Abstract

Background

The pandemic situation due to COVID-19 highlighted the importance of global health security preparedness and response. Since the revision of the International Health Regulations (IHR) in 2005, Joint External Evaluation (JEE) and States Parties Self-Assessment Annual Reporting (SPAR) have been adopted to track the IHR implementation stage in each country. While national IHR core capacities support the concept of Universal Health Coverage (UHC), there have been limited studies verifying the relationship between the two concepts. This study aimed to investigate empirically the association between IHR core capacity scores and the UHC service coverage index.

Method

JEE score, SPAR score and UHC service coverage index data from 96 countries were collected and analyzed using an ecological study design. The independent variable was IHR core capacity scores, measured by JEE 2016-2019 and SPAR 2019 from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the dependent variable, UHC service coverage index, was extracted from the 2019 UHC monitoring report. For examining the association between IHR core capacities and the UHC service coverage index, Spearman’s correlation analysis was used. The correlation between IHR core capacities and UHC index was demonstrated using a scatter plot between JEE score and UHC service coverage index, and the SPAR score and UHC service coverage index were also presented.

Result

While the correlation value between JEE and SPAR was 0.92 (p < 0.001), the countries’ external evaluation scores were lower than their self-evaluation scores. Some areas such as available human resources and points of entry were mismatched between JEE and SPAR. JEE was associated with the UHC score (r = 0.85, p < 0.001) and SPAR was also associated with the UHC service coverage index (r = 0.81, p < 0.001). The JEE and SPAR scores showed a significant positive correlation with the UHC service coverage index after adjusting for several confounding variables.

Conclusion

The study result supports the premise that strengthening national health security capacities would in turn contribute to the achievement of UHC. With the help of the empirical result, it would further guide each country for better implementation of IHR.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recent threats to global health security, including influenza A H1N1 (2009), Ebola virus disease (2014), MERS-Cov (2015), Zika virus disease (2016), and COVID-19 (2019), have emphasized the importance of strengthening global health security capacities more than ever. The International Health Regulations (IHR) 2005 provide an overarching legal framework designed to help countries build prevention, detection, and response capacities to deal with public health risks. The IHR has committed World Health Organization (WHO) member states to participate in international surveillance networks by reviewing and implementing sound surveillance strategies that contribute to global outbreak intelligence [1].

As 196 countries, including 194 WHO member states, agreed to report the implementation of the IHR to the World Health Assembly (Resolution WHA 58.3) [2], the IHR Monitoring and Evaluation Framework was then adopted to report their progress in implementing IHR. The two key features of the IHR Monitoring and Evaluation Framework are mandatory States Parties Self-Assessment Annual Reporting (SPAR) and voluntary Joint External Evaluation (JEE) [3]. The SPAR tool consists of 13 capacities and is an annual self-assessment tool, while the JEE tool evaluates 19 technical areas and is recommended to be done every 4-5 years. Despite these differences, both SPAR and JEE have similar structures and are complementary to each other for evaluating IHR core capacities [3, 4].

Understanding the mutual relationship to reinforce global health security capacities and UHC is a recent, yet crucial concept for creating synergistic effects [1, 5]. Previous studies have attempted to analyze whether the technical components of the IHR core capacity scores converge to each other, whether they contribute to IHR implementation, and whether their evaluation reflects the actual global health security capacity level [6,7,8,9]. Previous research also reports lessons learned for IHR implementation and the possible mechanisms for IHR implementation [10, 11]. One study comparing global health security and UHC showed a significant relationship between the two indices [12]. However, there have been limited and controversial studies on the relationship between IHR core competencies and UHC.

Therefore, this study first aims to examine the global distribution and association between the JEE score and SPAR score to determine whether one could represent the other. Second, the study examines the differences between IHR core capacity scores (JEE score and SPAR score) and the UHC service coverage index. Third, the study analyzes the association between IHR core capacity scores and the UHC service coverage index to provide empirical evidence on the two global health agendas.

Methods

Study design

An ecological study design was used in this study to investigate the correlation between IHR core capacity scores and the UHC service coverage index (Fig. 1). The study is based on analyses of data collected from 96 countries for JEE, SPAR, and the UHC service coverage index. The IHR core capacity scores, which were measured by JEE 2016-2019 and SPAR 2019 from the World Health Organization (WHO), were used as independent variables. The dependent variable, i.e., the UHC service coverage index, was extracted from the 2019 UHC monitoring report.

This study identified the confounding variables that may affect UHC service coverage. This study selected the confounding variables that may affect UHC service coverage. UHC supports the idea that health service is available to everyone without causing financial hardship. Tracking the progress towards UHC uses two specific indicators, health services coverage and financial risk protection coverage. Previous studies on UHC identified that socio-demographic index, government health expenditure and governance show positive association with UHC service coverage. The selection principle of confounding variables is related to both core explanatory variables and dependent variables. Thus, the confounding variables in this study include GDP per-capita, current health expenditure, infant mortality rate, life expectancy at birth, hospital beds, medical doctors, nursing and midwifery personnel, population ages under five, population ages 65 and above [9, 10].

Four models were demonstrated to understand the factors of JEE and other independent variables affecting UHC service coverage, and SPAR and other independent variables affecting UHC service coverage. Model 1 includes the global health security index of either JEE or SPAR overall mean score and population variables (population age under five, population age 65 and above) as independent variables, Model 2 incorporates the variables used in Model 1 and economic variables (GDP per capita, current health expenditure), model 3 includes the variables used in model 2 and variables related to medical resources (hospital beds, medical doctors, nursing, and midwifery personnel), and Model 4 includes the variables used in Model 3 and variables related to health status (infant mortality rate, life expectancy at birth).

Country data

JEE 2016-2019, SPAR 2019, and UHC service coverage index 2017 data from 1st March, 2021 to 31st March, 2021 were extracted [13,14,15]. Online databases from the World Bank, WHO Global Health Observatory, and United Nations provided GDP per capita, current health expenditure, infant mortality rate, life expectancy at birth, hospital beds, medical doctors, nursing and midwifery personnel, population age under five, population age 65 and above. GDP per capita, current health expenditure, and infant mortality rates were available from the World Bank [16,17,18]. Data on life expectancy at birth, hospital beds, medical doctors, and nursing and midwifery personnel were available from the WHO Global Health Observatory [19,20,21,22]. The United Nations website was the other source of data for population age under five and population age 65 and above [23, 24] (Table 1).

The JEE tool contains 19 technical areas, represented by 48 indicators. Each technical area represents the mean scores of the indicators. The indicator’s scoring system is based on a five-point ordinal scale from 1 to 5, reflecting higher capacity as the score increases. The SPAR tool consists of 24 indicators from the 13 IHR capacities needed to detect, assess, notify, and respond to public health events of national and international concern. The level of SPAR is expressed as the average of all indicators, which are calculated as a percentage of performance based on a scale of 1 to 5. Recognizing the conceptual similarities between JEE and SPAR, the technical areas were matched and categorized into 15 areas. The overall mean values of JEE and SPAR were retrieved and used for the statistical analysis, except for the spider diagram comparing JEE and SPAR, where the value of JEE was multiplied by 20 to ensure that both JEE and SPAR could have the same scale.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 25.0. A spider diagram was used to visually explain the relationship between the JEE and SPAR scores. The correlation analysis between JEE and SPAR further supported this relationship. Furthermore, Pearson correlation analysis was used to test the association between the IHR core capacity scores and the UHC service coverage index. Descriptive analysis and one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) were used to describe the general characteristics of the selected countries and compare the JEE scores, SPAR scores, and the UHC service coverage index by population, economic index, human resources for health, and health indicators of countries. The scatterplots between the JEE score and the UHC service coverage index, as well as the SPAR score and the UHC service coverage index, were presented to support this relationship. Lastly, multiple regression analysis was used to test the effect of the IHR core capacity scores on the UHC service coverage index. We used a variance inflation factor (VIF) to confirm that multicollinearity did not occur between the explanatory variables (VIF < 10). The level of statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

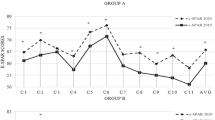

The global distribution of JEE and SPAR scores (Fig. 1) shows similar patterns between the JEE and SPAR scores. SPAR and JEE scores were compared by matching the variables of the two assessment tools based on their contextual similarities. With the lowest r-value as 0.514 and the highest r-value as 0.786, a significant relationship between JEE and SPAR was identified (Table 2). While the response and radiation areas converged in the spider diagram, overall, the JEE score was more conservative than the SPAR score (Fig. 2).

The 96 countries were relatively evenly distributed by GDP per capita for high income (21.9%), upper-middle income (20.8%), lower-middle income (33.3%), and low income (22.9%) groups. Twenty-three (24%) of the analyzed countries showed less than 4% of health expenditure in GDP, and 51 (53.1%) showed a health expenditure percentage between 4.01 and 8% (Table 3).

Table 3 shows multiple disparities in IHR core capacity scores and the UHC service coverage index. There was a significant difference (p < 0.05) between JEE, SPAR, and UHC service coverage in all groups except current health expenditure, i.e., GDP per capita, infant mortality rate, life expectancy at birth, hospital beds, medical doctors, nursing and midwifery personnel, population age under 5, and population age 65 and above. The JEE and UHC service coverage were significant in current health expenditure, while SPAR was not significant. In JEE and UHC service coverage, the F statistic was the highest in the GDP per-capita (60.43 and 77.67) and the lowest in the current health expenditure (3.05 and 3.11), respectively. In SPAR, the highest F statistic was GDP per capita (46.63), and the lowest was hospital beds (6.82).

The scatter plots of JEE and SPAR scores in relation to the UHC service coverage index were positively associated with the UHC service coverage index (Fig. 3). Multiple regression analysis was then performed using the four models. JEE affected UHC service coverage in all four models, while the effect of SPAR was valid in only three models. JEE scores, together with population, economic resources, health resources, and health status variables, affected the UHC service coverage index. The variables in Model 4 could explain 85.9% (adjusted R2 = 0.859, β = 0.275, p < 0.001) of the variance in UHC service coverage when JEE was taken as an independent variable. It showed that SPAR, together with population, economic resources, and health resources, affects UHC service coverage. The variables in Model 3 could explain 82.3% (adjusted R2 = 0.823, β = 0.240, p < 0.001) of the variance in UHC service coverage when SPAR was taken as an independent variable. However, SPAR was not valid in Model 4 (Table 4).

Discussion

This study showed a significant association between JEE and SPAR; at the same time, lower JEE scores compared to SPAR scores were identified. In addition, a strong association between IHR core capacities and UHC service coverage was demonstrated using empirical data. All four models using JEE as the independent variable were valid, while only three models that used SPAR as an independent variable were valid.

Several studies have reported similar findings in terms of the relationship between JEE and SPAR. While not completely converging, the indicators of JEE and SPAR show a high level of correlation when mapped together [3, 12, 25, 26]. Considering the complementary functions of JEE and SPAR, they are both relevant to each other and are representative of the IHR core capacity scores. As identified in the study, similarities and differences were found between JEE and SPAR in the spider diagram (Fig. 2). Indeed, gaps exist between the data due to errors in matching the contextual similarities. Although indicators of JEE and SPAR are presented with identical keywords, they are likely to assess different aspects of IHR core capacity. At the same time, it can also be argued that the gaps are not significant, as can be seen in Fig. 3, meaning that they can be neglected.

Only recently has it been brought to attention by the global public health community that global health security is an integral part of public health functions [1]. The global response to the earlier infectious disease outbreaks gave us a lesson that preparedness and response to public health threats require intra-sectoral approaches, including governance, incident management, public health, health care, logistics, sociocultural and community initiatives, and global response [27]. A systematic review that analyzed the link between the Ebola outbreak and health systems concluded that ensuring an adequate and efficient health workforce, a strong health system, adequate service delivery, health financing and management, leadership, and governance all affected the countries’ performance regarding the Ebola disease outbreak [28]. In short, the preparedness and response to public health crises requires strengthening health systems and inter-sectoral approaches, which in turn contribute to improving global health security and achieving UHC.

Since an ecological study was performed here, the collected data were useful to explore the association between JEE and SPAR, and the association between global health security and UHC [29]. However, there is no effective way of taking into account or adjusting for other factors that influence the outcome. As a result, an apparent correlation between JEE and SPAR, and global health security and UHC could be misleading. It should be noted that all factors cannot be adjusted in the ecological study because in the real world, all known and unknown factors affect the dependent variable. Therefore, future studies should analyze the effects of the health system on global health security and on UHC, and analyze whether the health system has moderating effects.

Other possible limitations include reporting bias, as the study results are based on the data reported by each country, and data have been retrieved from various institutions and websites. Detection bias might have also affected the results because exact mechanisms between global health security capacity and UHC were not identified in the study; there might be some variables affecting them. Time bias could be another source of limitation because the data were not collected at the same time. However, this study used the latest data to analyze the results, to minimize reporting and time bias; each result was carefully reviewed to keep the risk of detection bias low.

While this study is prone to reporting, detection, and time bias, it is still reliable enough to explain the relationship between JEE and SPAR, and between IHR core capacity scores and UHC, with the empirical data. The study results support the premise that the two global agendas, global health security and UHC, do not stand alone, but are mutually interconnected. Focusing on one agenda would lead to inappropriateness in providing health services to the population without financial hardship, and preparing and responding to global health risks. Previous research has shown a strong correlation between JEE, health outcomes, and the function of the health system. Therefore, embedding global health security into UHC is crucial; global health security needs to be integrated with the health system [8, 5, 25, 30,31,32,33]. In addition, the JEE and SPAR are complementary to each other, and it is important to ensure that they maintain a certain level of convergence.

Conclusion

Achieving UHC requires regional, national, and international efforts in health, social, and cross-cutting areas. This research attempted to verify the correlation between global health security capacity and UHC using data from 96 countries regarding JEE score, SPAR score, and the UHC service coverage index. The results showed that JEE and SPAR are strongly associated with UHC. However, the specific mechanism of how preparedness, detection, and response criteria of JEE and SPAR affect UHC remains a topic that needs to be addressed.

There is inadequate global preparedness for health security, and no country or region is fully prepared for global health security. Ensuring global health security requires prevention, detection, and response to emergencies at the national, regional, and global levels. The aspiration for global health security will not be realized without UHC; hence, the tension between global health security and UHC should be transformed into synergistic planning, financing, and implementation, through a diagonal investment and service delivery approach, including differentiated, integrated, and community-led services. In doing so, the health system and policies should be strengthened to ensure the implementation of IHR and achieving UHC.

Abbreviations

- JEE:

-

Joint External Evaluation

- SPAR:

-

Self-Assessment Annual Reporting

- UHC:

-

Universal Health Coverage

References

Kluge H, Martín-Moreno JM, Emiroglu N, Rodier G, Kelley E, Vujnovic M, et al. Strengthening global health security by embedding the International Health Regulations requirements into national health systems. BMJ global health. 2018;3(S1):e000656, 1-7.

Pan American Health Organization (PAHO). International Health Regulations (IHR) - PAHO/WHO [Internet]. [cited 11 Aug 2021]. Available from: https://www.paho.org/en/international-health-regulations-ihr.

Razavi A, Collins S, Wilson A, Okereke E. Evaluating implementation of International Health Regulations core capacities: using the Electronic States Parties Self-Assessment Annual Reporting Tool (e-SPAR) to monitor progress with Joint External Evaluation indicators. Globalization and Health. 2021;17(1):1–7.

World Health Organization (WHO). International Health Regulations (2005) - IHR Monitoring and Evaluation Framework [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2018 [cited 11 Aug 2021].

World Health Statistics 2017: Monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2017 [cited 11 Aug 2021]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/255336.

Menon AN, Rosenfeld E, Brush CA. Law and the JEE: Lessons for IHR Implementation. Health Secur. 2018;16(S1):S11–S17.

Haider N, Yavlinsky A, Chang YM, Hasan MN, Benfield C, Osman AY, et al. Y. The Global Health Security index and Joint External Evaluation score for health preparedness are not correlated with countries' COVID-19 detection response time and mortality outcome. Epidemiol Infect. 2020;148(e210):1–8.

Gupta V, Kraemer JD, Katz R, Jha AK, Kerry VB, Sane J, et al. Analysis of results from the joint external evaluation: examining its strength and assessing for trends among participating countries. J Glob Health. 2018;8(2):e020416, 1–9.

Forzley M. Global Health Security Agenda: joint external evaluation and legislation—a 1-year review. Health Secur. 2017;15(3):312–9.

Tsai FJ, Katz R. Measuring global health security: comparison of self-and external evaluations for IHR core capacity. Health Secur. 2018;16(5):304–10.

Talisuna A, Yahaya AA, Rajatonirina SC, Stephen M, Oke A, Mpairwe A, et al. Joint external evaluation of the International Health Regulation (2005) capacities: current status and lessons learnt in the WHO African region. BMJ Glob Health. 2019;4(6):e001312, 1–8.

Assefa Y, Hill PS, Gilks CF, Damme WV, Pas RVD. Woldeyohannes S, et al. Global health security and universal health coverage: Understanding convergences and divergences for a synergistic response. PLoS One. 2020;15(12):e0244555.

World Health Organization (WHO). Joint External Evaluation (JEE) mission reports [Internet]. [cited 13 Jan 2021]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/ihr/procedures /mission-reports/en/.

World Health Organization (WHO). State Party Annual Report (SPAR) [Internet]. [cited 24 Jan 2021]. Available from: https://extranet.who.int/e-spar.

World Health Organization (WHO). Primary health care on the road to universal health coverage: 2019 monitoring report [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2019 [cited 24 Jan 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/healthinfo/universal_health_coverage/report/uhc_report_2019.pdf.

World Bank. GDP per capita (current US$) [Internet]. World Bank; 2019 [cited 18 April 2021]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD.

World Bank. Current health expenditure (% of GDP)[Internet]. World Bank; 2018 [cited 18 April 2021]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SH.XPD.CHEX.GD.ZS.

World Bank. Infant mortality rate (deaths per 1,000 live births) [Internet]. World Bank; 2019 [cited 18 April 2021]. Available from: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.IMRT.IN.

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Global Health Observatory. Life expectancy at birth (years) [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2020 [cited 18 April 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators.

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Global Health Observatory. Hospital beds (per 10,000 population) [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2020 [cited 18 April 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators.

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Global Health Observatory. Medical doctors (per 10,000 population) [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2021 [cited 18 April 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators.

World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Global Health Observatory. Nursing and midwifery personnel (per 10,000 population) [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2021 [cited 18 April 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/indicators.

United Nations (UN). Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Population ages under 5 (% of total population) [Internet]. United Nations; 2019 [cited 18 April 2021]. Available from: https://population.un.org/wpp2019/Download/Standard/Population/.

United Nations (UN). Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Population ages 65 and above (% of total population) [Internet]. United Nations; 2019 [cited 18 April 2021]. Available from: https://population.un.org/wpp2019/Download/Standard/Population/.

Mondiale de la Santé O, World Health Organization. Improvement in annual reporting of self-assessments to the International Health Regulations (2005). Weekly Epidemiological Record= Relevé épidémiologique hebdomadaire. 2019;94:iii–viii.

Tsai FJ, Tipayamongkholgul M. Are countries’ self-reported assessments of their capacity for infectious disease control reliable? Associations among countries’ self-reported international health regulation 2005 capacity assessments and infectious disease control outcomes. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–9.

Chamberlin M, Okunogbe A, Moore M, Abir M. Intra-action report – a dynamic tool for emergency managers and policymakers. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation; 2015.

Shoman H, Karafillakis E, Rawaf S. The link between the West African Ebola outbreak and health systems in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone: a systematic review. Globalization Health. 2017;13(1):1–22.

Barratt H, Kirwan M, Shantikumar S. Epidemiology [Internet]. Health Knowledge; 2018 [cited 11 Aug 2021]. Available from: https://www.healthknowledge.org.uk/public-health-textbook/research-methods/1a-epidemiology/descriptive-studies-ecological-studies.

World Health Organization (WHO). Building health systems resilience for universal health coverage and health security during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond: a brief on the WHO position [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2021 [cited 11 Aug 2021]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-UHL-PHC-SP-2021.01.

Erondu NA, Martin J, Marten R, Ooms G, Yates R, Heymann DL. Building the case for embedding global health security into universal health coverage: a proposal for a unified health system that includes public health. The Lancet. 2018;392(10156):1482–6.

Lal A, Erondu NA, Heymann DL, Gitahi G, Yates R. Fragmented health systems in COVID-19: rectifying the misalignment between global health security and universal health coverage. The Lancet. 2021;397(10268):61–7.

World Health Organization (WHO). Regional Office for the Western Pacific. Asia Pacific strategy for emerging diseases and public health emergencies (APSED III): advancing implementation of the International Health Regulations (2005): working together towards health security [Internet]. Manila: WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific; 2017 [cited 11 Aug 2021]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/259094.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to National Research Foundation of Korea for supporting the study. We would like to express our special acknowledgement to research assistants, Ms. Jiwon Park and Ms. Yejin Lee, who supported data collection and coding, and Ms. Tae Hyeong Lim for drawing figure by geographical information system. Also, we would like to thank Editage (www.editage.co.kr) for English language editing.

Funding

This study has been funded by National Research Foundation of Korea (No: 2020S1A5A8047653). Funders were not involved in the design of the study nor the collection, analysis, interpretation of data or writing of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YR initiated and designed the study, advised on the method and analysis, and revised the draft. SW and JJ interpreted the data analysis and wrote the manuscript. SE and JJ collected the data and conducted statistical analysis. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Lee, Y., Kim, S., Oh, J. et al. An ecological study on the association between International Health Regulations (IHR) core capacity scores and the Universal Health Coverage (UHC) service coverage index. Global Health 18, 13 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-022-00808-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12992-022-00808-6