Abstract

Background

Decisions on adoption of technological innovation are difficult for manufacturers, especially for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) who have limited resources but often drive product development. Decision analytic methods have been applied to regulatory issues in the nanotechnology sector but such applications to market innovation are not found in the literature. Value of information (VoI) is a decision analytic method for quantifying the benefit of acquiring additional information to support such analyses that can be used to help in a wide range of manufacturing decisions.

Results

This paper develops a VoI methodology for comparative evaluation of technological alternatives and applies it to a real case study aimed at the selection between a coating system containing nano-TiO2 and alternative conventional paints. The aim of this approach is to aid SMEs and larger industries in deciding whether to further develop the nano-enabled product and in evaluating to which extent investing in more research about risks and/or benefits would be worthwhile.

Conclusions

Results demonstrated how prioritization in information gaining can improve risk–benefit analyses and impact on both risk management and innovation decision making. By applying the proposed methodology, SMEs and larger industries might easily identify optimal data gathering and/or research strategies to formulate solid development and risk management plans.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Technology innovation is often stalled due to an inability to quantify benefits, costs and risks associated with new materials and products [1, 2]. Nanotechnology is one example where benefits may be considerable but both uncertain product risk during the research and development phases as well as consumer and environmental risks during the use phase can be potentially large and very uncertain.

Traditionally, uncertainty is reduced through collection of data. While the simplest uncertainty reduction procedure involves dealing with the most uncertain aspects first to effectively obtain substantial reductions, this choice might not necessarily impact decisions about selecting the safest and most economically viable technological alternatives. A different approach should be pursued which prioritizes uncertainty reductions according to their uncertainty reduction effects in the decisional process.

Value of information (VoI) analyses have been developed and used specifically to assess the influence of uncertainty reduction (due to acquisition of new and improved information) on management decisions [3, 4]. Similar to traditional sensitivity and uncertainty analysis, VoI analyses are concerned with the influence of uncertain parameters and model structures on model outcomes, but the focus is not on performance of individual model outputs, but rather on the change in ranking of management alternatives available to decision makers. Thus, some of the model parameters may be very uncertain, but irrelevant to the management decisions, while others may have much less uncertainty but more relevance. VoI applications start with a primary decision model which is subject to further quantitative analysis on the impact of new information.

Applications of VoI have been growing in recent years in fields including medicine, environment, and economics [5]. Application of VoI for nanomaterial risk management has been proposed in Linkov et al. [6] and Bates et al. [7]. The first study proposes a general framework for VoI application for nanomaterials while the second study applies it for a generic case of selecting experiments to make a better decision on material classification using risk banding tools. The VoI approach has not been used in the context of actual technology selection.

This work is based on the application of a risk/benefit assessment based VoI procedure applied to a real case study related to nano-TiO2 enriched coating Paint. Paint has been applied to protect building exteriors for centuries, but nano-enabled coatings can result in decreased paint volume and increased longevity and adds unique self-cleaning surface properties. The mechanisms of action include nano-TiO2 particles to decompose organic materials, pollutants, solids or gases in the presence of water, oxygen and solar radiation. A recent study by Hischier [8] shows medium expected risks to public health and environment, mainly driven by those of potential inputs into the environment and to a lower extent by the toxicity of nano-TiO2. At the same time, high risks are expected for occupational health in the manufacturing and processing phase.

Uncertainty associated with risk estimates is very high, so additional information on exposure and toxicity of nanomaterials may be required to enhance confidence in consumers and producers of the nano-enabled paint. Nevertheless, the exposure and toxicity is driven by many uncertain parameters and pathways and the question of which experiments would be of most value in reducing such uncertainty is very important for businesses to address before committing to produce nano-enabled paints.

To drive the decision whether to reduce uncertainty on risks or benefits, it has been decided to apply the proposed VoI methodology to results coming from the Licara nanoSCAN (LnS) tool specifically developed to this aim by TNO during the Licara EU Project (7th Framework Programme G. A. 315494). LnS is a modular web-based tool that developed to support SMEs in assessing benefits and risks associated with new or existing nano-enabled products [9].

Materials and methods

Licara NanoScan

The LnS tool was used in our study as the core decision model. This tool was developed within the FP7 LICARA project specifically for Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs), who often do not have the resources and expertise to apply complex decision support systems [9]. Therefore, LnS is a user-friendly screening-level tool with relatively low data requirements that provides a semi-quantitative evaluation of the environmental, social and economic benefits and the ecological, occupational and consumer health risks of nanomaterials in products from lifecycle perspective. Thanks to its application in the Licara project case studies, it has proven to be a useful tool to assist SMEs in checking supplier risks, competing products, market opportunities or making an internal risk and benefit analysis.

LnS is based on a series of multiple choice questions to evaluate economic, societal and environmental benefits as well as public health, environmental, occupational and consumer risks (the complete list of questions is reported in Additional file 1: S1: Licara NanoScan questions). LnS performs weighted sum of relative benefits and risks of the assessed nano-solution compared against the corresponding conventional product. Benefits and risks are both composed by three specific categories. Benefits are subdivided in economic, societal and environmental (following sustainability guidelines [10]) while risks are composed by Public health and environmental, occupational health and consumer health. For each category a set of multiple choice questions is used to evaluate its benefit/risk status which is afterwards aggregated into the global benefit/risk. Answers are unrelated to each other so that neither synergic nor redundant effects are present. The evaluation is performed by means of weighted sum (default weights are set to equally distribute importance at each hierarchical level, users can change weights if deemed necessary) of values associated to each user choice so that the result is a normalized benefit/riskpair in the two-dimensional [0, 1]2 result space.

LnS is intended to be a screening first tier tool for SMEs, it is therefore foreseen that, in some cases, the user may not know the answer to specific questions. For this purpose, in each question, the “I don’t know” option is available. This lack of information introduces uncertainty in the result which LnS represents by uncertainty bars. Inputs to the presented generalized VoI methodology consist in random variables related to two categories of data, risks and benefits.

VoI methodology

The methodology presented in this work builds on Bates et al. [7]. While that previous work was focused on information portfolios for risk classification, the present methodology focuses on both risks and benefits in a two-act selection problem. Comparing to the previous work this novel methodology is based on risk/benefit assessment and not just risk and has been applied to a real case study for demonstration.

We consider a technology to have various risks and benefits. Specifically, let \( {\mathbf{r}} = \left( {r_{1} , \ldots ,r_{I} } \right), \;\;\;r_{i} \in \left[ {0,1} \right] \) denote the risk factors for a technology, and \( {\mathbf{b}} = \left( {b_{1} , \ldots , b_{J} } \right), \;\; b_{j} \in \left[ {0,1} \right] \), denote the benefit factors. We assign to each risk a weight \( w_{i}^{r} \) between 0 and 1, and to each benefit a weight \( w_{j}^{b} \) between 0 and 1, with \( \sum\nolimits_{i} {w_{i}^{r} } = 1 \) and \( \sum\nolimits_{j} {w_{j}^{b} } = 1. \) We consider the total risk of a technology to be \( r = \sum\nolimits_{i} {w_{i}^{r} } r_{i} \) and the total benefit to be \( b = \sum\nolimits_{j} {w_{j}^{b} } b_{j} \), and note that \( r \in \left[ {0,1} \right] \) and \( b \in \left[ {0,1} \right] \).

We shall use capital letters to denote random variables, and lower-case letters to denote the values they take. Thus, if we consider risks and benefits to be uncertain, \( \phi_{{R_{i} }} \) and \( \phi_{{B_{j} }} \) denote the probability density function for the random variables Ri and Bj associated with the risks and benefits, while \( \phi_{{R_{i} }} \left( {r_{i} } \right) \) and \( \phi_{{B_{j} }} \left( {b_{j} } \right) \) denote the functions evaluated at specific values ri and bj.

We let E[X] denote the expectation (or expected value) of random variable X over its range X(Ω), i.e., \( \smallint_{{{\text{X}}(\varOmega )}} x\phi \left( X \right)\, {\rm d}x \). Note that \( E\left[ R \right] = \sum _{i} w_{i}^{r} E\left[ {R_{i} } \right] \) and \( E\left[ B \right] = \sum _{j} w_{j}^{b} E\left[ {B_{j} } \right] \).

Associated with the technology is a decision \( d \in D \) about its treatment. For each technology, we allow a binary treatment about the decision—the technology is (ultimately) either accepted (d1) or rejected (d0), this is referred as a two-action problem [11].

Finally, there is a function \( L\left( {d, r, b} \right): D \times \left[ {0,1} \right]^{2} \to \left[ {0,1} \right] \), defining the loss that occurs (or equivalently, the utility gained) when decision d is taken about the technology with risk r and benefit b. We calculate \( \left[ {L\left( {d, R, B} \right)} \right] = \mathop \smallint \nolimits_{B\left( \varOmega \right)}^{{}} \mathop \smallint \nolimits_{R\left( \varOmega \right)}^{{}} L\left( {d,r,b} \right)\phi \left( r \right)\phi \left( {b|R = r} \right) \, {\rm d}r{\rm d}b, \) the expected loss of a decision about the technology made under uncertainty over its risks and benefits.

There are various loss functions that might be used in this problem. (1) A classification loss function, as has been used in risk-regulation models. Bates et al. [7] mapped risk scores to two numerical ranges which we paraphrase as “should accept” and “should reject.” A table defines the loss associated with (erroneously) assigning a risk into a given class when, with perfect information, it would be classified in a different category, while the loss of correctly assigning a risk is, by definition, zero. This can be thought of as the loss for selecting given alternative under uncertainty when perfect information might have indicated some other alternative should be selected. A more refined calculation of loss involves some direct numerical calculation of the loss resulting from each option in each state. For two-action problems, (2) the linear loss function [11] is often most appropriate. If a direct value of the ongoing activity can be calculated, the decision maker has an option to halt the activity if that value is negative, thus avoiding potential loss, while there is no loss associated with pursuing the activity if the value is positive (or if the default decision is to not pursue the activity, then in cases where it would positive value, this potential value can be viewed as opportunity loss for selecting the ‘reject’ alternative). Finally [7] also illustrated the use of (3) a quadratic loss function (in a sense, a generalization of the classification loss function), where the loss associated with assuming an estimated risk score as opposed to the actual risk score is proportional to the square of the error in the estimate. Note this loss function is of a slightly different form as it essentially treats the estimate itself as a decision variable. In some cases, such loss functions are driven by the structure of the possible actions and payoffs, while in others they are coarse approximations of actual payoffs. Because of the nature of quadratic loss which represents an error rather than a direct value (as in the other two cases), a normalization step is applied which consists in dividing the quadratic loss by the range of its possible values, this makes quadratic loss results comparable to others. We will demonstrate value of information calculations with all three of these methods.

We introduce a term for the value of the technology (if launched), v = b − r. In case (1), L(d0, r, b) = 0 if v ≤ 0 and 1 if v > 0, and L(d1, r, b) = 1 if v < 0 and 0 if v ≥ 0. In case (2) L(d0, r, b) = max (0, v), and L(d1, r, b) = max (− v, 0). In case (3) L(d0, r, b) = 0 if v ≤ 0 and (v* − v)2 if v > 0, and L(d1, r, b) = (v* − v)2 if v < 0 and 0 if v ≥ 0, where v* is defined as the value related to perfect information on r and b.Footnote 1

We calculate the following \( E\left[ {L\left( {d , R,B} \right)} \right] \) for d0 and d1. We also calculate \( L\left( {d, r, b} \right) \) for d0 and d1, for each possible pair of values \( r, b \), i.e., \( \left\{ {\left( {r,b} \right)|r \in \left( {r_{1} , \ldots ,r_{I} } \right), b \in \left( {b_{1} , \ldots , b_{J} } \right)} \right\} \). Let d*(r, b) denote argmindL(d, r, b) and d′ denote argmindE[L(d, R, B)] and let L* be E[L(d*, R, B)] and L′ be E[L(d′, R, B)].

In this decision problem, the expected value of perfect information on b and r is equal to L′ − L*. When it is possible to obtain information, it is often useful to distinguish between decisions involving the selection of the final action (d0 or d1 in our case) and strategies (which specify information acquisition plans as well as the final action to be selected after specified information has been acquired). Our problem can be represented with a decision tree, where we associate d* with the strategy of selecting the initial branch which obtains information about r and b first, followed by a decision selecting d0 or d1, L* is the expected loss of this branch, i.e., expected value of perfect information (EVPI), while d′ represents the strategy of selecting the initial branch where d0 or d1 is selected and then information is revealed about the value of L, and L′ is the expected loss at this branch, i.e., Expected Value (EV). This can be generalized to strategies which involve obtaining partial information prior to selecting d. In particular, we consider strategies db which obtains perfect information about b and no information about r prior to selecting d, and dr which obtains perfect information about r and not b prior to making the decision. The associated losses Lr and Lb represent expected value of imperfect information (EVII).

The distribution of L under different states of information can be obtained in several ways, depending on the inputs and the needs of the problem. (1) Enumeration. If there are relatively few variables and relatively few possible discrete states (in the study here, the low, baseline and high estimates for each of the ri and bj are assumed to be equally probable), direct calculation of loss and probability associated with each possible combination of states is straightforward. (2) With more variables and states (or possibly continuous states), Monte Carlo analysis can be used with some trade-off of computational overhead and fidelity. (3) With a large number of variables, analytical solutions can be obtained using a normal approximation (i.e., by central limit theorem) for the sum of random variables with known or calculable means and variances (as is often done with binomial variables, as well as other variables, e.g., triangular or log normal task times in project management summing to an approximated normal project time).

We will demonstrate value of information calculation with methods 1 and 3; for the latter case, we note that E[v] = E[b] − E[r], and as all of the ri and bj are independent, \( {\text{Var}}\left[ V \right] = \sum _{i} \left( {w_{i}^{r} } \right)^{2} {\text{Var}}\left[ {R_{i} } \right] + \sum _{j} \left( {w_{j}^{b} } \right)^{2} {\text{Var}}\left[ {B_{j} } \right] \). Once mean and variance of the value function are obtained losses for the different methods (classification, linear and quadratic) can be calculated by multiplying the probability of value being in the loss area for each decision (e.g., P(v ≤ 0) for d1) by the loss function of the method (i.e., 1 for classification, v for linear and (v* − v)2 for quadratic).

Case study

The presented case study is based on Hischier [8] and relates to the comparison of two façade coating paints based on titanium dioxide (TiO2). The two paintings differ as the first contains pigment-grade TiO2 while the second nano-grade TiO2. We are facing in this case the two selection problems of deciding whether staying with the conventional non-nano product or move to the nano-based solution. The use of nano TiO2 has demonstrated to increase lifetime of the paint due to a photocatalytic self-cleaning effect. The characteristics of the two compared alternatives are reported in Table 1.

This paper presents a Value of Information assessment based on results from van Harmelen et al. [9] where LnS was applied to several case studies including the one about nano-TiO2 based façade coatings presented here.

The experimental setting for our VoI assessment consists in the list of LnS answers from one industrial partner of the Licara project about the comparison between conventional and nano-based façade coatings. The full set of inputs consists in 28 answers related to Benefits and 11 related to Risks. Each answer has an associated value which LnS uses to calculate overall benefit/risk value by weighted average. The VoI assessment was based on the five unknowns present in the answers, one in benefits and four in risks.

Results

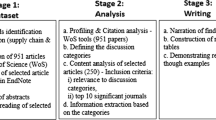

LnS computes a weighted sum of relative benefits and risks (as presented in Additional file 1: S1: Licara NanoScan questions) of a nanotechnology application as compared to the corresponding conventional product (Fig. 1 left, LnS only plots the positive benefits area). In the presented case study, weights were kept equally distributed as in LnS default settings, more specific weight profiles can nevertheless be applied [12, 13, 14]. The presented case study was characterized by 5 unknowns each with 3 possible states choices which generated 35 = 243 possible result points, as depicted in the bubble chart to the right of the LnS results space (zoomed into the region of interest) as in Fig. 1.

Initial data (from LnS) and uncertainties. On the left, the original LnS result space is presented. The result is depicted as a blue dot with uncertainty bars, the results domain is subdivided into four areas: “No-Go”, “Research on risks”, “Go” and “Research on benefits”. On the right side, the result area is zoomed in and a bubble chart is presented which depicts all possible results due to uncertainty. The area of each bubble represents its point’s probability. The three vertical “stripes” which are clearly visible in the right side are due to the fact that there is only one benefits’ unknown which has three possible different states while the higher number of points along each stripe derives from the integration of the four risks’ unknowns permutations

We consider a technology to have various uncertain risks and benefits which are characterized by a probability density function. Associated with the technology is a decision about whether it is (ultimately) accepted or rejected, which is a two-action problem. Finally, there is a loss that occurs or a utility that is gained in terms of risk or benefit when a decision is taken about the technology.

We applied three different loss functions: classification, linear and quadratic. For the classification case, VoI is the expected reduction of the probability of technology being given the wrong classification, possibly weighted by the importance of different misclassifications; for the linear case, VoI is the expected gain in the expected multi-criteria score of the best option; while for the quadratic case VoI is the expected squared difference between the estimated multi-criteria score and the multi-criteria score under perfect information.

Finally, we defined two strategies for imperfect information gathering, or in other words two sources of imperfect information: Research on risks and Research on benefits. The two strategies are imperfect as the former supplies perfect information about risks but no information about benefits while the latter supplies the opposite.

The proposed VoI assessment calculates expected Value of Imperfect Information by the losses associated to the two strategies for the classification, linear and quadratic loss functions (cf. Fig. 2). It is clear from the results that the Research on risks strategy tends to have fewer associated losses (i.e., the related probabilities’ bars are always on the left side of the chart relatively to the other’s), as its losses are always lower or equal to the Research on benefits strategy.

Probability mass function of loss results. Probability mass function of loss results for enumeration input both for “Research on risks” in blue and “Research on benefits” in orange are reported for the classification, linear and quadratic loss functions. Because of the different natures of the quadratic loss function (i.e., error based vs value based), it is not meaningful to compare its absolute values with others, nevertheless the comparison is still sound in terms of comparing the patterns of the two sources of information along the different loss functions as well as relative comparisons inside single functions

More precisely, as reported in Table 2, with the classification loss function Research on risks reduces loss to about one third the level that to which Research on benefits reduces loss while under linear loss the situation is even more in favor of Research on risks. Finally, in the quadratic loss setting Research on risks results is one sixth as much loss of Research on benefits.

EV has been calculated as the loss L′ related to taking a decision prior to any information. The three loss functions (classification \( L_{c}^{{\prime }} \), quadratic \( L_{q}^{{\prime }} \) and linear \( L_{l}^{{\prime }} \)) have been applied to the two selected types of inputs (enumeration and normal approximation) obtaining the results reported in Table 2. Results related to the quadratic loss function in the Normal approximation setting are not present as by definition error of expected value of v is always zero. In addition, EVPI has been calculated as the difference between L′ and L* which represents loss after gaining perfect information about both risks and benefits for the three loss functions \( L_{c}^{*} \), \( L_{q}^{*} \) and \( L_{q}^{*} \) as reported in Table 2.

We define an unknown’s configuration as a set of LnS answers where each unknown of the original case study setting is replaced by a given value. By examining the resulting probability distributions over the multicriteria score associated with configurations, it is possible to understand which unknowns’ configurations yield the lowest losses for each strategy and understand if any configuration is always present.

The Research on benefits strategy deals with only one unknown (Additional file 1: B1.1.4 in S1: Licara NanoScan questions) whom lowest loss configuration answer is “Worse” which calls for the “Reject” decision (see Additional file 1: Table S1 in S2: EV calculations). The Research on risks strategy instead presents four unknown questions and seven configurations all yielding the same lowest loss of zero. In three cases, the “Accept” decision is selected, among those, the configuration with “Hours” answer for the first question (Additional file 1: R1.2.2) and “< 5 kg” for the other three (Additional file 1: R1.3.1, R1.3.3 and R1.3.4) is always present. In the other four cases, the “Reject” option is selected and again a configuration is always present consisting in the “Months” answer for the first question (R1.2.2) and “> 500 kg” for the other three questions (Additional file 1: R1.3.1, R1.3.3 and R1.3.4, see Table S1 in S2: EV calculations).

Finally, a factors prioritization setting-based sensitivity analysis [15] has been performed across the five unknowns to establish which questions can most reduce the total variability of the technology’s valuation. The process demonstrated (see Additional file 1: Table S2 in S3. Sensitivity analysis) that the questions “Efforts needed to produce the product using the nanomaterial?” and “What is the stability (half-life) of the nanoparticles present in the nanomaterial under ambient environmental conditions?” (Additional file 1: B1.1.4 and R1.3.1 in S1: Licara NanoScan questions) are the most important ones.

Discussion

This paper has illustrated the use of a VoI approach by applying it to a real case study involving the comparative risk–benefit assessment a nano-enabled paint application. This example clearly shows the value of learning in the process of comparing novel products to their conventional counterparts to select alternatives that are optimal in terms of risks, costs and benefits. The results have shown that the new information gained on these aspects can improve risk–benefit analyses, which can have a significant impact on both risk management and innovation decision making. Therefore, by applying the proposed methodology to their actual products, both SMEs and larger industries can more easily identify optimal data gathering and/or research strategies to acquire the information needed to formulate viable R&D and/or risk management plans.

It is clear that the assessment of which source of imperfect information has the highest expected value is not limited to nanotechnologies but is applicable to all situations where uncertainty is present and could be mitigated by means of external resources. Therefore, in addition to risk–benefit analysis, the same VoI approach can be applied also to other activities such as lifecycle, socioeconomic, supply chain or cost-benefit analyses. In all cases, the VoI ensures that data acquisition is focused on creating value by affecting future decisions instead of gathering information only to reduce uncertainty, which makes the approach very useful for managing risk mitigation and product portfolios.

Indeed, the VoI model proposed here suggests that learning should not relate to reducing the highest technological and/or risk-related uncertainties, but to providing answers to the questions that would most strongly influence the ranking of alternative options. This requires an understanding of which uncertainties are most important for corporate R&D and risk managers, which can be only obtained if these stakeholders are actively engaged in the decision analytical process. Nevertheless, it should be noted that according to previous research some information regarding criteria that are not highly weighted by the stakeholders can often make information relating to criteria that are highly valued even more important for improving decision confidence [7]. Even when such synergetic effects are apparently small, they demonstrate the value of a formal stochastic investigation of the performance of alternatives from multiple perspectives, as intuition alone is insufficient to understand the interaction between different uncertainties. Such an investigation can be performed by combining the VoI approach with multi-criteria decision analysis [5].

Conclusion

VoI can serve as an effective decision analytical framework that cannot only direct the reduction of uncertainties, but can also provide the means to measure the sensitivity to new information to support decision makers from SME and larger companies in setting adequate research agendas that aim at creating highest learning value at the lowest possible cost. In this context, the information obtained from the VoI analysis can be useful not only to select the right technological alternatives but also to identify adequate risk management strategies to obtain anticipated benefits at optimal costs. This can be achieved for example through exploring options for safer design of high-quality products by means of a VoI-driven Stage-Gate decision analysis.

Notes

As the real value of v* is unknown in the proposed case study, the expected value of v has been used as a proxy for v*.

Abbreviations

- EV:

-

expected value

- EVPI:

-

expected value of perfect information

- LnS:

-

LICARA nanoSCAN

- R&D:

-

research and development

- SME:

-

small and medium enterprises

- TiO2 :

-

titanium dioxide

- VoI:

-

value of information

References

Hristozov D et al (2016) Frameworks and tools for risk assessment of manufactured nanomaterials. Environ Int 95:36–53

Zhou Z, Goh YM, Li Q (2015) Overview and analysis of safety management studies in the construction industry. Saf Sci 72:337–350

Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Walton ME, Rushworth MF (2007) Learning the value of information in an uncertain world. Nat Neurosci 10(9):1214–1221

Teunter RH, Babai MZ, Bokhorst JA, Syntetos AA (2018) Revisiting the value of information sharing in two-stage supply chains. Eur J Oper Res 270(3):1044–1052

Keisler JM, Collier ZA, Chu E, Sinatra N, Linkov I (2014) Value of information analysis: the state of application. Environ Syst Decis 34(1):3–23. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10669-013-9439-4

Linkov I, Bates ME, Canis LJ, Seager TP, Keisler JM (2011) A decision-directed approach for prioritizing research into the impact of nanomaterials on the environment and human health. Nat Nanotechnol 6(12):784–787

Bates ME et al (2015) Balancing research and funding using value of information and portfolio tools for nanomaterial risk classification. Nat Nanotechnol 11:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/nnano.2015.249

Hischier R et al (2015) Life cycle assessment of façade coating systems containing manufactured nanomaterials. J Nanopart Res 17(2):68. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11051-015-2881-0

van Harmelen T et al (2016) LICARA NanoSCAN—a tool for the self-assessment of benefits and risks of nanoproducts. Environ Int 91:150–160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2016.02.021

Elkington J (1994) Towards the sustainable corporation—win-win-win business strategies for sustainable development. Calif Manag Rev 36(2):90–100

Raiffa H, Schlaifer R (1961) Applied statistical decision theory

Corrente S, Figueira JR, Greco S, Słowiński R (2017) A robust ranking method extending ELECTRE III to hierarchy of interacting criteria, imprecise weights and stochastic analysis. Omega 73:1–17

Figueira J, Greco S, Ehrgott M, Greco S (2005) Multiple criteria decision analysis: state of the art surveys. Springer, Berlin

Zabeo A et al (2011) Regional risk assessment for contaminated sites part 1: vulnerability assessment by multicriteria decision analysis. Environ Int 37(8):1295–1306

Nossent J, Pieter E, Willy B (2011) Sobol’ sensitivity analysis of a complex environmental model. Environ Model Softw 26(12):1515–1525

Authors’ contributions

AZ collected the data and performed the application, AZ, JK and IL developed the methodology, DH and AM verified the results. All authors reviewed the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

This research was carried out under the European Union 7th Framework Program Sustainable Nanotechnologies (SUN) Project (http://www.sun-fp7.eu) and the Horizon 2020 Performance testing, calibration and implementation of a next generation system-of-systems risk governance framework for nanomaterials (caLIBRAte) Project (http://www.nanocalibrate.eu). The authors would like to thank Dr. Toon Van Harmelen, Dr. Tom N. Ligthart and Dr. Esther Zondervan-Van Den Beuken from TNO Netherlands for supplying the case study data.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The data that support the findings of this study are available from Dr. Toon Van Harmelen, Dr. Tom N. Ligthart and Dr. Esther Zondervan-Van Den Beuken from TNO but restrictions apply to the availability of these data, which were used under license for the current study, and so are not publicly available. Data are, however, available from the authors upon reasonable request and with permission of Dr. Toon Van Harmelen, Dr. Tom N. Ligthart and Dr. Esther Zondervan-Van Den Beuken from TNO.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This research was funded by the Sustainable Nanotechnologies (SUN) Project (http://www.sun-fp7.eu) Contract Number 604305 and the Performance testing, calibration and implementation of a next generation system-of-systems Risk Governance Framework for nanomaterials (caLIBRAte) Project (http://www.nanocalibrate.eu) Contract Number 686239. The funding bodies were not responsible for the design of the study or the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data. The representatives of the funding body are co-authors of this manuscript.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Additional file

Additional file 1.

Licara NanoScan questions, sensitivity analysis.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Zabeo, A., Keisler, J.M., Hristozov, D. et al. Value of information analysis for assessing risks and benefits of nanotechnology innovation. Environ Sci Eur 31, 11 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-019-0194-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12302-019-0194-0