Abstract

In line with the new trend toward participatory city branding processes, this article offers four theoretical principles and practices that guide a communicative approach to city branding. Specifically, this article (i) theoretically explores how different voices of the city construct public perceptions of a city’s brand images and brand identities, and (ii) offers a conceptual methodology that marketers could use to engage, invite, listen and hermeneutically ‘read’ such discourses and narratives to reveal unique meanings of the city’s key attributes. Drawing on Ricoeur’s narrative theory, Hauser’s view of publics and literature from socio-spatial studies of urban branding, this article argues for a public-oriented understanding of city brands that focuses on the dialectical relationship between narrative and the symbolic meanings that publics attach to shared social spaces. This article supplements current city branding literature by exploring how public discourses and narratives form, enhance and communicate key meanings of the city, and how marketers can identify and integrate such understandings in communicating the city brand. A case study of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania’s discourses and narratives was then explored to unearth key metaphors of the city that marketers could – and what is argued should – be communicated as the city brand.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Through the ‘construction, communication and management’ of a city’s greatest attributes, city branding seeks to create a memorable and attractive brand (Ashworth and Kavaratzis, 2009, p. 507). Successful city branding campaigns draw tourists, residents, investors, businesses and potential residents to the region, thereby boosting the city’s economic and social prosperity (Anholt, 2007). Nonetheless, a common city branding pitfall entails affixing logos, slogans and advertising jingles to a place and calling it a ‘brand’ (Govers, 2013). To enhance a place’s attractiveness, marketers regularly use stylish slogans and pretty pictures without wholly understanding why these images resonate with so many different individuals (Kavaratzis and Ashworth, 2005; Ashworth and Kavaratzis, 2009). These quick-drawl campaigns may result in uncharacteristic descriptions and visuals (Parehka, 2011), leading to poor perceptions of the city’s realistic offerings (Trueman et al, 2007). Residents may reject derived city brands, publically attacking such choices via social media (Northdecoder, n.d.), fashioning counter-brands (Braun et al, 2010) or positing their own DIY (Do-It-Yourself) city brand versions (King and Crommelin, 2013). Concerns for how the intended city brand may be ill-represented in marketing messages and visuals, or how such efforts may be misinterpreted by audiences, point to the necessity of understanding how people perceive and communicate perceptions of a city in their everyday conversations and behaviors.

A review of current place branding literature suggests stakeholders’ communications play several significant roles in the place brand’s success or failure (Govers and Go, 2009; Braun et al, 2010; Kavaratzis, 2012; Klijn et al, 2012). Braun et al (2010) claim that current residents are even now ‘ “making or breaking” the whole marketing process’ (p. 3) through their daily discourses and behaviors. Kavaratzis (2012) reasons that ‘stakeholders are more than just customers or consumers of place brands for their actions legitimize the brand and heavily influence its meaning’ (p.7). Even when they are not formal members of the branding campaign, stakeholders actively create, sustain, confront and reinforce a city’s unique attributes through a variety of communication channels, for example, media commentaries, online discourses, word-of-mouth communications and through cultural or regional elements like language, food, dance, dress and so on. Yet, stakeholders are primarily treated as ‘passive beneficiaries’ of the marketing messages (Braun et al, 2010, p.2), being largely ignored in the initial stages of the branding process. Such literature suggests that marketers need to reevaluate how they identify what place brands mean to stakeholders and begin to engage stakeholders as informed and valuable assets for the construction and communication of place brands.

Several place branding scholars have turned toward a participatory approach that places stakeholders as central figures in the place branding process (Aitken and Campelo, 2011; Hanna and Rowley, 2011; Zenker and Seigis, 2012; Kavaratzis and Hatch, 2013). Such initiatives highlight the meaning-making function of discourse with diverse publics, whereby ‘multilogues’ of brand, cultural and environmental engagements contribute to the co-creation of place brands (Aitken and Campelo, 2011; Kavaratzis and Hatch, 2013). Driven by discourse and the strategic engagement of stakeholders, this literature set the precedent for transformative methodologies to integrative city branding practices that this article seeks to establish. In line with the new trend toward participatory discourse, this article offers theoretical principles and practices that guide a communicative approach to city branding. Specifically, this article (i) theoretically explores how different voices of the city construct public perceptions of a city’s brand images and identities, and (ii) offers a conceptual methodology that marketers could use to engage, invite, listen and hermeneutically ‘read’ such discourses and narratives to reveal unique meanings of the city’s key attributes.

Pivotal to this approach is the inclusion of spatially sensitive narratives that reflect how ‘places are represented by and intervened in according to a complex dialectics of socio-spatial relations’ (Jensen, 2007, p. 217). The basic premise here is that marketers already use cultural narratives to communicate desired opinions of the city (Jensen, 2007) and reframe negative perceptions of a place to promote physical and institutional change (Peel and Lloyd, 2008). While markers use narrative as a communication-promotional tool to circulate prescribed images and slogans of the city brand, multiple internal and external audiences give voice to their ideas of the city through the same means (Finnegan, 1998). Although these scholars have called for culturally driven, experience-oriented and spatially sensitive studies of place brands, the inclusion of a narrative framework for studying public perceptions of the city is largely missing from place branding theories. This article supplements current city branding literature by exploring how public discourses and narratives form, enhance and communicate key meanings of the city, and how marketers can identify and integrate such understandings in communicating the city brand.

To begin, city branding scholarship attending to communicative aspects of city brands will be addressed. Next, participatory branding theories are discussed. Ensuing is an overview of discourse and narrative analysis theories as they apply to urban branding. Subsequently, a communicative approach to studying a city’s tertiary communication practices, framed by public discourses and narratives, is described. Third, a case study of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania’s discourses and narratives are explored to unearth key perceptions of the city.

As a Rust Belt city, post-industrial Pittsburgh has continually sought to refashion and rebrand itself as a hip and entertaining place to visit and an economically and environmentally friendly place to live. These transformations have captured media attention and received international and national accolades in recent years, making this city’s discourses and narratives ripe to study. The author’s residency in this area from 2006–2013 further contributed to the observation of these transformations. Lastly, the metaphors that collectively form Pittsburgh discourses and narratives that marketers could – and what is argued should – be promoted as the city brand are explained. The article then concludes with a brief summary and discussion of limitations and implications for future research.

A COMMUNICATIVE FOCUS IN CITY BRANDING LITERATURE

Kavaratzis (2005) suggests that three types of communication exist that convey a city’s brand. Primary communication ‘relates to the communication effects of a city’s actions, when communication is not the main goal of these actions’ (ibid, p. 337). Primary communication involves the physical and strategic visions for a city designed by city planners, including: landscape strategies (urban design, architecture, public spaces), infrastructure projects (streets, facilities, monuments), organizational and administrative structures (government, citizenship, public–private partnerships, politics) and behavior (financial incentives, city planners’ vision, culture). Secondary communication serves as ‘the formal, intentional communication that most commonly takes place through well known marketing practices’ (Kavaratzis, 2005, p. 337). Tertiary communication is discourse by media, city residents and competition that is neither managed nor consciously controlled (Kavaratzis, 2005). In this regard, tertiary communication could be observed as the sharing of personal and public perceptions and stories about the city.

Using Kavaratzis’ work as a basis for their project, and building from Hatch and Rubin’s (2006) theory of hermeneutic branding, Peel and Lloyd (2008) include stakeholders’ interpretations of a city’s primary and secondary communication as key elements of the branding process. Through their analysis of stakeholders’ perceptions of Dundee, Scotland in relation to the city’s formal and deliberative communications, Peel and Lloyd (2008) describe a ‘communicative logic’ for city branding (p. 507). Communicative logic indicates the collective interpretation of the structural, infrastructural, landscape, governance and behavioral aspects of a city. The authors imply that a present theory of city branding should move toward convergence and integration of communicative logic and marketing strategies within a strong communication platform.

The latest work from Kavaratzis and Hatch (2013) ‘argue against the dominant communications-based view of place branding’ that treats the place brand as an outcome of ‘manageable and easily communicated’ elements pre-determined by those in decision-making positions (p. 74). This practice coincides with traditional views of place identity as the outcome of what place brand practitioners craft and communicate via marketing messages and visuals, with place image customarily seen as ‘the sum of beliefs, ideas and impressions that people have that place’ (Kotler et al, 1993, p. 141). Contrariwise, the authors follow Hatch and Schultz’s (2010) suggestion that ‘culture is the context of internal definitions of identity’ while ‘image is the site of external definitions of identity’ and ‘how these two definitions influence each other is the process of identity’ (quoted in Kavaratzis and Hatch, 2013, p. 77). In short, culture is how we see ourselves (in-group perspective), image is how others see the group (outsider perspectives) and identity is a mixture of the two. In conversation, these perspectives are shared, their meanings are re-examined and continually reframed. This article follows these definitions of culture, place image and place identity, agreeing with Kavaratzis and Hatch’s (2013) view of place branding as a process of ‘dialogue, debate, and contestation’ (p. 82) among divergent perspectives. Emergence of place branding scholarship that emphasizes the importance of participatory discourse to the construction of place brands further demonstrates that a turn from sender-oriented branding communications to public-centered and emergent communications about city brands are necessary.

PARTICIPATORY PLACE BRANDING – ESTABLISHING STAKEHOLDERS’ ROLES

In the corporate sector, the term ‘stakeholders’ refers to any individual, group or institution that affect and can be affected by an organization’s behaviors (Donaldson and Preston, 1995). For a city, internal stakeholders include residents, businesses, non-profits, governments, social groups and any individual with a ‘stake’ in the outcome of a city’s economic, structural, operational, political and cultural workings, and those who share in the benefits and drawbacks of such interactions. External stakeholders are potential stakeholders who may move to the city to live, travel there to work or visit (for a succinct overview of stakeholders’ roles within the city, see Kavaratzis, 2012). On one hand, the use of the term ‘stakeholders’ in place branding literature makes sense, as several scholars draw on corporate branding theories to build stakeholder relationships, communicate place identity and fashion strategic marketing messages (Ashworth and Voogd, 1990; Kotler et al, 1993; Rainisto, 2003; Trueman et al, 2007; Kavaratzis, 2009). On the other hand, the practice of treating city residents, visitors, social groups and so on as stakeholders reduces their involvement to mere consumers of spatial experiences and place resources, and trivializes the complex process whereby varied personal and public actions influence the health and well-being of places like a city. From a communications perspective, it may be more advantageous to refer to such groups as ‘publics’, as ‘all defining actions of a place brand take place in public’ (Kavaratzis, 2012).

According to communication scholar Gerard Hauser, our shared social spaces have a multitude of publics whose discourses and actions affect many aspects of public life, for example, governance, civic engagement, cultural and social interactions and community affairs. He defines publics as ‘the interdependent members of society who hold different opinions about a mutual problem and who seek to influence its resolution through discourse’ (Hauser, 1999, p. 32). This perspective reflects public relations approaches that similarly perceive publics as a consortium of individual members who come together to identify and organize action in response to a problem or issue (Gruing, 1992). Likewise, Braun et al’s (2010) characterization and classification of stakeholders as integrated place brand users, ambassadors and citizens distinguishes their actions and behaviors as significant contributions to the success and/or failure of place brand. This article shares these views and assumes the presence of multiple publics within a city whose opinions and actions contribute to a city brand’s reception.

Concerned that we gain our insights into publics and public opinion through too many empirical channels (predominantly polls, surveys and other scientific means), Hauser places discourse within public spaces, what he calls vernacular voices, at the forefront of studying the ways in which individual and groups arrive at and share their public opinions. Vernacular voices are ‘the ways by which publics make their presence known; and if we have to listen, these are the ways by which they make their opinions felt’ (p. 11). Hauser mentions several types of symbolic exchanges whereby individuals share their vernacular voices. ‘They [publics] are active and attentive to issues through all courses of interaction: capitalism, symbolic representation of opinion: yellow ribbons, banners, etc., public debates, and other expressions of stance and judgment’ (Hauser, 1999, p. 33). Hauser (1999) refers to subtle acts like yellow ribbons, flying the American flag in one’s yard or cause-related bumper stickers as publicness. Publicness denotes intentional actions in public spaces that are not outspoken gestures of public opinion but nonetheless demonstrate a person’s views on particular public issues. Hauser’s view of publicness supports this article’s argument that people demonstrate their attitudes toward the city in many ways, which may or may not include outspoken public communications. By examining discourses about the city, marketers can uncover how publics invest in a city’s rhetorical construct of culture and the self-generating and sustaining activities by which public opinions are produced and shared in the narratives people tell about the city.

DISCOURSES OF SPACE AND THE NARRATIVE TURN

Research into brand perspectives reveals that what people discuss in their discourse often becomes the foundation for constructing place brands. Studying the socio-spatial dialectics concerned with urban planning, Richardson and Jensen (2003) see brands as articulated expressions within discourse. To explain this concept further, Jensen (2007) notes, ‘Discourses are articulated in specific vocabularies, and transformed into social reality through the actions of social agents within institutional contexts’ (p. 216). Similarly, Peel and Lloyd’s (2008) work reveals the importance of hermeneutically interpreting brand perceptions, suggesting that a ‘sensitivity to a staged plurality of meanings is appropriate to an understanding of the complexity of city imagery and the different spatio-temporal contexts and constituencies of interests involved’ (p. 513). The idea that spaces are socially constructed through transfers of meaning in daily communication, and that many perceptions of the same physical space coexist, suggests the need to analyze how discourses about a space and strategies relating to the construction of brands are connected via the meaning-making activities related to particular spaces. Jensen (2007) advocates that these relationships are not just coincidental but essential for understanding the meanings that people attribute to the spaces that they inhabit. ‘Social agents give voice to ideas of spatial change in the city by means of local narratives and stories nested within discourses’ (Jensen, 2007, p. 218). This understanding necessitates a ‘narrative turn’ that does not focus on arduous analyses of spatial narratives but follows a set of hierarchical principals.

Jensen (2007) contends that narratives have several modes of representation that flow from textual, detached information (which include visuals) to structured narratives. Such narratives are then emplotted to form stories, which stem from larger, institutionalized discourses. Agreeing with Jensen’s observation that stories illustrate a sequence of events and plots structure that sequence for maximum impact and relevancy, this article, however, deviates from Jensen’s view that narrative subsumes to story. Jensen (2007) firmly asserts that the story provides perspective of the text or discourse while narrative is recitation of events. Conversely, this article follows Ricoeur’s (1984) view of narrative: ‘in the broad sense, defined as the “what” of mimetic activity, and narrative in the narrow sense of the Aristotelian diēgēsis’ (p. 36). Between showing someone our experiences through representational activity (mimesis) and telling them about our experiences (diēgēsis), Ricoeur reasoned that narrative was more than just the stylistic means by which stories are told; narrative serves as the temporal context through which meaning becomes the most clear.

To better understand our experiences, Ricoeur (1984) contended that we examine our actions through the rationalization and explanation of their occurrences – happenings – that are then (re)arranged and emplotted into a meaningful narrative that can be read or retold. The reading and the retelling give way to a dynamic understanding of our experiences that Ricoeur maintained could not be fully understood relying on internal reflection alone. When experiences are invoked by public discourse and shared as narratives within a public setting, significant symbols of culture, metaphors of discourse, are revealed.

Metaphors compare two words, ideas or phrases that are otherwise dissimilar, in familiar ways. ‘As a figure, metaphor constitutes a displacement and an extension of the meaning of words; its explanation is grounded in a theory of substitution’ (Ricoeur, 1977, p. 3). Metaphors are central to comprehending cultural symbols for they express experience and complex phenomena in easier-to-understand ways. In terms of their representational qualities, metaphors help people better recall their own experiences, construct deeper connections with others who share in the understanding of those experiences and craft collectively shared meanings (Ricoeur, 1977). In addition, metaphors speak to a larger group of individuals when they identify and direct meanings that hold value for particular groups (Hauser, 1999). When placed in a narrative framework, metaphors stimulate deep and often latent perceptions, feelings and attitudes toward the plot, characters and/or their actions (Ricoeur, 1984). In regards to the city, applying a hermeneutical investigation to city discourses and narratives told by internal and external publics could unearth prominent and profound metaphors for the city. Investing in the discourses of the city’s publics may then help marketers parse these significant metaphors as the foundations for a strong city brand.

Whereas studying narratives within public spaces leans more toward an empirical paradigm, the examination and implication of messages within a city’s and its public discourses demands a communicative approach. A communicative approach to narrative attends to how individuals and groups communicate their experiences with the city and how they understand their public roles in influencing perceptions of the city. Moreover, socio-cultural inquiries emphasize the relationship between social patterns and factors, and the sociological consequences of a narrative’s telling/retelling within public spaces, which is beyond the scope of this project. Instead, this article invites marketers to think thoroughly and extensively about what aspects of publics’ needs and wants are fundamental to their perceptions of the city, and how those considerations are communicated in the public sharing of experiences via discourse and narrative. Thus, this article argues for a public-oriented understanding of city brands that focuses on the dialectical relationship between narrative and the symbolic meanings and metaphors that publics attach to shared social spaces.

THEORETICAL PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICES OF A COMMUNICATIVE APPROACH

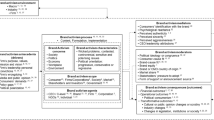

On the basis of a synthesis of the given literatures, this research suggests four principles that guide marketers’ discursive practices and provide a theoretical base for intelligent reflection of public discourses and narratives about the city: meaning matters: listen to vernacular voices; a plurality of publics exists: practice invitational rhetoric; cities have three dimensions: texturize meaning; and narratives are not just embodied but embedded: become a narrator of the city’s stories. The practices that emerge from these principles do not follow any prescribed ‘rules.’ Rather, this unique conceptual methodology bridges social science practices with philosophical theories in ways that hold significance and meaning for all those involved in the branding of a city’s images and identities (see Figure 1).

Meaning matters: Listen to vernacular voices

Individuals and groups often have personal and/or public identities that are deeply tied to the city’s identities (Kavaratzis and Hatch, 2013). In addition, personal and/or collective experiences of the city pilot perceptions that influence how individuals and groups communicate what the city means to them. The meanings behind people’s perceptions matter, and to better understand this phenomenon, a hermeneutic reading of vernacular voices is necessary. Within the hermeneutic branding tradition, studying the ways in which people use their physical and social environments could help to identify how people acquire and craft meaning in their lives (Douglas and Isherwood, 1996; Hatch and Rubin, 2006). Marketers can practice hermeneutically reading vernacular voices by listening to social conversations and observing publicness as they occur in everyday public settings.

Public settings not only refer to physical areas where people gather in aggregate, like city parks or the downtown region, but can also mean virtual spaces. More and more people are using social media sites like blogs, Websites and web videos to share their vernacular voices, meaning that these public forums offer wide range, interactive platforms for collaborative social engagement and information sharing (Kavaratzis 2012; King and Crommelin, 2013). Furthermore, marketers should conduct ethnographic observations of the ways in which people interact with the city, that is, their publicness (for an approach to this methodology, see Aitken and Campelo, 2011). Subsequently, marketers ought to take note of the specific rituals or behaviors that resonate with multiple publics.

Listening to vernacular voices as they emerge from everyday public discourses will provide additional insight into how their experiences with and within the city come to have meaning in their personal and public lives. Correlating patterns between these qualitative and quantitative measures of public opinions can then better inform ‘the potential active interplay’ (Peel and Lloyd, 2008, p. 507) of a city’s primary, secondary and tertiary communication practices in ways that have yet to be fully studied.

A Plurality of publics exist: Practice invitational rhetoric

Marketers often intently curb their marketing efforts to tourists. While tourism is a booming industry for many cities, cities endure economic and physical hardships through their residents, businesses and groups who have a stake in its well-being. A plurality of publics exists (Hauser, 1999), and as such, the city branding process should seek to include informed opinions of all those whose speech and deeds have often indirect, but nevertheless, important influence on the city brand. In short, the branding process must extend beyond the ‘usual suspects’ to include the vernacular voices of multiple publics. Being attentive to a plurality of publics depends on marketers inviting people to share their thoughts on what the city means to the them, and then including such salient meanings within a branding campaign that is attentive to building strong relationships and maintenance of shared social interests relevant to a city’s spaces.

First proposed by Foss and Griffin (1995), invitational rhetoric focuses on engaging, rather than persuading or controlling, individuals to reveal their perceptions in discourse. The goal of invitational rhetoric is ‘to enter into a dialogue in order to share perspectives and positions, to see the complexity of an issue about which neither party agrees, and to increase understanding’ (Bone et al, 2008, p. 436). In unassuming yet analogous ways, invitational rhetoric offers a framework through which individuals and groups can be invited to share their motivations and reasons for participating in public discussions about the city. Creating a safe environment for people to share their opinions results in enhanced understandings of the topics involved and discovery of new knowledge, beliefs or issues (Foss and Griffin, 1995). This parallels Ind and Bjerke’s (2007) view that a participative approach to brand building should include ‘regular meetings with customers in an environment that is both social and businesslike’ (p. 138). Creating a safe place involves both a welcoming attitude and displays of authentic empathy to hear what the other person has to say in the conversation. Inviting others into a conversation free of restrictive boundaries also opens up spaces for a coalition of public opinions that are sensitive, responsive and respectful to multiple individual and collective concerns. Hauser (1999) writes, ‘Understanding people’s concerns and why they hold them holds promise for helping leaders to communicate with society’s active members rather than manipulating them’ (p. 265).

Since there are multitude of publics and their participation in public discourses may occur in many divergent ways, a communicative approach to city branding would include several processes of civic engagement that neither neglect the marginal voices in society nor force anyone’s participation. Social media and the Internet provide a space where marketers and city planners can invite people to anonymously share their opinions and images of the city or become very vocal and active participants. A downside to using social media may be further marginalization of voices that do not have access to such channels. Those who do not have access to mediated forms of communication can still have their voices heard if marketers use traditional forms of communication.

Marketers need to become a part of the discourses that they are wishing to study. Many practices that are at the heart of a city’s brand images and identities could easily be overlooked from behind a computer screen or by simply studying quantitative opinion polls. Going out into the communities and inviting people to attend focus groups, holding impromptu interviews or posting fliers in high-traffic areas may help mitigate access issues. To find a consortium of different public opinions, marketers should attend public events and visit tourist spaces. Marketers need to keep in mind, however, that they are not tourists either, but have been charged to facilitate and enhance the city’s most unique and endearing qualities. As the city’s geography, government, economy and so on change, marketers need to continually reassess and collaborate with various publics to evaluate current marketing practices and conduct new research to determine the possibilities for a city to realistically achieve given a limited amount of time and/or resources.

Cities have three dimensions: Texturize meaning

Understanding that cities are different from corporations, products and services is an important concept to consider when promoting a dynamic entity like a city. Ashworth and Kavaratzis (2009) argue that marketers ‘too easily assume that places are just spatially extended products that require little special attention as a consequence of their spatiality’ (p. 507). Cities have three dimensions: (i) physical dimensions: buildings, parks, bridges, lakes and rivers, infrastructure and so on where public activities occur; (ii) perceptual dimensions, or cities as they cognitively exist; and (iii) social dimensions: historical and cultural heritages, social norms or ways of interacting in public settings and organizational structures that govern exchanges within shared spaces. The mulitple contexts and dimensions that a city must theoretically become for multiple publics presses upon city marketers that the messages of a city’s branding efforts must also become more complex and stylish. To attend to a city’s dimensionality, marketers can texturize the city branding campaign by including metaphors of the city’s unique characteristics.

Metaphor’s ability to present understanding and explanation in a single utterance offers considerable illustrative advantages to marketers given the minimal contact time that brand images and messages have with consumers, but only if the recalling of such images and metaphors are favorable. Biel (1993) contends that strong visual metaphors evoke a more extensive, richer set of associations that increase brand value. Visual metaphors ‘provide a powerful set of symbols’ that are important to an individual’s memories of that image (Biel, 1993, p. 73). In 2006, Laaksonen et al asked focus group individuals to create visual collages of what images they thought best represented Vassa, Finland. From their discussions, Laaksonen et al determined three levels – observation, evaluation and atmosphere – through which a city image can be classified. These levels are further broken down into images related to built environments and nature (that is, primary communication), culture and industry. In a separate but parallel approach, this project asks marketers to be attentive to multidimensional metaphors that emerge from patterns of shared meaning within public discourses and narratives, and include the metaphors that attend to the three types of a city’s dimensionality in their secondary communications. Moreover, marketers need to become more aware of when their messages or visuals teeter toward over-embellished language to the point that internal publics no longer believe the metaphor. Without resemblance to the tertiary communication efforts of a city’s internal publics, the imposed images and messages of a city’s secondary communication efforts may fail to create loyalty toward, and therefore a long-term investment for, the city brand.

Narratives are not just embodied but embedded: Become a narrator of the city’s stories

Narratives are not just embodied in culture, they are embedded in personal and public identities that reinforce and reflect city brand identities. As such, city branding efforts must also become embedded in cultural narratives. Marketers can express authentic experiences of the city’s publics and become narrators of the city’s stories when they emplot main expressions and metaphors of the city in their branding campaigns. To promote a dynamic entity like the city, the dialectical balance between belief in the imageries projected by the narratives (imagination), and the experience of and interactions with a city’s physical and metaphysical environments (reality) must be sustained. To this end, this article encourages ethical responsibility toward narrative imagination and the refiguration of experiences in the metaphorical language and mental imageries used to promote the city. Moreover, a good narrator pays attention to how the listener responds to the story and may change the plot’s direction or emphasize an appealing point so that the narrative remains attractive to the audience. This understanding coincides with re-evaluating and changing the narrative when the city and its publics change.

A communicative approach to the promotion of a city values how public perceptions collectively give shape to a city brand. The rhetoric of everyday conversations and interactions point to spaces where larger, communally sustained consciousness are available, where people engage the city brand, and where people use discourse to build a web of significance for their daily interactions. These forms of tertiary communication also reveal public sentiments toward primary and secondary communication efforts beyond mere public opinion polls. From the reading of vernacular voices, patterns will emerge that indicate what terms, visuals or messages could be main metaphors for a city’s brand. Marketers can then texturize and narrate prominent metaphors associated with a city’s dimensionality in their secondary communications, making sure to have ethical responsibility toward what meanings those practices convey. To demonstrate this connection in more detail, hermeneutical analyses of discourses and narratives about Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania have been explored.

METHODOLOGY

Utilizing the first and second principles, practicing invitational rhetoric and listening to vernacular voices, this project hermeneutically investigated public discourses and narratives of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania as they emerged from semi-structured interviews and ethnographic observations of the city and its publics over a 1-year period from 2012 to 2013. Relying on word-of-mouth from a web of interpersonal connections, the author first asked city residents to share their opinions of the city, who then asked people they know to share their perceptions. By attending public events and engaging in conversations in public areas around the city, the author asked other publics like visitors, business owners and and government officials to share their perceptions about Pittsburgh. To invite more voices, the author posted a call on Twitter and Facebook for people to share their stories about Pittsburgh. This message was then circulated via followers of those sites. Individuals who agreed to share their opinions of Pittsburgh were then contacted for a more in-depth interview.

Unexpectedly and unintentionally, those who responded to the call and participated in the interviews (N=27) had different relationships to the city: residents, visitors, former residents, local government employees and business owners. Each participant was asked, (i) ‘What makes Pittsburgh, “Pittsburgh”?’ (ii) ‘What metaphors or images would or should represent Pittsburgh as a brand?’ (iii) ‘Do you have any stories about your experiences in Pittsburgh that paint the clearest picture of the city’s identity in your mind?’ These open-ended questions were asked to gain a deeper understanding of the meanings that individuals ascribe to their experiences and perceptions, and allow participants to elaborate on their descriptions in more detail. Information from historical sources, newspaper and scholarly articles, as well as discussions from Pittsburgh-themed blogs like pghbloggers.org and IheartPgh.com, were further included as demonstrations of significant public discourses. All collected data was openly coded to identify repeated themes, terms or ideas that could function as prominent metaphors for the city.

Once known for its steel industry, the city of Pittsburgh has undergone a rejuvenation process after many of its mills permanently closed in the mid-to-late 1980s. Trying to overcome previous images as the ‘dirty’ or ‘smoky’ city, Pittsburgh city planners planted trees along city streets, built several green buildings and created four sizeable parks within the city limits. The city has also promoted its entertainment, medicinal and educational sectors to drive ‘A New Pittsburgh.’ Although Pittsburgh has a lengthy and varied history and could be known simply for its steel, rivers and bridges (its physical dimensions), this article focuses on perceptions of the city as corroborated from Pittsburgh’s publics’ Dahntahn discourses and neighborhood narratives. The findings from this study are then used to describe how marketing practitioners can texturize meaning and narrate Pittsburgh’s, and its publics’, stories in their city branding campaigns.

DAHNTAHN DISCOURSES

Pittsburghers affectionately call their city center ‘Dahntahn’ – a term that stems from a cultural vernacular, Pittsburghese. Pittsburghese is a form of the English language where words are blended together to form expressions. Johnstone and Baumgardt (2004) remark that in the late 1960s to mid-1970s the grandchildren of immigrant workers no longer wanted to be associated with their ethnic vernacular and instead developed a language based on ‘class and regional consciousness’ (p. 120). A Pittsburghese ‘quote’ might be: ‘I’m goin’ Dahntahn to buy some pants n’at and eat a Primanti’s (pronounced Per-man-tees) san’wich’ (Kaitlin Wingard, 2013, Interview). This translates as: ‘I am going Downtown to buy some pants and other things and eat a Primanti’s sandwich’ (a Pittsburgh cuisine creation that places vinegar-based coleslaw and fries directly on the sandwich). Other common sayings include: slippy (slippery), nebby (nosy) and jagoff (a derogatory term for someone acting inappropriately). Although Johnstone and Baumgardt claim that this dialect is not exclusive to Pittsburgh, nor does it constitute the only language for the Pittsburgh region, the vernacular helps to identify one of Pittsburgh’s most distinguished characters.

Born and raised in Pittsburgh, a Yinzer is ‘Someone from the area east of Ohio, west of Philly. Speaks Pittsburghese. Drinks IC [Iron City Beer]. Loves the Stillers [Steelers], yinz guys. Says “jeet yet” to see if you’re hungry, calls downtown “Dahntahn.” Two of my best friends are “Burghers.” Good, salt of the earth people’ (Michael Myers, 2012, Interview). Yinzers are typically characterized by their language and reference to the second-person plural ‘yinz’ or ‘yunz’ similar in use to the Southern ‘ya’ll’ (Johnstone and Baumgardt, 2004). While some may consider those who use this vernacular uneducated, others find humor and a deep connection to Pittsburghese. Perhaps this is why people still refer to Downtown as ‘Dahntahn’ and put Pittsburghese sayings everything from t-shirts and bumper stickers to shot glasses and Web parodies.

King and Crommelin (2013) contend that Pittsburghese and the Yinzer could be seen as unofficial representations of Pittsburgh’s urban brand. More specifically, the Webisode series, Pittsburgh Dad, functions as a form of ‘DIY’ urban branding, what King and Crommelin (2013) call the yinzernet, that showcases Pittsburgh’s ‘place character’ or ‘a set of patterns in meaning and action that are specific to a distinct locale’ (Paulsen, 2004, p. 245). Created by Curt Wootton and Chris Preksta, the 1–2-min clips feature a character called Pittsburgh Dad whose mannerisms and speech illustrate the main characteristics of a yinzer. In one Webisode, the Pittsburgh Dad becomes angry with his children when they disrupt his favorite pastime, watching Stiller (Steeler) football. Showcasing his Pittsburghese, the Pittsburgh Dad character yells, ‘Hey yunz kids, quit stompin’ on them floors up arh! I’m tryin to watch da game!’ (Pittsburgh Dad, 2011). ‘These yinzernet representations focus on blue-collar and folksy aspects of the local culture, suggesting a possible cultural mismatch with the hip, white-collar, post-industrial image promoted by formal city branding efforts’ (King and Crommelin, 2013, p. 265). Comical and quite sensationalized, the authors argue that the yinzernet neither responds to nor rejects the city’s secondary communication efforts, which highlight Pittsburgh’s economical and image shifts toward technology, entertainment and education; rather, this form of DIY place branding demonstrates nostalgia for Pittsburgh’s cultural heritage not represented in the city’s two most recent city branding campaigns.

The city’s 2007 campaign, ‘Pittsburgh: Imagine What You Can Do Here,’ (www.imaginepittsburgh.com) asked people to envision how they can live, work and play in the city’s rivers, green parks, museums and entertainment venues. This campaign sought to revitalize the riverfront by presenting pictures of people canoeing, fishing and boating along Pittsburgh’s three rivers. The campaign also featured Pittsburgh’s sports stadiums, PNC Park (home of Pittsburgh’s MLB team the Pirates) and Heinz Field (home of their National Football League, Pittsburgh Steelers), which offer stunning views of the river with Dahntahn’s skyline serving as a backdrop. For the 2012 ‘Pittsburgh: Here+Now’ campaign, marketers drew attention to Pittsburgh’s downtown region (pittsburghnow.org). In comparison to mega metropolises like New York or Los Angeles, Pittsburgh’s downtown region does not boast an all-night scene, but does have affordable housing, many upscale and to-go restaurants, chic boutiques and large-scale shopping centers like Burlington and Macy’s. Then-Mayor Luke Ravenstahl sought to make Dahntahn a ‘vibrant 24/7’ location, so the campaign displayed images of the Cultural District, a downtown area that houses many theaters: the Benedum Center, Byham Theater, O'Reilly Theater; music halls like Heinz Hall; and galleries like the Wood Street Galleries (www.walltowall.com). According to King and Crommelin (2013), ‘This campaign focuses explicitly on downtown rather than the neighborhoods, promoting an urban lifestyle of eco-friendly loft-living, bicycle commuting, shopping, entertainment and technology-based business opportunities’ (p. 268). Although Pittsburgh’s past branding efforts attend to the city’s physical and social dimensionalities by highlighting how the Pittsburgh’s landscape augments and heightens commerce and entertainment in and around the city, their campaigns may be ignoring a very vibrant and unique segment of the Pittsburgh region.

Pittsburgh is a city of neighborhoods. This claim is made by many cities that celebrate their traditional enclaves, but Pittsburghers seem more attached to their places than other folks in other places. It is common for natives to define their home not by city boundaries, but by neighborhood boundaries, and many are reluctant to cross rivers or go through tunnels, of which the city has many. (The New Colonist)

This statement reflects a common response from interviewees and online discussions. A macro assessment of these discourses reveals that the majority of Pittsburgh’s perceptual dimensions stem from personal connections to the city’s neighborhoods.

NEIGHBORHOOD NARRATIVES

Discourses of city residents revealed that where a person lives in the city is very important to their private and public identities. Each of the nearly 90 Pittsburgh neighborhoods embodies unique qualities that express the cultural stories of that neighborhood and its residents. This understanding became very apparent when viewing a DVD titled, Greetings from Pittsburgh: Neighborhood Narratives (2008a). Produced by local Pittsburghers, the nine fictional stories in Neighborhood Narratives represent some of Pittsburgh’s most culturally diverse and heavily populated neighborhoods: Southside, Strip District, Downtown, Oakland, Lawrenceville, Bloomfield, Homestead, Hill District and Regent Square. Co-creators of the project Andrew Halasz and Kristen Lauth Shaeffer wanted each short film to ‘provide a unique portrait of the communities through fictional personal stories that reveal the experience and character of the neighborhoods in which they take place’ (Greetings). Each story, albeit fictional and written from the perspective of individual filmmakers, fittingly captures the distinctive attributes and significant metaphors of each neighborhood.

Some films illustrate historical transformations of the city. Various ethnic groups settled in regional spots around the city and their heritages still influence that neighborhood’s restaurants, dress, vernacular and social habits. Neighborhood Narratives’ filmmaker, Timothy R. Hall, grew up in the Hill District and used a ‘pseudo-biographical’ photomontage of the Hill’s historical transformation to tell his story ‘What Green Could Be.’ On the film’s blog, film editors Halasz and Shaeffer state, ‘The Hill, as it is fondly known in the burgh, was once considered to be the center of African-American culture, steeped in art, literature and music. A decline in the steel industry, however, and the construction of the Civic Arena forced many residents to leave the neighborhood in the 1960s. Today, the area is slowly being revamped.’ Hall’s narrative, alongside the short film, ‘Notes in the Valley,’ connects the industrial histories of Pittsburgh’s Hill District and Homestead neighborhoods to the city’s current sustainable efforts.

Some films portray eclectic, and at times humorous, city rituals. ‘Milk Crate’ depicts the Southside ritual of claiming one’s parking spot with an object of some size, like a milk crate or chair. This ritual is a regular occurrence for the parking-plagued streets of the Southside but occurs throughout the city during the winter months when residents have to shovel their way out of on-street parking spots. In a personal interview, Sandra Shelly (2012, Interview) said, ‘you know its winter [in the city] once the chairs come out.’ Filmmakers Jeremy Braverman and Nelson Chipman’s film about Regent Square’s ‘porch parties’ comically illuminates how an anti-social New York businessman finds himself surrounded by nice neighbors. Braverman says, ‘We talked to people from the neighborhood and shared our favorite stories, things that were unique to Regent Square … A lot of that stuff found its way into our film, such as the front porch happy hours. Those are pretty big around here’ (Greetings).

Some films showcase neighborhood demographics. One film emphasizes the ‘youthfulness’ of Oakland, which is home to over 27 000 undergraduate students from University of Pittsburgh, Carnegie Mellon and Chatham University. In a personal interview, Lori Robinson (2012, Interview) recalls her time as a student in Oakland:

The area was very culturally diverse because of the universities. I did notice that African Americans, Jamaicans, Haitians and whites mixed freely but the Asian cultures stayed within their cultural groups and often only spoke their native languages. I think this part of the city was different because we [students] felt like it was ours because it was mainly students everywhere.

Ray Werner’s short film, ‘Tommy and Me,’ tells the emotional story of the Strip District’s two-sided personality. During the day, the Strip is home to the city’s largest open-air markets, but at night, the side streets are home to many of Pittsburgh’s homeless population. In the film, the character nicknamed the ‘Steeler Santa’ (attributed to the Santa hat and old Pittsburgh Steeler’s football t-shirt that he wears everyday), encourages crowds to shop at the nearby Mike Feinberg’s Novelty Shop. Rather than being a nuisance, the Steeler Santa’s continual presence in front of the shop became an asset to selling the merchandise, and his death in the film depicted how deeply his connection to the store and the city went. Upon hearing that all the proceeds from Neighborhood Narratives would go to Operation Safety Net, a medical outreach program for homeless individuals, The Steeler’s Organization granted permission for Ray to film a clip at their stadium.

The nine filmmakers in this collection claimed that their inspiration came from personal experiences, observations and memories of the city. Through their films, they not only narrated how Pittsburgh’s three dimensions – physical, perceptual and social – shape what this city means to them; they also captured the very essence of this city. Wanting to ‘give voice to our individual neighborhoods, and foster feelings of connectedness between all members of all Pittsburgh communities’ (Greetings), each film pays tribute to this region’s diverse vernacular voices and the ways in which Pittsburghers enact their publicness. The fitting way in which the DVD aptly captures Pittsburgh’s distinctive narratives, rituals and characters is evident by Pittsburgh publics’ receptions to the film. Greetings from Pittsburgh: Neighborhood Narratives’ first showing occurred on 25 September, 2008b, selling out to a full crowd in Regent Square. Similar comments by interviewees and hermeneutic investigations of Pittsburgh’s publicness correspondingly revealed that while each neighborhood had their own symbolic cultural cues, what forms people’s connections with each other and the city is the small town, inclusive feeling that Pittsburgh’s neighborhoods project even among 306 000 residents.

WON’T YOU BE MY NEIGHBOR?

For over 33 years, Fred Rogers asked viewers of his show Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood if they wanted to be his neighbor. Largely based from Mister Rogers’ time living 40 miles outside of Pittsburgh in Latrobe, PA, this show taught children about the value of friendship, honesty and lending a helping hand to one’s neighbors. Similar characteristics were described about Pittsburgh, with several respondents claiming how unique the neighborhood or ‘hometown feel is to a city these days’ (Jon Ford, 2013, Interview). When discussing how closely tied individual identities are to neighborhood identity, Rick Sebak, producer and director for WQED, notes, ‘People can’t believe that you don’t know their neighborhood.’ He then tells a story about a woman whom he was supposed to meet in Crafton (a small suburb of Pittsburgh) for an interview:

This was back before GPS. I asked her ‘How do I get to Crafton?’ and she tells me to first go to the Crafton-Ingram Shopping Center. I say that I don’t know where the Crafton-Ingram Shopping Center is and she says, ‘you don’t know where the Crafton-Ingram Shoppin’ Center is?!’ like I have two heads or something. (2012, personal communication)

Telling anecdotes of Pittsburgh’s publics and public spaces is a common occurrence for Rick, who self-identifies as the ‘narrator’ of Pittsburgh’s stories. For the last 25 years, Rick has narrated the majority of WQED’s documentaries about Pittsburgh and surrounding areas. When asked about residents’ loyalties to their neighborhoods, or even Pittsburgh in general, Rick commented, ‘Its’ not just regionalism, it’s something more … The emphasis [on neighborhood pride] is that many people are proud to call Pittsburgh home’ (2012, personal communication). ‘Home’ was a term repeatedly appearing in interviews, blogs and articles, indicating that this term may be a metaphor that signifies a significant perceptual dimension for this particular city. Another reoccurring term, ‘friendly’ may help to identify why many diverse people call Pittsburgh ‘home’ even when they no longer live in this city.

Bob Jones, a marketer who grew up in Swissvale but now lives with his wife in Los Angeles, was asked, ‘what makes Pittsburgh, “Pittsburgh”?’ He responded:

The thing that is most characteristic of Pittsburgh is that it is home to so many people. When you ask someone where they are from or ‘Why do you live in Pittsburgh?’ someone from Pittsburgh will say, ‘Where else would I live? That’s where I live.’ If you ask someone why they are in D.C. or L.A. they say ‘career’ or ‘five year plan and if I have accomplished this, this is my next goal ...’ Very few people would say, ‘This is my home, where else would I live?’ (2012, personal communication)

When asked what he means by ‘home,’ Bob elaborated, ‘I think what it means is that it is some place where you always feel comfortable. Where you feel home. People are so nice and so friendly,’ he paused and said again, ‘Because people are so nice and friendly.’ These statements provide some insight into why Pittsburghers feel the way they do about their city, and how the neighborhoods contribute to favorable perceptions about the city. The secret of Pittsburgh’s neighborhood charm, though, has been exposed.

In 2010, Pittsburgh was ranked one of ‘America’s Most Livable Cities’ (Levy, 2010) based on income growth rate over a 5-year span, everyday costs versus income, crime reports, thriving local culture and the number of colleges or university located in the city. In 2012, resident Christine O’Toole nominated Pittsburgh for National Geographic Intelligent Traveler magazine, ‘20 Must-see Destinations,’ for ‘its natural setting that rivals Lisbon and San Francisco, a wealth of fine art and architecture, and a quirky sense of humor’ (O’Toole, 2011, paragraph 6). Pittsburgh won this distinction, making this city one of only two US destinations, the other being Sonoma, California. That same year, Pittsburgh received an accolade as America’s ‘Hippest City’ (Judkis, 2012). Of these awards, Rick stated, ‘Pittsburgh has a little glow and no one thinks we don’t deserve it, but Pittsburghers don’t think of themselves as Seattlers or Portandlers, New Yorkers ... Pittsburgh is the hippest city on earth. In order to be “hip” you have to have no pretensions of being hip’ (Rick Sebak, 2012, Interview). These awards were given to Pittsburgh by mass media, but their meanings have been embraced and passed on by public discourses. Resident Susan Sternberger, who identifies herself on a Pittsburgh blog as ‘Proudly from Pittsburgh,’ wrote:

Please don’t tell too many people about this great city with it’s Gallery Crawls, Art All Night, Broadway shows, Three Rivers Arts Festival, First Night Celebrations, rabid sports fans, and the most genuine people you may ever come across. Oh, and the Chairs to reserve your parking spot once you’ve shoveled it out. Quirky? Yeah ... and proud of it.

Media labels and awards come and go like late March Pennsylvania snow; what remains are publics’ descriptions like ‘friendly’ and ‘home’ that support such accolades. These terms remain distinctive because Pittsburgh publics’ everyday actions, vernacular and publicness lend authentic and unpretentious attributes to this post-industrial city.

DISCUSSION OF PITTSBURGH’S CITY BRAND

Following the four principles that govern a communicative approach to city branding, this study revealed that Pittsburgh’s current city branding efforts focus on the physical and social dimensions of the city, but need to include more perceptual dimensions, specifically those relating to the city’s neighborhoods and the communal feeling of belonging (that is, feeling at home). Listening to the city’s vernacular voices, inviting personal narratives and conducting ethnographic observation of Pittsburgh’s publics, this study unearthed metaphors that should be used to texturize the city’s secondary communication marketing efforts. These include: Pittsburghese and yinzers (metaphors for place character), dahntahn (entertainment metaphor that could also serve as a homage to cultural and vernacular discourses), neighborhoods (either through images that signify unique rituals, traits or attributes of each neighborhood – like chairs on the street or porch parties – or through stories shared by Pittsburgh residents) and most livable city (highlighting which aspects make Pittsburgh the most livable). Although this last metaphor additionally serves as a slogan that frames Pittsburgh as a hip and modern cultural enclave, it also encourages perspectives of Pittsburgh as an economical and sociable place to call home.

It should be noted that these are not the only metaphors that fit Pittsburgh and there are many more narratives about the city that have yet to be told, ones that influence the city’s form and function and influence public perceptions. The metaphors presented in this study where chosen because they frequently appeared in public discourses and attend to the city’s dimensionality. These metaphors also stem from larger, more inclusive discourses and stories about the city, indicating that several overarching narratives exists for the city of Pittsburgh, narratives that many of its publics ‘bought into’ and embrace in their daily lives and interactions.

By texturizing secondary communication efforts, that is, constructing Pittsburgh’s city brand, with these metaphors, marketers can evoke cultural and personal memories of the city, theoretically becoming narrators of the city’s narratives. Once marketers listen to and engage Pittsburgh’s publics, they will better understand the vernacular voices that shape public opinions about its city brand. Only then can they begin to construct narrative threads that provide Pittsburgh with not just a strong brand but also a strong communal voice.

CONCLUSION

A city’s brand involves intricate interactions of complicated personal and public matrixes of expectations and attitudes about the city held by individuals and groups whose roles in forming these perceptions are equally as convoluted. As participation-centered branding processes gain importance in place branding literature, city marketers need to become aware of how individuals and groups represent the city in their communication practices. This article calls for a communicative approach that pays attention to the ways in which multiple audiences voice their opinions and emphasizes cooperative discourse in the fostering of city brands.

A communicative approach to city branding listens to many diverse voices and narratives and invites an inclusive discourse to the city branding process. This philosophy and its practices are based on the underlying premise that city branding is most effective through informed and transparent engagement with publics. Such an approach keeps marketers focused on the outcomes they are best suited to influence, yet remain attentive to all publics’ needs. Correspondingly, it prevents marketers from focusing too narrowly on primary or secondary in their promotion of cities, realizing that each play a strong role in a city’s supporting and responding to publics’ tertiary communications about the city.

Utilizing the four principles of a communication approach, the case study of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania presents not a consensus of public opinions on the city but a hermeneutical identification of the many ‘rhetorical possibilities and performances it can sustain’ (Hauser, 1997, p. 278). More than just becoming a hip and modern green city, the city pulled itself out from the soot of the Rust Belt to become a more economically feasible, friendly and folksy place to live. Besides their accolades, Pittsburgh’s eclectic and ethnic neighborhoods present narratives of an inherited culture and tradition that are not situated in a static past. Through an inclusive vernacular, Pittsburgh offers a sense of belonging to city residents and for people who no longer live there but still call Pittsburgh ‘home.’

Future research into this vibrant city would explore responses to the city’s current branding campaign, ‘PLANPGH,’ which promotes ‘an open and inclusive process focused on public participation’ and ‘finding common threads among people and the places they care about’ (planpgh.com). Forthcoming research would ask: How are Pittsburgh city planners and marketers using the information they garner from this form of participation? Are they using other communication channels beyond social media – for example, civic engagement, ethnographic narratives and observation of publicness – in their research? Literature relevant to stakeholders’ identity theories might help show such a connection. Limitations to a communication-based theory emerge from validity and generalization concerns related to the use of qualitative analyses. To insure viable representative samples of public opinions while providing the flexibility to permit trends, movements and stories to evolve, marketers could use a combination of qualitative and quantitative measures. The ideas and opinions represented in this article are informed by a praxis approach to the promotion of the city that moves beyond the mere branding of a city to the promotion of the city as a living, breathing network of organizations, people and ideas that project a multitude of voices, resounding in discourse and narrative. Isn’t that, after all, how we feel about the places we call home?

References

Aitken, R. and Campelo, A. (2011) The four Rs of place branding. Journal of Marketing Management 27 (9-10): 913–933.

Anholt, S. (2007) Competitive Identity: The New Brand Management for Nations, Cities and Regions. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Ashworth, G.J. and Voogd, H. (1990) Selling the City: Marketing Approaches in Public Sector Urban Planning. London: Belhaven Press.

Ashworth, G.J. and Kavaratzis, M. (2009) Beyond the logo: Brand mangagement for cities. Brand Management 16 (8): 520–531.

Biel, A.L. (1993) Converting image into equity. In: D.A. Aaker and A.L. Biel (eds.) Brand Equity & Advertising: Advertising’s Role in Building Strong Brands. Michigan, Hillsdale, NJ: L. Erlbaum Associates, pp. 67–82.

Bone, J.E., Griffin, C.L. and Scholz, L. (2008) Beyond traditional conceptualizations of rhetoric: Invitational rhetoric and a move toward civility. Western Journal of Communication 72 (4): 434–462.

Braun, E., Kavaratzis, M. and Zenker, S. (2010) My city – My brand: The role of residents in place branding. Paper presented at the 50th European Regional Science Association Congress, Jönköping, Sweden, http://www.ekf.vsb.cz/projekty/cs/okruhy/weby/esf-0116/databaze-prispevku/clanky_ERSA_2010/ERSA2010finalpaper262.pdf, accessed 12 January 2014.

Donaldson, T. and Preston, L.E. (1995) The stakeholder theory of the corporation: Concepts, evidence, and implications. Academy of Management Review 20 (1): 65–91.

Douglas, M. and Isherwood, B. (1996) The World of Goods: Towards an Anthropology of Consumption. New York: Routledge.

Govers, R. (2013) Why place branding is not about logos and slogans. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 9 (2): 71–75.

Govers, R. and Go, F. (2009) Place Branding: Virtual and Physical Identities, Glocal, Imagined and Experienced. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Greetings from Pittsburgh: Neighborhood Narratives. (2008a) Producers Kristen L. Shaeffer and Andrew Halasz. DVD.

Greetings from Pittsburgh: Neighborhood Narratives. (2008b) Blog Site. 18 September, http://pghneighborhoodnarratives.blogspot.com/, accessed 21 September 2012.

Gruing, J.E. (1992) Excellence in Public Relations and Communication Management. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Finnegan, R. (1998) Tales of the City. A Study of Narrative and Urban Life. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Foss, S.K. and Griffin, C.L. (1995) Beyond persuasion: A aroposal for an invitational rhetoric. Communication Monographs 62 (1): 2–18.

Hanna, S. and Rowley, J. (2011) Towards a strategic place brand-management model. Journal of Marketing Management 27 (5-6): 458–476.

Hatch, M.J. and Rubin, J. (2006) The hermeneutics of branding. The Journal of Brand Management 14 (1): 40–60.

Hatch, M.J. and Schultz, M. (2010) Toward a theory of brand co-creation with implications for brand governance. Journal of Brand Management 17 (8): 590–604.

Hauser, G. (1999) Vernacular Voices: The Rhetoric of Publics and Public Spheres. Columbia, SC: University of South Carolina Press.

Hauser, G. (1997) On publics and public spheres: A response to Phillips. Communication Monographs 64 (3): 275–279.

Ind, N. and Bjerke, R. (2007) The concept of participatory market orientation: An organisation-wide approach to enhancing brand equity. Journal of Brand Management 15 (2): 135–145.

Jensen, O.B. (2007) Cultural stories: Understanding cultural urban branding. Planning Theory 6 (3): 211–236.

Johnstone, B. and Baumgardt, D. (2004) ‘Pittsburghese’ online: Vernacular norming in conversation. American Speech 79 (2): 115–145.

Judkis, M. (2012) Portalandia, your 15 minutes are up. Long live Pittsburgh. The Washington Post, http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/arts-post/post/portlandia-your-15-minutes-are-up-long-live-pittsburgh/2012/01/03/gIQAMUlSYP_blog.html, accessed 14 August 2012.

Kavaratzis, M. (2005) Place branding: A review of trends and conceptual models. Marketing Review 5 (4): 329–342.

Kavaratzis, M. (2009) Cities and their brands: Lessons from corporate branding. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 5 (1): 26–37.

Kavaratzis, M. (2012) From ‘necessary evil’ to necessity: Stakeholders’ involvement in place branding. Journal of Place Management and Development 5 (1): 7–19.

Kavaratzis, M. and Ashworth, G. (2005) City branding: An effective assertion of identity or a transitory marketing trick? Tijdschrift Voor Economische en Sociale Geografie 96 (5): 506–514.

Kavaratzis, M. and Hatch, M.J. (2013) The dynamics of place brands: An identity-based approach to place branding theory. Marketing Theory 13 (1): 69–86.

King, C. and Crommelin, L. (2013) Surfing the yinzernet: Exploring the complexities of place branding in post-industrial Pittsburgh. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 9 (4): 264–278.

Klijn, E.H., Eshuis, J. and Braun, E. (2012) The influence of stakeholder involvement on the effectiveness of place branding. Public Management Review 14 (4): 499–519.

Kotler, P., Haider, D. and Rein, I. (1993) Marketing Places. New York: Free Press.

Laaksonen, P., Laaksonen, M., Borisov, P. and Halkoaho, J. (2006) Measuring image of a city: A qualitative approach with case example. Place Branding and Public Diplomacy 2 (3): 210–219.

Levy, F. (2010) America’s most livable cities. Forbes, http://www.forbes.com/2010/04/29/cities-livable-pittsburgh-lifestyle-real-estate-top-ten-jobs-crime-income.html, accessed 12 June 2012.

Northdecoder. (n.d.) ND tourism dept. fail: New ‘legendary’ ad campaign. NorthDecoder.com, http://www.northdecoder.com/Latest/nd-tourism-dept-fail-new-qlegendaryq-ad-campaign.html, accessed 7 November 2011.

O’Toole, C. (2011) I heart my city: Christine’s Pittsburgh. Intelligent Traveler. National Geographic.com.

Parehka, R. (2011) Buffalo’s new tagline highlights the worst of tourism marketing: Ad Age highlights some of America’s most atrocious slogans. Ad Age 19 May, http://adage.com/article/news/buffalo-s-tagline-highlights-worst-tourism-marketing/227555/, accessed 19 June 2013.

Paulsen, K.E. (2004) Making character concrete: Empirical strategies for studying place dimension. City and Community 3 (3): 243–262.

Peel, D. and Lloyd, G. (2008) New communicative challenges: Dundee, place branding and the reconstruction of a city. The Town Planning Review 79 (5): 507–532.

Pittsburgh Dad. (2011) Watching the steelers, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dgg60Kxn5SO, accessed 12 December 2011.

Rainisto, S.K. (2003) Success factors of place marketing: A study of place marketing practices in Northern Europe and the United States. Dissertation Helsinki University of Technology. Institute of Strategy and International Business, Esbo, Finland.

Richardson, T. and Jensen, O.B. (2003) Linking discourse and space: Towards a cultural sociology of space in analysing spatial policy discourses. Urban Studies 40 (1): 7–22.

Ricoeur, P. (1984) Time and Narrative. Vol. 1. Translated by K. Blamey and D. Pellauer Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Ricoeur, P. (1977) The Rule of Metaphor: The Creation of Meaning in Language. Toronto, Canada: University of Toronto Press.

The New Colonist. (n.d.) Sustainable city news: Pittsburgh. http://www.newcolonist.com/pittsburgh.html, accessed 12 May 2011.

Trueman, M.M., Cornelius, N. and Killingbeck-Widdup, A.J. (2007) Urban corridors and the lost city: Overcoming negative perceptions to reposition city brands. Journal of Brand Management 15 (2): 20–31.

Zenker, S. and Seigis, A. (2012) Respect and the city: The mediating role of respect in citizen participation. Journal of Place Management and Development 5 (1): 20–34.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Hudak, K. Dahntahn discourses and neighborhood narratives: Communicating the city brand of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Place Brand Public Dipl 11, 34–50 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1057/pb.2014.24

Received:

Revised:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/pb.2014.24