Abstract

Background

Pulmonary Cryptococcosis (PC) is diagnosed with increasing incidence in recent years, but it does not commonly involve the pleural space. Here, we report a HIV-negative case with advanced stage IIIB non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with radiation therapy presented with dyspnea, a new PET-positive lung mass and bilateral pleural effusion suspecting progressive cancer. However, the patient has been diagnosed as pulmonary cryptococcal infection and successfully treated with oral fluconazole therapy.

Case presentation

A 77-year-old male with advanced stage non-small cell lung cancer treated with combined chemo-radiation therapy who presented with progressive dyspnea, a new PET-positive left lower lobe lung mass and bilateral pleural effusions. Initial diagnostic thoracentesis and bronchoscopy yielded no cancer, but instead found yeast forms consistent with cryptococcal organisms in the transbronchial biopsies of the left lower lobe lung mass. Subsequent to this, the previously collected pleural fluid culture showed growth of Cryptococcus neoformans. The same sample of pleural effusion was tested and was found to be positive for crytococcal antigen (CrAg) by a lateral flow assay (LFA). The patient has been treated with oral fluconazole therapy resulting in gradual resolution of the nodular infiltrates.

Conclusion

PC should be considered in immunosuppressed cancer patients. Additionally, concomitant pleural involvement in pulmonary cryptococcal infections may occur. The incidence of false positive 18FDG-PET scans in granulomatous infections and the use of CrAg testing in pleural fluid to aid in diagnosis are reviewed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pulmonary cryptococcosis (PC) is diagnosed with increasing incidence in recent years in both immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients, but it does not commonly involve the pleural space. The worldwide incidence of pulmonary cryptococcal infection has been increasing over the past decades in both HIV infected and in non-HIV patients [1,2,3,4]. Although PC occurs in immunocompetent hosts, the increase in hematologic stem-cell and solid organ transplant patients, the expanded use of immunosuppressive drugs in inflammatory disorders, and cytotoxic chemo-radiation therapies in cancer patients have increased its prevalence.

Here, we report a HIV-negative case with advanced stage IIIB non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) treated with radiation therapy presented with dyspnea, a new PET-positive lung mass and bilateral pleural effusion suggestive of progressive cancer. However, the patient has been diagnosed as PC and was successfully treated with oral fluconazole therapy.

Case presentation

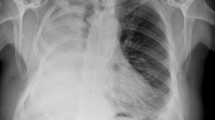

A 77-year-old Chinese American male with stage IIIB (T4N2M0) NSCLC was referred for evaluation and management of progressive dyspnea in March. His past medical history included a 120 pack years smoking history and severe underlying chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Four months prior to this presentation, he developed non-anginal anterior chest pain. A large 6 cm × 9 cm lung mass invading through the left anterior chest wall into ribs and manubrium was biopsied and found to be a squamous cell cancer (Fig. 1a). The patient underwent definitive radiation therapy with a good local response, but he had poor systemic tolerance to one course of the chemotherapy given post radiation. Even though he had severe COPD and pre-existing severe diffuse atherosclerotic vascular disease (coronary artery disease, status post coronary artery bypass, bilateral carotid endarterectomies, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and hyperlipidemia), he neither had any significant exertional dyspnea nor history of congestive heart failure prior to the cancer diagnosis and initiation of cancer therapy. A follow-up CT scan was performed in March (Fig. 1b). At the time of his progressive dyspnea, shrinkage of the left chest wall mass and left upper lobe infiltrates was demonstrated, but appearence of a new 3.9 cm × 4 cm left lower lobe (LLL) mass outside the previous radiation portal and new bilateral pleural effusions were observed. 18FDG-PET scan (Fig. 1c) showed intense uptake (SUVmax 9.9) fusing to the new LLL mass, while the original left upper chest wall tumor site only revealed moderate uptake of SUV 2.6 consistent with post treatment changes.

a1-a3: Baseline CT images of the left upper chest wall tumor, a large 6 cm × 9 cm LUL mass invading through the left anterior chest wall into ribs as (four months prior to pleural effusion); b1-b3: Response in the left upper lobe chest wall mass, but appearance of a new LLL nodular mass as well as pleural effusion (March); c1-c2:18FDG-PET image demonstrated intense FDG activity fusing to 3.3 × 4 cm left lower lobe mass with SUV max 9.9, but minimal left upper lobe chest wall uptake (March); d1-d3:Chest CT scan post-fluconazole therapy (five months post-fluconazole therapy) showed that Left lower lobe mass has significantly diminished in size. Right pleural effusion had resolved; e1-e2: 18FDG-PET image follow-up post PC therapy shows resolution of LLL uptake, with some minimal chest-wall uptake (eight months post-fluconazole therapy)

On review of systems, the patient denied angina, orthopnea nor paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea that helped to rule out congestive heart failure. He had a non-productive cough and didn’t have hemoptysis. He also denied fever, chills or night sweats. Physical examination revealed dullness to percussion at the lung bases, consistent with bilateral pleural fluid. He had trace lower extremity edema. Other pertinent studies included a cardiac echocardiogram from two months prior, when the patient had a left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 45–50%, and trace tricuspid regurgitation with an estimated right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) of 50 mmHg.

Left sided thoracentesis was performed twice for diagnostic purposes. The first tap removed 1000 ml of orange-red sero-sanguinous fluid, that on chemical analysis suggested a transudate as the pleural protein was only 3.0 with a serum protein of 6.2 g / dl (ratio < 0.5) and the pleural LDH of 122 is also < 0.6 of the serum LDH. The pH was 7.40 and pleural glucose was 104. Bacterial culture was negative and cytology revealed reactive mesothelial cell, histiocytes and lymphocytes. The pleural fluid cell count revealed a lymphocytosis of 596 /cu mm, neutrophils of 308 / cu mm while the peripheral WBC of 8370 / cu mm showed a lymphopenia with absolute lymphocyte count of 320 / cu mm. The fluid rapidly re-accumulated and on March 30th, only 18 days later, another 1400 cm3 of hemorrhagic effusions was removed but this time the chemistry was consistent with exudate with a pleural protein of 3.6 g/dl. Initial cultures for bacteria, fungi and mycobacterium were negative. Repeat cytology revealed reactive mesothelial cells, histiocytes, lymphocytes and blood without malignant cells.

Due to the continued lack of a treatable diagnosis, diagnostic bronchoscopy was performed on April 6th. Endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) guided transbronchial needle sampling of regional lymph nodes and the LLL mass were negative for the tumor. However, transbronchial forceps biopsy of the LLL mass showed granulomatous pneumonitis with fungal elements consistent with capsule deficient Cryptococcus on H&E and gomori methenamine silver stain (Fig. 2). Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) sent for pan-culture did not grow any pathogens, and the BAL galactomannan was negative at 0.36 (cutoff < 0.50). Subsequently, the pleural fluid collected on March 30th grew Cryptococcus neoformans after 10 days of culture.

The patient’s pulmonary cryptococcal infection with pleural involvement was probably attributed to his cancer and the treatment. His HIV test was negative. A serum Cryptococcal antigen (CrAg) was negative. He did not have neurologic symptoms, and a baseline MRI of the brain done at the time of initial cancer diagnosis was negative except for findings suggestive of chronic small vessel ischemic disease. Because pleural involvement was considered extrapulmonary spread of the infection, and his present CD4 lymphopenia was an ongoing risk for dissemination, he underwent a lumbar puncture with negative cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) findings (including negative CSF CrAg). Serum galactomannan level was negative at 0.08. Upon retrospective review, the patient had a baseline lymphopenia of 950 / cu mm prior to the initial radiation and chemotherapy. The lymphopenia had never recovered with absolute lymphocyte counts (ALC) between 400 and 600 / cu mm. A T-cell subset checked at the time of the first thoracentesis revealed a CD 4+ cell percent of 24.3% (normal range 32–68%) and absolute CD4+ count of 112/cu mm (normal range 458–1344 /cu mm). Pleural fluid collected from the first thoracentesis on March 12th was analyzed for the presence of CrAg. It was negative by enzyme-linked immunosorbentassays (ELISA), but was positive by lateral flow assay (LFA).

Fluconazole therapy, dose adjusted for renal dysfunction at 400 mg PO q24 was started on April 9th. Subsequent follow-up for 10 months after initiation of the treatment showed progressive clinical improvements with resolution of dyspnea, cough, recovery of appetite and radiographic improvement in chest imaging (Fig. 1d and e). He finally came to us in April of 2015 for a checkup of his supraclavicular lymphadenopathy and chest CT scan showing new nodules of bilateral lungs in April of 2015. We performed fine needle aspiration and the reports showed malignancy. Hence, the patient refused to undergo further management and he passed away that year after six months.

Discussion and conclusions

This case is noteworthy for the following: (1) Uncommon but possibly under-recognized pleural involvement in PC infections; (2) testing of pleural fluid for CrAg; (3) Nonspecific 18 FDG uptake in PET imaging caused by unsuspected opportunistic infections or other inflammatory conditions that can lead to false positive misdiagnosis of lung cancer dissemination.

The radiologic presentation of PC varies with patterns dependent upon host immune function. Immunocompetent patients generally present radiographically with single nodule, or sometimes multiple nodules. On the other hand, in immunocompromised cases, pneumonic or mixed nodular-pneumonic patterns, or cavitatary lesions combined with pulmonary infiltrates are more common [5,6,7]. Pleural effusions although reported, are uncommon in PC cases [7,8,9,10,11,12]. Pleural effusions due to Cryptococcus neoformans infection were first reported in the English literature in 1941 [8], with sporadic cases reported [9,10,11] until 1980 when Young and co-workers presented only 2 of their own cases but they were reviewed together with 28 cases previously reported in the literature [12]. In our recent report of 76 Chinese patients with PC [7], only 5 cases (6.58%, 5/76) had associated pleural effusion, almost equally divided between immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients (2 vs. 3, respectively).

In addition, our patient developed a new PET-positive focal lung mass with intense 18FDG uptake (SUV max 9.9) that is also consistent with metastatic disease. Because 18FDG is a non-specific tumor-imaging agent, 18FDG -PET scans performed for the evaluation of focal lung lesions suspicious for malignancies will yield false positive results in a number of granulomatous infectious and inflammatory conditions due to non-specific glucose uptake. The specificity of a “positive” scan for malignancy is lowered from mid-80% to 40–60% range in regions of endemic granulomatous fungal and mycobacterial infections [13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20]. Specifically in PC, in our review of 76 patients with pathologically proven PC [7], the initial clinical misdiagnosis rate for lung cancer was 30.26% (23/76), and this was largely attributable to a high 18FDG uptake. 46 of the 76 cases with focal PC had a 18F-FDG-PET scan, and 60.87% (28/46) showed high degree of abnormal uptake in the lung lesions (SUV > 2.5), which typically indicates malignancy. Therefore, we would like to highlight that although 18F-FDG-PET has a good sensitivity in identifying metabolically active thoracic malignancies, it may be falsely positive secondary to granulomatous disease. Findings of unclear significance on PET after cytotoxic therapy underscore the importance of confirmatory tissue biopsy. In this case the combination of histologic findings, special stains, and the ultimate proof of a positive fungal culture from the pleural fluid provided a diagnosis and allowed initiation of optimal therapy.

A positive fungal culture also plays a key role in the management of PC cases. According to the review of PC cases with pleural effusions, cultures of pleural effusion for Cryptococcus were positive in 42.31% (11/26) of cases in which this were recorded [12]. Our present case also showed positive Cryptococcal neoformans culture, and interestingly only of pleural effusion but not of the BAL fluid. It is now thought that Cryptococcal neoformans is the most common risk for cryptococcosis in immunocompromised patients especially acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), whereas infections caused by C. gattii are more often reported in immunocompetent patients with undefined risk than in the immunocompromised.

Based on clinical guidelines, oral fluconazole therapy (400 mg, 6–12 months) was recommended for non-meningeal cryptococcosis in immunosupressed patients with mild-moderate symptoms patients. Previous studies also reported that the outcome of PC is often better in localized diseases than that of disseminated diseases [12].

In addition to fungal culture, the cryptococcus antigen (CrAg) test is considered an effective non-invasive diagnostic tool of PC [21]. The role of CrAg test in serum and CSF is well accepted [21, 22]. In literature review, the sensitivity / specificities for CrAg is as high as 98%/98% in serum, and 100%/99% in CSF [21]. As for testing CrAg in pleural effusion, apart from our case, there were 9 published cases in which CrAg test was recorded in the English literature since 1978 [11, 12, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29] As listed in Table 1 [30,31,32], 8 of the 10 cases (80) % showed positive CrAg in the pleural fluid. 6 out of 10 showed positive pleural PC culture. Two cases [11, 29] that were negative for pleural fluid CrAg were also negative for culture. Two cases [25, 27] were negative by culture but positive for CrAg. Positive pleural fluid CrAg per-se does not predict a worse prognosis (5/8 PE CrAg positive cases that were also culture positive were localized), however when there is a discordance of positive results, specifically when the pleural CrAg was positive but the pleural fluid culture was negative, the two cases were disseminated. The significance of this observation is unclear in a small collection of case reports, and more studies are needed to determine whether finding an antigen in dispersed sources in the absence of culture positivity could portend dissemination. The newly released CrAg test method of lateral flow assay (LFA) has been found to be more sensitive (unpublished data) and requires minimal laboratory infrastructure [30]. In our case, pleural fluid was tested for CrAg by two methods, the ELISA test was negative, but the LFA test was positive. Recent study targeting HIV+ patients with CrAg screening and pre-emptive fluconazole therapy in have demonstrated cost-saving to the health care systems, hence its integration into routine HIV care for persons with CD4 < 100 cells per microliter is recommended [30]. Our patient does not have HIV, but did have baseline deficits in his cell-mediated immunity with lymphopenia and a low CD4 count. The findings in our case and in the literature suggests that an opportunistic infection due to atypical non-pyogenic infections, including PC should be considered in patients with serious underlying diseases compromising the subject’s immune function. Future studies are needed to evaluate CrAg screening in non-HIV but at-risk patients and a sensitive CrAg test may be included in the evaluation of idiopathic pleural effusions in such cases. Our patient had lung histology consistent with PC, and yet BAL culture was negative for fungi. Whether there is a role of CrAg testing for BAL and by which technique it can be done is another topic for further investigation.

Pleural involvement by pulmonary cryptococcal infections is under-appreciated, and can occur in non-HIV patients who are not manifesting typical signs of an infection. In patients with underlying malignancies with findings on imaging suggestive of recurrent or progressive disease, abnormal 18FDG-PET uptake findings require confirmatory tissue biopsy and culture. When biopsy results are non-specific, additional studies for invasive granulomatous infections, including pulmonary cryptococcosis should be considered. Where indicated, evaluation of pleural effusion should include sending specimen for a sensitive CrAg assay and for fungal culture. Prompt diagnosis and guidelines-directed therapy will improve outcomes in patients who may otherwise have stable underlying cancer, but may succumb to infectious complications.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable (no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study).

Abbreviations

- AIDS:

-

Acquired immune deficiency syndrome

- BAL:

-

Bronchoalveolar lavage

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CrAg:

-

Crytococcal antigen

- CSF:

-

Cerebrospinal fluid

- EBUS:

-

Endobronchial ultrasound

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbentassays

- LFA:

-

Lateral flow assay

- LLL:

-

Left lower lobe

- LVEF:

-

Left ventricular ejection fraction

- PC:

-

Pulmonary Cryptococcosis NSCLC: Non-small cell lung cancer

- RVSP:

-

Right ventricular systolic pressure

References

Perfect JR, Dismukes WE, Dromer F, Goldman DL, Graybill JR, Hamill RJ, Harrison TS, Larsen RA, Lortholary O, Nguyen MH, Pappas PG, Powderly WG, Singh N, Sobel JD, Sorrell TC. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of cryptococcal disease: 2010 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:291–322.

Galanis E, Macdougall L. Epidemiology of Cryptococcus gattii, British Columbia, Canada, 1999-2007. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:251–7.

Vilchez RA, Irish W, Lacomis J, Costello P, Fung J, Kusne S. The clinical epidemiology of pulmonary cryptococcosis in non-AIDS patients at a tertiary care medical center. Medicine. 2001;80:308–12.

Kontoyiannis DP, Peitsch WK, Reddy BT, Whimbey EE, Han XY, Bodey GP, Rolston KV. Cryptococcosis in patients with cancer. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:E145–50.

Chang WC, Tzao C, Hsu HH, Lee SC, Huang KL, Tung HJ, Chen CY. Pulmonary cryptococcosis: comparison of clinical and radiographic characteristics in immunocompetent and immunocompromised patients. Chest. 2006;129:333–40.

Lindell RM, Hartman TE, Nadrous HF, Ryu JH. Pulmonary cryptococcosis: CT findings in immunocompetent patients. Radiology. 2005;236:326–31.

Zhang Y, Li N, Zhang Y, Li H, Chen X, Wang S, Zhang X, Zhang R, Xu J, Shi J, Yung RC. Clinical analysis of 76 patients pathologically diagnosed with pulmonary cryptococcosis. Eur Respir J. 2012;40:1191–200.

Reeves DL, Butt EM, Hammack RW. Torula infection of the lungs and central nervous system: reports of six cases with three autopsies. Arch Intern Med. 1941;68:57–79.

Epstein R, Cole R, Hunt KK Jr. Pleural effusion secondary to pulmonary cryptococcosis. Chest. 1972;61:296–8.

Smilack JD, Bellet RE, Talman WT Jr. Cryptococcal pleural effusion. JAMA. 1975;232:639–41.

Gross PA, Patel C, Spitler LE. Disseminated Cryptococcus treated with transfer factor. JAMA. 1978;240:2460–2.

Young EJ, Hirsh DD, Fainstein V, Williams TW. Pleural effusions due to Cryptococcus neoformans: a review of the literature and report of two cases with cryptococcal antigen determinations. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1980;121:743–7.

Huang CJ, You DL, Lee PI, Hsu LH, Liu CC, Shih CS, Shih CC, Tseng HC. Characteristics of integrated 18F-FDG PET/CT in Pulmonary Cryptococcosis. Acta Radiol. 2009;50:374–8.

Song KD, Lee KS, Chung MP, Kwon OJ, Kim TS, Yi CA, Chung MJ. Pulmonary cryptococcosis: imaging findings in 23 non-AIDS patients. Korean J Radiol. 2010;11:407–16.

Igai H, Gotoh M, Yokomise H. Computed tomography (CT) and positron emission tomography with [18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG-PET) images of pulmonary cryptococcosis mimicking lung cancer. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2006;30:837–9.

Ghimire P, Sah AK. Pulmonary cryptococcosis and tuberculoma mimicking primary and metastatic lung cancer in 18F-FDG PET/CT. Nepal Med Coll J. 2011;13:142–3.

Hsu CH, Lee CM, Wang FC, Lin YH. F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in pulmonary cryptococcoma. Clin Nucl Med. 2003;28:791–3.

Deppen S, Putnam JB Jr, Andrade G, Speroff T, Nesbitt JC, Lambright ES, Massion PP, Walker R, Grogan EL. Accuracy of FDG-PET to diagnose lung cancer in a region of endemic granulomatous disease. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;92:428–32 discussion 433.

Chang JM, Lee HJ, Goo JM, Lee HY, Lee JJ, Chung JK, Im JG. False positive and false negative FDG-PET scans in various thoracic diseases. Korean J Radiol. 2006;7:57–69.

Tian J, Yang X, Yu L, Chen P, Xin J, Ma L, Feng H, Tan Y, Zhao Z, Wu W. A multicenter clinical trial on the diagnostic value of dual-tracer PET/CT in pulmonary lesions using 3′-deoxy-3′-18F-fluorothymidine and 18F-FDG. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:186–94.

Frank UK, Nishimura SL, Li NC, Sugai K, Yajko DM, Hadley WK, Ng VL. Evaluation of an enzyme immunoassay for detection of cryptococcal capsular polysaccharide antigen in serum and cerebrospinal fluid. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:97–101.

Lindsley MD, Mekha N, Baggett HC, Surinthong Y, Autthateinchai R, Sawatwong P, Harris JR, Park BJ, Chiller T, Balajee SA, Poonwan N. Evaluation of a newly developed lateral flow immunoassay for the diagnosis of cryptococcosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;53:321–5.

Conces DJ Jr, Vix VA, Tarver RD. Pleural cryptococcosis. J Thorac Imaging. 1990;5:84–6.

Fukuchi M, Mizushima Y, Hori T, Kobayashi M. Cryptococcal pleural effusion in a patient with chronic renal failure receiving long-term corticosteroid therapy for rheumatoid arthritis. Intern Med. 1998;37:534–7.

Wong CM, Lim KH, Liam CK. Massive pleural effusions in cryptococcal meningitis. Postgrad Med J. 1999;75:297–8.

Jain N, Duggal L, Malhotra S, Sharma A, Garg A. Pleural cryptococcosis in AIDS-Unusual presentation. Respir Med Extra. 2007;3:108–10.

Kamiya H, Ishikawa R, Moriya A, Arai A, Morimoto K, Ando T, Ikushima S, Oritsu M, Takemura T. Disseminated Cryptococcosis complicated with bilateral pleural effusion and ascites during corticosteroid therapy for organizing pneumonia with myelodysplastic syndrome. Intern Med. 2008;47:1981–6.

Cartwright E, Rouphael N, Jain S, Ilksoy N. Pleural effusion in a patient with AIDS. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1887–8 1926-7.

Kamminga SK, Boer C, Rijkeboer AA, Paul MA, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Strack van Schijndel RJ. Occult pleural cryptococcosis in an immunocompromised patient. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35:961–2.

Rajasingham R, Meya DB, Boulware DR. Integrating cryptococcal antigen screening and pre-emptive treatment into routine HIV care. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2012;59:e85–91.

Chen M, Wang X, Yu X, et al. Pleural effusion as the initial clinical presentation in disseminated cryptococcosis and fungaemia: an unusual manifestation and a literature review. BMC Infect Dis. 2015 Sep 22;15:385.

Kushima Y, Takizawa H, Machida Y, et al. Cryptococcal Pleuritis presenting with lymphocyte-predominant and high levels of adenosine deaminase in pleural effusions coincident with pulmonary tuberculosis. Intern Med. 2018 Jan 1;57(1):115–20.

Acknowledgements

We thank all of authors work and our patient’s cooperation.

Funding

This study thanks for the grant’s support in interpretation of data and in writing the manuscript (the National Science Foundation of China No: 81500052).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YZ, HL and RCY were responsible for literature review and finalized the manuscript. SZ and ADT participated in the pathologic analysis. JT, JB, RH and SB participated in patient care and cure. MZ and HL were involved in data collection and clinical follow-up. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethic approval was obtained from the local ethics committee, and written consent to participate was obtained from the patient.

Consent for publication

Written consent to publish this case report was obtained from the patient.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Zhang, S.X., Trivedi, J. et al. Pleural fluid secondary to pulmonary cryptococcal infection: a case report and review of the literature. BMC Infect Dis 19, 710 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4343-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4343-2