Abstract

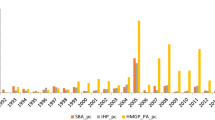

This paper examines the impacts of floods and hurricanes on U.S. county government finances. Using a novel event study model that allows for heterogeneous treatment effects, we find that a flood or hurricane presidential disaster declaration (PDD) lowers tax revenue but increases government spending and intergovernmental revenues. Compared to flooding, hurricanes result in much larger repercussions on both revenues and borrowing. Our results also suggest disparate patterns of disaster-induced long-run fiscal impacts in counties with different socioeconomic conditions. Counties with lower incomes or greater social vulnerability tend to experience tax revenue losses and engage in more borrowing after a PDD, whereas higher-income counties see increased tax revenues and spending and also receive more intergovernmental transfers than their poorer counterparts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

Parts of the data collected for conducting the current study are not publicly available due to purchase, but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Notes

The PDD allows federal aid to be distributed through various disaster programs to state and local governments, and at times, affected households and businesses as well. The vast majority of federal disaster aid is provided after a PDD. It is estimated that from 2005 to 2019, the federal government spent over $460 billion on disaster assistance (Pew 2020), and about $200 billion was disbursed through the Disaster Relief Fund (DRF), the primary source of federal disaster relief aid administered by FEMA (Congressional Research Service or CRS 2020).

For example, Strobl (2011) finds that hurricanes cause the out-migration of higher-income households and such disaster-induced relocation and demographic changes can negatively affect local own-source revenues.

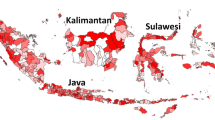

Connecticut and Rhode Island are excluded due to data unavailability.

It should be noted that the differences are not only statistically significant but also economically significant. Specifically, the county-level average personal income per capita in our sample is about 20% higher than that of the non-sampled counties. The average county population in our sample is more than six times bigger than that of the non-sampled counties. The total population from the counties in our estimation sample accounted for approximately 85% of the entire U.S. population in 2015.

If the measurement error is random, it should not bias our estimates of disaster-induced fiscal impacts but may cause more noise. Yet, it is possible that governments may engage in “strategic reporting” of their financial data, which could occur in both directions. If the pattern of strategic reporting is associated with certain county characteristics, this may cause more systematic measurement errors and potentially bias our estimates. In our empirical model, we include the county fixed effects to alleviate the self-reporting bias.

We also performed the T-test between our sampled counties and non-sampled counties in the four fiscal measures and found the two groups are relatively comparable. There is no statistical difference in their average tax revenues and long-term debt per capita. Our sampled counties have higher public spending and intergovernmental revenues than those not included, but their differences are only marginally significant (at the 10% level).

We specify and estimate the dynamics in relative periods from t-9 to t + 9 in the regression to allow for examining a 10-year cumulative effect since the PDD shock occurs in year t. In addition, the model includes an indicator for all years prior to this period and one for all years after. We do not report the coefficients on this pair of indicators as they are less meaningful to interpret.

While hurricanes induce larger long-term increases in intergovernmental transfers and long-term debt issuance than flooding, they also cause larger tax revenue losses than flooding, which may constrain local spending growths.

In our national sample of counties, the total tax revenue variable highly correlates with property tax revenues (correlation coefficient is 0.96), and the latter on average accounts for 77% of the former.

We also estimated the impact of PDDs on a county’s population size using data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis and do not find a significant disaster effect. In addition to property taxes, we have also examined the changes in a county’s total sales tax revenues following PDDs. Our results, available upon request, suggest that flooding and hurricane PDDs generally have insignificant effects on sales tax revenues in the short- or longer term.

References

Albala-Bertrand JM (1993) Political economy of large natural disasters. Clarendon Press, Oxford

Atreya A, Ferreira S (2015) Seeing is believing? Evidence from property prices in inundated areas. Risk Anal 35(5):828–848

Baade RA, Baumann R, Matheson V (2007) Estimating the economic impact of natural and social disasters, with an application to Hurricane Katrina. Urban Stud 44(11):2061–2076

Benson C, Clay EJ (2004) Understanding the economic and financial impacts of natural disasters, vol 4. World Bank, Washington, DC

Billings SB, Gallagher E, Ricketts L (2019) Let the rich be flooded: The distribution of financial aid and distress after Hurricane Harvey. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3396611

Borusyak K, Jaravel X (2018) Revisiting event study designs. Working paper. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2826228

Botzen WJ, Wouter., Deschenes O, Sanders M (2019) The economic impacts of natural disasters: A review of models and empirical studies. Rev Environ Econ Policy 13(2):167–188

Boustan LP, Kahn ME, Rhode PW (2012) Moving to higher ground: Migration response to natural disasters in the early twentieth century. Am Econ Rev 102(3):238–244

Boustan LP, Kahn ME, Rhode PW, Yanguas ML (2020) The effect of natural disasters on economic activity in US counties: A century of data. J Urban Econ 118(103257):0094–1190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jue.2020.103257

Callaway B, Sant’Anna PHC (2021) Difference-in-differences with multiple time periods. J Econ 225(2):200–230

Cassidy CA, Salsberg B (2017) Costs from major natural disasters can stress state budgets. Associated Press, New York

Chen G (2020) Assessing the financial impact of natural disasters on local governments. Public Budg Finance 40(1):22–44

Congressional Research Service (2020) The disaster relief fund: overview and issue. Congressional Research Service R45484. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R45484/20. Accessed Feb 2021

Cuaresma JC, Hlouskova J, Obersteiner M (2008) Natural disasters as creative destruction? Evidence from developing countries. Econ Inq 46(2):214–226

Cutter SL, Boruff BJ, Shirley WL (2003) Social vulnerability to environmental hazards. Soc Sci Q 84:242–261

Davlasheridze M, Vanden F, Allen Klaiber H (2017) The effects of adaptation measures on hurricane induced property losses: Which FEMA investments have the highest returns? J Environ Econ Manag 81:93–114

de Chaisemartin C, D’Haultfoeuille X (2020) Two-way fixed effects estimators with heterogeneous treatment effects. Am Econ Rev 110(9):2964–2996

Dell M, Jones BF, Olken BA (2014) What do we learn from the weather? The new climate-economy literature. J Econ Lit 52(3):740–798

Deryugina T (2017) The fiscal cost of hurricanes: Disaster aid versus social insurance. Am Econ J: Econ Policy 9(3):168–198

Deryugina T, Kawano L, Levitt S (2018) The economic impact of Hurricane Katrina on its victims: evidence from individual tax returns. Am Econ J: Appl Econ 10(2):202–233

Domingue SJ, Emrich CT (2019) Social vulnerability and procedural equity: Exploring the distribution of disaster aid across counties in the United States. Am Rev Public Adm 49:897–913. https://doi.org/10.1177/0275074019856122

Drakes O, Tate E, Rainey J, Brody S (2021) Social vulnerability and short-term disaster assistance in the United States. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 53:2212–4209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.102010

Fannin JM, Barreca JD, Detre JD (2012) The role of public wealth in recovery and resiliency to natural disasters in rural communities. Am J Agric Econ 94(2):549–555

Gallagher J (2014) Learning about an infrequent event: evidence from flood insurance take-up in the United States. Am Econ J: Appl Econ 6(3):206–233

Gallagher J, Hartley D (2017) Household finance after a natural disaster: The case of Hurricane Katrina. Am Econ J: Econ Policy 9(3):199–228

Garrett TA, Sobel RS (2003) The political economy of FEMA disaster payments. Econ Inq 41(3):496–509

Hallstrom DG, Smith VK (2005) Market responses to hurricanes. J Environ Econ Manage 50(3):541–561. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeem.2005.05.002

Howell J, Elliott JR (2019) Damage done: The longitudinal impact of natural hazards on wealth polarization in the US. Soc Probl 66(3):448–467. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spy016

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) (2012) Managing the risks of extreme events and disasters to advance climate change adaptation (Special report of working groups I and II of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change). Retrieved from http://ipcc-wg2.gov/SREX/images/uploads/SREX-All_FINAL.pdf. Accessed May 2013

Jerch R, Kahn ME, Lin G(2021) Local public finance dynamics and hurricane shocks NBER Working Paper No. 28050. http://www.nber.org/papers/w28050. Accessed Jan 2022

Kahn M (2005) The death toll from natural disasters: The role of income, geography and institutions. Rev Econ Stat 87(2):271–284

Kousky C (2010) Learning from extreme events: Risk perceptions after the flood. Land Econ 86(3):395–422

Kousky C (2014) Informing climate adaptation: A review of the economic costs of natural disasters. Energy Econ 46:576–592

Liao Y, Kousky C(2021) The fiscal impacts of wildfires on California municipalities, J Assoc Environ Resour Econ, forthcoming. https://doi.org/10.1086/717492

Lis EM, Nickel C (2010) The impact of extreme weather events on budget balances. Int Tax Public Finance 17(4):378–399

Mahul O, Signer B (2014) Financial protection against natural disasters: From products to comprehensive strategies. World Bank, Washington, DC

McGuire M, Silvia C (2010) The effect of problem severity, managerial and organizational capacity, and agency structure on intergovernmental collaboration: Evidence from local emergency management. Public Adm Rev 70(2):279–288

Melecky M, Raddatz C (2011) How do governments respond after catastrophes? Natural-disaster shocks and the fiscal stance. The World Bank

Melecky M, Raddatz C (2014) Fiscal responses after catastrophes and the enabling role of financial development. The World Bank Economic Review

Miao Q (2018) The fiscal implications of managing natural disasters for national and subnational governments. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Natural Hazard Science. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199389407.013.194

Miao Q, Hou Y, Abrigo M (2018) Measuring the fiscal shocks of natural disasters: a panel study of the U.S. States. National Tax Journal 71(1):11–44

Miao Q, Chen C, Lu Y, Abrigo M (2020) Natural disasters and financial implications for subnational governments: Evidence from China. Public Financ Rev 48(1):72–101

Miao Q, Shi Y, Davlasheridze M (2021) Fiscal decentralization and natural disaster mitigation: Evidence from the United States. Public Budg Financ 41(1):26–50

Noy I, Nualsri A (2011) Fiscal storms: public spending and revenues in the aftermath of natural disasters. Environ Dev Econ 16(1):113–128

Ouattara B, Strobl E (2013) The fiscal implications of hurricane strikes in the Caribbean. Ecol Econ 85:105–115

Ouattara B, Strobl E (2014) Hurricane strikes and local migration in US coastal counties. Econ Lett 124(1):17–20

Painter M (2020) An inconvenient cost: the effects of climate change on municipal bonds. J Financ Econ 135:468–482

Peacock WG, Van Zandt S, Zhang Y, Wesley E, Highfield (2014) Inequities in long-term housing recovery after disasters. J Am Plann Association 80(4):356–371

Pew (2020) How states pay for natural disasters in an era of rising costs – A nationwide assessment of budgeting strategies and practices. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/reports/2020/05/how-states-pay-for-natural-disasters-in-an-era-of-rising-costs. Accessed Jan 2021

Salkowe RS, Chakraborty J (2009) Federal disaster relief in the US: The role of political partisanship and preference in presidential disaster declarations and turndowns. J Homel Secur Emerg Manag 6(1): Article 28,1–21

Shi L, Varuzzo AM (2020) Surging seas, rising fiscal stress: Exploring municipal fiscal vulnerability to climate change. Cities 100:102658

Skidmore M, Toya H (2002) Do natural disasters promote long-run growth? Econ Inq 40(4):664–687

Strobl E (2011) The economic growth impact of hurricanes: Evidence from US coastal counties. Rev Econ Stat 93(2):575–589

Sun L, Abraham S (2021) Estimating dynamic treatment effects in event studies with heterogeneous treatment effects. J Econ 225(2):175–199

Unterberger C (2018) How flood damages to public infrastructure affect municipal budget indicators. Econ Disasters Clim Change 2:5–20

U.S. Government Accountability Office (2012) Federal Disaster Assistance: Improved criteria needed to assess a jurisdiction’s capability to respond and recover on its own. GA0-12-838, Washington, DC. http://www.gao.gov/assets/650/648162.pdf

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Qing Miao conducted the literature review, data analysis and wrote the main manuscript text. Michael Abrigo worked on the econometric modeling. Yilin Hou and Yanjun Liao contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Competing Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 578 KB)

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Miao, Q., Abrigo, M., Hou, Y. et al. Extreme Weather Events and Local Fiscal Responses: Evidence from U.S. Counties. EconDisCliCha 7, 93–115 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-022-00120-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-022-00120-y