Abstract

The aim of the study is to understand the role of insurance company reputation, performance, and positive/negative affect on health insurance policy customer retention and the moderating influence of customer inertia. A structured questionnaire was used for data collection. Covariance-based structural equation modeling was employed to assess the hypothesized relationships between the variables. The findings revealed that reputation, performance, and affect influenced customer retention in insurance sector. Positive affect had greater impact on customer retention in comparison to other constructs. Further, customer inertia was an important moderating influence on the negative affect for health insurance policy customer retention. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first of its kind that attempts to investigate customer inertia in the health insurance sector in an emerging market context, i.e., India. Customer inertia has not been much studied in light of company reputation, performance, and positive and negative affect in the health insurance milieu. The research findings may help health insurance companies understand the importance of reputation, performance, customer retention, and inertia while marketing insurance services.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The high-quality service delivery is the key to success in service sector. Notwithstanding the ubiquitous accessibility of a number of retail insurance avenues (i.e., life and non-life policies), customers are not fully aware of the varied options available (Barwitz 2020; Hu and Tracogna 2020). The fierce competition and continuously evolving customer expectations has compelled service companies to take steps to offer services that are focused toward enhancing service experiences, e.g., health insurance (Abu-Salim et al. 2017; Yun and Hanson 2020). Harrison (2000) recognized that the globalization of financial services has increased pressure on firms to add value to their service offerings, i.e., service quality, customer satisfaction, productivity, and costs rationalization in ever changing regulatory and technological landscape (Heckl et al. 2010; Marshall 1985).

According to PwC’s (2020) Health Insurance Consumer Pulse Survey, health insurance policy holders held favorable views toward their health insurance. However, the intense competition in the health insurance segment is of great concern for any insurance player as it leads to customer’s switching service providers (Christiansen et al. 2016; Dominique-Ferreira 2017). The retention of existing customers is crucial for any health insurance policy renewal especially in Indian market (Meesala and Paul 2018; Panda et al. 2016). Research claims that competitive services industries are less differentiated and have more intermediated levels of client satisfaction (Abu-Salim et al. 2017; Fornell and Johnson 1993). The lack of product/service differentiation culminates into competitive challenges for the insurance firms. Given the multitude of options, the insurance policy customers are demanding and choice rich, and ‘policy lapses’ increasingly become a norm. The financial service customers often pursue comparable and/or better alternatives to their existing service providers (Kannadhasan 2015; Sharma and Patterson 2000).

The theory of Status Quo Bias emphasized the possible explanations why health plan consumers choose to sustain the status quo—the perpetuation of an incumbent company’s service offerings (Samuelson and Zeckhauser 1988; Seth et al. 2020). According to Samuelson and Zeckhauser (1988), upholding the status quo is a normal action because consumers reflect the decisional impacts in terms of switching costs, price for status quo, and perceived risks associated with alternatives. Consumers often make a risk aversion-oriented decision regarding changing service provider, or switch (Masatlioglu and Ok 2005). Thus, consumers with resilient status quo bias have positive value, information, and emotional attachment, irrespective of the lucrative proposals of rival players or common pressures for change (Kahneman and Tversky 1979; Kahneman et al. 1991; Taylor 2012).

The extant literature argued that the switching costs tend to be more imperious in services, but it was difficult for customers to evaluate and differentiate similar services offered by firms (Fernandes and Pinto 2019; Gremler and Brown 1996). Keaveney (1995) provided a typology of customer reasons for service switching and measure the frequency of incidents with reasons (i.e., a service defect or failure) and conditions (i.e., change in needs). The customer reasons were classified into eight broad categories: inconvenience, pricing, core service failures, response to failed service, failed service encounters, competition, ethical concerns, and involuntary switching. East et al (2012) extended the Keaveney’s (1995) work by using the critical incident technique and suggested that in comparison to non-located service, a located service is much less conceivable to be abandoned owing to price as location may increase switching costs and/or decrease price rationales. Research suggested that the insurance service possesses high credence, complex nature, abstract evaluation, and is largely focused on futuristic benefits that are difficult to verify (e.g., life, financial or non-financial protection) (Crosby and Stephens 1987). Klemperer (1995) posits that losing customers on account of transactions switching costs not just leads to loss of available opportunities in the marketplace, but also builds pressure on the service organizations to squeeze resources to acquire new clients. Customer switching has negative consequences on companies’ market share and profitability (Ganesh et al. 2000). Thus, it becomes critical for insurance service companies to retain the existing customers and due the perilous nature of customer inertia in services.

Few researchers have attempted to understand switching costs paradigm with respect to customer retention practice, primarily for the service sector (Lam et al. 2004; Lee et al. 2001; Li 2015). The reluctance to change service provider has been attributed to customer inertia (Bawa 1990; Meidan 1996; Panther and Farquhar 2004; White and Yanamandram 2004). In the state of inertia, the customer avoids spending time to reassess the service dimensions of another company brand (Assael 1998). Disparate to other research constructs directly or indirectly influencing customer retention, consumer inertia embraces a moderating distinction that impacts the customer retention and potential behavioral antecedents such as satisfaction, regret, or disappointment (Ghose and Lowengart 2013; Oliver 1997). Despite its proven relevance and significance in service domain, the role of customer inertia in the context of financial services has not been much researched with respect to customer switching behavior (Thaichon et al. 2017).

The current study assumed that corporate reputation reduces service switching; the performance is an antecedent of customer satisfaction which also reduces switching behavior. It is anticipated that switching costs play a decisive role in determining whether the health insurance policy holder decides to stay (retained the existing policy) or exit (switched the insurance provider) from their respective service provider. According to the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority of India (IRDAI) norms, the customer may easily switch or port their existing health insurance policy to another insurance company in the case of perceived poor customer service, claim settlement issues, additional cover facility offered by any other company, and availability of better option or transparency concerns due to the health insurance company reputation (ET 2019; IRDAI 2020). In mature markets like financial services, customer retention provides a number of intrinsic benefits to the firms (Harrison and Ansell 2002; Pickett et al. 2017). The current study is an initial attempt to examine the role of insurance company reputation, insurance service performance, and positive and negative affect in facilitating customer retention in the health insurance sector and the moderating influence of customer inertia. Furthermore, we intend to test the mediating role of positive and negative affect as explanatory variables in ensuring customer retention. The subsequent sections comprise of detailed literature review, theoretical underpinning, followed by research methodology and results. At the end, we deliberate on the study findings and limitations with future research imperatives.

Conceptual framework

In the last two decades, domains like marketing, economics, sociology, and strategy observed a rising research trend related to corporate reputation and its impact on customer behavior (Chun 2005; Fombrun and Shaney 1990; Walker 2010). Corporations with higher reputation were linked with superior customer loyalty (Bartikowski et al. 2011), higher customer satisfaction (Walsh and Beatty 2007; Walsh et al. 2009), and retention (Bartikowski and Walsh 2011). Several studies have stressed the relevance of financial service company’s reputation/image (Boyle 1996; Worcester 1997; Devlin 1997; Nguyen and LeBlanc 2002; Wang et al. 2003), service quality performance (Siddiqui and Sharma 2010; Tsoukatos and Rand 2006), fairness (Page and Fearn 2005) and affective experiences (Hellier et al. 2003; Taylor 2001) as strategic factors in explaining customer retention, repurchase intentions and loyalty (Mittal and Lassar 1998; Rundle-Thiele 2005). Most studies investigated these variables separately and did not investigate their impact on loyalty. Danaher and David (2012) contended that merely improving customer satisfaction parameters may not always ensure loyalty. Factors like customer engagement, service involvement, switching costs and societal benefits also influenced satisfaction–loyalty relationship.

Literature review

Health insurance in India

The rapid growth of the health insurance services both in public and private sector has considerably influenced the healthcare scenario in the last two decades (Michielsen et al. 2011; Sen et al. 2014). Within a short span of time, private insurance players have acquired substantial market share in the Indian insurance sector (Gambhir et al. 2019). The insurance services growth potential has augmented the range of opportunities for insurance marketers in India (Dror et al. 2007; Gupta 2007). The growth has triggered intense competition in the Indian health insurance market, especially for private sector players. Thus, for long-term success in the competitive insurance market, firms are compelled to innovate their service offerings, strengthen existing delivery processes and cost rationales (Chakrabarti and Shankar 2015; Thomas and Vel 2011). Owing to rising income levels in emerging markets like India, the demand for health insurance is projected to increase which may impact the affordability for insurance products (Dragos 2014). Treerattanapun (2011) asserted that as gross domestic product (GDP) /capita increase, non-life insurance affordability also increases, especially in the context of emerging economies. The Indian health insurance sector is either state funded or publicly funded, thus insurance schemes do not totally mitigate inequitable access to health services in a private health care delivery market (Sodhi and Rabbani 2014). Indian insurance market is different from western countries where people are more aware about health-related hazards especially the adverse effects of not having medical insurance. Customers in western countries are conscientious about regular medical checkups and aware of government health and medical initiatives/facilities available for common citizens. On the contrary, in India, the accessibility to good health insurance services is limited to higher income groups due to lack of awareness, income disparity, individualistic slackness, paucity of government support etc. (Chakrabarti and Shankar 2015). Most people consider regular medical checkups and investing on health insurance a waste of resources. When people avail health insurance policy for evading taxes or getting income tax rebate or as employers’ compensation, they continue with their existing policy without much serious efforts to compare the alternatives. Therefore, the common negligence toward primary health services, lack of awareness about health issues, poor accessibility to medical facilities in smaller cities, and cost of medical checkups creates an inertia, disengagement and disinterest toward health programs or medical insurance (Sodhi and Rabbani 2014). This behavior has an impact on consumers’ perception toward insurance services that provide financial support during illness. Most Indians feel it an unnecessary expense because health-related problems are not given a serious thought barring situation like COVID-19 pandemic (ET 2020; FE 2020).

Although, health insurance sector in India is in nascent stage, still health insurance companies are expected to offer medical benefits during hospitalization, insurance policy performance (e.g., claim settlement, cashless benefits), and healthcare service quality (i.e., comfortable hospitalization, insurance coverage). As compared to other insurance products, health insurance firms need to ensure adequate level of affective service experience, customer-centric interface (i.e., easy documentation, service efficacy) and easy claim settlement (Ahlin et al. 2015; Chakrabarti and Shankar 2015). In addition, financial services performance is influenced by trust, image and reputation of the service provider (Macintosh 2009; Nienaber et al. 2014). The following sections discusses the variables taken up for the study.

Switching costs

The switching costs for insurance services include–search costs (the costs of time invested in searching for the information about claims settlement), habit (investment oriented behavior), learning (financial strength of the insurance company), inertia, costs of transaction in terms of contractual and continuity (the costs of time and effort desired for price bargain and administrative charges) as discussed by several researchers (e.g., Berger et al. 1989; Posey and Tennyson 1998; Posey and Yavas 1995; Schlesinger and Schulenburg 1991, 1993). Bell et al (2005) explored the effects of customers’ investment know-how and perceived switching costs on technical and functional service quality and customer loyalty. Increased level of perceived switching costs makes altering service providers costly and ensures a dependency of the customer on the service provider (Ruyter et al. 1998; Weerahandi and Moitra 1995). As the perceived switching costs escalate, at least in the short period of time customers are unlikely to alter the service providers (Ranaweera and Prabhu 2003).

The switching costs are acknowledged as a means for holding customers in business relationships, irrespective of their level of satisfaction with the service provider (Bansal et al. 2004; 2005; Burnham et al. 2003; Jones et al. 2002). Gremler and Brown (1996) employed in-depth interviews to understand the relevance of switching costs as an antecedent to customer loyalty. Switching costs was demarcated as investment of time, money and search efforts that in customer perception made it challenging to switch. The switching costs are formally manifested as the costs of changing the service providers owing to varied reasons (Carter et al. 2016; De Matos et al. 2013; Dick and Basu 1994). Recent studies have revealed that switching costs are diverse and multidimensional in nature (Barroso and Picón 2012; Gremler et al. 2020; Kuo 2020). Burnham et al (2003) recognized three dimensions of switching costs, each with a few subcategories, i.e., procedural, relational and financial.

Customer inertia

Inertia is described as a non-conscious form of emotion, uni-dimensional in nature entailing “passive service patronage without true loyalty” (Huang and Yu 1999). Deliberate inertia entails an intentional persistence to maintain status quo, when there are better alternatives and incentives available in market (Schwarz 2012). Schwarz (2012) categorized inertia as spontaneous, forced, unobtrusive, and deliberate inertia. The grouping is based on motivation for change (high vs low value) and the influencing condition (external vs internal). The deliberate inertia is customers’ conscious and rational decision which takes into account the value, benefits and switching costs where the role of insurance executive becomes crucial to offer better service (Terpstra and Verbeeten 2014; Yu and Tseng 2016). The inert customers are more likely to respond to various marketing activities like promotions and discounts (Huang and Yu 1999). Few scholars suggest that inertia is an outcome to avoid change or barriers to switch due to the dearth of attractive alternatives or higher switching costs. Thus, the customers prefer to stay with the existing service provider instead of exploring new options (Bodet 2008; Bozzo 2002; Picón et al. 2014). Customer inertia is the continued use and purchase of the same brand passively over a period of time without much thought (White and Yanamandram 2004). While Yanamandram and White (2006) defined inertia with respect to passivity, we propose that inertia is a much broader and complex concept (Zeelenberg and Pieters 2004).

The customer inertia originated from the Status Quo Bias (SQB) theoretical framework (Masatlioglu and Ok 2005; Samuelson and Zeckhauser 1988). Inertia is defined as the tendency to stick to the prevailing habits or course of actions even when a better decision substitute is offered or available to someone (Samuelson and Zeckhauser 1988). Other customer inertia metaphors are: status quo preservation (De Guinea and Markus 2009), consumer resistance (Mani and Chouk 2018), drive for repeat purchases (Ranaweera and Neely 2003), systematic bias (Wu et al. 2018) and loyalty or spurious loyalty (Wu and Lo 2012) which is demarcated as the condition when a customer purchases the same offering every time without conscious thinking or commitment toward company (Huang and Yu 1999). Numerous reasons can explain inertia as a phenomenon, e.g., convenience orientation, uncertainty avoidance, habitual orientation toward decision making and the risk avoidance (Lee and Joshi 2017). Moreover, inertia can be divided into two distinct measures: first, cognitive inertia and second, affective inertia (Greenfield 2005; Polites and Karahanna 2012). The cognitive inertia denotes as conscious sticking to the status quo, despite being aware of that it might not be the best option to choose, while affective inertia characterizes as sticking to the status quo because other options are observed as being difficult to acquire (Greenfield 2005; Handel 2013). A few studies on health insurance have employed inertia to describe the stickiness to the alternatives with certain risk levels (Handel 2013; Handel and Kolstad 2015). At the same time, strong empirical evidence exists to explain the persistence of inertia in investment decision making (Auger et al. 2016).

Company reputation and service performance

Company reputation as a theoretical construct echoes the broad assessment of a corporation. Though the concept is quite broad in nature, there have always been a lack of precise definitions and research scholars attempted to define it differently. The perceptual exemplification of a corporation in the minds of key stakeholders is described as the reputation of the organization (Fombrun 1996). Company reputation is understood as a set of connotations that the target customer ascribes about the company and then uses it to designate, recall and relate to the same as a consequence of positive or negative experience, favorable or unfavorable impressions, beliefs, value dispositions, feelings, information and knowledge (Dowling 2004). A good company reputation encourages product purchases in the form of simplifying customer decision making process. The service literature emphasizes the importance of firm reputation, service quality and delivery in improving customer satisfaction and performance. Nguyen and LeBlanc (1998) investigated the role of service quality, customer satisfaction with services offered and value perceptions on firm’s image and loyalty toward the banks. Customers’ perceptions about bank image and reputation influenced loyalty, while satisfaction affected loyalty more than perception of bank’s image. Andreassen and Lindestad (1998a) found that company reputation is positively correlated with customer’s gratification and loyalty toward the service. Yoon et al (1993) in their research on business insurance services posited that customer expectations, reputation and availability of information influence buying decision. Further, customers’ response to the service is consistent with their attitude toward the company reputation. Abdelfattah et al (2015) and Rahman et al (2018) analyzed the relationship between service quality, customer’s satisfaction and religiosity on the customer’s purchase and patronage behavior toward health insurance. Nguyen (2010) highlighted the importance of competence and benevolence attitudes of service staff on customers’ perception of reputation of financial service firms. In case of services, the perceptions of corporate reputation and image influence customer commitment and loyalty (Nguyen and LeBlanc 2001).

Positive and negative affect

Affect is “the psychological attachment of an exchange partner to the other and is based on feelings of identification, loyalty and affiliation” (Verhoef et al. 2002, p. 204). The affect denotes individuals’ valence response to service or products, their attributes, service staff and company for the positive or negative emotion it evokes (Ortony et al. 1988). Research examined the importance of positive affect and attitude in stressful situations; however, not enough attention has been paid to the appraisal of stressful situations, which can lead to gains for the firm by inducing positive emotions such as excitement, eagerness and confidence (Folkman 1997). Negative affect induces stress, but there are several studies that emphasized the relevance of positive affect during stressful situations (Folkman and Moskowitz 2000). Positive and negative affect varies across individuals, considerations, and situations (i.e., intensity and frequency) thus, making it difficult to understand (Diener et al. 1985). Bougie et al (2003) investigated the relevance of feeling of anger and dissatisfaction on customers’ behavior to failed service encounters across firms. Favorable or positive emotion/affect or behavioral intentions influence customer retention, and customers are less likely a switch to another service provider (Burnham et al. 2003; Colgate and Hedge 2001; Jones et al. 2007). The ‘affect’ conceptualization implies a pleasant or unpleasant state (Plutchik 2003). Steiner and Maas (2018) described that value with respect to insurance services comprises of firms, staff or agent and the insurance policy. These elements affect customer’s perception of satisfaction and trust. It is widely acknowledged that customers’ product or service consumption situations evoke positive and negative emotion (Oliver 1997). The positive and negative affect and the relationship congruence of these affects with other cognitive variables (i.e., firm reputation, service performance, and customer value) influence customer retention and satisfaction (Mano and Oliver 1993; Oliver 1993; Westbrook and Oliver 1991). On the basis of arguments presented above, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H1

A good reputation of insurance company would have a positive influence on positive affect.

H2

A good reputation of insurance company would have a negative influence on negative affect.

H3

A good performance of insurance service would have a positive influence on positive affect.

H4

A good performance of insurance service would have a negative influence on negative affect.

H5

Positive affect would positively influence customer retention.

H6

Negative affect would negatively influence customer retention.

Customer inertia, switching costs and affects

In the service marketing literature, two different perspectives emerge in explaining customer inertia as classification of switching barriers (Patterson and Smith 2003; White and Yanamandram 2004; Yanamandram and White 2006). The first perspective on customer inertia has been associated with lack of attractive alternatives (Bozzo 2002; Colgate and Lang 2001) and the second described inertia as a function of customers’ passivity, inactivity, and non-conspicuousness (White and Yanamandram 2007). Whenever insurance customers wish to change service providers, they have to incur higher search costs as well as transaction costs (Kautish and Rastogi 2008). Customers who are lethargic and find searching for new alternatives cumbersome experience inertia. The approach to avoid change and choosing to remain with current service provider suggests a behavioral lock-in effect (Barnes et al. 2004). Nevertheless, the broad consensus among researchers is that inertia explains customer’s resistance or barriers to switch and is a loyalty facilitator in service marketing (Chen and Wang 2009; Oliver 1999). Bansal and Taylor (1999) defined perceived switching barriers as consumers’ assessment of the efforts needed to explore other options to switch from an existing provider. Gray et al (2017) confirmed that inertia has a negative impact on the intention to change service providers but does not provide any evidence on its effect on the actual behavior to switch service providers. Thus, inertia has an impact on customer’s evaluations of alternatives and the customers prone to higher levels of inertia do not consider choosing alternative service providers even when they are dissatisfied (Lee 2019).

Lee and Neale (2012) related switching costs to customer inertia. They found that while inertia led to customer retention, it influenced positive or negative word of mouth. Favorable or unfavorable word of mouth depends on whether customer inertia stems from the satisfaction or lack of interest. Financial services customers experiencing higher degree of inertia are likely to purchase a specific service repeatedly (Colgate and Lang 2001). They believe that searching for new alternatives is time consuming, bothering, and labor intensive (Yanamandram and White 2006). Inertia helps in retaining customers for the company. Carter et al’s (2016) qualitative study on switching behavior and inertia revealed that the customer may avoid switching even when circumstances are conducive to changing service provider in terms of fairness and trust. The research suggested that inertia had direct and moderating effects on service provider switching intentions, though not necessarily the behavior of changing service providers (Gray et al. 2017; Lai et al. 2011). Thus, the following hypotheses are proposed:

H7a: Customer inertia would moderate the relationship between positive affect and customer retention.

H7b: Customer inertia would moderate the relationship between negative affect and customer retention.

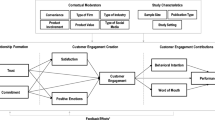

Therefore, the current research attempted to examine the relationship of insurance company reputation (ICR), insurance service performance (ISP), positive affect (PA), negative affect (NA), customer inertia on customer retention (see Fig. 1). The hypothesized model comprised of six hypotheses describing the associations among research variables. It included two hypotheses specifying the moderating influence of customer inertia.

Methodology

Measurement instrument

The survey instrument provided a description of the study objectives, and the questionnaire items were related to health insurance policy only. The questionnaire items were conceptualized from extensive literature review and adapted from previous studies (Bansal and Taylor 1999; Colgate and Lang 2001; Fombrun et al. 2000; Jones et al. 2000; Oliver and Swan 1989; Vázquez‐Casielles et al. 2010) and some items were modified according to the research context. Specifically, three-three items each were utilized to assess insurance company reputation and insurance service performance, the five items for positive affect, four items for negative affect, two items for consumer inertia and three items for understanding customer retention. All items used 7-point Likert-type scale where 7 = “strongly agree” to 1 = “strongly disagree”. The measurement instrument was pre-tested and on the basis of feedback received about language and content from two service marketing professors and four health insurance company managers. The final scale items and descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1.

Data collection and sampling

The data were collected through an online survey. A structured and open-ended questionnaire was developed about health insurance for the existing policy holders. The samples were randomly chosen with the help of two private health insurance companies’ database. The procedure began with an explanation about the underlined objectives of the study through an email invitation. The detail explanation about health insurance policy, service quality, performance, and feedback were given in the email. In addition, to ensure the information credibility insurance company executives were also involved in the initial phase of the research (Robson and Sekhon 2011). Based on the policy descriptions, respondents whose policy renewals were due in the next three months and had availed the minor or major medical claim from the company in last two years were only eligible. The respondents were emailed an URL and requested to fill the questionnaire after answering the screening question of policy renewal. Total 400 e-mails requests sent to the policy holders to fill the questionnaire, a total of 285 received out of which 228 were utilized in the data analysis. Though the response rate was acceptable, the non-response bias test suggested by Armstrong and Overton (1977) was administered. The means for the constructs of early versus late responses were compared under the assumption that those who responded later were likely to be similar to non-respondents. No significant differences between early and late groups were reported (0.05 level), confirming the absence of significant non-respondent bias. Of these 228 respondents, 123 were males and 105 were females. The average age of the respondents was 43.2 years (range from 28 to 54 years) which clearly show the age in which usually people purchase health insurance policy in order to get health protection at late age. The respondents were well educated and more than 80% of them were graduates and post-graduates.

Results

Though all the constructs and scale items were adapted from standardized, reliable and validated scales from previous studies, still the need for dimensionality check was attained by conducting factor analytics, the measure of sampling adequacy or Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) test, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity was employed. The KMO value was 0.812, and Bartlett’s test of sphericity value was also found to be significant. Table 1 provides the details about acceptable factor loadings for each scale item of all constructs and more than the recommended threshold of 0.60 (Hair et al. 2014).

Measurement model

A confirmatory factor analysis was executed to generate the measurement model estimates. The results from the study indicated that the models’ goodness-of-fit statistics was satisfactory (χ2 = 265.069; df = 136; χ2/df = 1.949; p = 0.001; CFI = 0.974; IFI = 0.973; TLI = 0.968; RMSEA = 0.066). To evaluate the internal consistency among scale items for each latent factor, composite reliability (CR) was considered and the results revealed that the CR values ranged from 0.787 to 0.985 (Hair et al. 2014). Table 1 shows that all the CR values exceeded the threshold value of 0.70; hence it confirms the internal consistency among the scale items of each variable (Hair et al. 2014). Later, to assess the convergent validity, we assessed the average variance extracted (AVE) values. The AVE values ranged from 0.599 to 0.947 and all values were more than 0.50, thus the convergent validity was confirmed. Lastly (see Table 2), as all AVE values were larger than the correlation (squared) between variables, maximum shared variance (MSV) and average shared variance (ASV) which ensure discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker 1981).

Structural model

With the maximum likelihood estimation approach, a structural equation modeling was conducted to generate the structural model. The structural model revealed a satisfactory level of goodness-of-fit statistics (χ2 = 272.219; df = 113; χ2/df = 2.409; p = 0.001; CFI = 0.967; IFI = 0.968, TLI = 0.958; RMSEA = 0.080). The structural model χ2/df value (2.409) fell within an acceptable range from 2.00 to 5.00 (Marsh and Hocevar 1988). Furthermore, the suggested model adequately accounted for the total variance in customer retention (R2 = 0.498) and positive and negative affect as well-accounted (R2 = 0.653) and (R2 = 0.336), respectively, for by good/bad insurance company reputation (ICR) and high/low insurance service performance (ISP) (see Fig. 2 and Table 3).

Structural model. Annotation 1: ICR = Insurance company reputation; ISP = Insurance service performance; PA = Positive Affect; NA = Negative Affect. Annotation 2: Goodness-of-fit statistics: χ2 = 272.219; df = 113; χ2/df = 2.409; p = 0.00; CFI = 0.967; IFI = 0.968, TLI = 0.958; RMSEA = 0.080. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01. Annotation 3: Dotted lines indicate an insignificant impact

The hypothesized relationships were assessed. As expected, the insurance company reputation has a significant positive influence on positive affect (β = 0.337; p < 0.01) and a significant negative infleunce on negative affect (β = − 0.223; p < 0.01), thus hypothesis 1 as well as hypothesis 2 were accepted. Correspondingly, the results specified that health insurance service performance revealed a significantly positive infleunce on positive affect (β = 0.535; p < 0.01) and a significant negative infleunce on negative affect (β = − 0.396; p < 0.01) so the hypotheses 3 and 4 were accepted as the insurance claim settlement experience lead to either positive or negative affect the policy renewal behavior in the Indian context (Khare et al. 2012). The hypothesized impact of positive and negative affects on customer retention was also evaluated. As estimated, positive affect significantly influenced the growing trend for customer retention (β = 0.638; p < 0.01) which ultimately leads to health insurance policy renewal without a fail and negative affect significantly influenced the reducing trend for customer retention (β = − 0.125; p < 0.01) and the health insurance policy renewal get hold by the customer owing to either a unfavorable response from the company or due to negative perception about the company, the study result is in tandom with previous research on customer retention and insurance claim settlement (Smith et al. 2000). Hence, hypothesis 5 as well as hypothesis 6 were accepted.

We tested the indirect influence of construct variables. As displayed in the Table 2, good/bad insurance company reputation revealed a significant influence on customer retention through positive and negative affects (βICR-PAandNA-Customer Retention = 0.242; p < 0.01). High/low insurance service performance also puts forth a significant indirect influence on customer retention via positive and negative affects (βISP-PAandNA-Customer Retention = 0.388; p < 0.01). It means the high service performance leads to better company reputation hence the service performance indirectly has positive affect on customer retention, whereas, if the service performance is low it indirectly affects customer retention via negatively affecting the company reputation. Subsequently, the total effect of study variables was also tested. It was acknowledged that the positive affect (β = 0.638) comprised the highest total impact on customer retention, followed by high/low insurance service performance (β = 0.388), good/bad insurance company reputation (β = 0.242), and negative affect (β = − 0.127). Thus, we can ascertain the continous improvement and stable insurance service delivery (i.e., claim settlement) is the cornerstone for health insurance policy renewal in the Indian market (Kautish and Rastogi 2008; Khare et al. 2012).

Invariance model analyses

Prior to structural invariance, measurement invariance was carried out invariance analyses for high customer inertia (n = 82) and low customer inertia (n = 146) groups. To test customer inertia, we first compared the samples, and then merged these samples to test high and low inertia groups. Initially, a grouping was confirmed based on the findings of K-means cluster exploration. This cluster analysis is considered to be suitable when grouping survey contributors’ responses into a certain quantity of clusters (K) having comparable characteristics (Gough and Sozou 2005; Milner and Rosenstreich 2013). We fit the configural (Model 1), and metric (Model 2) models, and compared the relative fit of each successively constrained model (Satorra and Bentler 2001). The baseline or configural model (Model 1) fit statistics for high customer inertia was as follows: RMSEA = 0.06 (0.03, 0.08), CFI = 0.95, and TLI = 0.96 and for low customer inertia was as follows: RMSEA = 0.05 (0.04, 0.08), CFI = 0.96, and TLI = 0.97. These indicate adequate fit compared to predictable values for a decent fitting model (RMSEA < 0.08; TLI > 0.95; CFI > 0.95). The metric model (Model 2) constrained loadings to be the same across samples and it did not have a significantly inferior fit (χ2diff (7) = 5.07, p < 0.65). The global fit statistics for Model 2 showed a slight improvement and remained satisfactory.

Furthermore, in order to calculate the moderating influence of customer inertia, a test for metric invariance was executed (Hair et al. 2014, p. 847). Afterward, a baseline model was generated. As displayed in the Table 4, the baseline model was found to have a satisfactory model fit (χ2 = 452.459; df = 235, χ2/df = 2.048; p < 0.001, CFI = 0.953; IFI = 0.954; TLI = 0.948; RMSEA = 0.065). Then, this baseline model was matched with nested models where one specific path of interest is constrained to be equal. The findings showed that there was no statistical difference in the hypothesized relationship between positive affect and customer retention (∆χ2 [1] = 3.540; p > 0.05) which substantiate the previous results (Al-Weshah 2017). Hence, the hypothesis 7a was not accepted. Moreover, it revealed a significant difference in the relationship between negative affect and customer retention (∆χ2 [1] = 4.457; p < 0.05) so the hypothesis 7b was accepted.

Mediation

As per the recommendations of Hayes (2013), the study employed PROCESS Macro Model IV to perform the mediation analysis to understand the indirect effects of negative affect (NA) and positive affect (PA) on the association between insurance service performance (ISP) and insurance company reputation (ICR) with customer retention (CR) for health insurance policy renewal. The data analysis shows that NA and PA partially mediated the link between ICR with CR: PEDirect = 0.19, 95% confidence interval (CI) (CI 0.0868–0.2174); PEIndirect Effect (NA) = 0.17, BCa 95% (CI 0.1041–0.2215); PEIndirect Effect (PA) = 0.10, BCa 95% (CI 0.2157–0.3315). Correspondingly, both NA and PA also reasonably mediated the relationship between ISP and CR: PEDirect = 0.29, 95% (CI 0.1814–0.3238); PEIndirect Effect (NA) = 0.16, BCa 95% (CI 0.1031–0.1924); PEIndirect Effect (PA) = 0.11, BCa 95% (CI 0.1120–0.1427). The nonappearance of zeros in the bootstrapped CIs substantiates the existence of partial mediation for all the aforementioned relationships.

Theoretical contributions

The current study adds to the existing service literature by examining the influence of customer inertia, company reputation, affect, insurance service quality on customer retention in the context of insurance services. Research suggests that “desire to get satisfaction” may influence “behavioral intentions”. Nevertheless, there was a dearth of studies on customer inertia in the health insurance sector especially in emerging market context. The proposed theoretical model established the contribution of insurance company reputation, its service performance, positive and negative affect and customer inertia on customer retention in the health insurance sector. The convoluted associations of these factors have never been explored in the insurance segment. The study indicated the relevance of firm reputation, service performance on positive and negative emotion/affect and customer retention. In addition, positive and negative affect were key mediators and customer inertia acted as a moderator in the study. The findings are in tandem with the research of White and Yanamandram (2004) where they posited that awareness of customer inertia may help financial service institutions to prevent customer defections. It helps in identifying past behavior patterns which predict customers’ switching and complaining behavior. Thus, customer retention rate can improve by overcoming avoidable circumstances during the moment of truth for service performances.

The study considered the effect of customer inertia as moderator in case of positive affect as well as negative affect. Additionally, the study contributes to the existing knowledge by providing limited support for other theories attempt to explain health insurance behavior in the non-western context. Particularly, it demonstrates the support for expectation disconfirmation theory (EDT), economic cost models of consumer behavior and exploratory buyer behavior in explaining the marketing relationships that took place among Indian consumers and health insurance service providers in the market. It asserts the usability of these theories that had been developed in western culture to be used in developing country context.

Therefore, it presents a meaningful understanding of the role of inertia in influencing health insurance service switching behavior. The test for metric invariance exhibited that both high as well as low customer inertia significantly moderated the relationship between negative affect and customer retention. Specifically, the impact of negative affect on customer retention in the low customer inertia group (βNA-customer retention = − 0.186, p < 0.05) was significantly higher than in the high customer inertia group (βNA-customer retention = 0.054, p > 0.05) (∆χ2 [1] = 4.457, p < 0.05). That is, when policy holders perceive that, compared with the existing health plan, there are many other health plans that fulfill their specific needs and that they are too indifferent to change. The indifference to find a better financial alternative determines policy holders desire to continue with service provider, even they have negative affective service experiences. Insurance companies should improve service quality elements (i.e., number of hospital empanelment, policy coverage, across the country accessibility of the plan, cashless options, serviceability) so that switching to other service provider does not appear relevant. Such endeavors would ultimately support existing policy holders believe that seeking a better insurance plan would be cumbersome in terms of time and effort consuming, thereby encouraging them to stay with the current insurance company.

The descriptive statistical analysis presented that respondent within high customer inertia group positively unveiled a higher willingness to remain with the current insurance company (mean = 6.488) than those within the low customer inertia group (mean = 5.627). Furthermore, it is interesting to note that more male respondents (51.8%) than female respondents (48.2%) were within the high customer inertia group. Respondents within the low customer inertia group were more highly educated (77.4%) with university/graduate degrees than those within high customer inertia group (70.6%) with university/graduate degrees. So in order to confirm that whether the male respondents (high customer inertia) and highly educated respondents (low customer inertia) express inertia differently, we conducted the independent sample t tests. The results revealed that the t values were significant at the 0.01 level. The findings related to difference between two customer inertia groups, could help health insurance companies to make distinctive marketing strategies for the retention of policyholders with high and low customer inertia, respectively. Any form of customer inertia is not good for the policy holders as well as health insurance companies thus consumer awareness campaigns should be launched in order to facilitate better informed decisions regarding policy renewal.

Managerial implications

In a firmly competitive environment like insurance, gaining repeat business by retaining existing customers seems to be a requirement for any financial services company survival (Chen and Wang 2009; Williams and Williams 2015). In this research, we tried to develop a better understanding of the customer retention process. The theoretical framework developed in an insurance setting adequately and successfully explained a total variance in customer retention. Customer retention has long been considered as a powerful force influencing insurance service business success (Ansell et al. 2007). The findings would facilitate insurance companies in building retention strategies by trying to identify inertia or disinterest factors. It is also important to distinguish inertia from satisfaction. Insurance firms should try to interact with their customers in order to understand their reasons for continuing the firm. The behavioral factors need to differentiated from service-related factors. This would help in focusing on improving the service quality elements.

A close investigation was conducted to comprehend the comparative total impact of insurance company reputation, insurance service performance, and positive and negative affect on customer retention. As described earlier, the magnitude of standardized coefficients, positive affect emerged as the most critical contributor to customer retention in the insurance sector, followed by the insurance service performance, company reputation, and negative affect at the last. Distinguishing this prominent role of positive affect, insurance marketing practitioners must employ potential monetary and non-monetary means to elicit customers’ positive affective experiences. Ramamoorthy et al.’s (2018) indicated that service quality (e.g., reliability and responsiveness) are key factors that effectively evoke insurance customers’ affective/satisfaction evaluation. The role of such factors on positive behavioral intentions becomes more vital for repeat customers compared to first-time insurance purchasers. It would be important for insurance companies to focus on the service quality elements to improve customers’ positive affect, which would eventually lead to the lift in customer retention.

The loss aversion put together into the prospect theory postulates that the outcome of one’s perceived losses tends to be more eminent than the impact of his/her perceived gains (Einhorn and Hogarth 1981; Slovic et al. 1977). In other words, insurance customers’ negative affect derived from unpleasant or unfavorable service experiences would have a greater impact on retention than positive affect. Thus, in the highly subject to solicited business like health insurance, the companies cannot afford to take risk as far as the service performance is concerned. In contrast, our empirical results from the structural analysis specified the greater impact of positive affect on customer retention than negative affect, which may be ascribed to the multidimensional nature of insurance service (Jayasimha and Murugaiah 2008). Although not in line with Einhorn and Hogarth (1981), the findings are in tandem with research assertion that positive experiences under certain situations/conditions generate a stronger customer response than negative experiences (Kautish and Rastogi 2008; Oliver 1992; Westbrook and Oliver 1991). The recent developments in building relationships and delivering quality service has focused on the beneficial effects of customer retention. It is often argued that customer attraction costs are higher than retention costs in services (Eisingerich and Bell 2006; Ennew and Binks 1996). Thus, marketing strategies focused on customer inertia is unlikely to be sustainable in the long term which can be explored by incorporating the marketing analytics framework in the model. However, firms having customers who feel succumbed to other providers are likely to lead to negative word of mouth, less ability to cross-sell, lower acceptance of new products, and other negative outcomes associated with customer defection (Colgate and Lang 2001, p. 343).

Limitations and future research imperatives

Alike any other service research, the present study also holds some limitations that propose future research avenues. First, the research has not examined the impact of demographic factors, e.g., age, income, occupation, and marital status in the conceptual model which may have shown significant differences in the marketing analytics-oriented results. The price comparison has been highlighted as significant factor for service organizations in view of ‘de-locating’ their offerings by utilizing the Internet facility (East et al. 2012). Thus, testing the role of these factors in the marketing model statistics and analytics would be a critical extension of the present study. Second, the data were collected from health policy holders from one insurance company through questionnaire-based survey only. While it has the advantage to get the information from the real customers at the same time if we have included policy holders from different companies it would have provided a better comparative assessment of their insurance service experiences. Future research may collect consumer choice-based data from a few more insurance companies and then compare the marketing relationships of the research variables. Indian life and medical insurance is governed by inertia not only because of difficulty in evaluating service dimensions, but also by lack of awareness and commitment toward health issues. This behavior is further augmented by poor focus of government toward health services, inability to provide medical facilities and medical staff in the small cities and villages, and regular medical checkups being considered as futile practice. The perception toward investment on regular health checkups and monitoring systems are unheard of in Indian context. Thus, inertia maybe seen as a resultant of social, cultural, and economic conditions that play a critical role in conditioning people’s behavior toward health insurance. Future study may be directed to understand the role of these factors along with the psychological factors on consumers’ attitude toward health insurance. This study is restricted to the exploration of the influence of insurance company reputation, insurance service performance, positive and negative affects, and their impact on customer retention with moderation of customer inertia. In the future, in light of the differentiated insurance services offered by the companies, the reconsideration of the relationships between the aforesaid constructs is a topic worthy to be researched. Lastly, it is observable that this research employs cross-sectional data to test the hypotheses; thus, longitudinal data may provide better understanding of the entire health insurance market. In addition, in the future studies, the health insurance policy implications with respect to COVID-19 pandemic situation can also be explored keeping in mind the customer inertia and customer retention aspects.

References

Abdelfattah, F.A., M.S. Rahman, and M. Osman. 2015. Assessing the antecedents of customer loyalty on healthcare insurance products: Service quality; perceived value embedded model. Journal of Industrial Engineering and Management 8 (5): 1639–1660.

Abu-Salim, T., O.P. Onyia, T. Harrison, and V. Lindsay. 2017. Effects of perceived cost, service quality, and customer satisfaction on health insurance service continuance. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 22 (4): 173–186.

Ahlin, T., M. Nichter, and G. Pillai. 2015. Health insurance in India: What do we know and why is ethnographic research needed. Anthropology and Medicine 23 (1): 102–124.

Al-Weshah, G.A. 2017. Marketing intelligence and customer relationships: Empirical evidence from Jordanian banks. Journal of Marketing Analytics 5 (3–4): 153–162.

Amoroso, D., and R. Lim. 2017. The mediating effects of habit on continuance intention. International Journal of Information Management 37 (6): 693–702.

Andreassen, T.W., and B. Lindestad. 1998a. The effect of corporate image in the formation of customer loyalty. Journal of Service Research 1 (1): 82–92.

Andreassen, T.W., and B. Lindestad. 1998b. Customer loyalty and complex services: The impact of corporate image on quality, customer satisfaction and loyalty for customers with varying degree of service expertise. International Journal of Service Industry Management 9 (1): 7–23.

Ansell, J., T. Harrison, and T. Archibald. 2007. Identifying cross-selling opportunities, using lifestyle segmentation and survival analysis. Marketing Intelligence and Planning 25 (4): 394–410.

Armstrong, J.C., and T.S. Overton. 1977. Estimating non-response bias in mail surveys. Journal of Marketing Research 14 (3): 396–402.

Assael, H. 1998. Consumer Behavior and Marketing Action. Cincinnati, OH: Southwestern College Publishing.

Auger, P., T. Devinney, G. Dowling, and C. Eckert. 2016. Inertia and discounting in the selection of socially responsible investments: An experimental investigation. Annals in Social Responsibility 2 (1): 29–47.

Bansal, H.P., G. Irving, and S.F. Taylor. 2004. A three-component model of customer commitment to service providers. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 32 (3): 234–250.

Bansal, H.P., G. Irving, and S.F. Taylor. 2005. Migrating to new service providers: Toward a unifying framework of consumers’ switching behaviors. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 33 (1): 96–115.

Bansal, H.S., and S.F. Taylor. 1999. The service provider switching model (SPSM): A model of consumer switching behavior in the services industry. Journal of Service Research 2 (2): 200–218.

Barnes, W., M. Gartland, and M. Stack. 2004. Old habits die hard: Path dependency and behavioral lock-in. Journal of Economic Issues 38 (2): 371–377.

Barroso, C., and A. Picón. 2012. Multi-dimensional analysis of perceived switching costs. Industrial Marketing Management 41 (3): 531–543.

Bartikowski, B., and G. Walsh. 2011. Investigating mediators between corporate reputation and customer citizenship behaviours. Journal of Business Research 64 (1): 39–44.

Bartikowski, B., G. Walsh, and S.E. Beatty. 2011. Culture and age as moderators in the corporate reputation and loyalty relationship. Journal of Business Research 64 (9): 966–972.

Barwitz, N. 2020. The relevance of interaction choice: Customer preferences and willingness to pay. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 53, 101953.

Bawa, K. 1990. Modelling inertia and variety seeking tendencies in brand choice behavior. Marketing Science 9 (3): 263–278.

Bell, S., S. Auh, and K. Smalley. 2005. Customer relationship dynamics: Service quality and customer loyalty in the context of varying levels of customer expertise and switching costs. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 33 (2): 169–183.

Berger, L.A., P. Kleindorfer, and H. Kunreuther. 1989. A dynamic model of the transmission of price information in auto insurance markets. Journal of Risk and Insurance 56 (1): 17–33.

Bodet, G. 2008. Customer satisfaction and loyalty in service: Two concepts, four constructs, several relationships. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 15 (3): 156–162.

Bougie, R., R. Pieters, and M. Zeelenberg. 2003. Angry customers don’t come back, they get back: The experience and behavioral implications of anger and dissatisfaction in services. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 31 (4): 377–393.

Boyle, E. 1996. An experiment in changing corporate image in the financial services industry in the UK. Journal of Services Marketing 10 (4): 56–69.

Bozzo, C. 2002. Understanding inertia in an industrial context. Journal of Customer Behavior 1 (3): 335–355.

Burnham, T.A., J.K. Frels, and V. Mahajan. 2003. Consumer switching costs: A typology, antecedents, and consequences. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 31 (2): 109–126.

Carter, L., D. Gray, S. D’Alessandro, and L. Johnson. 2016. The “I love to hate them” relationship with cell phone service providers: The role of customer inertia and anger. Services Marketing Quarterly 37 (4): 225–240.

Chakrabarti, A., and A. Shankar. 2015. Determinants of health insurance penetration in India: An empirical analysis. Oxford Development Studies 43 (3): 379–401.

Chen, M.-F., and L.-H. Wang. 2009. The moderating role of switching barriers on customer loyalty in the life insurance industry. The Service Industries Journal 29 (8): 1105–1123.

Christiansen, M.C., M. Eling, J.P. Schmidt, and L. Zirkelbach. 2016. Who is changing health insurance coverage? Empirical evidence on policy holder dynamics. Journal of Risk and Insurance 83 (2): 269–300.

Chun, R. 2005. Corporate reputation: Meaning and measurement. International Journal of Management Reviews 7 (2): 91–109.

Colgate, M., and R. Hedge. 2001. An investigation into the switching process in retail banking services. International Journal of Bank Marketing 19 (5): 201–212.

Colgate, M., and B. Lang. 2001. Switching barriers in consumer markets: An investigation of the financial services industry. Journal of Consumer Marketing 18 (4): 332–347.

Crosby, A., and N. Stephens. 1987. Effect of relationship marketing on satisfaction, retention, and prices in the life insurance industry. Journal of Marketing Research 24 (4): 404–411.

Danaher, T.S., and M.E. David. 2012. Uncovering the real effect of switching costs on the satisfaction-loyalty association: The critical role of involvement and relationship benefits. European Journal of Marketing 46 (3): 447–468.

De Matos, A.C., L.J. Henrique, and F. De Rosa. 2013. Customer reactions to service failure and recovery in the banking industry: The influence of switching costs. Journal of Services Marketing 27 (7): 526–538.

Devlin, J.F. 1997. Adding value to retail financial services. Journal of Marketing Practice: Applied Marketing Science 3 (4): 251–267.

Dick, A., and K. Basu. 1994. Customer loyalty: Towards an integrated conceptual framework. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 22 (2): 99–113.

Diener, E., R.J. Larsen, S. Levine, and R.A. Emmons. 1985. Intensity and frequency: Dimensions underlying positive and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 48 (5): 1253–1265.

Dominique-Ferreira, S. 2017. How important is the strategic order of product attribute presentation in the non-life insurance market? Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 34: 138–144.

Dowling, G.R. 2004. Corporate reputations: Should you compete on yours. California Management Review 46 (3): 19–36.

Dragos, S.L. 2014. Life and non-life insurance demand: The different effects of influence factors in emerging countries from Europe and Asia. Economic Research- Ekonomska Istraživanja 27 (1): 169–180.

Dror, D.M., R. Radermacher, and R. Koren. 2007. Willingness to pay for health insurance among rural and poor persons: Field evidence from seven micro health insurance units in India. Health Policy 82 (1): 12–27.

East, R., U. Grandcolas, et al. 2012. Reasons for switching service providers. Australasian Marketing Journal 20 (2): 164–170.

Einhorn, H.J., and R.M. Hogarth. 1981. Behavioral decision theory: Processes of judgment and choice. Annual Review of Psychology 32: 53–88.

Eisingerich, A.B., and S.J. Bell. 2006. Relationship marketing in the financial services industry: The importance of customer education, participation and problem management for customer loyalty. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 10 (4): 86–97.

Ennew, C., and M. Binks. 1996. The impact of service quality and service characteristics on customer retention: Small businesses and their banks in the UK. British Journal of Management 7 (3): 219–230.

ET. 2019. Should you port your health insurance policy? Retrived December 21, 2020 from https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/wealth/insure/should-you-port-your-health-insurance-policy/articleshow/67851423.cms?utm_source=contentofinterestandutm_medium=textandutm_campaign=cppst.

ET. 2020. How Covid-19 is changing the Health Insurance Market in India. Retrived November 28, 2020 from https://health.economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/insurance/how-covid-19-is-changing-the-health-insurance-market-in-india/77634563.

FE. 2020. How Covid-19 may impact health insurance industry in India. Retrived November 18, 2020 from https://www.financialexpress.com/money/insurance/how-covid-19-may-impact-health-insurance-industry-in-india/1994426/.

Fernandes, T., and T. Pinto. 2019. Relationship quality determinants and outcomes in retail banking services: The role of customer experience. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 50: 30–41.

Folkman, S. 1997. Positive psychological states and coping with severe stress. Social Science and Medicine 45 (8): 1207–1221.

Folkman, S., and J.T. Moskowitz. 2000. Positive affect and the other side of coping. American Psychologist 55 (6): 647–654.

Fombrun, C.J. 1996. Reputation: Realizing Value from the Corporate Image. Boston: Harvard Business School Press.

Fombrun, C.J., N.A. Gardberg, and J.W. Sever. 2000. The reputation quotientSM: A multi-stakeholder measure of corporate reputation. Journal of Brand Management 7 (4): 241–255.

Fombrun, C.J., and M. Shaney. 1990. What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academy of Management Journal 33 (2): 233–258.

Fornell, C., and M.D. Johnson. 1993. Differentiation as a basis for explaining customer satisfaction across industries. Journal of Economic Psychology 14 (4): 681–696.

Fornell, C., and D.F. Larcker. 1981. Evaluating structural equation modeling with unobserved variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research 18 (1): 39–50.

Gambhir, R.S., R. Malhi, S. Khosla, R. Singh, A. Bhardwaj, and M. Kumar. 2019. Out-patient coverage: Private sector insurance in India. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care 8 (3): 788–792.

Ganesh, J., M.J. Arnold, and K.E. Reynolds. 2000. Understanding the customer base of service providers: An examination of the differences between switchers and stayers. Journal of Marketing 64 (3): 65–87.

Ghose, S., and O. Lowengart. 2013. Consumer choice and preference for brand categories. Journal of Marketing Analytics 1 (1): 3–17.

Gough, O., and P.D. Sozou. 2005. Pensions and retirement saving: Cluster analysis of consumer behavior and attitudes. International Journal of Bank Marketing 23 (7): 558–570.

Gray, D.M., S. D’Alessandro, L.W. Johnson, and L. Carter. 2017. Inertia in services: Causes and consequences for switching. Journal of Services Marketing 31 (6): 485–498.

Greenfield, H.I. 2005. Consumer inertia: A missing link. The American Journal of Economics and Sociology 64 (4): 1085–1089.

Gremler, D.D., and S.W. Brown. 1996. Service loyalty: Its nature, importance and implications. In Advancing Service Quality: A Global Perspective, ed. B. Edwardson, S.W. Brown, and R. Johnston, 171–180. International Service Quality Association.

Gremler, D.D., Y.V. Vaerenbergh, E.C. Brüggen, and K.P. Gwinner. 2020. Understanding and managing customer relational benefits in services: A meta-analysis. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 48 (3): 565–583.

Guinea, A.O. de and Markus, M.L. 2009. Why break the habit of a lifetime? Rethinking the roles of intention, habit, and emotion in continuing information technology use. MIS Quarterly 33 (3): 433–444.

Gupta, H. 2007. The role of insurance in health care management in India. International Journal of Health Care Quality Assurance 20 (5): 379–391.

Hair, J.F., Jr., W.C. Black, B.J. Babin, and R.E. Anderson. 2014. Multivariate Data Analysis, 6th ed. New Delhi: Pearson Education.

Handel, B.R. 2013. Adverse selection and inertia in health insurance markets: When nudging hurts. American Economic Review 103 (7): 2643–2682.

Handel, B.R., and J.T. Kolstad. 2015. Health insurance for “humans”: Information frictions, plan choice, and consumer welfare. American Economic Review 105 (8): 2449–2500.

Harrison, T. 2000. Financial Services Marketing. Pearson Education, Financial Times.

Harrison, T., and J. Ansell. 2002. Customer retention in the insurance industry: Using survival analysis to predict cross-selling opportunities. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 6 (3): 229–239.

Heckl, D., J. Mooxrmann, and M. Rosemann. 2010. Uptake and success factors of Six Sigma in the financial services industry. Business Process Management Journal 16 (3): 436–472.

Hellier, P.K., G.M. Geursen, R.A. Carr, and J.A. Rickard. 2003. Customer repurchase intention: A general structural equation model. European Journal of Marketing 37 (11/12): 1762–1800.

Hu, T.-I., and A. Tracogna. 2020. Multichannel customer journeys and their determinants: Evidence from motor insurance. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 54: 102022.

Huang, M.H., and S. Yu. 1999. Are consumers inherently or situationally brand-loyal? A set intercorrelation account for conscious brand loyalty and nonconscious inertia. Psychology and Marketing 16 (6): 523–544.

IRDAI. 2020. Guidelines on Standardization of General Terms and Clauses in Health Insurance Policy Contracts. Retrived December 20, 2020 from https://www.irdai.gov.in/ADMINCMS/cms/whatsNew_Layout.aspx?page=PageNo4157andflag=1.

Jayasimha, K.R., and V. Murugaiah. 2008. Service failure and recovery: Insurance sector. SCMS Journal of Indian Management 10 (12): 83–91.

Jones, M.A., D.L. Mothersbaugh, and S.E. Beatty. 2000. Switching barriers and repurchase intentions in services. Journal of Retailing 76 (2): 259–274.

Jones, M.A., D.L. Mothersbaugh, and S.E. Beatty. 2002. Why customer stay: Measure the underlying dimensions of services switching costs and managing their differential strategic outcomes. Journal of Business Research 55 (6): 441–450.

Jones, M.A., K.E. Reynolds, D.L. Mothersbaugh, and S.E. Beatty. 2007. The positive and negative effects of switching costs on relational outcomes. Journal of Service Research 9 (4): 335–355.

Kahneman, D., J.L. Knetsch, and R.H. Thaler. 1991. Anomalies the endowment effect, loss aversion, and status quo bias. Journal of Economic Perspectives 5 (1): 193–206.

Kahneman, D., and A. Tversky. 1979. Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica 47 (2): 263–292.

Kannadhasan, M. 2015. Retail investors’ financial risk tolerance and their risk-taking behaviour: The role of demographics as differentiating and classifying factors. IIMB Management Review 27 (3): 175–184.

Kautish, P., and M. Rastogi. 2008. Health care and service quality: Does the twain meet. Indian Journal of Public Enterprise 23 (44): 104–117.

Keaveney, S.M. 1995. Customer switching behavior in service industries: An exploratory study. Journal of Marketing 59 (2): 71–82.

Khare, A., S. Dixit, R. Chaudhary, P. Kochhar, and S. Mishra. 2012. Customer behavior toward online insurance services in India. Journal of Database Marketing and Customer Strategy Management 19 (2): 120–133.

Klemperer, P. 1995. Competition when consumers have switching costs: An overview with applications to industrial organization, macroeconomics, and international trade. Review of Economic Studies 62 (4): 515–539.

Kuo, R.-Z. 2020. Why do people switch mobile payment service platforms? An empirical study in Taiwan. Technology in Society 62: 101312.

Lai, L.-H., C.-T. Liu, and J.-T. Lin. 2011. The moderating effects of switching costs and inertia on the customer satisfaction retention link: Auto liability insurance service in Taiwan. Insurance Markets and Companies 2 (1): 69–78.

Lam, S.Y., V. Shankar, M.K. Erramilli, and B. Murthy. 2004. Customer value, satisfaction, loyalty, and switching costs: An illustration from a business-to-business service context. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 32 (3): 293–311.

Lee, C.-Y. 2019. Does corporate social responsibility influence customer loyalty in the Taiwan insurance sector? The role of corporate image and customer satisfaction. Journal of Promotion Management 25 (1): 43–64.

Lee, K., and K. Joshi. 2017. Examining the use of status quo bias perspective in IS research: Need for re-conceptualizing and incorporating biases. Information Systems Journal 27 (6): 733–752.

Lee, J., J. Lee, and L. Feick. 2001. The impact of switching costs on the customer satisfaction-loyalty link: Mobile phone service in France. Journal of Service Marketing 15 (1): 35–48.

Lee, R., and L. Neale. 2012. Interactions and consequences of inertia and switching costs. Journal of Services Marketing 26 (5): 365–374.

Li, C.-Y. 2015. Switching barriers and customer retention: Why customers dissatisfied with online service recovery remain loyal. Journal of Service Theory and Practice 25 (4): 370–393.

Macintosh, G. 2009. Examining the antecedents of trust and rapport in services: Discovering new interrelationships. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 16 (4): 298–305.

Mani, Z., and I. Chouk. 2018. Consumer resistance to innovation in services: Challenges and barriers in the internet of things era. Journal of Product Innovation Management 35 (5): 780–807.

Mano, H. and Oliver, R.L. 1993. Assessing the dimensionality and structure of the consumption experience: Evaluation, feeling, and satisfaction. Journal of Consumer Research 20 (3): 451–466.

Marsh, H.W., and D. Hocevar. 1988. A new, more powerful approach to multitrait-multimethod analyses: Application of second-order confirmatory factor analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology 73 (1): 107–117.

Marshall, C.E. 1985. Can we be consumer-oriented in a changing financial service world? Journal of Consumer Marketing 2 (4): 37–43.

Masatlioglu, Y., and E.A. Ok. 2005. Rational choice with status quo bias. Journal of Economic Theory 121 (1): 1–29.

Meesala, A., and J. Paul. 2018. Service quality, consumer satisfaction and loyalty in hospitals: Thinking for the future. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 40: 261–269.

Meidan, A. 1996. Marketing Financial Services. Houndmills: MacMillan Press.

Michielsen, J., B. Criel, N. Devadasan, W. Soors, E. Wouters, and H. Meulemans. 2011. Can health insurance improve access to quality care for the Indian poor? International Journal for Quality in Healthcare 23 (4): 471–486.

Milner, T., and D. Rosenstreich. 2013. A review of consumer decision making models and development of a new model for financial services. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 18 (2): 106–120.

Mittal, B., and W.M. Lassar. 1998. Why customers switch? The dynamics of satisfaction versus loyalty. Journal of Services Marketing 12 (3): 177–194.

Nguyen, N. 2010. Competence and benevolence of contact personnel in the perceived corporate reputation: An empirical study in financial services. Corporate Reputation Review 12 (4): 345–356.

Nguyen, N., and G. LeBlanc. 1998. The mediating role of corporate image on customers’ retention decisions: An investigation in financial services. International Journal of Bank Marketing 16 (2): 52–65.

Nguyen, N., and G. LeBlanc. 2001. Corporate image and corporate reputation in customers’ retention decisions in services. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 8 (4): 227–236.

Nguyen, N., and G. LeBlanc. 2002. Contact personnel, physical environment and the perceived corporate image of intangible services by new clients. International Journal of Service Industry Management 13 (3): 242–262.

Nienaber, A.-M., M. Hofeditz, and R.H. Searle. 2014. Do we bank on regulation or reputation? A meta-analysis and meta-regression of organizational trust in the financial services sector. International Journal of Bank Marketing 32 (5): 367–407.

Oliver, R.L. 1992. An investigation of the attribute basis of emotion and related affects in consumption. Advances in Consumer Research 19 (1): 237–244.

Oliver, R.L. 1993. Cognitive, affective, and attribute bases of the satisfaction response. Journal of Consumer Research 20 (3): 418–430.

Oliver, R.L. 1997. Satisfaction: A Behavioral Perspective On The Consumer. New York: McGraw Hill.

Oliver, R.L. 1999. Whence customer loyalty? Journal of Marketing 63 (4): 33–44.

Oliver, R.L., and J.E. Swan. 1989. Consumer perceptions of interpersonal equity and satisfaction in transaction: A field survey approach. Journal of Marketing 53 (2): 21–35.

Ortony, A., G.L. Clore, and A. Collins. 1988. The Cognitive Structure of Emotions. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Page, G., and H. Fearn. 2005. Corporate reputation: What do consumers really care about? Journal of Advertising Research 45 (3): 305–313.

Panda, P., A. Chakraborty, W. Raza, and A.S. Bedi. 2016. Renewing membership in three community-based health insurance schemes in rural India. Health Policy and Planning 31 (10): 1433–1444.

Panther, T., and J.D. Farquhar. 2004. Consumer responses to dissatisfaction with financial service providers: An exploration of why some stay while others switch. Journal of Financial Services Marketing 8 (4): 343–353.

Patterson, P.G., and T. Smith. 2003. A cross-cultural study of switching barriers and propensity to stay with service providers. Journal of Retailing 79 (2): 107–120.

Pickett, S., E. Marks, and V. Ho. 2017. Gain in insurance coverage and residual uninsurance under the Affordable Care Act: Taxas, 2013–2016. American Journal of Public Health 107 (1): 120–126.

Picón, A., I. Castro, and J.L. Roldán. 2014. The relationship between satisfaction and loyalty: A mediator analysis. Journal of Business Research 67 (5): 746–751.

Plutchik, R. 2003. Emotions and Life: Perspectives from Psychology, Biology and Evolution. Baltimore, MD: United Book Press.

Polites, G., and E. Karahanna. 2012. Shackled to the status quo: The inhibiting effects of incumbent system habit, switching costs, and inertia on new system Acceptance dark side of reviews view project research methods view project. MIS Quarterly 36 (1): 21–42.

Posey, L., and S. Tennyson. 1998. The coexistence of distribution systems under price search: Theory and some evidence from insurance. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 35 (1): 95–115.

Posey, L., and A. Yavas. 1995. A search model of marketing systems in property-liability insurance. Journal of Risk and Insurance 62 (4): 666–689.

PwC. 2020. Health Insurance Consumer Pulse Survey. Retrived December 12, 2020 from https://www.pwc.in/assets/pdfs/healthcare/health-insurance-consumer-pulse-survey.pdf.

Rahman, M.S., F.A.M.A. Fattah, M. Zaman, and H. Hassan. 2018. Customer’s patronage decision toward health insurance products: Mediation and multi-group moderation analysis. Asia Pacific Journal of Marketing and Logistics 30 (1): 62–83.

Ramamoorthy, R., A. Gunasekaran, M. Roy, B.K. Rai, and S.A. Senthilkumar. 2018. Service quality and its impact on customers’ behavioral intentions and satisfaction: An empirical study of the Indian life insurance sector. Total Quality Management and Business Excellence 29 (7/8): 834–847.

Ranaweera, C., and J. Prabhu. 2003. The influence of satisfaction and trust and switching barriers on customer retention in a continuous purchasing setting. International Journal of Service Industry Measurement 14 (4): 374–395.

Robson, J., and Y. Sekhon. 2011. Addressing the research needs of the insurance sector”. International Journal of Bank Marketing 29 (7): 512–516.

Rundle-Thiele, S. 2005. Exploring loyal qualities: Assessing survey-based loyalty measures. Journal of Services Marketing 19 (7): 492–500.

de Ruyter, K., J.M. Bloemer, and M.G. Wetzels. 1998. On the relationship between perceived service quality, service loyalty and switching costs. International Journal of Service Industry Management 9 (5): 436–453.

Samuelson, W., and R. Zeckhauser. 1988. Status quo bias in decision making. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty 1 (1): 7–59.

Satorra, A., and P.M. Bentler. 2001. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika 66 (4): 507–514.

Schlesinger, H., and J.M. Schulenburg. 1991. Search costs, switching costs and product heterogeneity in an insurance market. Journal of Risk and Insurance 58 (1): 109–119.

Schlesinger, H., and J.M. Schulenburg. 1993. Consumer information and decision to switch insurers. Journal of Risk and Insurance 60 (1): 109–119.

Schwarz, G.M. 2012. The logic of deliberate structural inertia. Journal of Management 38 (2): 547–572.

Sen, A., J. Pickett, and L.R. Burns. 2014. The health insurance sector in India: History and opportunities. In India’s Healthcare Industry: Innovation in Delivery, Financing, and Manufacturing, (Eds.) L.R. Burns, (pp. 361–399), New Delhi: Cambridge University Press.

Seth, H., S. Talwar, A. Bhatia, A. Saxena, and A. Dhir. 2020. Consumer resistance and inertia of retail investors: Development of the resistance adoption inertia continuance (RAIC) framework. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 55: 102071.

Sharma, N., and P.G. Patterson. 2000. Switching costs, alternative attractiveness and experience as moderators of relationship commitment in professional, consumer services. International Journal of Service Industry Management 11 (5): 470–490.

Siddiqui, M.H., and T.G. Sharma. 2010. Analyzing customer satisfaction with service quality in life insurance services. Journal of Targeting, Measurement and Analysis for Marketing 18 (3/4): 221–238.

Slovic, P., B. Fischhoff, and S. Lichtenstein. 1977. Behavioral decision theory. Annual Review of Psychology 28: 1–39.

Smith, K.A., R.J. Willis, and M. Brooks. 2000. An analysis of customer retention and insurance claim patterns using data mining: A case study. Journal of the Operational Research Society 51 (5): 532–541.