Abstract

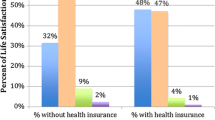

We examine the impact of life and health insurance spending on subjective well-being. Taking advantage of insurance spending and subjective well-being data on more than 700,000 individuals in Japan, we examine whether insurance spending can buffer declines in subjective well-being due to exposure to mass disaster. We find that insurance spending can buffer drops in subjective well-being by approximately 3–6% among those who experienced the mass disaster of the great East Japan earthquake. Subjective health increases the most, followed by life satisfaction and happiness. On the other hand, insurance spending decreases the subjective well-being of those who did not experience the earthquake by approximately 3–7%. We conclude by monetizing the subjective well-being loss and calculating the extent to which insurance spending can compensate for it. The monetary value of subjective well-being buffered through insurance spending is approximately 33,128 USD for happiness, 33,287 USD for life satisfaction, and 19,597 USD for subjective health for a person in one year. Therefore, we confirm that life/health insurance serves as an ideal option for disaster adaptation. Our findings indicate the importance of considering subjective well-being, which is often neglected when assessing disaster losses.

Similar content being viewed by others

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Code Availability

The codes generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

Earthquake insurance is bundled with fire insurance. To be precise, having fire insurance is necessary in order to have earthquake insurance. Fire insurance policyholders who do not have earthquake insurance may incorporate it at any point during the policy duration.

Separating the subscription fee and annual premium in the model may be possible and interesting from the viewpoint of behavioral economics. However, in other fields, it is common to treat all price-related variables together, as consumers are believed to be rational enough to care only about the final prices that they must pay. Therefore, we use subscription fees and annual premiums together in our empirical analysis.

Since we match the data by geographic and socioeconomic features, not at the individual level, there is no guarantee that the same individuals are counted in the two data sources. However, our merged dataset shows correlations between the first and the second datasets; for example, the first dataset's income and age levels were correlated at rates of 99.21% and 94.13%, respectively, with those in the second dataset. The reason why the correlation is not 100% is because we merge the two datasets based on the range (income and age) rather than the precise number. Therefore, there are slight differences in these variables if we look closer.

Group 1 and Group 2 are mutually exclusive.

Proportions that range from 3.86% to 7.50% show the same estimated coefficients; therefore, our results focusing on the 7.50% proportion show the upper bound of the relationship between insurance spending and SWB.

References

Almond D, Edlund L, Palme M (2007) Chernobyl’s subclinical legacy: prenatal exposure to radioactive fallout and school outcomes in Sweden. https://doi.org/10.3386/w13347

Arai Y, Ikegami N (1998) Health care systems in transition II. Japan, Part I. an overview of the japanese health care systems. J Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.pubmed.a024713

Arampatzi E, Burger M, Stavropoulos S et al (2020) The role of positive expectations for resilience to adverse events: subjective well-being before, during and after the greek bailout referendum. J Happiness Stud 21:965–995. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00115-9

Berger EM (2010) The chernobyl disaster, concern about the environment, and life satisfaction. Kyklos. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6435.2010.00457.x

Berlemann M (2016) Does hurricane risk affect individual well-being? empirical evidence on the indirect effects of natural disasters. Ecol Econ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2016.01.020

Cameron L, Shah M (2015) Risk-taking behavior in the wake of natural disasters. J Hum Resour 50(2):484–515

Cameron AC, Trivedi PK, Milne F, Piggott J (1988) A microeconometric model of the demand for health care and health insurance in Australia. Rev Econ Stud 55(1):85–106

Carter MR, Little PD, Mogues T, Negatu W (2007) Poverty traps and natural disasters in Ethiopia and Honduras. World Dev. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2006.09.010

Carvalho, Vasco M, Nirei M, Saito YU, Tahbaz-Salehi A (2020) Supply chain disruptions: evidence from the great East Japan earthquake*. Q J Econo December. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjaa044

Cohen GH et al (2019) Improved social services and the burden of post-traumatic stress disorder among economically vulnerable people after a natural disaster: a modelling study. Lancet Planetary Health 3(2):e93-101

Cummins RA (2000) Personal Income and Subjective Well-being: A Review. J Happiness Stud 1:133–158. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010079728426

Currie J, Decker Sandra, Lin Wanchuan (2008) Has public health insurance for older children reduced disparities in access to care and health outcomes? J Health Econ 27(6):1567–1581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2008.07.002 (ISSN 0167-6296)

Diener E, Biswas-Diener R (2002) Will money increase subjective well-being? Soc Indic Res 57:119–169. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1014411319119

Filipski M, Jin L, Zhang X, Chen KZ (2019) Living like there’s no tomorrow: the psychological effects of an earthquake on savings and spending behavior. Eur Econ Rev 116:107–128

Fortson JG (2011) Mortality risk and human capital investment: the impact of HIV/AIDS in Sub-Saharan Africa. Rev Econ Stat. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_00067

Frey BS, Luechinger S, Stutzer A (2009) the life satisfaction approach to valuing public goods: the case of terrorism. Public Choice. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-008-9361-3

Frey BS, Luechinger S, Stutzer A (2010) the life satisfaction approach to environmental valuation. Ann Rev Resour Econ. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.resource.012809.103926

Frijters P, Johnston DW, Shields MA (2011) Life satisfaction dynamics with quarterly life event data*. Scand J Econ. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9442.2010.01638.x

Gao M, Liu Y-J, Shi Y (2020) Do People feel less at risk? Evidence from disaster experience. J Financ Econ 138(3):866–888

Higa K, Nonaka R, Tsurumi T, Managi S (2019) Migration and human capital: evidence from Japan. J Jpn Int Econ 54(December):101051

Hikichi H, Sawada Y, Tsuboya T, Aida J, Kondo K, Koyama S, Kawachi I (2017) Residential relocation and change in social capital: A natural experiment from the 2011 Great East Japan earthquake and tsunami. Sci Adv 3(7):e1700426. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.1700426

Hudson P, Botzen WJW, Czajkowski J, Kreibich H (2017) Moral hazard in natural disaster insurance markets: Empirical evidence from Germany and the United States. Land Econ 93(2):179–208

Hudson P, Pham My, Bubeck P (2019a) An evaluation and monetary assessment of the impact of flooding on subjective well-being across genders in Vietnam. Climate Dev. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2019.1579698

Hudson P, Wouter Botzen WJ, Poussin J, Aerts JCJ (2019b) Impacts of flooding and flood preparedness on subjective well-being: a monetisation of the tangible and intangible impacts. J Happiness Stud. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-017-9916-4

Kahneman D, Deaton A (2010) High income improves evaluation of life but not emotional well-being. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107(38):16489–16493. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1011492107

Kahneman D, Tversky A (1979) Prospect theory: An analysis of decisions under risk. Econometrica 47:278

Keng S-H, Wu S-Y (2013) Living happily ever after? The effect of Taiwan’s National Health Insurance on the happiness of the elderly. J Happiness Stud 15(4):783–808. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9449-4

Koijen R, Van Nieuwerburgh S, Yogo M (2011) Health and mortality delta: assessing the welfare cost of household insurance choice. https://doi.org/10.3386/w17325

Lamond JE, Joseph RD, Proverbs DG (2015) An exploration of factors affecting the long term psychological impact and deterioration of mental healths in flooded households. Environ Res. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2015.04.008

Luechinger S (2009) Valuing air quality using the life satisfaction approach. Econ J. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2008.02241.x

Luechinger S, Raschky PA (2009) Valuing flood disasters using the life satisfaction approach. J Public Econ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2008.10.003

Markhvida M, Walsh B, Hallegatte S, Baker J (2020) Quantification of disaster impacts through household well-being losses. Nat Sustain. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-020-0508-7

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC) (2013) 2010 Population Census. https://www.stat.go.jp/data/kokusei/2010/

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC) (2015) 2015 Survey of Household Economy. https://www.stat.go.jp/data/joukyou/index.html

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC) (2017) 2015 Population Census. https://www.stat.go.jp/data/kokusei/2015/kekka.html

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC) (2019a) 2019 Population Estimates. http://www.stat.go.jp/data/jinsui/index.html

Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications (MIC) (2019b) 2019 February Labour Force Survey. https://www.stat.go.jp/data/roudou/index.html

Moriyama N, Omata J, Sato R, Okazaki K, Yasumura S (2020) Effectiveness of group exercise intervention on subjective well-being and health-related quality of life of older residents in restoration public housing after the great East Japan earthquake: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 46:2212–4209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101630 (ISSN 2212-4209)

Ohtake F, Yamada K, Yamane S (2016) Appraising unhappiness in the wake of the Great East Japan earthquake. Jpn Econ Rev. https://doi.org/10.1111/jere.12099

Oishi S, Kimura R, Hayashi H, Tatsuki S, Tamura K, Ishii K, Tucker J (2015) Psychological adaptation to the Great Hanshin-Awaji earthquake of 1995: 16 years Later victims still report lower levels of subjective well-being. J Res Pers. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2015.02.001

Okuyama N, Inaba Y (2017) Influence of natural disasters on social engagement and post-disaster well-being: the case of the Great East Japan earthquake. Japan World Econ 44:1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japwor.2017.10.001 (ISSN 0922-1425)

Oswald AJ, Powdthavee N (2007) Death, happiness, and the calculation of compensatory damages. Law and Happiness. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226676029.003.0009

Oswald AJ, Powdthavee N (2008) Does happiness adapt? A longitudinal study of disability with implications for economists and judges. J Public Econ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2008.01.002

Qing C, Guo S, Deng X, Xu D (2021) Farmers’ disaster preparedness and quality of life in earthquake-prone areas: the mediating role of risk perception. Int J Disaster Risk Reduct 59:102252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102252

Rehdanz K, Welsch H, Narita D (2015) Toshihiro Okubo “well-being effects of a major natural disaster: the case of Fukushima.” J Econ Behav Organ 116(August):500–517

Shi Y, Joyce C, Wall R, Orpana H, Bancej C (2019) a life satisfaction approach to valuing the impact of health behaviours on subjective well-being. BMC Public Health 19(1):1547

Sibley CG, Bulbulia J (2012) Faith after an earthquake: a longitudinal study of religion and perceived health before and after the 2011 Christchurch New Zealand earthquake. PLoS One 7(12):e49648

Sugano S (2016) The well-being of elderly survivors after natural disasters: measuring the impact of the Great East Japan earthquake. Jpn Econ Rev 67(2):211–229. https://doi.org/10.1111/jere.12103

Thaler RH, Tversky A, Kahneman D, Schwartz A (1997) The effect of myopia and loss aversion on risk taking: an experimental test. Q J Econ 112(2):647–661. https://doi.org/10.1162/003355397555226

Tran NLT, Wassmer RW, Lascher EL (2017) The health insurance and life satisfaction connection. J Happiness Stud 18(2):409–426

Tsurumi T et al (2021) Are cognitive, affective, and eudaimonic dimensions of subjective well-being differently related to consumption? Evidence from Japan. J Happiness Stud 22(6):2499–2522. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-020-00327-4

Tsurumi T, Managi S (2015) Environmental value of green spaces in Japan: An application of the life satisfaction approach. Ecol Econ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.09.023

Valenti M, Masedu F, Mazza M, Tiberti S, Di Giovanni C, Calvarese A, Pirro R, Sconci V (2013) A longitudinal study of quality of life of earthquake survivors in L’Aquila, Italy. BMC Public Health. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1143

von Möllendorff C, von Möllendorff C, Hirschfeld J (2016) Measuring impacts of extreme weather events using the life satisfaction approach. Ecol Econ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2015.11.013

Welsch H (2006) Environment and happiness: valuation of air pollution using life satisfaction data. Ecol Econ. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2005.09.006

Yule W, Bolton D, Udwin O, Boyle S, O’Ryan D, Nurrish J (2000) The long-term psychological effects of a disaster experienced in adolescence: I: the incidence and course of PTSD. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00635

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the financial supports from Specially Promoted Research through a Grant-in-Aid (20H00648) from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) and the Environment Research and Technology Development Fund (JPMEERF20201001) from the Japanese Ministry of the Environment. The Life-insurance data is provided by Dai-Ichi Life Insurance Company.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of Interest/Competing Interests

The authors declare they have no financial interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Table 7 shows a distribution of the socio-economic variables of our sample and government statistics.

Because SWB variables are categorical variables, it is possible to run a regression using ordered logit analysis. Thus, we conduct an additional robustness check by running our main regression model written in Eq. (1) based on ordered logit regression. Table 8 presents our results, and we do not find qualitatively different results from the main result in Table 3; thus, we confirm that our main results in Table 3 are robust.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Yoo, S., Kumagai, J., Kawabata, Y. et al. Insuring Well-Being: Psychological Adaptation to Disasters. EconDisCliCha 6, 471–494 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-022-00114-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41885-022-00114-w