Abstract

Aims/hypothesis

Acute or chronic exposure of beta cells to glucose, palmitic acid or pro-inflammatory cytokines will result in increased production of the p47phox component of the NADPH oxidase and subsequent production of reactive oxygen species (ROS).

Methods

Rat pancreatic islets or clonal rat BRIN BD11 beta cells were incubated in the presence of glucose, palmitic acid or pro-inflammatory cytokines for periods between 1 and 24 h. p47phox production was determined by western blotting. ROS production was determined by spectrophotometric nitroblue tetrazolium or fluorescence-based hydroethidine assays.

Results

Incubation for 24 h in 0.1 mmol/l palmitic acid or a pro-inflammatory cytokine cocktail increased p47phox protein production by 1.5-fold or by 1.75-fold, respectively, in the BRIN BD11 beta cell line. In the presence of 16.7 mmol/l glucose protein production of p47phox was increased by 1.7-fold in isolated rat islets after 1 h, while in the presence of 0.1 mmol/l palmitic acid or 5 ng/ml IL-1β it was increased by 1.4-fold or 1.8-fold, respectively. However, palmitic acid or IL-1β-dependent production was reduced after 24 h. Islet ROS production was significantly increased after incubation in elevated glucose for 1 h and was completely abolished by addition of diphenylene iodonium, an inhibitor of NADPH oxidase or by the oligonucleotide anti-p47phox. Addition of 0.1 mmol/l palmitic acid or 5 ng/ml IL-1β plus 5.6 mmol/l glucose also resulted in a significant increase in islet ROS production after 1 h, which was partially attenuated by diphenylene iodonium or the protein kinase C inhibitor GF109203X. However, ROS production was reduced after 24 h incubation.

Conclusions/interpretation

NADPH oxidase may play a key role in normal beta cell physiology, but under specific conditions may also contribute to beta cell demise.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

An increase in blood glucose concentration is the most important regulatory stimulus for pancreatic beta cell insulin secretion. In addition to glucose, other nutrients are also important regulators of insulin secretion, e.g. NEFA. Palmitate, one of the most abundant NEFA in plasma, acutely potentiates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion by beta cells, but chronically reduces it. The metabolic interaction between glucose and palmitate may generate lipid intermediates (diacylglycerol, phosphatidylserine) that activate specific isoforms of protein kinase C (PKC), thereby enhancing insulin secretion [1, 2]. Indeed, it was recently demonstrated [3] that long-chain fatty acyl-CoA, mainly palmitoyl-CoA, potentiated glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in clonal beta cells through PKC activation.

Many studies have now shown the expression and activity of phagocyte-like NADPH oxidase in non-phagocytic cells [4–6]. The NADPH oxidase consists of six hetero-subunits, which associate in a stimulus-dependent manner to form the active enzyme complex and produce superoxide. Tight regulation of enzymatic activity is achieved by two mechanisms; separation of the oxidase subunits into different subcellular locations during the resting state (cytosolic and membrane-bound), and modulation of reversible protein–protein and protein–lipid interactions. These can either promote the resting state or allow translocation to the membrane in response to appropriate stimuli. Two NADPH oxidase subunits, gp91phox and p22phox, are integral membrane proteins. They form a heterodimeric flavocytochrome b558 that forms the catalytic core of the enzyme, but exist in the inactive state in the absence of the other subunits. The additional subunits are required for regulation and are located in the cytosol during the resting state. They include the proteins p67phox, p47phox and p40phox as well as the small GTPase Rac. p47phox is phosphorylated at multiple sites by a number of protein kinases including members of the PKC family, and as such plays the most important role in the regulation of NADPH oxidase activity [7, 8].

Recently, we demonstrated the expression and activity of a phagocyte-like NADPH oxidase in pancreatic islets [9]. The expression of NADPH oxidase components was demonstrated by RT-PCR (gp91phox, p22phox and p47phox) and western blotting (p47phox and p67phox). We also found that glucose-stimulated production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) in pancreatic islets occurred by PKC-dependent activation of NADPH oxidase. This finding is similar to a report that high glucose and PKC mediated activation of NADPH oxidase and ROS production in mesangial cells [10]. Recently, it was reported [11] that glibenclamide (one of a class of clinically important insulin secretagogue drugs known as sulfonylureas) stimulated ROS production in a pancreatic beta cell line (MIN6 cells) through NADPH oxidase.

In pathological conditions leading to type 2 diabetes it is known that elevations of glucose and NEFA levels induce production of ROS in beta cells [12, 13]. It has been reported that a major source of ROS is the mitochondrion, in which increased availability of substrates causes enhanced oxidative activity and production of oxygen derivatives [12, 13]. However, we speculate that a major source of superoxide is the NADPH oxidase system, which may be upregulated in the presence of saturated NEFA, or indeed of pro-inflammatory cytokines, which are known to increase production of components of the NADPH oxidase system in the phagocytic cells of the immune system [14, 15].

Others have recently reported that nutrients (such as high levels of glucose and palmitate) stimulated cultured aortic smooth and endothelial cell phagocyte-like NADPH oxidase via PKC-dependent activation [16], while a very recent study demonstrated increased production of the NADPH oxidase components gp91phox and p22phox in beta cells obtained from animal models of type 2 diabetes [17]. However, in spite of this information, a systematic study on the effect of glucose, palmitate or pro-inflammatory cytokines (major positive or negative insulin secretion regulators) on NADPH oxidase production and activation in pancreatic beta cells has not been reported. Thus we investigated the effects of glucose, palmitate or IL-1β on the production of p47phox and activation of NADPH oxidase in isolated primary rat pancreatic islets. In addition, we used the glucose-responsive clonal rat pancreatic insulin-secreting cell line, BRIN BD11, to analyse production of p47phox after exposure to the saturated fatty acid palmitate, or a pro-inflammatory cytokine cocktail.

Materials and methods

Materials

All chemicals for buffer preparation, palmitic acid, nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT), diphenylene iodonium (DPI) and bysindoylmaleimide (GF109203X) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical (St Louis, MO, USA), or Sigma (Dublin, Ireland). Hydroethidine (HEt) was obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA). Protease inhibitors and EDTA were supplied by Pierce (Rockford, IL, USA). Culture media, fetal bovine serum, OPTI-MEM medium, oligofectamine, plasticware, trizol, random pd (N)6 primers, DNase I, SuperScript II RNase H-Reverse Transcriptase II, Taq DNA polymerase and dNTPs were obtained from Invitrogen Life Technologies (Paisley, Scotland). Cytokines were obtained from R&D Systems (Abingdon, UK). The p47phox rabbit antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). All procedures were carried out according to the various manufacturers’ instructions. Palmitic acid was initially dissolved in ethanol, the final concentration of which did not exceed 0.05%.

Animals

Female Wistar albino rats weighing 150–200 g (45–60 days old) were obtained from the Institute of Biomedical Sciences, University of Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brazil. The animals were kept in groups of five at 23°C in a room with a 12 h light–dark cycle (lights on at 07.00 hours) and free access to food and water. Ethics approval was granted for this study by the Animal Experimental Committee of the Institute of Biomedical Sciences, University of Sao Paulo.

Rat pancreatic islet isolation

Islets of Langerhans were isolated from rats by pancreas digestion with collagenase as previously described [18]. Islet apoptosis (assessed by DNA fragmentation) was not altered in any of the conditions described at any point up to 24 h.

Superoxide determination: nitroblue tetrazolium and hydroethidine assays

Total superoxide generation was detected by NBT assay [19]. Superoxide is rapidly generated on activation of NADPH oxidase and has a short half-life. However, superoxide can reduce NBT to a relatively stable product detectable at 560 nm. Previous studies have demonstrated that islet ROS-dependent NBT reduction was robust and was sustained for a 120-minute period following initiation [9]. The assay was performed by incubating 200 islets in 250 μl Krebs–Henseleit buffer, with 0.2% NBT. The samples were incubated for 60 minutes or 24 h (37°C and 5% CO2) in the presence of glucose, 0.1 mmol/l palmitate, 10 μmol/l DPI, an NADPH oxidase inhibitor [20, 21], or 500 nmol/l GF109203X, a PKC-specific inhibitor [22], or 5 ng/ml IL-1β where indicated. The cells were centrifuged (3,200 g for 2 min at 4°C) and the supernatant fraction removed. Formazan was dissolved in 100 μl 50% acetic acid by sonication (3 pulses of 6 seconds, Vibra Cell; Sonics & Materials, Newtown, CT, USA). Absorbance was determined at 560 nm in a microtitre plate reader (Spectramax Plus; Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Intracellular superoxide generation was also determined by oxidation of HEt to ethidium [23]. Islets were incubated at 37°C for 60 min or 24 h in 500 μl Krebs–Henseleit buffer in the presence of glucose (2.8, 5.6 and 16.7 mmol/l) with or without 10 μmol/l DPI, or in the presence of 5.6 mmol/l glucose plus 0.1 mmol/l palmitate, or in the presence of 5.6 mmol/l glucose plus 5 ng/ml IL-1β with or without 10 μmol/l DPI, as indicated. Islets were loaded with 100 μmol/l HEt over 20 min at room temperature. Incubation medium was replaced and the islets loaded with HEt were washed with Krebs–Henseleit buffer without glucose and transferred to 96-well plates (containing 100 μl Krebs–Henseleit buffer without glucose). Islets were visualised in a confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Morris Plains, NJ, USA). In these experiments, ethidium fluorescence was excited at 547 nm (3 μm laser scanning confocal sections were analysed).

Phosphorthioate-modified oligonucleotides

Antisense phosphorthioate oligonucleotide target to p47phox (5′-CTTCATTCGCCACATCGC-3′) and a control oligonucleotide containing the same bases but in random order (5′-TTTTCCCCCAGGCCCAAT-3′) were designed according to the p47phox mRNA rat sequence (Genbank accession no. AY029167) and were produced by Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, USA). The efficiency of antisense oligonucleotides blocking of p47phox protein production was evaluated by immunoblotting total protein extracts of isolated pancreatic islets using a specific anti-p47phox antibody.

Oligonucleotide transfection in cultured islets and superoxide determination (hydroethidine assay)

Groups of 400 freshly isolated islets were pre-incubated for 4 h at 37°C in OPTI-MEM medium plus oligofectamine with 10 mmol/l glucose and in the absence or presence of either 20 μmol/l scrambled or 20 μmol/l antisense p47phox oligonucleotide. After 4 h of transfection, 9 ml of RPMI 1640 medium with 10 mmol/l glucose and 10% fetal calf serum were added to the medium and islets were then incubated for 20 h at 37°C. Thereafter, the RPMI-1640 medium was replaced by Krebs–Henseleit containing 5.6 mmol/l glucose and the islets were incubated for 30 min. Afterwards, islets were loaded with HEt and incubated for 20 min at room temperature. The incubation medium was replaced and islets loaded with HEt were washed with Krebs–Henseleit buffer without glucose and transferred to 96-well plates. Islets were visualised using a confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss).

Western blotting for p47phox

Groups of 300 islets were incubated in Krebs–Henseleit buffer containing 5.6, 11.1 and 16.7 mmol/l glucose or 0.1 mmol/l palmitate (with 5.6 mmol/l glucose) for 60 min at 37°C. After incubation, protein from islets was extracted and diluted (1:5) in a 2-mercaptoethanol Lammeli buffer. For protein samples isolated from BRIN BD11 cells western blot analysis was carried out using 25 μg or 30 μg of cytoplasmic extracts (isolated using RIPA buffer as described below). The 25 μg or 30 μg of protein was boiled in an equal volume of 2× electrophoresis sample buffer. Equal amounts of protein were subjected to SDS-PAGE in a Bio-Rad miniature slab gel apparatus and electrophoretically transferred on to a nitrocellulose sheet, blocked in 5% BSA and incubated overnight with purified polyclonal rabbit anti-p47phox antibody. The antibodies were used at dilutions of between 1:200 and 1:10,000 (depending on cell type). The blots were washed and probed with horseradish peroxidase (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). For BRIN-BD11 cells the SuperSignal west pico chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA) was used to detect the signal. The working solution was prepared by mixing 3.5 ml of the stable peroxide solution with 3.5 ml of the luminol/enhancer solution. Glucose, palmitic acid or IL-1β at the concentrations used in this study did not alter production of a beta cell housekeeping protein glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Fig. 1) or an islet housekeeping protein, fibronectin (Figs 2, 3, 4 and 5). Islet cell viability was not altered by any of the conditions described over 24 h (results not shown).

Effect of palmitic acid or a pro-inflammatory cytokine mix on the production of the NADPH oxidase component p47phox in clonal beta cells. Western blotting analysis (a) of p47phox from protein isolated from BRIN-BD11 cells cultured for 1, 8 or 24 h in the absence (control) or presence of either 100 μmol/l palmitic acid (PA), or (b) a pro-inflammatory cytokine mix (TNF-α [1.9 ng/ml], IL-1β [2.5 ng/ml] and IFN-γ [125 ng/ml]). Western blotting was performed using rabbit anti-p47phox or anti-GAPDH polyclonal antibodies. Similar results were obtained in three to six independent experiments. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 compared with control cells cultured in the absence of fatty acid or cytokines

Effect of glucose on production of the NADPH oxidase components p47phox in rat islets. Western blotting analysis of p47phox after 1 h (a) and 24 h (b) from isolated rat pancreatic islets incubated in the presence of 5.6 (G5.6), 11.1 (G11.1) and 16.7 (G16.7) mmol/l glucose for 1 h or 24 h, respectively. Western blotting was performed using rabbit anti-p47phox or anti-fibronectin polyclonal antibodies. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, compared with 5.6 mmol/l glucose

Effect of palmitate on production of the NADPH oxidase component p47phox in rat islets. Western blotting analysis of p47phox from isolated pancreatic islets incubated in the presence of 5.6 mmol/l glucose (G5.6) or 5.6 mmol/l glucose plus 0.1 mmol/l palmitate (G5.6 + PALM) after 1 h (a) or 24 h (b). Western blotting was performed using rabbit anti-p47phox or anti-fibronectin polyclonal antibody. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, compared with 5.6 mmol/l glucose. **p < 0.01 compared with 5.6 mmol/l glucose

Effect of IL-1β on production of the NADPH oxidase components p47phox in rat islets. Western blotting analysis of p47phox from isolated pancreatic islets incubated in the presence of 5.6 mmol/l glucose (G5.6) or 5.6 mmol/l glucose plus 5 ng/ml IL-1β (G5.6 + IL-1β) after 1 h (a) or 24 h (b). Western blotting was performed using rabbit anti-p47phox or anti-fibronectin polyclonal antibody. Similar results were obtained in three independent experiments. *p < 0.05, compared with 5.6 mmol/l glucose

Effect of glucose on ROS production in isolated pancreatic islets. The production of ROS by isolated rat pancreatic islets was determined using a hydroethidine oxidation assay. The fluorescence intensity of islets was analysed using Zeiss confocal microscopy (a). Fluorescence increased as a function of glucose concentration. Groups of 20 islets were incubated in the presence of 2.8 (G2.8), 5.6 (G5.6) or 16.7 (G16.7) mmol/l of glucose and in the absence or presence of 10 μmol/l of DPI (n = 3). b As above (a) but the results are expressed as means ± SE from pools of 20 islets. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, compared with 2.8 mmol/l glucose; †p < 0.05, compared with 5.6 mmol/l glucose; ‡p < 0.05, compared with respective glucose concentration. c In addition, the islets were incubated in 10 mmol/l glucose only (C) or in the presence of a control random order oligonucleotide, ‘scrambled’ (S), or antisense (AS) p47phox, and the production of superoxide was determined as described above, after a 4-h transfection period followed by 20 h incubation. The results are expressed as means ± SE from pools of 20 islets each. ***p < 0.001, compared with the control. The p47phox or fibronectin production was also determined by western blotting (d) following transfection with control or antisense oligonucleotide and 20 h of incubation. The results are expressed as means ± SE from pools of 20 islets each. *p < 0.05, compared with the control

Culture and treatment of BRIN-BD11 cells

Clonal insulin-secreting BRIN-BD11 cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 tissue culture medium with 10% (v/v) fetal calf serum, 0.1% antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin, 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin) and 11.1 mmol/l d-glucose, pH 7.4, at 37°C in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air using an incubator (Forma Scientific Biosciences, Dublin, Ireland). For western blot analysis, the cells were seeded at 1.5 × 106 cells per well in 5 ml medium in a six-well plate. The cells were allowed to adhere overnight and then incubated as above but in the presence or absence of different concentrations of a pro-inflammatory cytokine mix (TNF-α [1.9 ng/ml], IL-1β [2.5 ng/ml] and IFN-γ [125 ng/ml]) or the presence or absence of 100 μmol/l palmitic acid for 1, 8 or 24 h. BRIN BD11 cell viability (as assessed by the tetrazolium salt WST-1, an indicator of mitochondrial integrity) was reduced by approximately 10%, in the presence of palmitic acid, but apoptosis (as assessed by loss of nuclear integrity) was increased from 5% to 25% in the presence of the pro-inflammatory cytokine cocktail after 24 h [24].

Preparation of protein extracts from BRIN-BD11 cells

BRIN-BD11 insulin-secreting cells were lysed using RIPA lysis buffer (supplied at 10× concentration; MSC, Dublin, Ireland) containing protease inhibitors. 150 μl of 1× RIPA lysis buffer was added to the cells. Cell lysates were transferred to fresh ice-cold Eppendorf tubes and were then placed on a shaker at 4°C for 15 min. The cells were then centrifuged at 14,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. The supernatant fraction was placed in a fresh tube and stored at −20°C.

Statistical analysis

Results are presented as mean ± SEM. ANOVA was employed to verify significance where appropriate, with confidence levels set at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were also performed using the unpaired Student’s t test where appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Effect of palmitate or a pro-inflammatory cytokine cocktail on BRIN‐BD11 p47phox protein production

BRIN BD11 insulin-secreting cells were incubated in the presence of 0.1 mmol/l palmitic acid or of the pro-inflammatory cytokine mix (IL-1β, TNF-α and IFN-γ) at non-toxic levels (TNF-α [1.9 ng/ml], IL-1β [2.5 ng/ml] and IFN-γ [125 ng/ml]). p47phox protein levels were subsequently determined by western blotting techniques after 1, 8 and 24 h and found to be significantly increased after incubation in the presence of palmitic acid or the pro-inflammatory cytokine cocktail after 24 h (1.5-fold and 1.75-fold, respectively) (Fig. 1a,b). Production of the housekeeping protein, GAPDH was not altered in any experimental condition.

Effect of glucose on production of rat islet p47phox

The effect of glucose on production of the NADPH oxidase component p47phox was examined in isolated rat islets by western blotting after 1 and 24 h. Incubation in the presence of 16.7 mmol/l glucose resulted in an increase in the production of p47phox by 1.7-fold after 1 h and 1.4-fold after 24 h, as compared with production at 5.6 mmol/l glucose (Fig. 2a,b). After 1 and 24 h of incubation glucose increased p47phox production in a dose-dependent manner (5.6 < 11.1 < 16.7 mmol/l glucose) (Fig. 2a,b).

Effect of palmitate or IL-1β on p47phox production

The effect of palmitate on p47phox production in rat islets was investigated by western blotting. Pancreatic islets were incubated for 1 or 24 h in the presence of 5.6 mmol/l glucose only or 5.6 mmol/l glucose plus 0.1 mmol/l palmitate. The production of p47phox in islets incubated in presence of palmitate plus glucose was increased by 1.4-fold compared with the effect of glucose only after 1 h (Fig. 3a), but was reduced by approximately 23% compared with control (5.6 mmol/l) after 24 h (Fig. 3b).

The effect of the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β on islet p47phox production was investigated by western blotting. Pancreatic islets were incubated for 1 h in the presence of 5.6 mmol/l glucose only or of 5.6 mmol/l glucose plus 5 ng/ml IL-1β. After 1 h, the production of p47phox in islets incubated in presence of IL-1β plus glucose was increased (1.8-fold) compared with the effect of glucose only (Fig. 4a); after 24 h production was reduced by approximately 21% (Fig. 4b).

Effect of glucose on ROS production in islet cells and pharmacological/molecular inhibition

Intracellular ROS production by incubated islets (as determined by HEt assay) was increased on incubation of islets in 5.6 or 16.7 mmol/l when compared with a basal concentration of 2.8 mmol/l glucose (Fig. 5a,b). DPI, an inhibitor of NADPH oxidase, completely abolished glucose induced ROS production (Fig. 5a,b).

ROS production was inhibited by a specific anti-p47phox oligonucleotide in islets cultured for 24 h in the presence of 10 mmol/l glucose (Fig. 5c). The inhibitory effect of the oligonucleotide on p47phox production was confirmed by western blotting. p47phox protein was produced at 40% of the level achieved in the absence of the oligonucleotide after 24 h (Fig. 5d), an effect not achieved with a control oligonucleotide containing the same bases but in random order.

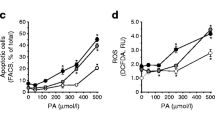

Effect of palmitate on ROS production in islet cells

Islets incubated in the presence of glucose (5.6 mmol/l) produced ROS at levels sufficient to be detected by the NBT reduction assay (which assesses both intracellular and extracellular ROS) after 1 h. Addition of 0.1 mmol/l palmitate to incubation media containing 5.6 mmol/l glucose significantly increased the NBT reduction after 1 h (1.68-fold, Fig. 6a). Additionally islets were incubated for 1 h in 5.6 mmol/l glucose plus 0.1 mmol/l palmitate in the presence of DPI, which resulted in partial attenuation of ROS production (Fig. 6a). PKC is the main cellular regulator of NADPH oxidase activity (16). The effect of GF109203X (a PKC inhibitor) was examined to ascertain the role of PKC on NADPH oxidase activation. GF109203X significantly attenuated the NBT reduction induced by palmitate plus glucose (Fig. 6b).

Effect of palmitate and NADPH oxidase or PKC inhibitors on ROS production in rat islets. The production of superoxide by isolated rat pancreatic islets incubated in glucose (G5.6) or glucose plus palmitate (PALM) in the presence or absence of 10 μmol/l DPI (a) or (b) 500 nmol/l GF109203X (GFX) was determined by NBT reduction assay. The islets were incubated for 60 min in Krebs–Henseleit buffer containing 0.2% NBT in the absence (ethanol 0.5%) or presence of 5.6 mmol/l glucose or of 5.6 mmol/l glucose plus either 0.1 mmol/l palmitate (n = 3) or DPI or palmitate plus DPI, or GF109203X or palmitate plus GF109203X. AU, arbitrary units. The results are expressed as means ± SE from pools of 100 islets each. †p < 0.05, compared with 5.6 mmol/l glucose; *p < 0.05, compared with 5.6 mmol/l glucose plus 0.1 mmol/l palmitate

Palmitate plus glucose also raised intracellular ROS production after 1 h (by 2.5-fold), as evaluated by the HEt assay, compared with 5.6 mmol/l glucose only, an effect that was partially but significantly attenuated by DPI (Fig. 7a).

Effect of palmitate or IL-1β on ROS production assessed by ethidium fluorescence in isolated pancreatic islets. The production of ROS by isolated rat pancreatic islets was determined using a hydroethidine oxidation assay. The fluorescence intensity of islets was analysed by Zeiss confocal microscopy. Groups of 20 islets were incubated for 1 h in the presence of 5.6 mmol/l glucose (G5.6), 5.6 mmol/l glucose plus 0.1 mmol/l palmitate (PALM), 5.6 mmol/l glucose plus 5 ng/ml IL-1β, and for the latter two also in the absence or presence of 10 μmol/l of DPI (a, b) (n = 3). c Islets were incubated as above (a, b), but for 24 h (n = 3). The results are expressed as means ± SE. *p < 0.05, compared with 5.6 mmol/l glucose; ***p < 0.001, as compared with 5.6 mmol/l glucose; †p < 0.05, as compared with 5.6 mmol/l glucose and 0.1 mmol/l palmitate

Effect of IL-1β on ROS production in islet cells

Islets incubated for 1 h in the presence of 5.6 mmol/l glucose plus 5 ng/ml IL-1β produced intracellular ROS at significantly higher levels compared with incubation in 5.6 mmol/l glucose only, as assessed by the hydroethidine assay. When islets were incubated for 1 h in the presence of 5.6 mmol/l glucose plus 5 ng/ml IL-1β and in the presence of DPI, a partial but significant attenuation of ROS production was observed (Fig. 7b).

Islets incubated for 24 h in the presence of palmitate or IL-1β plus glucose (5.6 mmol/l) produced intracellular ROS at significantly lower levels compared with incubation in 5.6 mmol/l glucose only, as assessed by the HEt assay. (Fig. 7c).

Discussion

We recently demonstrated the production of a phagocyte-like NADPH oxidase in the beta cells of rat pancreatic islets [9]. Expression of cytosolic and membrane NADPH oxidase components was demonstrated by RT-PCR and western blotting. Remarkably the level of ROS production in beta cells was shown to be similar although slightly lower than for rat neutrophils. We now demonstrate that p47phox, a key NADPH oxidase component, is also produced in a clonal rat pancreatic insulin-secreting cell line, BRIN BD11, that is responsive to glucose and amino acids. Thus NADPH oxidase production occurs in a pure homogenous beta cell population. Protein production of p47phox was significantly increased in the presence of palmitic acid or a pro-inflammatory cytokine cocktail after 24 h in the cell line. In rat islets, by contrast, production of p47phox protein was significantly increased in the presence of glucose, palmitic acid or the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-1β after 1 h, but was reduced after 24 h in the presence of the latter two agents. We have reported here that, similarly to leucocytes, vascular cells and mesangial cells, glucose stimulated ROS production in islets mainly through NADPH oxidase activation (based on DPI and antisense oligonucleotide results). Indeed ROS production may be positively correlated with glucose-stimulated insulin secretion [25], although previously the source of beta cell ROS had been a matter of speculation. Recently it was reported [11] that glucose and sulfonylureas stimulated ROS production in a beta cell line, MIN6, through activation of NADPH oxidase. Pro-inflammatory cytokines are known to increase NADPH oxidase production and activity in the phagocytic cells of the immune system such as neutrophils and monocytes [14, 15]. It is thus intriguing that components of the NADPH oxidase system are expressed in the pancreatic beta cell. From the evidence provided in this paper and others [9–11], it can be deduced that glucose rapidly increases production and activity of the NADPH oxidase system in the beta cell. It is possible that enhanced production of NADPH oxidase is more robust in vivo, where both glucose and palmitic acid concentrations may remain chronically elevated, and this may lead to elevated levels of apoptosis. Of related interest, arachidonic acid, which promoted insulin secretion and proliferation in the BRIN BD11 insulin-secreting cell line [26], did not increase p47phox production up to 24 h after exposure (results not shown).

IL-1β is known to induce apoptosis of islet cells by stimulating cytochrome c release from the mitochondria with subsequent activation of downstream caspases [27]. Pro-inflammatory cytokine mixtures (especially IL-1β, TNF-α and IFN-γ) are often required to induce death in rat beta cell lines, and appear to activate key caspases resulting in DNA fragmentation and induction of apoptosis. Cytokines also induce nitric oxide synthase production in beta cells, but nitric oxide production is not absolutely required for cytokine-induced beta cell death [26]. We have reported in this paper that IL-1β mediated an up-regulation of p47phox production and ROS production in islet cells, while a pro-inflammatory cytokine cocktail increased p47phox protein levels in the clonal beta cell line BRIN BD11. It is therefore possible that pro-inflammatory cytokines increase NADPH-oxidase-dependent ROS production in the beta cell, resulting in Jun N-terminal kinase activation, cytochrome c release, caspase activation and thus apoptosis as recently described [28].

Reduction of p47phox production in rat islets after 24 h of exposure to sub-apoptotic levels of IL-1β may reflect activation of a cellular protective mechanism which in vivo would reduce levels of apoptosis. Indeed most beta cell lines are generally more resistant to apoptosis than their primary cell counterpart, and so enhanced p47phox production may be tolerated at 24 h in the BRIN BD11 cell line, as reported here. However, exposure to pro-inflammatory cytokines at higher levels will induce apoptosis by increasing nitric oxide synthesis and activating stress response pathways (including endoplasmic reticulum stress) and mitochondrial dysfunction.

The NADPH oxidase complex will use NADPH as a source of reducing equivalents and molecular oxygen to generate O2 −. The source of the NADPH is of critical importance to the beta cell, which has a relatively low pentose phosphate pathway activity [27]. Interestingly the beta cell contains malic enzyme, capable of converting malate to pyruvate with the concomitant production of NADPH from NADP+ [29]. The function of the generation of NADPH in the beta cell, although positively correlated with insulin secretion, has never been clarified. We would suggest that NADPH contributes to ROS generation via its role as substrate in the NADPH-oxidase-catalysed reduction of molecular oxygen. While the normal role of ROS in the beta cell must at present be a matter of speculation, it may be related to the regulation of redox-sensitive enzymes, signal transduction components or transcription factors, which can subsequently regulate secretion and insulin gene transcription. However, in conditions that are damaging and pathogenic to beta cells, such as the continuously high circulating levels of both glucose and palmitic acid known to occur in type 2 diabetes [30, 31] or the sustained exposure to pro-inflammatory cytokines known to occur in type 1 diabetes, the upregulated production and activity of NADPH oxidase may result in excessive ROS production in the beta cell. This would subsequently impact on mitochondrial function, resulting in impaired ATP production and insulin secretion, and possibly contributing to an increase in apoptosis [32]. However, in vitro a prolonged period of incubation may result in a reduction in extracellular palmitic acid or cytokine levels (due to consumption or proteolysis, respectively), thus lowering the primary stimulus. In vivo, where fatty acid or cytokine levels can remain high over extended periods, beta cell ROS generation and its regulation in the context of mitochondrial dysfunction, endoplasmic reticulum stress and other apoptotic mechanisms may be a unifying biochemical mechanism that contributes to beta cell dysfunction and destruction in either type 1 or type 2 diabetes.

We also present evidence here that the glucose-dependent effect of palmitate on ROS production by islets is mediated via PKC activation, probably involving diacylglycerol production and subsequent stimulation of PKC activity (a mechanism reported for glucose-induced ROS production in mesangial cells [10]). Therefore glucose and palmitate together may augment de novo synthesis of diacylglycerol (palmitate rich), PKC activation and consequently NADPH oxidase activation in pancreatic islet cells. As PKC is involved in the amplifying (KATP channel-independent) mechanism controlling insulin secretion, the effect of palmitic acid would not be expected to involve alteration of ion-channel-dependent events that control insulin secretion.

ROS generation and its regulation may thus be used by a wide variety of cell types for different physiological purposes. Phagocytic cells may use ROS generation for bacterial damage and destruction, but protect themselves due to high levels of expression and activities of anti-oxidant enzyme systems including superoxide dismutase and catalase. Pancreatic beta cells may be particularly susceptible to ROS damage due to low levels of production of specific antioxidant enzymes including catalase [33, 34]. Beta cells may therefore be particularly susceptible to excessive ROS generation in the presence of additional stress, e.g. nitric oxide and mitochondrial dysfunction, therefore explaining their unique response to palmitic acid and pro-inflammatory cytokines resulting in dysfunction and destruction in either type 2 or type 1 diabetes.

Abbreviations

- DPI:

-

diphenylene iodonium

- GAPDH:

-

glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase

- GF109203X:

-

bysindoylmaleimide

- HEt:

-

hydroethidine

- NBT:

-

nitroblue tetrazolium

- PKC:

-

protein kinase C

- ROS:

-

reactive oxygen species

References

Alcazar O, Qiu-yue Z, Gine E, Tamarit-Rodriguez J (1997) Stimulation of islet protein kinase C translocation by palmitate requires metabolism of the fatty acid. Diabetes 46:1153–1158

Haber EP, Procópio J, Carvalho CRO, Carpinelli AR, Newsholme P, Curi R (2006) New insights into fatty acid modulation of pancreatic beta cell function. Int Rev Cytol 248:1–41

Yaney GC, Korchak HM, Corkey BE (2000) Long-chain acyl CoA regulation of protein kinase C and fatty acid potentiation of glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in clonal beta-cells. Endocrinology 141:1989–1998

Quinn MT, Ammons MCB, DeLeo FR (2006) The expanding role of NADPH oxidases in health and disease: no longer just agents of death and destruction. Clin Sci 111:1–20

Sheppard FR, Kelher MR, Moore EE, McLaughlin NJ, Banerjee A, Silliman CC (2005) Structural organization of the neutrophil NADPH oxidase: phosphorylation and translocation during priming and activation. J Leukoc Biol 78:1025–1042

Dupuy C, Virion A, Ohayon R, Kaniewski J, Deme D, Pommier J (1991) Mechanism of hydrogen peroxide formation catalyzed by NADPH oxidase in thyroid plasma membrane. J Biol Chem 266:3739–3743

Bey EA, Xu B, Bhattacharjee A et al (2004) Protein kinase C delta is required for p47phox phosphorylation and translocation in activated human monocytes. J Immunol 173:5730–5738

Fontayne A, Dang PM, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, El-Benna J (2002) Phosphorylation of p47phox sites by PKC alpha, beta II, delta, and zeta: effect on binding to p22phox and on NADPH oxidase activation. Biochemistry 41:7743–7750

Oliveira HR, Verlengia R, Carvalho CR, Britto LR, Curi R, Carpinelli AR (2003) Pancreatic beta-cells express phagocyte-like NADPH oxidase. Diabetes 52:1457–1463

Hua H, Munk S, Goldberg H, Fantus G, Whiteside CI (2003) High glucose-suppressed endothelin-1 Ca2+ signaling via NADPH oxidase and diacylglycerol-sensitive protein kinase C isozymes in mesangial cells. J Biol Chem 278:33951–33962

Tsubouchi H, Inoguchi T, Inuo M et al (2005) Sulfonylurea as well as elevated glucose levels stimulate reactive oxygen species production in the pancreatic beta-cell line, MIN6—a role of NADPH oxidase in beta-cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 326:60–65

Carlsson C, Borg LA, Welsh N (1999) Sodium palmitate induces partial uncoupling and reactive oxygen species in rat pancreatic islets in vitro. Endocrinology 140:3422–3428

Brownlee M (2001) Biochemistry and molecular biology of diabetic complications. Nature 414:813–820

Brown GE, Stewart MQ, Bissonnette SA, Elia AE, Wilker E, Yaffe MB (2004) Distinct ligand-dependent roles for p38 MAPK in priming and activation of the neutrophil NADPH oxidase. J Biol Chem 279:27059–27068

Mazzi P, Donini M, Margotto D, Wientjes F, Dusi S (2004) IFN-gamma induces gp91phox expression in human monocytes via protein kinase C-dependent phosphorylation of PU.1. J Immunol 172:4941–4947

Inoguchi T, Li P, Umeda F et al (2000) High glucose level and free fatty acid stimulate reactive oxygen species production through protein kinase C-dependent activation of NAD(P)H oxidase in cultured vascular cells. Diabetes 49:1939–1945

Nakayama M, Inoguchi T, Sonta T et al (2005) Increased expression of NAD(P)H oxidase in islets of animal models of type 2 diabetes and its improvement by an AT1 receptor antagonist. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 332:927–933

Lacy PE, Kostianovsky M (1967) Method for the isolation of intact islets of Langerhans from the rat pancreas. Diabetes 16:35–39

Schrenzel J, Serrander L, Banfi B et al (1998) Electron currents generated by the human phagocyte NADPH oxidase. Nature 392:734–737

el-Benna J, Park JW, Ruedi JM, Babior BM (1995) Cell-free activation of the respiratory burst oxidase by protein kinase C. Blood Cells Mol Dis 21:201–206

Cross AR, Jones OT (1986) The effect of the inhibitor diphenylene iodonium on the superoxide-generating system of neutrophils. Specific labelling of a component polypeptide of the oxidase. Biochem J 237:111–116

Suzuki Y, Ono Y, Hirabayashi Y (1998) Rapid and specific reactive oxygen species generation via NADPH oxidase activation during Fas-mediated apoptosis. FEBS Lett 425:209–212

Bindokas VP, Kuznetsov A, Sreenan S, Polonsky KS, Roe MW, Philipson LH (2003) Visualizing superoxide production in normal and diabetic rat islets of Langerhans. J Biol Chem 278:9796–9801

Cunningham G, McClenaghan NH, Flatt PR, Newsholme P (2005) l-Alanine induces changes in metabolic and signal transduction gene expression in a clonal pancreatic beta cell line and protects from pro-inflammatory cytokine induced apoptosis. Clin Sci 109:447–455

Fridlyand LE, Philipson LH (2004) Does the glucose-dependent insulin secretion mechanism itself cause oxidative stress in pancreatic beta-cells? Diabetes 53:1942–1948

Dixon G, Nolan J, McClenaghan NH, Flatt PR, Newsholme P (2004) Arachidonic acid, palmitic acid and glucose are important for the modulation of clonal pancreatic beta cell insulin secretion, growth and functional integrity. Clin Sci 106:191–199

Papaccio G, Graziano A, Valiante S, D’Aquino R, Travali S, Nicoletti F (2005) Interleukin (IL)-1beta toxicity to islet beta cells: efaroxan exerts a complete protection. J Cell Physiol 203:94–102

Kamata H, Honda S, Maeda S, Chang L, Hirata H, Karin M (2005) Reactive oxygen species promote TNFalpha-induced death and sustained JNK activation by inhibiting MAP kinase phosphatases. Cell 120:649–661

MacDonald MJ (1995) Feasibility of a mitochondrial pyruvate malate shuttle in pancreatic islets. Further implication of cytosolic NADPH in insulin secretion. J Biol Chem 270:20051–20058

Shimabukuro M, Zhou YT, Levi M, Unger RH (1998) Fatty acid-induced beta cell apoptosis: a link between obesity and diabetes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 95:2498–2502

El Assaad W, Buteau J, Peyot M-L et al (2003) Saturated fatty acids synergise with elevated glucose to cause pancreatic beta-cell death. Endocrinology 144:4154–4163

Brownlee M (2003) A radical explanation for glucose induced pancreatic beta-cell dysfunction. J Clin Invest 112:1788–1790

Gurgul E, Lortz S, Tiedge M, Jorns A, Lenzen S (2004) Mitochondrial catalase overexpression protects insulin-producing cells against toxicity of reactive oxygen species and proinflammatory cytokines. Diabetes 53:2271–2280

Lortz S, Tiedge M, Nachtwey T, Karlsen AE, Nerup J, Lenzen S (2000) Protection of insulin-producing RINm5F cells against cytokine-mediated toxicity through overexpression of antioxidant enzymes. Diabetes 49:1123–1130

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by The State of São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), Programme for Support for Centres of Excellence (PRONEX, Brazil), The National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, Brazil), The Health Research Board of Ireland and Enterprise Ireland. We are grateful to A. da Silva Alves for the excellent technical assistance with the confocal microscope.

Duality of interest

There is no duality of interest with regard to any of the authors of this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional information

D. Morgan and H. R. Oliveira-Emilio contributed equally to this study.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Morgan, D., Oliveira-Emilio, H.R., Keane, D. et al. Glucose, palmitate and pro-inflammatory cytokines modulate production and activity of a phagocyte-like NADPH oxidase in rat pancreatic islets and a clonal beta cell line. Diabetologia 50, 359–369 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-006-0462-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-006-0462-6