Abstract

This article deals with the increasing computerization of the financial markets and the consequences of such process on our ability to collect information about financial prices. The concept of information is at the heart of financial economics simply because this notion is a precondition for all investments. Since financial prices characterize an agreement on a transaction between two counterparties, they understandably became a key informational indicator for decision. This article will analyse the increasing computerization of financial sphere by discussing the recent emergence of what is called a “flash crash” and its impact on the traditional ways of collecting information in finance (technical analysis, fundamental analysis and statistical approach). I argue that the growing computerization of financial markets generated a “hyper-reality” in which financial prices do not refer to “something” anymore implying a revision of our usual way of defining/using the notion of information.

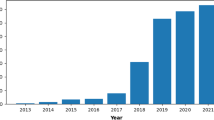

Source The Economist (25 February 2013).

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Abarbanell, J. and Bushee, B. (1997). Fundamental Analysis, Future Earnings and Stock Prices. Journal of Accounting Research, 35(1), 1–24.

Allen, F. (1999) The role of information in financial and capital markets, Working paper, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania.

Aoki, M. and Hiroshi, Y. (2007). A Stochastic Approach to Macroeconomics and Financial Markets. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Arvidsson, A. (2009). The Ethical Economy: Towards a post-capitalist theory of value. New Left Review, 97, 13–29.

Baldwin, J. (2015). Baudrillard and Neoliberalism. International Journal of Baudrillard Studies, 12(2), 1705–6411.

Balwin, J. (2012). Financial Crash and Hyper Real Economy. Williamsburg: Books Division.

Baudrillard, J. (1968). Le système des objets. Paris: Gallimard.

Baudrillard, J. (1994). Simulacra and Simulation, translated by Sheila Faria Glaser. Michigan: The University of Michigan Press.

Bay, T. and Schinckus, C. (2012). Critical Finance Studies: An interdisciplinary perspective. Journal of Interdisciplinary Economics, 24, 1–6.

Belze, L. and Spieser, P. (2005). Histoire de la finance. Paris: Vuibert.

Bernstein, P. (1992). Capital Ideas : The improbable origins of modern Wall Street. New York and Toronto: Free Press, Maxwell Macmillan Canada, Maxwell Macmillan International.

Black, F. (1971). Toward a Fully Automated Stock Exchange. Financial Analysts Journal, 27(4), 28–35.

Bulkowski, T. (2005). Encyclopedia of Chart Patterns. New York: Wiley.

Cartwright, N. (1999). The Dappled World: a study of the boundaries of science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Chane-Alune, E. (2006). Accounting Standardization and Gouvernance Structures, Working paper no 0609, Liège: University of Liège

Colander, D., Follmer, H., Haas, A., Godber, M., Juselius, K., Kirman, A., et al. (2009). The Financial Crisis and the Systemic Failure of Academic Finance. Critical Review: A Journal of Politics and Society, 21(2–3), 249–267.

Committee on the Global Financial System (2001). The Implications of Electronic Trading in Financial Markets. BIS (Bank for International Settlements), Paper 12.

Cootner, P. H. (1964). The Random Character of Stock Market Prices. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Cornell, B., and Rutten, J. (2006). Market Efficiency, Crashes and Securities Litigation, 81 Tulane. Law Review, 443, 443.

Dupuy, J.-P. (1992). Libéralisme et Justice sociale : le sacrifice et l’envie. Paris: Hachette.

Durkheim E. (1975 [1908]), Éléments d’une théorie sociale, Paris: Les Éditions de Minuit, coll. Le sens commun.

Engle, R. and Russell, J. (2004). Analysis of High Frequency Financial Data. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Fama, E. (1965). The Behavior of Stock-Market Prices. Journal of Business, 38(1), 34–105.

Fourcade, M. and Khurana, R. (2009). From Social Control to Financial Economics: The linked ecologies of economics and business in twentieth-century America. Annual Meeting of the SASE Annual Conference, Paris.

Frankfurter, G. and McGoun, E. (1996). The Methodology of Finance: What it is and what it can be. London: JAI Press.

Frankfurter, G. M. and McGoun, E. G. (1999). Ideology and the Theory of Financial Economics. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organisation, 39, 159–177.

Galison, P. (1997). Image and Logic: A material culture of microphysics. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Gann, W. (1923). Truth of the Stock Tape: A study of the stock and commodity markets with charts and rules for successful trading and investing. London: Financial guardian Publishing Company.

Hamilton, W. D. (1922). The Stock Market Barometer. New York: Harper.

Hertz, E. (2000). Stock Markets as simulacra. Tsantsa, 5, 40–50.

Hoffland, D. (1967). The Folklore of Wall Street. Financial Analysts Journal, 23(3), 85–97.

Jiang, G., Tang, N., Law, E., (2002). Electronic Trading in Hong Kong and its Impact on Market Functioning. BIS (Bank for International Settlements) Papers 12.

Jovanovic, F. (2001). Pourquoi l’hypothèse de marche aléatoire en théorie financière? Les raisons historiques d’un choix éthique. Revue d’Economie Financière, 61, 203–211.

Jovanovic, F. (2008). The Construction of the Canonical History of Financial economics. History of Political Economy, 40(2), 213–242.

Jovanovic, F. (2009), L’institutionnalisation de l’économie financière : Perspectives historiques. Vol. 20: Revue d’Histoire des Sciences Humaines.

Karl, A. (2013). Bank Talk: performativity and financial markets. Journal of Cultural Economy, 6(1), 61–77.

Keynes, J. M. (1937). The General Theory of Employment. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 51(2), 209–223.

Kindleberger, C. (1989). Manias, Panics, and Crashes: A history of financial crises. London: Macmillan.

Kothari, S. P., Lester, R. (2012). The Role of Accounting in the Financial Crisis: Lessons for the future. Accounting Horizons, 26(2), 335–351.

Lagoarde-Segot, T. (2016). Financialization: towards a new research agenda, International Review of Financial Analysis.

Latour, B. (1987). Science in Action: How to follow scientists and engineers through society. Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Laux, C. and Leuz, C. (2010). Did Fair-Value Accounting Contribute to the Financial Crisis? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 24, 93–118.

Leigh, S. (2002). Essential Technical Analysis: Tools and techniques to spot market trends. New York: Wiley.

Lépinay, V.-A. (2007). Decoding Finance. Articulation and Liquidity around a Trading Room. In D. MacKenzie, F. Muniesa, L. Siu (Eds.), Do Economists Make Markets? On the Performativity of Economics (pp. 87–127). Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Lépinay, V.-A. (2007). “Parasitic formulae: the case of capital guarantee products’s. In M. Callon, Y. Millo, F. Muniesa (Eds.), Market Devices. Oxford: Blackwell.

Lev, B. and Thiagarajan, R. (1993). Fundamental Information Analysis. Journal of Accounting Research, 31(2), 190–215.

Macintosh, N. B. (2003). From Rationality to Hyperreality: Paradigm poker. International Review of Financial Analysis, 12(4), 453–465.

Macintosh, N., Shearer, T., Thornton, D., and Welker, M. (2000). Accounting as Simulacrum and Hyperreality: Perspectives on income and capital. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 25(1), 13–50.

Mackenzie, D. (2006). An Engine, Not a Camera: How financial models shape markets. Cambridge: MIT Press.

MacKenzie, D., and Millo, Y. (2003). Constructing a Market, Performing Theory: The historical sociology of a financial derivatives exchange. American Journal of Sociology, 109(1), 107–145.

Madrigal, A. (2010). No Easy Tech Explanation for What Caused Wall St. ‘Flash Crash’, The Atlantic Magazine.

Markowitz, H. (1952). Portfolio Selection. Journal of Finance, 7(1), 77–91.

McGoun, E. (1997). Hyperreal Finance. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 8(1–2), 97–122.

Millo, Y. and MacKenzie, D. (2009). The Usefulness of Inaccurate Models: Towards an understanding of the emergence of financial risk management. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 34, 638–653.

Muniesa, F. (2000). Un Robot Walrasien. Cotation électronique et justesse de la découverte des prix. Politix, 13, 121–154.

Muniesa, F. (2007). Market Technologies and the Pragmatics of Prices. Economy and Society, 36(3), 377–395.

Muniesa, F. (2014). The Provoked Economy: Economic reality and the performative turn. London: Routledge.

Oberlechner, Th. (2001). Importance of Technical and Fundamental Analysis in the European Foreign Exchange Market. International Journal of Finance and Economics, 6, 81–93.

Orléan, A. (2008). Knowledge in Finance: Objective value versus convention. In Richard Arena Agnès Festré (Eds.), Handbook of Knowledge and Economics. Boston: Edward Elgar.

Park, C.H. and Irwin, S. (2004). The Profitability of Technical Analysis: A review, AgMas Research Paper, no 4, Champaign: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Poitras, G. (2000). The Early History of Financial Economics (pp. 1478–1776). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Poitras, G. (2009). From Antwerp to Chicago: The history of exchange traded derivative security contracts. Revue d’Histoire des Sciences Humaines, 20, 11–50.

Power, M. (2010). Fair Value Accounting, Financial Economics and the Transformation of Reliability. Accounting and Business Research, 40(3), 197–210.

Preda, A. (2009). Framing Finance. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Ramaswamy, M. (2006). On the Phenomenon of Information Dilution. Issues in Information Systems, 7(2), 289–292.

Rhea, R. (1932). Dow Theory. New York: Barrons.

Sajter, D. and Ćorić, T. (2009). (I)rationality of Investors on Croatian Stock Market, EFZG Working Papers Series 0901, Faculty of Economics and Business, University of Zagreb.

Salomon, G. (1979). The Interaction of Media, Cognition and Learning. San Fransisco: Jossey-Bass.

Schinckus, C. (2008). The Financial Simulacrum. Journal of Socio-Economics, 73(3), 1076–1089.

Schinckus, C. and Christiansen, I. (2012). “Visual Finance” (with I. Christiansen). Journal of Interdisciplinary Economics, 24, 173–194.

Schultz, H. (1925). Forecasting Security Prices. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 20(150), 244–249.

SEC (2010) U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (September 30, 2010). "Findings Regarding the Market Events of May 6, 2010". Archived from the original on 10 October 2010. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

Sewell, M. (2008). Technical Analysis, Working paper, University College, London.

Shiller, R. (2008). The Subprime Solution. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Shiller, R. (2012). Finance and the Good Society. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Stewart, I. (2012). 17 Equations that Changed the World. London: Profile Books.

Stiglitz, J. (2010). Freefall: America, free markets, and the sinking of the world economy. New York: W.W. Norton Company.

Tsang, R. (1999). Open outcry and electronic trading in futures exchanges. Bank of Canada Review, Spring.

Whitley, R. (1986). The Rise of Modern Finance Theory: Its characteristics as a scientific field and connection to the changing structure of capital markets. In W. J. Samuels (Ed.), Research in the History of Economic Thought and Methodology (pp. 147–178). Greenwich: JAI Press Inc.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Schinckus, C. An essay on financial information in the era of computerization. J Inf Technol 33, 9–18 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41265-016-0027-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41265-016-0027-1