Abstract

Background: Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic neurologic disease associated with gait impairment that adversely affects quality of life (QOL). Data are lacking on the impact of these impairments from the perspectives of people with MS and care partners of a person with MS, defined as individuals caring for a friend or family member with MS.

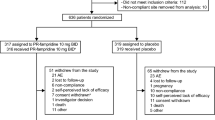

Methods: In January and February 2008, online surveys were conducted by Harris Interactive® (HI) on behalf of Acorda Therapeutics, Inc. and the National MS Society (USA) to explore the impact of difficulty walking (defined as trouble walking at least twice a week and/or an inability to walk at least twice a week due to MS) from the perspectives of people with MS and care partners of a person with MS. The study population was drawn from pre-existing panels, generated by HI and eRewards market research, of self-reported people with MS, care partners of a person with MS, or adults living in the same household as a person with MS. Panel members were invited to participate by e-mail, and their status/eligibility was verified with screening questions. Survey results were weighted for demographic factors and propensity to be online. Percentages were adjusted to account for acceptance of multiple responses and exclusion of non-responses.

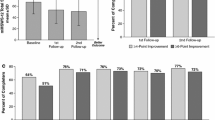

Results: The respondents included 1011 people with MS and 317 care partners. Demographic and MS disease characteristics in the people with MS sample were similar to those of people with MS in the general population. Among people with MS, 41% reported having difficulty walking, including 13% with inability to walk at least twice a week. Of those with difficulty walking, 70% said it was the most challenging aspect of having MS. Of those with inability to walk at least twice a week, 74% said it disrupted their daily lives. Only 34% of people with MS with difficulty walking were employed. Communication between people with MS and physicians regarding difficulty walking was suboptimal; 39% of all people with MS said they never or rarely discussed it with their doctor. Significant percentages of all care partners experienced reduced QOL and socioeconomic status in association with caring for a person with MS.

Conclusions: Difficulty walking is a common impairment in people with MS, with adverse effects on the QOL of people with MS and care partners of a person with MS.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Frohman EM. Multiple sclerosis. Med Clin N Am 2003; 87: 867–97

National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Epidemiolog of MS [online]. Available from URL: http://www.nationalmsso ciety.org/about-multiple-sclerosis/what-we-know-about-ms/who-gets-ms/epidemiology-of-ms/index.aspx [Accessed 2010 Nov 1]

Wu N, Minden SL, Hoaglin DC, et al. Qualit of life in people with multiple sclerosis: data from the Sonya Slifka Longitudinal Multiple Sclerosis Study. J Health Hum Serv Adm 2007; 30: 233–67

Ebers GC, Heigenhauser L, Daumer M, et al. Disabilit as an outcome in MS clinical trials. Neurology 2008; 71: 624–31

Weinshenker BG, Bass B, Rice GP, et al. The natural histor of multiple sclerosis: a geographicall based study. I: clinical course and disability. Brain 1989; 112: 133–46

Kelleher KJ, Spence W, Solomonidis S, et al. Ambulator rehabilitation in multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil 2009; 31: 1625–32

Pearson OR, Busse ME, Van Deursen RW, et al. Quantification of walking mobilit in neurological disorders. QJM 2004; 97: 463–75

Myhr KM, Riise T, Vedeler C, et al. Disabilit and prognosis in multiple sclerosis: demographic and clinical variables important for the abilit to walk and awarding of disabilit pension. Mult Scler 2001; 7: 59–65

Tremlett H, Paty D, Devonshire V. Disabilit progression in multiple sclerosis is slower than previousl reported. Neurology 2006; 66: 172–7

Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disabilit status scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983; 33: 1444–52

Rudick RA, Cutter G, Reingold S. The Multiple Sclerosis Functional Composite: a new clinical outcome measure for multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2002; 8: 359–65

Amato MP, Portaccio E. Clinical outcome measures in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 2007; 259: 118–22

WHO/International Classification of Functioning: walking [online]. Available from URL: http://a s.who.int/classi fications/icfbrowser/ [Accessed 2010 Nov 1]

Hemmett L, Holmes J, Barnes M, et al. What drives qualit of life in multiple sclerosis? QJM 2004; 97: 671–6

Jones CA, Pohar SL, Warren S, et al. The burden of multiple sclerosis: a communit health survey. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2008; 6: 1–7

Heesen C, Böhm J, Reich C, et al. Patient perception of bodil functions in multiple sclerosis: gait and visual function are the most valuable. Mult Scler 2008; 14: 988–91

Datamonitor Healthcare Reports. Treatment algorithms 1999: segmenting the multiple sclerosis patient population. London: Datamonitor, 1999

Prescott JD, Factor S, Pill M, et al. Descriptive analysis of the direct medical costs of multiple sclerosis in 2004 using administrative claims in a large nationwide database. J Manag Care Pharm 2007; 13: 44–52

Salter A, Vollmer T, Marrie RA, et al. Socioeconomic impact of earl mobilit impairment in patients with multiple sclerosis: results from the NARCOMS Registr [abstract]. Neurology 2009; 72: A80

Salter A, Cutter GR, Tyry T, et al. Impact of loss of mobilit on instrumental activities of dail living and socioeconomic status in patients with MS. Curr Med Res Opin 2010; 26: 493–500

Finlayson M, vanDenend T. Experiencing the loss of mobility: perspectives of older adults with MS. Disabil Rehabil 2003; 25: 1168–80

Harris Interactive® [online]. Available from URL: http://www.harrisinteractive.com/about/ [Accessed 2010 Oct 28]

Freeman JA. Improving mobilit and functional independence in persons with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2001; 248: 255–9

Lord SE, Halligan PW, Wade DT. Visual gait analysis: the development of a clinical assessment and scale. Clin Rehabil 1998; 12: 107–19

Holden MK, Gill KM, Magliozzi MR. Gait assessment for neurologicall impaired patients: standards for outcome assessment. Phys Ther 1986; 66: 1530–9

Rodgers MM, Mulcare JA, King DL, et al. Gait characteristics of individuals with multiple sclerosis before and after a 6-month aerobic training program. J Rehabil Res Dev 1999; 36: 183–8

Gehlsen G, Beckman K, Assmann N, et al. Gait characteristics in multiple sclerosis: progressive change and effects of exercise on parameters. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 1986; 67: 536–9

Lord SE, McPherson K, McNaughton HK, et al. Communit ambulation after stroke: how important and obtainable is it and what measures a ear predictive? Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004; 85: 234–9

Gabriele W, Renate S. Work loss following stroke. Disabil Rehabil 2009; 31: 1487–93

Rigby H, Gubitz G, Eskes G, et al. Caring for stroke survivors: baseline and 1-year determinants of caregiver burden. Int J Stroke 2009; 4: 152–8

Vincent C, Desrosiers J, Landreville P, et al., BRAD group. Burden of caregivers of people with stroke: evolution and predictors. Cerebrovasc Dis 2009; 27: 456–64

Noseworthy JH, Lucchinetti C, Rodriguez M, et al. Multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2000; 343: 938–52

Rodriguez M, Siva A, Ward J, et al. Impairment, disability, and handicap in multiple sclerosis: a population-based stud in Olmsted County, Minnesota. Neurology 1994; 44: 28–33

McDonnell GV, Hawkins SA. An assessment of the spectrum of disabilit and handicap in multiple sclerosis: a population-based study. Mult Scler 2001; 7: 111–7

Edgley K, Sullivan M, Dehoux E. A surve of multiple sclerosis: determinants of employment. Can J Rehabil 1991; 4: 127–32

Julian LJ, Vella L, Vollmer T, et al. Employment in multiple sclerosis: exiting and re-entering the work force. J Neurol 2008; 255: 1354–60

Vickray BG, Hays RD, Harooni R, et al. A health-related qualit of life measure for multiple sclerosis. Qual Life Res 1995; 4: 187–206

Solari A, Radice D. Health status of people with multiple sclerosis: a communit mail survey. Neurol Sci 2001; 22: 307–15

Riazi A, Hobart JC, Lamping DL, et al. Using the SF-36 measure to compare the health impact of multiple sclerosis and Parkinson's disease with normal population health profiles. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2003; 74(6): 710–4

Nortvedt MW, Riise T, Myhr KM, et al. Qualit of life in multiple sclerosis: measuring the disease effects more broadly. Neurology 1999; 53: 1098–103

Paltamaa J, Sarasoja T, Leskinen E, et al. Measures of physical functioning predict self-reported performance in self-care, mobility, and domestic life in ambulator persons with multiple sclerosis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2007; 88: 1649–57

Iezzoni LI. When walking fails. JAMA 1996; 276: 1609–13

Rietberg MB, Brooks D, Uitdehaag BM, et al. Exercise therap for multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005 Jan 25; (1): CD003980

Dalgas U, Stenager E, Ingemann-Hansen T. Review: multiple sclerosis and physical exercise: recommendations for the a lication of resistance-, endurance- and combined training. Mult Scler 2008; 14: 35–53

Wiles CM. Physiotherap and related activities in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler 2008; 14: 863–71

Motl RW, Snook EM, Schapiro RT. Symptoms and physical activit behavior in individuals with multiple sclerosis. Res Nurs Health 2008; 31: 466–75

Stroud N, Minahan C, Sabapathy S. The perceived benefits and barriers to exercise participation in persons with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil 2009; 31(26): 2216–22

Calkins DR, Rubenstein LV, Cleary PD, et al. Failures of physicians to recognize functional disabilit in ambulator patients. Ann Intern Med 1991; 114: 451–4

McKeown LP, Porter-Armstrong AP, Baxter GD. The needs and experiences of caregivers of individuals with multiple sclerosis: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil 2003; 17: 234–48

Aronson KJ. Qualit of life among persons with multiple sclerosis and their caregivers. Neurology 1997; 48: 74–80

Chipchase SY, Lincoln NB. Factors associated with carer strain in carers of people with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil 2001; 23: 768–76

Knight RG, Devereux RC, Godfrey HP. Psychosocial consequences of caring for a spouse with multiple sclerosis. J Clin Exp Psych Neuropsychol 1997; 19: 7–19

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted online by HI on behalf of Acorda Therapeutics and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (USA). The author wishes to thank Celesta Cheo of HI for her contribution in conducting the surveys and for reviewing the data and approving the final version of this manuscript. This project was supported by Acorda Therapeutics, Inc. (Hawthorne, NY, USA) and the National Multiple Sclerosis Society (USA). Nicholas LaRocca received editorial support from The Curry Rockefeller Group, LLC. (Tarrytown, NY, USA). Nicholas LaRocca, PhD, is an employee of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. The author has no other relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript apart from those disclosed. Preparation of this manuscript was financed by Acorda Therapeutics, Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

LaRocca, N.G. Impact of Walking Impairment in Multiple Sclerosis. Patient-Patient-Centered-Outcome-Res 4, 189–201 (2011). https://doi.org/10.2165/11591150-000000000-00000

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.2165/11591150-000000000-00000