Abstract

This paper bypasses the mathematical technicalities of baroclinic instability and tries to provide a more conceptual, mechanistic explanation for a phenomenon that is fundamentally important to the dynamics of the earth’s atmosphere and oceans. The standard conceptual picture of baroclinic instability is reviewed and stripped down to identify the most essential features. These are: (a) Regions with both positive and negative potential vorticity (PV) gradients, (b) separate Rossby wave perturbations in each region where PV gradients are of different signs, and (c) cooperative phase locking between Rossby waves in regions of opposite PV gradient, which renders them stationary, and allows them to amplify to reduce the background temperature gradient (or baroclinicity) while still conserving total PV. These three factors constitute the “counterpropagating Rossby wave” perspective, and suggest the heuristic picture of a “PV seesaw”, which remains balanced as the instabilities (i.e., the phase-locked PV wave perturbations) grow out along opposite limbs. After reviewing the key characteristics of PV and Rossby waves, the process is illustrated by the spontaneous onset of baroclinic instability during spin-up of the Held–Suarez dynamical core atmospheric model.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Since the earth is both differentially heated and rapidly rotating, there is a tension between the thermodynamic imperative to reduce the meridional temperature gradient, and the dynamic inhibition against displacing fluid meridionally—at least outside the tropics. Poleward heat transport by mean meridional circulations is not a viable option poleward of 30° or so (see e.g., Held and Hou 1980; Held 2000; and Frierson et al. 2007). The mechanism that resolves this tension is that of baroclinic instability.

It is relatively easy to explain how convective instability works, because the model of individual “parcels” moving buoyantly in one dimension is perfectly adequate. However, trying to explain baroclinic instability is trickier because, as outlined below and in standard textbooks like Holton (2004), the parcel concept is inadequate by itself and really should be supplemented with that of a wave, or a vortex tube. The relevant waves are Rossby waves, which only occur in the context of flows that have non-uniform potential vorticity (PV). So both PV and Rossby waves require explanations of their own if baroclinic instability is to be properly understood. Moreover, baroclinic instability is fundamentally a three-dimensional process.

Most large-scale mid-latitude weather systems and oceanic mesoscale eddies originate from some form of baroclinic instability. It is the process that generates the main features of interest on synoptic weather charts. This paper attempts to bypass the mathematical technicalities of baroclinic instability and provide a more conceptual, mechanistic explanation for an important phenomenon in the dynamics of the earth’s atmosphere and oceans. Perhaps trying to explain baroclinic instability without using mathematics is like describing a spiral staircase without using your hands: it is just not natural. But baroclinic instability is a physical process acting under relatively well-understood physical constraints, so the mathematical details need not be essential to our understanding, and an exercise like this should thus be worthwhile. Persson (1998) and Phillips (2000) took a similar approach in exploring the Coriolis force, and many of the processes and constraints explained in those articles are relevant here too.

2 Mathematical History

Our theoretical understanding of baroclinic instability derives mainly from idealized mathematical models, such as those of Eady (1949) and Charney (1947), or discretized layer models—especially the two-layer model (Phillips 1954; Pedlosky 1979). In those models, a necessary condition for baroclinic instability to occur is that the background potential vorticity gradient (∇Q) change sign somewhere in the domain. Indeed, this is a robust and general condition, known from its mathematical derivation as the Charney–Stern–Pedlosky theorem (Charney and Stern 1962; Pierrehumbert and Swanson 1995). As this paper tries to show, it may be understood from a purely physical perspective as well. If it is not satisfied, small disturbances that “tilt against the shear” may still grow transiently for a while as they are “stood up” by the shear (the “Orr effect”: Orr, 1907, Farrell 1982, Farrell 1984), but as time goes on the shear tilts them over in the opposite sense, and they ultimately decay without significantly changing the original flow.

The standard approach to the Eady, Charney and multi-layer models mentioned above, is to linearize the governing equations about a relatively simple basic state flow, and look for normal mode solutions. Normal modes are typically waves with fixed horizontal wavelengths, and vertical structures that are eigenfunctions of the system. All normal modes preserve their fixed shape as they grow, decay, or just propagate, over time. Normal mode solutions typically involve the appearance of “critical layers”, where the phase speed of the wave equals the speed of the background flow, and careful mathematics are sometimes needed to avoid the singularities associated with them. Some theories of baroclinic instability invoke the concept of over-reflection at critical layers (Lindzen and Tung 1978; Lindzen 1988). Farrell (1984) and O’Brien (1992) describe more general non-modal baroclinic wave solutions that can change their shape over time. Such flexibility allows some of these waves to grow faster than normal modes—or even grow temporarily where normal modes cannot grow at all.

The Eady, Charney, and multi-layer model solutions to the quasigeostrophic potential vorticity equation all provide key insights into the mechanism of baroclinic instability. Along with the requirement that the basic state PV gradient change sign somewhere within the domain, these models illustrate how solutions consisting of pairs of neutral Rossby waves propagating in opposite directions can connect and become phase locked as they evolve into two stationary waves, one growing over time, the other decaying. The growing waves, i.e., the unstable ones, have characteristic geopotential structures that tilt with height to “lean against” the basic state shear, and have wind and temperature fields that are out of phase so that warm air is advected poleward and cold air advected equatorward, leading to net poleward heat transport, which is the real thermodynamic function of such waves. As baroclinically unstable waves grow to finite size, they tap into the available potential energy stored in the baroclinicity of the background flow, converting it into kinetic energy of the wave itself, and thereby reducing the overall “baroclinicity” of the flow. A cascade of energy conversions may transfer energy into other waves or ultimately back into the zonal flow—but a zonal flow that has been modified by the instability, with overall less baroclinicity, less vertical shear and a weaker meridional temperature gradient than the original one.

All these insights may be gleaned even from simple quasigeostrophic two-layer beta-plane models. They are well presented in standard textbooks (e.g., Holton 2004; Pedlosky 1979; Vallis 2006), and in comprehensive reviews such as Pierrehumbert and Swanson (1995). Essentially the same processes, but in more realistic earth-like settings, occur in the baroclinic wave “life cycle” experiments of Simmons and Hoskins (1978), or Jablonowski and Williamson (2006), using the full nonlinear equations of motion on a rotating sphere.

Insofar as this paper tries to distil and explain the essential physics of baroclinic instability, it is not necessary to invoke normal modes or indeed any explicitly linear theory at all. There is no need to consider critical levels, or over-reflection, or find solutions to partial differential equations. The two main challenges that must be met to reach a satisfying intuitive understanding of baroclinic instability are: an appreciation of potential vorticity (and its conservation), and of Rossby waves. In the terminology of Harnik and Heifetz (2007), the perspective here is essentially that of the “counterpropagating Rossby waves”, in contrast to over-reflection—although their paper goes a long way to unifying the two. Hoskins et al. (1985) presented a very clear exposition of baroclinic instability in terms of counterpropagating Rossby waves and in many ways this article is a synopsis of their one, albeit from a slightly different perspective.

3 The Context: Differential Heating on a Rotating Sphere

Differential heating by the sun builds up large meridional temperature gradients between the tropics and the poles on the earth’s surface and in the atmosphere. Mean meridional circulations (e.g., the Hadley cell) arise in response to these, and try to reduce them. If the earth did not rotate, there would be nothing to stop colder, denser air at high latitudes from slipping downwards and equatorward under gravity, with warm air aloft moving poleward to preserve mass continuity, in a single hemisphere-spanning circulation cell. This is essentially what happens in baroclinic situations where the earth’s rotation is immaterial, such as sea-breeze circulations.

At another extreme, if there were no meridional temperature gradient at all, the earth’s rotation and sphericity would still establish meridional pressure gradients in balance with the centrifugal force. Perturbations of this balance would generate either inertial waves or Rossby waves, both of which consist of air parcels oscillating about their base latitude. Inertial waves arise from the interplay between equatorward centrifugal force and poleward gravitational force on an ellipsoidal earth (Phillips 2000). Rossby waves arise in a context where absolute (or potential) vorticity is conserved even as planetary vorticity changes with latitude. Parcels (or vortex tubes) perturbed from their base latitude must then develop either positive or negative relative vorticity so that the absolute vorticity conservation constraint is satisfied. In either case, as the planet rotates faster, the restoring forces in the waves become stronger, and meridional displacements of fluid parcels from their base latitudes are restricted to an ever narrower range.

The earth’s rotation and sphericity means that the upper branch of the Hadley cell acquires an increasing westerly velocity (by conservation of angular momentum) as it moves poleward and closer to the axis of rotation. By 30° latitude or so, that westerly velocity (and associated vertical shear), now essentially the subtropical jet, is large enough to make poleward heat transport by the mean meridional circulation relatively inefficient. At a certain point (as explained below), the subtropical jet breaks down into a series of baroclinically unstable waves, which provide a more efficient alternative means of transporting heat poleward and reducing the meridional temperature gradients. Figure 1 shows a highly simplified schematic of this process. Levine and Schneider (2015) explore the relationship between the Hadley circulation and baroclinic instabilities quite thoroughly. The efficiency of baroclinic heat transport, the turbulence of the unstable waves, and how all those processes might be parameterized are subjects of quite a large literature. The focus here is just on the onset of baroclinic instability and the conditions that trigger it.

Schematic of mean meridional circulation cells, in the case of (a) slow rotation or none at all, where the Hadley cell extends almost to the poles, and (b) fast rotation, as on the earth, where the Hadley cell generates a strong subtropical jet at its high-latitude limit. As the jet exceeds a threshold speed (or vertical shear), it breaks down into unstable baroclinic waves. In (b), the upper branch of the Hadley cell acquires a strong westerly component, shown by the wind vectors exiting to the east and re-entering from the west

4 The Baroclinic Wedge of Instability

Figure 2 shows a standard view of the “wedge of instability”, which is a staple of dynamics textbooks (Pedlosky 1979; Vallis 2006). Heifetz et al. (1998) explored this in detail in the context of the Eady model. See also Thorpe et al. (1989). A situation where density (or isentropic) surfaces are not parallel to isobaric surfaces (as in Fig. 2) is what makes a fluid baroclinic, and amounts to a definition of baroclinicity. The angle between the isentropes and isobars is proportional to the available potential energy (APE) built up in the fluid, at least some of which is tapped by any baroclinic instability and converted to kinetic energy of the growing waves. Note that the flow in Fig. 2 is hydrostatically stable, so parcels perturbed directly upwards will be denser than their environment and so sink back down, while parcels perturbed directly downwards will be less dense than their environment and so rise back up—returning to their original position in either case (as shown by the green arrows).

Schematic of baroclinic or “slant-wise” instability. Parcels of air following the green arrows will tend to return exactly to their origin point, so those perturbations are stable. Parcels following the purple arrows will also tend to return to their original density (or isentropic) surface, but at a different pressure level; those perturbations may be “unstable”, provided other conditions are satisfied

Parcels perturbed along the paths of the purple arrows in Fig. 2, however, will not tend to return to their original position, but rather return vertically to their original isentrope (or density surface) at a different horizontal location. In principle, this is a manifestation of baroclinic instability, and sure enough, as shown by Heifetz et al. (1998), parcel displacements in the Eady model of baroclinic instability do indeed occur at various angles within that unstable wedge between the isentropes and the isobars.

Nevertheless, the model of fluid parcels moving within the baroclinic “wedge of instability” is unsatisfying for at least two reasons. First, the “instability” appears to be very tightly bounded. The description above provides no mechanism for parcels perturbed within the wedge of instability to continue any further north or south than their initial displacement. This instability appears to be nothing more than a limited horizontal perturbation followed by vertical hydrostatic equilibration.

Second, and perhaps more subtly, should any localized perturbation grow to an instability that achieves localized baroclinic adjustment (i.e., pulls the local isentropes and isobars back into parallel), this must inevitably lead to generation of even more baroclinicity in the regions north and south of the adjusted region, as shown schematically in Fig. 3. Local baroclinic adjustment (as in Fig. 3) certainly reduces the overall APE of the original baroclinic state (as measured, e.g., by the total area between the pressure and density curves in Fig. 3 over a finite latitude span), but increases the local APE (or baroclinicity), as measured by the local angle between the adjusted density and adjusted pressure curves. There is nothing unphysical about this: as long as overall APE is reduced, local gradients may be enhanced as part of the process—as happens, e.g., during the formation of cold fronts. Similar effects may be seen in the baroclinic life cycle simulations of Simmons and Hoskins (1978) or Mak et al. (2016). Nevertheless, those are primarily macro-scale effects that occur towards the end of the life cycles of mature baroclinic cyclones. How plausible is it that small, growing instabilities will narrow the wedge of instability in one local region while widening it in neighboring regions? What determines which local regions become stabilized, and which ones destabilized? Once stabilized, can a local region be destabilized again by adjustment of neighboring regions to the north or south? I think those are fair questions, but the standard “wedge of instability” picture (as in Figs. 2 and 3) is really inadequate to answer them.

Part of the answer, which only really becomes clear in the PV context, is that the sloping isentropes or density surfaces become baroclinically unstable much more readily if they curve downwards, as shown by the red “initial density” curve in Fig. 4, instead of being linear (as in Fig. 3) or curving in the opposite sense. Linear profiles that intersect the lower boundary may support instabilities too, but the mathematical formalities that handle the surface discontinuity essentially introduce a local infinitesimal curvature right at the surface (Bretherton 1966; Lindzen and Tung 1978). Vertically discretized models with standard surface boundary conditions all avoid this discontinuity problem quite naturally by virtue of their vertical discretization. Whether the isentropic curvature shown in Fig. 4 is localized at the bottom of the atmosphere just above the surface, or whether it extends deep into the troposphere, such curvature is intimately connected to the necessary conditions for baroclinic instability to occur.

Given the initial baroclinic situation shown in Fig. 4 (i.e., the purple curve), it is easy to see how the “wedge of instability” can be reduced from the surface upwards (following the orange adjusted curve) without requiring the destabilization of any neighboring regions at all (as in Fig. 3b). Baroclinicity and associated APE have been reduced everywhere; there are no counter-gradient artifacts (as in Fig. 3) to complicate matters.

5 Conservation of Potential Vorticity

The easiest way to understand baroclinic instability is to view it from a potential vorticity (or “PV”) perspective, since the essential features of the instability are all determined by the need to conserve PV. The PV conservation constraint is particularly strong in that it holds not just globally, but also in a Lagrangian sense, following any material part of the fluid. Some dramatic examples of conservation of PV are provided by tornados and water spouts. The “potential” vorticity in weak and shallow rotation is converted into strong actual vorticity as the funnel is stretched vertically until it reaches the ground. The vortex itself can move horizontally and undulate like a snake but, due to the conservation of PV, can retain its coherence over very long times (relative to the period of rotation), until friction or other external forces intervene.

Even air with no local motion—i.e., in solid body rotation with the earth—has planetary vorticity as a component of its PV. At scales large enough to sense the earth’s rotation, PV must be conserved as air moves about in the environment of a strong positive meridional planetary vorticity gradient, which is due to the earth’s sphericity. Rossby waves may arise and propagate on that gradient, as discussed below.

Formally, vorticity is the curl of the wind vector. Meteorology is mostly concerned with the local vertical component of vorticity. More informally, vorticity is the rotational or shear component of the horizontal flow at each point, or the propensity of the flow to “turn” at each point. In principle, a vorticity meter is one of the simplest of all meteorological instruments, something like an anemometer, but with flat vertical paddles instead of cups distributed symmetrically about a central axis. If a vorticity meter immersed in a flow was to turn about its axis, the flow has vorticity at that point, either positive or negative, depending on the direction of rotation. Of course, such vorticity meters are too small to be sensitive to synoptic-scale vorticity, and so are of little practical use in meteorology. Nevertheless, some interesting applications of a vorticity meter (along with explanations of vorticity itself), as recorded by Dr. Ascher Shapiro of MIT, in 1961, may be viewed online at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbMUB7usKPQ. When trying to conceptualize vorticity, it can be helpful to imagine how a “virtual vorticity meter” would behave at any given point.

Consider a small parcel of fluid circulating at radius r about a central axis, with angular velocity Ω. Its linear momentum (per unit mass) is rΩ, its angular momentum (per unit mass) is r2Ω, while its vorticity (parallel to the axis of rotation) is 2Ω. Vorticity is a purely local quantity: it makes no reference to any axis of rotation or to distance from it. It can be helpful to think of vorticity as the limit, as a surface area becomes infinitesimally small, of the tangent flow integrated around the edge of the surface (“circulation”), divided by the surface area. Thus, integrating tangential velocity rΩ about a circle centered on the axis of rotation yields 2πr × rΩ. Dividing this by the area of the circle πr2 yields the vorticity 2Ω.

Planetary vorticity exists because of the rotation of the earth, regardless of the reference frame. The planetary vorticity gradient (the “beta-term” in quasigeostrophic vorticity) then arises from the sphericity of the earth. A virtual vorticity meter planted vertically on the surface of the earth would rotate (in the external, inertial frame) along with the earth itself. At the equator, however, the vorticity meter would not turn about its own axis (i.e., the local vertical direction) at all, since it is perpendicular to the earth’s axis there. At progressively higher latitudes, the component of the vorticity meter axis parallel to the earth’s axis increases, the component of its surface projection perpendicular to the earth’s axis increases, and so does planetary vorticity itself (in proportion to sine of latitude). At any latitude, planetary vorticity is twice the earth’s angular rotation rate multiplied by sine of latitude: \( f \, = \, 2\varOmega {\text{ Sin}}\phi \).

Along with the planetary vorticity due to the “solid body” rotation of the atmosphere, atmospheric flow may also have relative vorticity within the local, non-inertial rotating frame—as commonly represented on synoptic weather charts. A virtual vorticity meter, embedded somewhere in a cyclone or anti-cyclone, or at the edge of a jet, would then rotate by virtue of that local flow, along with the planetary component. Absolute vorticity is the sum of planetary and relative vorticity.

The vorticity vector may be viewed as the infinitesimal limit of circulation about a closed loop divided by the area enclosed by the loop, with the vector direction perpendicular to the enclosed surface area. If the surface chosen is one on which a quantity that is conserved following the flow (e.g., potential temperature) is constant, then the circulation about any closed loop on such a surface is also constant. This idea may be extended into a third dimension, parallel to the vorticity direction, by taking the dot product of vorticity with a stratification vector perpendicular to the (isentropic) surface on which the circulation is calculated. This produces a scalar quantity called Ertel’s potential vorticity (Ertel 1942), which is essentially an infinitesimal vortex tube whose top and bottom surfaces are isentropes. Therefore, the PV bounded by them is also conserved following the flow, at least in the absence of heating or other external forces. Symbolically, Ertel’s PV is defined as:

Here ξθ is relative vorticity (on an isentropic surface); f = 2Ω Sinϕ is planetary vorticity at latitude ϕ, g is gravity, and ∂θ/∂p is the vertical potential temperature gradient or stratification. This is generally negative, so the negative sign is used to make this factor positive.

At macro-scales, PV is proportional to the pressure thickness of the layers between constant isentropes. As the tube shortens or contracts, it must broaden out, and the circulation around the perimeter must decrease to compensate; conversely, as the tube stretches, it narrows, and the circulation around the perimeter must speed up to conserve the overall potential vorticity—much as conservation of angular momentum requires spinning ice skaters to spin faster as they pull in their arms. Conservation of PV is related to, but different from, conservation of angular momentum. If anything it is more general, since PV is conserved within any arbitrarily enclosed region, and does not refer to any central axis of rotation.

Note that PV consists of three distinct components: relative vorticity, planetary vorticity, and fluid stratification. In the case of an initial weak and broad zonal flow in the atmosphere, relative vorticity is negligibly small relative to planetary vorticity. Note that planetary vorticity in the northern hemisphere is positive away from the equator, and increases towards the pole. So where the isentropes are relatively flat or just gently sloping, stratification is almost constant, and the meridional PV gradient is dominated by the positive planetary vorticity gradient. This is typically the situation at and below jet-stream level within the troposphere.

Nevertheless, polar regions are typically colder than tropical ones, especially at the surface, so isentropes do slope upwards with latitude, with the largest isentropic slopes near the surface. Over much of the troposphere, the thickness between isentropes decreases towards higher latitudes, or equivalently, the stratification increases. Consequently, the stratification component of PV also contributes to a positive PV gradient over most of the troposphere.

If it is possible for the meridional PV gradient to become negative, where and how is that most likely to occur? The only possibility is for the stratification term to decrease with latitude somewhere. Away from the surface, this would require the thickness between isentropes to increase even as temperatures decrease (towards higher latitudes). Such physically inconsistent situations do not occur.

However, the concept of material potential vorticity tubes mentioned above needs to be modified at the earth’s surface, since that boundary does not generally correspond to an isentropic surface. Think of a PV tube whose lower isentrope is initially coincident with the earth’s surface (as in the schematic diagram on the left side of Fig. 5). As the high-latitude end of the tube is cooled at the surface, and the low-latitude end warmed, the bottom isentrope tilts so that the high-latitude end is raised above the surface, while the low-latitude end sinks somewhere beneath the surface (right diagram of Fig. 5). At the high-latitude end, the stratification is increased (as is PV), while at the low-latitude end, stratification and PV are both decreased. So this process also promotes a positive meridional PV gradient.

Schematic of how heating can lower the isentropic surface (θ) end of a PV tube at the earth surface, formally reducing θ1 to infinitesimal distance δ below the surface; cooling can lift θ1 above the surface. The resulting surface PV is proportional to surface potential temperature rather than its vertical gradient

But we are forgetting the bit of the original tube that got pulled below the surface. That now has “infinite” stratification, since we may conceive of all the isentropes that intersect the earth’s surface to continue horizontally underground with infinitesimally small thicknesses between them. We may formally multiply everything by that infinitesimally small thickness to obtain a physical value for PV at the boundary itself rather than within a layer. In practice there is nothing fishy here: the concept of infinitesimally thin layers of PV just below the surface is just a technical way of relating a perfectly sensible boundary condition to the fluid interior. See Bretherton (1966) or Lindzen and Tung (1978) for formal justification.

In any case, PV in that part of the original tube that is pulled down to the surface completely dominates the remaining part. What discriminates between the various vortex tubes pulled below the surface by differential heating is not their thickness, but their isentropic values, and those values decrease towards higher latitudes. Since PV at the surface is now effectively proportional to fθ, the meridional PV gradient at the surface becomes negative once the meridional temperature gradient is large enough to overcome the planetary vorticity gradient (the “beta effect”). Thus, for broad, smooth, zonal flows in the atmosphere, only at the surface are the PV gradient likely to become negative.

Based on the idealized Eady, Charney, and Phillips models mentioned above, we expect baroclinic instabilities to grow by transporting PV down the gradient, both where that gradient is positive and where it is negative. In the process, total, domain-averaged PV transport is zero, so PV itself is materially conserved, as it is constrained to be. The mechanism that effects such transport is the Rossby wave.

6 Rossby Wave Propagation

While it is often said, following Aristotle, that nature abhors a vacuum, it could be said more generally that nature abhors a gradient, especially in temperature, and, by the second law of thermodynamics, will spontaneously try to reduce it. If the earth did not rotate, but radiation built up a temperature gradient from tropics to poles, a mean meridional circulation could reduce that gradient by simple convection and continuity. If the earth did rotate, but had no meridional temperature gradient, there would be a meridional PV gradient (entirely due to planetary vorticity) but no need for any local fluid motion—only solid body rotation. Any flow perturbation on a scale large enough to sense the earth’s rotation would ultimately take the form of Rossby waves.

In the context of a positive meridional PV gradient (or simply a planetary vorticity gradient), parcels of air that are perturbed poleward acquire increased planetary vorticity just by virtue of the latitude change, and so must develop negative relative vorticity to compensate and conserve total PV. This induces an anticyclonic local perturbation, bringing parcels poleward from the west side, and sending them equatorward on the east side. Similarly, parcels that are displaced equatorward where planetary vorticity is lower must develop positive relative vorticity to conserve PV. This pulls other parcels equatorward on the west side, and pushes them back poleward on the east. These induced circulations are illustrated schematically in Fig. 6 (synthesized from a presentation by Shane Keating of the Univ. of New South Wales, available at https://www.climatescience.org.au/sites/default/files/Baroclinic%20Instability%20Keating%20.pdf). Much the same idea is illustrated by Figs. 17 and 18 of Hoskins et al. (1985). The meridional extent of the fluid displacements in these Rossby waves is limited by the size of the initial displacement. Fluid parcels will not spontaneously go any further, since the horizontal pressure gradient forces acting on the perturbed fluid tend to restore it to its original latitude.

Schematic of how Rossby waves propagating westwards on positive PV gradient (a), and eastwards on a negative PV gradient (b), may become “phase locked”, and cooperate to reinforce PV perturbations of both positive and negative sign (c)—while still conserving total PV. The X- and Y-axis directions represent eastwards and northwards, respectively

7 Baroclinic Instability: Phase Locking of Upper and Lower Waves

The schematic picture shown in Fig. 6 corresponds closely to analytic mathematical solutions for perturbations in simple quasigeostrophic configurations consisting of uniform vertical shear in a background zonal flow (equivalent, via thermal wind, to a meridional temperature gradient) between rigid upper and lower boundaries. Solutions of the form ei(kx + y — ωt) for streamfunction perturbations yield eigenfunctions that provide the vertical wave structures. In the Eady model at least (and in the Phillips models for large wavenumbers), two stable Rossby wave solutions are obtained when the vertical shear is weak: one propagating westward (ω < 0), the other eastward (ω > 0). The westward-propagating wave may be thought of as anchored in the region aloft where the meridional PV gradient is positive, while the eastward-propagating wave is anchored at the surface, or lowest model layer, where the meridional PV gradient is negative. In the Phillips two-layer model, for low wavenumbers and weak shear, the PV gradient is positive in both layers and so both Rossby wave solutions propagate westward.

As the shear increases, however, those freely propagating waves are replaced by solutions that either grow or decay exponentially in place. This change occurs exactly at the point where (as a direct consequence of the increased shear) the PV gradient becomes negative somewhere in the domain. At this point, the upper and lower Rossby waves connect, and become “phase locked” into what is effectively a growing baroclinic instability. As summarized by Hoskins et al. (1985), “the induced velocity field of each Rossby wave keeps the other in step, and makes the other grow.” In the Eady and Phillips models, the shorter, shallower waves remain stable because they cannot achieve this “phase locking”. They are effectively separated, lacking the vertical penetration needed to connect with each other.

All the essential characteristics of baroclinic instability are captured by the natural evolution of stable Rossby waves into a growing stationary wave (along with a decaying partner wave) as illustrated by the analytic solutions to the Eady model and the Phillips two-layer model (and Fig. 6). The baroclinic instabilities that grow in more complex configurations (such as the Charney model, or multi-layered models) are just elaborations of those simple unstable structures.

If the regions of positive and negative PV gradients are not separated by artificially large vertical distances (as in the Eady and 2-layer models), then even short, shallow waves can (and do) become unstable as well. All baroclinically unstable waves have many common features (such as a westward tilt with height), as mentioned in Sect. 2 and well documented elsewhere (e.g., Pierrehumbert and Swanson 1995; Pedlosky 1979; Holton 2004). These features result from the systematic organization of vertical wave structure to reduce the meridional temperature gradient, as represented by the negative PV gradient at the surface, in the context of a positive PV gradient everywhere else, all subject to the constraint that total PV must be conserved. Some structures are more efficiently organized than others—they do not all have to be the fastest-growing normal mode, or even normal modes at all. They may change shape as they grow, and they may be more or less efficient at extracting APE from the background baroclinicity, and in rearranging the overall PV field (Farrell 1982, 1984; O’Brien 1992).

8 Onset of Baroclinic Instability in the Held–Suarez Model

The spin-up phase of the idealized Held–Suarez model (Held and Suarez 1994) provides a good illustration of how the gradual buildup of PV gradients results in the onset of baroclinic instability as soon as a change in sign of the PV gradient appears somewhere in the domain. In practice, that means as soon as the PV gradient at the surface becomes negative, or as soon as the surface meridional temperature gradient becomes large enough to offset the positive contribution to the PV gradient made by planetary vorticity. The Held–Suarez configuration is forced with an idealized meridional and vertical heating profile that is uniform in longitude and symmetric about the equator. The model surface exerts a frictional force on the atmosphere above, but is uniform everywhere, with no topography or land–sea contrasts. Thus, all forcing and boundary conditions are symmetric in longitude and about the equator. The model is initialized with zero flow and uniform temperature everywhere, apart from a small flow perturbation that breaks the zonal symmetry and seeds the eventual instability. Results shown here are from the finite-volume dynamical core of the Saudi-KAU climate model (Almazroui et al. 2017).

During the spin-up phase, the flow remains zonally symmetric (apart from the arbitrary perturbation) while the idealized forcing builds up the meridional and vertical temperature gradients. The meridional PV gradient of this zonally symmetric circulation (i.e., ∂[(ξθ + f) (− g∂θ/∂p)]/∂ϕ] can be plotted at each time step—and indeed may be viewed as a movie, available in the supplementary material. During spin-up, relative vorticity ξθ is essentially zero. The PV gradient is clearly controlled by the (positive) planetary vorticity gradient ∂f/∂ϕ, and by positive contributions from the stratification (− ∂θ/∂p), especially in the stratosphere.

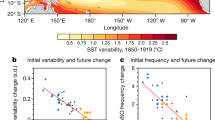

As differential heating builds up the meridional temperature gradient, eventually small regions of negative PV gradient appear at the model surface around 40° latitude, shown as the blue regions in Fig. 7. At this point, the Charney–Stern–Pedlosky condition for instability is satisfied, and given the presence of some perturbation, baroclinic instability occurs immediately. Since the regions with negative PV gradients are initially small and shallow, the baroclinic instabilities are also localized and shallow.

Vertical cross-section of meridional gradient of potential vorticity at longitude = 30°, 53 days into the spin-up from rest of a Held–Suarez model configuration. Quantity shown is the meridional difference in potential vorticity (m2 s−1 K kg−1 × 106) between adjacent grid points approx. 125 km apart. Note the negative gradient in dQ/dy at about 40O latitude, which only appeared first about a day earlier, due to the differential heating in the model. Baroclinically unstable waves, made possible by the change in sign in dQ/dy, quickly grow at these latitudes

Figure 8 shows a longitudinal cross-section at 40° latitude through the perturbation v and θ fields of the growing instability. This is just a random common-or-garden baroclinic wave; it is not a normal mode and was not chosen for any special attributes, other than for being early in its growth phase but still developed enough to reveal its intrinsic features. Indeed, it does show all the features expected in a growing baroclinic wave, including the westward tilt with height of the wind field along with eastward tilt of the temperature field, the out of phase relationship between the wind and temperature fields (for meridional heat advection), and even a hint of the “phase locking” between upper and lower parts of the growing wave. Although the Held–Suarez model is symmetric in its geometry and forcing, it provides a relatively free and unstructured context for the development of baroclinic instabilities, so the snapshot of an early-stage growing baroclinic wave shown in Fig. 8 is quite spontaneous, and is not artificially optimized or idealized in any way. Different initial perturbations lead to different details in the resulting instability, but the overall structures retain all the key common features mentioned above. As the integration of the model proceeds, the forcing builds up even stronger surface temperature gradients, leading to strong and ubiquitous baroclinic instabilities. These eventually grow to feed back nonlinearly on the mean flow, rearrange the mean PV, and ultimately lead to the familiar time- and zonal-mean flow structures of the Held–Suarez model, as are well documented elsewhere (e.g., Wan et al. 2008).

Vertical–longitudinal cross-section snapshot at 40° latitude and same time as Fig. 7, during initial stage of baroclinic instability, showing perturbation potential temperature (θ′, shading, color bar in units of K) and perturbation meridional component of the wind (v′, contours, 2 m s−1 contour interval). Only 180° longitude is shown, since baroclinic instability has not yet occurred (or spread) outside this region

9 Summary: The “PV Seesaw”

While most studies of baroclinic instability (as in references below) take a predominantly mathematical perspective, this paper offers a more heuristic and mechanistic picture. Ultimately, perhaps the clearest insights come from a combination of analytic solutions to the idealized models of Eady and Phillips, and numerical experiments with the Held–Suarez model. Complex as it may be, baroclinic instability nevertheless provides the most efficient way to reduce the large temperature gradients and associated baroclinicity and APE that are generated by differential heating of an atmosphere on a rotating sphere.

While the “parcel model” is useful up to a point, it is ultimately inadequate for a full understanding of baroclinic instability, which is intrinsically three-dimensional, requiring multiple Rossby waves propagating on PV gradients of opposite sign to phase lock so that the wave perturbations may grow down the PV gradient in each region, while conserving PV overall. This suggests the analogy of two bowling balls on opposite limbs of a seesaw, moving away from the center while preserving overall balance.

A variation of this concept is shown schematically in Fig. 9. The regions of positive and negative PV gradients are represented by the gradients of opposite limbs of a seesaw that can pivot independently about a central point (making this a somewhat non-standard seesaw). PV perturbations are represented by the distance that a bowling ball can roll along each limb. The balls are connected to each other by ropes and pulleys, requiring that the distances rolled by each ball must remain in proportion to the other—all reflecting the need to conserve overall PV. Figure 9a represents the situation where only a positive PV gradient [∂Q/∂y > 0] is present. The opposite limb of the seesaw pins the bowling ball representing positive PV perturbations to a solid block, effectively putting a brake on development of PV perturbations of any sign. The brake is then removed by differential heating, which lowers the horizontal limb, allowing both positive and negative PV perturbations to grow as they roll out along opposite limbs (Fig. 9b).

a Schematic of how the PV seesaw restricts unstable growth (i.e., the red ball of negative q′ rolling down the mean Q gradient); the limb with flat Q effectively “clamps” the cable connected to the red ball. b As differential heating takes effect, it reduces the right limb of the seesaw, freeing the cable holding back the red ball (q′ < 0) and thus allowing both red and green balls to roll down their local Q gradients

As the instability grows, the surface temperature gradient is reduced, the “wedge of instability” is narrowed, and eventually the negative PV gradient is eliminated. This process is analogous to raising the right limb of the seesaw in Fig. 9 as the perturbation PV grows along it, to the point where it becomes horizontal and chokes off the instability again. This is a more general nonlinear adjustment than the “barotropic governor” proposed by James (1987), although there certainly may be a barotropic governor element to it. The nonlinear equilibration of baroclinic instability, as manifested in the later, occluded stage of cyclone life cycles, may be seen as the elimination of opposing PV gradients, just as the onset of baroclinic instability depends on their appearance.

References

Almazroui M et al (2017) Saudi-KAU coupled global climate model: description and performance. Earth Syst Environ 1:7. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41748-017-0009-7

Bretherton FP (1966) Critical layer instability in baroclinic flows. Q J R Meteorol Soc 92:325–334. https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.49709239302

Charney JG (1947) The dynamics of long waves in a baroclinic westerly current. J Meteorol 4:135–162. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1947)004%3C0136:TDOLWI%3E2.0.CO;2

Charney JG, Stern M (1962) On the stability of internal baroclinic jets in a rotating atmosphere. J Atmos Sci 19(1):59–72. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1962)019%3C0159:OTSOIB%3E2.0.CO;2

Eady ET (1949) Long waves and cyclone waves. Tellus 1:33–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2153-3490.1949.tb01265.x

Ertel H (1942) Ein neuer hydrodynamischer Wirbesatz. Meteorolol Z 59:271–281

Farrell BF (1982) The initial growth of disturbances in a baroclinic flow. J Atmos Sci 39:1663–1686. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1982)039%3C1663:TIGODI%3E2.0.CO;2

Farrell BF (1984) Modal and non-modal baroclinic waves. J Atmos Sci 41:668–673. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1984)041%3C0668:MANMBW%3E2.0.CO;2

Frierson DMW, Lu J, Chen G (2007) Width of the hadley cell in simple and comprehensive general circulation models. Geophys Res Lett 34:L18804. https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GL031115

Harnik N, Heifetz E (2007) Relating overreflection and wave geometry to the counterpropagating Rossby wave perspective: toward a deeper mechanistic understanding of shear instability. J Atmos Sci 64:2238–2261. https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS3944.1

Heifetz E, Alpert P, da Silva A (1998) On the parcel method and the baroclinic wedge of instability. J Atmos Sci 55:788–795. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1998)055%3C0788:OTPMAT%3E2.0.CO;2

Held IM (2000) The general circulation of the atmosphere, lectures at 2000 Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Program, Woods Hole Mass https://gfd.whoi.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/18/2018/03/lectures2000_21464.pdf

Held IM, Hou AY (1980) Nonlinear axially symmetric circulations in a nearly inviscid atmosphere. J Atmos Sci 37:515–533. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1980)037%3C0515:NASCIA%3E2.0.CO;2a

Held IM, Suarez MJ (1994) A proposal for the intercomparison of the dynamical cores of atmospheric general circulation models. Bull Amer Meteor Soc 75:1825–1830. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1980)037<0515:NASCIA>2.0.CO;2

Holton J (2004) An introduction to dynamic meteorology, 4th edn. Academic Press, San Diego, p 535

Hoskins BJ, McIntyre ME, Robertson AW (1985) On the use and significance of isentropic potential vorticity maps. Q J R Meteorol Soc 111:877–946. https://doi.org/10.1002/qj.49711147002

Jablonowski C, Williamson DL (2006) A baroclinic instability test case for atmospheric model dynamical cores. Q J R Meteorol Soc 132:2943–2975. https://doi.org/10.1256/qj.06.12

James IN (1987) Suppression of Baroclinic Instability in Horizontally Sheared Flows. J Atmos Sci 44:3710–3720. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1987)044%3C3710:SOBIIH%3E2.0.CO;2

Levine XJ, Schneider T (2015) Baroclinic eddies and the extent of the hadley circulation: an idealized GCM study. J Atmos Sci 72:2744–2761. https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-14-0152.1

Lindzen RS (1988) Instability of plane parallel shear-flow (toward a mechanistic picture of how it works). Pure Appl Geophys 126:103–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00876917

Lindzen RS, Tung K-K (1978) Wave overreflection and shear instability. J Atmos Sci 35:1626–1632. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1978)035%3C1626:WOASI%3E2.0.CO;2

Mak M, Lu Y, Deng Y (2016) Upper-level frontogenesis in baroclinic waves. J Atmos Sci 73:2699–2714. https://doi.org/10.1175/JAS-D-15-0250.1

O’Brien EW (1992) Optimal growth rates in the quasigeostrophic initial value problem. J Atmos Sci 49:1557–1570. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1992)049%3c1557:OGRITQ%3e2.0.CO;2

Orr WM (1907) Stability or instability of the steady motions of a perfect liquid. Proc R Irish Acad 27:9–69. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20490591

Pedlosky J (1979) Geophysical Fluid Dynamics. Springer-Verlag, New York, p 624. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4612-4650-3

Persson A (1998) How do we understand the Coriolis force? Bull Amer Meteor Soc 79:1373–1385. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0477(1998)079%3C1373:HDWUTC%3E2.0.CO;2

Phillips NA (1954) Energy transformations and meridional circulations associated with simple baroclinic waves in a two-level, quasi-geostrophic model. Tellus 6:273–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2153-3490.1954.tb01123.x

Phillips NA (2000) An explication of the coriolis effect. Bull Amer Meteor Soc 81:299–303. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0477(2000)081%3C0299:AEOTCE%3E2.3.CO;2

Pierrehumbert RT, Swanson KL (1995) Baroclinic instability. Ann Rev Fluid Mech 27:419–467. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.fl.27.010195.002223

Simmons AJ, Hoskins BJ (1978) The life cycles of some nonlinear baroclinic waves. J Atmos Sci 23:390–400. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1978)035%3C0414:TLCOSN%3E2.0.CO;2

Thorpe AJ, Hoskins BJ, Innocentini V (1989) The parcel method in a baroclinic atmosphere. J Atmos Sci 46:1274–1284. https://doi.org/10.1175/1520-0469(1989)046%3C1274:TPMIAB%3E2.0.CO;2

Vallis GK (2006) Atmospheric and oceanic fluid dynamics. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, p 745. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511790447

Wan H, Giorgetta MA, Bonaventura L (2008) Ensemble Held–Suarez test with a spectral transform model: variability, sensitivity, and convergence. Mon Wea Rev 136:1075–1092. https://doi.org/10.1175/2007MWR2044.1

Acknowledgements

I thank the Center of Excellence for Climate Change Research at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia for their support, and for use of their computing resources.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

As the author, I declare that I have no competing interest.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

O’Brien, E. Balancing the Potential Vorticity Seesaw: The Bare Essentials of Baroclinic Instability. Earth Syst Environ 3, 341–351 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41748-019-00128-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41748-019-00128-7