Abstract

Much research documents that middle-income households are facing high prevalence of economic insecurity associated with altruistic transfers to relatives in need. The focus of our examination is across and within generations of the same family tree that have grown up in different public policy regimes. Using panel data on U.S. families, we extend the breadth and depth of the work of Chiteji and Hamilton (2002). We find that, compared to their white counterparts, third-generation, middle-income Black families are disproportionately exposed to relatives who face poverty, unemployment, and wealth disparity. Additionally, we find that economic insecurity in the family tree is one of the largest contributors to the Black-White wealth gap.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

However, there is a potential flaw with the Chiteji and Hamilton (2002) specification. The inclusion of parental wealth and receipt of inheritance is likely simultaneously correlated with the wealth of their offspring.

Due to low sample sizes for families where the head has a college degree, we do not examine Black-White Oaxaca-Blinder decompositions for this group.

For an orientation on this approach, see Gujarati and Porter (2009).

Further evidence is provided by Hamilton, Darity, Price, Sridharan, and Tippett (2015, 5) using data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation. The authors find that even among Black-White households with equal levels of educational attainment, there are unequal levels of net wealth at the median. They also reveal that White households without a high school degree are in possession of higher levels of median wealth than Black households that are college-educated.

In context, this overall finding is similar to the finding by Chiteji and Hamilton (2002); they report that these factors explain 55%.

One would think that the collective attribute of sibling hardship, parental hardship, grandparental hardship, and cousin need would explain even more of the racial wealth gap. However, sample size limitations prevented us from computing the decomposition with sibling, parental, grandparental, and cousin hardship variables. The sample size reduces greatly, particularly with respect to cousins (see Appendix 12), as the extended kin network is added to the analysis.

The inverse hyperbolic sine log transformation takes the form of sinh^-1 = log(net wealth + (net wealth^2 + 1)^1/2).

Moreover, to better understand the role of contributors, we examine parts of the wealth distribution through quantile regressions (see Appendix 13).

As an alternative approach to the Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition, we present results for average treatment effects (ATE) of kin network economic insecurity on net wealth (see Appendix 13).

Daw et al. (2016) use the PSID data and find that one of the most dramatic decreases in the average number of kin can occur among cousins as they develop from early childhood to middle age. Why do cousin counts rapidly decrease with age? Findings by Daw et al. (2016) indicate that mortality may offer some explanatory power, which provides context for why we run into sample size limitations.

References

Altonji J, Doraszelski U (2005) The role of permanent income and demographics in black/white differences in wealth. J Human Res 40(1):1–30

An W, Glynn AN (2021) Treatment effect deviation as an alternative to Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition for studying social inequality. Sociol Methods Res 50(3):1006–1033

Aquinas T, Sigmund P (1988) St. Thomas Aquinas on politics and ethics. W.W. Norton, New York, NY

Avery RB, Rendall MS (1997) The contribution of inheritances to Black-White disparities in the United States. Cornell University Bronfenbrenner Life Course Center Working Paper 97-08, Ithaca

Begley J (2017) Legacies of Homeownership: housing wealth and bequests. J Hous Econ 35(March):37–50

Blau F, Graham J (1990) Black/White differences in wealth and asset composition. Quart J Econ 105(2):321–339

Brown T (2012) The intersection and accumulation of racial and gender inequality: Black women’s wealth trajectories. Rev Black Polit Econ 39(2):239–258

Brown T (2016) Diverging fortunes: racial/ethnic inequality in wealth trajectories in middle and late life. Race Soc Probl 8(1):29–41

Brown C, Corcoran M (1997) Sex-based differences in school content and the male-female wage gap. J Law Econ 15(3):431–465

Burbidge J, Robb AL (1985) Evidence on wealth-age profiles in Canadian cross-section data. Can J Econ 18(4):854–875

Burbidge J, Magee L, Robb AL (1988) Alternative transformation to handle values of the dependent variable. J Am Stat Assoc 83(401):123–127

Charles K, Hurst E (2003) Correlation of wealth across generations. J Polit Econ 3(6):1155–1182

Chiteji NS (2010) Wealth in the extended family: an American dilemma. Du Bois Rev 7(2):357–379

Chiteji NS, Hamilton D (2002) Family connections and the Black-White wealth gap among middle-class families. Rev Black Polit Econ 30(1):9–28

Chiteji NS, Hamilton D (2005) Family matters: kin networks and asset accumulation. In: Sherraden M (ed) inclusion in the American dream: assets, poverty, and public policy. Oxford University Press, New York, NY, pp 87–111

Compton R, Giedeman D, Muller L (2018) Racial differentials in the wealth effects of the financial crisis and Great Recession. J Econ Race Policy 1:126–141

Conley D (1999) Being Black, living in the red: race, wealth, and social policy in America. University of California Press, Berkeley, CA

Conley D, Glauber R (2008) Wealth mobility and volatility in Black and White. Center for American Progress, Washington, DC

De La Cruz-Viesca M, Chen Z, Ong PM, Hamilton D, Darity WA Jr (2016) The color of wealth in Los Angeles. Duke University, The New School, University of California, Los Angeles, Insight Center for Community Economic Development.

Darity WA Jr, Hamilton D, Stewart JB (2015) A Tour de Force in understanding intergroup inequality: an introduction to stratification economics. Rev Black Polit Econ 42(1–2):1–6

Davies JB, Fortin NM, Lemieux T (2017) Wealth inequality: theory, measurement and decomposition. Can J Econ 50(5):1224–1261

Daw J, Verdery AM, Margolis R (2016) Kin count(s): educational and racial differences in extended kinship in the United States. Popul Dev Rev 42(3):491–517

Dawson MC (2014) The hollow shell: Loic Wacquant’s vision of state, race and economics. Ethn Racial Stud 37(10):1767–1775

Dawson MC, Francis MM (2016) Black politics and the neoliberal racial order. Publ Cult 28(1):23–62

Federal Reserve Board (2016) Report on the economic well-being of U.S. households in 2015. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Washington, DC. Available at https://www.federalreserve.gov/2015-report-economic-well-being-us-households-201605.pdf

Federal Reserve Board (2019) Survey of household economics and decisionmaking (SHED) data set. Available at https://www.federalreserve.gov/consumerscommunities/shed_data.htm. (Accessed 5/1/2021)

Gale WG, Scholz JK (1994) Intergenerational transfers and the accumulation of wealth. J Econ Perspect 8(4):145–160

Gittleman M, Wolff E (2004) Racial differences in patterns of wealth accumulation. J Human Res 39(1):193–227

Gujarati D, Porter D (2009) Basic econometrics. McGraw-Hill Irwin, New York

Hamilton D, Darity WA Jr (2017) The political economy of education, financial literacy, and the racial wealth gap. Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, 99(1): 59–76.

Hamilton D, Darity WA Jr, Price A, Sridharan V, Tippett R (2015) Umbrellas don’t make it rain: why studying and working hard isn’t enough for Black Americans. Duke University Center for Social Equity. Available at https://socialequity.duke.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/Umbrellas_Dont_Make_It_Rain_Final.pdf

Heflin C, Pattillo M (2002) Kin effects on Black-White account and home ownership. Sociol Inq 72(2):220–239

Heflin C, Pattillo M (2006) Poverty in the family: race, siblings, and socioeconomic heterogeneity. Soc Sci Res 35(4):804–822

Kijakazi K, Atkins RM, Paul M, Price AE, Hamilton D, Darity WA Jr (2016) The color of wealth in the nation’s capital. Duke University, The New School, Insight Center for Community Economic Development, Urban institute

Kline P (2011) Oaxaca-Blinder as a reweighting estimator. Am Econ Rev Papers Proc 101(3):532–537

Kochlar R, Fry R (2014) Wealth inequality has widened along racial, ethnic lines since end of Great Recession. Pew Research Center, Washington, DC

Lusardi A, Schneider DJ, Tufano P (2011) Financially fragile households: evidence and implications. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Spring: 83–134.

McGonagle KA, Schoeni RF, Sastry N, Freedman VA (2012) The panel study of income dynamics: overview, recent innovations, and potential for life course research. Longitudinal Life Course Stud 3(2):268–284

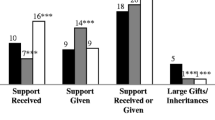

McKernan S, Ratcliffe C, Simms M, Zhang S (2014) Do racial disparities in private transfers help explain the racial wealth gap? New Evid Longitudinal Data. Demogr 51(3):949–974

Menchik PL, Jianakoplos NA (1997) Black-White wealth inequality: is inheritance the reason? Econ Inq 35(2):428–442

Meschede T, Darity WA Jr, Hamilton D (2015) Financial resources in kinship and social networks: flows and relationship to household wealth by race and ethnicity among Boston residents. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston Community Development Discussion Paper No. 2015-02. Available at https://www.bostonfed.org/publications/community-development-discussion-paper/2015/financial-resources-in-kinship-and-social-networks-flow-and-relationship-to-household-wealth-by-race-and-ethnicity-among-boston-residents.aspx

Munoz AP, Kim M, Chang M, Jackson RO, Hamilton D, Darity WA Jr (2015) The color of wealth in Boston. Duke University, and The New School. Available at https://socialequity.duke.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/The-Color-of-Wealth-in-Boston.pdf

Nam Y, Hamilton D, Darity WA Jr, Price AE (2015) Bootstraps are for Black kids: race, wealth and the impact of intergenerational transfers on adult outcomes. Oakland, CA: Insight Center for Community Economic Development.

Oliver M, Shapiro T (2006) Black wealth/White wealth. Routledge, New York, NY

Pfeffer FT, Danziger S, Schoeni RF (2013) Wealth disparities before and after the Great Recession. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci 650(1):98–123

Rauscher E (2016) Passing it on: parent-to-adult child financial transfers for school and socioeconomic attainment. RSF: Russell Sage Found J Soc Sci, 2(6): 172–196.

Robles B, Brewer R, Lui M, Leondas-Wright B, Adamson R (2006) The color of wealth: the story behind the U.S. racial wealth divide. The New Press, New York. Available at https://thenewpress.com/books/color-of-wealth

Shapiro TM (2004) The hidden cost of being African American: how wealth perpetuates inequality. Oxford Press, New York, NY

Shapiro T, Meschede T, Osoro S (2013) The roots of the widening racial wealth gap: explaining the Black-White economic divide. Brandeis University, Institute on Assets and Social Policy

Sherraden M (1991) Assets and the poor: a new American welfare policy. Vintage Books, New York, NY

Taylor P, Kochhar R, Fry R, Valasco G, Motel S (2011) Twenty-to-one: wealth gaps rise to record highs between Whites, Blacks and Hispanics. Pew Research Center, Washington, DC

Acknowledgements

We thank Ngina Chiteji, Samuel Myers Jr., Teresa Ghilarducci, William Darity Jr., Brandon Jordan, Ben Fried, James Kelly, anonymous referees, and seminar participants at the New School for Social Research, the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, 2016 Eastern Economic Association Annual Conference, 2021 Association for Public Policy Analysis and Management Fall Conference for helpful comments. Toney acknowledges that material of this paper was financially supported by the Elinor Goldmark Black Dissertation Fellowship for Advanced Studies in the Dynamics of Social Change (2016-2017 academic year).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendices

Appendix 1. Accounting for Observations Across Multiple Family Generations and Generational Peers

Table 12

Appendix 2. Definitions and Measures

Appendix 2.1. Using Various Definitions of “Middle Income”

There are various ways in which the middle-income group may be empirically defined. Chiteji and Hamilton (2005) offer three approaches: an income approach, defined in terms of the middle 60th percentile of the income distribution, an education approach, defined by individuals who hold a college degree with at least 16 years of education, and a labor occupation approach, defined as whether someone holds a position in the management or professional fields. We examine middle-income families since they are better off than their low-income peers, and thus are more capable of participating in the transfer of resources (Chiteji and Hamilton 2002).

Appendix 2.2. Measures of Variables for Empirical Analysis

Wealth, both with and without home equity, with the latter being a more liquid indicator of household financial well-being, is a core variable of this analysis. Wealth is defined as the sum of household debt subtracted from the sum of household assets, which include owning a farm or business, checking or savings accounts, real estate, stocks, vehicles, bonds, and individual retirement accounts. Home equity is defined as the value of the home subtracted by the amount of mortgage outstanding. Included as part of debt are liabilities, except loans from mortgages or vehicles. Examining wealth in the family tree allows one to see a more expansive view of financial resource or financial drain (un)available to a family and how that connects to race and social stratification. For example, Chiteji (2010) finds that grandparental wealth and college attainment of grandchildren are positively related.

Age of the head of household and age squared of the head of household. The impact of the first degree (i.e., age) is that, at some point, wealth accumulation tends to rise as adults in their prime years gain more experience through work. The impact of the second degree (i.e., age squared) is that wealth accumulation slows, or falls, as the adult ages, moves out of the labor market, and begins to dissave.

Number of children in the household. Wealth can be used to promote the well-being of children, and the presence of children can influence the amount of resources available.

Sex of the head of the household (this is cast as a dummy variable where 1 = female, 0 = otherwise). Social stratification and discrimination tend to be associated with lower wealth for households headed by females.

Marital status of the head of the household (this is coded as a categorical variable where 1 = married, 0 = otherwise). Married couples can benefit from pooling resources among themselves. Greater power to accumulate is analogous to family units experiencing economies of scale.

Years of education attained by the household head. Education is associated with greater wealth accumulation.

Average lifetime income (this variable is the mean of family income over the previous five working years, where data is taken from 2013, 2015, 2017, and 2019 waves of the PSID). Given the volatility of contemporary income and its simultaneity with assets and debts, we use the more robust 5-year average income that is de-trended from year-to-year fluctuations.

Race of the head of the household (where 1 = Black, 0 = otherwise). Scholarship shows that, on average, Black families are more likely to face wealth disparity compared to White families.

Professional or managerial status for head of household (a dummy variable indicating that individual works in a professional or managerial position as defined by the 2000 U.S. Census). The underlying principle of including managers and professionals is that jobs with higher status offer the ability to accumulate wealth.

Economic hardship in the family tree (categorical variable where 1 = receives Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF), or food stamps, or is facing unemployment, 0 = otherwise). Economic hardship measure is computed for adult siblings, parents, grandparents, and cousins. Chiteji and Hamilton (2002, 2005) reveal that hardship can contribute to Black-White wealth disparity among middle-income earners.

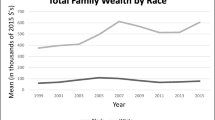

Parental wealth during childhood. Both this paper and Chiteji and Hamilton (2002) use the variable of parental wealth as a child in the decomposition. We compile data on all children ages 6–21 living in households with their parents in 1984 but who are then heads or wives in 2019. The “total family wealth” for a child in 1984 is reference to the family in which they are living, as they would not have contributed to this household wealth. Conley and Glauber (2008) also use this approach to explore the intergenerational transmission of financial wealth.

Access to inheritance. In the PSID, participants are surveyed on whether or not they accepted large gifts or inheritances of money or property worth $10,000 or more. This paper supports and maintains the assumption of McKernan et al. (2014) that the gateway for parental wealth to significantly impact their adult children’s wealth is through private transfers. Provided that parental wealth during childhood is a broad indicator of economic transfers, the variable inheritance is no longer needed in the decomposition technique.

Appendix 3. Methodology Used to Explore the Life Course of Cousins

We link the sibling map to the 1984–2019 PSID core family level files to explore cousins who are living with their parents in 1984 and are between the ages of 6 and 21 but who are then household heads in 2019. We match cousins by working from a sibling map in the Family Identification and Mapping System (intra-generational feature of FIMS mapping) that is not restricted to full siblings (same biological father and mother), so it also includes half-siblings.

Once we identify the sibling sample, we then look to their children (who would be the cousin pairs). The cousin sample (1404) in 1984 is identified by looking at the relationship to household head variable, where codes 30 and 33 are “son or daughter of head” or “stepson or stepdaughter of head,” respectively. Cousins who are then adults are identified by looking at the relationship to head variable, where codes 10, 20, and 22 are cousins as household head or wife of household head in 2019. The full sample size for adult cousins in the PSID data is 548.Footnote 10

To our knowledge, there are no studies that explore the life course of cousins in the context of extended family wealth. There are, however, studies that chronicle the wealth accumulation in the life course of older adults by race (Brown 2016) and by race and gender (Brown 2012). We complement previous life course scholarship by focusing on the wealth position of cousin pairs when they are living with their parents and when they are household heads.

Appendix 4. Supplementary Regression Models

Table 13

Appendix 4.1. Pooled OLS Regression Models

Appendix 4.2 Quantile Regressions

To further investigate the role of contributors, we use quantile regressions. We present decomposition results from the 10th percentile in Table 14 and the 90th percentile in Table 15. A common theme that arises from the two tables is that disparities in life cycle, demographic, socioeconomic, and family background variables explain very little of the racial wealth gap. When we adjust for socioeconomic status, we find that Black households and White households exhibit similar behavior (Conley 1999).

To explore the typical experience of a household, we use a quantile regression (median = 0.5) with dichotomous variables for economic insecurity in the extended family. In Table 16, we display the results from the median regression model. We find that there is a negative association between median household wealth and having a sibling or grandparent that is dealing with economic insecurity, which is consistent with our hypothesis.

Table 14

Table 15

Table 16

Appendix 4.3. Average Treatment Effects of Kin Network Economic Hardship on Net Wealth

Oaxaca-Blinder parameter estimates can be equivalent to causal counterfactual treatment effects. However, as An and Glynn (2021) note, this equivalence may not always hold. Estimating a binary treatment effect specification that is altered to vary on covariates of interest (race, income) is recommended to determine if the treatment effect changes.

In Table 17, we present results for average treatment effects (ATE) of kin network economic insecurity on net wealth. Raw net wealth for the middle-income group is the outcome-dependent variable. Meanwhile, grandparental hardship is the binary treatment variable. In the full model that matches on all covariates, the covariates include average lifetime income, parental wealth, age, age squared, educational attainment, children in the household, marital status, managerial or professional occupational status, sex, race, sibling need, and parental need. When there are no omissions of covariates of interest (i.e., full model), the average net wealth for respondents with grandparental hardship is $57,589 less than the average net wealth for respondents without grandparental hardship. We then find that the treatment effect varies with the omissions of covariates of interest (e.g., race, educational attainment, average lifetime income, parental wealth, managerial or professional occupational status, sibling need, parental need). Such a result is suggestive of a causal effect and reinforces the findings from the Oaxaca-Blinder decomposition.

In addition, as both Oaxaca-Blinder and treatment effect estimators are generalized weighting estimators (Kline 2011; Davies et al. 2017), if both methods produce similar results, this can make a case for robustness. Indeed, we find that neglecting to account for variation in average lifetime income can result in an average treatment effect estimator that is biased upward by 30.4%. Meanwhile, neglecting to account for difference in parental wealth can result in an average treatment effect that is biased downward by 9.47%. In contrast, neglecting to adjust for the variation in sibling need and parental need may result in an estimator that is biased downward by 45.06% and 14.39%, respectively. Significantly, results from both ATE and Oaxaca-Blinder methods recognize that kin network economic hardship, parental wealth, and average lifetime income are dominant contributors to differences in net wealth.

Table 17

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Toney, J., Hamilton, D. Economic insecurity in the family tree and the racial wealth gap. Rev Evol Polit Econ 3, 539–574 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43253-022-00076-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43253-022-00076-5