Abstract

Objective

To compare the management of invasive candidiasis between infectious disease and critical care specialists.

Design and setting

Clinical case scenarios of invasive candidiasis were presented during interactive sessions at national specialty meetings. Participants responded to questions using an anonymous electronic voting system.

Patients and participants

Sixty-five infectious disease and 51 critical care physicians in Switzerland.

Results

Critical care specialists were more likely to ask advice from a colleague with expertise in the field of fungal infections to treat Candida glabrata (19.5% vs. 3.5%) and C. krusei (36.4% vs. 3.3%) candidemia. Most participants reported that they would change or remove a central venous catheter in the presence of candidemia, but 77.1% of critical care specialists would start concomitant antifungal treatment, compared to only 50% of infectious disease specialists. Similarly, more critical care specialists would start antifungal prophylaxis when Candida spp. are isolated from the peritonal fluid at time of surgery for peritonitis resulting from bowel perforation (22.2% vs. 7.2%). The two groups equally considered Candida spp. as pathogens in tertiary peritonitis, but critical care specialists would more frequently use amphotericin B than fluconazole, caspofungin, or voriconazole. In mechanically ventilated patients the isolation of 104 Candida spp. from a bronchoalveolar lavage was considered a colonizing organism by 94.9% of infectious disease, compared to 46.8% of critical care specialists, with a marked difference in the use of antifungal agents (5.1% vs. 51%).

Conclusions

These data highlight differences between management approaches for candidiasis in two groups of specialists, particularly in the reported use of antifungals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Invasive candidiasis is recognized as a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in critically ill non-immunocompromised patients, with crude and attributable mortality rates of more than 50% and 20%, respectively [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. Candida spp. have been identified as a significant pathogen in the European Study on the Prevalence of Nosocomial Infections in Critically Ill Patients [6]. Candidemia represents 10-20% of candidiasis cases and is the fourth leading organism responsible for nosocomial bloodstream infection in the United States, preceded by coagulase-negative staphylococci, Staphylococcus aureus, and enterococci [7, 8]. In Europe Candida spp. range among the eighth to tenth leading nosocomial bloodstream pathogens in most countries [9, 10, 11, 12]. In critically ill patients, candidemia significantly prolongs the duration of mechanical ventilation and increases workload, length of stay, and treatment costs [1, 4, 5].

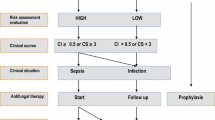

Although never verified as effective in a prospective, randomized, controlled trial in critically ill patients, early preemptive antifungal therapy may improve the prognosis of invasive candidiasis in the presence of risk factors for infection and/or significant Candida colonization [13, 14, 15]. In addition, it corresponds to current clinical practice among many experts, including Europeans [16, 17]. Colonization is the leading risk factor for infection in most series in which it has been adequately explored; Candida spp. carriage has been confirmed to be patient-specific and to precede bloodstream or invasive infections [18, 19]. While colonization may occur in a large proportion of critically ill patients, only a minority develop severe candidiasis [3, 20, 21, 22, 23]. In contrast to what is currently proposed for immunocompromised hosts [16, 24], systematic recourse to antifungal prophylaxis or preemptive therapy is not recommended for colonized critically ill patients. In the absence of large clinical series, patients susceptible to benefit from these approaches are difficult to identify, and current published recommendations are mostly derived from consensus conferences and expert opinion [25, 26, 27, 28, 29]. Accordingly, the clinical management of invasive candidiasis may differ among specialists.

The main objective of this study was to compare the management of invasive candidiasis between infectious disease and critical care specialists in Switzerland. We observed notable differences in the use of antifungals which may have important implications for the development of guidelines and postgraduate continuous education.

Material and methods

Setting

Clinical case scenarios of invasive candidiasis were presented during planned interactive sessions at the national meetings of the Swiss Society of Infectiology in March 2003 and the Swiss Society of Critical Care Medicine in May 2004. These cases included episodes of clinical sepsis related to candidemia, catheter-related candidemia, peritonitis, isolated and complicated candiduria, and clinical suspicion of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Each case is summarized in the corresponding paragraph of the results section.

Participants

Study participants included 65 infectious disease specialists and 51 critical care specialists who attended the interactive sessions. None attended both sessions. Critical care and infectious disease specialists directly involved in patient care worked in teaching hospitals (43.2% vs. 50%, respectively), university-affiliated hospitals (21.6% vs. 15.9%), community (12.7% vs. 2.3%), and private hospitals (1.6% vs. 15.9%). Among infectious disease specialists, 29.6% were also clinical microbiologists, and 13% were specialists in internal medicine. Among critical care physicians, 50% reported being board-certified in intensive care medicine, 15.9% in anesthesiology, 15.9% in internal medicine, 9.1% in pediatrics, and 2.3% in surgery. Participants worked in mixed (54.4%), medical (14.6%), surgical (12.3%), or pediatric (8.3%) intensive care units.

Methods

Participants gave their opinion by answering a series of questions using an anonymous electronic voting system. Response distribution was automatically recorded. In brief, participants were first asked to choose one of several therapeutic options for the management of patients with bloodstream infection due to Candida albicans, C. glabrata, and C. krusei. Various options for the management of the central venous access were then proposed. Participants’ opinions regarding the possible pathogenicity of Candida spp. isolated from clinical specimens were similarly recorded. The additional cases presented concerned peritonitis from bowel perforation and tertiary peritonitis, simple and complicated candiduria, and a clinical condition with suspicion of ventilator-associated pneumonia.

Statistics

To avoid a multiple testing effect in small groups, Fisher’s exact test was used to test responses with clinically relevant differences (more than 25%) between infectious disease and critical care specialists.

Results

Candidemia

-

Case presentation: A 78-year-old diabetic man presented with abdominal pain. He underwent emergency surgery for sigmoid perforation due to obstructive colon cancer. On day 5 antimicrobial therapy was broadened from amoxicillin/clavulanate to a combination of cefepime and metronidazole because of persistent low-grade fever (37.5°C). On day 9 the patient was admitted to the ICU with acute heart failure and pulmonary edema requiring noninvasive ventilation. On day 13 meropenem was empirically started for a new episode of clinical sepsis with suspicion of nosocomial pneumonia; Candida spp. grew from blood cultures.

Therapeutic options for C. albicans, C. glabrata, and C. krusei candidemia among infectious disease and critical care specialists are shown in Table 1. Two-thirds of specialists in both groups proposed to treat C. albicans candidemia using fluconazole. In contrast, fluconazole was chosen by fewer than 5% in both groups for nonalbicans Candida strains. Critical care physicians were more likely than infectious disease specialists to seek the opinion of a colleague specialized in the management of patients with fungal infections, in particular for the treatment of C. glabrata and C. krusei candidemia. Infectious disease specialists reported choosing amphotericin B or newly licensed antifungal agents (voriconazole or caspofungin) more frequently for C. krusei infection.

Catheter-associated candidemia

-

Case presentation: (The following information was added to the above-mentioned clinical scenario.) A central venous access in the left subclavian vein was used for parenteral nutrition since day 1.

The management options retained for such an episode of candidemia associated with a central venous line are shown in Table 2. Most participants reported that they would change or remove the line. As many as 77.1% of critical care specialists would start concomitant antifungals, compared to only 50% of infectious disease specialists (p<0.001).

Intra-abdominal infection

-

Case presentation: A 75-year-old patient presented with abdominal pain. Emergency surgery with surgical drainage of the peritonitis and left colon resection was performed for perforated diverticulitis. On day 3 the patient was subfebrile (37.9°C) but remained stable. Peritoneal fluid cultures obtained during surgery grew Escherichia coli and Proteus mirabilis in moderate amount (++) and C. albicans in low amount (+).

As shown in Table 3, C. albicans isolated during initial surgery for peritonitis was considered as a colonizing organism by a majority of physicians in both groups (66.6% vs. 52.7%). However, a higher proportion of critical care specialists would start antifungal prophylaxis (22.2% vs. 7.2%; p=0.04). Overall, antifungal treatment (whether considered prophylaxis or therapy) would be prescribed by more than 50% of specialists in both groups.

-

Case presentation: Ovarectomy was performed in a 65-year-old woman with adenocarcinoma. On day 4 she required revision laparatomy with resection of a perforated ileal section and end-to-end anastomosis. She received meropenem and mixed bacterial flora grew from the intraperitoneal swabs. After initial improvement, fever and clinical signs of peritonitis relapsed on day 7. Because of the lack of clinical improvement and onset of organ dysfunction, abdominal computed tomography was performed and showed diffuse peritonitis without abscess. Microbiological sampling performed at time of computed tomography recovered low amounts (+) of coagulase-negative staphylococci and Enterococcus faecium, both resistant to meropenem, and C. albicans in large amounts (+++) grew from ascitis.

The great majority of infectious disease and critical care specialists considered C. albicans as a pathogen during the course of tertiary peritonitis (Table 3). Most physicians from both groups recommended using fluconazole as a therapeutic option for C. albicans infection. However, 10.8% of critical care specialists would select amphotericin B, compared to 1.8% of infectious disease physicians only (p=0.007).

Urinary tract infection

-

Case presentation: A 75-year-old woman underwent total hip prosthesis. Intravenous line and urinary catheter were removed on day 2. She developed fever (38.5°C) on day 7 without clinical focus of infection. Routine microscopic urine examination showed 10–20 leukocytes per low power field and culture grew C. albicans (104 cfu/ml).

-

Case presentation: A 30-year-old man was admitted to the ICU for multiple trauma requiring mechanical ventilation. Initial amoxicillin/clavulanate given empirically on admission for fever of unknown origin was stopped after 3 days. On day 10, low-grade fever (38.0–38.5°C) persisted without clinical focus of infection. Blood cultures were sterile and urine culture obtained through the urinary catheter used from day 1 grew C. albicans (105 cfu/ml). Candida spp. were not isolated from any other body site.

As shown in Table 4, approx. one-third of infectious disease and critical care specialists considered Candida spp. candiduria as a true fungal infection in both simple and complicated conditions.

Respiratory tract infection

-

Case presentation: A 30-year-old man was admitted to the ICU for multiple trauma requiring mechanical ventilation. Initial amoxicillin/clavulanate given empirically for fever of unknown origin was stopped after 3 days. Fever (39.0°C) developed on day 14 with bilateral pulmonary infiltrates. Bronchoalveolar lavage was performed and grew Pseudomonas aeruginosa (102 cfu/ml), Acinetobacter baumani (102 cfu/ml), and C. albicans (104 cfu/ml). Candida spp. were not isolated from any other body site. Blood cultures remained negative.

Candida spp. counts of 104 cfu/ml recovered from a bronchoalveolar lavage performed in this patient with clinical suspicion of ventilator-associated pneumonia were considered as a colonizing organism by 94.9% of infectious disease specialists, compared to 46.8% of critical care specialists (p<0.0001; Table 5). Antifungals would have been prescribed by 5.1% of infectious disease specialists, compared to 51% of critical care specialists (p<0.001).

Table 5 Management options for clinical suspicion of ventilator-associated pneumonia

Discussion

Delay or absence of antifungal therapy is associated with poor outcome from invasive candidiasis [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]. Both intensive care and infectious disease specialists are confronted with such critical conditions. To our knowledge, this is the first report comparing the clinical management and therapeutic options for invasive candidiasis in critically ill, non-immunosuppressed patients in these two specialty groups.

Experts and consensus conferences recommend treating all episodes of candidemia with antifungals [25, 26, 27, 28, 29]. In this study, a large majority of participants from both groups of physicians reported to start antifungal therapy in patients with single blood culture-positive episodes of candidemia. Of note, a higher proportion of critical care specialists would ask colleagues for advice in cases of C. albicans, C. glabrata and C. krusei candidemia; infectious disease specialists appear to have a better knowledge of microbiological aspects. We were surprised by the low proportion of specialists choosing new antifungals for the treatment of non-albicans Candida spp. candidemia [30]. Importantly, at least 10 of 63 (15.9%) infectious disease specialists either would not treat or would seek advice from a colleague experienced in fungal infections. This may suggest that recommendations for the management of fungal infections should be promoted. In a recent prospective multicenter study in 24 adult intensive care units in Paris, France, the majority (78%) of patients with documented candidemia were treated with fluconazole, while a significant proportion (52%) received amphotericin B [31]. In our study we did not survey what would have been the nature of the initial antifungal therapy given to candidemic patients by physicians at time of awareness of blood cultures positive for Candida spp., but before knowledge of the species’ identification.

Intravenous catheters are the leading source of candidemia. To date, no randomized, controlled study has been specifically designed to assess the benefit of systematic line removal; thus management remains controversial [25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 32, 33]. Data from 15 series in which the outcome of candidemia was studied in relation to vascular access management have been reviewed elsewhere [34, 35]. They support the current recommendation to remove all vascular accesses at time of candidemia, in particular for unstable, critically ill patients [15, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 32]. A large majority of participants indicated that they would remove the central venous line in a candidemic patient, but three-quarters of critical care specialists would concomitantly start antifungals, compared to only one-half of infectious disease specialists.

Candida infections following abdominal surgery are characterized by mortality rates higher than 50% [13, 23, 36]. However, there is no consensus nor are there criteria for the diagnosis of fungal peritonitis. Some investigators consider the presence of Candida spp. in any abdominal specimen as pathogenic and recommend systematic empirical antifungal treatment, while others consider it as contamination in most situations, particularly in the case of peritonitis resulting from bowel perforation [37, 38]. There is currently no consensus about the usefulness of empirical or prophylactic antifungal therapy except in patients with pancreatitis or Candida spp. recovery from tertiary peritonitis [21, 23, 36, 37, 39]. According to our observations, although a higher proportion of critical care specialists would initiate antifungal prophylaxis when Candida spp. are isolated in the case of peritonitis from bowel perforation, more than one-half of the physicians in both groups would use antifungal treatment in such a condition. Such a difference in strategy might be explained by the different types of patient population both groups of specialists have been exposed to during their respective clinical practice.

The clinical significance of candiduria is generally unknown. It can be detected in 20–30% of critically ill patients equipped with a urinary catheter, can remain asymptomatic and disappear spontaneously, lead to pyelonephritis, or manifest occasionally as a marker of candidemia [40]. Systematic antifungal treatment of asymptomatic candiduria may not be beneficial, and experts recommend considering risk factors and underlying conditions before deciding upon eventual treatment [25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 41]. In the case of C. albicans candiduria, whether complicated or not, only one-third of participants in both groups of specialists would start antifungal therapy. More than 90% of participants in both groups indicated that they would use fluconazole for the treatment of Candida spp. candiduria. The low use of other antifungals may reflect the very low incidence of infections due to non-albicans strains of Candida in Switzerland [12]. A recent prospective multicenter study in 24 French intensive care units reported that 25% of patients treated for documented candiduria effectively received antifungal therapy, mostly fluconazole [42].

Candida spp. are often isolated from the upper respiratory tract of mechanically ventilated patients and they figure regularly among the frequent pathogens responsible for nosocomial pneumonia [43]. However, Candida spp. have a very low affinity for pneumocytes, and histologically confirmed candidal pneumonia is rare; thus the clinical significance of Candida spp. even when recovered from bronchoalveolar lavage or protected brush specimen remains difficult to determine [44, 45]. The existence of true candidal pneumonia is doubted by most investigators, who require histological demonstration of invasive disease [44, 46]. In addition, thresholds for positive quantitative cultures of bronchoalveolar lavage fluid for Candida spp. have never been evaluated and validated. Experts repeatedly recommend considering the recovery of Candida spp. from the respiratory tract as colonization that does not require antifungal therapy [25, 26, 27, 29]. Surprisingly, in our survey, in contrast to the majority of infectious disease physicians, one-half of all critical care specialists would consider the growth of high amounts of Candida spp. in a bronchoalveolar lavage as pathogenic and treat accordingly. Almost all participants of both groups indicated that they would use fluconazole for the treatment of Candida spp. ventilator-associated pneumonia.

The major limitation of our study, as in similar reports, is that it consisted of a descriptive survey of management options without validation of practices at the bedside [25, 26, 28]. Direct monitoring of physician practices would, however, be beyond the capacity of investigation. Whether reported management options correspond to practice in reality remains to be studied. The participants were nevertheless a large sample of board-certified intensive care (38%) and infectious disease (65%) specialists in Switzerland. Whether participants in the current evaluation were truly representative of all critical care and infectious disease physicians in the country, or whether participation bias could explain for the differences observed between the groups remains unknown. Furthermore, whether differences observed between Swiss specialists could be generalized to other countries deserves further investigation. Finally, this study also suggests the lack of a consistent pattern of management strategies for invasive candidiasis among specialists within the same specialty that would require further investigation. A possible future approach would be to organize a consensus conference with the two groups of specialists in an attempt to produce co-authored sets of clinical guidelines to help homogenize infection definitions and management options.

These data highlight key differences between management approaches for candidiasis among infectious disease specialists and critical care physicians. The lack of overall consensus between and among the different groups of physicians suggests that continuous educational efforts should be provided to both types of specialists.

References

Wey SB, Mori M, Pfaller MA, Woolson RF, Wenzel RP (1989) Risk factors for hospital-acquired candidemia. A matched case-control study. Arch Intern Med 149:2349–2353

Voss A, le Noble JL, Verduyn LF, Foudraine NA, Meis JF (1997) Candidemia in intensive care unit patients: risk factors for mortality. Infection 25:8–11

Nolla-Salas J, Sitges-Serra A, Leon-Gil C, Martinez-Gonzalez J, Leon-Regidor MA, Ibanez-Lucia P, Torres-Rodriguez JM (1997) Candidemia in non-neutropenic critically ill patients: analysis of prognostic factors and assessment of systemic antifungal therapy. Study Group of Fungal Infection in the ICU. Intensive Care Med 23:23–30

Blot SI, Vandewoude KH, Hoste EA, Colardyn FA (2002) Effects of nosocomial candidemia on outcomes of critically ill patients. Am J Med 113:480–485

Gudlaugsson O, Gillespie S, Lee K, Vande Berg J, Hu, J, Messer S, Herwaldt L, Pfaller M, Diekema D (2003) Attributable mortality of nosocomial candidemia revisited. Clin Infect Dis 37:1172–1177

Vincent JL, Bihari DJ, Suter PM, Bruining HA, White J, Nicolas-Chanoin MH, Wolff M, Spencer RC, Hemmer M (1995) The prevalence of nosocomial infection in intensive care units in Europe. Results of the European Prevalence of Infection in Intensive Care (EPIC) study. JAMA 274:639–644

Richards MJ, Edwards JR, Culver DH, Gaynes RP (2000) Nosocomial infections in combined medical-surgical intensive care units in the United States. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol 2:510–515

National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance (NNIS) system report (2003) Data summary from January 1992-June 2003. Am J Infect Control 31:481–498

Voss A, Kluytmans JA, Koeleman JGM et al. (1996) Occurrence of yeast bloodstream infections between 1987 and 1995 in five Dutch university hospitals. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 15:909–912

Fluit AC, Jones ME, Schmitz FJ (2000) Antimicrobial susceptibility and frequency of occurrence of clinical blood isolates in Europe from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program, 1997 and 1998. Clin Infect Dis 30:454–460

Swanden P, Bevanger L, Digranes A, Gaustad P, Haukland HH, Steinbakk M (1998) Constant low rate of fungemia in Norway, 1991 to 1996. Clin Infect Dis 36:455–459

Marchetti O, Bille J, Fluckiger U, Eggimann P, Ruef C, Garbino J, Calandra T, Glauser MP, Tauber MG, Pittet D; Fungal Infection Network of Switzerland (2004) Epidemiology of candidemia in Swiss tertiary care hospitals: secular trends 1991–2000. Clin Infect Dis 38:311–320

Solomkin JS, Flohr AB, Simmons RL (1982) Indications for therapy for fungemia in postoperative patients. Arch Surg 117:1272–1275

Rex JH, Sobel JD (2001) Prophylactic antifungal therapy in the intensive care unit. Clin Infect Dis 32:1191–1200

Eggimann P, Garbino J, Pittet D (2003) Management of Candida species infections in critically ill patients. Lancet Infect Dis 3:772–785

Hughes WT, Armstrong D, Bodey GP, Bow EJ, Brown AE, Calandra T, Feld R, Pizzo PA, Rolston KV, Shenep JL, Young LS (2002) 2002 guidelines for the use of antimicrobial agents in neutropenic patients with cancer. Clin Infect Dis 34:730–751

Gauzit R, Cohen Y, Dupont H, Hennequin C, Montravers P, Timsit JF, Veber B, Chevalier E, Blin P, Palestro B (2003) [Infections by Candida sp. in intensive care. Survey of French practices] (in French). Presse Med 32:440–449

Pittet D, Monod M, Filthuth I, Frenk E, Suter PM, Auckenthaler R (1991) Contour-clamped homogeneous electric field gel electrophoresis as a powerful epidemiologic tool in yeast infections. Am J Med 91:256S-263S

Reagan DR, Pfaller MA, Hollis RJ, Wenzel RP (1990) Characterization of the sequence of colonization and nosocomial candidemia using DNA fingerprinting and a DNA probe. J Clin Microbiol 28:2733–2738

Luzzati R, Amalfitano G, Lazzarini L, Soldani F, Bellino S, Solbiati M, Danzi MC, Vento S, Todeschini G, Vivenza C, Concia E (2000) Nosocomial candidemia in non-neutropenic patients at an Italian tertiary care center. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 19:602–607

Pittet D, Monod M, Suter PM, Frenk E, Auckenthaler R (1994) Candida colonization and subsequent infections in critically ill surgical patients. Ann Surg 220:751–758

Garbino J, Lew PD, Romand JA, Hugonnet S, Auckenthaler R, Pittet D (2002) Prevention of severe Candida infections in non-neutropenic, high-risk, critically ill patients. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in SDD-treated patients. Intensive Care Med 28:1708–1717

Eggimann P, Francioli P, Bille J, Schneider R, Wu MM, Chapuis G, Chiolero R, Pannatier A, Schilling J, Geroulanos S, Glauser MP, Calandra T (1999) Fluconazole prophylaxis prevents intra-abdominal candidiasis in high-risk surgical patients. Crit Care Med 27:1066–1072

Ascioglu S, Rex JH, De Pauw B, Bennett JE, Bille J, Crokaert F, Denning DW, Donnelly JP, Edwards JE, Erjavec Z, Fiere D, Lortholary O, Maertens J, Meis JF, Patterson TF, Ritter J, Selleslag D, Shah PM, Stenvens DA, Walsh TJ; Invasive Fungal Infections Cooperative Group of the European Organization for Research, Treatment of Cancer; Mycoses Study Group of the National Institute of Allergy, Infectious Diseases (2002) Defining opportunistic invasive fungal infections in immunocompromised patients with cancer and hematopoietic stem cell transplants: an international consensus. Clin Infect Dis 34:7–14

Edwards JE Jr, Bodey GP, Bowden RA, Buchner T, de Pauw BE, Filler SG, Ghannoum MA, Glauser M, Herbrecht R, Kauffman CA, Kohno S, Martino P, Meunier F, Mori T, Pfaller MA, Rex JH, Rogers TR, Rubin RH, Solomkin J, Viscoli C, Walsh TJ, White M (1997) International conference for the development of a consensus on the management and prevention of severe candidal infections. Clin Infect Dis 25:43–59

Vincent JL, Anaissie E, Bruining H, Demajo W, el-Ebiary M, Haber J, Hiramatsu Y, Nitenberg G, Nystrom PO, Pittet D, Rogers T, Sandven P, Sganga G, Schaller MD, Solomkin J (1998) Epidemiology, diagnosis and treatment of systemic Candida infection in surgical patients under intensive care. Intensive Care Med 24:206–216

Rex JH, Walsh TJ, Sobel JD, Filler SG, Pappas PG, Dismukes WE, Edwards JE (2000) Practice guidelines for the treatment of candidiasis. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis 30:662–678

Buchner T, Fegeler W, Bernhardt H, Brockmeyer N, Duswald KH, Herrmann M, Heuser D, Jehn U, Just-Nubling G, Karthaus M, Maschmeyer G, Muller FM, Muller J, Ritter J, Roos N, Ruhnke M, Schmalreck A, Schwarze R, Schwesinger G, Silling G; Panel of Interdisciplinary Investigators (2002) Treatment of severe Candida infections in high-risk patients in Germany: consensus formed by a panel of interdisciplinary investigators. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 21:337–352

Denning DW, Kibbler CC, Barnes RA (2003) British Society for Medical Mycology proposed standards of care for patients with invasive fungal infections. Lancet Infect Dis 3:230–240

Mora-Duarte J, Betts R, Rotstein C, Colombo AL, Thompson-Moya L, Smietana J, Lupinacci R, Sable C, Kartsonis N, Perfect J; Caspofungin Invasive Candidiasis Study Group (2002) Comparison of caspofungin and amphotericin B for invasive candidiasis. N Engl J Med 347:2020–2029

Kac G, Bougnoux ME, Aegerter P, Fagon JY, the CANDIREA Study Group (2003) Prospective multicenter surveillance study of ICU-acquired candidemia and candiduria: the candidemia analysis. In: 43rd ICAAC abstracts, American Society of Microbiology, September 2003, p 349, K-452g

British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (1994) Management of deep Candida infection in surgical and intensive care unit patients. Intensive Care Med 20:522–528

Walsh TJ, Rex JH (2002) All catheter-related candidemia is not the same: assessment of the balance between the risks and benefits of removal of vascular catheters. Clin Infect Dis 34:600–602

Nucci M, Anaissie E (2002) Should vascular catheters be removed from all patients with candidemia? An evidence-based review. Clin Infect Dis 34:591–599

Eggimann P, Garbino J, Pittet D (2003) Epidemiology of Candida species infections in critically ill non-immunosuppressed patients. Lancet Infect Dis 3:685–702

Calandra T, Bille J, Schneider R, Mosimann F, Francioli P (1989) Clinical significance of Candida isolated from peritoneum in surgical patients. Lancet II:1437–1440

Rantala A, Niinikoski J, Lehtonen OP (1993) Early Candida isolations in febrile patients after abdominal surgery. Scand J Infect Dis 25:479–485

Sandven P, Qvist H, Skovlund E, Giercksky KE (2002) Significance of Candida recovered from intraoperative specimens in patients with intra-abdominal perforations. Crit Care Med 30:541–547

Nathens AB, Rotstein OD, Marshall JC (1998) Tertiary peritonitis: clinical features of a complex nosocomial infection. World J Surg 22:158–163

Tambyah PA, Maki DG (2000) Catheter-associated urinary tract infection is rarely symptomatic: a prospective study of 1,497 catheterized patients. Arch Intern Med 160:678–682

Sobel JD (1999) Management of asymptomatic candiduria. Int J Antimicrob Agents 11:285–288

Kac G, Bougnoux ME, Aegerter P, Fagon JY, the CANDIREA Study Group (2003) Prospective multicenter surveillance study of ICU-acquired candidemia and candiduria: the candiduria analysis. In: 43rd ICAAC abstracts, American Society of Microbiology, September 2003, p 348, K-452d

Chastre J, Fagon JY (2002) Ventilator-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165:867–903

El-Ebiary M, Torres A, Fabregas N, de la Bellacasa JP, Gonzalez J, Ramirez J, del Bano D, Hernandez C, Jimenez de Anta MT (1997) Significance of the isolation of Candida species from respiratory samples in critically ill, non-neutropenic patients. An immediate postmortem histologic study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 156:583–590

Rello J, Esandi ME, Diaz E, Mariscal D, Gallego M, Valles J (1998) The role of Candida spp isolated from bronchoscopic samples in nonneutropenic patients. Chest 114:146–149

Haron E, Vartivarian S, Anaissie E, Dekmezian R, Bodey GP (1993) Primary Candida pneumonia. Experience at a large cancer center and review of the literature. Medicine (Baltimore) 72:137–142

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to the participants to the annual meetings of the Swiss Society of Infectiology and the Swiss Society of Critical Care Medicine in March 2003 (Basel) and May 2004 (Interlaken). We thank Stephan Schatt Brennan and Ralph Studer from Pfizer AG, Switzerland for supporting the organization of the interactive session. We also thank Rosemary Sudan for providing editorial assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Eggimann, P., Calandra, T., Fluckiger, U. et al. Invasive candidiasis: comparison of management choices by infectious disease and critical care specialists. Intensive Care Med 31, 1514–1521 (2005). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-005-2809-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-005-2809-8