Abstract

Research Question

What are the characteristics of intimate partner homicide in Denmark that may inform more accurate prediction and prevention of such crimes, and how is knowledge of those facts distributed across families, police and other agencies?

Data

All Danish police data on all 77 cases of intimate partner homicide (IPH) reported over 11 years (2007 through 2017) in 10 of the 12 Danish Police Districts were coded by the first author, comprising 75% of all known IPH cases in Denmark for those years and 100% of the cases in Districts that allowed access to their investigative files.

Methods

Potentially predictive variables were selected for coding based on similar studies recently completed in the UK and Australia, with comparisons made between these Danish results and the prior findings. Special emphasis was placed on which potential predictors had been known by some organisation or person, but never reported to police until after the homicides had occurred.

Findings

Characteristics of IPH cases in this study are remarkably similar to those found in the UK studies, starting with the nearly identical rates of IPH per 100,000. The Danish data show even greater prevalence of male offenders having discussed, threatened or attempted suicide prior to killing their intimate partner (52%) than in the all-England sample (40%). Danish IPH cases were even more likely (71%) than the Thames Valley cases (54%) to have had no prior recorded police contact as a couple before the IPH incident. In Denmark, parties other than the police had prior knowledge of domestic abuse in almost half (47%) of the murders, including public agencies (22% of IPH), but did not share that information with the police.

Conclusions

In Denmark as in the UK, police have no prior contact with most intimate couples suffering a homicide. While suicidal tendencies are highly prevalent in such cases, police have no legal framework for obtaining intelligence about such risk factors from health and social agencies. These findings show that in Denmark as elsewhere, creating a duty by other public agencies to share information might improve prediction and prevention of domestic homicides.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the summer of 2004, the first author of this article was an investigator in a police district just outside Copenhagen. One morning, many police cars were sent to a housing estate where several shots had been fired. On arrival, police discovered that a man had shot and killed his former girlfriend. He had kicked in her door and chased her out of the apartment to another stairwell in the estate. On the route there, he had shot at her, and in the stairwell he killed her with several shots. After this, he committed suicide sitting on the stairs next to her body.

This was the culmination of a night in which he had been at her apartment several times and she had called the police. The couple had separated some time in advance of this episode, and the murderer had been trying to win his victim back. That night, a police patrol car came to the site in the very early morning, but he was no longer there. Some hours later, the shots were fired.

The first author was part of the team assigned to inform the murderer’s 15-year-old son (by a previous marriage) of the death of his father. It was decided to first inform the mother of the son so that she could help with this difficult task. She agreed to ride in the police car to the house where the murderer and her son had lived together. The mother tried to reach her son by phone but he did not answer. Arriving at the house, the police officers used the keys found on the body of the murderer. The mother had told police that there was an aggressive dog in the house who knew her, so she should enter ahead of the police. Shortly after entering, the police heard the mother screaming from the attic. Running to the attic bedroom of the son, the first author encountered a strong smell of iron in the air—which often accompanies large amounts of blood.

In his own bed, the son lay shot and killed, and next to him his dog was also shot dead. Apparently, the father had killed his son and dog, then driven back to the former girlfriend to commit yet another homicide and his own subsequent suicide.

This episode created the reaction that is very often heard in connection with intimate homicides: ‘this case should have been predicted and prevented.’ Someone should have done something to help the offender and the victims. In Denmark, there are about 10 homicides every year involving present or former intimate partners. Quite often, there is an uproar from relatives and friends in the media afterwards, which points out that many public authorities knew of a conflict and previous violence, threats and stalking behaviour.

The ambition to predict and prevent has resulted in several tools intended to help the authorities to pinpoint those couples who were the most likely to continue the abuse and perhaps escalate into serious violence or homicide. But what, if any, predictors are accurate enough to be used to focus the efforts of police and others? While a growing body of evidence on that question can be found in other countries, there has been no systematic evidence yet reported for Denmark.

Research Questions

The primary aim of this study is to determine whether there are any clear predictors for intimate partner homicide in Denmark, to the limited extent that they can be identified by looking at such cases without any matched control cases. The research is guided by previous similar ‘numerator-only’ studies overseas, which have suggested clearly elevated risks of persons committing IPH if they have expressed suicidal thoughts or threats, or even attempted suicide. Persons who have had a psychiatric diagnosis and people with histories of substance abuse are also found overseas to be disproportionately present in cases of homicide and serious violence in intimate partnerships.

Building on this prior work, this study particularly attempts to replicate the Bridger et al. (2017) analysis of 188 cases of intimate partner homicide (IPH) in England and Wales, in which a list of potentially predictive characteristics was examined. Our objective is to explore similar cases from Denmark using similar variables to the extent possible.

The present study explores all of the 77 IPH cases from the years 2007 to 2017 that were investigated in 10 out of 12 police districts in Denmark. Our key question is whether the 77 cases offer evidence of characteristics which appear highly disproportionate in relation to such characteristics in the broader population, such as unemployment or threats to commit suicide. A further question, by implication, is this: who knew the facts of those characteristics, including prior domestic abuse, that were not known to the police? Answering those questions, even provisionally, will lead to the policy question of how more of that information might be reported to police before a murder occurs, rather than afterwards.

Prior Evidence on Predicting Intimate Partner Homicides

Bridger (2015) and Bridger et al. (2017) examined 188 IPH cases committed in England and Wales in 2011–2013 seeking possible predictive characteristics of the victim, the offender, their relationship and the homicide itself. Victim and offender sociodemographic variables examined included gender, age, ethnicity, occupation, substance abuse and intoxication at the time of homicide. Information on mental health issues, victimisation and criminality were reviewed for both parties. The criminality of the offender was examined on specific crime types such as use of weapons, sexual offences, harassment and stalking, threats to kill, strangling/choking, breach of bail/injunction and violence towards children and animals. The study gave special scrutiny to what was known, by whom and when: either police, other public authorities or friends and relatives of the couple. Their relationship was described via category, length, status at the point of homicide and presence of children both from the common relationship or other relationships and the residence of these children at the time of the homicide. The offence was described by time, place, location, number and relationship of additional victims, number, role and relationship of possible co-accused and method of killing and weapon used.

In previous studies by Thornton (2011, 2017) and Chalkley (2015), Chalkley and Strang 2017), pre-offence suicidal indicators seemed to be a promising predictor. That observation was confirmed by Bridger (2015) especially for male offenders, who had shown signs of suicidal indicators in 40% of the murderers of females, and in 28% for female offenders who murdered males. Suicidal indications were less prominent for victims, with an overall proportion of 9% having had suicidal indicators (male victims at 27% and female victims having contemplated suicide at some stage in 6% of the cases). All of these findings are given extra force by the low rates of suicide attempts in the general population that does not commit IPH.

Bridger et al. (2017) based their study on an admittedly incomplete sample. While the powers of a Domestic Homicide Review (DHR) to compel production of evidence are substantial, they do not extend to insuring that all DHRs are actually completed as required. Bridger et al. (2017) reported that the Domestic Homicide Review (DHR) was completed in only 52% of the IPH cases, despite such reviews being required by law. Of the DHRs that were completed, there were four main conclusions: (1) there is a lack of sharing information on possible predictors of IPH between public authorities and the police, (2) there is a lack of a good and commonly agreed understanding of what constitutes abuse, (3) the risk assessment processes conducted in advance were imprecise, and (4) there is a severe lack of focus on possible perpetrator needs when deciding on how to handle cases.

Repetition and Escalation Fail as Homicide Predictors

Most risk assessment tools for IPH rely on the assumptions that domestic violence is ongoing, and serious violence such as murder is the result of escalation. That assumption suggests that police or others usually have an opportunity to take action at an early stage in the escalating seriousness of domestic abuse before it turns worse. Yet the available evidence does not support that assumption.

Across more than 80,000 cases, neither Bland and Ariel (2015) in Suffolk nor Barnham et al. (2017) in Thames Valley found evidence of escalation in the severity of harm from domestic violence as couples reported more and more incidents; if anything, the pattern was one of declining severity rather than increasing harm as the number of repeat incidents by each reported offender increased. Moreover, Thornton (2011, 2017) and Chalkley (2015); Chalkley and Strang 2017) showed that across both lethal and near-lethal cases, only 45% (in Thames Valley) and 63% (in Dorset) of the couples in those murderous intent cases had prior police contact before the incident. Such a large proportion of cases with no previous police contact prevented police from making any risk assessment at all, let alone an accurate prediction.

In a setting somewhat closer to Danish context, Dagenbrink (2017) analysed 25,065 Swedish cases of domestic violence (both physical and psychological) in both heterosexual and homosexual couples. After the first police contact, there was a 2-year follow-up with a focus on new incidents of domestic violence or similar nature. Her study showed that only 90% of the couples had only one incident reported to police. Among the 10% of the couples who had one or more further police contacts for similar incidents, only about 2% of the couples had three or more episodes known to police in the follow-up period. It was also noted that only 1% of the Swedish cases showed escalation in severity over time. As in Bland and Ariel’s (2015) study of Suffolk in England, there was no pattern of escalation in Sweden.

Danish Context

The Danish context has many similarities to the UK in patterns of IPH, starting with the rate of such crimes per capita. Bridger 2015, p. 14) report on both total homicide and IPH in England and Wales. According to these statistics, there were about 530 homicides of all kinds and 110 IPH in 2013/14 in a population of 57 million inhabitants. In Denmark, there are approximately 50 homicides per year and 10–12 IPH per year (Rasmussen et al. 2016) with approximately 5.8 million inhabitants (Danmarks Statistik, Official Office for Statistics in Denmark), making the two nations comparable in both total homicide and the IPH rate per 100,000. Rasmussen et al. (2016) studied 30 Danish IPH cases from 2009 to 11. Their analysis suggested that prior physical violence was not as common in IPH cases as prior psychological violence such as stalking, harassment, threats to life and strong controlling behaviour by offenders over victims. Separation also appeared to be very common in these Danish IPH cases. Contrary to Bridger’s (2015) findings, alcohol abuse did not seem to be very common among IPH offenders.

Data

In Denmark, all residents have a Central Persons Register Number (a ‘CPR’). The CPR number is used by all public authorities to identify individual residents for any purpose. The CPR makes it possible for the police to find information on every person from every public agency working with that person, as well as some private companies. Having a CPR for the current study was useful because it helped to find information in two key police data bases called POLSAS and KR.

POLSAS

Danish police implemented POLSAS, the Police Case Administration System, in 1996. This system contains information on all cases reported to or made on initiative by the police. The information includes the offence, the persons involved, their respective roles, the investigative material and the decisions made during the cases such as charge, indictment, conviction or other judicial steps. POLSAS includes all IPH cases back to 1996 in which the victim and offender may have had prior offences or victimizations recorded. From these POLSAS case files, this study assembled information on the lifelong criminality and victimisation of the victim and offender, as well as the investigative material on the IPH incident, such as police reports, autopsy reports, psychiatric evaluation and more personal characteristics.

KR

Information on all charges and convictions is gathered in the Criminal Records (KR, Danish abbreviation) which came into use in 1978. Information in this rather old system is quite brief, describing the legal elements of the offence and the judicial decision made in the individual case. But information in KR is also subject to being erased according to the severity of the case and the subsequent statute of limitation. Some cases will be erased as soon as 3 years after disposal, but the most serious cases are kept for the lifetime of the person convicted. Cases in KR are erased upon the death of the person, so none of the victims in this study have information in KR. Even for the offenders in this study who survived their incident of murdering an intimate partner, the KR information on them will in many cases not be complete when using KR.

Identification of and Access to Cases

IPH is the overall subject and search criteria in this study, but how is intimate partner and homicide defined? In the Danish Penal Code section 237, homicide is defined as: ‘The person who kills another person is to be punished with imprisonment of between 5 years and life time.’ What is not mentioned in this legal text is the intent, and intent has to be proven in order to convict someone of homicide. There might be cases where the death of one person was not the result of an intended action, but as an unfortunate and unintended result of an action aiming at doing less harm than death. In this study, it is the intention to look at cases where intent to commit homicide was proven or indicated to such a degree that there is a charge, indictment or conviction (both preliminary and final) with homicide.

This study defines an ‘intimate partnership’ as a man and woman who are or have been romantically involved. There is no demand to the length of the relationship or the number of times the parties have been together. The romantic involvement must be mutual, so as to exclude cases of stalking. Homosexual relationships have been excluded as they might contain dynamics not representative of the overall group of relationships. It should be noted, however, that no true IPH in homosexual relationships was found during the identification process.

Methods

From POLSAS, a list of all homicide cases in the years 2007–2017 was drawn containing the case number, time of reporting, time of the offence, address of the offence and a short resume of the case. The first author reviewed the resume in each potentially eligible case. On the basis of the content of the resume, many but not all cases could be either included or excluded in the study. Many of the case resumes had very general descriptions of the circumstances of the facts. These cases had to be scrutinised further to make sure if they adhered to the definitions mentioned above, initially by making sure that victim and offender were of opposite genders. Then, the remaining cases were sorted by reading central written reports such as the recommendation to the crown prosecutor and updated decisions such as convictions. For the oldest cases, the first author used the internet to search for names of offenders and victims. This last measure was necessary as there was no longer access to the written reports in POLSAS.

After having obtained support from the National Centre of Investigation and National Centre of Crime Prevention, a list of cases from each police district was formed and sent to the district heads of investigation. A description of the purpose of the study accompanied a request for a data access agreement between the police district and the author, as an application for access to see the physical cases. An important part of the data access agreement was the guarantee that the anonymity of the offender and victim was to be protected and not subject to publication.

Access to the hard copy paper case file was necessary because much of the investigative material had not been uploaded to POLSAS. Access to these files was granted by 10 of the 12 police districts. The total number of relevant cases was 77, with final convictions in 59 of these cases. Only indictments were on file in two of the cases; only charges were found in one, pending final statement on mental state of perpetrator. In the remaining 15 cases, the offender committed suicide before being prosecuted, but the investigations all concluded murder by partner (present or former) and subsequent suicide.

Arrangements were made with the police districts to view the cases in their respective headquarters. Information on criminality and victimisation was obtained by a search of both POLSAS and KR forming the best possible combined knowledge of this at the hands of the police.

Extracting Data from Cases and Police Systems

The first author read all accessible investigative material in the homicide cases and extracted data with the help of a case coding sheet. This codesheet, to the extent possible, was replicated from Bridger (2015) and appears in Rye (2018: appendix I). By treating the process as a structured interview with the investigative material posing as the interviewed person and the case coding sheet as the interview guide, the author worked through the written reports filling out the sheet as the information was found. There were variables covering characteristics of the victim, the offender, the relationship and the offence itself. The definition and measurement of these variables were to the extent possible replicated from Bridger (2015) but in a number of variables Danish context demanded a somewhat different definition and measurement to make sense. Details of coding may be found in Rye (2018).

Criminality and Victimisation

Information on victimisation and criminality is mainly found in KR and POLSAS but could also be revealed in statements by family, friends etc. In these cases, the information is only put in the data coding sheet if there is corroborating information on it, i.e. more statements telling same story or information from public services supporting the statements.

Mental Health, Suicide Indicators and Isolation

Information on mental health issues and psychiatric diagnosis was gathered from statements from General Practitioners and from the historical part of the psychiatric evaluation. It was supplemented by information from family, friends and other professionals.

Suicide indicators before the IPH offence as well as post-offence suicide and attempted suicide are all documented in the files through witness statements, psychiatric evaluation, information from POLSAS, investigative findings and observations.

Isolation was established through statements from persons or public services to whom the victim had revealed this feeling or who had witnessed the process of isolation from the usual social network of friends, family or colleagues.

Findings

Personal Characteristics

In the 77 cases, there were 65 male offenders (84%) and 12 female offenders (16%). Offender’s age varied between 20 and 88 years; divided into gender, male offenders were between 22 and 88 years old, while female offenders were between 20 and 71 years old. There is a peak in male offenders in the age groups between 25 and 49 years with the highest peak in the age group 40–44 with 11 persons. Age of the victim overall varies between 17 and 84 years old, and when split into gender these too span 26–74 years for male victims and 17–84 years for female victims. In female victims, there is a peak growing from the first age group culminating at 12 victims (18.46%) in the age group 35–39 and descending until age group 50–54. After this age 50–54, there is a small rise in age until the age group 60–64, after which the small amount of cases make it difficult to see a clear pattern.

As seen in Table 1, there is a high frequency of white north Europeans among offenders overall and gender wise and a noticeable representation of 16.92% (11/65) Middle Eastern male offenders and 16.67% (2/12) are Greenlandic female offenders. The female offender group consists solely of white North Europeans and Greenlanders.

When looking at the representation of ethnicities among victims in Table 2, there is an almost similar overall frequency of white North Europeans. It can be further noticed that there is a 100% (12/12) frequency of white North Europeans male victims whereas the spread among female victims is much more diverse and somewhat resembles that of male offenders—their counterpart.

When looking at the group of male offenders, it is seen that this group has 34% (22/65) in employment and 65% (42/65) without. One of the male offenders is in the group of professionals/managerial, and the main body of employed male offenders is clerical/skilled with 14 individuals. In the group of male offenders without employment, unemployed dominates with 24 individuals followed by retired with 17 individuals (Table 3).

ercent.

Female offenders have an unemployment rate of 58.33% (7/12). Most of the employed female offenders are unskilled (25.00%, 3/12). One had home duties, two were retired and four are unemployed (Table 4).

Table 5 shows that two thirds of male victims were unemployed, two of whom were retired.

The much larger group of female victims were according to occupation divided into 41.54% (27/65) in some sort of employment, 46.15% (30/65) with no employment and 12.31% (8/65) with unknown occupation. In the employed subgroup, there were two professional/managerial, 15 clerical/skilled and 10 unskilled. Among those outside employment, there were seven students, 12 retired and 11 unemployed (Table 6).

Substance Abuse and Intoxication

Forty-two percent of male offenders (27/65) were abusing one or more substances. Alcohol and hashish were the most common addictions, at (21/65) and (10/65), respectively. Female offenders had a slightly higher frequency of addiction at 50.00% (6/12), with alcohol abuse for (5/12) and hashish (2/12) the named substances.

In assessing intoxication during the act of homicide, the study looked for both eyewitness statements and toxicology reports obtained after the apprehension of the offender. The result was that intoxication was stated in 27 of the 77 cases; it was unknown in another 29, whether the offender had been intoxicated at the time of homicide, while 21 were reported to have been sober.

How many of the victims were then intoxicated at the time of the homicide? Overall, 55% (42/77) were not intoxicated, 34% (26/77) were, and in the remaining 12% (9/77) of cases it was unknown whether the victim had been intoxicated.

Mental Health

In most homicide cases, a psychiatric evaluation is made for the purpose of establishing whether the offender was mentally competent during the homicide, but it was not always fully, or even partly, available to this research project. For the offenders, the first author was given evidence that 54% (49/77) had a diagnosis for a psychiatric condition. Depression was diagnosed in 34% (26/77), anxiety and schizophrenia were both present in 13% (10/77) and other diagnoses were made of 30% of the offenders. Other diagnoses included PTSD, dementia, personality disorder, compulsive thoughts and bipolarity. Many of the cases contained multiple diagnoses combining the abovementioned findings.

This partial evidence showed that at least 60% of male offenders (39/65) had one or more psychiatric diagnoses. Depression (26%) was the most common diagnosis; schizophrenia (12%) was the second. Other psychiatric diagnoses were evident in 34% (22/65) of the cases.

There was a higher frequency of psychiatric diagnoses known to have been made for the female offender cohort, with 83% (10/12) diagnosed, with at least 75.00% (9/12) with depression and 25.00% (3/12) having suffered anxiety.

Fewer victims (18/77) than offenders had available psychiatric diagnoses. Depression was the more common victim diagnosis at 14% (11/77). Anxiety was diagnosed in 6% (5/77) of the victims prior to their death.

Suicidal Indicators

Suicidal indicators were defined as thoughts and threats of suicide or actual attempts to commit suicide before the IPH event. Over half of the offenders (53%, or 41/77) had met that definition prior to the IPH. When divided by gender, the rate was slightly higher among female offenders than male offenders, 58% of female offenders (7/12) had such a record compared to 52% (34/65) for male offenders.

As with psychiatric diagnosis, frequency of suicidal indicators was lower among victims than in the offender groups. Overall, 18% (14/77) of victims were known to have suicidal indicators, 42% (5/12) for male victims and 14% (9/65) for female victims.

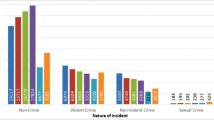

Prior Crimes by Offenders Against Victims

The key question for policing IPH is in how many cases police had any record of domestic abuse crimes by the IPH offender against the IPH victim. Table 7 shows the results of a POLSAS search for prior crimes in the exact dyad of offender and victim in each of the IPH cases, accessed by the victims’ identity. In 71% (55/77) of all IPH cases, POLSAS shows no prior record of domestic abuse against the IPH victim by their IPH offender anywhere in Denmark. For male IPH victims, the rate of no prior DA victimisations from the IPH offender was 83% (10/12); for female IPH victims, the rate of no prior victimisations from the IPH offender was 69% (45/65).

Other searches of POLSAS for all kinds of crimes against all victims showed higher rates of prevalence. Across all offenders, 54% (42/77) had been charged with one or more crimes previous to the IPH. But not all crimes committed are reported to police before the IPH; more crimes emerge in the investigation after the IPH. When reported crimes and offences known to friends, family, colleagues and other public authorities are combined, some crime types stand out as prominent.

For male offenders, 57% (37/65) were ultimately recorded as having made threats to kill someone, against either the ultimate victim of the case or others. Crimes involving weapons were ultimately known for 26% (17/65) of the male offenders; 25% had committed stalking behaviour and 25% (16/65) had committed choking/strangling.

Among female offenders, 58% (7/12) had previously been charged with one or more crimes. At the same time there is evidence in the investigative material that 42% (5/12) of the female offenders had threatened someone’s life and 25.00% (3/12) had committed a weapons related crime.

Prior Crimes Among Victims

The case material and police data bases reveal that 67% of (8/12) male victims have been charged by the police for some crimes, while 17% (2/12) had been charged with domestic abuse type crimes (one male IPH victim charged once and one male IPH victim charged four times). Out of these 12 male victims, 2 of them had previously been the victim of domestic abuse or violence at the hands of the IPH offender who killed them, and in one case the violence was committed using a bladed weapon. A total of 33% (4/12) of the male victims had revealed to people other than the police that they had been subjected to domestic abuse assaults prior to the IPH. Yet there were no records of previous victim injury at the hands of the ultimate offender.

The female IPH victims had police records of previous victimisation of domestic abuse-type crimes or incidents against them recorded in 29% (19/65) of the female victims’ cases. Yet only 4 of the 19 female IPH victims with prior victimisations had reported a physical injury to public agencies. In these cases, one report was to the emergency room at the hospital and three cases were reported to the police. This information was shared more widely away from public record. As revealed after the IPH, almost half of the female victims (32/65) had disclosed domestic abuse assault to others than police. None of the female IPH victims are known to have committed domestic abuse or violence, but 23% (15/65) of them had been charged with some other violation of the penal code prior to their death by IPH.

Relationship Characteristics

The type of relationship is coded on the basis of either a current or prior intimate relationship at the time of the homicide. When described as co-habiting or not, Table 8 shows that 68% (52/77) of the couples either were or had been co-habiting, and 32% had never co-habited.

Most of the relationships in these homicides are relatively new, with over half (53%) less than 7 years in length. Table 8 shows the distribution of length of relationship when using the intervals of Bridger (2015); the length of relationship is unknown in one case and excluded. The table also shows that 21% (16/76) IPHs occurred within the first year, while only 31% (23/76) occurred after 17 years or more together, ranging up to 65 years in the relationship (Table 9).

Pregnancy and Children

The data showed that only one of the 65 female victims was pregnant at the time of the homicide. But as only 44 of the 65 female victims were of likely age for child-bearing (between 15 and 44 years old), the frequency of pregnancy within that subgroup is 2.27% (1/44).

Out of the 77 relationships examined, 43% (33/77) had children from the relationship, in 35% (27/77) the offender had children from other relationships and in 36% (28/77) the victim had children from other relationships. In 29% (22/77) of the relationships, the couple had mixed different mixes of these categories of children. In 16% (12/77), there were no children.

Offence Characteristics: Method of Killing and Weapons Used

The most common method of killing by male offenders was strangulation. This method is present alone or with other methods in 37% (24/65) of male offender cases. Stabbing and cutting with bladed weapons is the second most used method that males applied, in 34% (22/65) of cases. Men used firearms to kill in 22% (14/65) of IPH cases.

Among female offenders, stabbing and bladed weapons were the most common method of killing, present in 75% (8/12) of cases. Blunt force was used by women offenders in two cases; the other two killed by firearms.

Pre-IPH Behaviour by Offenders

The overall picture of the offender behaviour immediately prior to the IPH is one of low disclosure of potential intent and a low degree of preparation. Fully 68% (52/77) left no evidence of offence disclosure to witnesses; 60% (46/77) revealed no preparation for the act. Among the 65 male offenders, 20 (31%) had revealed thoughts of committing serious harm or murder. Among the 12 female offenders, four disclosed thoughts of committing harm or murder and three (25.00%) made preparations for the homicide.

Motivating Factors

Among male offenders, the most highly represented motivating factors were jealousy, separation, argument and mental disorder. Jealousy was part of the motivational complex in 45% (29/65) of cases and separation was present in 43% of male offender (28/65) cases. In 25 (38%) of male offender cases, an argument seems to have played a role in the homicide happening. In 19 (29%) male offender cases, there were indications that mental disorder with the offender played a vital role in the causation of the murder. Other motivational factors are each mentioned in eight or fewer cases.

The 12 female offenders seem to have been motivated by argument, self-defence/provocation and drunken altercation. Other motivations included feeling trapped in the relationship, fear of exposure of other criminality and long time strain. The events of argument (nine cases) and drunken altercation (four cases) were prominent among female offenders. There were also elements of self defence in eight (67%) of the cases.

Discussion

Just as Bridger (2015) found in his study of English domestic homicide reviews, this study finds that most IPH crimes in Denmark were committed by offenders with high rates of suicidal indicators, unemployment, substance abuse and mental health problems. Both countries also have very high prevalence of police receiving no prior reports of domestic abuse within the dyad before the IPH occurs.

In the present study, it was shown that only 29% of IPH offenders have any prior police record of having abused their IPH victims before the homicide occurred. Thus, almost three fourths of all the relationships would never have been given the opportunity to get help from police to avoid the homicide. But in many of those cases, knowledge of the domestic abuse patterns in the relationship was held by others outside the police.

In almost half the cases, there was disclosure from the victim of domestic abuse by the offender to others than the police. In the 36 cases with victim disclosure to non-police audiences, this knowledge came into the hands of some public authority in 17 cases. In the other 19 cases, the knowledge remained solely with family, friend or colleagues. It should also be noted that there were one or more eyewitnesses to prior domestic abuse in the relationship in 28 (36%) of the cases.

Threat to life is one of the most frequent characteristics of offenders prior to committing IPH, with 55% (42/77) of the perpetrators having committed just that offence against either the partner or others. Yet once again, this finding is based on knowledge compiled from many sources only after the IPH; only 13 of those threats-to-kill cases were reported to police.

Going from some level of assault in a prior offence up to homicide as the final offence could with no doubt be described as an escalation in violence. Since ongoing violence preceded up to half of the IPH cases, that is evidence of escalation of escalation that might have been predicted. But since that information was never made available to police before the IPH, police could not use it to predict or prevent these homicides.

Research Limitations

This study originally aimed at making an exploration of the entire Danish population of IPH cases over a substantial period of time. But as access was denied by two police districts, it remains a 75% sample of all known Danish cases in the time period. At the same time, it should be noted that the two districts were situated in two different parts of the country. One was mainly in an urban area and the other mainly rural. They each resemble other police districts included in this study, at least in population size and demography. The two police districts denying access, unfortunately, both had a relatively high number of IPH cases. Between them, they contributed approximately a fourth of all cases (25/97) in the years 2007–2016. So the absence of data on the 25 cases from these two districts might have influenced the findings of this study. This can be mended if they at any point decide to give access to the cases that can then be transferred to the spread sheet for this or future studies in order to make new statistical analyses on the dataset.

Conclusion and Policy Implications

The study has documented a major challenge faced by police in preventing escalation in harm among couples at risk of intimate partner homicide. That challenge is the fatal reluctance of families and friends to share their knowledge about abuse within these relationships. Absent their providing that information, in ways that can contribute to a single source, police will likely have no idea about that violence in over 70% of IPH cases until the fatality occurs. Since almost half of the victims in our sample of IPH cases had at some point disclosed the problem to someone close to them, or to another public authority than police, there may be room to create a public communications strategy to encourage more third-party reporting by members of the public.

There may also be room to encourage more sharing of the crucial knowledge which lies with other public authorities. The challenge to such sharing is under intense scrutiny in these times of the European GDPR (General Data Protection Regulation). Yet there is also a clear concept of duty to prevent loss of life. In Denmark, there is a duty under law to report if children are suspected to be victims of abuse or maltreatment. Also, according to The Public Administration Act and the Administration of Justice Act, there are multiple possibilities to share information among public agencies in order to protect young people and children from working their way into a criminal lifestyle.

Yet no such possibilities exist when dealing with adults. In most cases involving adults, the bar of justification for inter-agency fact-sharing is set much higher: there must be evidence of fear of loss of life, very serious crime or threats to justify any agency sharing with the police this study’s evidence-based numerator factors as a concern about potential IPH. It is rare that the early signs of domestic problems will reach the standard of proof required. The findings of this study, however, could add several dimensions to the basis for inter-agency sharing information about potential IPH cases. These dimensions could combine such apparent risk factors as suicidal threats by persons who are unemployed and diagnosed with depression. Such ‘statistical’ evidence might then enhance the possibility to share information.

The other source of hidden knowledge about these numerator-only factors is the couples’ social networks: family, friends and colleagues. Among the vast majority of cases in this study that did not come to police attention, more than half of those generated informal social network awareness of the problem—when such people were the only ones to have been told by the victim or witnessed the abuse. In just under a fourth of all 77 cases, the disclosure of abuse was given solely to these persons nearest to the victim.

It is, to be sure, difficult to ‘rat’ on someone that you know. Yet such difficulties can be changed by cultural transformations, just as they were with drinking and driving. The first author grew up in the country side, in a community where neighbours knew who used their car even when their drinking posed a threat to all others on the road. This tolerance has disappeared completely. Today, drunk driving is deemed as one of the most despicable acts a driver can commit. Now, many neighbours report drunken drivers to the police if they have not themselves prevented the act. Developing the same cultural response towards domestic abuse could be the result of a similar kind of strategic communication plan that was used in public campaigns against drunk driving.

This study now establishes a list of characteristic of the persons who suffer homicide in their intimate relationships. These findings could have relevance in the continuing evaluation of any couples in danger of continuing domestic abuse or violence. There is a large task in adding hidden knowledge to police capacity to predict IPH, but there is every reason to do accomplish it.

The boy in the attic would have been 30 years old this year.

References

Barnham, L., Barnes, G.C. and Sherman (2017) ’Targeting Escalation of Intimate Partner Violence: Evidence from 52,000 Offenders. Cambridge Journal of Evidence-Based Policing, 1(2 and 3), 116-142

Bland, M., & Ariel, B. (2015). Targeting escalation in reported domestic abuse: Evidence from 36,000 callouts. International Criminal Justice Review, 25(1), 30–53.

Bridger, E. (2015) ‘A descriptive analysis of intimate partner homicide in England and Wales 2011–2013. M.St. thesis in applied criminology and police management, University of Cambridge.

Bridger, E., Strang, H., Parkinson, J., & Sherman, L. W. (2017). Intimate partner homicide in England and Wales 2011–2013: pathways to prediction from multi-agency domestic homicide reviews. Cambridge Journal of Evidence-Based Policing, 1(2 and 3), 93–104.

Chalkley, R. (2015) ‘Predicting serious domestic assaults and murder in Dorset. M.St. thesis in applied criminology and police management, University of Cambridge.

Chalkley, R., & Strang, H. (2017). Predicting domestic homicide and serious violence in Dorset: a replication of Thornton’s Thames Valley Analysis. Cambridge Journal of Evidence-Based Policing, 1(2 and 3), 81–92.

Dagenbrink, M. (2017), Patterns of reported domestic abuse in Sweden: repetition and escalation for two years after initial police contact, M.St. thesis in applied criminology and police management, University of Cambridge.

Rasmussen, N., Norregard-Nielsen, E. and Westermann-Brandgaard, N. (2016), Forebyggelse af drab og dodelig vold i nwre relationer (Prevention of homicide and lethal violence in close relations, translation by author of this thesis), Kobenhavn.

Rye, S. (2018) ‘A Descriptive Analysis of Intimate Partner Homicide in Denmark 2007-2017’, M.St. Thesis in Applied Criminology and Police Management, University of Cambridge

Thornton, S. (2011) ‘Predicting serious domestic assaults and murder in the Thames Valley. M.St. thesis in applied criminology and police management, University of Cambridge.

Thornton, S. (2017). Police attempts to predict domestic murder and serious assault: is early detection possible yet. Cambridge Journal of Evidence-Based Policing, 1(2 and 3), 64–80.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Rye, S., Angel, C. Intimate Partner Homicide in Denmark 2007–2017: Tracking Potential Predictors of Fatal Violence. Camb J Evid Based Polic 3, 37–53 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41887-019-00032-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41887-019-00032-0