Abstract

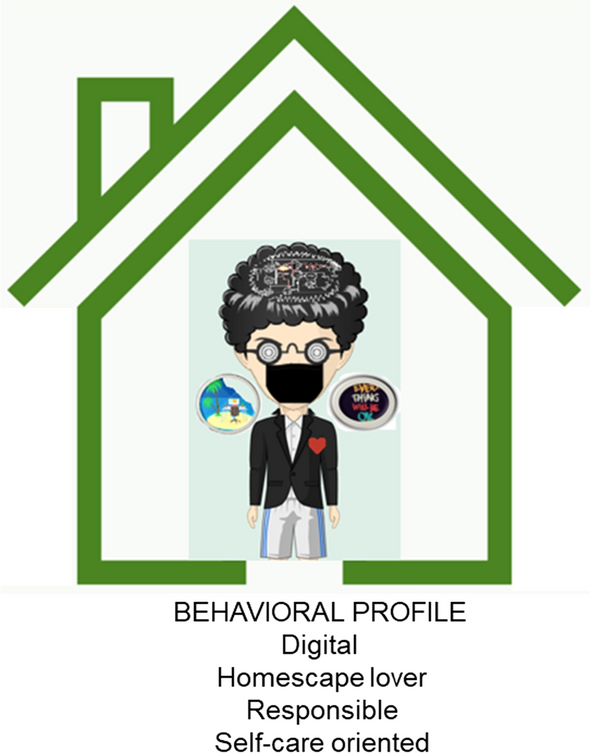

The changes in consumption habits brought about from the covid-19 pandemic is completely reshaping the consumer profiles examined by different organizations. The purpose of this paper is to contribute to the consumer behavior studies by analyzing changes post-disasters. Our paper aims at understanding Italians’ lifestyle and behaviours during and post crisis in order to explore what behaviours people would keep after the disaster and to identify possible megatrends. Through a mixed method approach, we propose a trendy avatar which summarizes in its representation the four categories emerged from our explorative study: (1) digital, (2) homescape lovers, (3) responsible and (4) self-care oriented. Drawing on the new behavioural consumer profile proposed, some research avenues and managerial implications are advanced.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has emerged as a global catastrophe by affecting every feature of our lives. While the capacity to provide forecasting is restricted, it seems likely that the impact of COVID-19 is bound to be abrupt and profound in relation to marketing strategies and principles (Hoekstra & Leeflang, 2020). The wide-ranging upheaval of the COVID-19 outbreak is reconfiguring the discipline of marketing in a variety of directions. Notwithstanding the human catastrophe of the sudden rise in deaths and dramatic social effects the pandemic-driven lockdown might represent an opportunity to study the singular and unprecedented changes in consumer behavior (Sheth, 2020).

Right from the beginning of the pandemic, a large number of empirical studies have been published, for instance the study by Naeem (2020) has argued that during the COVID-19 pandemic the use of social media has affected customer psychology by improving its capacity to take optimal consumption decisions. In the same vein, the study by Mason et al. (2020) analyzes the alteration of consumer needs in the USA during the lockdown. The authors illustrated that the changes have affected both purchasing behavior and post-purchase satisfaction.

Unfortunately, the changes in marketing habits and procedures were provoked by such a very rare and unpredictable event as a COVID-19 pandemic. Therefore, the traditional marketing frameworks, much more focused on the symbolic value of products and hedonistic consumption experiences, seem to partially support the analysis by failing to capture some external determinants (Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982; Kim et al., 2019). To address this absence and align the actor-based marketing analysis to such an enormous and tragic external event as the COVID-19 pandemic, we have drawn from another block of managerial literature that is focused on coping with crisis, catastrophe, and disaster. In fact, disaster management is able to provide some frameworks and lenses for analysis to reveal the effects of huge, rare, and unpredictable negative events. Accordingly, the COVID-19 outbreak acts as a Black Swan (Taleb, 2007) and it cannot be studied using ordinary theoretical approaches. Therefore, we decided to examine disaster management to conceptualize the main crisis drivers (Taleb et al., 2009). Disaster management studies (Grossi, 2005; Park et al., 2015; Pearson & Clair, 1998; Taleb et al., 2009) suggest analyzing the consequences of a catastrophe, adopting an event timeline, and splitting a disaster into phases. From the very beginning, marketing scholars have addressed the topic of behavioral changes in consumption habits, although what seems to be lacking is a deep understanding of the correlation between behavioral consumption frameworks and disaster management determinants. Our study tries to exploit the stage of the catastrophe recovery scheme, drawing from the disaster management field to investigate the real changes in consumption habits. Indeed, our work seeks to pursue three objectives: first, investigating consumer lifestyle changes due to the lockdown; next, looking further into the behaviors that people are willing to make permanent; and last, profiling a new consumer behavioral pattern. Specifically, disaster studies provide a mitigation measure scheme that inspired our quantitative investigation. Indeed, scholars approached a negative event by listing several mitigating measures that, during the outbreak, in Italy just as all around the world, corresponded to social distancing and compulsory home life. At the same time, the literature on the crisis argues that the reaction of people and a recovery phase always follows that of mitigation. As part of the reaction phase, people started to change their habits and also consumer behavior, with some of the factors related to the mitigation phase affecting consumption paradigms and leading toward simpler lifestyles and to the utilitarian value of goods (Cozzolino, 2012). Such a kind of change might be understood as part of the reaction or recovery phase in terms of consumer attitudes and resilience. Accordingly, we harness such a chronological perspective with the aim of studying if people will keep the consumption changes after the lockdown and, consequently, if a new consumer behavioral profile will emerge. In other words, this study aims to identify various consumer response attitudes. Thus, the research question is: how does COVID-19 change consumers' lifestyle and behaviors and what habits will remain post-crisis?

To answer to this research question we chose the Italian situation, because Italy was one of the countries most affected by the pandemic; indeed, the official news was posted on the Italian Ministry of Health website on March 10, the decree stating a limitation of movement for Italian citizens to mitigate the outbreak of the virus. Such restrictions were without precedent in Italy. Meanwhile, due to the extraordinary impact on social life and peoples’ habits; citizens were obliged to respect social distancing measures; we decided to begin this article during the first phase of lockdown in Italy. We immediately thought about analyzing the disaster impact from a marketing perspective. We were witnessing a huge catastrophe that would provoke a disruptive transformation in social life. At the same time, consumer behavior was changing, so we started to gather data to capture the new direction of customer changes.

The phase of data analysis is based on a mixed method approach (Dunning et al., 2008) organized in two phases (quantitative and qualitative). In order to achieve a deep understanding, we set up a semi-structured questionnaire. We investigated the adaptation of consumers to new lifestyle habits by structuring the questions to achieve a full understanding of what the new consumption habits that the respondent has adopted are, and which of them the respondent perceives to be permanent, even after the lockdown. To expand comprehension of the phenomenon and for the sake of clarity, we arranged a qualitative phase of analysis by interviewing ten respondents belonging to the incumbent sample. This approach permits us have a deep insight into consumer changes and its latent categories of new habits that are strictly related to pandemic measures.

To accomplish our research project this paper is shaped as follows. In the first part we explain the theoretical background that supports our empirical work. Specifically, the first subsection concerns the exploration of the fundamentals of disaster management. The second part of the theoretical background section shows the crucial paradigm on consumer behavior and its evolution during the COVID-19 outbreak. The second section is dedicated to illustrating the methodology. Due to its mixed approach this creates both qualitative and quantitative investigations. The section relating to the findings, which replaces the methodical analysis pattern, illustrates both the qualitative and quantitative parts. At the end we debate our discussions and provide implications for scholars, practitioners, and policy makers

2 Literature background

2.1 Disaster management: a lens of analysis for revealing new behavioral profiles

Disaster management has a huge body of parallel fields of study that can sufficiently provide a consistent clarification on the main characteristics of the disaster management concept. Therefore, the literature has addressed the theme of negative, relevant, and unexpected events labelling the studies in different ways. As a consequence, catastrophe management, emergency management, crisis management, and Black Swan management are the strains of literature that contribute to powering the understanding of the study of disaster management (Grossi, 2005; Park et al., 2015; Pearson & Clair, 1998; Taleb et al., 2009). The fragmentation of the study about disaster management is not just a matter of semantic clarification; instead it is related to several facets of disaster events. In fact, a large realm of disaster definitions exists (Perry, 2007); this study exploits the definition of McFarlane and Norris (2006, p. 4). The authors have argued that disasters are “potentially traumatic events that are collectively experienced, have an acute onset, and are time-delimited”. A pioneer of crisis management like Burnett (1998) described seven categories of changes during a catastrophe at business level: (1) heroes are born; (2) changes are accelerated; (3) latent problems are faced; (4) people can be changed; (5) new strategies evolve; (6) early warning systems develop; and (7) new competitive edges appear (Burnett, 1998). The outbreak is depicted by exploiting the study of Taleb (2007) as a Black Swan event. Accordingly, the COVID-19 pandemic has the main features of a Black Swan in that it has an unconstrained impact, with no room for forecasting. The study of Neal and Philipps (1995) argues that disaster events open the route to new collective behaviour. The study has been useful for unpacking the disaster response. It was even full of novelty in considering the focal role of a group or subgroup of people in moving as a crowd. Disaster management has taken into account the timeline of a tragic event, especially for assessing the impact and confronting it. Houston (2012) has divided the disaster into phases by splitting it into: a pre-event phase that is hard to predict, an event phase that concerns the disaster spread, and a post-event phase that corresponds to the negative impact of the event. Cozzolino (2012) has presented an interesting approach on the evolution of a disaster and its correlation with the recovery path. The author has analyzed catastrophic events by introducing the concept of a disaster management cycle (Marshall & Schrank, 2014). The author argues that disaster management is framed as a cycle and that it is essentially formed by four categories: mitigation, preparedness, response, and recovery.

The theoretical framework that supports our study is inspired most of all by Cozzolino’s (2012) study. Indeed, we adopt the disaster recovery path to investigate the changes in consumer behaviors. Our work exploits the disaster management cycle of Cozzolino (2012) to understand the evolution triggered by the COVID-19 outbreak. Furthermore, Huston's (2012) study argues that a disaster is characterized by a post event phase that impacts on habits and behaviors. Our theoretical framework takes this post-event phase into account to discover customers' behavioral changes that might become permanent. To the best of our knowledge there are no extant studies that try to bridge disaster management and customer behavior. The work of Burnett is not directly focused on customer behavior, it addresses the changes in organization when a disaster occurs. As suggested by Burnett, there are no systematic or widely accepted strategies for managing crises (Burnett, 1998). Each disaster concurs with the loss of traditional business guidelines; therefore, it is needed to establish steps to limit negative impacts on markets. Highlighting this kind of consequence of disaster has been a crucial element in anticipating the emergence of spontaneous behavioral norms. Guion and his co-authors (2007) have faced the issue of behavioral changes of people, but only during the disaster. The authors argue that a catastrophe has the capacity to profoundly modify behavior (Guion et al., 2007). As a consequence of the negative event, people adopt a new lifestyle to directly or indirectly overcome the emergence of the disaster.

2.2 Italians’ lifestyle and behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic

In times of crisis, firms need to pay attention to consumer behaviors, reactions, and adaptation (Eger et al., 2021). The unexpected restrictions imposed during the COVID-19 outbreak (in early 2020), have made consumers deviate significantly from their usual shopping behavior (Eger et al., 2021). The more limited accessibility of store premises, the increase in digital shopping, the growth of self and home care orientation, and some other new habits, are reshaping the consumption paradigms (Eger et al., 2021). The need to investigate recent trends is crucial and useful to design new value propositions and consumer experiences (Dalli, 2004; East et al., 2016).

Postmodern consumption paradigms have long been characterized by demanding consumers oriented to the symbolic value of goods and services and hedonistic consumption experiences (Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982; Kim et al., 2019). After the COVID-19 crisis, some effects such as lockdown, social distancing, the shortage of available resources, home life, more time available, and the fear of contagion, have brought people back to simpler lifestyles and to the utilitarian value of goods (Sheth, 2020), such as buying food and basic goods, going out to the grocer’s, and using technology to feel close to loved ones.

New normal life derived from the consequence of the COVID-19 pandemic has pointed out the importance of time, space, and relations (Ferraresi, 2020), while increased digital adoption changed mobility patterns, changed purchasing behavior, increased awareness of health, and changed interpersonal behavior (SwisseRE institute, 2020).

With particular reference to purchasing and consumption behavior, before the COVID-19 pandemic, Italian consumers could mainly be identified as traditional shoppers, and only to a minor degree as online shoppers (called switch) (Zhai et al., 2017; Eger et al., 2021). Traditional shoppers and online shoppers use a single channel to shop, meanwhile switch shoppers are shoppers who buy online but have previously explored the store in the pre-purchase stage. If, previously, these shopping behaviors depended on many reasons, such as: type of products to buy, motivation (task or leisure), age, culture, the exogenous event of the pandemic and its restrictions have totally removed these paradigms by changing lifestyles and behaviors and shaping new habits and new consumption models toward a massive use of digitalization, a healthy lifestyle, and a local shopping orientation (Eger et al., 2021).

On this point, some recent studies have investigated the possible impact on individual habits and social consumption trends after the pandemic. For example, Sheth (2020) has analyzed the immediate impact derived from the general lockdown on consumer behavior with eight elements: 1. Hoarding, 2. Improvisation, 3. Pent-up demand, 4. Embracing digital technology (e.g. online meetings, digital education), 5. Shops come to the home, 6. Blurring of work-life boundaries, 7. Reunions with friends and family and 8. Discovery of talent. In the same vein, Hoekstra and Leeflang (2020) discussed the impact of the pandemic on consumer behavioral changes and five possible new marketing megatrends. In particular, the authors observed that digital technology should be used to enhance the connection between consumers and firms in a more emotional way (Connected Consumers); shopping habits have been characterized by the use of digital platforms and the consumption of local goods (shopping reinvented); moreover, authors have observed a propensity to protect health and lifestyle as new priorities for consumers (Healthy Living). An additional megatrend derived from an observation of the economic consequences of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the particular condition of middle and lower economic classes, who are keen to maintain their economic position and lifestyles (Middle Class and Lower Class Retreat). Finally, the authors observe a possible depopulation of large cities, where green areas are likely to become saturated soon, as well as a switch of market frontiers due to the impact of COVID-19 measures (e.g. the conversion of tourist services into agriculture) (Shifting Market Frontiers).

Against this backdrop, an interesting analysis may be carried out at a country level in the Italian context. Italy is well known all over the world for its food, art, fashion, and the Italian lifestyle, characterized by healthy consumption of food, healthy physical activity, and healthy prevention (Nomisma, 2020). Especially in some northern regions, this lifestyle was marked by fast work rhythms, well-defined roles within the family, and a lot of social activity (Nomisma, 2020). Italy was one of the countries most affected by the pandemic with over two million cases and over one hundred thousand dead (OMS, 2021). With the strict restrictions imposed by the Government, the COVID-19 pandemic has suddenly slowed down this lifestyle. On the one hand, it forced many cancellations (e.g. going to the restaurant, going to the gym, travelling), returning the country to the consumption of the 1980s. On the other hand, there was a speeding up of the dynamics of technological innovation, such as smart working, e-grocery, distance learning, and all public services, which were suddenly digitized (Deloitte, 2020). Furthermore, the need to stay at home has created a kind of comfort zone where Italians took refuge, especially to cook, unlike in previous years where there was almost an escape from the stove (Coop2020 Report). Thanks to the availability of time, the search for healthy food, and the need to reduce the family budget, people were made more aware and responsible, not only by cooking everything at home but also by purchasing from local suppliers (Cancello et al., 2020).

According to recent data (Nomisma, 2020), these trends also seem to have been confirmed in the months following the lockdown, in the so-called new normality, where people have shown a maintenance of respect for the hygiene and health regulations imposed by the pandemic, continuing to buy online and preferring sustainable products.

While the majority of the recent literature on consumer behavioral changes in Italy after the lockdown has been focused on food habits, this research aims to explore how the restrictions imposed by COVID-19 may influence long-term behavioral intentions, becoming new consumer trends. The present study contributes to the debate on behavioral changes and new trends of consumption and offers interesting insights for managers and policymakers.

3 Methodology

The purpose of this research is threefold. First, it analyzes the consumer lifestyle during the COVID-19 lockdown; second, it explores the behaviors that people would keep after the lockdown, and finally, it proposes to define the new consumer behavioral profile. Therefore, this study adopted a mixed-method approach (Dunning et al., 2008).

To achieve the research aims, we adopted an exploratory sequential strategy, first starting with a quantitative analysis and then using a qualitative assessment to gain more insights into the individuals’ perspectives toward identifying themselves under the categories revealed by the results of the quantitative study (Mikalef et al., 2019). More specifically, our research efforts comprise two phases. In phase 1, motivated by the aim of research, we used quantitative methods (explorative survey) and then, with the aim of analyzing if something changed five months after the end of the lockdown, in phase 2 we developed a qualitative analysis (short discussions) on previous respondents who have previously filled in the online survey in the first stage of the study (Mehta et al., 2020; Tashakkori & Creswell, 2007). This study was conducted in Italy because Italy was one of the countries most affected by the pandemic with 4,449,606 confirmed cases and 128,510 dead (OMS, August 2021). With the closure of all work activities (except for the primary goods supply chain), the forced transition to the use of digital technology to work and study, and the duty to stay at home, lifestyles have been profoundly reconfigured (Sheth, 2020).

3.1 Quantitative study

To examine the behavioral profile and lifestyles during the lockdown, a survey-based instrument was conducted on an Italian sample of people (n = 810) through a semi-structured questionnaire administrated via digital tools. The questionnaire was divided in five sections. Closed and open questions were included in the questionnaire. Given that the study was carried out during the COVID-19 pandemic, it did not precisely follow pre-existing measurement scales. Therefore, the mixed method study adopted is based on the sequential in-depth qualitative phase after the quantitative survey, which helps to confirm the results which emerged from the explorative study or reveals if something changed in the first section of the questionnaire related to the behavioral profile of the respondents during the lockdown. Individuals were asked to indicate their level of adjustment with each of the items related to ten questions (see Table 1) about opinions and adaptation to the COVID-19 conditions, using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (for nothing) to 5 (totally). To explore the behavioral intentions, people were invited to answer the following questions: “Are there any consumption habits that you will keep in the future after the pandemic crisis?” and “If yes, could you tell us what they are?”.

Data resulting from this open question were analyzed adapting the thematic analysis approach by Braun and Clarke (2006), where each author searched for meanings and patterns using an iterative and hermeneutical approach.

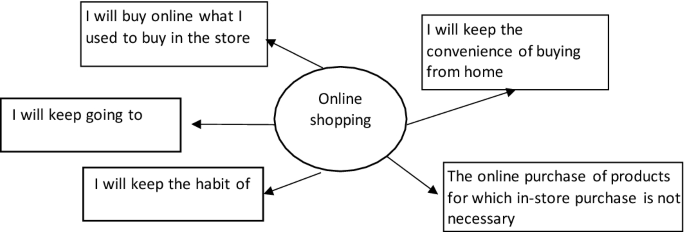

Thematic analysis is defined as “a method for identifying, analyzing, and reporting patterns or themes within the data” (Braun & Clarke, 2006, p.79). Through this process, initial codes were produced from a frequency analysis. Then, based on an inductive-deductive approach to the thematic analysis, we have manually identified some codes as an expression of the ideas or feelings given in the text (e.g. “I will keep going to shop online” has been coded into “online shopping”; “I want to save money and shop once a week for food” has been coded into “weekly planning of food shopping”) which were organized into broader categories (themes). Afterwards, the categories were re-examined and checked against the codes and the original data. Then we manually look at the codes we have created, identify patterns among them, and start to come up with themes. With the aim to identify behavioral factors, several codes were combined into a single theme to highlight the essential meaning (see Table 2 and the Fig. 1).

As national lockdown in Italy lasted from 9th of March to 18th of May, to be sure of capturing feelings derived from a new lifestyle, our questionnaire was disseminated in May 2020, almost at the end of the two month lockdown. Non-probability snowball sampling was used for the online survey due to the lack of an appropriate sampling frame (Nguyen et al., 2020). The questionnaire was disseminated via email to different groups of people (different age and work groups and residing across different areas in Italy) to prevent the formation of a homogeneous sample (Del Chiappa et al., 2021). People were invited to fill in the Google form and requested to find additional respondents. After a week of dissemination, a total of 810 surveys were returned.

3.2 Qualitative study

Second, a qualitative approach was followed (Hesse-Biber & Leavy, 2010) by using short discussions. Since the primary purpose of qualitative studies is to acquire relatively more comprehensive, updated knowledge on a specific topic, a short discussion is a convenient method to match such purposes (Lamont & White, 2005). Due to the exceptionality of the event, we adopted a qualitative approach after the explorative survey to verify if something had changed five months after the end of lockdown.

Hence, ten random short discussions were conducted in October 2020 with previous respondents who had previously filled in the online survey in the first stage of the study.

The focus of the discussions was to gain more insights into the individuals’ perspectives toward identifying themselves under the latent categories revealed by the results of the quantitative study. Respondents received an introduction to the purpose of the study and an explanation of the four latent categories of new habits. The following are examples of questions asked during the discussion: “how do you feel after two months of lockdown?” “how much have you adapted yourself to the new lifestyle required by the pandemic?”, “Are there any consumption habits that you will keep in the future after the pandemic crisis?” and “If yes, could you tell us what they are?” It was noticed that after the 7th discussion, the quality and quantity of information gained was almost repeated and no more ideas about the new lifestyle trends after COVID-19 were evolving, which is a signal of “data saturation” (Guest et al., 2006). To make sure that the data obtained was sufficient for the current study, three more discussions were added. Each discussion lasted between 15 and 22 min. A code containing letters to denote the first letter of the participant's name followed by a number (the age of the participant), and M/F to indicate their gender is assigned to each quote in the transcript to protect the anonymity of the participants. Transcripts were analyzed by using the coding process of dividing data into codes and themes related to the segments (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Interpretation of data collected helped in informing and further explaining the study results.

4 Findings

4.1 Quantitative findings

The socio-demographic profile of the sample is presented in Table 2. The majority of the interviewees were female (63.2%). In terms of age, 58 per cent were between 21 and 30, 17 per cent were between 31 and 40, 15 per cent above 41, and 10 per cent were below 20. The majority of the sample were from southern Italy (59.4%), 26.5 per cent from northern Italy, and 14.1 per cent from central Italy. In terms of employment status, a large portion of the sample (46.7%) were students, while the rest of the sample was divided among employed (26.7%), workers (6.9%), self-employed (7.5%), entrepreneurs (1.9%), and unemployed (10.5%).

With the aim of verifying how much the lifestyle and habits of the Italians have changed during the lockdown, participants were asked if and how much their eating, study, and work habits have changed and how much they adapted themselves to these new dynamics of daily life (see Table 3). Before proceeding with the questions illustrated in the tables, respondents were asked if they had the opportunity to continue their work from home (70%).

Despite this extraordinary and forced change, respondents showed a satisfactory level of adjustment. Moreover, people also asserted that some of the new habits (e.g. home working, home studying) should be implemented even after the pandemic emergency. On the other hand, concerning leisure activities (e.g. eating out vs home delivery), people showed a propensity to go back to eating out in the post-COVID stage. In addition, regarding shopping behavior, people showed a change in their approach to shopping. However, during the lockdown, they felt they were not much influenced by advertising. Overall, in response to the last question, people showed a high propensity to return to pre-COVID life, even if they have appreciated some changes.

To understand the appreciated habits that people would keep after the pandemic, respondents were asked “Are there any habits you will keep in your post-COVID stage?” 65 per cent responded positively.

In a first step analysis, in order to obtain quick feedback from the question, a frequency analysis was performed. It revealed two relevant habits that people would keep in their new lifestyle: online shopping and home cooking. In addition, the table illustrated some interesting insights, with similar frequencies. To move from the list format to something that provides a better basis for the identification of new behavioral trends of information, in a second step we applied the identify-categories strategy (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Vaughn & Turner, 2016), which is discussed in the next paragraph.

4.2 Qualitative findings

After having verified similar topics in the manifest responses, we developed coding that makes connections between similar themes. Thus, we tried to combine the manifest definitions with similar meanings, similar values, similar goals and similar tools into themes. Four themes have been identified which help to shape the new profile of Italian consumers after the COVID-19 lockdown.

The first category is digital resulting from the unified items “online shopping” and “digital meetings”; the second category has been called homescape lovers, which is the manifestation of all the home-related items (home cooking, home delivery, food delivery, home working, spending more time at home); the third category has been named responsible to group all the items related to a more conscious behavior (saving money, doing proximity shopping, avoiding waste, more reasoned purchases, weekly planning of food shopping). Finally, the fourth category has been labelled as self-care oriented to indicate the items related to personal care (wearing a face mask, social distancing, personal and home care, eating healthy food, physical activities, and time for hobbies).

The data collected from the discussions revealed that all the participants interviewed in the second stage identified themselves in the four categories. In particular, regarding the category ‘digital’, a participant indicated “During the lockdown I appreciated the time spent at home, despite the new reorganization of work, spaces and family” and “Even though my work has partially returned, I continue to spend a lot of time at home through digital tools” (Y54, F). Another participant indicated “I see myself in the habits indicated and for the future I’m trying to maintain a more balanced work-life lifestyle, take better care of myself and the environment for a better society” (M55, M). On this point, another participant found himself in the categories responsible behavior and homescape lover and said “I would definitely keep the habit of buying more stocks of basic goods and continue cooking at home, because I like it and it is certainly more hygienic and safe”.

Two participants declared that they had completely changed their lifestyle and that the time spent at home also changed their consumption behavior, especially in terms of values. Accordingly, one participant said “I saved money and I am currently not interested in buying non-primary goods” (G43, F). In addition, when we asked what changes you would bring with you in your post-COVID life, some of the participants declared “Home life made me think about life priorities: caring for myself, the environment, and loved ones” (M67, M). Additionally, an interesting comment came from a young participant who said “Despite the fact that COVID robbed me of the pleasure of seeing my friends and colleagues, I appreciated the utility of following lessons from home and I would like this possibility to always remain after this” (H65, M).

Overall, discussions confirmed the categories that emerged from the coding by confirming that the main behaviors that people would like to maintain even beyond the pandemic emergency are related to a more responsible behavior, oriented toward taking care of oneself and others, especially the environment, and a new awareness of the use of technology and home spaces.

5 Discussion and conclusion

COVID-19 has revealed the unstable foundations upon which much of what we take for granted in the developed world is built, from the complex nature of globalized manufacturing chains and infrastructures to just-in-time supermarket deliveries, as well as stark contrasts between public health systems or those financed by private insurance. Furthermore, the results attested that this pandemic has produced many changes in the lifestyles of the individual and of society as a whole. Lockdown created resilience and improvisation behaviors, which influenced behavioral intentions in a post-crisis stage.

We derived a new behavioral consumer profile by presenting a trendy avatar (see Fig. 1) which summarizes in its representation the four categories that emerged from our explorative study: (1) digital, (2) homescape lovers, (3) responsible and (4) self-care oriented (Fig. 2).

The avatar summarized the main evidence, which helped us to shape and propose the new profile of Italian consumers to manage the disaster after the COVID-19 lockdown. Indeed, the results presented in the previous Tables 2 and 3 attest to the fact that consumption behaviors in the next few years will not only be related to well-known and consolidated trends, such as the growing attention to health and wellbeing and the greater connection and sharing of information through digital devices, but also new orientations that will change the styles of living and consumer shopping globally.

In particular, the results of Table 2 show customers switching habits in favour of online shopping and adopting the principle of proximity when in need of a “brick and mortar store”. Another piece of evidence referred to the rise in awareness about wellbeing and personal care (e.g. wearing a mask), and also that there is an increase in interest in environmental issues and new ideas of living together. For these reasons, the new behavioral consumer profile shows the adoption of more responsible consumption behavior, for instance waste reduction, frugality, and the remodulation of the shopping budget and homemade cooking. Furthermore, one of the main drivers toward these personal and family changes has been the activation of smart working for many workers, and for others, the temporary suspension of work as a result of the closure of businesses and workplaces (for example, shops and restaurants). Thus, the concept of the house is being expanded by adding the perspective of a workplace i.e. home working, and reinforcing the idea of the pivotal place of families.

As illustrated above in Table 3, the respondents described that the lockdown period allowed exploration of hobbies and interests (e.g. home cooking) that we may never have had before. Many consumers want to keep these behaviors after the lockdown, are spending much more time cooking, and are paying more attention to food. Even if physically distant, digital technologies and social media have allowed us to enter the homes of others and to connect with them (Tables 4 and 5).

The knock-on effect of these behavioral changes can be the decline in the value of properties in large cities and the increase in the number of people who decide to move outside the metropolis, to the suburbs or to rural areas: a reversal of the trend compared to the beginning of the industrial revolution.

The economic impact was terrible, the effort and measures to neutralize the outbreak had a negative impact on different sectors. It occurred without any scope for predictions and it found the world completely unprepared to control and manage the outbreak and its consequences. As our very lives, companies, communities, and countries have been disrupted by this dramatic event, so too will be the philosophies, ideologies, and fundamental principles that theorize management studies, and more specifically the marketing field.

Furthermore, our results offer an interesting focus on utilitarian value (Overby & Lee, 2006; Li et al., 2018) as a need after the emergency period, contrary to the pre-COVID stage where consumers were more demanding and hedonistic in their consumption experience. For these reasons, grabbing and developing new paradigms (e.g. new lifestyle habits) to understand the impact of disasters on customer habits is relevant for the advancement of marketing studies because the situation we are likely to see continue after the pandemic will be that of many employees who continue to work from home.

Indeed, our research has shown that such a system worked during the lockdown, and this evidence will force many executives to no longer appeal to traditional arguments against requests for permission to work from home. This condition could in turn lead to a change in the expectations and culture of the workplace, where employees are evaluated based on their achievement in terms of the effectiveness and efficiency of the objectives assigned to them, and not on how many hours they sit behind their desk in the office. For these reasons, people who could continue to benefit from the extra time they have at home will be those whose working lifestyle has changed irreversibly. This situation is likely to favor employees over service industry workers, which means that not everyone will benefit equally from these changes in the future. Despite being enormously disruptive and painful, crisis management invariably also fuels the emergence of more reasoned purchases and proximity shopping by creating a more responsible profile. The difficulty in finding simple consumer products, or the inability to go shopping in stores, or perhaps just the fact that many of us had more time available, have developed online shopping skills by exploiting food delivery and resourcefulness in avoiding waste that have been largely shared online. Social media has opened small windows to share and compare with others regarding the different reaction mechanisms to the crisis through digital meetings. For these reasons, these conceptual limits related to these complex situations within disaster management have led to different lifestyles and behaviors. Other respondents have even affirmed the habit of dedicating themselves to physical activity around the house, or simply personal and home care in a small space on the windowsill of an urban window.

6 Implications

We used the COVID disaster event in order to see what is happening to consumer behavior during and after the event, especially regarding consumer behavior and lifestyle changes post-crisis. To answer this question, the study examined the Italian context to explore how Italians have already begun to make changes in their daily lives that allow the definition of a new consumer behavioral profile.

Our theoretical contribution refers to the consumer behavior literature (Mason et al., 2020; Naeem et al., 2020; Shet, 2020; Eger et al., 2021) by offering some megatrends that may affect future marketing trajectories. Indeed, the results provide a new behavioral profile based on four categories, which could be interesting insights for future research. Second, our study seeks to exploit the disaster management perspective (Grossi, 2005; Park et al., 2015; Pearson & Clair, 1998; Taleb et al., 2009) in order to understand what post-crisis changes in consumers' lifestyle and behavior (Shet, 2020; Eger et al., 2021) will have a definitive impact and what will not persist for a long time.

We attempt to develop some interesting implications for scholars and practitioners through this proposal of a new behavioral consumer profile.

Starting from the observation of the effects of the pandemic as a disastrous event on health, economy, and society, we analyzed the changes in the lifestyle and behavior of Italians, strongly affected by the pandemic, with the final purpose to identify possible future trajectories in purchase and consumption models. The four categories identify trends that were unimaginable until a year ago and which instead are characterizing these months, and perhaps they will enter into future behaviors, at least for a while, effectively reconfiguring the transaction models of sales, communication, etc.

Referring to the managerial implications, firms can consider the deployment of new business models to face the rise in online purchasing and behavioral consumer changes, which affect the logistics chain. On the other hand, the reconfiguration of the customer timeframe is changing from daily purchasing to weekly planning. This is because daily habits are changing in favor of the pleasure of cooking for oneself, which has been rediscovered, avoiding take-away dinners when returning from the office, carefully choosing a recipe, chopping and mixing ingredients, enjoying, in short, the process of preparing a meal. For these reasons, large scale distribution should take account of this significant evolution by updating its discount plan. Finally, organizations have to rethink their product and services proposals by considering the redesign of homespace as a new opportunity. Indeed, the respondents affirmed that they have been involved in a large number of creative projects during the lockdown at home with their family. Additionally, personal care organizations such as beauty companies have to consider that many Italians have rediscovered activities and habits that were lost due to a hectic modern life: making things exclusively for themselves and realizing how deeply satisfying and fulfilling this can be.

Referring to the theoretical implications, scholars interested in consumer behavior studies and disaster management literature (Grossi, 2005; Park et al., 2015; Pearson & Clair, 1998; Taleb et al., 2009) can exploit this research by considering the lens of this study on Italian consumers during the COVID pandemic, which shows interesting insights on new habits and consumption experiences post-crisis. In line with the study by Shet (2020), we contribute to this field of literature of consumer behavior by examining the consumer lifestyle during the COVID-19 lockdown in order to explore post-disaster behaviors that people would keep after the lockdown, and finally, we propose a new consumer behavioral profile (see Fig. 1).

7 Limitations and future research

Our analysis has some limitations. First, it is closely connected to the COVID-19 disaster in Italy; therefore, we invite future researchers to study these behaviors in different contexts to understand if the model is replicable. Furthermore, we aimed to raise awareness of the necessity to examine these behavioral issues in depth in complex environments and situations, trying to conceptually classify them into homogeneous elements that shape the four main categories of the new consumer profile proposed in this study.

Future research could be carried out by profiling the sample to identify possible latent clusters; moreover, the consumer perspective and the highlighted consumer behavioral changes provide the opportunity to investigate the firm’s response to the new needs and attitudes.

References

Basu, A. J., & van Zyl, D. J. (2006). Industrial ecology framework for achieving cleaner production in the mining and minerals industry. Journal of Cleaner Production, 14(3–4), 299–304.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

Burnett, J. J. (1998). A strategic approach to managing crises. Public Relations Review, 24(4), 475–488.

Burt, R. S. (1992). Structural holes: The structure of social capital competition. Harvard University Press.

Cancello, R., Soranna, D., Zambra, G., Zambon, A., & Invitti, C. (2020). Determinants of the lifestyle changes during COVID-19 pandemic in the residents of Northern Italy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(17), 6287.

Chesbrough, H., Kim, S., & Agogino, A. (2014). Chez Panisse: Building an open innovation ecosystem. California Management Review, 56(4), 144–171.

COOP Rapporto (2020) available at https://www.italiani.coop/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/PRESENTAZIONE-RAPCOOP2020-web-hd.pdf

Coleman, J. S. (1988). Social capital in the creation of human capital. American Journal of Sociology, 94, S95–S120.

Coleman, J. (1990). Foundations of Social Theory. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Coppola, D. P. (2006). Introduction to international disaster management. Elsevier.

Cozzolino, A. (2012). Cross-Sector Cooperation in Disaster Relief Management (pp. 5–16). Heidelberg: Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management, Berlin.

Dalli, D. (2004). La ricerca sul comportamento del consumatore: lo stato dell'arte in Italia e all'estero. Mercati e competitività.

Del Chiappa, G., Pung, J. M., Atzeni, M., & Sini, L. (2021). What prevents consumers that are aware of Airbnb from using the platform? A mixed methods approach. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 93, 102775.

Deloitte (2020). Il consumatore e la new reality. https://assets.kpmg/content/dam/kpmg/it/pdf/2020/09/Consumer-Behavior-Survey-Report_GlobalFocusItaly.pdf?__hstc=160160738.ae551b36011bed93214e96de1ee2ffb4.1627291293576.1627291293576.1627291293576.1&__hssc=160160738.1.1627291293576&__hsfp=1360741907

Dunning, H., Williams, A., Abonyi, S., & Crooks, V. (2008). A mixed method approach to quality of life research: A case study approach. Social Indicators Research, 85(1), 145–158.

East, R., Singh, J., Wright, M., & Vanhuele, M. (2016). Consumer behaviour: Applications in marketing. Sage.

Eger, L., Komárková, L., Egerová, D., & Mičík, M. (2021). The effect of COVID-19 on consumer shopping behaviour: Generational cohort perspective. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 61, 102542.

Ehrenfeld, J. R. (2000). Industrial ecology: Paradigm shift or normal science? American Behavioral Scientist, 44(2), 229–244.

Feng, Y., Wu, J., & He, P. (2019). Global M&A and the development of the IC industry ecosystem in China: What can we learn from the case of Tsinghua Unigroup? Sustainability, 11(1), 106.

Ferraresi, M. (2020) Interview available at https://www.huffingtonpost.it/entry/mauro-ferraresi-effetto-covid-prima-compravamo-tempo-ora spazio_it_5ec7ddbec5b6cc3a293443f8?ie=&utm_hp_ref=it-homepage&ncid=fcbklnkithpmg00000001&ref=fbph&fbclid=IwAR09FFRz78JsxZ2e0QOlORar-H6oLQH_s-QoAOiuTlvPpuSZ79XZ5afk7vM

Fritsch, M., & Kauffeld-Monz, M. (2010). The impact of network structure on knowledge transfer: An application of social network analysis in the context of regional innovation networks. The Annals of Regional Science, 44(1), 21.

Frosch, R. A., & Gallopoulos, N. E. (1989). Strategies for manufacturing. Scientifi,c American, 261(3), 144–152.

Grossi, P. (2005). Catastrophe modeling: a new approach to managing risk (Vol. 25). Springer Science & Business Media.

Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82.

Guion, D. T., Scammon, D. L., & Borders, A. L. (2007). Weathering the storm: A social marketing perspective on disaster preparedness and response with lessons from Hurricane Katrina. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 26(1), 20–32.

Hesse-Biber, S. N., & Leavy, P. (2010). The practice of qualitative research. Sage.

Hoekstra, J. C., & Leeflang, P. S. (2020). Marketing in the era of COVID-19. Italian Journal of Marketing, 2020(4), 249–260.

Holbrook, M. B., & Hirschman, E. C. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(2), 132–140.

Houston, J. B., Pfefferbaum, B., & Rosenholtz, C. E. (2012). Disaster news: Framing and frame changing in coverage of major US natural disasters, 2000–2010. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 89(4), 606–623.

Iansiti, M., & Levien, R. (2004). The keystone advantage: what the new dynamics of business ecosystems mean for strategy, innovation, and sustainability. Harvard Business Press.

Kim, S., Ham, S., Moon, H., Chua, B. L., & Han, H. (2019). Experience, brand prestige, perceived value (functional, hedonic, social, and financial), and loyalty among GROCERANT customers. International Journal of Hospitality Management, 77, 169–177.

Lamont, M., White, P. (2005),Workshop on Interdisciplinary Standards for Systematic Qualitative Research, in Cultural Anthropology, Law and Social Science, Political Science, and Sociology Programs, National Science Foundation, Available from: https://www.nsf.gov/sbe/ses/soc/ISSQR_rpt.pdf .

Lin, H. C., Bruning, P. F., & Swarna, H. (2018). Using online opinion leaders to promote the hedonic and utilitarian value of products and services. Business Horizons, 61(3), 431–442.

Marshall, M. I., & Schrank, H. L. (2014). Small business disaster recovery: A research framework. Natural Hazards, 72(2), 597–616.

Mason, A., Narcum, J., & Mason, K. (2020). Changes in consumer decision-making resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Customer Behaviour., 19, 299–321.

McFarlane, A. C., & Norris, F. H. (2006). Definitions and concepts in disaster research. Methods for Disaster Mental Health Research, 2006, 3–19.

Mehta, S., Saxena, T., & Purohit, N. (2020). The New consumer behaviour paradigm amid COVID-19: Permanent or Transient?. Journal of Health Management, 22(2), 291–301.

Mikalef, P., Boura, M., Lekakos, G., & Krogstie, J. (2019). Big data analytics and firm performance: findings from a mixed-method approach. Journal of Business Research, 98, 261–276.

Morrish, S. C., & Jones, R. (2020). Post-disaster business recovery: An entrepreneurial marketing perspective. Journal of Business Research, 113, 83–92.

Naeem, M. (2020). Understanding the customer psychology of impulse buying during COVID-19 pandemic: implications for retailers. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management.

Neal, D. M., & Phillips, B. D. (1995). Effective emergency management: Reconsidering the bureaucratic approach. Disasters, 19(4), 327–337.

Nguyen, H. V., Tran, H. X., Van Huy, L., Nguyen, X. N., Do, M. T., & Nguyen, N. (2020). Online book shopping in Vietnam: The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic situation. Publishing Research Quarterly, 36, 437–445.

Nomisma (2020). Un Italiano su tre preferisce uno stile di vita corretto. Available at https://www.nomisma.it/stili-di-vita-corretti/

OMS (2021) available at https://www.salute.gov.it/portale/nuovocoronavirus/dettaglioContenutiNuovoCoronavirus.jsp?lingua=italiano&id=5338&area=nuovoCoronavirus&menu=vuoto

Overby, J. W., & Lee, E. J. (2006). The effects of utilitarian and hedonic online shopping value on consumer preference and intentions. Journal of Business Research, 59(10–11), 1160–1166.

Park, I., Sharman, R., & Rao, H. R. (2015). Disaster experience and hospital information systems: An examination of perceived information assurance, risk, resilience, and his usefulness. Mis Quarterly, 39(2), 317–344.

Pearson, C. M., & Clair, J. A. (1998). Reframing crisis management. Academy of Management Review, 23(1), 59–76.

Perry, M. (2007). Natural disaster management planning. International Journal of Physical Distribution & Logistics Management.

Porter, M. E. (1991). Michael E. Harvard Business School Press.

Pullen, A., de Weerd-Nederhof, P. C., Groen, A. J., & Fisscher, O. A. (2012). SME network characteristics vs. product innovativeness: How to achieve high innovation performance. Creativity and Innovation Management, 21(2), 130–146.

Sheth, J. (2020). Impact of Covid-19 on consumer behavior: will the old habits return or die? Journal of Business Research., 117, 280–283.

SwissRe Institute (2020). Article available at https://www.swissre.com/institute/research/topics-and-risk-dialogues/health-and-longevity/covid-19-and-consumer-behaviour.html

Taleb, N. N. (2007). The black swan: The impact of the highly improbable (Vol. 2). Random house.

Taleb, N. N., Goldstein, D. G., & Spitznagel, M. W. (2009). The six mistakes executives make in risk management. Harvard Business Review, 87(10), 78–81.

Tashakkori, A., & Creswell, J. W. (2007). The new era of mixed methods.

Vaughn, P., & Turner, C. (2016). Decoding via coding: Analyzing qualitative text data through thematic coding and survey methodologies. Journal of Library Administration, 56(1), 41–51.

Wankmüller, C. (2021). European disaster management in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Mind & Society, 20(1), 165–170.

Wasserman, S., & Faust, K. (1994). Social network analysis: Methods and applications. Cambridge university press

Zhai, Q., Cao, X., Mokhtarian, P. L., & Zhen, F. (2017). The interactions between e-shopping and store shopping in the shopping process for search goods and experience goods. Transportation, 44(5), 885–904.

Acknowledgements

The authors did not receive support from any organization for the submitted work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sorrentino, A., Leone, D. & Caporuscio, A. Changes in the post-covid-19 consumers’ behaviors and lifestyle in italy. A disaster management perspective. Ital. J. Mark. 2022, 87–106 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s43039-021-00043-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s43039-021-00043-8