Abstract

This article develops a framework to explain ideological diversity within political parties in parliamentary democracies from the positions of individual legislators. First, I review the different theories explaining the variation of ideological diversity within political parties in the field of party politics and legislative studies. Then, I propose to model the relations between legislators, their party and their constituents as a competitive delegation process building on the principal-agent theory. I draw on the literature on the distribution of power within political parties to argue that intra-party ideological diversity can best be explained by vertical bargains taking place between the different territorial layers of political parties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Political parties need to be cohesive enough to be able to stabilize their organization, to present a coherent manifesto, to form stable governments and to unite forces to be able to pass policies. At the same time, they must be diverse enough to represent the different voices of their constituency (Esther Herrmann 2017). In this regard, ideological diversity is key to the well being of democracies and the stability of political systems and governments. Yet, in times of increasing polarization, this balance proves difficult to find, which is expressed in difficulties to negotiate coalitions and policy, as well as in numerous party splits. In this context, scholars’ attention has been drawn to centrifugal tendencies within parliamentary parties: explaining why some parties are consistently more or less diverse than others seems more critical than ever.

An important amount of works therefore focuses on the existence and organization of diversity within political parties and how the latter come to create, maintain and sometimes impose unity among their ranks. The majority of these studies approach party cohesion through the lens of the voting behaviour of MPs in parliament. As a result, diversity is dichotomous—MPs either vote with their party (unity) or not (dissent)—and is only conceptualized with regards to the national level of political parties, leading to confusions between legislators’ ideological positions and their voting behaviour. Indeed, legislators may have a different position than the official party’s on a certain matter but still toe the line out of solidarity or out of fear of being sanctioned. Moreover, the same voting behaviour may respond to very different motivations: a dissenting vote, for example, may be the expression of dissent towards the party as whole, but may also reflect agreement towards another party’s subgroup with a particular ideological orientation. Party discipline, therefore, is a behavioural translation of the parties’ internal diversity, but the latter is worth a more direct examination and explanation.

This article draws attention to a neglected factor of ideological diversity: the existence of different territorial layers within parties. Ideological divergences, indeed, often follow territorial lines, especially in decentralized countries. For example, in Spain, the Socialist Party’s (PSOE) regional branches have diverged over time from their national party organization in regions with linguistic and cultural specificities, while the Popular’s Party (PP) adopts contradictory positions depending on the region on matters such as the promotion of regional languages (Gómez et al. 2014). In a context of rising tensions between territories and the national level in contemporary parliamentary democracies, I argue that opening the black box of political parties is critical in understanding their stability and cohesion (or lack thereof) today. While the primary objective of the party, both at the national and sub-national levels, is arguably to seek votes, without which they cannot attain further goals of policy and office (Müller and Strøm 1999), they have different electorates to attend and therefore more or less diverging strategies to maximize votes. This means that an MP voting against the official party line may not be dissenting from the party as a whole, but may be signalling their agreement to the party at a local or regional level.

In the remainder of this article, I show how the literature devoted to MPs’ links to their party can be used to develop a framework to explain ideological diversity within political parties under consideration of their territorial sensibilities. I will draw on the concept of intra-party ideological diversity (IPD), which I define as a collection of individual strategic behaviours through which each MP in the same party voices a position on a specific ideological continuum with regards to their party at a given level of organization. The level of ideological diversity within a party at a given moment thus results from the aggregation of behaviours, at the individual level, of party elites (on a similar argument, see Karol 2009). This individual behaviour results in voicing, in hirschmanian terms (Hirschman 1970; Close and Gherghina 2019) an ideological position. This definition stems from three main assumptions:

-

1.

Among party elites, I focus on legislators as the link between the territorial levels of their party: MPs indeed simultaneously represent their party at the national, regional and local levels.

-

2.

While the literature generally assumes that MPs have certain preferences and a certain level of attachment to their party that will explain most of their behaviour, voicing an ideological position is a positive decision legislators make with regards to their party at different levels of organization. These ideological positions are a behaviour rather than an attitude.

-

3.

In line with rational choice theory, I assume that this is a strategic behaviour to maximize their chances of re-election (Mayhew 1974), rather than the expression of intrinsic preferences and beliefs.

The next section reviews the different theories explaining the variation of ideological diversity within political parties in the field of party politics and legislative studies. In the second section, I propose to model the relations between legislators, their party and their constituents as a competitive delegation process building on the principal-agent theory and on the literature on the distribution of power within political parties.

Explaining intra-party diversity from the behaviour of MPs

In the literature, ideological diversity is most often studied through the notion of party unity, defined as voting unity in parliament. The existing models can be sorted according to three main theoretical approaches: institutional, sociological–behavioural, and electoral (Hazan 2003). Under an institutionalist framework, legislators are viewed as rational actors seeking to maximize their utility. Legislators’ goals are often summarized as policy, office and votes (Müller and Strøm 1999). The way they weight these three goals and their strategies to attain them may differ considerably. In cases of divergences, party unity is obtained primarily through discipline, defined as a set of rewards and sanctions creating incentives for MPs to toe the party line. While this approach is useful to explain occasional dissent in legislative voting behaviour on a given topic, it does not explain ideological divergences within a given party that do not translate into a voting behaviour in Parliament. Moreover, the institutional approach focuses on the incentives offered to MPs related to their goals of office and policy. In turn, incentives regarding their goal of re-election—which is arguably the primary goal of legislators—are more likely to hinge on party organization and electoral rules. I therefore focus in this section on the sociological–behavioural and electoral approaches. The sociological and behavioural approach stresses the role of informal rules and norms, acquired by MPs during a long-term process of socialization, in creating party solidarity. Finally, in the electoral approach, intra- and inter-party elections determine the value of the party’s brand for candidates and sitting legislators and ultimately, the ability for the party to create both cohesion and discipline.

The sociological–behavioural approach: party- and systemic-level determinants of party unity

Proponents of the sociological and behavioural approach have focused on determinants of party unity at the systemic and party levels shaping the behaviour of MPs in Parliament. The party acts as a socializing agent for legislative candidates who develop overtime strong ties to their party, leading to party unity. Party loyalty is internalized by legislators as the most important rule of the game before they enter parliament (Crowe 1983; Searing 1994). This approach highlights the impact of party culture and ideology on party unity. Communist, socialist and, to a lesser extent, conservative parties favour collective action and group solidarity while liberal, green and radical parties put more emphasis on individual free will. As a result, legislators from the former types of parties tend to be more cohesive than legislators from the latter (Duverger 1951; Costa and Kerrouche 2007; Gauja 2012). In a similar argument, old and stable parties and party systems are likely to yield more party unity as parties have acquired a durable reputation and loyalty from their members (Owens 2003).

Aside from culture and ideology, the way parties are organized matter to explain party unity. According to the organizational pressure theory (Ozbudun 1970), strong party organizations tend to produce high cohesion among MPs. The strength of a party organization is often defined as its institutionalization that is to say the extent to which a party is “reified in the public mind so that the “party” exists as a social organization apart from its momentary leaders, and this organization demonstrates recurring patterns of behavio[u]r valued by those who identified with it” (Janda 1980, p. 19).

Constitutional elements and characteristics of the party system can also increase the influence exerted by parties on legislators (Hazan 2003). This argument derives from both the sociological-behavioural and the institutionalist approaches as it borrows elements related to the socialization of MPs and the pursuit of rational interests. In parliamentary systems, legislative party unity is necessary for MPs to achieve their goals (Wahlke et al. 1962; Owens 2003). By contrast, presidential systems encourage individual ambitions over collective actions in order to gain important executive functions, which are independent from legislative careers (Harmel and Janda 1982; Strøm 2012). The polarization of the party system also influences the level of party unity: as the ideological distance between parties decreases, legislators may become more tempted to switch parties (Kornberg 1967). Moreover, two-party systems tend to produce greater cohesion than multi-party systems, as dissent in one party would automatically benefit the other (Ozbudun 1970).

These different conditions are not independent from each other. In particular, institutionalization is fostered by electoral success (Janda 1980) and the stabilization of its financial resources (Katz and Mair 1995), giving the party more leverage over MPs. At the same time, stable and strong parties that are certain to win elections tend to be less cohesive, as lack of competitiveness leads to the development of stronger factions (Sartori 1976). The organizational pressure theory must therefore be thought in relation to electoral considerations.

The electoral approach: individual determinants of party unity

The electoral approach, I argue, is the most important one to understand the extent of party unity. Electoral competition, both within and between parties, determines the amount of pressure the extra-parliamentary organization exerts on MPs. MPs are assumed to be rational actors primarily seeking to be re-elected: they follow the party’s line as long as it favours them electorally (Mayhew 1974). Party affiliation is usually beneficial to legislators, as it provides them with a brand and a manifesto, on the basis on which voters can re-elect them without having to know them personally. However, this brand is not always sufficient to ensure electoral success and can sometimes even hinder the candidate’s re-election chances, when the party is in difficulty at the national level or when it defends policies that are unpopular in the legislator’s district (Garraud 1994). When this is the case, MPs are more likely to dissent. The value of the party’s brand varies depending on three factors: the electoral system, the party’s competitive position and the characteristics of the candidate selection process.

Regarding electoral rules, the most important factor is whether the electoral system puts the emphasis on parties or candidates. In closed list systems, where the party controls the names and ranks of candidates in electoral lists, and therefore, the electoral fate of MPs, parties tend to be more united (Strøm 2012). Open list systems on the other hand create incentives for legislators to cater to their voters to the detriment of their national party, yielding more dissent (Carey and Shugart 1995; André et al. 2014). District magnitude, defined as the number of seats in a given district, differently affects party unity depending on the openness of lists. In single-member districts (SMD), voters can more easily reward or sanction their legislator for their actions (Cain et al. 1987; Heitshusen et al. 2005). In closed list systems, high magnitude discourages dissent as it is harder for voters to single out the legislator responsible for a given action. On the contrary, in open list systems, competitiveness increases with magnitude, encouraging MPs to dissent from the national party in order to be rewarded by the constituents (Katz 1986; Carey and Shugart 1995).

Secondly, the value of the party’s brand is strongly influenced by the party’s competitive position. When the party’s electoral prospects are not sufficient to guarantee their re-election, legislators may develop strategies that are independent from their party. Cain et al. (1987) show that MPs can cultivate a “personal vote” in order to ensure their re-election: they try to convince voters outside of their party’s electorate by mobilizing personal qualities and resources. This is especially the case in competitive SMD, where legislators can more easily develop a personal tie to their constituents (Cain et al. 1987; Heitshusen et al. 2005). Finally, the candidate selection process affects the relationship between legislators and their party. When the selection is controlled by a few party leaders, only the most loyal MPs will be selected, encouraging party unity. In very inclusive selection process—such as party primaries—legislators will depend less on their party and more on their voters, leading to lower levels of party unity (Hazan and Gideon Rahat 2010). Finally, candidacy determines the competitiveness of the re-selection process, especially when incumbent legislators are automatically re-selected by their party, which is the case of France (see Frame 1). Party unity is similarly more difficult to achieve when the selection is controlled locally rather than nationally, as MPs are likely to stay loyal to the level responsible for their re-selection in case of conflict (Bowler et al. 1996; Whiteley and Seyd 1999).

As evidenced by the electoral approach, MPs face pressure from rival sources, mainly their party and their voters. This rivalry is crucial in explaining party unity as legislators may defect from their party in order to cater to their voters. First developed in economics, the principal-agent theory states that every delegation is a process by which a principal delegates their power to an agent to act in their stead (Lupia and McCubbins 2000). This theory revolves around the idea that any delegation contains the risk that the principal cannot constantly control the actions of their agent. The latter may act according to their own interests, leading to agency losses in the delegation. Political representation can be described as a delegation in which constituents—the principals—select an MP as their agent to act on their behalf (Mitchell 2000). This relationship potentially suffers from agency losses, as the constituents cannot constantly ensure that their legislator is acting according to their best interests. These problems can happen either because the principal did not select the appropriate agent or because the principal cannot constantly keep the agent’s actions in check, leading to problems of adverse selection and moral hazard, respectively (Strøm 2000). Aside from voters, MPs are also agents of their party, which selects them as candidates to compete under their label. The party and the constituents are “competing principals”: they may have different interests but have the same agent, who is compelled to choose between them (Carey 2007). For Carey, having multiple principals negatively affects party unity when other principals than the party leaders control resources and have competing demands, pressuring MPs.

To contain agency losses and constrain legislators, voters and parties can resort to four strategies: before the delegation contract is signed (ex ante mechanisms), and after (ex post mechanisms) (Kiewiet and McCubbins 1991). Ex ante mechanisms help the principal ensure of the loyalty of their agent and of their shared interests in pursuing the actions delegated. Through contract design, the principal can ensure that they share similar interests with the agent before entering the delegation. Before the delegation, the principal can ensure of the loyalty and professionalism of their agent by the screening and selection of potential agents. The extent to which parties and voters can resort to these mechanisms to contain agency losses vary depending on the value of the party’s brand, as discussed earlier in this section.

Ex post mechanisms help the principal ensure that the agent acts according to the principal’s best interests during the delegation, through monitoring and reporting, and institutional checks. The principal can either directly monitor the agent (police patrols) or rely on third-party monitoring (fire alarms) (Mitchell 2000). Direct monitoring on the one hand is expensive in terms of time and resources. Constituents are unlikely to be able to directly monitor their legislator, although monitoring should be facilitated in SMD and small constituencies, where the legislator is more likely to be personally known by the constituents. On the other hand, indirect monitoring can be unreliable, as third-parties monitoring—from media, associations or other politicians—can hide or disguise facts to the principals to serve their own interests (Lupia and McCubbins 1994). Today, constituents have increasing means to indirectly monitor their legislator, through parliamentary monitoring associations, such as Nos Députés in France (Edwards et al. 2015), but also through self-reporting by legislators themselves on social media, which is often relayed by the traditional media (Chibois 2014; Kelm et al. 2019). Through institutional checks, the principal relies on the veto powers of third-parties to prevent their agent’s most questionable actions. For both the constituents and the party principals, these third-parties are typically parliamentary authorities investigating improper practices such as corruption (Mitchell 2000). These institutional checks however are restricted to illegal practices only. In addition, in European parliamentary democracies, the mandate of legislators cannot be revoked when they are expelled from their party or when voters are dissatisfied with their actions, leaving the threats of not re-selecting or not re-electing the incumbent legislator the most important bargaining power of the party principals and the constituents, both before and during the delegation (Strøm 2012).

A competitive delegation process between MPs, their party and their constituents

Most of the models I presented primarily define party unity as MPs being close to their party. More often than not, parties are treated as unitary actors without any further distinction. These models often implicitly refer to incentives stemming from the territorial layers of parties that may affect the behaviour of MPs. For instance, the allocation of resources and offices can be controlled by the regional party, or legislators may have been socialized in a local section with norms that are distinct from the rest of the party. Similarly, voters can have specific demands depending on the economic, social or political characteristics of the constituency. Yet, proximity to other levels of the party is rarely explicitly discussed while territorial conflicts are central in explaining ideology within and between parties. According to cleavage theory, parties express and structure conflicts within societies, and are created from four main cleavages, both of which related to territorial disparities: the centre-periphery and the urban–rural cleavages (Lipset and Rokkan 1967). Although weakened by the nationalization of political competition and electoral behaviours during the twentieth century (Caramani 2004), territorial conflicts have resurged since the 1970s in Europe following decentralization policies and the rise of regionalist parties and regionalist claims, especially in Belgium, the United Kingdom and Spain (de Winter and Türsan 1998). Parties have to organize and compete simultaneously at the local, regional and national elections, and have to attend to voters in territories with high economic, social, linguistic or cultural disparities. As a result, territorial disparities can explain a great deal of ideological variations within parties. Their effect on party unity is probably mediated by the party’s generic type, regarding whether it was created under the impulsion of the centre (territorially penetrated) or by local elites (territorially diffuse) (Panebianco 1982), and by the State organization, as parties tend to develop strong sub-national branches in decentralized and federal countries (Filippov et al. 2004; Pogorelis et al. 2005). Moreover, the effect of territorial disparities is likely to depend on whether the electoral system creates incentives for MPs to cater to their constituents instead of their parties. Taking into account the territorial variations of ideological positions within parties can help us reconsider the expression of dissenting positions among legislators from the same party. Dissent from the national party, as traditionally defined in the literature, is not necessarily dissent from the party as a whole, but can be a way for MPs to signal their proximity to another level of the party, a situation I define as diversity.

Intra-party ideological diversity: a definition

The concept of intra-party ideological diversity (IPD) allows us to take this idea into account. IPD can be defined as a collection of individual behaviours through which each MP in the same party voices a position on a specific ideological continuum with regards to their party at a given level of organization. Voice, in hirschmanian terms (Hirschman 1970; Close and Gherghina 2019), is not necessarily a form of dissent, as the position may be more or less close to the level concerned. It can also be a way for the individual legislator to express their proximity to another level of the party. IPD can be defined at different levels: for instance, IPD at the national level is the aggregation of individual distances between the position of each MP and that of their national party. In a similar way, IPD at the regional level is the collection of distances between each legislator and their regional party. For the purpose of simplicity, I define a party composed of two sub-groups, A and B. They could, for example, stand for the national and local party organizations. Let IPDiA and IPDiB be the positions a given individual MPi voices with regards to A and B, respectively (IPDA and IPDB would be the aggregation of the individual distances IPDiA and IPDiB of every legislator in the party considered):

-

When the position voiced by the MP is close to both A and B (low IPDiA and IPDiB), it means that the legislator and both party sub-groups share a similar position, leading to an outcome of unity.

-

When the MP voices a position that is close to one group but far from the other (low IPDiA and high IPDiB or high IPDiA and low IPDiB), it means that the two sub-groups have different positions and the legislator chooses to follow one of them. In the case of national and local party organizations, the MP could be closer to their local party organization for instance. We call this situation diversity, as the MP is not dissenting from their party as a whole.

-

Finally, when the legislator voices a position that is far from both sub-groups (high IPDiA and IPDiB), it means that regardless of whether A and B share similar positions, the MP takes a different one that is not tied to their party. We call this final situation dissent.

The operationalization of IPD is beyond the scope of this article, but we have discussed elsewhere how ideological positions, of political elites and party organizations alike, can be estimated and compared with one another from social media data (Ecormier-Nocca and Louis-Sidois 2019; Ecormier-Nocca and Sauger 2020).

Party territorial layers as competing principals

Proponents of the principal-agent framework tend to think of the constituency and the party as two distinct factors of influence on the legislator. And yet, the party can be broken down into further entities. Parties are simultaneously present at different levels of territorial organizations. They represent their voters and activists locally and nationwide but also, with the development of decentralization policies, at the regional level. As national representatives elected locally, MPs can be seen as agents of their party at these different levels of organizations. While the different principals within the party all share the same goal, which is the overall electoral success of the party, their strategies to achieve it may contradict one another. Therefore, I propose to adopt the principal-agent model discussed before so as to model the relations between legislators, their party and their constituency as a delegation process, where MPs are the agents of four competing principals: the party at the national (1), regional (2) and local (3) levels, and the constituents (4). These principals may exert contradictory pressures on legislators:

-

1.

The national party. The attitude of the national party organization with regards to MPs results from a trade-off between the need for a stable and efficient organization and the need to account for diversity across territories and across voters, both of them necessary to achieve electoral success. On the one hand, the national party organization should seek to maintain an internal coherence among MPs: disunited parties cannot properly function in parliament and are deemed unfit to govern by voters (Kam 2009). On the other hand, organizing diversity behind closed doors, through factions or tendencies for instance, can be a way to contain visible manifestations of dissent, such as individual party-switching and collective splits (Boucek 2003). Diversity can also be a strategy to maximize integration and thus appeal to a broader base of voters, a strategy prevalent among “catch-all” parties (Kirchheimer 1966). Similarly, parties can choose to blur their position on a given issue that is divisive among their ranks (Rovny 2012). Finally, allowing diversity among sub-national branches can solve territorial conflicts and maximize the electoral success of the overall party (Filippov et al. 2004). All these situations may lead to MPs moving away from their national party without it to be a situation of dissent, but rather a situation of negotiated diversity.

-

2.

The local party. At the sub-national levels, the regional and local party branches must attend to a specific electorate, which might be socially, ethnically, politically or linguistically different from other constituencies and regions. As a principal of MPs, the local party branch in particular should exert a pressure on them to move away from their national party and closer to their party at the local level in order to cater for these territorial characteristics when either the constituency as a whole, or the local party voters in particular, are significantly different from the rest of the population. This creates a first source of tensions within the party, between the national party and the local party branch: MPs are national representatives, but they represent to some extent their constituency in parliament (Masclet 1982; Abélès 1989), even more so when the candidate selection process takes place at the local level.

-

3.

The regional party. With the development of decentralization policies in European democracies since the 1980s, parties have increased incentives to present a unified front at the regional level to compete for regional elections and participate in regional government and parliaments. In this sense, legislators answer to some extent to their regional party branch, even more so when they are selected at this level. When either the regional party voters or the regional voters as a whole are sufficiently different from the national voters, the regional party branch should simultaneously exert two types of pressure of MPs. First, they should expect MPs to move away from the national party and closer to the regional party, thus a pressure for differentiation with regards to the national party level, creating a second source of tensions within the party, between the national party and the regional branch. At the same time, they should exert on all MPs from the same region a pressure for orthodoxy with regards to the regional party branch. This should create a third potential sources of tension within the party, between the regional and the local party branches. Indeed, the local party branch may exert a pressure on MPs to move away from their party at both the national and regional levels when the constituency is significantly differentiated from other constituencies in the same region.

Asides from usual agency losses inherent to any delegation process, the different principals of MPs, their party and their voters therefore compete against one another for their common agent to act on their behalf. The principal each MP ultimately prioritizes explains the ideological position they voice. IPD therefore hinges on two main problems: agency losses and competing principals. It follows from the principal-agent theory that when confronted with competing principals, the agent should choose the principal with the most capacity to contain agency losses—as the agent will have a harder time shirking the delegation. As I developed in the previous section, the most important mechanisms are (re-)selection and (re-)election. Thus, when facing competing principals with contradictory expectations, MPs should follow the most powerful principal with regards to these two mechanisms. In particular, electoral rules (party- or candidate-centred system and magnitude) and the candidate selection (inclusiveness, level and candidacy) should have two effects. First, determining the capacity for legislators to exist independently from their party, making the constituents their main principal. Second, when the party takes precedence over the constituency, determining the extent to which each party principal can control the legislator’s goals of re-election and re-selection.

From competing to coordinating principals: the intra-party vertical bargains

Until now, I assumed that when principals share a common agent, they are always competing and never coordinating with each other. However, in the particular case of MPs, three of their principals are components of the same organization: the party at the local, regional and national levels. These three principals share ultimate goals, among which the electoral success of the overall party. One party principal may allow they agent to shirk, when doing so benefits the whole party, a situation I define as negotiated diversity rather than dissent. We therefore bring one modification to the principal-agent theory, which is the existence of bargains between competing principals, whose issue will determine the ultimate principal the agent will choose. This question is best described through the notion of stratarchy, applied to political parties by Eldersveld (1964). The notion of stratarchy implies that power in political parties is dispersed through multiple centres, rather than concentrated in one. Building on this concept, Carty (2004) proposes that parties are franchise systems, like business firms. Party levels enjoy varying levels of autonomy but are interdependent on one another: the national party organization provides a label and a national manifesto, and the sub-national branches adapt the party brand to the local environment, mobilizing voters on the ground. In this model, stratarchy is a mix of hierarchy and decentralization, and can be placed in “the middle of a continuum of power-concentration and power-dispersion” (Bolleyer 2012, p. 317). With Wolinetz (2015), I propose to view the national regional and local party organizations as three poles with a certain amount of resources, linked together by vertical bargains allocating power among them. We define stratarchy as a scale: when the power is mainly concentrated at the national level, the level of stratarchy is low and the party’s organization resembles that of a hierarchy. The more dispersed the power between the party levels, the higher the level of stratarchy. The party’s organization is more decentralized, coming closer to that of a federation.

We argue that the higher the level of stratarchy in a given party, the higher IPD will tend to be. The notion of intra-party vertical bargains entails that the different party principals are aware of sharing a common agent—the legislator. When their interests diverge, they engage in bargains to determine which of them their agent should prioritize over the others. For instance, local and national party organizations could have differing views on a given issue and therefore have contradictory expectations on how their agent should act. If the overall party structure is decentralized, with well-developed local party organizations, and that this peculiar local party organization performs better electorally than the rest of the party at the national level, the national party organization is more likely to allow the legislator to move away from them and closer to their local party principal for two reasons. To begin with, when sub-national branches concentrate sufficient material and human resources, they can address territory-specific concerns. The adaptation of the national party’s line to tailor to the interests and preferences of the constituents’ enhances the creation of an autonomous electoral market and fosters the rise of local political figures (Botella and Teruel 2010). In turn, both the constituents and the local politicians will have more influence over potential legislative candidates seeking to be nominated or elected in the district. Secondly, facing the development of a specific and successful local political sphere, the national party organization may allow legislators to adopt diverging positions in order to secure their seat in the district and maximize the success of the overall party. In this situation, this negotiated diversity is beneficial for all actors involved: for the local party, obviously, which minimizes its agency losses. For the legislator, who is more likely to ensure their re-election goals by choosing the principal with the highest electoral strength. Maximizing MP’s re-election chances is also in the best interests of the national party, as long as their agent’s shirking stays within a certain limit and does not damage the overall party. To put it simply, intra-party bargains are power struggles, where the party subgroup with the highest organizational and electoral strengths wins over the other. They can therefore be confrontational in nature, when the strongest party level asserts itself, or fall within the mutual interests of the actors involved, when diversity is beneficial for the overall party. The argument is not at odds with the principal-agent theory: the party principal with the most organizational and electoral strength has the most capacity to contain agency losses, as they have generally more power over the selection of candidates within the party, but are also able to promise the legislator a higher cut of the gains—in terms of votes, policy or office—than the other party principals.

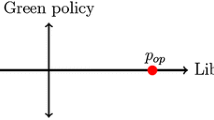

Explaining IPD: a model

Therefore, I develop the following model, which is summed up in Fig. 1. When their competing principals have contradictory expectations on how they should behave, MPs will choose (i.e. move closer to) the principal the most likely to maximize their chances of (re-)election. This choice hinges on two main factors: a power struggle between the party principals, and a power struggle between the legislator and their party as a whole. The latter explains whether legislators go away from their party at all levels in order to cater to their constituents (dissent) or get close to any level of their party. The former explains whether MPs move closer to their national party (unity) or towards their local or regional branch (diversity). Regarding the power struggle between party principals, the relative capacity of each party level to contain agency losses determines their capacity to constrain legislators to act accordingly to their own interests. This capacity largely results from the intra-party vertical bargains, which allocate power between the different party levels, and set the party level MPs are most likely to follow in case of conflict. Three main sets of factors may affect the outcomes of intra-party vertical bargains:

-

First, the regional autonomy establishes the administrative and cultural relevance of the sub-national party branches with regards to the national party: sub-national party branches are likely to hold more power in States with a decentralized structure and in territories that are distinguishable from one another beyond administrative boundaries regarding the concentration of ethnic, linguistic, religious groups or important economic disparities (Filippov et al. 2004; Pogorelis et al. 2005).

-

Second, the relative electoral strength of each party principal determines which party level is most able to ensure the legislator’s electoral success and therefore maximize the electoral gains of the overall party.

-

Finally, characteristics of party organization set both the capacity for the national party to impose their line and for the sub-national branches to resist it. More specifically, MPs should move away from their national party and towards their local or regional branches in parties with a high level of decentralization—where conflicts are more likely to occur—and where candidates are selected at those levels.

The ability of MPs to resist their party as a whole can be defined as their ability to exist in the minds of their voters and succeed independently from their party’s label or, in other words, the ability to cultivate a “personal vote” (Cain et al. 1987; Heitshusen et al. 2005). This autonomy is created by a mixture of institutional and personal characteristics that I presented earlier: the electoral rules, the candidate selection process and the legislator’s own electoral strength and resources.

Conclusion

In this article, I sought to shed new light on the diversity within political parties defined as the variance in the ideological positions of their individual legislators. I introduced the concept of intra-party ideological diversity (IPD), to account for the fact that when legislators are dissenting towards their national party, they may not be dissenting from their party as a whole, a situation I define as diversity, as a third outcome between unity and dissent. While the literature explaining intra-party diversity from the behaviour of MPs tends to approach parties as unitary actors, I show that it makes sense to consider proximity to other levels than the national party organization. MPs indeed rely on four main actors to achieve their goals: their constituents and their party at the national, regional and local level.

I then showed how principal-agent theory can be adapted so as to model the relations between MPs and these different actors as a competitive delegation process. The main expectation derived from this model is that when confronted with contradictory expectations from their principals, legislators move closer to the one from which they expect most electoral returns. This choice hinges on two main factors that are likely to shed light, respectively, on variations at the party and at the individual level. First, the intra-party vertical bargains allocating power between the territorial layers of parties: in case of conflict, the national party organization may allow legislators to move closer to sub-national party branches when doing so increase the electoral success of the overall party. These bargains lead to a situation of diversity rather than dissent, as legislators are still choosing one of their party principals. Second, MPs’ own resources and relationship with their constituents define their level of autonomy with regards to their party, and thus, their capacity to dissent from their party at all levels.

Understanding why parties are more or less united is a crucial question, in political science, but for democracy in general, especially in the light of rising territorial conflicts in contemporary Europe. This article represents an effort in this direction, by proposing to open the black box of territorial party organization. An obvious and necessary continuation of this work would be to take into account other delegation processes between the different party territorial layers and party elites such as members of regional parliaments and mayors but also members of the European Parliament, and how they shape intra-party ideological diversity across territories.

References

Abélès, Marc. 1989. Jours tranquilles en 89: Ethnologie politique d’un département français. Paris: Olivier Jacob.

Achin, Catherine, Anja Durovic, Éléonore Lépinard, Sandrine Lévêque, and Amy G. Mazur. 2019. Parity Sanctions and Campaign Financing. in France: Increased Numbers, Little Concrete Gender Transformation. In Gendered Electoral Financing Money, Power and Representation in Comparative Perspective, ed. Ragnhild L. Muriass, Vibeke Wang, and Rainbow Murray, 27–54. Basingstoke: Routledge.

André, Audrey, André Freire, and Zsófia Papp. 2014. Electoral Rules and Legislators’ Personal Vote-seeking. In Representing the People, ed. Kris Deschouwer and Sam Depauw, 87–109. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Boelaert, Julien, Sébastien Michon, and Étienne Ollion. 2018. Le temps des élites. Ouverture politique et fermeture sociale à l’Assemblée nationale en 2017. Revue française de science politique 68 (5): 777–802. https://doi.org/10.3917/rfsp.685.0777.

Bolleyer, Nicole. 2012. New Party Organization in Western Europe: Of Party Hierarchies, Stratarchies and Federations. Party Politics 18 (3): 315–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068810382939.

Botella, Joan, and Juan Rodríguez Teruel. 2010. Hommes d’État ou tribuns territoriaux? Le recrutement des présidents des Communautés autonomes en Espagne. Pôle Sud 33 (2): 7–25.

Boucek, Françoise. 2003. The Structure and Dynamics of Intra-Party Politics in Europe. In Pan-European Perspectives on Party Politics, ed. Paul Lewis and Paul Webb, 55–95. Leiden: Brill.

Bowler, Shaun, David M. Farrell, and Ian McAllister. 1996. Constituency Campaigning in Parliamentary Systems with Preferential Voting: Is There a Paradox? Electoral Studies 15 (4): 461–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0261-3794(96)00036-4.

Cain, Bruce, John Ferejohn, and Morris Fiorina. 1987. The Personal Vote: Constituency Service and Electoral Independence. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Caramani, Daniele. 2004. The Nationalization of Politics. The Formation of National Electorates and Party Systems in Western Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Carey, John M. 2007. Competing Principals, Political Institutions, and Party Unity in Legislative Voting. American Journal of Political Science 51 (1): 92–107. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00239.x.

Carey, John M., and Matthew Soberg Shugart. 1995. Incentives to Cultivate a Personal Vote: A Rank Ordering of Electoral Formulas. Electoral Studies 14 (4): 417–439. https://doi.org/10.1016/0261-3794(94)00035-2.

Carty, R. Kenneth. 2004. Parties as Franchise Systems: The Stratarchical Organizational Imperative. Party Politics 10 (1): 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068804039118.

Chibois, Jonathan. 2014. Twitter et les relations de séduction entre députés et journalistes: La salle des Quatre Colonnes à l’ère des sociabilités numériques. Réseaux 188 (6): 201–228. https://doi.org/10.3917/res.188.0201.

Close, Caroline, and Sergiu Gherghina. 2019. Rethinking Intra-party Cohesion: Towards a Conceptual and Analytical Framework. Party Politics 25 (5): 652–663. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068819836044.

Costa, Olivier, and Éric Kerrouche. 2007. Qui sont les députés français? Enquête sur des élites inconnues. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po.

Crowe, Edward. 1983. Consensus and Structure in Legislative Norms: Party Discipline in the House of Commons. The Journal of Politics 45 (4): 907–931. https://doi.org/10.2307/2130418.

de Winter, Lieven, and Huri Türsan (eds.). 1998. Regionalist Parties in Western Europe. London: Routledge.

Duverger, Maurice. 1951. Les Partis Politiques. Paris: Armand Colin.

Ecormier-Nocca, Florence, and Charles Louis-Sidois. 2019. Fronde 2.0. Les députés français sur Twitter. Revue française de science politique 69 (3): 481–500. https://doi.org/10.3917/rfsp.693.0481.

Ecormier-Nocca, Florence, and Nicolas Sauger. 2020. Advances in Measuring Elite-Mass Linkages: The Internet as a source. In The Handbook on Political Partisanship, ed. Henrik Oscarsson and Sören Holmberg, 141–153. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

Edwards, Arthur, Dennis de Kool, and Charlotte van Ooijen. 2015. The Information Ecology of Parliamentary Monitoring Websites: Pathways Towards Strengthening Democracy. Information Polity 20 (4): 253–268. https://doi.org/10.3233/IP-150372.

Eldersveld, Samuel. 1964. Political Parties: A Behavioral Analysis. Chicago: McNally.

Esther Herrmann, Lise. 2017. Democratic Partisanship: From Theoretical Ideal to Empirical Standard. American Political Science Review 111 (4): 738–754.

Filippov, Mikhail, Peter Ordeshook, and Olga Shvetsova. 2004. Designing Federalism. A Theory of Self-sustainable Federal Institutions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Garraud, Philippe. 1994. Les contraintes partisanes dans le métier d’élu local. Sur quelques interactions observées lors des élections municipales de 1989. Politix 7 (28): 113–126. https://doi.org/10.3406/polix.1994.1886.

Gauja, Anika. 2012. Party Dimensions of Representation in Westminster Parliaments: Australia, New Zealand and the United Kingdom. In Parliamentary Roles in Modern Legislatures, ed. Magnus Blomgren and Olivier Rozenberg, 121–144. London: Routledge.

Gómez, Braulio, Laura Cabez, and Sonia Alonso. 2014. Los partidos estatales ante el laberinto autonómico. In Elecciones autonómicas 2009-2012, ed. Francesc Pallarés i Porta, 75–113. Madrid: Centro de Investigaciones Sociológicas.

Harmel, Robert, and Kenneth Janda. 1982. Parties and Their Environments: Limits to Reform?. New York: Longman.

Hazan, Reuven Y. 2003. Introduction. Does Cohesion Equal Discipline? Towards a Conceptual Delineation. The Journal of Legislative Studies 9 (4): 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/1357233042000306227.

Hazan, Reuven Y., and Gideon Gideon Rahat. 2010. Democracy within Parties: Candidate Selection Methods and their Political Consequences. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heitshusen, Valerie, Garry Young, and David M. Wood. 2005. Electoral Context and MP Constituency Focus in Australia, Canada, Ireland, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom. American Journal of Political Science 49 (1): 32–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0092-5853.2005.00108.x.

Hirschman, Albert O. 1970. Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Janda, Kenneth. 1980. Political Parties: A Cross-national Survey. New York: Free Press.

Kam, Christopher. 2009. Party Discipline and Parliamentary Government. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Karol, David. 2009. Party Position Change in American Politics: Coalition Management. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Katz, Richard. 1986. Intrapreference Party Voting. In Electoral Laws and Their Political Consequences, ed. Bernard Grofman and Arend Lijphart, 85–103. New York: Agathon Press.

Katz, Richard, and Peter Mair. 1995. Changing Models of Party Organization and Party Democracy: The Emergence of the Cartel Party. Party Politics 1 (1): 5–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1354068895001001001.

Kelm, Ole, Marco Dohle, and Uli Bernhard. 2019. Politicians’ Self-Reported Social Media Activities and Perceptions: Results From Four Surveys Among German Parliamentarians. Social Media + Society. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305119837679.

Kiewiet, D.Roderick, and Mathew D. McCubbins. 1991. The Logic of Delegation: Congressional Parties and the Appropriations Process. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kirchheimer, Otto. 1966. The Transformation of Western European Party Systems. In Political Parties and Political Development, ed. Joseph La Palombara and Myron Weiner, 177–200. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Kornberg, Allan. 1967. Canadian Legislative Behavior: A Study of the 25th Parliament. Toronto: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

Laurent, Annie, and Christian-Marie Wallon-Leducq. 1998. Les candidats aux élections législatives de 1997 sélection et dissidence. In Le vote surprise. Les élections législatives du 25 mai et 1er juin 1997, ed. Colette Ysmal and Pascal Perrineau, 138–199. Paris: Presses de Sciences Po.

Lipset, Seymour, and Stein Rokkan (eds.). 1967. Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. New York: Free Press.

Lupia, Arthur, and Mathew D. McCubbins. 1994. Learning From Oversight: Fire Alarms and Police Patrols Reconstructed. Journal of Law Economics and Organization 10 (1): 96–125. https://doi.org/10.1093/jleo/10.1.96.

Lupia, Arthur, and Mathew D. McCubbins. 2000. Representation or Abdication? How Citizens Use Institutions to Help Delegation Succeed. European Journal of Political Research 37 (3): 291–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00514.

Masclet, Jean Claude. 1982. Un député, pour quoi faire?. Paris: Presses universitaires de France.

Mayhew, David. 1974. Congress. The Electoral Connection. New Have: Yale University Press.

Mitchell, Paul. 2000. Voters and Their Representatives: Electoral Institutions and Delegation in Parliamentary Democracies. European Journal of Political Research 37 (3): 335–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00516.

Müller, Wolfgang C., and Kaare Strøm (eds.). 1999. Policy, Office, or Votes? How Political Parties in Western Europe Make Hard Decisions. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Owens, John E. 2003. Part 1: Cohesion. Explaining Party Cohesion and Discipline in Democratic Legislatures. The Journal of Legislative Studies 9 (4): 12–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/1357233042000306236.

Ozbudun, Ergun. 1970. Party Cohesion in Western Democracies: A Causal Analysis. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

Panebianco, Angelo. 1982. Modelli di partito: organizzazione e potere nei partiti politici. Bologna: Il Mulino.

Pogorelis, Robertas, Bart Maddens, Wilfried Swenden, and Élodie Fabre. 2005. Issue Salience in Regional and National Party Manifestos in the UK. West European Politics 28 (5): 992–1014. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380500310667.

Rovny, Jan. 2012. Who Emphasizes and Who Blurs? Party Strategies in Multidimensional Competition. European Union Politics 13 (2): 269–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116511435822.

Sartori, Giovanni. 1976. Parties and Party Systems: A Framework for Analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Sauger, Nicolas. 2009. Party Discipline and Coalition Management in the French Parliament. West European Politics 32 (2): 310–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/01402380802670602.

Searing, Donald D. 1994. Westminster’s World: Understanding Political Roles. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Squarcioni, Laure. 2017. Devenir candidat en France: règles et pratiques de sélection au PS et à l’UMP pour les élections législatives. Politique et sociétés 36 (2): 13–38. https://doi.org/10.7202/1040411ar.

Strøm, Kaare. 2000. Delegation and Accountability in Parliamentary Democracies. European Journal of Political Research 37 (3): 261–289. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.00513.

Strøm, Kaare. 2012. Roles as Strategies. Towards a Logic of Legislative Behavior. In Parliamentary Roles in Modern Legislatures, ed. Magnus Blomgren and Olivier Rozenberg, 85–100. London: Routledge.

Wahlke, John, Heinz Eulau, and William Buchanan. 1962. The Legislative System: Explorations in Legislative Behavior. New York: Wiley.

Whiteley, Paul, and Patrick Seyd. 1999. Discipline in the British Conservative Party: The Attitudes of Party Activists toward the Role of their Members of Parliament. In Party Discipline and Parliamentary Government, ed. Shaun Bowler, David Farrell, and Richard Katz, 53–71. Columbus: Ohio State University Press.

Wolinetz, Steven B. 2015. Franchising the Franchise Party. How Far Can a New Concept Travel? In Parties and Party Systems: Structure and Context, ed. Richard Johnston and Campbell Sharman, 72–91. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Isabelle Guinaudeau for her helpful comments and suggestions. This review draws on the author’s dissertation on ideological diversity within political parties.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ecormier-Nocca, F. Mapping ideological diversity from inside parties: A principal-agent approach. Fr Polit 18, 433–449 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41253-020-00132-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41253-020-00132-8