Abstract

Microgravity imposes adaptive changes in the human body. This review focuses on the changes in baroreflex function produced by actual spaceflight, or by experimental models that simulate microgravity, e.g., bed rest. We will analyze separately studies involving baroreflexes arising from carotid sinus and aortic arch afferents (“high-pressure baroreceptors”), and cardiopulmonary afferents (“low-pressure receptors”). Studies from unrelated laboratories using different techniques have concluded that actual or simulated exposure to microgravity reduces baroreflex function arising from carotid sinus afferents (“carotic-cardiac baroreflex”). The techniques used to study the carotid-cardiac baroreflex, using neck suction and compression to simulate changes in blood pressure, have been extensively validated. In contrast, it is more difficult to selectively study aortic arch or cardiopulmonary baroreceptors. Nonetheless, studies that have examined these baroreceptors suggest that microgravity produces the opposite effect, ie, an increase in the gain of aortic arch and cardiopulmonary baroreflexes. Furthermore, most studies have focus on instantaneous changes in heart rate, which almost exclusively examines the vagal limb of the baroreflex. In comparison, there is limited information about the effect of microgravity on sympathetic function. A substantial proportion of subjects exposed to microgravity develop transient orthostatic intolerance. It has been proposed that alterations in baroreflex function play a role in the orthostatic intolerance induced by microgravity. The evidence in favor and against this hypothesis is reviewed.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Smith RF, Stanton K, Stoop D, et al. Quantitative electrocardiography during extended space flight.Acta 1973; 2:89–102.

Fritsch-Yelle JM, Charles JB, Jones MM, et al. Microgravity decreases heart rate and arterial pressure in humans.J Appl Physiol 1996; 80(3):910–914.

Convertino VA. Physiological adaptations to weightlessness: effects on exercise and work performance.Exerc Sport Sci Rev 1990; 18:119–166.

Ertl A (for the Autonomic Neurolab Team investigators). Sympathetic responses to orthostatic stress in space.Circulation 1998; 98:1–471 (abstract).

Buckey Jr. JC, Lane LD, Levine BD, et al. Orthostatic intolerance after spaceflight.J Appl Physiol 1996; 81(1):7–18.

Watenpaugh DE, Hargens AR. The cardiovascular system in microgravity. In:Handbook of physiology. Fregly MJ, Blatteis CM, eds. New York: Oxford University Press; 1995. pp. 631–674.

Robertson D, Jacob G, Ertl A, et al. Clinical models of cardiovascular regulation after weightlessness.Med Sci Sports Exerc 1996; 96(Suppl 10):S80-S84.

Biaggioni I. Orthostatic intolerance syndrome: vasoregulatory asthenia and other hyperadrenergic states. In:Disorders of the autonomic nervous system. Robertson D, Biaggioni I, eds. London: Harwood Academic Publishers; 1994. pp. 271–285.

Schondorf R, Low PA. Idiopathic postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS): an attenuated form of acute pandysautonomia?.Neurology 1993; 43:132–137.

Jacob G, Biaggioni I. Idiopathic orthostatic intolerance and postural tachycardia syndromes.Am J Med Sci 1999; 317(2):88–101.

Blomqvist CG, Stone HL. Cardiovascular adjustments to gravitational stress. In:Handbook of physiology. Shepherd JT, Abboud FM, eds. Bethesda, MD: American Physiological Society; 1983. pp. 968–1025.

Spyer KM. Neural organization and control of the baroreceptor reflex.Rev Physiol Biochem Pharmacol 1981; 88:24–124.

Nathan MA, Reis DJ. Chronic labile hypertension produced by lesions of the nucleus tractus solitarii in the cat.Circ Res 1977; 40:72–81.

Biaggioni I, Whetsell WO, Jobe J, et al. Baroreflex failure in a patient with central nervous system lesions involving the nucleus tractus solitarii.Hypotension 1994; 94(4):491–495.

Robertson D, Hollister AS, Biaggioni I, et al. The diagnosis and treatment of baroreflex failure.N Engl J Med 1993; 329: 1449–1455.

Ross CA, Ruggiero DA, Park DH, et al. Tonic vasomotor control by the rostral ventrolateral medulla: Effect of electrical or chemical stimulation of the area containing C1 adrenaline neurons on arterial pressure, heart rate, and plasma catecholamines and vasopressin.J Neurosci 1984; 4:474–494.

Fritsch JM, Rea RF, Eckberg DL. Carotid baroreflex resetting during drug-induced arterial pressure changes in humans.Am J Physiol 1989; 256:549–553.

Sprenkle JM, Eckberg DL, Goble RG, et al. Device for the rapid quantification of human carotid baroreceptor-cardiac reflex responses.J Appl Physiol 1986; 60:727–732.

Kent BB, Drane JW, Blumenstein B, et al. A mathematical model to assess changes in the baroreceptor reflex.Cardiology 1972; 57(5):295–310.

Eckberg DL, Convertino VA, Fritsch JM, et al. Reproducibility of human vagal carotid baroreceptor-cardiac reflex responses.Am J Physiol 1992; 92(pt 2):R215-R220.

O'Leary DS. Heart rate control during exercise by baroreceptors and skeletal muscle afferents.Med Sci Sports Exerc 1996; 28:210–217.

Fritsch JM, Eckberg DL. Effects of weightlessness on human baroreflex function.Aviat Space Environ Med 1992; 63:439 (abstract).

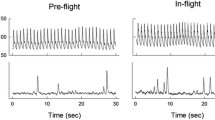

Fritsch JM, Charles JB, Bennett BS, et al. Short-duration spaceflight impairs human carotid baroreceptor-cardiac reflex responses.J Appl Physiol 1992; 73(2):664–671.

Fritsch-Yelle JM, Charles JB, Jones MM, et al. Spaceflight alters autonomic regulation of arterial pressure in humans.J Appl Physiol 1994; 94(4):1776–1783.

Convertino VA, Doerr DF, Eckberg DL, et al. Head-down bed rest impairs vagal baroreflex responses and provokes orthostatic hypotension.J Appl Physiol 1990; 68:1458–1464.

Thompson CA, Tatro DL, Ludwig DA, et al. Baroreflex responses to acute changes in blood volume in humans.Am J Physiol 1990; 259(pt 2):R792-R798.

Engelke KA, Doerr DF, Convertino VA. A single bout of exhaustive exercise affects integrated baroreflex function after 16 days of head-down tilt.Am J Physiol 1995; 95(pt 2):R614-R620.

Hughson RL, Maillet A, Gharib C, et al. Reduced spontaneous baroreflex response slope during lower body negative pressure after 28 days of head-down bed rest.J Appl Physiol 1994; 77(1): 69–77.

Crandall CG, Engelke KA, Pawelczyk JA, et al. Power spectral and time based analysis of heart rate variability following 15 days head-down bed rest.Aviat Space Environ Med 1994; 94(12): 1105–1109.

Crandall CG, Engelke KA, Convertino VA, et al. Aortic baroreflex control of heart rate after 15 days of simulated microgravity exposure.J Appl Physiol 1994; 77(5):2134–2139.

Bishop VS, Malliani A, Thoren P. Cardiac mechanoreceptors. In:Handbook of physiology: the cardiovascular system. Shepherd JT, Abboud FM, eds. Bethesda MD: American Physiological Society; 1983. pp. 497–555.

Convertino VA, Baumgartner N. Effects of hypovolemia on aortic baroreflex control of heart rate in humans.Aviat Space Environ Med 1997; 68(9 Pt 1):838–843.

Convertino VA, Doerr DF, Ludwig DA, et al. Effect of simulated microgravity on cardiopulmonary baroreflex control of forearm vascular resistance.Am J Physiol 1994; 94(pt 2):R1962-R1969.

Taylor JA, Halliwill JR, Brown TE, et al. ‘Non-hypotensive’ hypovolaemia reduces ascending aortic dimensions in humans.J Physiol 1995; 95(pt 1):289–298.

Convertino VA, Polet JL, Engelke KA, et al. Evidence of increased β-adrenoreceptor responsiveness induced by 14 days of simulated microgravity in humans.Am J Physiol 1997; 273:R93-R99.

Pawelczyk JA, Levine BD. Limb vascular responsiveness to adrenergic agonists following physical deconditioning.Med Sci Sports Exerc 1996; 27(suppl 5):S31 (abstract).

Eckberg DL, Rea RF, Andersson OK, et al. Baroreflex modulation of sympathetic activity and sympathetic neurotransmitters in humans.Acta Physiol Scand 1988; 133:211–231.

Greenleaf JE, Wade CE, Leftheriotis G. Orthostatic responses following 30-day bed rest deconditioning with isotonic and isokinetic exercise training.Aviat Space Environ Med 1989; 60:537–542.

Greenleaf JE, Bernauer EM, Ertl AC, et al. Work capacity during 30 days of bed rest with isotonic and isokinetic exercise training.J Appl Physiol 1989; 67:1820–1826.

Fritsch-Yelle JM, Whitson PA, Bondar RL, et al. Subnormal norepinephrine release relates to presyncope in astronauts after spaceflight.J Appl Physiol 1996; 81(5):2134–2141.

Mosqueda-Garcia R, Furlan R, Fermandez-Violante R, et al. Sympathetic and baroreceptor reflex function in neurally mediated syncope evoked by tilt.J Clin Invest 1997; 99(11):2736–2744.

Morillo CA, Eckberg DL, Ellenbogen KA, et al. Vagal and sympathetic mechanisms in patients with orthostatic vasovagal syncope.Circulation 1997; 96(8):2509–2513.

Aksamit TR, Floras JS, Victor RG, et al. Paroxysmal hypertension due to sinoaortic baroreceptor denervation in humans.Hypotension 1987; 9:309–314.

Yamada Y, Miyajima E, Tochikubo O, et al. Impaired baroreflex changes in muscle sympathetic nerve activity in adolescents who have a family history of essential hypertension.J Hypertens 1988; 6(4):S525-S528.

Ditto B, France C. Carotid baroreflex sensitivity at rest and during psychological stress in offspring of hypertensives and non-twin sibling pairs.Psychosom Med 1990; 52(6):610–620.

Convertino VA, Fritsch JM. Attenuation of human carotid-cardiac vagal baroreflex responses after physical detraining.Aviat Space Environ Med 1992; 92(9):785–788.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ertl, A.C., Diedrich, A. & Biaggioni, I. Baroreflex dysfunction induced by microgravity: potential relevance to postflight orthostatic intolerance. Clinical Autonomic Research 10, 269–277 (2000). https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02281109

Received:

Accepted:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02281109