Abstract

The current status of the population's bone health has caused considerable concern in the USA and around the world. In keeping with that situation, the US Surgeon General issued a special report on Bone Health and Osteoporosis in 2004 calling attention to a rapidly increasing healthcare problem especially linked to a growing and aging population base. The report specifically cited the medical profession's failure to treat the underlying osteoporosis in elderly individuals with fragility fractures with a 20% treatment rate as the norm. It was noted that an individual fracture was a sentinel event that provided a “teachable moment” for the patient in order to prevent future fractures. Additional statistics revealed the annual total number of fragility fractures, more than two million, exceeded the combined annual total incidence of stroke, myocardial infarction, and breast cancer. Realizing that the American Heart Association and the cardiology community had a successful US national program encouraging the use of beta blockers in patients after myocardial infarction in order to prevent recurrences, the American Orthopaedic Association (AOA) embarked on a course leading to the development of a program to improve bone healthcare in elderly patients with fragility fractures. The cardiology project, “Get With The Guidelines” (GWTG), included a registry in order to document improvement in cardiac patient care. Therefore, the AOA, a leadership group of orthopaedic surgeons, decided it was time to engage the orthopaedic community in a quality improvement initiative patterned after GWTG. Thus, Own the Bone was created as a multidisciplinary program in order to engage patients and physicians from different specialties who might be involved with the bone health concerns of patients with fragility fractures. After the success of a pilot study from 2005 to 2006, Own the Bone was launched as a US national quality improvement program in 2009. It involves a turnkey protocol, utilizing a web-based registry, in order to complete ten basic measures of patient care in patients 50 years and older with fragility fractures. Those measures center on information and counseling on nutrition, physical activity, lifestyle changes, diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis, and communication to the patient and primary care physician, mentioning the need for osteoporosis care. While this project was initially meant to be implemented in a hospital setting, it can also be applied in an outpatient clinic or emergency care facility. The program continues to expand to numerous hospitals in many states with the support of a growing number of orthopedists and allied medical specialists interested in bone health and osteoporosis. Thus, Own the Bone is a systems-based, quality improvement initiative which provides many benefits for patients with fragility fractures and their treating physicians.

Similar content being viewed by others

Many individuals from various medical specialties and health-related disciplines from around the world have come to realize the existence of a common problem which must be confronted—namely an increase in fragility fractures in patients with compromised skeletal health. Therefore, this presentation represents the efforts of the American Orthopaedic Association (AOA) to join the vast worldwide team of those who have great concern about the epidemic of osteoporosis and its associated fractures.

Now a comment on the history and current status of the AOA. Ours, the oldest US orthopaedic organization, is a leadership group with about 1,500 members. Currently, with an elected membership from academia as well as other areas of orthopaedic leadership, it is much smaller than our American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS), which includes about 20,000 orthopaedic surgeons who are board certified. The AOA, in fact, gave birth to the AAOS, our most significant orthopaedic journal, and other organizations. Our mission statement and vision both involve recognizing leadership to further the specialty of orthopaedics while also catalyzing the entire orthopaedic community to attain further recognition. It is with those standards as our guide that we created, and now submit to the medical community at large, our Own the Bone program, designed to prevent future fractures in those patients with current fragility fractures. “The time is now”—so we were told by the Surgeon General and Dr. Larry Raisz in 2004—to act in regard to the recognition, prevention, and treatment of osteoporosis in the population at large [1].

Some pertinent points about the evolution of Own the Bone are now in order. Many realize, but it is worth repeating, that the number of annual fragility fractures in our nation now approximates 2.1 million—more in number than the incidence of stroke, heart attack, and breast cancer combined. The yearly direct cost of those fractures now exceeds US $19 billion with a continued upward progression expected in both incidence and cost due to the ever-increasing expansion of the older adult population in this country due to the 80 million members of the “baby boom” generation. The National Osteoporosis Foundation estimates more than 50 million individuals currently have osteoporosis and low bone mass [2], noting that most fragility fractures actually occur in patients with “low bone mass.” In addition, within the next decade, the number of affected individuals with bone health deficiency will continue to grow unless we institute a major public health campaign. With our healthy, aging population, we expect a dramatic increase in vertebral and hip fractures, especially after age 70. The report of the Surgeon General outlined the importance of preventing further bone disease by identifying at-risk individuals by noting the “most important flag”—a previous fragility fracture. Encompassed in that observation is the genesis of Own the Bone.

So what actually brought us to the mission of Own the Bone? Forty years ago, the burden of coronary heart disease was predicted to overwhelm our population. The medical community has come to recognize a significant graphic representation of this projected annual incidence of death from heart disease portrayed by an upward-sloping horizontal line—suddenly changing to a rapid descending path. This graphic picture represents a precipitous decline in heart-related deaths as a result of a multiplicity of improvements in cardiac care, namely coronary artery bypass surgery, angioplasty, improved antihypertension and statin drugs, and lifestyle changes (Fig. 1). Paramount in that cardiac care arena was the recognition of the importance of beta-blocker drugs utilized in patients with myocardial infarction, in order to prevent future infarcts [3]. I submit that our current position with fragility fractures and osteoporosis is a snowball analogy. As the number of fractures grows, as a snowball pushed on level ground, it will be more difficult to control, but if we can intervene, as did the cardiology and cardiac surgery community in heart disease, we can push the snowball over the edge and let it gain mass and speed as it proceeds downhill like a descending graphic line. Our goal, therefore, is to limit the predicted explosion in future fractures.

With this knowledge as background, it is appropriate to discuss the origin of the Own the Bone program. The model for this approach was not originated by the AOA, but rather by the American Heart Association (AHA). The cardiology community had not adopted beta-blocker use on a routine basis. Thus, opportunity lost—in regard to controlling the heart disease and recurrent myocardial infarct epidemic. Enter the AHA and a quality improvement program, “Get With The Guidelines” (GWTG), in order to change physician behavior and improve the care of cardiac patients. That program, which emphasized the use of beta blockers in the scenario mentioned above, proved to be a very successful patient management tool since it represented a collaborative model with physicians and hospitals working with the AHA and a national registry to monitor physician compliance. With the aid of many AHA field representatives, the GWTG program engendered dramatic gains in the appropriate prescribed use of beta blockers, eventually leading to a physician compliance rate of more than 90%. That success was recognized by the National Committee on Quality Assurance by removal, in 2007, of that quality measure from the list of Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) measures which were targeted for major gains in quality of care improvement. An editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine, September 20, 2007, entitled, “Eulogy for a Quality Measure,” noted the success of the GWTG program [4]. At the same time, recent statistics indicate physician compliance in recommending breast cancer screening at 83% and colorectal cancer screening at 74%, while the orthopaedic and medical communities treat osteoporosis after a fracture in only 21% of cases.

With that success as a model, a number of members of the AOA felt strongly that the orthopaedic community had to make a commitment to the bone health of our patients. For years, we, as orthopedists, treated fractures without considering comprehensive treatment of the older person's skeletal health for a number of reasons. Until recently, only estrogen was available, and that was felt to be within the purview of a patient's gynecologist or internist. Then, with the arrival of multiple other treatment modalities such as the bisphosphonates and parathyroid hormone, we still did not embrace prescribing treatment or encouraging other specialties to do so [5]. There were and are two major problems—many patients deny osteoporosis as the cause of their fracture, and many orthopedists overlook or ignore it. Numerous articles in the literature in the last decade have noted these significant points. Thus, with the need for leadership and stimulation of the orthopaedic community as our mantra, a concerned group made an oral plea with a presentation at our national meeting in 2005 and followed that same year with a written position paper in the Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery (JBJS): “Leadership in Orthopaedics: Taking a Stand to Own the Bone [6].” In so doing, we noted that a so-called “minor wrist fracture” could lead to a major vertebral or hip fracture a few years later. A number of studies, including the 2004 Report of the Surgeon General and those that followed, noted that a fracture is a “sentinel event” with nearly 50% of women and 25% of men with hip fractures having sustained a previous fracture [1, 6–11]. Thus, the common scenario of fracture care followed by rehabilitation, with only a small chance of intervention by a primary care provider or osteoporosis specialist in regard to bone health treatment, led to the common cycle of future fractures with resultant postural deformity and significant change in the quality of life in older adults. Therefore, noting that the original fracture provides a “teachable moment” for the patient and the multidisciplinary care team, the concept of Own the Bone, as a pilot study to address the skeletal health of patients with fragility fractures in order to prevent future fractures, was born.

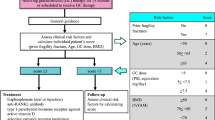

Realizing that the cycle of recurrent fractures could be broken with a multidisciplinary, all inclusive program, the AOA launched a pilot study at 14 volunteer hospital sites in order to prove that a multiphasic program could result in improved patient care in those individuals who had sustained a fragility fracture (Fig. 2). The program stressed patient education and osteoporosis care with prompts to the primary care physician and bone health team. Those 14 dedicated sites, all of which had AOA members who acted as “champions,” enrolled some 600 patients from September 2005 to August 2006 and demonstrated statistically significant improvement in evidence-based osteoporosis care guidelines with those study results published in JBJS in January, 2008 [12]. We were able to show significant improvement in multiple measures eventually included in our current program except for pharmacologic treatment at the time of fracture and the completion of bone density scans (DXA) when compared to baseline treatment rates prior to initiating the pilot study. It is worth noting though, that one of the reviewers of our January, 2008, JBJS article, prior to publication, made a pointed comment about the failure in our pharmacologic treatment initiative, noting that orthopedists prescribe NSAIDs “like candy” but are extremely reluctant to prescribe bisphosphonate drugs which cause far fewer devastating side effects than NSAIDs. With our pilot program success noted, the AOA officially launched our Own the Bone program as a quality improvement initiative in June 2009.

So, who owns the bone? The answer: everyone must take ownership in bone health with the patient as a central focus and other members of the health care team—physicians, nurses, and hospital quality assurance programs—all participating. Our program is designed to change both physician and patient behavior in order to reduce the incidence of future fractures [13–15]. Thus we endeavor to increase awareness of osteoporosis associated with a fragility fracture with the resultant evaluation and treatment of that problem as a necessary adjunct to basic fracture care. Closing the previously mentioned treatment gap is a secondary goal of our program. We have done this by designing a turn-key, multidisciplinary product that can be incorporated in routine clinical practice utilizing a web-based registry. The program includes ten basic measures in six categories designed to improve the bone health of all patients, female and male, 50 years and older with a fragility fracture. Those measures include: counseling on nutrition, physical activity, and lifestyle; diagnosis and treatment of osteoporosis; and communication vehicles for patients and primary care physicians (Table 1). Thus we hope to decrease both morbidity and mortality after an initial fracture by employing these measures which are consistent with those put forward by HEDIS and the Physician Quality Reporting Initiative (PQRI). Those PQRI measures relate to osteoporosis care by communication with a physician managing patient care after a fracture and the management of osteoporosis following a fracture of the hip, spine, or distal radius for patients 50 or older. The program is designed for implementation in a hospital setting but certainly can be instituted in an emergency department or outpatient fracture clinic setting. Ultimately, it is our hope that the measures noted will be consistent with eventual measures proposed by the Joint Commission.

The actual patient flow in the program centers on someone—physician, physician extender, or nurse—identifying a patient with a fragility fracture and then entering that patient by name and number in a private log kept by each enrolled site for future reference as to treatment adherence (Fig. 3). A “case report form” actually functions as a history note form which can be completed during an interview with the patient or, in some cases, a chart review. Included in this historical review are questions pertaining to current demographics, current and previous fracture history, lifestyle risk factors, osteoporosis diagnosis and medication use, and recommendations for pharmacologic therapy and DXA scanning. That form then serves as a data source for entry of the patient into the Own the Bone registry, a web-based, de-identified repository of patient information in which each patient is entered by a number only, and that number is associated with a site-specific log as referenced above. In this scenario, each patient can be entered individually following the recording of a personal history, or a group of patients could have data submitted by a data entry specialist at a convenient time. Because the presence of an acute fracture serves as a teachable moment, each patient receives verbal and written educational information according to the measures previously described. Much of the educational material is derived from the National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF) and the National Institute of Health-Osteoporosis and Related Bone Diseases Resource Center. The NOF has joined our AOA Educational Alliance, thus affording Own the Bone the benefit of utilizing their notable, patient-friendly explanatory materials. Copies of these materials are available from the NOF for Own the Bone subscribers or, alternatively, may be downloaded and printed on site. The final essential steps in this process involve printing a letter of explanation from the registry, regarding the fracture and the need for appropriate osteoporosis treatment, for both the patient/family and the primary care physician. The patient log, kept privately at each site, allows for future follow-up in regard to treatment adherence. One of the salient features of this program involves its adaptability since each subscriber can choose to enter specific fracture types at first—such as hip and/or vertebral fractures—or enter all fragility fracture patients who satisfy the age criteria. In addition, as previously stated, while this program was originally designed for hospitalized patients, it can also be easily implemented in an emergency department facility, an outpatient fracture clinic setting subsequent to hospitalization, or for patients treated purely as outpatients.

We have mentioned subscribers, and that necessitates an explanation of the enrollment process and the benefits derived from enrolling. Following a request from the AOA for information on Own the Bone, a “champion,” or the interested party at a given facility, will be sent explanatory information in the form of an Own the Bone “Fact Sheet” and a compilation of Frequently Asked Questions. Also included are an Enrollment Form and a Participation Agreement, which must be signed by the primary investigator and a designated associate investigator, as well as by a hospital administrator. Depending on the determination at each institution, Internal Review Board (IRB) approval may be required, though, once again, this program represents a limited data set with de-identified patient information entered in the registry and may not require a stringent IRB approval. An annual participation fee of US $2,000 provides many benefits in addition to access to the registry to document physician and staff compliance with skeletal health education and treatment. “Get With The Guidelines” had a subscriber fee also. A number of implementation tools are available to participants, including webinars with on-demand registry training and best practice examples, a subscriber binder and starter guide, implementer video testimonials, branded patient education materials, and a quarterly online Bone Health Bulletin. In addition, subscribers, patients, and other medical personnel can access a wealth of information at our website www.ownthebone.org.

Despite the availability of all the elements described, one overwhelming fact remains for us and the entire bone health community. Own the Bone and improvement in bone health care both need “champions” if the message is to be heard. Champions who advocate for Own the Bone engage hospital administrators and resources in the community and encourage other champions to enroll their hospitals. The progress we have made has come about with many dedicated individuals contributing as Own the Bone evolves. From the outset, our Own the Bone Scientific Steering Committee of orthopaedic surgeons, nurses, and an advisor from internal medicine have played important roles in the program and registry design. It is noteworthy that a number of prominent orthopedists from the Orthopaedic Trauma Association have ardently supported this project because, in addition to surgery, “it is the right thing to do.”Along the way, we have been fortunate to have benefitted from significant guidance and input from a Multidisciplinary Advisory Board of various non-orthopaedic specialists who have gained national recognition through their interest and accomplishments in furthering the cause of bone health.

Now, some 18 months after official launch of Own the Bone in June, 2009, there has been significant progress. We currently have more than 85 sites enrolled, or in the process of enrolling, representing 26 states and 22 health systems. More than 1,400 patients have been entered in the registry, and physician compliance with the measures has been commendable—85% in multiple areas and more than 90% in others. Not surprisingly, hip fractures represent just over 50% of the fractures recorded. Nearly 35% of the patients reported a previous fracture, and half of those were hip fractures. That scenario is unacceptable.

So why should a hospital or clinic enroll in Own the Bone? There are four basic reasons:

-

1.

To improve patient care—it is the right thing to do.

-

2.

Positive public relations by emphasizing another area of quality, the new byword of health care goals. It should also increase patient volume when used as a marketing tool.

-

3.

Preparation for health care reform and standards from CMS, Joint Commission, and PQRI demands.

-

4.

Liability concerns and the necessity of avoiding “failure to diagnose and treat” lawsuits.

The program is not without challenges. Hospitals have myriad quality initiatives, and bone health is usually not heading that list. An economic model has to be designed to demonstrate revenue enhancements or cost savings for hospitals and clinics. That project is currently under development. Electronic medical records (EMR) use in hospitals is just evolving, and those institutions with sophisticated EMR systems and bone health programs need a simple means of linking their current program to Own the Bone. An additional hurdle is involved with indentifying the “denominator population” through the use of EMR triggers, order sets, and radiology reports that highlight less obvious problems such as silent vertebral fractures.

In summary, Own the Bone is a health care quality improvement resource that employs a systems-based approach, which encourages interaction between physicians in multiple specialties and their patients with fragility fractures, in order to improve patients' skeletal health and prevent future fractures. The systems-based methodology is a major challenge for physicians and healthcare, in general, as we enter the twenty-first century [13, 16]. The Institute of Medicine noted in 2003 that it takes nearly 17 years for evidence-based medical treatment to be incorporated into routine clinical practice. The year 2021 is far too long to wait, realizing the Surgeon General clearly stated the problem and its solution in 2004. We must decrease this adoption interval for the benefit of our patients and the healthcare system. It should now be obvious why “it's time for everyone to Own the Bone.” Simply put, it is the right time and the “right thing to do.”

References

Office of the Surgeon General, US Department of Health and Human Services (2004) Bone health and osteoporosis: a report of the Surgeon General. US Department of Health and Human Services, Washington, DC

National Osteoporosis Foundation (2002) America's bone health: the state of osteoporosis and low bone mass in our nation. National Osteoporosis Foundation, Washington, DC

LaBresh KA, Ellrodt AG, Gliklich R, Liljestrand J, Petro R (2004) Get with the guidelines for cardiovascular secondary prevention: pilot results. Arch Intern Med 164:203–209

Lee TH (2007) Eulogy for a quality measure. N Engl J Med 357:1175–1177

Solomon DH, Finkelstein JS, Katz JN, Mogun H, Avorn J (2003) Underuse of osteoporosis medications in elderly patients with fractures. Am J Med 115:398–400

American Orthopaedic Association (2005) Leadership in orthopaedics: taking a stand to own the bone. American Orthopaedic Association position paper. J Bone Joint Surg Am 87:1389–1391

Gardner MJ, Flik KR, Mooar P, Lane JM (2002) Improvement in the undertreatment of osteoporosis following hip fracture. J Bone Joint Surg Am 84:1342–1348

Harrington JT, Broy SB, Derosa AM, Licata AA, Shewmon DA (2002) Hip fracture patients are not treated for osteoporosis: a call to action. Arthritis Rheum 47:651–654

Johnell O, Kanis JA, Odén A, Sernbo I, Redlund-Johnell I, Petterson C, De Laet C, Jönsson B (2004) Fracture risk following an osteoporotic fracture. Osteoporos Int 15:175–179

Edwards BJ, Bunta AD, Feinglass J, Simonelli C, Bolander M, Fitzpatrick LA, Kaufman J (2007) Prior hip, wrist, and lower extremity fractures are common in patients with subsequent hip fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 461:226–230

National Osteoporosis Foundation (2008) Clinician's guide to prevention and treatment of osteoporosis. National Osteoporosis Foundation, Washington, DC

Tosi LL, Gliklich R, Kannan K, Koval KJ (2008) The American Orthopaedic Association's “own the bone” initiative to prevent secondary fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Am 90:163–173

Dell RM, Greene D, Anderson D, Williams K (2009) Osteoporosis disease management: what every orthopaedic surgeon should know. J Bone Joint Surg Am 91(Suppl 6):79–86

Skedros JG (2004) The orthopaedic surgeon's role in diagnosing and treating patients with osteoporotic fractures: standing discharge orders may be the solution for timely medical care. Osteoporos Int 15:405–410

Bouxsein ML, Kaufman J, Tosi LL, Cummings S, Lane J, Johnell O (2004) Recommendations for optimal care of the fragility fracture patient to reduce the risk of future fracture. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 12:385–395

Bogoch ER, Elliot-Gibson V, Beaton DE, Jamal SA, Josse RG, Murray TM (2006) Effective initiation of osteoporosis diagnosis and treatment for patients with a fragility fracture in an orthopaedic environment. J Bone Joint Surg Am 88:25–34

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the significant contributions to the evolution of Own the Bone by Novartis and the National Osteoporosis Foundation, both participating as members of the AOA/Own the Bone Educational Alliance. In addition, we recognize other significant support from Eli Lilly Corporation, the Eli Lilly Foundation, Proctor & Gamble/Sanofi-Aventis, Amgen, Synthes, and Orthovita.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bunta, A.D. It is time for everyone to own the bone. Osteoporos Int 22 (Suppl 3), 477 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1704-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00198-011-1704-0