Abstract

Purpose

The objective of this study was to determine the glycemic index (GI) and glycemic load (GL) of three products from the Brazilian market used as a supplement and food formula for oral and/or enteral nutrition.

Methods

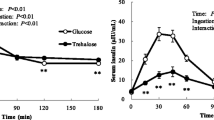

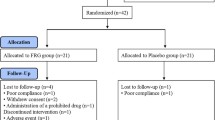

The volunteers (n = 16) attended Food Research Center weekly for six weeks after a 10–12-h overnight fasting. Blood was sampled in the fasting state (t = 0) and at 15 min, 30 min, 45 min, 60 min, 90 min, and 120 min after starting to eat each evaluated meal: glucose solution (reference food, three times) and three products: Cubitan® vanilla (specific for wounds healing), Diasip® chocolate, and Diasip® vanilla (diabetic supplements). GI was determined by calculating the area under the glycemic response curve using the trapezoidal rule and ignoring the areas below the fasting line and considering the GI of glucose to be 100. To determine GL, it was considered the amount of carbohydrates available in a standard serving of the product and GI.

Results

The three products studied showed low GI and low GL (Cubitan® GI = 35, GL = 6; Diasip® chocolate GI = 49, GL = 7; Diasip® vanilla GI = 47, GL = 7), with significant differences from those and the reference food, but no significant difference between them. Similar results were also observed for the blood glucose peak, which occurred 30 min after the consumption of all products.

Conclusions

GI and GL of the products were considerably lower than those of the reference food. The products evaluated presented a low glycemic response, shown by a glycemic response curve with a slightly accentuated shape and no high peaks.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data availability

Datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request and with authorization from the sponsor company.

Abbreviations

- GI :

-

Glycemic index

- GL :

-

Glycemic load

- AUC :

-

Area under the curve

References

Jenkins DJ, Wolever TM, Taylor RH, et al. Glycemic index of foods: a physiological basis for carbohydrate exchange. Am J Clin Nutr. 1981;34:362–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/34.3.362.

Wolever TM. Dietary carbohydrates and insulin action in humans. Br J Nutr. 2000;83(Suppl 1):S97-102. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0007114500001021.

Barclay AW, Petocz P, McMillan-Price J, et al. Glycemic index, glycemic load, and chronic disease risk – a meta-analysis of observational studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87:627–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/87.3.627.

Brouns F, Bjorck I, Frayn KN, et al. Glycaemic index methodology. Nutr Res Rev. 2005;18:145–71. https://doi.org/10.1079/NRR2005100.

Augustin LS, Franceschi S, Jenkins DJA, et al. Glycemic index in chronic disease: a review. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56:1049–71. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601454.

Brand-Miller JC. Glycemic load and chronic disease. Nutr Rev. 2003;61:S49-55. https://doi.org/10.1301/nr.2003.may.S49-S55.

Ludwig DS. Glycemic load comes of age. J Nutr. 2003;133:2695–6. https://doi.org/10.1093/jn/133.9.2695.

Venn BJ, Green TJ. Glycemic index and glycemic load: measurement issues and their effect on diet-disease relationships. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;61(Suppl 1):S122-131. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602942.

Zhang J-Y, Jiang Y-T, Liu Y-S, et al. The association between glycemic index, glycemic load, and metabolic syndrome: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of observational studies. Eur J Nutr. 2020;59:451–63. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00394-019-02124-z.

Chiavaroli L, Lee D, Ahmed A, et al. Effect of low glycaemic index or load dietary patterns on glycaemic control and cardiometabolic risk factors in diabetes: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2021;374:n1651. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n1651.

World Health Organization. Global Diabetes Summit (who.int). 2021. https://www.who.int/newsroom/events/detail/2021/04/14/default-calendar/global-diabetes-summit. Accessed 1 May 2022.

Cañedo-Dorantes L, Cañedo-Ayala M. Skin acute wound healing: a comprehensive review. Int J Inflamm. 2019;2019:e3706315. https://doi.org/10.1155/2019/3706315.

Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes. Diretrizes da Sociedade Brasileira de Diabetes 2019-2020. 2020. http://www.saude.ba.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Diretrizes-Sociedade-Brasileira-de-Diabetes-2019-2020.pdf. Accessed 5 Oct 2022.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2019 abridged for primary care providers. Clin Diabetes. 2019;37:11–34. https://doi.org/10.2337/cd18-0105.

Matos LBN, Piovacari SMF, Ferrer R et al. Diretrizes of Brazilian Society of Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition - BRASPEN - Campanha Diga Não à Lesão por Pressão. 2020. https://www.famap.com.br/wpcontent/uploads/2020/09/campanhadiganaoalesaoporpressao.pdf. Accessed 7 Oct 2022.

National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel. Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries: Clinical Practice Guideline. 2019. https://www.internationalguideline.com/. Accessed 7 Oct 2022.

Munoz N, Posthauer ME. Nutrition strategies for pressure injury management: Implementing the 2019 International Clinical Practice Guideline. Nutr Clin Pract. 2022;37:567–82. https://doi.org/10.1002/ncp.10762.

National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel, European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and Pan Pacific Pressure Injury Alliance. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: Quick reference guide. Emily Haesler (ed) EPUAP/NPIAP/PPPIA, Cambridge Media. 2019. https://www.internationalguideline.com/static/pdfs/Quick_Reference_Guide-10Mar2019.pdf. Accessed 7 Oct 2022.

Raghav A, Khan ZA, Labala RK, et al. Financial burden of diabetic foot ulcers to world: a progressive topic to discuss always. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab. 2018;9:29–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/2042018817744513.

Cereda E, Klersy C, Serioli M, et al. A nutritional formula enriched with arginine, zinc, and antioxidants for the healing of pressure ulcers: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2015;162:167–74. https://doi.org/10.7326/M14-0696.

Cereda E, Gini A, Pedrolli C, Vanotti A. Disease-specific, versus standard, nutritional support for the treatment of pressure ulcers in institutionalized older adults: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:1395–402. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02351.x.

Sociedade Brasileira de Nutrição Parenteral e Enteral, Associação Brasileira de Nutrologia e Sociedade Brasileira de Clínica Médica. Terapia Nutricional para Portadores de Úlceras por Pressão. 2011. https://amb.org.br/files/_BibliotecaAntiga/terapia_nutricional_para_pacientes_portadores_de_ulceras_por_pressao.pdf. Accessed 3 Jun 2022.

McCleary B, McNally M, Rossiter P, et al. Measurement of resistant starch by enzymatic digestion in starch and selected plant materials: collaborative study. J AOAC Int. 2002;85:1103–11. https://doi.org/10.1093/jaoac/85.5.1103.

Bergmeyer HU, Bernet E. Determination of glucose with oxidase and peroxidase. In: Bergmeyer HU (ed) Methods of enzymatic analysis, 2nd edn. Academic Press, New York; 1974;1205–1215

International Organization for Standardization ISO 26642. Food products - Determination of the glycaemic index (GI) and recommendation for food classification First edition. 2010. https://wholecane.com/wpcontent/uploads/2019/08/Glucose-ISO_266422010E-Character_PDF_document-copy.pdf. Accessed 20 Aug 2020.

Food and Agriculture Organization/ World Health Organization. Carbohydrates in human nutrition: report of a joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation, Food and Nutrition Paper, 66. Rome: FAO; p. 140.

Foster-Powell K, Holt SHA, Brand-Miller JC. International table of glycemic index and glycemic load values: 2002. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76:5–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/76.1.5.

Glycemic Index Foundation. Low GI Explained. 2022. https://www.gisymbol.com/low-gi-explained/. Accessed 3 Jun 2022.

Ministério da Saúde. Agência Nacional de Vigilância Sanitária RDC 359/2003 - Aprova Regulamento Técnico de porções de alimentos embalados para fins de rotulagem nutricional. 2003. https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/saudelegis/anvisa/2003/rdc0359_23_12_2003.html. Accessed 8 Jun 2022

Danone SA. Internal company data. Reports from internal studies conducted by the Danone SA in Singapore (2020), South Africa (2012), London (2008 and 2006). 2022.

Ojo O, Weldon SM, Thompson T, et al. The effect of diabetes-specific enteral nutrition formula on cardiometabolic parameters in patients with type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta–analysis of randomised controlled trials. Nutrients. 2019;11:1905. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11081905.

Kokubo E, Morita S, Nagashima H, et al. Blood glucose response of a low-carbohydrate oral nutritional supplement with isomaltulose and soluble dietary fiber in individuals with prediabetes: a randomized, single-blind crossover trial. Nutrients. 2022;14(12):2386. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu14122386.

Vlachos D, Malisova S, Lindberg FA, et al. Glycemic index (GI) or glycemic load (GL) and dietary interventions for optimizing postprandial hyperglycemia in patients with T2 diabetes: a review. Nutrients. 2020;12:1561. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12061561.

Lansink M, van Laere KMJ, Vendrig L, Rutten GEHM. Lower postprandial glucose responses at baseline and after 4 weeks use of a diabetes-specific formula in diabetes type 2 patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;93:421–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2011.05.019.

Magnoni D, Rouws CHFC, Lansink M, et al. Long-term use of a diabetes-specific oral nutritional supplement results in a low-postprandial glucose response in diabetes patients. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2008;80:75–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2007.10.027.

Ohiagu F, Chikezie P, Chikezie C. Pathophysiology of diabetes mellitus complications: metabolic events and control. Biomed Res Ther. 2021;8:4243–57. https://doi.org/10.15419/bmrat.v8i3.663.

Zubair M, Ahmad J. Role of growth factors and cytokines in diabetic foot ulcer healing: a detailed review. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2019;20:207–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11154-019-09492-1.

Cereda E, Klersy C, Andreola M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a disease-specific oral nutritional support for pressure ulcer healing. Clin Nutr. 2017;36:246–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2015.11.012.

Heyman H, Van De Looverbosch DEJ, Meijer EP, et al. Benefits of an oral nutritional supplement on pressure ulcer healing in long-term care residents. J Wound Care. 2008;17(11):476–480. https://doi.org/10.12968/jowc.2008.17.11.31475.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the volunteers who participated in the clinical trial and contributed with their time and goodwill.

Funding

Danone Brazil Ltda.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

E.B.G. conceived and designed the study and participated in the data collection and analysis of the results. E.B.G., J.A.A.V., G.A.R., M.V.R., C.L.M.A., and M.C.R. participated in the drafting of the article and the critical review. All authors reviewed the manuscript and agreed to its final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Approval CEP/FCF 2.814.784 was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

G.A.R., C.L.M.A., M.C.R., J.A.A.V., and M.V.R. are employees of Danone Brazil Ltda. G.A.R and C.L.M.A. work in the Evidence Generation Department, and M.C.R., J.A.A.V., and M.V.R. work in the Medical Affairs Department. EBG (Researcher at FoRC) declares that there is no conflict of interest with the products used in this research.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Giuntini, E.B., Ruffo, G.A., de Abreu, C.L.M. et al. Glycemic response of volunteers to the consumption of supplements and food formulas for oral and/or enteral nutrition. Nutrire 47, 32 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41110-022-00182-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s41110-022-00182-8