Abstract

Background

The high transmission and fatality rates of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) strain intensive care resources and affect the treatment and prognosis of critically ill patients without COVID-19. Therefore, this study evaluated the differences in characteristics, clinical course, and prognosis of critically ill medical patients without COVID-19 before and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

This retrospective cohort study included patients from three university-affiliated tertiary hospitals. Demographic data and data on the severity, clinical course, and prognosis of medical patients without COVID-19 admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) via the emergency room (ER) before (from January 1 to May 31, 2019) and during (from January 1 to May 31, 2021) the COVID-19 pandemic were obtained from electronic medical records. Propensity score matching was performed to compare hospital mortality between patients before and during the pandemic.

Results

This study enrolled 1161 patients (619 before and 542 during the pandemic). During the COVID-19 pandemic, the Simplified Acute Physiology Score (SAPS) 3 and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) scores, assessed upon ER and ICU admission, were significantly higher than those before the pandemic (p < 0.05). The lengths of stay in the ER, ICU, and hospital were also longer (p < 0.05). Finally, the hospital mortality rates were higher during the pandemic than before (215 [39.7%] vs. 176 [28.4%], p < 0.001). However, in the propensity score-matched patients, hospital mortality did not differ between the groups (p = 0.138). The COVID-19 pandemic did not increase the risk of hospital mortality (odds ratio [OR] 1.405, 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.937–2.107, p = 0.100). SAPS 3, SOFA score, and do-not-resuscitate orders increased the risk of in-hospital mortality in the multivariate logistic regression model.

Conclusions

In propensity score-matched patients with similarly severe conditions, hospital mortality before and during the COVID-19 pandemic did not differ significantly. However, hospital mortality was higher during the COVID-19 pandemic in unmatched patients in more severe conditions. These findings imply collateral damage to non-COVID-19 patients due to shortages in medical resources during the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, strategic management of medical resources is required to avoid these consequences.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is characterized by a hyperacute outbreak and high fatality due to respiratory failure [1, 2]. A substantial number of patients require admission to the intensive care unit (ICU) and mechanical ventilation [3,4,5,6], which causes a crisis in the health care system [7, 8]. Therefore, a shortage of medical resources during the COVID-19 pandemic has directly affected non-COVID-19 patients by delaying and disrupting appropriate treatment [9, 10]. In particular, critically ill non-COVID-19 patients have experienced fatal consequences, even under the relatively well-controlled severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) transmission conditions in Korea [11].

Since the first surge of COVID-19 in Daegu, the Korean healthcare system has been adapted to reduce the chance of exposure of non-COVID-19 patients to SARS-CoV-2 [12]. In hospitals, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for SARS-CoV-2 is performed for patients with fever or respiratory symptoms at the emergency department (ED) and later, for all patients awaiting admission. COVID-19 patients are isolated from non-COVID-19 patients in the ED, general ward, and intensive care unit (ICU). To maintain this system, the Korean government has provided a substantial number of ICU beds for COVID-19 patients who need critical care in tertiary hospitals. However, these changes have caused a burden on the medical system for non-COVID-19 patients, and access to tertiary hospitals for non-COVID-19 patients has become increasingly difficult.

Higher severity and poor prognosis could be expected even in non-COVID-19 patients, given the burden on the medical system during this time. However, this effect has not been evaluated in countries with relatively effective control of the COVID-19 outbreak. Therefore, this study evaluated collateral damage to the critical care system during the COVID-19 pandemic in Korea. We compared the differences in patient characteristics, clinical course, and prognosis before and during the COVID-19 pandemic, and analyzed factors expected to influence the mortality of critically ill non-COVID-19 patients.

Methods

Study design

This was a multicenter retrospective cohort study. We screened and enrolled medical patients admitted to the ICU via the ED in three university-affiliated tertiary hospitals with 800–1200 beds in Seoul and the capital region, which accounted for > 60% of the daily COVID-19 incidence during the study period. These hospitals comprised 48–65 ICU beds, of which medical patients occupied 25–35 beds before the pandemic. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused the change of several systems in the emergency room (ER) and ICU of these hospitals, as well as patient characteristics, clinical course, and prognosis. We evaluated these changes due to the COVID-19 pandemic and analyzed the factors related to mortality in propensity score-matched patients.

Study population

This study enrolled patients with critical medical conditions who were admitted to the ICU via the ER between January 1 and May 31, 2019, and between January 1 and May 31, 2021—after the government’s official order for increased ICU capacity for COVID-19 patients. Patients with surgical conditions or neurological issues, as well as those admitted to the ICU from the general ward, were excluded. Patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection were excluded from the study. Although ICUs are described as surgical, medical, cardiac, emergency, or neurocritical care units, they are run by an open system in which the boundary of each unit is dynamic. Therefore, eligible patients from any division of internal medicine were recruited during the study period.

Data collection

Patient data were acquired from electronic medical records. We evaluated demographic parameters, medical history, comorbidities, severity scores calculated at ER and ICU admission (Simplified Acute Physiology Score [SAPS] 3 and Sequential Organ Failure Assessment [SOFA] score), and lengths of stay in the ER, ICU, and hospital. Organ support—including mechanical ventilation, continuous renal replacement therapy, and extracorporeal membrane oxygenation—and the presence of a do-not-resuscitate (DNR) order were investigated.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables are reported as numbers and frequencies (%). Continuous variables are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) and median (interquartile range [IQR]). Differences in frequencies were compared using the chi-squared test. Differences in continuous variables were compared using the t test, Mann–Whitney test, and analysis of variance. Hospital mortality was compared between propensity score-matched patients. Considering the possibility of a non-linear relationship between age and mortality, we divided the patient group by 70 years using Youden’s index in the logistic regression analysis. Included in the multivariate logistic regression model were the groups from before and during the COVID-19 pandemic period and factors related to hospital mortality from the univariate logistic regression analysis, including age > 70 years, Charlson comorbidity score, SAPS 3, SOFA score at ICU admission, and cause of ICU admission. In propensity score analysis, 1084 patients were included; patients with missing values were excluded in this analysis. Propensity score was calculated using logistic regression considering patient characteristics of age, Charlson comorbidity index, cause of admission, length of ER stay, presence of a DNR order, and SAPS3. Then, in each block for men and women after exact matching for sex, 1:1 propensity score matching was performed with the nearest neighbor matching method without replacement. The caliper width for the matching was 0.25 of the standard deviation of the logit of the propensity score. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics (version 20.0; IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and R 4.1.2 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) for windows.

Results

Baseline patient characteristics

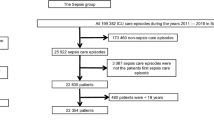

This study enrolled a total of 1161 patients, including 619 patients who were admitted to the ICU between January 1 and May 31, 2019, and 542 who were admitted to the ICU between January 1 and May 31, 2021 (Fig. 1a). The mean patient age was 68.1 ± 15.7 years, and 739 (63.7%) patients were men. These patients had at least one comorbidity, with a mean Charlson comorbidity score of 4.2 ± 1.9. The severity of the patients’ conditions, as evaluated in the ER using the SAPS 3 and SOFA scores, was 69.1 ± 19.7 and 7.6 ± 4.2, respectively. The most common cause of admission was respiratory disease except for COVID-19 (367, 31.6%), followed by sepsis (238, 20.5%) and cardiovascular disease (212, 18.3%) (Table 1).

Comparisons of patient characteristics and clinical course before and during the COVID-19 pandemic

Age, sex, and comorbidities did not differ significantly between the groups. However, the proportion of patients in each cause of admission changed (p = 0.031). The proportion of patients with respiratory disease increased during the COVID-19 pandemic (180 [29.1%] before vs. 187 [34.5%] during the pandemic, p = 0.050). The proportion of patients with other diseases decreased or remained unchanged. The severity indices of patients were significantly higher during than before the COVID-19 pandemic. The SAPS 3 was 65.9 ± 18.6 and 72.7 ± 20.3 (p < 0.001), the SOFA score on ER admission was 7.2 ± 4.2 and 8.1 ± 4.2 (p < 0.001), and the SOFA score on ICU admission was 6.8 ± 4.4 and 7.7 ± 4.4 (p = 0.001) before and during the pandemic, respectively (Table 1, Fig. 1b).

Compared to before the pandemic, the lengths of stay during the COVID-19 pandemic were longer in the ER (6.10 [4.11–9.58] h vs. 10.21 [7.21–19.43] h, p < 0.001), ICU (4 [2–7] days vs. 5 [2–10] days, p < 0.001), and hospital (10 [4–19] days and 12 [5–22] days, p = 0.044). Furthermore, more patients were intubated and mechanically ventilated (261 [42.2%] vs. 303 [55.9%], p < 0.001), and more patients signed a DNR order (111 [17.9%] vs. 141 [26.0%], p = 0.002) (Table 2).

Length of stay in the ER and changes in patient condition during emergency department care

We evaluated the changes in patient condition during ED care based on the changes in SOFA scores upon ER admission and ER discharge (or upon ICU admission) in each patient. Patients were then divided into three groups: those whose condition improved (decrease in SOFA score), those whose condition remained unchanged (unchanged SOFA score), and those whose condition deteriorated (increase in SOFA score). Prolonged ER stay was not related to the deterioration of patient condition during ED care; ER stay was longer in patients whose condition improved than in patients whose condition remained unchanged (Fig. 2b). Changes in conditions during ED care were significantly related to SAPS 3. Patients whose conditions deteriorated during ED care had significantly higher SAPS 3 than patients with unchanged or improved conditions, both before and during the COVID-19 pandemic (SAPS 3 of patients with an improved, unchanged, and deteriorated condition, respectively: 60.1 ± 16.8 vs. 66.5 ± 17.6 vs. 76.9 ± 20.0, p < 0.001, before the pandemic; 66.4 ± 18.9 vs. 73.1 ± 19.6 vs. 81.2 ± 22.1, p < 0.001, during the COVID-19 pandemic.) (Fig. 2c).

Characteristics of patients by changes in SOFA scores during emergency department care. (a) Patient numbers, (b) length of stay in the ER, and (c) SAPS 3 in each group. *p < 0.05, compared to the values in the patient group with unchanged SOFA scores. SOFA, Sequential Organ Failure Assessment; ER, emergency room; SAPS 3, Simplified Acute Physiology Score, version 3

COVID-19 pandemic and hospital mortality in propensity score-matched critically ill non-COVID-19 patients

Propensity score matching identified 397 patients in each group before and during the pandemic. Differences in baseline characteristics and clinical course, including severity indices, were minimized or disappeared after matching (Tables 1 and 2). In propensity score-matched patients, ICU and hospital mortality rates did not differ between the groups (121 [30.5%] and 141 [33.5%], p = 0.151; 131 [33.0] and 152 [38.3], p = 0.138). In the univariate logistic regression analysis, hospital mortality was related to age > 70 years, Charlson comorbidity score, cause of admission, SAPS 3, SOFA score upon ER and ICU admission, and presence of a DNR order. Both the length of stay in the ER (odds ratio [OR] 0.989, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.974–1.005, p = 0.167) and the COVID-19 pandemic (OR 1.260, 95% CI 0.942–1.685, p = 0.120) were not associated with hospital mortality. In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, risk of hospital mortality was increased by SAPS 3 (OR 1.065, 95% CI 1.048–1.081, p < 0.001), SOFA score at ER admission (OR 1.148, 95% CI 1.078–1.224, p < 0.001), and presence of a DNR order (OR 8.160, 95%CI 5.072–13.130, p < 0.001) (Table 3). The COVID-19 pandemic had no impact on hospital mortality in propensity score-matched critically ill patients in the multivariate logistic regression analysis (OR 1.405, 95% CI, 0.937–2.107, p = 0.100).

Discussion

We compared patient characteristics, clinical course, and mortality in non-COVID-19 critically ill patients before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. The baseline characteristics of these patients did not differ except for the cause of admission. During the COVID-19 pandemic, the severity of conditions was higher, the lengths of stay in the ER, ICU, and hospital were longer, and the ICU and hospital mortality rates were higher. However, hospital mortality did not differ between the propensity score-matched groups of patients before and during the pandemic. Only SAPS 3, SOFA score, and presence of a DNR order increased the risk of hospital mortality in the multivariate logistic regression analysis, whereas COVID-19 did not.

Korea is a country in which SARS-CoV-2 transmission is relatively well-controlled compared to other countries [12,13,14]. The daily incidence of COVID-19 in our country was 527 ± 85, and < 300 COVID-19 patients required ICU care in tertiary hospitals during the study period. However, we have experienced a shortage of intensive care resources in the ER and ICU [15, 16], which has affected not only COVID-19 patients but also non-COVID-19 patients [17]. Since the first patients were diagnosed with COVID-19 and the first surge of the disease occurred in Korea, the emergency medical system has changed. Patients with respiratory symptoms and/or fever were separated from other patients in the ER. This limited the capacity of the ER for patients with respiratory and/or infectious diseases who required medical services. A PCR test for SARS-CoV-2 was routine for all patients awaiting admission, which significantly increased the length of their stay in the ER. Moreover, temporary closure of certain zones of the ER that had been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 was common. Therefore, the turnover rate of beds in the ER decreased. The conditions of the ICU and intensive care system also changed. With the increase in the number of critically ill COVID-19 patients, many ICUs were allocated to patients with this contagious disease in isolation, according to government order; 1% of the total bed number was assigned to the COVID-19 ICUs in December 2020, which became 4% when the daily incidence exceeded 5000 cases [18]. Because COVID-19 patients were admitted to units completely isolated from non-COVID patients, these beds were not available to non-COVID-19 patients even when they were unoccupied. Although additional beds and facilities for critically ill COVID-19 patients were gradually provided, the number of ICU beds for non-COVID-19 patients decreased by 10 to 15 in each hospital included in this study during the study period. Furthermore, intensivists and critical care nurses were insufficient in number and difficult to recruit; therefore, the workload of these experienced practitioners increased [8, 19].

Outbreaks of infectious diseases can change the patterns of ER visits. More patients ignore significant medical signs and symptoms [9, 20]. However, the proportion of patients with febrile symptoms increased during the outbreak, while neither the proportion of critically ill patients—nor their mortality rates—changed [21, 22]. Our results showed a pattern similar to that reported previously. The proportion of patients with cardiovascular disease decreased, and the proportion of patients with respiratory disease increased during the pandemic, along with an increase in clinical severity.

Prolonged stays in the ER are known to influence patient mortality, owing to the shortage of critical care resources, including staff and equipment [23]. However, in our study, increased length of stay in the ER influenced the prognosis of the patients differently. Although prolonged stay in the ER did not directly impact the prognosis of patients, it increased the overall ER census and the threshold of ER admission. The decreased number of ICU beds and increased length of ICU stay during the pandemic also delayed ICU admission from the ER and caused prolonged stay in the ER, further increasing the ER census. Therefore, patients visited the ER in worse condition during the pandemic than those before, and the greater severity of critically ill patients at ER visit may have influenced their prognosis during this pandemic.

Owing to the large proportion of COVID-19 patients presenting with acute respiratory failure requiring critical care, the shortage of medical resources for critical care is expected. In this COVID-19 crisis, resource limitations impacted outcomes [24, 25]. Therefore, strategies for efficient allocation of available resources are essential. However, because the end of the crisis were not visible, a strategy is urgently needed for the efficient use of medical resources, including space, staff, and equipment [26].

This study had several limitations. First, we evaluated only patients admitted to the ICU via the ER. Our data did not include patients who were not admitted to the ICU from the ER, even those with high disease severity. Therefore, the results of this study cannot represent all critically ill patients who visit the ER. Second, the policy for managing patients in the ER differed among hospitals, which may have influenced the length of stay in the ER. Therefore, we calculated propensity score considering the length of stay in the ER and evaluated the association between the length of stay in the ER and patient mortality in propensity score-matched patients. Third, we screened patients during the same period in 2019 and 2021, considering the seasonal variance in the characteristics of patients admitted to the ICU. However, this study was not designed to investigate improvements in patient care and outcomes over 2 years. Fourth, we did not measure the difference in the quality of ICU care before and during the pandemic, which may have significantly influenced patient outcomes. Finally, due to the retrospective cohort design of the study, we can only comment on association of factors and not on causation of mortality of critically ill patients during the pandemic.

Conclusions

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the severity of patient conditions upon admission, as well as hospital mortality, were significantly higher than before the pandemic. However, in the propensity score-matched groups with similar severity indices, hospital mortality did not differ between the groups. The risk of hospital mortality in critically ill non-COVID-19 patients was not related to the COVID-19 pandemic, but to the severity indices of the patients and the DNR status. Although further study is needed, delayed access to medical services may be related to higher severity and mortality in non-COVID-19 critically ill patients. Establishing a strategy to manage medical resources is needed to halt the interaction between delayed access to medical services and poor outcomes in critically ill patients.

Availability of data and materials

The data set supporting the results of this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- COVID-19:

-

Coronavirus disease-2019

- SARS-CoV-2:

-

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- ER:

-

Emergency room

- ED:

-

Emergency department

- SAPS 3:

-

Simplified Acute Physiology Score, version 3

- SOFA:

-

Sequential Organ Failure Assessment

- DNR:

-

Do-not-resuscitate

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

References

Ganyani T, Kremer C, Chen D, Torneri A, Faes C, Wallinga J, et al. Estimating the generation interval for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) based on symptom onset data, March 2020. Euro Surveill. 2020;25:2000257.

Islam N, Shkolnikov VM, Acosta RJ, Klimkin I, Kawachi I, Irizarry RA, et al. Excess deaths associated with COVID-19 pandemic in 2020: age and sex disaggregated time series analysis in 29 high income countries. BMJ. 2021;373: n1137.

Huang C, Wang Y, Li X, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan. China Lancet. 2020;395:497–506.

Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City area. JAMA. 2020;323:2052–9.

Bhatraju PK, Ghassemieh BJ, Nichols M, et al. Covid-19 in critically ill patients in the Seattle region: case series. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2012–22.

Grasselli G, Pesenti A, Cecconi M. Critical care utilization for the COVID-19 outbreak in Lombardy, Italy: early experience and forecast during an emergency response. JAMA. 2020;323:1545–6.

Anesi GL, Lynch Y, Evans L. A conceptual and adaptable approach to hospital preparedness for acute surge events due to emerging infectious diseases. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2:e0110.

Wahlster S, Sharma M, Lewis AK, Patel PV, Hartog CS, Jannotta G, et al. The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic’s effect on critical care resources and health-care providers: a global survey. Chest. 2021;159:619–33.

Trabattoni D, Montorsi P, Merlino L. Late STEMI and NSTEMI patients’ emergency calling in COVID-19 outbreak. Can J Cardiol. 2020;36:1161.e7-1161.e8.

Kerlin MP, Costa DK, Davis BS, Admon AJ, Vranas KC, Kahn JM. Actions taken by US hospitals to prepare for increased demand for intensive care during the first wave of COVID-19: a national survey. Chest. 2021;160:519–28.

Kim JH, Hong SK, Kim Y, Ryu HG, Park CM, Lee YS, et al. Experience of augmenting critical care capacity in Daegu during COVID-19 incident in South Korea. Acute Crit Care. 2020;35:110–4.

Ryu S, Chung S. Kora’s early COVID-19 response Findings and implications. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(16):8316.

Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Coronavirus disease-19 main website. http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/en/. Accessed 27 Dec 2021.

Jeong GH, Lee HJ, Lee J, Lee JY, Lee KH, Han YJ, et al. Effective control of COVID-19 in South Korea: cross-sectional study of epidemiological data. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22: e22103.

Lee K. Rapid communication for effective medical resource allocation in the COVID-19 pandemic. Acute Crit Care. 2021;36:262–3.

Park S. Can the intensivists predict the outcomes of critically ill patients on the appropriateness of intensive care unit admission for limited intensive care unit resources? Acute Crit Care. 2021;36:388–9.

Santi L, Golinelli D, Tampieri A, Farina G, Greco M, Rosa S, et al. Non-COVID-19 patients in times of pandemic: emergency department visits, hospitalizations and cause-specific mortality in Northern Italy. PLoS ONE. 2021;16: e0248995.

Ministry of Health and Welfare. Plan of beds expansion for critically ill COVID-19 patients. http://ncov.mohw.go.kr/tcmBoardView.do?brdId=&brdGubun=&dataGubun=&ncvContSeq=368796&contSeq=368796&board_id=&gubun=ALL [updated 08 12 2021]. Accessed 15 Mar 2022.

Anesi GL, Kerlin MP. The impact of resource limitations on care delivery and outcomes: routine variation, the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, and persistent shortage. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2021;27:513–9.

Metzler B, Siostrzonek P, Binder RK, Bauer A, Reinstadler SJ. Decline of acute coronary syndrome admissions in Austria since the outbreak of COVID-19: the pandemic response causes cardiac collateral damage. Eur Heart J. 2020;41:1852–3.

Lee SY, Khang Y-H, Lim H-K. Impact of the 2015 Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak on emergency care utilization and mortality in South Korea. Yonsei Med J. 2019;60:796–803.

Jeong H, Jeong S, Oh J, Woo SH, So BH, Wee JH, et al. Impact of Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak on the use of emergency medical resources in febrile patients. Clin Exp Emerg Med. 2017;4:94–101.

Boudi Z, Lauque D, Alsabri M, Östlundh L, Oneyji C, Khalemsky A, et al. Association between boarding in the emergency department and in-hospital mortality: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2020;15: e0231253.

Gabler NB, Ratcliffe SJ, Wagner J, Asch DA, Rubenfeld GD, Angus DC, Halpern SD. Mortality among patients admitted to strained intensive care units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188:800–6.

Wilcox ME, Harrison DA, Patel A, Rowan KM. Higher ICU capacity strain is associated with increased acute mortality in closed ICUs. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:709–16.

Aziz S, Arabi YM, Alhazzani W, Evans L, Citerio G, Fischkoff K, et al. Managing ICU surge during the COVID-19 crisis: rapid guidelines. Int Care Med. 2020;46:1303–25.

Funding

This study was supported by Korea University Ansan Hospital Grant K2212071.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SK contributed to the data acquisition and analysis and drafted the manuscript. HC contributed to the statistical analysis. JKS contributed to data acquisition and WJJ contributed to data acquisition and interpretation. YSL contributed to the data acquisition and interpretation. JHK contributed to the study conception and design, and substantively revised the draft. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Korea University Ansan Hospital approved the study protocol and waived the requirement for informed consent (IRB No. 2021AS0291).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kim, S., Choi, H., Sim, J.K. et al. Comparison of clinical characteristics and hospital mortality in critically ill patients without COVID-19 before and during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multicenter, retrospective, propensity score-matched study. Ann. Intensive Care 12, 57 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-022-01028-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-022-01028-2