Abstract

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) remains one of the infectious diseases with a leading cause of death among adults worldwide. Metformin, a first-line medication for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, may have potential for treating TB. The aims of the present systematic review were to evaluate the impact of metformin prescription on the risk of tuberculosis diseases, the risk of latent TB infection (LTBI) and treatment outcomes of tuberculosis among patients with diabetic mellitus.

Methods

Databases were searched through March 2019. Observational studies reporting the effect of metformin prescription on the risk and treatment outcomes of TB were included in the systematic review. We qualitatively analyzed results of included studies, and then pooled estimate effects with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of different outcome using random-effect meta-analyses.

Results

This systematic review included 6980 cases from 12 observational studies. The meta-analysis suggested that metformin prescription could decrease the risk of TB among diabetics (pooled odds ratio [OR], 0.38; 95%CI, 0.21 to 0.66). Metformin prescription was not related to a lower risk of LTBI (OR, 0.73; 95%CI, 0.30 to 1.79) in patients with diabetes. Metformin medication during the anti-tuberculosis treatment is significantly associated with a smaller TB mortality (OR, 0.47; 95%CI, 0.27 to 0.83), and a higher probability of sputum culture conversion at 2 months of TB disease (OR, 2.72; 95%CI, 1.11 to 6.69) among patients with diabetes. The relapse of TB was not statistically reduced by metformin prescription (OR, 0.55; 95%CI, 0.04 to 8.25) in diabetics.

Conclusions

According to current observational evidence, metformin prescription significantly reduced the risk of TB in patients with diabetes mellitus. Treatment outcomes of TB disease could also be improved by the metformin medication among diabetics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Tuberculosis (TB) remains one of the infectious diseases with a leading cause of death among adults worldwide [1]. According to a global report from WHO, an estimated 10 million people became newly sick with TB in 2017 [1, 2]. The treatment of TB mainly depends on the special anti-TB regimen involving multiple medications. Notably, the regimen is well known for a long duration and inevitable drug side effects, which results in poor adherence to medication, and further leads to the emergence of drug resistance [3]. Given the current situation, alternative anti-TB drugs with minimal drug toxicity are needed to drive the anti-TB regimen more safe and effective.

Metformin, a first-line medication for the treatment of type 2 diabetes, showed the potential for an anti-TB treatment in recent studies [3,4,5,6,7,8]. The drug was a widely used therapy among diabetics with limited adverse events. Even a small anti-TB effect of metformin could make great sense to the treatment of TB. Metformin may shorten the standard course of anti-TB therapy and reduce the probability of drug resistance. Metformin could limit the intracellular growth of Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Mtb) through an AMPK (adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase)-dependent passway [4, 5]. Observational studies [9, 10] demonstrated that metformin prescription might reduce the risk of TB or latent TB infection in people with diabetes, and the studies [7, 11,12,13] also suggested that metformin presented an inspiring anti-TB trend on various treatment outcomes, such as increased TB treatment success, lower TB mortality, and enhanced sputum culture conversion [14]. Existing evidence seemed to sketch an antituberculotic role of metformin. However, whether metformin prescription affect the risk and treatment of TB is still nebulous.

To clarify the relationship between metformin and TB, we conducted this systematic review of observational studies (1) to summarize epidemiological evidence on the association between metformin and TB disease; (2) to figure out whether metformin prescription could reduce the risk of TB or LTBI among patients with diabetes mellitus (DM); and (3) to explore the effects of metformin prescription on the treatment outcomes of TB in diabetics.

Methods

Definitions

In this systematic review, latent TB infection (LTBI) represented an asymptomatic TB infection status which could be diagnosed by interferon gamma release assays. TB disease was regarded as a state of TB infection that was symptomatic and was identified in medical institutions.

Search strategy

The protocol was registered in the PROSPERO database (CRD42019132085). We performed the research in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) 2009 guidelines (see Additional file 1). We identified observational studies reporting an effect of metformin prescription on the risk and treatment of TB disease. We identified eligible studies in Pubmed, Embase, and Scopus through database inception up to March 2019. Following search keywords were used to grab relevant studies: (1) tuberculosis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, anti-tuberculosis, and their synonyms; (2) metformin and its other titles. The complete search strategy in details was available in the Additional file 2. The language was not limited throughout the search. References of relevant studies, if necessary, were manually checked to avoid omitting eligible studies.

Study selection

Cohort, case-control, or cross-sectional studies exploring the impact of metformin on the risk of TB and the anti-TB therapy were included to make a full-text assessment. To fully exploit existing evidence on the association between metformin and TB, we broadened the scope of PECO (population, exposure, comparator, and outcome) framework in inclusion criteria: population was not limited; comparator could be healthy controls and patients using other antidiabetic drugs; exposure was restricted as metformin prescription; outcome could be a new diagnosis of TB disease in diabetics or indicators for the treatment of TB among patients. The main endpoints for this research were the TB-oriented composite endpoint (a new diagnosis of active TB or LTBI) and the patient-oriented composite endpoint of treatment outcomes (TB mortality, sputum culture conversion, relapse rate, and pulmonary cavities). In line with endpoints, two groups of people were included: if studies examined the risk of TB disease, their population should be diabetics without TB originally; if studies analyzed the treatment indicators, the population was patients with both DM and TB disease. We did not set any specific exclusion criteria in the selection procedure.

Data extraction

We extracted the following data from eligible studies: (1) authors, (2) published year, (3) study location, (4) study design, (5) definite description and number of participants, (6) definition of exposure, (7) definition of outcomes, (8) definition of control group, (9) exact number of cases, (10) relevant findings, and (11) covariates adjusted in data processing.

Two investigators (XY and LL) reviewed the full-length article and extracted data from retrieved studies independently. Discrepancies in data extraction were discussed throughout the process until authors reached a mutual consensus. If necessary, we tried to contact the corresponding author of relevant articles for more information.

Quality appraisal

Considering that researches were all observational, we used the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) to assess the methodological quality of studies. In this research, we prepared three individual scales for cohort studies, case-control studies, and cross-sectional studies respectively. The scale for the cross-sectional study was a form specially modified for the research, and it was originally used by Fralick and colleagues [15]. Overall, quality appraisal covers three individual perspectives (the population selection; the comparability in study design; and the ascertainment of outcome or exposure). Two reviewers (XF and FC) performed the assessment separately and a senior reviewer (SC) resolved disagreements.

Data management and statistical analyses

Our primary goal was to summarize existing epidemiological evidence of the impact of metformin on TB disease. Thus, characteristics, study framework, and findings of eligible studies were markedly collected and qualitatively analyzed. On the basis of qualitative material, we tried to pool estimate effects in meta-analyses from two perspectives: one kind reported a risk of TB in patients with metformin usage versus no metformin usage, and the other analyzed effects of metformin on varied TB treatment outcomes, such as increased TB treatment success, lower TB mortality, and enhanced sputum culture conversion.

In the analysis of onset risk, we inspected the data source along with the study period, and further selected partial researches in meta-analysis to avoid duplication of crowd data, producing a high-grade and credible result. Considering the impacts of metformin on the anti-TB treatment are diverse, we evaluated the findings of treatment outcomes separately. On the grounds that the therapeutic effect of drugs on a definite disease could only be confirmed by strictly designed clinical trials, we had not conducted an indirect comparison between different types of treatment outcomes, which was unnecessary and inefficient. Instead, we depicted the study framework and outcomes in a well-designed table to display the current status on this topic, and we merged the same type of results to generate pooled results.

We conducted random-effects meta-analyses to combine the estimates from selected researches reported as hazard ratios (HRs), odds ratios (ORs) and relative risks (RRs). Since TB incidence was low in studies, we regarded RRs as similar approximations of OR and merged them with HRs, resulting in a common estimate effect of OR [16]. If an article included more than one study, we deconstructed the studies separately. Due to the limited studies in a single meta-analysis, sensitivity analysis and publication bias assessment were not planned. Heterogeneity of the study-specific estimates was assessed with the Cochran’s Q test and I2 statistics (0–100%), and I2 < 50% was regarded as low heterogeneity, I2 value 50 to 75% as moderate heterogeneity, I2 > 75% as substantially high heterogeneity [17]. All P-values were two-tailed and P < 0.05 was used to define the significant level. Statistical analyses in this research were performed on Stata version 14.0.

Results

Study characteristics and quality appraisal

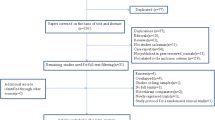

The literature searching strategy of this systematic review was displayed in Fig. 1. A pilot research [4] and a cross-sectional study [18] used the same data set, and we chose the former to analyze the overlapped data. Thus, eleven individual articles [4, 7,8,9,10,11,12,13, 19,20,21] with 12 studies satisfying inclusion criteria were identified in the systematic review, and study characteristics were reported in Table 1. Cases, controls and outcomes of each study were carefully extracted and inspected. Of 12 eligible studies, one was a case-control design study, one was of cross-sectional design, and the rest were retrospective cohort studies. Sample sizes ranged from 58 to 177,732. Six studies were from Taiwan, and one from U.S.A., India, South Korea, Singapore, China (mainland) respectively. The participants were patients with DM for 8 studies investigating the risk of TB or LTBI, and diabetics with TB for 4 studies discussing the treatment outcomes of TB disease. The outcomes for TB treatment were as follows: (1) sputum culture conversion, (2) relapse of TB, (3) TB mortality, (4) success treatment, and (5) number of pulmonary cavities. The methodological quality of included studies was fully assessed and manifested in Table 2. All studies had moderate to high quality (NOS quality score ≥ 6). To better present study framework, we summarized basic characteristics in Table 3. Overall, ten studies showed a statistical significant anti-TB effect of metformin, while the other two were the opposite.

Metformin prescription and the risk of TB disease

Six studies [7, 9, 10, 13, 19, 20] carrying 5273 cases advocated a reduced risk of TB among metformin users compared to non-users, five of which were performed using the same database (National Health Insurance Research Database from Taiwan). To avoid repeated analysis of crowd data, we only included two Taiwan studies [7, 13] using that database. Eventually, three studies (two studies in Taiwan and one study in India) were included in the meta-analysis (Fig. 2) considering sample sizes and study population. Despite substantial heterogeneity between studies, the pooled analysis (see Fig. 2) and the six individuals suggested metformin usage could decrease the risk of TB among diabetics (OR, 0.38; 95%CI, 0.21 to 0.66). However, the meta-analysis (see Fig. 2) exploring the potential risk of LTBI in patients with DM reported that metformin prescription was not statistically related with the onset of LTBI (OR, 0.73; 95%CI, 0.30 to 1.79).

The impact of metformin on treatment outcomes of TB disease

According to the combined analyses (see Fig. 3), the TB mortality could be limited by metformin usage (OR, 0.47; 95%CI, 0.27 to 0.83), and the sputum culture conversion at 2 months of TB disease was significantly promoted in metformin users compared to non-users (OR, 2.72; 95%CI, 1.11 to 6.69). Contrarily, the pooled result of the relapse of TB within 3 years was not statistically different (OR, 0.55; 95%CI, 0.04 to 8.25) between the metformin group and the control group.

Discussion

In this comprehensive systematic review from 12 observational studies among diabetics, metformin prescription is significantly associated with a decreased risk of TB disease, a smaller TB mortality, and a higher probability of sputum culture conversion at 2 months. Metformin prescription could not reduce the risk of LTBI and the relapse rate of TB disease. The result supports an auxiliary anti-tuberculosis role of metformin in patients with DM.

Due to the different study design, study population and the definition of outcomes (see Table 3), the meta-analysis on the risk of TB showed substantial heterogeneity (see Fig. 2, I2 = 83.0%, P = 0.003). The diagnostic methods of LTBI (see Table 3) in the study by Singhal et al. [4] (T-SPOT.TB) and Magee et al. [8] (QFT, QuantiFERON-TB Gold In-tube) were both based on T-cell interferon-gamma release assays, however, in distinct approaches. The difference in diagnosis method may lead to obvious between-study heterogeneity (see Fig. 2, I2 = 73.5%, P = 0.052). The analysis of the impact of metformin on the relapse of TB also showed obvious heterogeneity (see Fig. 3, I2 = 74.2%, P = 0.049).

Individual studies [7, 9, 10, 13, 19, 20] and pooled analysis provide sufficient evidence that patients with DM initiating metformin usage have a lower risk of TB disease compared to non-users. However, this phenomenon does not occur in the detection of LTBI. TB is known as a granulomatous inflammatory disease involving a special immunopathology. Most TB infections do not induce symptoms among patients, which is regarded as LTBI, and only a part of them turn into active TB disease in those who have a weakened immune system [22]. Accordingly, metformin could enhance Mtb-specific host immunity [4]. Combining the epidemiological evidence, we speculate that metformin treatment could inhibit the conversion of LTBI to active TB disease. This finding is consistent with previous studies [4, 5, 14] that metformin could only function as a host-directed therapy rather than an Mtb- directed therapy.

Metformin treatment in the course of anti-TB regimen could improve treatment outcomes among patients with both DM and TB. However, metformin prescription could not limit the relapse of TB disease. Recent studies [4, 14, 21] indicate that the anti-tuberculosis effect of metformin is dependent on the standard regimen for TB, and metformin only acts as a supporting role with long-term medication. Two studies [11, 21] suggest that metformin usage could not reduce the sputum culture conversion in patients with DM. We consider the small sample size substantially reduce the statistical power, and the deficiency has been solved by the meta-analysis (see Fig. 3). The impact of metformin on the treatment of TB is inspiring. However, to ensure the therapeutic effect of metformin on TB, well-designed randomized controlled trials are necessary.

The mechanism of how metformin affects the human immune system to Mtb has been explored in biological experiments [4, 14]. Metformin affects immune response and inflammation in multiple approaches. The protecting effect of metformin on TB patients is mediated by increased host cell production of mitochondrial reactive oxygen species and increased acidification of mycobacterial phagosome [4]. Metformin treatment also shows an anti-inflammatory effect through the activation of AMPK, a negative regulator of inflammation process [4]. At the individual level, metformin administered to healthy human beings leads to significant down-regulation of genes functioned in oxidative phosphorylation, mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) signaling and type I interferon response pathways, following stimulation with Mtb [14]. Experimental evidence supports the host-directed effect of metformin on TB disease.

Metformin is used to prevent the onset of DM in high-risk populations [23], while DM increases the risk of TB disease and adverse TB outcomes [24]. Combined with our findings, we suggest that metformin usage may prevent DM and TB at the same time. Moreover, metformin approaches a host-directed therapy for TB, which could (1) amplify the efficacy of antibiotic-based treatment, (2) shorten anti-TB regimens, and (3) promote the development of immunological memory that reduces the relapse of TB [4].

Strengths and limitations

The research was the first systematic review that focused on the association between metformin and TB. We tried to improve the efficiency of meta-analyses by minimizing data duplication and analyzing diverse treatment outcomes of TB. However, due to the limited data from original studies, we failed to conduct meta-regressions, dose-effect analyses and subgroup analyses. This research was based on diabetics, and whether metformin could affect the risk and treatment of TB among people without DM was still unclear. Because the study design and the population varied between included studies, there was substantial heterogeneity in meta-analyses, and the heterogeneity could not be eliminated by the subgroup analysis or sensitivity analysis for the limited data.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this systematic review indicate that usage of metformin could significantly reduce the risk of TB disease among diabetics. Treatment outcomes of TB could be improved by metformin prescription in patients with DM. To confirm therapeutic and preventive effects of metformin on TB, well-designed randomized controlled trials, however, in patients with or without DM, are needed.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data for this study are presented in tables, figures and supplementary materials.

Abbreviations

- AMPK:

-

Adenosine monophosphate-activated protein kinase

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- DM:

-

Diabetes mellitus

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- LTBI:

-

Latent tuberculosis infection

- Mtb :

-

Mycobacterium tuberculosis

- mTOR:

-

Mammalian target of rapamycin

- NOS:

-

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale

- OR:

-

Odds ratio

- PECO:

-

Population, exposure, comparator, and outcome

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RR:

-

Relative risk

- TB:

-

Tuberculosis

References

Furin J, Cox H, Pai M. Tuberculosis. Lancet (London, England). 2019;393(10181):1642–56.

WHO. Global tuberculosis report 2018. Sept 18, 2018. https://www.who.int/tb/publications/global_report/en/. (Accessed 20 Mar 2019).

Padmapriyadarsini C, Bhavani PK, Natrajan M, Ponnuraja C, Kumar H, Gomathy SN, et al. Evaluation of metformin in combination with rifampicin containing antituberculosis therapy in patients with new, smear-positive pulmonary tuberculosis (METRIF): study protocol for a randomised clinical trial. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3):e024363.

Singhal A, Jie L, Kumar P, Hong GS, Leow MKS, Paleja B, et al. Metformin as adjunct antituberculosis therapy. Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(263no pagination):263ra159.

Vashisht R, Brahmachari SK. Metformin as a potential combination therapy with existing front-line antibiotics for tuberculosis. J Transl Med. 2015;13:83.

Malik F, Mehdi SF, Ali H, Patel P, Basharat A, Kumar A, et al. Is metformin poised for a second career as an antimicrobial? Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2018;34(4):e2975.

Tseng CH. Metformin Decreases Risk of Tuberculosis Infection in Type 2 Diabetes Patients. J Clin Med. 2018;7(9):264.

Magee MJ, Salindri AD, Kornfeld H, Singhal A. Reduced prevalence of latent tuberculosis infection in diabetes patients using metformin and statins. Eur Respir J. 2019;53(3):1801695.

Lee MC, Chiang CY, Lee CH, Ho CM, Chang CH, Wang JY, et al. Metformin use is associated with a low risk of tuberculosis among newly diagnosed diabetes mellitus patients with normal renal function: a nationwide cohort study with validated diagnostic criteria. PLoS One. 2018;13(10):e0205807.

Lin SY, Tu HP, Lu PL, Chen TC, Wang WH, Chong IW, et al. Metformin is associated with a lower risk of active tuberculosis in patients with type 2 diabetes. Respirology (Carlton, Vic). 2018;23(11):1063–73.

Lee YJ, Han SK, Park JH, Lee JK, Kim DK, Chung HS, Heo EY. The effect of metformin on culture conversion in tuberculosis patients with diabetes mellitus. Korean J Intern Med. 2018;33(5):933–40.

Degner NR, Wang JY, Golub JE, Karakousis PC. Metformin use reverses the increased mortality associated with diabetes mellitus during tuberculosis treatment. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;66(2):198–205.

Pan SW, Yen YF, Kou YR, Chuang PH, Su VYF, Feng JY, et al. The risk of TB in patients with type 2 diabetes initiating metformin vs sulfonylurea treatment. Chest. 2018;153(6):1347–57.

Lachmandas E, Eckold C, Bohme J, Koeken V, Marzuki MB, Blok B et al. Metformin Alters Human Host Responses to Mycobacterium tuberculosis in Healthy Subjects. J Infect Dis. 2019;220(1):139–50.

Fralick M, Sy E, Hassan A, Burke MJ, Mostofsky E, Karsies T. Association of Concussion With the Risk of Suicide: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(2):144–51.

Kivimaki M, Jokela M, Nyberg ST, Singh-Manoux A, Fransson EI, Alfredsson L, et al. Long working hours and risk of coronary heart disease and stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis of published and unpublished data for 603,838 individuals. Lancet (London, England). 2015;386(10005):1739–46.

Yu X, Jiang D, Wang J, Wang R, Chen T, Wang K et al. Metformin prescription and aortic aneurysm: systematic review and meta-analysis. Heart (British Cardiac Society). 2019;105(17):1351–7.

Leow MK, Dalan R, Chee CB, Earnest A, Chew DE, Tan AW, et al. Latent tuberculosis in patients with diabetes mellitus: prevalence, progression and public health implications. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2014;122(9):528–32.

Marupuru S, Senapati P, Sekhar MS. Protective effect of metformin against tuberculosis in diabetic patients. Value Health. 2016;19(7):A895.

Lin HF, Liao KF, Chang CM, Lai SW, Tsai PY, Sung FC. Anti-diabetic medication reduces risk of pulmonary tuberculosis in diabetic patients: a population-based cohort study in Taiwan. Kuwait Med J. 2017;49(1):22–8.

Dey A, Playford MP, Joshi AA, Belur AD, Goyal A, Elnabawi YA, et al. Improvement in large density hdl particle number by NMR is associated with improvement in vascular inflammation by 18-FDG PET/CT at one-year in psoriasis. J Investig Med. 2018;66(3):701.

Escalante P. In the clinic. Tuberculosis. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(11):ITC61–614 quiz ITV616.

Metformin for Prediabetes. JAMA. 2017;317(11):1171. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2016.17844.

Baker MA, Harries AD, Jeon CY, Hart JE, Kapur A, Lonnroth K, et al. The impact of diabetes on tuberculosis treatment outcomes: a systematic review. BMC Med. 2011;9:81.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank all the authors of the original articles.

Funding

This review was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (NSFC,71603091). The funder did not participate in study design, data collection, data analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

XY, LL, SC and XW conceived the idea. XY and LX conducted the literature research. XY and LL screened and identified eligible articles. XF and FC conducted the quality evaluation of the included studies. XY and LL extracted the data and did the synthesis and analysis. The manuscript was completed with the participation of all authors, and all authors approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was not necessary for this systematic review.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

PRISMA checklist.

Additional file 2.

Search Strategy.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, X., Li, L., Xia, L. et al. Impact of metformin on the risk and treatment outcomes of tuberculosis in diabetics: a systematic review. BMC Infect Dis 19, 859 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4548-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4548-4