Abstract

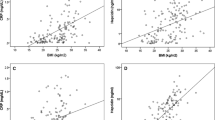

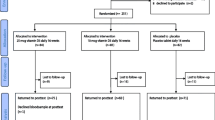

Specific recommendations for anemic individuals consist in increasing red meat intake, but the population at large is advised to reduce consumption of red meat and increase that of fish, in order to prevent the risk of developing cardiovascular disease. This study aimed to determine the effects of consuming an oily fish compared to a red meat diet on iron status in women with low iron stores. The study was designed attending the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) statement guidelines. It was a randomised crossover dietary intervention study of two 8-week periods. Twenty-five young women with low iron stores completed the study. Two diets containing a total of 8 portions of fish, meat and poultry per week were designed differing only in their oily fish or red meat content (5 portions per week). At the beginning and the end of each period blood samples were taken and hemoglobin, hematocrit, serum ferritin, serum iron, serum transferrin, serum transferrin receptor-2 and the Zn-protoporphyrin/free-protoporphyrin ratio were determined. Food intake and body weight were monitored. During the oily fish diet, PUFA intake was significantly higher (p=0.010) and iron intake lower (mean±SD, 11.5±3.4 mg/dayvs. 13.9±0.1 mg/day, p=0.008), both diets providing lower mean daily iron intake than recommended for menstruating women. Although there were no significant differences after 16 weeks, serum ferritin moderately decreased and soluble transferrin receptor increased with the oily fish, while changes with the red meat diet were the opposite. In conclusion, an oily fish diet compared to a red meat diet does not decrease iron status after 8 weeks in iron deficient women.

Resumen

Las recomendaciones nutricionales dirigidas a personas con anemia consisten generalmente en aumentar el consumo de carne roja, mientras que las recomendaciones para la población general están enfocadas a la reducción del consumo de esta carne y aumentar el consumo de pescado, con el fin de reducir el riesgo de desarrollar enfermedades cardiovasculares. El presente estudio se diseñó para investigar los efectos del consumo de una dieta basada en pescado azul frente a una de carne roja sobre el estado de hierro de mujeres con bajas reservas de hierro. Este estudio se planteó de acuerdo con la guía CONSORT (patrones consolidados para la publicación de ensayos). Se trató de una intervención nutricional cruzada, aleatorizada, con 2 periodos de 8 semanas cada uno. Veinticinco mujeres finalizaron el estudio. Se diseñaron dos dietas que contenían 8 raciones de pescado, carne y aves a la semana. Sólo se diferenciaban en el contenido de pescado azul o carne roja (4 raciones semanales). Al inicio y final de cada periodo se obtuvieron muestras de sangre y se analizó la concentración de hemoglobina, hematocrito, ferritina, hierro sérico, transferrina, receptor-2 de la transferrina y el cociente Zn-protoporfirina/ protoporfirina libre. El peso y la ingesta de alimentos se controlaron durante el estudio. Durante la dieta de pescado azul la ingesta de ácidos grasos poliinsturados (AGP) fue significativamente mayor (p=0,010) y la ingesta de hierro se redujo (media±SD, 11,5±3,4 frente a 13,9±0,1 mg/día, p=0.008), siendo el aporte de hierro menor al recomendado para esta población. Aunque no se encontraron diferencias significativas durante 16 semanas, la ferritina descendió ligeramente y la concentración del receptor de transferrina aumentó con la dieta de pescado azul, mientras que los cambios observados con la dieta rica en carne roja fueron los opuestos. En conclusión, una dieta basada en pescado azul comparada con una dieta rica en carne roja, no provoca un descenso en el estado de hierro de mujeres con deficiencia de hierro después de 8 semanas.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Aranceta J., Serra-Majem L.L. (2001). Estructura general de las guías alimentarias para la población española. Decálogo para una dieta saludable. In: Sociedad Española de Nutrición Comunitaria, ed. Guías alimentarias para la población española. Madrid: IM&C. pp. 183–94.

Baech S.B., Hansen M., Bukhave K.,et al. (2003). Nonheme iron absorption from a phytate-rich meal is increased by the addition of small amounts of pork meat.Am J Clin Nutr,77, 173–79.

Ball M.J., Bartlett M.A. (1999). Dietary intake and iron status of australian vegetarian women.Am J Clin Nutr,70, 353–58.

British Nutrition Foundation (1992). Unsaturated fatty acids: nutritional and physiological significance: the report of the British Nutrition Foundation’s Task Force. London: Chapman & Hall.

Cook J.D., Dassenko S.A., Lynch S.R. (1991). Assesment of the role of nonheme-iron availability in iron balance.Am J Clin Nutr,54, 717–22.

Craig W.J. (1994). Iron status of vegetarians.Am J Clin Nutr,59, 1233S-7S.

Department of Health and Human Service, US Food and Drug Administration. Substances affirmed as generally recognized as safe: menhaden oil. Federal register, June 5, 1997. Vol 62, No. 108:30751–757. Available at: http://frwebgate. access.gpo.gov/cgi-bin/getdoc.cgi?dbname= 1997_register&docid=fr05jn97-5. Last Access: May, 2007.

Engelmann M.D., Davidsson L., Sandstrom B., Walczyk T., Hurrell R.F., Michaelsen K.F. (1998). The influence of meat on nonheme iron absorption in infants.Pediatr Res,43, 768–73.

Fairweather-Tait S.J. (2004). Iron nutrition in the UK: getting the balance right.Proc Nutr Soc,63, 519–28.

Haddad E.H., Berk L.S., Kettering J.D., Hubbard R.W., Peters W.R. (1999). Dietary intake and biochemical, hematologic, and inmune status of vegans compared with nonvegetarians.Am J Clin Nutr,70, 586S-93S.

Hallberg L., Bjorn-Rasmussen E., Garby L., Pleehachinda R., Suwanik R. (1978). Iron absorption from South-East diets and the effects of iron fortification.Am J Clin Nutr,31, 1403–8.

Hallberg L., Hulthen L. (2000). Prediction of dietary iron absorption: an algorithm for calculating absorption and bioavailability of dietary iron.Am J Clin Nutr,71, 1147–1160.

Huh E.C., Hotchkiss A., Brouillette J., Glahn R.P. (2004). Carbohydrate fractions from cooked fish promote iron uptake by Caco-2 cells.J Nutr,134, 1681–1689.

Hunt J.R. (2003). High-, but not low-bioavailability diets enable substancial control of women’s iron absorption in relation to body iron stores, with minimal adaptation within several weeks.Am J Clin Nutr,78, 1168–1177.

Hunt J.R., Roughead Z.K. (1999). Nonhemeiron absorption, fecal ferritin excretion, and blood indexes of iron status in women consuming controlled lactoovovegetarian diets for 8 wk.Am J Clin Nutr,69, 944–952.

Hunt J.R., Roughead Z.K. (2000). Adaptation of iron absorption in men consuming diets with high or low iron bioavailability.Am J Clin Nutr,71, 94–102.

Hurrell R.F., Lynch S.R., Trinidad T.P., Dassenko SA, Cook J.D. (1998). Iron absorption in humans bovine serum albumin compared to beef muscle and egg white.Am J Clin Nutr,47, 102–7.

Hurrell R.F., Reddy M.B., Juillerat M., Cook J.D. (2006). Meat protein fractions enhance nonheme iron absorption in humans.J Nutr,136, 2808–12.

Instituto Nacional de Estadística, Spanish Government. http://www.ine.es/inebmenu/indice. htm Last acces: May, 2007.

Metzgeroth G., Adelberger V., Dorn-Beineke A.,et al. (2005). Soluble transferrin receptor and zinc protoporphyrin — competitors or efficient partners?Eur J Haematol,75, 309–317.

Navas-Carretero S, Pérez-Granados A.M., Sarriá B., Carbajal A., Pedrosa M.M., Roe M.A., Fairweather-Tait S.J. and Vaquero M.P. (2008). Oily fish increases iron bioavailability of a phytate rich meal in young iron deficient women.J Am Coll Nutr,27, 96–101.

Navas-Carretero S., Pérez Granados A.M., Schoppen S, Vaquero MP (2009). An oily fish diet increases insulin sensitivity compared to a red meat diet in young iron-deficient women.Br J Nutr. In press. Published online by Cambridge University Press 12th February 2009 (First view articles).

NRC (National Research Council). Recommended Dietary Allowances. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 1989.

Pérez-Granados A.M., Vaquero M.P., Navarro MP (1995). Iron metabolism in rats consuming oil from fresh or fried sardines.Analyst,120, 899–903.

Reddy M.B., Hurrell R.F., Cook J.D. (2000). Estimation of nonheme-iron bioavailability from meal composition.Am J Clin Nutr,71, 937–943.

Reddy M.B., Hurrell R.F., Cook J.D. (2006). Meat consumption in a varied diet marginally influences nonheme iron absorption in normal individuals.J Nutr,136, 576–581.

Sarria B, Navas-Carretero S, López-Parra A.M., Pérez-Granados A.M., Arroyo-Pardo E., Roe M.A., Teucher B., Vaquero M.P., Fairweather-Tait S.J. (2007). The G277S transferrin mutation does not affect iron absorption in iron deficient women.Eur J Nutr,46, 57–60.

Snetselaar L., Stumbo P., Chenard C., Ahrens L, Smith K., Zimmerman B. (2004). Adolescents eating diets rich in either lean beef or lean poultry and fish reduced fat and saturated fat intake and those eating beef maintained serum ferritin status.J Am Diet Assoc,104, 424–428.

Tetens I., Bendsten K.M., Henriksen M., Ersboll A.K., Milman N. (2007). The impact of a meatversus a vegetable-based diet on iron status in women of childbearing age with small iron stores.Eur J Nutr,46, 439–445.

Vaquero M.P., Veldhuizen M., Sarriá B. (2001). Consumption of an infant formula supplemented with long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids and iron metabolism in rats.Inn Food Sci Em Technol,2, 211–217.

WHO (1992). The prevalence of anaemia in women: a tabulation of available information. Geneva, World Health Organization. Document WHO/NUT/MCM/92.2.

WHO/NHD (2001). Iron deficiency anaemia: assessment, prevention and control. A guide for programme managers. Geneva, World Health Organization (document WHO/NHD/01.3).

WHO (2009) http://www.who.int/nutrition/ topics/ida/en/index.html Last access: 8th January 2009.

Zimmermann M.B., Hurrell R.F. (2007). Nutritional iron deficiency.Lancet,370, 511–520

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Navas-Carretero, S., Pérez-Granados, A.M., Schoppen, S. et al. Iron status biomarkers in iron deficient women consuming oily fish versus red meat diet. J Physiol Biochem 65, 165–174 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03179067

Received:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03179067