Abstract

Background

Chronic active Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) disease (CAEBV) is defined as a severe, progressive lymphoproliferative disorder associated with active EBV infection persisting longer than 6 months and developing in patients without recognised immunodeficiency. Rarely, interstitial pneumonitis (IP) occurs as a serious complication in CAEBV patients. The standard therapeutic regimen for IP in CAEBV has not yet been defined. Although interferon alpha (IFN-alpha) is known to suppress viral DNA replication by affecting its basal promoter activation process, it is rarely used in CAEBV patients.

Case presentation

A 22-year-old Caucasian woman, diagnosed with CAEBV 1.5 years earlier, was admitted to the Immunology Clinic due to a 4-week history of productive cough, fever and general weakness. Cultures of blood, urine and sputum were negative, but EBV DNA copies were found in the sputum, whole blood, isolated peripheral blood lymphocytes as well as in the blood plasma. Cytokine assessment in peripheral blood revealed the lack of IFN-alpha synthesis. Disseminated maculate infiltrative areas in both lungs were observed on a computed tomography (CT) chest scan. The patient was not qualified for the allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) due to the risk of immunosuppression-related complications of infectious IP. Inhaled (1.5 million units 3 times a day) and subcutaneous (6 million units 3 times a week) IFN-alpha was implemented. To the best of our knowledge, this was the first documented use of inhaled IFN-alpha in a patient with CAEBV and concomitant IP. Patient’s status has improved, and she was eventually qualified to allo-HSCT with reduced conditioning. Currently, the patient feels well, no EBV was detected and further regression of pulmonary changes was documented.

Conclusions

CAEBV should be considered in patients who present with interstitial lung infiltration and involvement of other organs. Although more promising results have been obtained with allo-HSCT, inhaled IFN-alpha may also be a therapeutic option in patients with CAEBV and a concomitant IP.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Detection of Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection, acute or chronic, may be an important finding during differential diagnosis of autoimmune systemic disorders. Primary EBV infection manifests clinically as mononucleosis, a self-limiting disease lasting no longer than 2-3 weeks [1, 2]. Chronic active Epstein-Barr virus disease (CAEBV) is defined as a severe, progressive lymphoproliferative disorder associated with active EBV infection persisting longer than 6 months and developing in patients without recognised immunodeficiency [3]. This life-threatening condition is characterised by markedly elevated levels of antibodies against EBV or EBV deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) in the blood and EBV ribonucleic acid (RNA) or protein in lymphocytes in tissues. Most patients present with fever, hepatic dysfunction, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and thrombocytopenia. Other features, found in more than 10% of patients, include hepatomegaly, anaemia, rash, oral ulcers, haemophagocytic syndrome, coronary artery aneurysms, liver failure and lymphoma. Rarely, interstitial pneumonitis (IP) occurs as a serious complication of CAEBV [4,5,6]. Standard therapeutic regimen for CAEBV-associated IP has not yet been defined. Although interferon alpha (IFN-alpha) is known to suppress viral DNA replication by affecting its basal promoter activation process, it is rarely used in patients with this condition. We present the case of a 22-year-old woman with CAEBV and IP, who due to treatment with IFN-alpha, could be eventually qualified for a successful allo-HSCT procedure.

Case presentation

A 22-year-old Caucasian woman, diagnosed with CAEBV 1.5 years earlier, was admitted to the Immunology Clinic due to a 4-week history of productive cough, fever and general weakness. Previously, the patient had been receiving antibiotics for a month in an outpatient setting, but no significant improvement was observed [7].

The patient had been diagnosed with infectious mononucleosis at the age of 17 years, with resultant significant deterioration of her status lasting for 6 months. She was eventually hospitalized due to leucopoenia, anaemia, splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy and liver dysfunction. Antinuclear antibody titre was 1:80, the ENA (extractable nuclear antigen) panel and antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) yielded negative results, and C3, C4 complement concentrations were normal.

Despite extensive diagnostic workup, including, among others, bone marrow and liver biopsy, a diagnosis has never been established.

During subsequent two years, the patient was rehospitalized a few more times, and periodically received treatment with granulocyte colony-stimulating factors (G-CSF) and corticosteroids. At the age of 20 years, the woman underwent splenectomy due to hypersplenism and splenomegaly. Six months later she was diagnosed with CAEBV, according to the Okano criteria 2005 [8] i.e.: 1) persistent or recurrent infectious mononucleosis-like symptoms; 2) an unusual pattern of EBV antibodies with elevated anti-VCA (viral capsid antigen) and anti-EA (early antigen), or detection of the EBV genome in affected tissues including the peripheral blood; and 3) chronic illness that cannot be explained by any other known disease processes at the time of diagnosis. In situ hybridisation (ISH) staining of spleen specimens revealed expression of EBV latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1) and EBV-encoded small RNAs (EBERs) in T lymphocytes (T-cell type infection). After these findings, the patient was put on immunostimulatory treatment with thymus peptides. The woman has never smoked or used other tobacco products, and has never been exposed to inhalant irritants. She also had no family history of pulmonary malignancies or other lung diseases.

At the time of admission to the Immunology Clinic, the patient had no fever. Neither respiratory failure or cyanosis were observed. No abnormalities were found on physical examination, except for axillary and inguinal lymph node enlargement (up to 1 cm), and single bilateral wheezes audible above the region corresponding to middle and lower lung fields.

Patient’s haemoglobin concentration was 9.9 g/dl and her WBC (white blood cells) amounted to 6300/μl, with 20.5% of lymphocytes, 66.6% of neutrophils and 6.5% monocytes. The other parameters of the blood were as follows: platelets 607,000/μl, ESR (erythrocyte sedimentation rate) 120 mm/h, CRP 8.71 mg/dl, aspartate aminotransferase 126 u/l, alanine aminotransferase 88 u/l, total bilirubin 0.14 mg/dl and D-dimers 1817 ng/ml. The results of kidney function tests and electrolyte levels were normal.

Bacterial (aerobic and non-aerobic) and fungal cultures were carried out under standard conditions, and yielded no pathogens. Also polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based testing for genetic material of hepatitis C virus (HCV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), herpes simplex virus 1 and 2 (HSV-1 and -2), cytomegalovirus (CMV), human papillomavirus (HPV), parvovirus B19, influenza virus, Borrelia burgdorferi, Chlamydia trachomatis, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Toxoplasma gondii, Ureaplasma spp. and Listeria spp. yielded no positive results. EBV DNA copies were found in the sputum, whole blood, isolated peripheral blood lymphocytes as well as in the blood plasma (Fig. 1). Other potential pathogens causing the condition were excluded.

Serum cytokines i.e.: granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), IFN-gamma, interleukin (IL)-1-beta, IL-2, IL-4, IL-5, IL-6, IL-7, IL-8, IL-10, IL-12 (p70), IL-13, and tumour necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha were measured by the use of the Multiplex MAP high sensitivity human cytokine panel (Millipore), following the manufacturer’s instructions, similar as described previously by Cohen et al. [6]. The results were as follows: GM-CSF: 4639.97 pg/mL, IFN-gamma: > 2500 pg/mL, IL-1-beta: 23.72 pg/mL, IL-2: 13.91 pg/mL, IL-4: 6.16 pg/mL, IL-5: 174.77 pg/mL, IL-6: > 750 pg/mL, IL-7: 75.19 pg/mL, IL-8: 625.08 pg/mL, IL-10: > 6000 pg/mL, IL-12 (p70): 1978.23 pg/mL, IL-13: 27.65 pg/mL, TNF-alpha: > 1750 pg/mL. Concentration of IFN-alpha was determined with Human IFN-alpha ELISA kit (Thermo Fischer Scientific) and Human IFN-alpha ELISA Kit (R&D Systems). The concentration of IFN-alpha was assessed in serum, saliva, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) culture supernatant. The assays yielded no detectable levels of this cytokine.

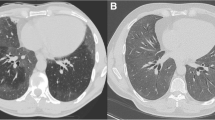

Clear lung fields and normal cardiac and mediastinal silhouettes could be observed on chest radiograph. However, disseminated maculate infiltrative areas in both lungs, more prevalent on the right side, were observed on a CT chest scan (Fig. 2, AFK scans). Abdominal ultrasound revealed enlarged liver with highly heterogeneous echogenicity, but without evident focal changes, enlarged (up to 10 mm) paraaortic lymph nodes, small volume of free fluid in minor pelvis and post-splenectomy status. No other abnormalities were found. The patient was disqualified as for the allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (allo-HSCT) due to the risk of immunosuppression-related complications of infectious IP [3, 4].

Consecutive CT scans obtained from the patient: AFK – before introduction of IFN-alpha (14-Jan-2013), BGL – during treatment with subcutaneous IFN-alpha (11-Apr-2013), CHM – during treatment with subcutaneous IFN-alpha (6-May-2013), DIN – before introduction of inhaled IFN-alpha (27-May-2013), EJO – during treatment with subcutaneous IFN-alpha and inhaled IFN-alpha (27-Jun-2013)

Long-term treatment with subcutaneous IFN-alpha was implemented (3 million units, 3 times a week) [9]. However, patient’s condition deteriorated three months later: April 2013 she presented with fever, persistent cough and was in generally poor physical health (Fig. 2, BGL). The dose of IFN-alpha was escalated to 6 million units 3 times a week, but still with no significant clinical improvement. CT performed one month later (May 2013) revealed only partial regression of pulmonary changes (Fig. 2, CHM). Therefore, the patient was referred to the Pulmonology Clinic. She had 67.81% of lymphocytes with 94.19% CD3 T cells, CD4/CD8 ratio equal to 11.35 (Table 1). Owing to poor response to previous treatment, inhaled IFN-alpha (1.5 million units 3 times a day) was added (Fig. 2DIN). To the best of our knowledge, this was the first documented use of the inhaled IFN-alpha in a patient with CAEBV and concomitant IP. Patient’s status has finally improved after 10 days of treatment.

Furthermore, partial regression of pulmonary changes was observed on a CT scan obtained one month later (Fig. 2EJO, June 2013). Figure 1 presents changes in EBV DNA copy numbers during the treatment.

The patient was qualified to allo-HSCT with reduced conditioning, which was carried out 6 months later (December 2013). Currently, the patient feels well, no EBV was detected in whole blood, blood plasma, PBMCs and sputum, and further regression of pulmonary changes was documented.

Discussion and conclusions

Interstitial pneumonia is a diffused chronic interstitial lung disease associated with inflammation and/or fibrosis of the alveolar walls [10]. Three pulmonary manifestations associated with EBV infection: hilar/mediastinal lymphadenopathy, pleural effusion, and IP have been described in literature [5]. EBV-associated IP may be triggered by drugs, occupational exposure, hypersensitivity reactions and infections; some cases are, however, idiopathic [11]. Clinical presentation is dominated either by inflammatory changes or by fibrosis. Concomitant IP is rarely observed during the course of in T-cell CAEBV, but still may develop in ca. 5% of patients with the latter condition [11, 12]. Symptoms are not specific, and include chronic cough, tachypnoea, dyspnoea and fever [10,11,12,13,14]. Only few reports describe IP as a complication of chronic active EBV infection in immunocompetent patients.

Successful outcomes in IP depend mainly on appropriate identification of an underlying pathology [10,11,12]. IFN-alpha is a recognised immunomodulatory therapy to suppress viral replication by inhibiting basal transcription processes. IFN-alpha was shown to be effective in patients with CAEBV [15, 16]. Sakai et al. reported the application of IFN-alpha to patients with CAEBV resulting in unremarkable suppression of lymphocyte proliferation [16]. In the case studied by Mitsui et al., treatment with IFN-alpha temporarily attenuated clinical symptoms: fever, skin and mucosal lesions, but the patient eventually developed pulmonary effusion and died of cardiac insufficiency [7]. A number of other therapies have been tried for CAEBV including antiviral agents: acyclovir, ganciclovir, immunomodulators: interleukin (IL)-2, chemotherapy: etoposide, corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and EBV-specific cytotoxic T cells (CTLs) [2,3,4, 6, 7, 16,17,18,19,20]. Recently, more promising results have been obtained with HSCT. HSCT may eliminate EBV-infected cells, reconstitute EBV-specific cellular immunity, and trigger a graft-versus-tumour effect. However, the procedure is associated with high risk of transplantation-related complications and the 5-year survival rate was only 53% [6].

5-year survival rate in patients with CAEBV is estimated at 59% [2,3,4]. IP is a serious and life-threatening complication of CAEBV [2,3,4]. In our patient, the disease was diagnosed late, 3 years after primary EBV infection. The course of the disease was then complicated by IP. To the best of our knowledge, there is no published information about the inability to synthesize IFN-alpha and a link between this pathology and CAEBV with IP development. Considering lack of IFN-alpha and the fact that the patient failed to be qualified for HSCT at any transplantation centre, we have implemented the treatment which has been previously used in some centres [6]. During initial 14 weeks, long-term treatment with subcutaneous IFN-alpha was implemented (3 million units, 3 times a week), which corresponded to a cumulative dose of 117 million units. In April 2013, the dose was escalated to 6 million units 3 times a week; this regimen was continued for 4 weeks (72 million units overall). Altogether, 189 million units of IFN-alpha were administered subcutaneously. In May 2013, we continued subcutaneous IFN-alpha (6 million units 3 times a week) and added inhaled one (1.5 million units 3 times a day). We prepared the inhaled IFN-alpha solution, using Roferon®-A (Interferon alfa-2a 3 MIU solution for injection, Roche). Using a pneumatic inhaler, 2 ml of the mixture were delivered over 5 min. Each 2-ml dose contained Roferon®-A – half of a labelled dose (3 million IU in 0.5 ml), i.e. 1.5 million IU in 0.25 ml, mixed with 1.75 ml 0.9% physiological saline. To the best of our knowledge, this route of administration has not been used thus far. Already after 10 days of treatment (after a cumulative dose of 45 million units of inhaled IFN-alpha and 18 million units of subcutaneous IFN-alpha), an improvement was observed, but the treatment was continued for another 15 weeks (1.5 million units 3 times a week, altogether 67.5 million units of inhaled IFN-alpha and 270 million units of subcutaneous IFN-alpha), till 10 September 2013, when due improvement of clinical status, the patient was qualified for HSCT. Overall, the patient received 112.5 million units of inhaled IFN-alpha and 477 million units of subcutaneous IFN-alpha). We summarized the treatment phases on Fig. 1, along with DNA EBV copy numbers at various timepoints. Obtained results revealed that IFN-alpha (subcutaneous and inhaled) was effective in controlling the inflammatory process, and the patient could be eventually qualified for a successful HSCT.

In conclusion, the CAEBV disease should be considered in the differential diagnosis of patients with systemic symptoms. IP is life-threatening condition which may be caused by infection with EBV. Inhaled IFN-alpha in combination with subcutaneous IFN-alpha might be a therapeutic option in patients with CAEBV and concomitant IP and should be investigated more thoroughly.

Abbreviations

- allo-HSCT:

-

Allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- ALT:

-

Alanine aminotransferase

- ANCA:

-

Antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibody

- AST:

-

Aspartate aminotransferase

- BAL:

-

Bronchoalveolar lavage

- CAEBV:

-

Chronic active Epstein-Barr virus disease

- CMV:

-

Cytomegalovirus

- CRP:

-

C reactive protein

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CTLs:

-

Cytotoxic T cells

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic acid

- EA:

-

Early antigen

- EBERs:

-

EBV-encoded small RNAs

- EBV:

-

Epstein-Barr virus

- ENA:

-

Extractable nuclear antigen

- ESR:

-

Erythrocyte sedimentation rate

- G-CSF:

-

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factors

- GM-CSF:

-

Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- HBV:

-

Hepatitis B virus

- Hct:

-

Haematocrit

- HCV:

-

Hepatitis C virus

- Hgb:

-

Haemoglobin

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- HPV:

-

Human papillomavirus

- HSCT:

-

Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation

- HSV-1 and − 2:

-

Herpes simplex virus 1 and 2

- i.v.:

-

Intravenous

- IFN-alpha:

-

Interferon alpha

- IL:

-

Interleukin

- IP:

-

Interstitial pneumonitis

- ISH:

-

In situ hybridisation

- LMP1:

-

Latent membrane protein 1

- PBMCs:

-

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PLT:

-

Blood platelets

- RNA:

-

Ribonucleic acid

- RT-PCR:

-

Reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction

- TNF:

-

Tumour necrosis factor

- VCA:

-

Viral capsid antigen

- WBC:

-

White blood cells

References

Kimura H, Hoshino Y, Kanegane H, Tsuge I, Okamura T, Kawa K, Morishima T. Clinical and virologic characteristics of chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection. Blood. 2001;98(2):280–6.

Kimura H, Morishima T, Kanegane H, Ohga S, Hoshino Y, Maeda A, Imai S, Okano M, Morio T, Yokota S, et al. Prognostic factors for chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection. J Infect Dis. 2003;187(4):527–33.

Gotoh K, Ito Y, Shibata-Watanabe Y, Kawada J, Takahashi Y, Yagasaki H, Kojima S, Nishiyama Y, Kimura H. Clinical and virological characteristics of 15 patients with chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection treated with hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46(10):1525–34.

Cohen JI, Kimura H, Nakamura S, Ko YH, Jaffe ES. Epstein-Barr virus-associated lymphoproliferative disease in non-immunocompromised hosts: a status report and summary of an international meeting, 8-9 September 2008. Ann Oncol. 2009;20(9):1472–82.

Joo EJ, Ha YE, Jung DS, Cheong HS, Wi YM, Song JH, Peck KR. An adult case of chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection with interstitial pneumonitis. Korean J Intern Med. 2011;26(4):466–9.

Cohen JI, Jaffe ES, Dale JK, Pittaluga S, Heslop HE, Rooney CM, Gottschalk S, Bollard CM, Rao VK, Marques A, et al. Characterization and treatment of chronic active EpsteinBarr virus disease: a 28year experience in the United States. Blood. 2011;117(22):5835–49.

Mitsui H, Komine M, Shirai A, Kanda N, Asahina A, Okochi H, Hitomi S, Kimura S, Tamaki K. Chronic active EB virus infection complicated with IgG3 subclass deficiency: an adult case treated with intravenous immunoglobulin and IFN-alpha. Acta Derm Venereol. 2003;83:31–5.

Okano M, Kawa K, Kimura H, Yachie A, Wakiguchi H, Maeda A, Imai S, Ohga S, Kanegane H, Tsuchiya S, et al. Proposed guidelines for diagnosing chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection. Am J Hematol. 2005;80(1):64–9.

Owusu Sekyere S, Suneetha PV, Hardtke S, Falk CS, Hengst J, Manns MP, Cornberg M, Wedemeyer H, Schlaphoff V. Type I interferon elevates co-regulatory receptor expression on CMV- and EBV-specific CD8 T cells in chronic hepatitis C. Front Immunol. 2015; https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2015.00270.

Iannella H, Luna C, Waterer G. Inhaled corticosteroids and the increased risk of pneumonia: what's new? A 2015 updated review. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2016;10(3):235–55.

Cunha BA, Gian J. Diagnostic dilemma: Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infectious mononucleosis with lung involvement or co-infection with Legionnaire's disease? Heart Lung. 2016;45(6):563–6.

He H, Wang Y, Wu M, Sun B. Positive Epstein-Barr virus detection and mortality in respiratory failure patients admitted to the intensive care unit. Clin Respir J. 2017;11(6):895–900.

Ankermann T, Claviez A, Wagner HJ, Krams M, Riedel F. Chronic interstitial lung disease with lung fibrosis in a girl: uncommon sequelae of Epstein-Barr virus infection. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2003;35(3):234–8.

Pfleger A, Eber E, Popper H, Zach MS. Chronic interstitial lung disease due to Epstein-Barr virus infection in two infants. Eur Respir J. 2000;15(4):803–6.

Trigg ME, de Alarcon P, Rumelhart S, Holida M, Giller R. Alpha-interferon therapy for lymphoproliferative disorders developing in two children following bone marrow transplants. J Biol Response Mod. 1989;8(6):603–13.

Sakai Y, Ohga S, Tonegawa Y, et al. Interferon-a therapy for CAEBV chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection: potential effect on the development of T-lymphoproliferative disease. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 1998;20(4):342–6.

Kawa K, Sawada A, Sato M, Okamura T, Sakata N, Kondo O, Kimoto T, Yamada K, Tokimasa S, Yasui M, et al. Excellent outcome of allogeneic hematopoietic SCT with reduced-intensity conditioning for the treatment of chronic active EBV infection. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2011;46(1):77–83.

Watanabe Y, Sasahara Y, Satoh M, Looi CY, Katayama S, Suzuki T, Suzuki N, Ouchi M, Horino S, Moriya K, et al. A case series of CAEBV of children and young adults treated with reduced-intensity conditioning and allogeneic bone marrow transplantation: a single-center study. Eur J Haematol. 2013;91(3):242–8.

Ishida Y, Yokota Y, Tauchi H, Fukuda M, Takaoka T, Hayashi M, Matsuda H. Ganciclovir for chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection. Lancet. 1993;341(8844):560–1.

Sawada A, Inoue M, Kawa K. How we treat chronic active Epstein-Barr virus infection. Int J Hematol. 2017;105(4):406–18.

Funding

This work was supported by research grants no. UMO-2016/21/B/NZ6/02279 and no. UMO-2012/05/B/NZ6/00792 of the Polish National Science Centre, and no. DS460 of the Medical University of Lublin. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JR, EG, AP, MD, FB, MP and ES cared for the patient and provided clinical data and materials. JR, EG, AS, VOW, MM and PG analyzed and interpreted routine diagnostic results. EG, JR, MD and VOW wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Lublin (Decision No. KE-0254/227/2010).

Consent for publication

Written informed consent for publication of their clinical details and/or clinical images was obtained from the patient. A copy of the consent form is available for review by the Editor of this journal.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Roliński, J., Grywalska, E., Pyzik, A. et al. Interferon alpha as antiviral therapy in chronic active Epstein-Barr virus disease with interstitial pneumonia - case report. BMC Infect Dis 18, 190 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3097-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-018-3097-6