Abstract

Background

Lyme borreliosis (LB) is a tick-borne disease caused by spirochetes belonging to the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato species. Due to a variety of clinical manifestations, diagnosing LB can be challenging, and laboratory work-up is usually required in case of disseminated LB. However, the current standard of diagnostics is serology, which comes with several shortcomings. Antibody formation may be absent in the early phase of the disease, and once IgG-seroconversion has occurred, it can be difficult to distinguish between a past (cured or self-cleared) LB and an active infection. It has been postulated that novel cellular tests for LB may have both higher sensitivity earlier in the course of the disease, and may be able to discriminate between a past and active infection.

Methods

VICTORY is a prospective two-gate case-control study. We strive to include 150 patients who meet the European case definitions for either localized or disseminated LB. In addition, we aim to include 225 healthy controls without current LB and 60 controls with potentially cross-reactive conditions. We will perform four different cellular tests in all of these participants, which will allow us to determine sensitivity and specificity. In LB patients, we will repeat cellular tests at 6 weeks and 12 weeks after start of antibiotic treatment to assess the usefulness as ‘test-of-cure’. Furthermore, we will investigate the performance of the different cellular tests in a cohort of patients with persistent symptoms attributed to LB.

Discussion

This article describes the background and design of the VICTORY study protocol. The findings of our study will help to better appreciate the utility of cellular tests in the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis.

Trial registration

NL7732 (Netherlands Trial Register, trialregister.nl).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

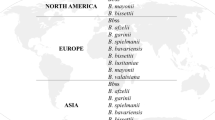

Lyme borreliosis (LB) is a widely prevalent infectious disease in the Northern Hemisphere with potentially major health consequences [1, 2]. The causative agent of LB is one of several species of bacteria from the Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato complex, which require the tick as a vector for transmission. LB can be arbitrarily divided into early localized, early disseminated and late (disseminated) manifestations [3]. Common manifestations in Europe include erythema migrans (EM), Lyme neuroborreliosis (LNB), Lyme arthritis and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (ACA) [4, 5].

The diagnosis of LB is primarily based on clinical features, usually combined with serological testing or, when indicated, direct detection of the pathogen in specific bodily materials. As holds true for many serological tests for infectious diseases, Borrelia serology comes with several shortcomings. Sensitivity and specificity depend on several factors, which include the disease duration and type of manifestation. Moreover, an inherent issue with serological testing is the fact that antibody formation takes time and can be aborted after antibiotic treatment [6, 7]. A recent review by Leeflang and colleagues found the overall sensitivity of ELISAs and immunoblots used in Europe to be up to 95% for late manifestations, but as low as 50% for early localized disease (EM) [8]. Specificity ranged from 80 to 95% [8]. An additional problem arises once IgG-seroconversion has occurred, since antibodies oftentimes remain present in the blood for many years, even after the infection has long been cured or self-cleared [7, 9, 10]. These test characteristics result in diagnostic dilemmas in several clinical situations for both patients and physicians.

Some LB patients report persistent symptoms, with the exact percentage varying per manifestation and population assessed [11,12,13,14]. These complaints cause a substantial disease burden in the Netherlands [15]. These symptoms may develop after early, disseminated or late manifestations of LB, despite recommended antibiotic treatment. These symptoms, which mainly include fatigue, general malaise, musculoskeletal pain and neurological symptoms, are more likely to occur when there has been a delay in proper antibiotic treatment [16, 17]. For this reason, an early diagnosis of LB has clear treatment benefits. Antibiotic treatment failure, defined as microbiologically confirmed persisting B. burgdorferi s.l. infection, is uncommon, but has been described [18]. Therefore, a discussion may ensue about whether complaints are caused by a persisting infection (requiring antibiotic treatment), if these symptoms are post-infectious or not even related to LB. Serology cannot make this distinction once seroconversion has occurred.

Cellular tests for LB have been proposed as a (partial) solution to some of these dilemmas. These tests utilize the cellular part of the immune system and have been in use for the diagnosis of tuberculosis for several decades [19]. These in vitro assays function by stimulating patient leukocytes with pathogen-specific antigens and measuring the resulting cellular response. Previous studies have examined the diagnostic value of various types of cellular tests for LB and have yielded varying results [20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. A more recent study by Callister and colleagues found that the sensitivity of a cellular assay for LB based on interferon-gamma (IFN-γ) was higher than that of serology in patients with early localized LB (an EM). In addition, the authors showed that the IFN-γ response waned within months after antibiotic treatment [33]. This supports the hypothesis that cellular tests may have a higher sensitivity than serology earlier in the course of disease, and that they may be used a test-of-cure (i.e. positive before treatment and negative after successful treatment). For patients who have long-lasting –sometimes invalidating– complaints that are attributed to LB, a test that better distinguishes between a persistent Borrelia-infection, post-treatment Lyme borreliosis syndrome (PTLBS) or an altogether different condition could be of great benefit, and could thus guide patient management.

The aforementioned studies investigating cellular tests for LB had important shortcomings. They lacked clear case definitions, were performed in only a small number of participants, or they lacked comparisons with adequate control groups. In addition, many of these studies were performed by the developers of the tests, with insufficient safeguards to prevent a potential conflict of interest. Conversely, the present VICTORY study has been designed to assess the diagnostic performance of various cellular tests for LB in well-defined groups of patients with acute LB and controls by means of a two-gate case-control design. Additionally, we will study the utility of these tests in an observational cohort of patients with prolonged symptoms attributed to LB. In this paper, we describe the study protocol in detail.

Methods/design

Study design

This is a multi-center prospective two-gate case-control study with 1 year of follow-up to assess the diagnostic parameters of cellular tests for LB. In addition, an observational prospective cohort is included to investigate the performance of cellular tests in patients with persistent symptoms attributed to LB. This study entails a collaboration between the Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (RIVM, Bilthoven, the Netherlands) and the clinical expert centers for Lyme borreliosis at the Amsterdam UMC (formerly AMC, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), and the Radboud university medical center (Radboudumc, Nijmegen, the Netherlands). The study has been approved by the medical ethics committee (MEC) of the Amsterdam UMC (registered under no. NL63961.018.18), and is conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study population

We will enroll three groups in the case-control study. Cases are 150 adults from the Netherlands with acute confirmed LB, included before or just after start of antibiotic treatment (Table 1). Our study uses well-established case definitions that largely match the European case definitions as described by Stanek and colleagues [3]. LB patients have early localized, early disseminated, or late disseminated LB. We are also recruiting 225 participants from the general population, who have no current complaints of LB. These participants function as healthy controls in the validation study. Healthy controls are matched with cases by age, gender, and – in order to correct for tick bites – by geographical region. We are enrolling a separate control cohort of 60 participants with medical conditions that are potentially cross-reactive with LB in these cellular tests. These medical conditions include other spirochetal infections (leptospirosis, syphilis), infection with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) or cytomegalovirus (CMV), and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Furthermore, the cellular tests are performed in an observational cohort of participants with persistent symptoms attributed to LB. All adult participants visiting the Lyme outpatient clinics of the Amsterdam UMC or Radboudumc are eligible for the observational cohort and participants are included consecutively. Recruitment has started in May 2018.

Recruitment, inclusion and follow-up of participants

The majority of LB cases are recruited as part of the LymeProspect study, which is also a collaborative effort of the RIVM, Amsterdam UMC and Radboudumc (Netherlands Trial Register: NTR4998/NL4744) [34]. Cases with disseminated LB are additionally recruited under the current protocol. The recruitment procedures, and in- and exclusion criteria for cases are identical in both protocols.

Recruitment, inclusion and follow-up of LB cases occur both online and at the LB clinical expert centers (Fig. 1). Most LB cases are recruited through the website Tekenradar.nl. This national and secured online enrollment platform is operated by the RIVM. Patients can visit the website on their own initiative, or after having been referred to it by their general practitioner (GP). Patients thus recruited primarily have an EM as manifestation of LB, but other forms of confirmed LB may be included through Tekenradar.nl as well. Written informed consent is obtained from eligible participants. Importantly, the participant’s medical doctor is consulted to verify the diagnosis after online enrollment. Blood collection can be done locally or in the participating hospitals and is performed at baseline, after 6 weeks and facultatively after 12 weeks. A secondary inclusion route for cases is through the LB clinical expert centers, after evaluation by one of the investigators (Table 2).

Controls are only recruited under the current protocol. Healthy controls are recruited in two ways. Firstly, from the general population, i.e. from a cohort that has previously been recruited to fill out questionnaires as a population control for other LB-related studies. Additionally, we recruit healthy controls through local laboratories, GP’s offices and outpatient clinics. After obtaining written informed consent, blood is drawn only at baseline (Table 3). Next to inclusion through the Amsterdam UMC or Radboudumc, potentially cross-reactive controls are recruited through various medical institutions. Persons with syphilis may also be recruited through the sexually transmitted infections (STI) clinic of the Amsterdam Public Health Service. Persons with an autoimmune disease may be recruited from the Sint Maartenskliniek for rheumatology in Nijmegen. Persons with leptospirosis and an infection with EBV/CMV are only recruited from the Amsterdam UMC or Radboudumc. After obtaining written informed consent, blood is drawn only at baseline (Table 3).

Participants for the observational cohort with persistent symptoms attributed to LB are recruited from the LB clinical expert centers of the Amsterdam UMC or Radboudumc. After obtaining written informed consent, blood is drawn at baseline and after 12 weeks (Table 4).

Epidemiological and clinical measurements

For LB cases and for participants in the observational cohort, standard demographical characteristics, comorbidities and details on previous tick exposure and previous or current episodes of LB are reported at baseline. During follow-up, new tick bites or new episodes of LB are recorded, as well as new non-LB-related medical diagnoses. Photographs of skin manifestations of LB are obtained for blinded evaluation by independent experts. Participants who are included online can upload these pictures themselves. Cases with confirmed LB who have a skin manifestation have the option of giving additional informed consent for skin biopsies to be taken (Table 2). For all controls, standard demographical characteristics, comorbidities and details on any previous episodes of LB are recorded only at baseline (Table 3).

Laboratory measurements

Four cellular tests for LB will be performed: the Spirofind Revised (Oxford Immunotec), the QuantiFERON-LB (QIAGEN Sciences), the Lyme iSpot (Autoimmun Diagnostika / Genome Identication Diagnostics), and the Lymphocyte Transformation Test-Memory Lymphocyte Immunostimulation Assay (LTT-MELISA, InVitaLab). Details of the various cellular tests are provided in the Additional file 1. The B. burgdorferi s.l. C6 ELISA (Oxford Immunotec) is performed as serological test. All positive and indeterminate C6 ELISA results will be confirmed by IgM and IgG immunoblot (Mikrogen), according to guideline recommendations [35]. All samples are processed blinded, i.e. without any markings related to the identity of the participant, type of participant or time point.

Questionnaires

Confirmed LB cases and participants in the observational cohort will also be asked to fill out online questionnaires through Tekenradar.nl. These will be filled out at inclusion, and after 3, 6, 9 and 12 months and cover a wide array of determinants of health, including assessment of symptoms, disabilities, cognitive-behavioral variables, co-morbid disorders and pre-existing symptoms. These questionnaires are validated and have Dutch norm scores, which enables us to use cutoff scores to determine the severity of symptoms. These questionnaires are specified in the Additional file 1.

Outcome measures and data analysis

The primary outcome measures are the diagnostic parameters of the cellular tests in cases versus healthy controls. We will use the manufacturer-prescribed reference values for interpretation (positive, indiscriminate, negative), and perform a receiver operating characteristic (ROC-) analysis to assess potential new cutoffs. From this, we will calculate the diagnostic parameters (sensitivity and specificity) of the studied tests.

Secondary outcome measures are: i) the comparisons of the diagnostic parameters of the various cellular tests, ii) the correlation of cellular tests with serology results, and iii) the effectiveness of the cellular tests as a test-of-cure. The latter outcome is determined by correlating the cellular responses in LB participants over time to various determinants of health during the one-year follow-up period. Finally, we will assess the performance of the cellular tests and clinical outcomes in the observational cohort of patients with persistent symptoms attributed to LB.

Sample size

We consider cellular tests to be an improvement over serology if they increase the sensitivity of laboratory testing for early LB by 20%, with specificity not dropping below 90%. Inclusion of 100 cases would result in a power of 97% (alpha < 0.05) to detect a significant improvement in sensitivity of 20%. Accounting for loss-to-follow-up, and the fact that the improvement in sensitivity may actually be smaller, we have chosen to include 150 cases in our case-control study. This would still yield a power of 85% (alpha < 0.05) to detect an improvement in sensitivity of 10–15%. We will additionally include 225 healthy controls and 60 potentially cross-reactive controls in the case-control study. For the observational cohort of patients with persistent signs and symptoms attributed to LB, we aim to include 150 participants. Details on the power calculations are provided in the Additional file 1.

Discussion

The VICTORY study evaluates the diagnostic parameters of cellular tests for LB and additionally assesses their performance in an observational cohort of patients with persistent symptoms attributed to LB.

Cellular tests for LB may possibly help in clinical decision making for LB-related problems. National and international guidelines dictate that an EM is a clinical diagnosis and that serological tests should not be performed, as the chance of a false-negative result is considerable [3, 35]. However, the skin lesion is frequently atypical, and in approximately 50% of the cases there is no known history of a tick bite [36, 37], which makes the diagnosis considerably more difficult. Furthermore, the clinical spectrum of early LB can be broad, especially in the United States, where subfebrile temperature and other systemic symptoms are more common in early LB [36, 38, 39]. In such situations, a test with a higher sensitivity and specificity early in disease may lead to an earlier diagnosis.

Several studies have reported on the potential of cellular tests for LB. However, these studies have important shortcomings, which have also been discussed by others [40,41,42,43]. Nonetheless, several cellular tests for LB are commercially available in Europe. In the absence of a thorough assessment of the diagnostic parameters of these commercially available tests, clinicians cannot reliably use the test results in their clinical decision making process. The results of any such unvalidated tests do, however, give the patient an expectation of health or illness. This underscores the urgent need for a proper validation study for cellular tests for LB.

Our study is unprecedented compared to other studies on cellular tests for LB, as the patient populations and diagnoses are strictly defined according to consensus criteria, the study includes healthy controls from the general population and potentially cross-reactive controls, and is appropriately powered. Furthermore, a variety of cellular tests will be compared in parallel. Finally, this study has been designed and is currently being performed in direct collaboration with patient representatives taking into account the patients’ perspective.

As there is no universally applicable reference standard for LB, it is challenging to set up a sufficiently powered one-gate cohort study to assess the diagnostic parameters of the cellular tests under study [44]. However, in our study, the strict case definitions and physician confirmation of diagnosis function as a surrogate for this missing reference standard.

In conclusion, the VICTORY study is a hybrid study consisting of a prospective two-gate case-control study to assess the diagnostic parameters of multiple cellular tests for LB, and an observational prospective cohort study to assess their clinical application in an outpatient setting.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- ACA:

-

Acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans

- AMC:

-

Academic Medical Center

- Amsterdam UMC:

-

Amsterdam University Medical Centers

- CBRSQ:

-

Cognitive Behavioural Responses to Symptoms Questionnaire

- CD4:

-

Cluster of differentiation 4

- CFQ:

-

Cognitive failure questionnaire

- CIS:

-

Checklist Individual Strength

- CMV:

-

Cytomegalovirus

- DbpB:

-

Decorin-binding protein B

- EBV:

-

Epstein-Barr virus

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

- ELISPOT:

-

Enzyme-linked immunospot

- EM:

-

Erythema migrans

- GP:

-

General practitioner

- HADS:

-

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- IFA:

-

Immunofluorescence assay

- IFN-γ:

-

Interferon-gamma

- IgG:

-

Immunoglobulin G

- IgM:

-

Immunoglobulin M

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- IPAQ:

-

International Physical Activity Questionnaire

- IPQ:

-

Illness perception questionnaire

- LB:

-

Lyme borreliosis

- LNB:

-

Lyme neuroborreliosis

- LTT-MELISA:

-

Lymphocyte Transformation Test-Memory Lymphocyte Immunostimulation Assay

- MAT:

-

Microscopic agglutination test

- MEC:

-

Medical ethics committee

- NSAID:

-

Non-steroid anti-inflammatory drug

- OspA:

-

Outer-surface protein A

- OspC:

-

Outer-surface protein C

- PBMC:

-

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PCS:

-

Pain Catastrophizing Scale

- PHQ:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire

- POCT:

-

Point-of-care test

- PTLBS:

-

Post-treatment Lyme borreliosis syndrome

- QFN-LB:

-

Quantiferon-Lyme Borreliosis

- RA:

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

- Radboudumc:

-

Radboud university medical center

- RIVM:

-

Dutch National Institute for Public Health and the Environment

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- RPR:

-

Rapid plasma regain

- s.l.:

-

Sensu lato

- SES:

-

Self-Efficacy Scale

- SF-36:

-

SF-36 Health Status Inventory

- SFUs:

-

Spot-forming units

- SI:

-

Stimulation index

- STI:

-

Sexually transmitted infections

- Tic-P:

-

Trimbos/iMTA questionnaire for Costs associated with Psychiatric Illness

- VDRL:

-

Venereal disease research laboratory

References

Hofhuis A, Harms M, Bennema S, van den Wijngaard CC, van Pelt W. Physician reported incidence of early and late Lyme borreliosis. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:161.

Hofhuis A, Harms M, van den Wijngaard C, Sprong H, van Pelt W. Continuing increase of tick bites and Lyme disease between 1994 and 2009. Ticks Tick Borne Dis. 2015;6(1):69–74.

Stanek G, Fingerle V, Hungeld KP, Jaulhac B, Kaiser R, Krause A, Kristoferitsch W, O'Connell S, Ornstein K, Strle F, et al. Lyme borreliosis: clinical case definitions for diagnosis and management in Europe. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2011;17:69–79.

Berglund J, Eitrem R, Ornstein K, Lindberg A, Ringér A, Elmrud H, Carlsson M, Runehagen A, Svanborg C, Norrby R. An epidemiologic study of Lyme disease in southern Sweden. N Engl J Med. 1995;333(20):1319–27.

Huppertz HI, Bohme M, Standaert SM, Karch H, Plotkin SA. Incidence of Lyme borreliosis in the Wurzburg region of Germany. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1999;18(10):697–703.

Hansen K, Asbrink E. Serodiagnosis of erythema migrans and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans by the Borrelia burgdorferi flagellum enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27(3):545–51.

Hammers-Berggen SH, Lebech AM, Karlsson M, Svenungsson B, Hansen K, Stiernstedt G. Serological follow-up after treatment of patients with erythema Migrans and Neuroborreliosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32(6):1519–25.

Leeflang MM, Ang CW, Berkhout J, Bijlmer HA, Van Bortel W, Brandenburg AH, Van Burgel ND, Van Dam AP, Dessau RB, Fingerle V, et al. The diagnostic accuracy of serological tests for Lyme borreliosis in Europe: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:140.

Kalish RA, McHugh G, Granquist J, Shea B, Ruthazer R, Steere AC. Persistence of immunoglobulin M or immunoglobulin G antibody responses to Borrelia burgdorferi 10–20 years after active Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:780–5.

Aguero-Rosenfeld ME, Nowakowski J, Bittker S, Cooper D, Nadelman RB, Wormser GP. Evolution of the serologic response to Borrelia burgdorferi in treated patients with culture-confirmed erythema Migrans. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34(1):1–9.

Cerar D, Cerar T, Ruzic-Sabljic E, Wormser GP, Strle F. Subjective symptoms after treatment of early Lyme disease. Am J Med. 2010;123(1):79–86.

Weitzner E, McKenna D, Nowakowski J, Scavarda C, Dornbush R, Bittker S, Cooper D, Nadelman RB, Visintainer P, Schwartz I, et al. Long-term assessment of post-treatment symptoms in patients with culture-confirmed early Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(12):1800–6.

Eikeland R, Mygland A, Herlofson K, Ljostad U. European neuroborreliosis: quality of life 30 months after treatment. Acta Neurol Scand. 2011;124(5):349–54.

Wormser GP, Weitzner E, McKenna D, Nadelman RB, Scavarda C, Nowakowski J. Long-term assessment of fatigue in patients with culture-confirmed Lyme disease. Am J Med. 2015;128(2):181–4.

van den Wijngaard CC, Hofhuis A, Harms MG, Haagsma JA, Wong A, de Wit GA, Havelaar AH, Lugner AK, Suijkerbuijk AW, van Pelt W. The burden of Lyme borreliosis expressed in disability-adjusted life years. Eur J Pub Health. 2015;25(6):1071–8.

Cairns V, Godwin J. Post-Lyme borreliosis syndrome: a meta-analysis of reported symptoms. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34(6):1340–5.

Shadick NA, Phillips CB, Sangha O, Logigian EL, Kaplan RF, Wright EA, Fossel AH, Fossel K, Berardi V, Lew RA, et al. Musculoskeletal and neurologic outcomes in patients with previously treated Lyme disease. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131(12):919–26.

Stupica D, Lusa L, Cerar T, Ruzic-Sabljic E, Strle F. Comparison of post-Lyme Borreliosis symptoms in erythema migrans patients with positive and negative Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato skin culture. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis (Larchmont, NY). 2011;11(7):883–9.

Lewinsohn DM, Leonard MK, LoBue PA, Cohn DL, Daley CL, Desmond E, Keane J, Lewinsohn DA, Loeffler AM, Mazurek GH, et al. Official American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention clinical practice guidelines: diagnosis of tuberculosis in adults and children. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64(2):e1–e33.

Valentine-Thon E, Ilsemann K, Sandkamp M. A novel lymphocyte transformation test (LTT-MELISA) for Lyme borreliosis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2007;57(1):27–34.

Von Baehr V, Doebis C, Volk H, von Baehr R. The lymphocyte transformation test for Borrelia detects active Lyme Borreliosis and verifies effective antibiotic treatment. Open Neurol J. 2012;6:104–12.

Nordberg M, Forsberg P, Nyman D, Skogman BH, Nyberg C, Ernerudh J, Eliasson I, Ekerfelt C. Can ELISPOT be applied to a clinical setting as a diagnostic utility for Neuroborreliosis? Cells. 2012;1(2):153–67.

Krause A, Brade V, Schoerner C, Solbach W, Kalden JR, Burmester GR: T-cell proliferation induced by Borrelia burgdorferi in patients with Lyme borreliosis. Arthritis Rheum 1991;34(4):393–402.

Jin C, Roen DR, Lehmann PV, Kellermann GH. An enhanced ELISPOT assay for sensitive detection of antigen-specific T cell responses to Borrelia burgdorferi. Cells. 2013;2(3):607–20.

Puri BK, Segal DRM, Monro JA. Diagnostic use of the lymphocyte transformation test-memory lymphocyte immunostimulation assay in confirming active Lyme borreliosis in clinically and serologically ambiguous cases. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7(12):5890–2.

Widhe M, Ekerfelt C, Jarefors S, Skogman BH, Peterson EM, Bergstrom S, Forsberg P, Ernerudh J. T-cell epitope mapping of the Borrelia garinii outer surface protein a in Lyme neuroborreliosis. Scand J Immunol. 2009;70(2):141–8.

Huppertz HI, Mösbauer S, Busch DH, Karch H. Lymphoproliferative responses to Borrelia burgdorferi in the diagnosis of Lyme arthritis in children and adolescents. Eur J Pediatr. 1996;155(4):297–302.

Forsberg P, Ernerudh J, Ekerfelt C, Roberg M, Vrethem M, Bergström S. The outer surface proteins of Lyme disease borrelia spirochetes stimulate T cells to secrete interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma): diagnostic and pathogenic implications. Clin Exp Immunol. 1995;101(3):453–60.

Dressler F, Yoshinari NH, Steere AC. The T-cell proliferative assay in the diagnosis of Lyme disease. Ann Intern Med. 1991;115(7):533–9.

Horowitz HW, Pavia CS, Bittker S, Forseter G, Cooper D, Nadelman RB, Byrne D, Johnson RC, Wormser GP. Sustained cellular immune responses to Borrelia burgdorferi: lack of correlation with clinical presentation and serology. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 1994;1(4):373–8.

Rutkowski S, Busch DH, Huppertz HI. Lymphocyte proliferation assay in response to Borrelia burgdorferi in patients with Lyme arthritis: analysis of lymphocyte subsets. Rheumatol Int. 1997;17:151–8.

Yoshinari NH, Reinhardt BN, Steere AC. T cell responses to polypeptide fractions of Borrelia burgdorferi in patients with Lyme arthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 1991;34(6):707–13.

Callister SM, Jobe DA, Stuparic-Stancic A, Miyamasu M, Boyle J, Dattwyler RJ, Arnaboldi PM. Detection of IFN-gamma secretion by T cells collected before and after successful treatment of early Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(10):1235–41.

Vrijmoeth HD, Ursinus J, Harms MG, Zomer TP, Gauw SA, Tulen AD, Kremer K, Sprong H, Knoop H, Vermeeren YM, et al. Prevalence and determinants of persistent symptoms after treatment for Lyme borreliosis: study protocol for an observational, prospective cohort study (LymeProspect). BMC Infect Dis. 2019;19:324.

Healthcare CIfQo: Dutch guideline for Lyme disease. Available on https://www.rivm.nl/sites/default/files/2018-11/CBO%20richtlijn%20Lymeziekte%20definitief%20juli%202013.pdf. Accessed 24 July 2019.

Strle F, Nelson JA, Ruzic-Sabljic E, Cimperman J, Maraspin V, Lotric-Furlan S, Cheng Y, PM M, Trenholme GM, PR N. European Lyme borreliosis: 231 culture-confirmed cases involving patients with erythema migrans. Clin Infect Dis. 1996;23(1):61–5.

Strle F, Videcnik J, Zorman P, Cimperman J, Lotric-Furlan S, Maraspin V. Clinical and epidemiological findings for patients with erythema migrans. Comparison of cohorts from the years 1993 and 2000. Wien Klin Wochenschr. 2002;114(13–14):493–7.

Nadelman R, Nowakowski J, Forseter G, et al. The clinical spectrum of early Lyme borreliosis in patients with culture-confirmed erythema migrans. Am J Med. 1996;100(5):502–8.

Strle F, Nadelman RB, Cimperman J, Nowakowski J, Picken RN, Schwartz I, Maraspin V, Aguero-Rosenfeld ME, Varde S, Lotric-Furlan S, et al. Comparison of culture-confirmed erythema migrans caused by Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto in New York state and by Borrelia afzelii in Slovenia. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130(1):32–6.

Dessau RB, Fingerle V, Gray J, Hunfeld KP, Jaulhac B, Kahl O, Kristoferitsch W, Stanek G, Strle F. The lymphocyte transformation test for the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis has currently not been shown to be clinically useful. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(10):O786–7.

von Baehr V. The lymphocyte transformation test for the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis could fill a gap in the difficult diagnostics of borreliosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20(12):O1155–6.

von Baehr V. The lymphocyte transformation test for the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(3):e22.

Dessau RB, Fingerle V, Gray J, Hunfeld KP, Jaulhac B, Kristoferitsch W, Stanek G, Strle F. The authors reply to comments on "the lymphocyte transformation test for the diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis has currently not been shown to be clinically useful." Clin Microbiol infect 2014;20:O786-O787. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015;21(3):e21.

Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, Vandenbroucke JP, Glas AS, Bossuyt PM. Case-control and two-gate designs in diagnostic accuracy studies. Clin Chem. 2005;51(8):1335–41.

Acknowledgements

First and foremost, the authors acknowledge the patient representatives associated with this project, Els Duba, Kees Niks, Gert van Dijk and Koen van Kempen, who were selected in consultation with the two major Dutch patient organizations for Lyme borreliosis. Their assistance in setting up this study, in acquiring funding, and their continued perspectives during its execution have been invaluable. We thank them for functioning as a sounding board for all researchers involved. The authors additionally acknowledge the following colleagues for their valuable assistance in setting up and performing this study: Hein Sprong, PhD; Kristin Kremer, PhD; Anna Tulen; Ingrid Friesema, PhD; Margriet Harms (all RIVM); J.I. (Jasmin) Ersöz, BASc; Jeanine Ursinus, MD; Dieuwertje Hoornstra, MD; prof. J.A. (Hans) Knoop, PhD; M.M.G. (Mariska) Leeflang, PhD (all AMC); Michelle Brouwer, MSc; H.J.M. (Hadewych) ter Hofstede, MD, PhD; H.D. (Hedwig) Vrijmoeth, MD; F.J. (Fidel) Vos, MD, PhD (all Radboudumc); Tizza Zomer, PhD; Yolande Vermeeren, MD; Barend van Kooten, MD (all Gelre ziekenhuizen).

Sponsor

Amsterdam UMC, location AMC.

Meibergdreef 9, 1105 AZ, Amsterdam, the Netherlands.

Contact/corresponding author: prof. J.W.R. Hovius, MD, PhD (email: victory@amc.uva.nl).

Trial status

Protocol version 1: 24-04-2018.

Protocol version 2: 20-09-2018.

Protocol version 3: 14-03-2019.

Recruitment started: 14-05-2018.

Funding

This study is funded by the Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (ZonMw, project number 522050001), which has peer-reviewed the grant application. It was co-funded by the Ministry of Health of the Netherlands and was additionally made possible by the charitable contributions raised by Rood voor Altijd / Minke Verstrepen, donated through the AMC Foundation (amcfoundation.nl). Neither the funding organizations, nor the participating commercial partners had or will have any role in the design of the study, or the analysis and interpretation of data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

FRvdS and MEB were primarily responsible for drafting this protocol. They are also primarily responsible for the protocol implementation. SAG assists in protocol implementation. LABJ, BJK, CCvdW and JWRH are the principal investigators for this project and as such collaborated on the design of this protocol and the supervision of the 1st authors. JWRH conceived of the study and functions as the project leader. All authors contributed to the refinement of this manuscript and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This protocol, its amendments, and all associated documents (e.g., participant information form & informed consent form) have been reviewed and approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Amsterdam UMC / AMC. This study is registered with the Central Committee on Research Involving Human Subjects (CCMO) of the Netherlands under number NL63961.018.18. Should additional amendments arise, then these will be submitted to the aforementioned Medical Ethics Committee. Participants are all adults and all give written informed consent before enrolment. All study data are processed under a code, which is only accessible to researchers directly involved with the project or persons performing monitoring functions (e.g., the Medical Ethics Committee). Personal information is processed according to the provisions of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation. This research is conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Radboudumc has developed the earliest version of the Spirofind as an in-house assay. The license was obtained by Boulder Diagnostics (Boulder, Colorado, USA), subsequently acquired by Oxford Immunotec (Oxford, UK). In 2018, the license was returned to Radboudumc; Oxford Immunotec is no longer involved in the development of the assay. Radboudumc has additionally received a grant from Boulder Diagnostics (later Oxford Immunotec) for an unrelated project. To secure the independence the study, the Amsterdam UMC functions as the Sponsor of the study, all samples are blinded prior to processing, including any information related to type (case or control) and time point. Samples are processed at two separate sites, and outcomes for all tests from both sites will be compared.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

(1) Specifics of laboratory measurements. (2) Questionnaires. (3) Sample size calculation. (PDF 378 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

van de Schoor, F.R., Baarsma, M.E., Gauw, S.A. et al. Validation of cellular tests for Lyme borreliosis (VICTORY) study. BMC Infect Dis 19, 732 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4323-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-019-4323-6