“I pass through the streets of my country, looking at the national flags hanging from both sides, I feel proud, I feel happy, I do not care that the streets are dirty and collapsed...I’d rather pass through the dirt roads filled with my people and culture, than paved and well made, but empty of my beloved nation.”

– Anonymous.

Abstract

This research investigates the relationship between national identity and public goods provision across a wide range of countries. The analysis shows that national identity, measured based on survey data, and public goods provision, measured by a broad set of indicators, are negatively related. This result is explained through a proposed short-run model on country stability, where the provision of national identity and public goods are substitutable. The findings challenge the conventional wisdom on nation-building as a policy tool for mitigating the adverse effects of fractionalization, suggesting that generally it is used as a tool for governments to divert the attention of its citizens from most pressing issues, such as the provision of elementary public goods.

Source: World Value Survey (average for 1981–2014). The darker shades indicate stronger national identity; the white shades indicate no availability of data

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

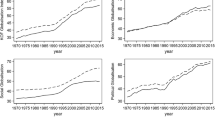

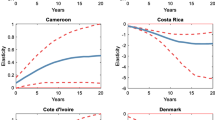

The first subsection of the third section presents the rest of the figures.

Note that there are some conventional forms of public goods provision that can also be used for spreading national identity, such as education. In that case, the provision of national identity goods entangles with public goods provision. The purpose of this research is not to disentangle this relationship, but to investigate the relationship between national identity and the provision of public goods, which are not directly and necessarily used for spreading national identity.

The persistence of the national identity measure also excludes the possibility of a longitudinal analysis.

Table 6 shows that illiteracy loses its significance due to inclusion of a dummy variable for Europe and Central Asia, which indicates that the strong positive correlation between illiteracy and national identity is mainly driven by that region, where illiteracy and national identity are at their lowest levels compared to other regions.

The correlation between absolute latitude and GDP per capita in the sample is 0.6.

The “Western Europe” classification is borrowed from the CIA World Factbook.

The second subsection of the fourth section quantifies the proposed measure of stability and shows that it is positively correlated with a well-known index of stability.

It is reasonable to assume diminishing returns to scale, \(\alpha <1\) and \(\beta <1\); however, the subsequent exploration of the model is not dependent on this assumption and holds for any level of \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\).

An individual utility maximization problem can be set up to derive the amount of tax collected in the country; it will be a function of the weight citizens give to public goods versus private goods and will be directly proportional to the overall wealth of the individuals (country). However, this approach is more relevant for representative democracies and less applicable to a global cross-country setting.

Note that \(c_{x} x\) and \(\beta y\) can alternatively viewed as linear production functions of public goods and national identity.

The positive relationship between the amount of tax collected and level of national identity, for example, has been shown by Johnson (2015), who studied the eighteenth-century France and found that regions with higher tax collection had higher level of national identity.

As Tables 1 and 2 show fractionalization is associated with lower public goods provision, however, the coefficient is not significant for several indicators, which have previously shown to have a negative correlation with fractionalization (Desmet et al. 2012). This might be due to the inclusion of an additional variable on national identity and its dominating adverse effect on public goods provision.

There are only 5 countries in the sample which record national identity lower than 2.8

References

Ahlerup, P., and G. Hansson. 2011. Nationalism and government effectiveness. Journal of Comparative Economics 39(3): 431–451.

Akerlof, G.A., and R.E. Kranton. 2000. Economics and identity. Quarterly Journal of Economics 115: 715–753.

Alesina, A., R. Baqir, and W. Easterly. 1999. Public goods and ethnic divisions. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 114(4): 1243–1284.

Alesina, A., A. Devleeschauwer, W. Easterly, S. Kurlat, and R. Wacziarg. 2003. Fractionalization. Journal of Economic growth 8(2): 155–194.

Alesina, A., and B. Reich. 2013. Nation building, Technical report, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Angrist, J.D., and J.-S. Pischke. 2008. Mostly harmless econometrics: An empiricist’s companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Banerjee, A., L. Iyer, and R. Somanathan. 2005. History, social divisions, and public goods in rural India. Journal of the European Economic Association 3(2–3): 639–647.

Barro, R.J., and J.W. Lee. 2013. A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950–2010. Journal of Development Economics 104: 184–198.

Benabou, R., and J. Tirole. 2003. Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. The Review of Economic Studies 70(3): 489–520.

Berry, W.D., M. Golder, and D. Milton. 2012. Improving tests of theories positing interaction. The Journal of Politics 74(3): 653–671.

Bockstette, V., A. Chanda, and L. Putterman. 2002. States and markets: The advantage of an early start. Journal of Economic Growth 7(4): 347–369.

Centeno, M.A. 2002. Blood and debt: War and the nation-state in Latin America. University Park: Penn State Press.

Chen, Y., and S.X. Li. 2009. Group identity and social preferences. The American Economic Review 99: 431–457.

Clots-Figueras, I., and P. Masella. 2013. Education, language and identity. The Economic Journal 123(570): F332–F357.

Cunningham, G .B. 2005. The importance of a common in-group identity in ethnically diverse groups. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice 9(4): 251.

DellaVigna, S., R. Enikolopov, V. Mironova, M. Petrova, and E. Zhuravskaya. 2014. Cross-border media and nationalism: Evidence from serbian radio in croatia. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 6(3): 103–32.

Desmet, K., I. Ortuño-Ortín, and R. Wacziarg. 2012. The political economy of linguistic cleavages. Journal of Development Economics 97(2): 322–338.

Desmet, K., S. Weber, and I. Ortuño-Ortín. 2009. Linguistic diversity and redistribution. Journal of the European Economic Association 7(6): 1291–1318.

Dimitrova-Grajzl, V., J. Eastwood, and P. Grajzl. 2016. The longevity of national identity and national pride: Evidence from wider europe. Research & Politics 3(2): 2053168016653424.

Dogan, M. 1994. The decline of nationalisms within Western Europe. Comparative Politics 26(3): 281–305.

Donaubauer, J., B. Meyer, and P. Nunnenkamp. 2014. A new global index on infrastructure: Construction, rankings and applications. Technical report, Kiel Working Paper.

Dovidio, J.F., and S.L. Gaertner. 2000. Aversive racism and selection decisions: 1989 and 1999. Psychological Science 11(4): 315–319.

Dovidio, J.F., S.L. Gaertner, and T. Saguy. 2009. Commonality and the complexity of “we”: Social attitudes and social change. Personality and Social Psychology Review 13(1): 3–20.

Eckel, C.C., and P.J. Grossman. 2005. Managing diversity by creating team identity. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 58(3): 371–392.

Fearon, J.D. 2003. Ethnic and cultural diversity by country. Journal of Economic Growth 8(2): 195–222.

Habyarimana, J., M. Humphreys, D.N. Posner, and J.M. Weinstein. 2007. Why does ethnic diversity undermine public goods provision? American Political Science Review 101(04): 709–725.

Han, K.J. 2013. Income inequality, international migration, and national pride: A test of social identification theory. International Journal of Public Opinion Research 25: 502–521.

Harttgen, K., and M. Opfinger. 2014. National identity and religious diversity. Kyklos 67(3): 346–367.

International Social Survey Programme: National Identity. 1995, 2003, 2013. GESIS Data Archive, Cologne.

Johnson, N.D. 2015. Taxes, national identity, and nation building: Evidence from france. George Mason University working paper.

Kaufmann, D., A. Kraay, and M. Mastruzzi. 2011. The worldwide governance indicators: methodology and analytical issues. Hague Journal on the Rule of Law 3(02): 220–246.

Klor, E.F., and M. Shayo. 2010. Social identity and preferences over redistribution. Journal of Public Economics 94(3): 269–278.

La Porta, R., F. Lopez-de Silanes, and A. Shleifer. 2008. The economic consequences of legal origins. Journal of Economic Literature 46(2): 285–332.

La Porta, R., F. Lopez-de Silanes, A. Shleifer, and R. Vishny. 1999. The quality of government. Journal of Law, Economics, and organization 15(1): 222–279.

Lan, X., B. Li, et al. 2015. The economics of nationalism. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy 7(2): 294–325.

Lewis, B. 1975. History: Remembered, recovered, invented. New York City: Touchstone.

Manning, A., and S. Roy. 2010. Culture clash or culture club? national identity in britain*. The Economic Journal 120(542): F72–F100.

Masella, P. 2013. National identity and ethnic diversity. Journal of Population Economics 26(2): 437–454.

Mayda, A.M., and D. Rodrik. 2005. Why are some people (and countries) more protectionist than others? European Economic Review 49(6): 1393–1430.

Mayer, T., and S. Zignago. 2011. Notes on cepii’s distances measures: The geodist database.

Miguel, E. 2004. Tribe or nation? Nation building and public goods in kenya versus tanzania. World Politics 56(03): 328–362.

Miguel, E., and M.K. Gugerty. 2005. Ethnic diversity, social sanctions, and public goods in Kenya. Journal of Public Economics 89(11): 2325–2368.

Motyl, A.J., and M.R. Beissinger. 2001. Encyclopedia of nationalism, vol. 2. San Diego: Academic Press.

Robinson, A.L. 2014. National versus ethnic identification in Africa: Modernization, colonial legacy, and the origins of territorial nationalism. World Politics 66(04): 709–746.

Shayo, M. 2009. A model of social identity with an application to political economy: Nation, class, and redistribution. American Political Science Review 103(02): 147–174.

Shulman, S. 2003. Exploring the economic basis of nationhood. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 9(2): 23–49.

Suesse, M. 2018. Breaking the unbreakable union: Nationalism, disintegration and the soviet economic collapse. The Economic Journal 128(615): 2933–2967.

Tajfel, H., and J.C. Turner. 1979. An integrative theory of intergroup conflict. The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations 33(47): 74.

Tilly, C. 1994. States and nationalism in europe 1492–1992. Theory and Society 23(1): 131–146.

West, T.V., A.R. Pearson, J.F. Dovidio, J.N. Shelton, and T.E. Trail. 2009. Superordinate identity and intergroup roommate friendship development. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 45(6): 1266–1272.

World Development Indicators. 1984–2013. World Bank Group, World Bank Publications.

World Value Survey. 1981–2014. World Values Survey Association (www.worldvaluessurvey.org). LONGITUDINAL AGGREGATE v.20150418.

Zeileis, A., and G. Yang. 2013. pwt: Penn World Table. R package version 7.1-1. http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pwt.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank anonymous referees, the editor, Klaus Desmet, Ruben Enikolopov, Giacomo De Luca, Gunes Gokmen, Omer Ozak, Jonathan Solis, Maurits van der Veen, and Shlomo Weber for helpful discussions and comments and to the participants of the 2017 NES-HCEO Summer School, 2017 Annual Workshop of the IRES at Chapman University, 2017 Annual Conference of the Association for the Study of Religion, Economics, and Culture (ASREC), VIVES (Research Centre for Regional Economics) seminar at KU Leuven and the 4th Euroacademia International Conference “Identities and Identifications: Politicized Uses of Collective Identities.” All remaining errors are mine

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Infant | Illitiracy | Schooling | Infrastructure |

|---|---|---|---|

Mortality | Rate | Years | Quality |

HH | HH | HH | HH |

Australia | Uzbekistan | Australia | Kuwait |

Trinidad& Tobago | Australia | ||

Qatar | |||

HL | HL | HL | HL |

Tanzania | Pakistan | Rwanda | Ecuador |

Ghana | Mali | Pakistan | Tanzania |

Bangladesh | Egypt | Tanzania | El Salvador |

Pakistan | Tanzania | Mali | Colombia |

Burkina Faso | Ghana | Guatemala | Yemen |

Mali | Burkina Faso | Yemen | Zimbabwe |

Yemen | Yemen | Bangladesh | Bangladesh |

Rwanda | Bangladesh | Ghana | |

Rwanda | |||

LH | LH | LH | LH |

France | Moldova | Estonia | Czech Rep |

Belarus | Bosnia& Herz | Japan | Estonia |

Belgium | Latvia | Lithuania | Belgium |

Denmark | Lithuania | Hong Kong | Sweden |

Estonia | Russia | Germany | France |

Switzerland | Belarus | Sweden | Denmark |

Sweden | Bulgaria | Slovakia | South Korea |

Japan | Estonia | Netherlands | Germany |

Czech Rep | Serbia | Belgium | Japan |

South Korea | Ukraine | Bulgaria | Slovakia |

Bosnia&Herzeg | Ukraine | Bahrain | |

Netherlands | Czech Rep | Belarus | |

Slovakia | Denmark | Ukraine | |

Lithuania | Switzerland | Switzerland | |

Germany | Russia | China | |

South Korea | Netherlands | ||

Hong Kong | |||

LL | LL | LL | LL |

NONE | NONE | NONE | NONE |

See Fig. 8 and Tables 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12.

National identity and other public goods outcomes. Notes: the figures depict the relationship of national identity with measures of health care and access to public services. The grids are defined based on the lower and upper quartiles of the two measures. Most of the countries are located in the HL or LH segment, and a few countries are in the HH segment. There are no countries in the LL segment with an exception of Lebanon, which together with low national identity records also low immunization rate

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Harutyunyan, A. National Identity and Public Goods Provision. Comp Econ Stud 62, 1–33 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41294-019-00101-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41294-019-00101-3