lewis G et al (2008) Evidence-based guidelines for treating depressive disorders with antidepressants: a revision of the 2000 British Association for Psychopharmacology guidelines. J Psychopharmacol (Oxford, England) 22:343–396

Meijer WE, Heerdink ER, Leufkens HG, Herings RM, Egberts AC, Nolen WA (2004) Incidence and determinants of long-term use of antidepressants. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 60:57–61

Olfson M, Marcus SC, Tedeschi M, Wan GJ (2006) Continuity of antidepressant treatment for adults with depression in the United States. Am J Psychiatry 163:101–108

Andersson Sundell K, Waern M, Petzold M, Gissler M (2011) Socio-economic determinants of early discontinuation of anti-depressant treatment in young adults. Eur J Public Health

Rosholm JU, Andersen M, Gram LF (2001) Are there differences in the use of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and tricyclic antidepressants? A prescription database study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 56:923–929

Vanelli M, Coca-Perraillon M (2008) Role of patient experience in antidepressant adherence: a retrospective data analysis. Clin Ther 30:1737–1745

Hansen DG, Vach W, Rosholm JU, Sondergaard J, Gram LF, Kragstrup J (2004) Early discontinuation of antidepressants in general practice: association with patient and prescriber characteristics. Fam Pract 21:623–629

van Geffen EC, Gardarsdottir H, van Hulten R, van Dijk L, Egberts AC, Heerdink ER (2009) Initiation of antidepressant therapy: do patients follow the GP’s prescription? Br J Gen Pract 59:81–87

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the Italian Drug Agency through a national grant dedicated to pharmacovigilance projects.

Conflict of interest

None

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Trifirò, G., Tillati, S., Spina, E. et al. A nationwide prospective study on prescribing pattern of antidepressant drugs in Italian primary care. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 69, 227–236 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-012-1319-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00228-012-1319-1