Abstract

Self-employment among immigrants is a key source for income and social assimilation with natives. Rate of self-employment is significantly higher for immigrants than for native-born individuals, and the causal reasons behind this differential are still not well understood. We hypothesize that a key factor is that domestic employers often cannot accurately assess the quality of higher education received by the immigrants in their home countries. This lowers immigrants’ return to human capital in the traditional job market relative to natives. Our hypothesis predicts that this factor should be reflected in higher relative rates of self-employment for immigrants that rises with the level of education. We test and confirm this hypothesis using IPUMS micro-data from the USA.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For evidence regarding the impact of language proficiency and skill see Borjas (1994), Dustman and Fabbri (2003), and Card (2001, 2005) for the USA, and Barrett et al. (2012), for the European Union.Coate and Tennyson (1992) provide an explanation of self-employment in the presence of labor market discrimination. Yuengert (1995) finds that one determinant of immigrant self-employment was the self-employment rates at the immigrant’s home country. Constant and Zimmermann (2003) find occupational choice of immigrants is influenced by the choices of their parents, especially mothers.

Whether these differences disappear (converge with native-born wages) after long periods in the USA is still debated in the empirical literature. Lofstrom (2002) finds that even after long periods in the United States these wage differentials persist, while Borjas (1994) finds that immigrant earnings converge to natives in about 15 years and may eventually get reversed. For wage gaps in other countries see the Global Wage Report 2014/15 (ILO 2016) and Barrett et al. (2012).

The manifestation of asymmetric information as low skill workers flooding the wage employment is analogous to Akerlof’s (1970) classic discussion of ‘lemons’ in the market for automobiles.

Statistical discrimination occurs when distinctions between groups are made on the basis of real or imagined statistical distinctions (e.g., immigrant workers being offered lower wages because they are perceived as less productive, on average, than native workers).

The actual output or productivity of low-skilled workers is also easier to monitor and quicker to ascertain relative to the corresponding variables for high-skilled, high human capital, workers.

In addition to racial discrimination and other social and demographic effects that differ, there are other factors that may specifically, and differentially, impact self-employment and the returns to higher education including affirmative action programs (Yuengert 1995; Fairlie and Meyer 1996; Fairlie et al. 2012). Due to these differences across races, we focus on white individuals which is the largest racial group in the sample. Seeing how these results hold up for other racial groups and for other countries would be an interesting future avenue for research. It is worthwhile to note that of the immigrants living in the USA, those classified as white are the largest single group, accounting for almost 46% of the total.

Individuals are classified based on their highest degree earned. So for example a person who started but did not finish college would be coded with a value of 1 for earning a high school degree only. The literature has found important nonlinear effects of degree completion (e.g., large discontinuities based on years of education surrounding the degree completion events), and since our hypothesis is about the value of these credentials, coding degree completion is preferable to a variable simply based on the years of education.

In the probit model, the inverse standard normal distribution of the probability is modeled as a linear combination of the predictors. Our results are robust to using linear probability (LPM) or Logistic specifications.

The specifications using two subsamples also allow the coefficients on the other control variables to differ across the groups as well, although given the smaller sample sizes they are estimated with lower precision, especially for the smaller immigrant subsample. The combined specification assumes these other coefficients are similar across the groups with the exception of the education effect. The key advantage of the combined model is the direct ability to test for the statistical significance of the differential educational effect.

Again, however, because industry choice can be endogenous, while we wish to show our results are robust to including these controls, we are more confident in our estimates from specification 4 than specification 5 due to potential endogeneity issues affecting all coefficient estimates in that specification.

Using our preferred specification, college-educated immigrants have a 2.3% higher probability of self-employment, of which 0.9% is a constant effect for all immigrants unrelated to education, and the remaining 1.4% is due to the education variable interaction. Immigrants with a high school education have a 1.6% higher probability of self-employment, of which 0.9% is a constant effect for all immigrants unrelated to education, and the remaining 0.7% is due to the education variable interaction.

References

Akay, Alpasian, Amelie Constant, and Corrado Giulietti. 2014. The impact of immigration on the well-being of natives. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 103 (C): 72–92.

Akerlof, George A. 1970. The market for “lemons”: Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics 84 (3): 488–500.

Barrett, Alan, Séamus McGuinness, and Martin O’Brien. 2012. The immigrant earnings disadvantage across the earnings and skill distributions: The case of immigrants from the EU’s new member states. The British Journal of Industrial Relations 50 (3): 457–481.

Beladi, Hamid, and Saibai Kar. 2015. Skilled and unskilled immigrants and entrepreneurship in a developed country. Review of Development Economics 19 (3): 666–682.

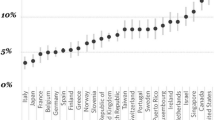

Blanchflower, David G. 2000. Self-employment in OECD countries. Labour Economics 7 (5): 471–505.

Borjas, George J. 1986. The Self-employment experience of immigrants. Journal of Human Resources 21 (4): 485–506.

Borjas, George J. 1994. The economics of immigration. Journal of Economic Literature 32: 1667–1717.

Borjas, George J. 2000. The case for choosing more skilled immigrants. American Enterprise 11 (8): 30–31.

Budig, Michelle J. 2006. Gender, self-employment, and earnings: The interlocking structures of family and professional status. Gender & Society 20 (6): 725-753

Cahill, Kevin E., Michael D. Giandrea, and Joseph F. Quinn. 2013. New evidence on self-employment transitions among older Americans with career jobs, Working Paper #463. Washington, DC: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Card, David. 2001. Immigrant inflows, native outflows, and the local labor market impacts of higher immigration. Journal of Labor Economics 19 (1): 22–64.

Card, David. 2005. Is the new immigration really so bad? The Economic Journal 115 (507): 300–323.

Chau, Nancy H., and Oded Stark. 1999. Migration under asymmetric information and human capital formation. Review of International Economics 7: 455–483.

Clark, Kenneth, and Stephen Drinkwater. 2000. Pushed out or pulled in? Self-employment among ethnic minorities in England and Wales. Labour Economics 7: 603–628.

Coate, Stephen, and Sharon Tennyson. 1992. Labor market discrimination, imperfect information and self-employment. Oxford Economic Papers 44 (2): 272–288.

Constant, Amelie F., Martin Kahanec, and Klaus F. Zimmermann. 2009. Attitudes towards immigrants, other integration barriers, and their veracity. International Journal of Manpower 30 (1/2): 5–14.

Constant, Amelie F., and Klaus F. Zimmermann. 2003. Occupational choice across generations. Applied Economics Quarterly 49: 299–317.

Destré, Guillaume, and Valentine. Henrard. 2004. The determinants of occupational choice in Colombia: An empirical analysis. Cahiers de la Maison des Sciences Economiques, Maison des Sciences Economiques, Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne.

Dustmann, Christian, and Francesca Fabbri. 2003. Language proficiency and labor market performance of immigrants in the UK. Economic Journal 113 (489): 695–717.

Dustmann, Christian, Francesca Fabbri, and Ian Preston. 2005. The impact of immigration on the British Labor market. Economic Journal 115 (507): F324–F341.

Fairlie, Robert W. 1996. Ethnic and racial entrepreneurship: A study of historical and contemporary differences. London: Garland Publishing.

Fairlie, Robert W. 2002. Drug dealing and legitimate self-employment. Journal of Labor Economics 20 (3): 538–567.

Fairlie, Robert W., Harry Krashinsky, Julie Zissimopoulos, and Krishna B. Kumar. 2012. Indian entrepreneurial success in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. Research in Labor Economics 36: 285–319.

Fairlie, Robert W., and Bruce M. Meyer. 1996. Ethnic and racial self-employment differences and possible explanations. The Journal of Human Resource 31 (4): 757–793.

International Labor Organization. 2016. Global Wage Report 2014/15. Geneva: ILO.

Katz, Eliakim, and Oded Stark. 1987. International migration under asymmetric information. Economic Journal 97 (387): 718–726.

Kerr, Gerry, and Marjorie Armstrong-Stassen. 2011. The bridge to retirement: Older workers’ engagement in post-career entrepreneurship and wage-and-salary employment. The Journal of Entrepreneurship 20 (1): 55–76.

Koellinger, Philipp, Maria Minniti, and Christian Schade. 2013. Gender differences in entrepreneurial propensity. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 75 (2): 213–234.

Leoni, Thomas, and Martin Falk. 2010. Gender and field of study as determinants of self-employment. Small Business Economics 34 (2): 167–185.

Lofstrom, Magnus 2002. Labor market assimilation and the self-employment decision of immigrant entrepreneurs. Journal ofPopulation Economics 15 (1): 83–114.

Lofstrom, Magnus. 2017. Immigrant entrepreneurship: Trends and contributions. Cato Journal 37 (3): 503–522.

Ohlsson, Henrik, Per Broomé, and Pieter Bevelander. 2010. The self-employment of immigrants and natives in Sweden. IZA Discussion Paper No. 4976, IZA Germany.

Reitz, Jeffrey G., Josh Curtis, and Jennifer Elrick. 2014. Immigrant skill utilization: Trends and policy issues. Journal of International Migration and Integration 15 (1): 1–26.

van Solinge, Hanna. 2014. Who opts for self-employment after retirement? A longitudinal study in The Netherlands. European Journal of Ageing 11 (3): 261–272.

Verheul, Ingrid, Roy Thurik, Isabel Grilo, and Peter van der Zwan. 2012. Explaining preferences and actual involvement in self-employment: Gender and the entrepreneurial personality. Journal of Economic Psychology 33 (2): 325–341.

Yuengert, Andrew. 1995. Testing hypotheses of immigrant self-employment. The Journal of Human Resources 30 (1): 194–204.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to two anonymous reviewers for insightful comments on an earlier draft and the Editor for prompt support. The usual disclaimer applies.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dutta, N., Kar, S. & Sobel, R.S. What influences entrepreneurship among skilled immigrants in the USA? Evidence from micro-data. Bus Econ 56, 146–154 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1057/s11369-021-00220-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s11369-021-00220-9