Abstract

Background

Surgical-site infection is the most frequent health care-associated infection in the developing world, with a strikingly higher prevalence than in developed countries We studied the prevalence of resistance to antibiotics in Enterobacteriaceae isolates from surgical-site infections collected in three major tertiary care centres in Bangui, Central African Republic. We also studied the genetic basis for antibiotic resistance and the genetic background of third-generation cephalosporin-resistant (3GC-R) Enterobacteriaceae.

Results

Between April 2011 and April 2012, 195 patients with nosocomial surgical-site infections were consecutively recruited into the study at five surgical departments in three major tertiary care centres. Of the 165 bacterial isolates collected, most were Enterobacteriaceae (102/165, 61.8%). Of these, 65/102 (63.7%) were 3GC-R, which were characterized for resistance gene determinants and genetic background. The bla CTX-M-15 and aac(6′)-Ib-cr genes were detected in all strains, usually associated with qnr genes (98.5%). Escherichia coli, the most commonly recovered species (33/65, 50.8%), occurred in six different sequence types, including the pandemic B2-O25b-ST131 group (12/33, 36.4%). Resistance transfer was studied in one representative strain of the resistance gene content in each repetitive extragenic palindromic and enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus sequence-PCR banding pattern. Plasmids were characterized by PCR-based replicon typing and sub-typing schemes. In most isolates (18/27, 66.7%), bla CTX-M-15 genes were found in incompatibility groups F/F31:A4:B1 and F/F36:A4:B1 conjugative plasmids. Horizontal transfer of both plasmids is probably an important mechanism for the spread of bla CTX-M-15 among Enterobacteriaceae species and hospitals. The presence of sets of antibiotic resistance genes in these two plasmids indicates their capacity for gene rearrangement and their evolution into new variants.

Conclusions

Diverse modes are involved in transmission of resistance, plasmid dissemination probably playing a major role.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Third-generation cephalosporin-resistant (3GC-R) Enterobacteriaceae represent a major threat in both hospital and community settings worldwide [1]. The resistance is mediated mainly by acquired extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) genes carried by mobile genetic elements such as plasmids and transposons. This situation is of great concern, as ESBL enzymes can hydrolyse almost all beta-lactams (except carbapenems and cephamycins) and are frequently associated with genes that confer resistance to several other classes of antibiotic. During the past decade, CTX-M enzymes have gradually replaced the classical TEM and SHV-type ESBLs in many countries [1]. Rapid international spread of CTX-M-15 has been associated with global dissemination of Escherichia coli clones, such as sequence type 131 (ST131) harbouring bla CTX-M-15 on incompatibility group (Inc) FII conjugative plasmids [2].

Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance has emerged in Enterobacteriaceae, with three mechanisms described: Qnr, which mediates target protection; AAC(6′)-Ib-cr, which mediates drug modification; and OqxAB and QepA, which mediate drug efflux [3]. These mechanisms increase the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) of fluoroquinolones, thereby facilitating the selection of mutants with greater resistance in the presence of quinolones through sequential chromosomal mutations in genes coding for the target enzymes, DNA gyrase and DNA topoisomerase IV [3].

Surgical-site infection is the most frequent health care-associated infection in the developing world, with a strikingly higher prevalence than in developed countries [4]. The alarming global burden of avoidable complications resulting from unsafe surgery has been highlighted by the World Health Organization [5]. Few good-quality data are, however, available in Africa on the phenotypic antimicrobial resistance of strains associated with surgical-site infections, and the mechanisms underlying antimicrobial resistance are unknown. We studied the prevalence of resistance to antibiotics in Enterobacteriaceae isolates from surgical-site infections collected in three major tertiary care centres in Bangui, Central African Republic; we also studied the genetic basis for antibiotic resistance and the genetic background of 3GC-R Enterobacteriaceae.

Results

Patients, antibiotic prophylaxis, bacterial strains and antibiotic susceptibility

A total of 195 patients (97 males, 98 females; mean age, 30.9 years; median age, 29.0 years; interval, 1.0–85.0 years) with surgical-site infections were included during the study period in the general surgical departments of the Complexe Pédiatrique (n = 33), the orthopaedics department of the Community Hospital (n = 64), and the general surgery (n = 41), gynaecology (n = 46) and urology (n = 11) departments of the Amitié Hospital. Most of the operations were class I (110/195, 56.4%) in the Altemeier classification, mainly with a pre-operative physical status score of I (115/195, 59.0%). The duration of most operations did not exceed 2 h (98.0%). Antibiotic prophylaxis was administered to 193 patients (99.0%), most frequently consisting of beta-lactams (92.3%), mainly ceftriaxon (93/193, 48.2%), penicillin G (n = 68, 35.2%) and ampicillin (n = 43, 22.3%).

Of the 195 non-duplicate biological samples taken, 151 were culture positive (77.4%). As 14 cultured specimens had mixed growth, a total of 165 bacterial isolates were collected. The bacteria isolated were E. coli (n = 47), Staphylococcus aureus (n = 44), Enterobacter cloacae (n = 18), Acinetobacter baumanii (n = 11), Klebsiella pneumoniae (n = 19), Pseudomonas aeruginosa (n = 8), Proteus mirabilis (n = 8), Morganella morganii (n = 3), Salmonella spp. (n = 2), Enterobacter aerogenes (n = 2), Enterobacter amnigenus (n = 1), Enterobacter sakazakii (n = 1) and K. oxytoca (n = 1).

Neither P. aeruginosa nor A. baumanii was resistant to imipenem, whereas 9% (4/44) of S. aureus isolates were methicillin-resistant, and 63.7% (65/102) of Enterobacteriaceae (33 E. coli, 16 Enterobacter cloacae, 10 K. pneumoniae, 2 Proteus mirabilis, 1 M. morganii, 1 Enterobacter amnigenus, 1 Enterobacter sakazakii and 1 K. oxytoca) were resistant to 3GC-R antibiotics. C3G-R Enterobacteriaceae strains were resistant to all the beta-lactams tested, except for cefoxitin (24.6% resistance, only Enterobacter cloacae strains), and all were susceptible to ertapenem (MIC, < 0.008–0.25 mg/L). In addition, they were characterized by high rates of resistance to netilmicin (n = 49, 75.4%), kanamycin (n = 54, 83.3%), gentamicin (n = 61, 93.9%), tetracycline (n = 60, 92.4%), ciprofloxacin (n = 55, 84.8%) and cotrimoxazole (n = 62, 95.5%), and a high rate of susceptibility to amikacin (n = 64, 98.5%). The double-disc synergy test was positive for all strains. Older patients were more susceptible to C3G-R Enterobacteriaceae infection than younger ones (p = 0.04) (Table 1).

Antibiotic resistance determinants and replicons in C3G-R Enterobacteriaceae strains

The bla CTX-M-15 and aac(6′)-Ib-cr genes were detected in all strains. Of the 64 (98.5%) qnr-positive strains, 62 were qnrB, 56 were qnrS and none were qnrA, with 55 strains each harbouring 2 qnr genes.

REP-PCR, ERIC-PCR and multilocus sequence typing of C3G-R Enterobacteriaceae

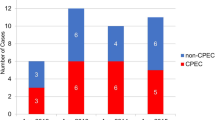

REP- and ERIC-PCR analysis showed 15 patterns for E. coli strains, 6 for Enterobacter cloacae, 5 for K. pneumoniae and 2 for P. mirabilis. Three clones were found in at least two surgical departments in the same hospital and six clones in at least two different tertiary care centres: two Enterobacter cloacae clones, three K. pneumoniae clones and three E. coli clones (Tables 2 and 3).

Six multilocus STs were found in the 33 E. coli isolates: ST131 (six clones, n = 12), ST10 (four clones, n = 12), ST405 (two clones, n = 2), ST156 (one clone, n = 5), ST354 (one clone, n = 1) and ST146 (one clone, n = 1) (Table 2). All the ST131 isolates corresponded to the multi-resistant pandemic E. coli B2-O25b-ST131 group.

Resistance transfer determination of C3G-R strains

Resistance transfer assays were performed on one strain randomly selected for each REP- and ERIC-PCR pattern. Transfer of ESBL by conjugation with E. coli J53-2 was successful for 22 (64.7%) of the 34 ESBL clones, which consisted of 17 E. coli isolates, 4 Enterobacter cloacae and 1 Enterobacter amnigenus. ESBL transfer by plasmid DNA electroporation into E. coli DH10B was successful for 5 (41.7%) of the 12 remaining isolates: 2 K. pneumoniae isolates, 2 P. mirabilis and 1 Enterobacter cloacae. The presence of bla CTX-M-15 and aac(6′)-Ib-cr was confirmed by PCR in the 27 transconjugants and transformants (Table 4). The plasmid harbouring the bla CTX-M-15 gene was systematically associated with aac(6′)-Ib-cr, in contrast to qnr genes, as no qnrS and 45.8% (11/24) of qnrB genes were co-transferred with bla CTX-M-15. Additional resistance genes (to aminoglycoside, chloramphenicol, nalidixic acid, tetracycline, sulfamide and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole) were probably transferred, as shown by antimicrobial susceptibility testing (Table 4).

Genetic support of resistance determinants

PCR-based replicon typing in the 27 transconjugants and transformants demonstrated the presence of plasmids of the incompatibility groups IncF (n = 24, 88.9%) and IncHI2 (one Enterobacter cloacae) (Table 4). The plasmid in two P. mirabilis isolates could not be typed. In the incompatibility group IncF, identical replicon ST were found in most isolates: F31:A4:B1 (n = 14, 51.9%; 11 E. coli, 2 Enterobacter cloacae and 1 Enterobacter amnigenus) and F36:A4:B1 (n = 4, 14.8%; 3 E. coli and 1 Enterobacter cloacae). These two conjugative plasmids were found in strains collected from different hospitals. The other combinations were F1:A1:B1 (one E. coli), F1:A1:B20 (one E. coli), Fnew:A-:B20 (one E. coli and one Enterobacter cloacae) and K4:-:B- (two K. pneumoniae) (Table 4).

Discussion

Enterobacteriaceae strains were the microorganisms most frequently associated with surgical-site infections, of which 65 (63.2%) were 3GC-R, as described previously in Africa [6]. Cross-transmission probably plays a major role, as suggested by the fact that patients in different surgery departments and different hospitals shared clonally related strains. This was the case not only for K. pneumoniae and Enterobacter cloacae strains, which are well known to be highly diffusible in hospital settings, especially in intensive care units [7], but also for E. coli, in contrast to the situation in developed countries [8]. Further investigations are needed to identify the mechanisms of transmission.

E. coli was the most frequent species among C3G-R Enterobacteriaceae. The 33 isolates belonged to six STs, of which three corresponded to at least two REP- and ERIC-PCR patterns, namely ST131, ST405 and ST10. The pandemic E. coli B2-O25b-ST131 group has contributed extensively to global dissemination of CTX-M-15 [2,9], as has ST405, with the dispersal of both CTX-M-15 and CTX-M-9 group enzymes [10]. In addition, ST10, which is typical in the human gut but is also responsible for intestinal and extra-intestinal infections, was recently associated with dissemination of CTX-M-1, CTX-M-2 and CTX-M-9 groups [10]. These data, combined with those from Nigeria, South Africa and Tunisia [11-13], show that dissemination of pandemic E. coli multi-drug resistant STs also occurs in African hospitals. The reasons for the wide dissemination and expansion of these clones are unknown but may include increased transmissibility, greater ability to colonize and/or persist in the intestinal tract, enhanced virulence and more extensive antimicrobial resistance than other E. coli [14]. The three minor STs have been described sporadically in humans and animals, associated with various CTX-M groups [15,16]: ST146 in Germany, ST156 in France, Great Britain and Portugal, and ST354 in Italy, Portugal and Spain. Five of the isolates found in two hospitals in this study were assigned to the ST156 genetic background, indicating its ability to spread.

Plasmid typing showed that horizontal gene transfer by IncF plasmid exchange was probably also involved in the dissemination of bla CTX-M-15. The ESBL bla CTX-M-15 gene was carried in all strains on plasmids of IncF incompatibility groups, except in one Enterobacter cloacae. IncF plasmids were the most prevalent in E. coli and K. pneumoniae carrying ESBL genes and also genes that confer resistance to tetracyclines, aminoglycosides and fluoroquinolones. These plasmids can be considered pandemic, as they have been detected in different countries and in bacteria of different origins and sources. The occurrence of these plasmid types appears to be closely linked to positive selection exerted by antibiotic use, incrementing their prevalence over that in bacterial populations that are not preselected for antimicrobial resistance. Their occurrence is also linked to virulence factors that contribute to the fitness of their bacterial host [17,18]. In the majority of isolates, including the three major E. coli STs, bla CTX-M-15 genes were found within IncF conjugative plasmids, with identical replicon ST formulae (F31:A4:B1 and F36:A4:B1), two plasmids reported to be abundant in humans [19]. The F31 and F36 alleles differ by only a single point mutation. This, in the context of the diversity of the REP- and ERIC-PCR patterns of the isolates and their presence in different species and in different hospitals, suggests that horizontal transfer of plasmids is probably an important mechanism of bla CTX-M-15 spread, as described previously [20]. The dissemination of plasmids was probably preceded by the centre-to-centre transmission of several strains by patient transfer, as indicated by the identification by REP- and ERIC-PCR of closely related K. pneumoniae, E. coli and Enterobacter cloacae isolates in at least two different hospitals.

Various sets of antibiotic resistance genes within F31:A4:B1 and F36:A4:B1 plasmids indicate their capacity for gene rearrangement and their evolution into new variants. ESBL bla CTX-M-15 and aac(6′)-Ib-cr genes were inconsistently associated with qnrB on these plasmids and also with other resistance genes, as shown by antimicrobial susceptibility testing of transconjugants. This suggests the presence of a multidrug resistance region, as described for IncFII plasmids pEK499 and pEK516 isolated in the United Kingdom from the E. coli ST131 group and for the pC15-1a plasmid disseminated in E. coli STs in Canada [20]. Further mapping of this region is needed. Frequent association of bla CTX-M-15, qnrB and aac(6′)-Ib-cr genes has been described in K. pneumoniae isolates in North, West, Central and East Africa, consistent with the hypothesis that these resistance-determinant genes are carried together on the same plasmid [21]. Such accumulation of resistance gene determinants on the same plasmid and their dissemination is a matter of concern, especially in countries with inadequate health care systems, because of the shortage of effective antibiotics and the consequences with respect to mortality, length of hospital stay and hospital costs. In addition, uncontrolled use of antimicrobial agents through self-medication, inappropriate antibiotic prescription and the substandard quality of some drugs favour the spread of antimicrobial resistance in these countries. The emergence of carbapenem resistance, which has been described in Africa [22] but was not found in our study, could be a serious challenge for infection control and antibiotic therapy in the future, as carbapenems are often the most effective antibiotics against 3GC-R Enterobacteriaceae.

Conclusions

This study is of particular importance because of the difficulty of carrying out such studies in hospitals in countries with inadequate health care systems. Our data suggest that diverse modes of transmission of resistance are involved, probably with a major role of plasmid dissemination. All necessary measures should be taken in African hospitals to prevent nosocomial infections and the selection of resistant bacteria, with efficient nosocomial infection surveillance programmes. Standard hygiene and especially adherence to hand hygiene policies are the cornerstone for preventing transmission of multidrug-resistant bacteria.

Methods

Ethical clearance

The study protocols were approved by the National Ethics Committee of Central African Republic. Written informed consent to participate in the study was obtained from all patients.

Patients

Patients with a surgical-site infection were recruited consecutively into the study between April 2011 and April 2012 in five surgical departments in three major tertiary care centres in Bangui: the Complexe Pédiatrique, the Amitié Hospital and the Community Hospital. A surgical-site infection was defined as an infection that occurred at or near a surgical incision within 30 days of the procedure or within 1 year if an implant was left in place [23]. Patients who underwent surgery were followed daily until discharge and surveillance was extended to 30 days post-operation, at a scheduled visit to the surgeon. The number of patients who did not return to the hospital and were lost to follow-up is unknown. A specific, standardized medical questionnaire was completed to collect demographic data, medical history over the previous 12 months, preoperative and postoperative antibiotic prophylaxis or treatment, type of surgery, Altemeier wound class, the American Society of Anesthesiologists’ physical status score, length of operation and delay between surgery and surgical-site infection (Table 1).

Microbiological analysis, antimicrobial susceptibility testing and detection of ESBL

After superficial cleaning of wounds with physiological saline, a specimen was collected by rotating a sterile swab across the surface of the lesion, specifically targeting moist and necrotic areas. The specimens were placed in sterile tubes without transport medium at 4°C immediately after sampling and were processed within 2 h at the Pasteur Institute medical laboratory in Bangui. Sheep blood, chocolate and bromocresol purple agar plates were inoculated, incubated aerobically at 37°C and examined after 24 h and 48 h. Obligate anaerobes were not isolated. Bacterial isolates were identified by standard microbiological methods. Antibacterial drug susceptibility was determined by the disc diffusion method on Mueller–Hinton agar (Bio-Rad, Marnes La Coquette, France), according to the guidelines of the French Society of Microbiology (http://www.sfm-microbiologie.org). Production of ESBL in C3G-R Enterobacteriaceae was detected by the double-disc synergy test [24] and the MICs of ertapenem by the E-test method (AB Biodisk, Solna, Sweden). The ertapenem cut-off values were used for categorization. Susceptible strains were defined by MIC ≤ 0.5 mg/L and resistant strains by MIC >1 mg/L. All C3G-R Enterobacteriaceae were kept for further molecular analysis.

DNA extraction and detection of beta-lactamase and plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance genes

Genomic DNA was extracted with the QIAmp™ kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France). Previously described polymerase chain reaction (PCR) methods were used to screen for plasmid-encoded bla CTX-M and bla SHV beta-lactamase genes, the aac(6′)-Ib gene and the quinolone resistance qnrA/B/S and qepA genes [24]. bla CTX-M and bla SHV were then characterized by direct DNA sequencing of the PCR products. All aac(6′)-Ib positive strains were further analysed by digestion with BtsCl (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, Massachusetts, USA) of the PCR product to identify aac(6′)-Ib-cr [24].

Repetitive extragenic palindromic PCR, enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus sequence PCR and multilocus sequence typing

In order to assess the closeness of clonal relations between isolates at the local level, repetitive extragenic palindromic-PCR (REP-PCR) and enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus sequence-PCR (ERIC-PCR) were performed with REP-1R, REP-2 T and ERIC-2, respectively, as described previously [25]. Strains with an identical ERIC-PCR and REP-PCR banding pattern were defined as clonally related.

Multilocus sequence typing of E. coli strains was performed as recommended (http://mlst.ucc.ie/) on one strain randomly selected for each of the identical REP- and ERIC-PCR banding patterns. All isolates of ST131 were analysed by duplex PCR targeting the pabB and trpA genes to determine whether the isolate belonged to the O25b-ST131 group [2].

Transferability of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase

Resistance transfer experiments were carried out on one randomly selected strain that was representative of the resistance gene content of each REP- and ERIC-PCR banding pattern. Conjugations were performed on solid media with E. coli K12 J5 resistant to sodium azide as the recipient strain [24]. Transconjugants were selected on Drigalski agar (Bio-Rad) supplemented with sodium azide (500 mg/L) and ceftazidime (4 mg/L). Transfer experiments by electroporation were performed for non-conjugative plasmids. Plasmid DNA from donors was extracted with a Qiagen plasmid midi kit (Qiagen, Courtaboeuf, France). Purified plasmids were used to transform E. coli DH10B (Invitrogen, Cergy-Pontoise, France) by electroporation according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Bio-Rad). Transformants were incubated at 37°C for 1.5 h and then selected on Drigalski agar (Bio-Rad) supplemented with 2.5 μg/mL cefotaxime. Transconjugants and transformants were tested for ESBL production followed by PCR amplification of the ESBL and plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance genes, as well as by plasmid replicon typing.

Plasmid replicon type determination

PCR-based replicon-typing analysis was performed as described previously [26]. Plasmids belonging to IncF were typed according to a replicon sequence typing scheme [27].

Data analysis

Microsoft Access 2003 was used for data entry, and Stata version 11 for statistical analysis. The chi-squared test and Student’s t test were used to compare categorical and continuous variables in univariate analysis, respectively. We considered p values < 0.05 to indicate significant associations.

Abbreviations

- ERIC-PCR:

-

Enterobacterial repetitive intergenic consensus sequence-PCR

- ESBL:

-

Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase

- 3GC-R:

-

Third-generation cephalosporin-resistant

- Inc:

-

Incompatibility group

- MIC:

-

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- PCR:

-

polymerase chain reaction

- REP-PCR:

-

Repetitive extragenic palindromic-PCR

- ST:

-

Sequence type

References

Bradford PA. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in the 21st century: characterization, epidemiology, and detection of this important resistance threat. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14:933–51.

Clermont O, Dhanji H, Upton M, Gibreel T, Fox A, Boyd D, et al. Rapid detection of the O25b-ST131 clone of Escherichia coli encompassing the CTX-M-15-producing strains. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;64:274–7.

Strahilevitz J, Jacoby GA, Hooper DC, Robicsek A. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance: a multifaceted threat. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:664–89.

Allegranzi B, Bagheri Nejad S, Combescure C, Graafmans W, Attar H, Donaldson L, et al. Burden of endemic health-care-associated infection in developing countries: systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;377:228–41.

Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, Lipsitz SR, Breizat AH, Dellinger EP, et al. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:491–9.

Bagheri Nejad S, Allegranzi B, Syed SB, Ellis B, Pittet D. Health-care-associated infection in Africa: a systematic review. Bull World Health Organ. 2011;89:757–65.

Pena C, Pujol M, Ricart A, Ardanuy C, Ayats J, Linares J, et al. Risk factors for faecal carriage of Klebsiella pneumoniae producing extended spectrum beta-lactamase in the intensive care unit. J Hosp Infect. 1997;35:9–16.

Naseer U, Natas OB, Haldorsen BC, Bue B, Grundt H, Walsh TR, et al. Nosocomial outbreak of CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli in Norway. APMIS. 2007;115:120–6.

Rogers BA, Sidjabat HE, Paterson DL. Escherichia coli O25b-ST131: a pandemic, multiresistant, community-associated strain. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66:1–14.

Naseer U, Sundsfjord A. The CTX-M conundrum: dissemination of plasmids and Escherichia coli clones. Microb Drug Resist. 2011;17:83–97.

Aibinu I, Odugbemi T, Koenig W, Ghebremedhin B. Sequence type ST131 and ST10 complex (ST617) predominant among CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli isolates from Nigeria. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2012;18:E49–51.

Ben Sallem R, Ben Slama K, Estepa V, Jouini A, Gharsa H, Klibi N, et al. Prevalence and characterisation of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Escherichia coli isolates in healthy volunteers in Tunisia. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;31:1511–6.

Peirano G, van Greune CH, Pitout JD. Characteristics of infections caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli from community hospitals in South Africa. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2011;69:449–53.

Banerjee R, Johnson JR. A new clone sweeps clean: the enigmatic emergence of Escherichia coli sequence type 131. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58:4997–5004.

Bonnedahl J, Drobni M, Gauthier-Clerc M, Hernandez J, Granholm S, Kayser Y, et al. Dissemination of Escherichia coli with CTX-M type ESBL between humans and yellow-legged gulls in the south of France. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5958.

Coque TM, Novais A, Carattoli A, Poirel L, Pitout J, Peixe L, et al. Dissemination of clonally related Escherichia coli strains expressing extended-spectrum beta-lactamase CTX-M-15. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:195–200.

Karisik E, Ellington MJ, Pike R, Warren RE, Livermore DM, Woodford N. Molecular characterization of plasmids encoding CTX-M-15 beta-lactamases from Escherichia coli strains in the United Kingdom. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;58:665–8.

Sherley M, Gordon DM, Collignon PJ. Species differences in plasmid carriage in the Enterobacteriaceae. Plasmid. 2003;49:79–85.

Carattoli A. Plasmids in Gram negatives: molecular typing of resistance plasmids. Int J Med Microbiol. 2011;301:654–8.

Dolejska M, Brhelova E, Dobiasova H, Krivdova J, Jurankova J, Sevcikova A, et al. Dissemination of IncFII(K)-type plasmids in multiresistant CTX-M-15-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates from children in hospital paediatric oncology wards. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;40:510–5.

Breurec S, Guessennd N, Timinouni M, Le TA, Cao V, Ngandjio A, et al. Klebsiella pneumoniae resistant to third-generation cephalosporins in five African and two Vietnamese major towns: multiclonal population structure with two major international clonal groups, CG15 and CG258. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2013;19:349–55.

Moquet O, Bouchiat C, Kinana A, Seck A, Arouna O, Bercion R, et al. Class D OXA-48 carbapenemase in multidrug-resistant enterobacteria, Senegal. Emerg Infect Dis. 2011;17:143–4.

Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999;20:250–78.

Harrois D, Breurec S, Seck A, Delaune A, Le Hello S, Pardos de la Gandara M, et al. Prevalence and characterization of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing clinical Salmonella enterica isolates in Dakar, Senegal, from 1999 to 2009. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2014;20:O109–16.

Eckert C, Gautier V, Saladin-Allard M, Hidri N, Verdet C, Ould-Hocine Z, et al. Dissemination of CTX-M-type beta-lactamases among clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae in Paris, France. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1249–55.

Carattoli A, Bertini A, Villa L, Falbo V, Hopkins KL, Threlfall EJ. Identification of plasmids by PCR-based replicon typing. J Microbiol Methods. 2005;63:219–28.

Villa L, Garcia-Fernandez A, Fortini D, Carattoli A. Replicon sequence typing of IncF plasmids carrying virulence and resistance determinants. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:2518–29.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank François-Xavier Weill and Simon Le Hello (Institut Pasteur, Unité des Bactéries Pathogènes Entériques, Paris, France) for providing the positive control strains and all the clinicians involved in the conduct of this study. This study was supported by local funds from the Institut Pasteur of Bangui.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Conception and design of the study and acquisition of data: CR, TF, AM, AG, LN, ES, BT, BG, SB. Molecular and genetic studies, molecular analysis: TF, JRM, SB. Analysis of results: CR, TF, AM, JRM, SB. Draft of the manuscript: CR, TF, AM, BG, SB. Review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: BG, SB. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Rafaï, C., Frank, T., Manirakiza, A. et al. Dissemination of IncF-type plasmids in multiresistant CTX-M-15-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates from surgical-site infections in Bangui, Central African Republic. BMC Microbiol 15, 15 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-015-0348-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-015-0348-1