Abstract

English language proficiency exams are often associated with high-stakes decisions. Guidance however, concerning the writing tasks is often implicit. The emphasis is usually placed upon grammatical and lexical features rather than the pragmatic aspects that differentiate the tasks. Aiming to boost genre awareness as part of L2 pragmatic competence in this context the present paper provides a description of individual exam genres and their relations to each other. Such knowledge is expected to assist both teaching and material writing. Using a pedagogical genre-based corpus with model answers from teaching material we contrast eight genres to each other based on a set of sixteen features. Each feature is associated with a specific text property. Findings reveal some unexpected relations between pairs of genres and offer insight as to the points of convergence and divergence. It is shown that assumptions made about the similarity of texts which belong to the same text type group can sometimes be mistaken. Therefore, it is argued that the tendency to use general labels for text categories in teaching material may mislead novice writers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Despite the large number of interested parties in the international language proficiency exams and the impact the results of such exams have on the candidates’ lives (e.g. access to jobs, promotions, university entrance and immigration), teaching in this context has not yet incorporated as much insight from scientific research as it should. Mainstream material is still focused on lexis and grammar, the teaching of writing is usually based exclusively on experience and/or intuition and feedback from educators is often vague. Even though the exam writing tasks seem to take genre awareness for granted, in practice, candidates often lack basic knowledge of the genres they will need to write.

This study investigates some of the genres that candidates are frequently asked to write in EFL testing in order to assist teaching and material writing. The aim is to present some of the less obvious features in these genres and provide evidence as to how they relate to each other. The analysis is looking at text properties that come with vague terms such as ‘objectivity and formality’ or ‘authorial stance’. Using existing associations of such properties with specific language features, this paper compares eight written genres regularly seen in English language material. Quantifying similarity and difference can make knowledge about genres explicit rather than implicit and can improve teaching, assessment and material writing.

Literature Review

Several researchers have acknowledged the difficulty in combining ‘linguistic competence’, that is, the mastery of the language code, and ‘communicative competence’ based on pragmatic knowledge (Kroll 1990; McNamara and Roever 2006). ‘Genre theory’ “tries to describe the ways in which we mobilize language”. It is “a theory of the borders of our social world, and our familiarity with what to expect”. (Martin 2009, p. 13). Even though in the development of the child as a social being this familiarity builds up “through the accumulated experience of numerous small events”, (Halliday 1978, p. 9) second language learners need to acquire essential cultural competence through teaching and exposure to representative discourse samples of the new context.

Over the years, three Genre Schools have developed, the ‘Rhetorical Genre Studies’ (RGS, also called ‘New Rhetoric’), ‘English for Specific Purposes’ (ESP) and ‘the Sydney School’, which is based on Systemic Functional Linguistics (Hyon 1996). While all these Schools agree on the importance of genre awareness, they may have a different focus on their analysis. Flowerdew (2002, p. 91,92), classifies them as linguistic (ESP and the Sydney School) and non-linguistic (RGS) approaches and explains their different starting points: “the linguistic approach looks to the situational context to interpret the linguistic and discourse structures, whereas the New Rhetoric may look at the text to interpret the situational context.” The RGS School also differentiates itself on explicit teaching, while the other two Schools, which “emerged out of a pedagogical imperative”, favour explicit genre teaching based on text linguistic analysis (Smedegaard 2015, p. 34).

The Sydney School model, developed in the context of the Australian school system is based on SFL (Systemic Functional Linguistics) theoretical principles and allows for a more systematic approach to teaching (Flowerdew 2015, p. 6). It has provided a detailed description on the use of the terms ‘genre’ and ‘register’ 1 which has been associated with teaching practice in a clear and meaningful way (Board of studies 1998; Knapp 1989; Rose and Martin 2012). According to this view, genres are “staged, goal-oriented, social processes”. They are “social because we are inevitably trying to communicate with readers (even if they do not immediately read or respond to our work), goal-oriented because we always have a purpose for writing and feel frustrated if we do not accomplish it, and staged because it usually takes more than one step to achieve our goals” (Rose and Martin 2012, p. 54). Each genre has some obligatory steps, called stages, considered to be necessary for the achievement of the communicative purpose of the specific genre. These stages have characteristic language features which themselves contribute to the meaning of the whole. Knowledge of these stages in a variety of genres can assist learners’ writing competence.Footnote 1

Using Malinowski’s (1923) terms, ‘context of situation’ meaning the environment of the text, and the ‘context of culture’, meaning the total cultural background, Halliday (1978, p. 5), stresses the importance of studying not only the language or text but also the “total environment in which a text unfolds”. Every day we engage in conversations using mechanisms in a subconscious way in order to adjust. We try to match what is happening with a model of the context of situation in our minds. We assign it to a ‘field’, noting what is going on; we assign it to a ‘tenor’, noticing the persons and their relationships and we assign it to a ‘mode’ seeing what is being achieved by means of language. These three variables are responsible for the configuration of language features in the text. This configuration of language features constitutes the ‘Register’ (Halliday and Hasan 1985, p. 12). The interpretation of context includes two levels of communication, genre (context of culture) and register (context of situation). According to Martin’s schematic representation (1993, p. 156), genre is a layer above register. Thompson (2014, p. 52) explains that a genre “deploys the resources of a register (or more than one register) in particular patterns to achieve certain communicative goals”.

‘Genre awareness’ means that teachers have a conscious knowledge of what makes a text ineffective and how it could be improved. Insight from genre analyses can be used to educate teachers [see for example, the taxonomy of the genres of schooling and the related assessment criteria in Rose and Martin 2012 (pp. 56, 128, 323)]. Despite the notable developments in research, both material and teaching in the EFL context do not seem to benefit much in practice. To support this, we will refer to the two areas of interest in this study, namely Corpus linguistics and Genre Theory.

Corpus linguistics research has been described as a “thriving and productive area of applied linguistics” (Ferris 2011: p. 187). These days, most of the dictionaries for the English language are being produced based on corpus data. Apart from dictionaries though, the picture has not changed much. Even though there have been efforts to produce English language material that is corpus-informed [see for example: ‘Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English’ (Biber et al. 1999), the ‘Touchstone’ series (McCarthy 2004; McCarthy et al. 2005), ‘Cambridge Grammar of English’ (Carter and McCarthy 2006)], course books in general, have remained ‘immune’ to influence from corpus linguistics (Burton 2012; Littlejohn 1992; Meunier and Gouverneur 2009). Research has also shown a lack of awareness of corpus linguistics methods by educators for a number of reasons (Boulton and Tyne 2015; McCarthy and O’Keeffe 2010) which can perhaps explain why the demand for corpus-informed material is low.

Another important change in language education has been the shift which occurred during the 1970 s from ‘formal’ or ‘structural’ to ‘functional’ approaches in language education and from an interest in ‘grammatical competence’ to an interest in ‘communicative competence’ (Hymes 1972). In Chomsky’s (1957,1965) ‘generative grammar’ the emphasis was on the ideal language user producing grammatically correct sentences. That view ignored the context in which language occurs. In contrast, functional grammars started paying attention to meaning (semantics), context or language use (pragmatics) and tried “to explain why one linguistic form is more appropriate than another in satisfying a particular communicative purpose in a particular context” (Larsen-Freeman 2001, p. 34).

Despite these changes, a large number of English language textbooks still present grammar as a discreet component (Hyland 2004) and are often considered weak in providing pragmatic input (Gauci et al. 2017). Feedback is characterised by an obsession with grammatical mistakes (Casanave 2004; Reid 2008) and it is often used as a substitute for explicit guidance in courses where “learners are expected to acquire the genres they need from repeated writing experiences or the teacher’s notes in the margins of their essays” (Hyland 2003, p. 151). The lack of explicit guidance could perhaps be explained by the implicit knowledge of genres the educators themselves have (Christie 1984; Nesi and Gardner 2006) despite the fact that for L2 learners they are often the only models of linguistic and pragmatic competence.

Candidates in English language proficiency exams are supposed to be able to identify the context, the writer’s role and the target reader, and then choose the appropriate register (Cambridge English First handbook 2016, p. 28; Cambridge English proficiency handbook 2016, p. 23). Even though in testing contexts genre awareness is taken for granted, the preparation material seems to lack explicit guidance regarding the identification of the genre and the ways novice writers need to adjust their style.

Methodology

The study investigates eight exam genres from the WriMA (Writing Model Answers) corpus (Melissourgou and Frantzi 2015), a pedagogical corpus consisting of model writing answers presented in educational material. It consists of 1151 model writing answers, (253,025 tokens) from ninety-three different sources (printed and web-based educational material). The choice of model texts for this analysis is influenced by the genre-based ‘Teaching and learning cycle’ (Feez 2002), fundamental in the Sydney school approach and especially the ‘modelling and deconstructing’ stage which “involved setting the genre in its cultural context” (Rose and Martin 2012, p. 64). During this stage, learners read representative texts of the chosen genre, trying to identify its key features and how it moved from one stage to the other. Several researchers support the use of model texts as an important stage in the learners’ immersion in the genre (Derewianka 1990; Flowerdew 1993; Hyland 2004; Knapp 1989; Tardy 2006, 2009). Charney and Carlson (1995) attempt a definition of ‘model texts’:

We will define a model as a text written by a specific writer in a specific situation that is subsequently reused to exemplify a genre that generalizes over writers in such situations. Such models are often used to supplement explicit guidelines or ‘rules’ (provided in a textbook or style guide) for spelling out some of the conventional features of the genre. (p. 90)

Model answers included in the corpus target various international English language exams as the scope was to investigate genres in this context not the preparation for a specific exam. Texts have initially been classified according to text type categories, the way they were presented in educational material. The genres involved in these broad categories have been identified based on SFL principles considering the communicative purpose of the text and the three register variables, field, tenor and mode (for more on the genre identification process see Melissourgou and Frantzi 2017b). Texts in the final sub-corpora are classified based on genre.

The corpus is POS (Part-Of-Speech) tagged with TagAnt 1.1.2 (Anthony 2014) and manually annotated for selected features (text/sentence/paragraph borders, headings, salutations and proper names). Information included in the metadata of the corpus refers to the prompts, the CEFR levels, the name of targeted examination and the source. WordSmith Tools v. 6 (Scott 2015) is used for the analysis.

Eight genres that were shown to be prevalent in educational material and were therefore largely represented in the corpus (sub-corpora with more texts) have been chosen for analysis. Table 1 shows the sub-corpora used as well as the number of tokens and texts included in each sub-corpus.

The study investigates sixteen features in each of these genres. The selection of these features has been based on their prominent role in distinguishing genres observed during a discourse-type analysis of the same genres conducted previously (e.g. Melissourgou 2016; Melissourgou and Frantzi 2017a) and/or their use in genre analyses studies by other researchers. They are selected features from grammatical categories (e.g. pronouns, modals), derivative statistics (e.g. lexical density, Standardised Type/token ratios) and basic text properties (e.g. mean word length, words per sentence).

The sixteen features measured are then linked to specific text properties based on previous studies. The aim here is to explore more than one genre from many different perspectives. For this reason, the analysis does not take into account all possible features that could be linked to a specific text property, only representative features as indicators of a particular property. Table 2 presents the features (left column) and the text properties (right column). High values of the linguistic feature measured in a genre indicate a prevalence of the textual property linked to it.

Increased use of passive verbs has been associated with an ‘abstract style’ (Biber 1995; Glasswell et al. 2001), ‘formality’ (Michos et al. 1996), ‘objectivity and formality’ (Glasswell et al. 2001) and ‘detached writing’ (Czerniewska 1992). The term objectivity and formality is adopted in this study.

‘Lexical density’ has been linked to ‘informational density’ (Fang et al. 2006; Nagy and Townsend 2012). It refers to the ratio of the content or lexical words to the number of tokens in the corpus. We have measured lexical density based on Ure’s method (1971):

‘Nominalisation’ is the use of nouns for meanings that are more typically expressed in a verb, adjective or whole clause (Martin 1985, 1991). Researchers have linked increased use of nominalisation to ‘condensed meaning’ as well as to ‘objectivity and formality’ (Glasswell et al. 2001), ‘objectivity’ (Beck and Jeffery 2007), ‘information density’ (Fang et al. 2006) and an ‘elaborated style’ (Biber 1995). The increased use of nominalisation in this study is associated with ‘objectivity and elaboration’ and has been chosen as a distinctive feature due to its frequent use in certain genres. Biber et al. (1998, p. 62), for example, have observed that nominalisation is more frequently used in academic prose than in fiction or spoken registers. The value for nominalisation here is the sum of the frequencies of the words with the following derivational endings: -tion, -sion, -ness, -ment, -ity, -ship and –ism (filtering out manually nouns that are not instances of nominalisation such as ‘station’).

The ‘type/token ratio’ (TTR) is also a value which is considered important in this analysis as it is usually seen as an indicator of ‘lexical variety’ (Fialho et al. 2012; Viana et al. 2008). High values show that texts include a variety of words and that less words are used repeatedly. The problem with the type/token ratio is that it is highly dependent on text length or corpus size (Biber 2006; Scott 2012). It is informative if dealing with corpora comprising lots of equal-sized texts. For corpora with texts of various lengths, as is the case here, WordSmith Tools (Scott 2015), offers the ‘Standardised Type/ Token Ratio’ (STTR) measurement as a more reliable solution. The researcher has the choice to compute TTR for every n words and get an average based on consecutive chunks of n words.

The following two features, namely ‘word-length’ and ‘number of words per sentence’, have been used in various genre/register studies and belong to a category of features that have been called ‘corpus token-level properties’, ‘shallow discourse features’, or ‘basic text properties’ (e.g. Crossley et al. 2014; McCarthy et al. 2009; Nesi and Gardner 2012; Stamatatos et al. 2001). The length of words (in letters) is often an indicator of ‘lexical complexity’ (Štajner et al. 2015) as it may reveal a more advanced use of vocabulary. The number of words per sentence has been linked to ‘syntactic complexity’ (Michos et al. 1996; Štajner et al. 2015) as it shows an ability to cope with complex sentences. The means for word-length and number of words per sentence are provided in the Statistics section of WordSmith Tools.

Several terms have been used for specific groups of words that tend to appear frequently such as ‘multi-word units’ (e.g. Moon 1997), ‘lexical bundles’ (e.g. Biber et al. 1999) ‘lexical phrases’ (e.g. Lewis 1993), ‘formulaic sequences’ (e.g. Wray and Perkins 2000), ‘clusters’ (e.g. Scott 1997) or ‘n-grams’ (e.g. Kanaris and Stamatatos 2007). There are however, minor differences in what researchers choose to study in this category. We are using the term ‘lexical bundles’ the way Biber et al. (1999, p. 989) see them, as an umbrella term to include formulaic phrases, idioms and recurring “bundles of words that show a statistical tendency to co-occur”. They can give us some idea of the degree of repetitiveness and standardisation of the language used in a genre (Kopaczyk 2012, p. 6). According to Biber et al. (1999), lexical bundles must spread across at least five different texts in a register in order to exclude individual user idiosyncrasies so we have included any three-word lexical bundle that occurs in at least five texts in the sub-corpora. We treat each bundle as a single lexical item and calculate the relative frequency in each sub-corpus in the following way:

Verb tense is also mentioned in genre studies. Glasswell et al. (2001) for example refer to ‘timeless present’ as a feature of explanations, argumentative and persuasive texts. Past tense has often been associated with ‘narration’ (Biber 1995; Czerniewska 1992). In this study, we refer to the use of present simple as ‘Reference to timeless present’ and the use of past simple as ‘Reference to past’.

We include specific connectors as individual analysis of genres at our previous studies corroborated previous findings on the prime role of connectors in accomplishing the purpose of each genre (Glasswell et al. 2001; So 2005). Connectors are grouped according to their functional role in four main groups (a few connectors have been omitted because of their multiple functions):

-

1.

Temporal: after, during, finally, later, next, soon, suddenly, then, when.

-

2.

Adding: also, and, furthermore, in addition, what is more.

-

3.

Contrasting: although, but, despite, however, moreover, on the one hand, on the other hand, whereas, while.

-

4.

Causal/consequential: because, consequently, therefore.

We associate temporal connectors with ‘Events set in time’, adding connectors with ‘Addition’ (Glasswell et al. 2001), contrasting connectors with ‘Contrast’ (So 2005), causal and consequential connectors with ‘Causality’ (So 2005; Glasswell et al. 2001).

Pronouns are important genre markers. Using first person pronouns writers become involved and may adopt a particular stance. Sometimes writers choose to address readers as participants by using the second person pronoun, to pull them into the discourse at critical points and guide them to particular interpretations. In this study, the use of the first person singular pronoun is linked to ‘Involvement’ (Biber 1988) and the use of the second person pronoun is linked to ‘Reader engagement’ (Hyland 2005).

Being part of a larger group called ‘hedges’, modals are often a way to present information as an opinion rather than accredited fact (Hyland 2005, p. 178) and according to Biber (2006, p. 95) they are by far the most common grammatical device used to mark stance in university registers. We refer to the use of modals as an indicator of ‘Authorial stance’ using Hyland’s term.

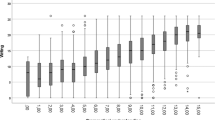

After the initial measurements we convert values to z-scores (using IBM SPSS v. 22 statistics software) in order for them to be translated to a single scale and therefore, be comparable. This offers a point of reference as to the mean; the value for each feature in each genre is contrasted to the values for the same feature in other genres so that it is clear which genre is close to the mean and exactly how close. A z-score is a standardized variable with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of 1. Values that are lower than the mean produce negative scores whereas values that are larger than the mean produce positive scores. To investigate the relations among genres we measure the distance for all possible pairs of genres explored in this study based on each text property. Small distances are interpreted as more similarity on specific text properties. Large distances in many properties indicate weak relations of the genres contrasted.

Analysis and Discussion

The first part of the analysis offered precise measurements concerning each text property within each of the genres investigated here, based on a common scale that allows for comparisons. Due to the large scope of the study (eight genres and sixteen properties) we chose to discuss the results while examining the relations among genres rather than comment in detail on each genre. The figures, however, were considered helpful to anyone interested in specific genres and are provided below (Figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8). Each genre is positively or negatively marked for each text property.

Measuring the distance for each pair of genres and each text property made it possible to investigate the relations among genres in this context. Twenty-eight genre relations were examined overall, contrasted on the same properties. Discussion on text properties links the relevant genre’s communicative purpose and rhetorical moves/stages as well as a sample prompt in order to explain the variation among genres.

The results indicate that the Expository and the Discursive Essay are indeed very similar, justifying the common question about their difference in classrooms. Even though helpful answers can be offered by explaining the main purpose of the two genres and the resulting variation in stages, the explanation can be assisted by showing variation in terms of text properties and related features. Looking at the set of properties investigated in this study, these two genres converge in most properties but there is remarkable distance in Standardized language (distance: 2.6) and Contrast (distance: 2.5), as the Discursive Essay includes a lot more three-word lexical bundles and contrasting connectors (Fig. 9). Educators therefore, could explain that the issue of contrast is really basic in the Discursive essay whereas it is not a typical feature of the Expository essay, and that there is a repetitiveness in the phrases used in the Discursive essay which is not observed in the Expository essay. The following stages are typical of the Discursive essay:

^ Introduction of the issue ^ Argument in favour of one side ^ Argument in favour of the other side ^ Summary of pros and cons + Conclusion in favour of one side.

The main body of the essay is carefully structured to include two paragraphs of arguments concerning the views on the issues discussed. This usually takes the form of two separate paragraphs, one for each side. These paragraphs often open with the phrase [on the one hand] for the first paragraph and [on the other hand] for the second. The opposing view is also introduced with conjunctions such as ‘however’ and ‘while’, often in the pattern [while some people + verb… others + verb].

In the Expository Essay, writers are called to put forward a viewpoint and provide arguments in defence of or as objections to the proposition made. They need to justify their position and reach a conclusion. A common structure of the Expository Essay, is the following:

^ Introduction of the issue ^ Thesis statement ^ Arguments (2–3) ^ Conclusion

In most texts in this corpus the first two to three sentences introduce the issue and the thesis statement is expressed in one sentence right after the introduction. Two to three arguments are put forward, developed and illustrated by examples in most cases, followed by the conclusion in one or two sentences. It is therefore understandable that there is little need for contrast here and that writers have more space to support their opinion (one view) which could be the reason why the language is more original and less standardised. Another reason for the observed recurrent lexical bundles in the Discursive essay could be the fact that it is more common as a task type in exams and subsequently has a larger representation in textbooks in the form of model answers (Melissourgou and Frantzi 2017b). As textbook writers are exposed to the Discursive essay more frequently, there is a greater chance that they will imitate the patterns observed in their own model answers.

The Descriptive essay is relatively close to the Expository essay but the same cannot be said about its relation with the Discursive essay. The divergence is spread across many properties but the two factors that cause difference between the two argumentative essays mentioned above are also responsible for the distance observed here. The Descriptive and the Discursive essay (Fig. 10) are remarkably different in Standardised language and Contrast (distances 3.29 and 2.17 respectively).

The ‘Descriptive Essay’ in this context is about a person, place or event that has impressed the writer. Apart from the detailed description, writers are often asked to explain why this person, place or event has a special place in their heart.[sample prompt]

E.g. Describe a person who has influenced your life and explain why you admire him/her.

Therefore, stages usually follow this pattern:

^ Introduction of the subject of description ^ Extended description ^ Explanation of the writers’ feelings

It is evident that there is little need for contrast here and that there is a strong reference to personal experiences and feelings which calls for a less standardised style of writing. Out of the three essay genres contrasted here, the Descriptive essay seems the least similar to the other two genres in terms of text properties. This is of course further supported by the differentiation in the genre family they are part of—description versus argumentation. In the Expository and the Discursive essays, there is need for some objectivity. Writers need to convince the reader through argumentation and reasoning rather than statements of personal preference. This is manifested in increased use of nominalisation and modals. (e.g. Itcanalso be argued that continuousassessmentis a more effective way of testing some subjects such as design and technology, which are more creative and less academic.—Discursive Essay). In the Descriptive essay, however, writers are asked to write about personal experiences and thus, opinions can be more straight-forward (e.g. Not only was she a good listener, but the advice she offered was always sound as well—Descriptive Essay). During the description of events at the second stage, the use of past tense and temporal connectors is also required whereas in the argumentative genres the timeless present is all the writer needs to support the soundness of the arguments made.

The Data report is close to the Personal observation report but the later converges more to the Expository essay. Personal observation report tasks ask the writers to assess and draw personal conclusions based on subjective views, personal experience and the proximity to a place/service/person. Sometimes the writers are also asked to justify their view/recommendation.

[Sample prompt]

You work for a local magazine. A new take away restaurant has opened in your area. The editor has asked you to visit it and write a report saying whether you recommend it or not.

In general, these reports have the following structure:

^ Introducing the subject and stating the purpose of writing ^ Description of key features (in different sections) ^ Conclusion (± Recommendation + Justification of recommendation).

The Data report tasks usually ask the writers to summarise the information provided, selecting and reporting only the key points. Writers also need to understand where a comparison is useful in presenting this information.

[Sample prompt]

The table shows the Proportions of Pupils Attending Four Secondary School Types Between Between 2000 and 2009. Summarize the information by selecting and reporting the main features and make comparisons where relevant.

The stages in general adhere to the following pattern:

^ Introducing the subject and stating the purpose of writing ^ Description and comparison of key points ^ Conclusion (summary).

As can be seen in Fig. 11 the greatest distance between the two reports is in Lexical variety (2.27). The Data report has a limited set of different words (types). Certain words are used repeatedly at the same position in the text (beginning-middle-end) and are closely connected to specific stages. For example, texts usually begin with the [(type of data) + shows] or [(type of data) + illustrates] where the words ‘chart’, ‘graph’, ‘bar’, ‘line’, ‘pie’ and ‘diagram’ are typical and help the writer introduce the topic. The word ‘overall’ often occurs in the second sentence to give the reader the main trend. Words related to quantity are necessary at the second stage to describe specific parts of the data presented (e.g. percentage, proportion, half, figures, amount). Contrasting conjunctions and verbs reflecting upward or downward trends (e.g. increased, rose, remained), help writers to highlight points of divergence. Patterns related to time are also recurrent at the second stage to assist specificity in description. The repetition of specific words in this genre can be seen as a positive element in teaching situations. Learners do not need a rich repertoire of words; they can write effectively provided they have understood the necessary stages of the genre and their purposes. This way, specific word patterns can be matched to specific parts of the text and practised with different data.

The next large distances are in Authorial stance (1.51), Causality (1.48) and Contrast (1.47). The element of evaluation leaves room for a less assertive style which justifies the use of modal verbs (linked to authorial stance in this study). For instance, modals are used in the Personal Observation Report to suggest improvements, (e.g. although improvementscouldcertainly be made, studentsshouldbe encouraged to). There is little contrast in Personal observation reports, as the focus is usually on one entity while in the Data report comparison is essential. The emphasis is on description of main facts and there is no need for justification while on the other hand the writers of the Personal observation report are often asked to explain why they are recommending a certain location/place/object. Even though Causality is evident in the Personal observational report it is still a negative value which means that it is not a typical feature compared to the rest of the genres. Writers of the Expository essay tend to explain and justify their claims much more frequently. In fact, it is the only large distance observed between the Personal observation report and the Expository essay (1.34) which are very similar otherwise (Fig. 11).

Two interesting issues arise from this evidence. The first is that the group of texts often labelled ‘report’ in teaching material, includes at least two genres (Data report and Personal Observation report) which are similar in many ways but also share four points of noticeable divergence. This supports the early classification of texts in separate sub-corpora for the two genres which was initially based on the task prompts. The second issue has to do with the similarity of a genre that belongs to the broad ‘report’ group with a genre coming from the essay group (Expository essay) and offers evidence in favour of the initial argument that text type categories may not have clear-cut borders.

The last part of this analysis explores two genres from the category of letters. The ‘Complaint Letter’ is connected to some problem the writer has come across, causing inconvenience, which needs to be resolved as soon as possible in order to alleviate frustration and the feeling of injustice. The writer is looking forward to some form of compensation or even a non-materialistic response such as a simple apology coming from a person of high status. A common rhetorical structure for this genre is the following:

^ Purpose of writing ^ Reasons for complaining (description of problem) ^ Expectations

The ‘Advice Letter’ refers to the offer of advice to a friend who has previously asked for help on everyday issues or problems.

[Sample prompt]

Your friend Helen has found a part-time job as a waiter in a café. She’s feeling nervous about her new job. Write a letter to Helen. Give her some advice on how to do well at her job and how to get on with her new colleagues.

The Advice letters investigated here, consistently follow these stages:

^ Reference to previous communication stating the problem ^ Offering advice and justification ^ Expression of hope for resolution ^ Request for further communication and updating

Looking at the distance between the two letters (Fig. 12), there is considerable distance in Objectivity and Formality (2.7) which is connected to the use of passive verbs in this study. The difference in tenor (relation between sender -receiver) in the two letters calls for a personal/friendly tone in the Advice letter and an impersonal/distant tone in the Complaint Letter. Noteworthy distance is also observed in Reference to timeless present (1.67), Authorial stance (1.63), Contrast (1.53), Lexical complexity (1.45), Syntactic complexity (1.43) as well as in Objectivity and Elaboration (1.4). In contrast to the present problem that the writer of the Advice letter is trying to address, the writer of the Complaint letter makes reference to a problem of the recent past. As the description of this problem concerns the second stage and normally the biggest part of the letter, the use of past simple verbs is very frequent. For this genre reference to past is a positive value and reference to timeless present a negative one while for the Advice letter is it the other way round (Figs. 7, 8).

The distance in authorial stance is caused by the main purpose in the Advice letter. Offering advice requires a large number of modals to make polite suggestions that do not sound as commands (e.g. Finally, youshouldmake sure that the place you work makes you feel positive and comfortable./Another thing youcantry is joining a gym). The writers of the Complaint letter on the other hand, need to be firm when asking for compensation or describing facts that cause complaint. At the same time, they need to compare what happened to them with what they were promised. This is part of the second stage (Reasons for complaining) and requires contrasting connectors (e.g. According to your advertisement, the place is perfect for holding private conversations in a relaxing atmosphere.However, it turned out that the music was so loud that we could hardly hear each other). As there is no obvious need for contrast in the Advice letter there is some distance in this feature too.

Compared to the rest of the genres in this study both letters seem to include shorter words (number of letters) and therefore the property of Lexical complexity is negative in both genres. There is however considerable distance between them showing that the Advice letter makes use of short words more frequently; in fact, more than any other genre investigated here. The two letters are also quite different in Syntactic complexity. The Complaint letter includes far more words per sentence than the Advice letter. Short sentences and short words give the Advice letter a lively and friendly tone, perfectly attuned with the tenor of the genre. Finally, the Advice letter is very different from the Complaint letter in Objectivity and elaboration. The use of nominalisation is not necessary in this genre as it does not require an objective tone or sentences dense in information.

Letters are distinguished by the ‘Formal/Informal’ label in exam task types. Even though this differentiation is justified by the results, selecting to stress only one property can obscure the extent of variation between the two categories. The analysis shows that apart from the common general purpose of communication and the surface similarity of correspondence conventions (e.g. greetings), these letters do not form a very strong bond. In fact, the Complaint letter is closer to the Descriptive essay mainly due to its descriptive part (2nd stage) and its extensive use of simple past verb tense.

Conclusion

The study has attempted to assist educators—especially those who prepare students for well-known international English language exams - towards an explicit teaching of genres. The analysis verified that there is a lot of knowledge about genres that remains implicit. Even though some advice is offered by knowledgeable educators, it is mostly based on intuition rather than scientific evidence. Measured features in individual genres, however, can show where the exact boundaries between different genres lie and how each individual feature adds up to the complete and unique character of each genre.

Model writing answers are often presented in writing textbooks under broad text-type labels (e.g. essays, letters) grouping this way a wide range of genres with completely different communicative purposes and writer-reader relationships. This widely used pattern copies the labelling of texts used in exams. The role of educational material, however, is to prepare learners, not test them, and therefore this paper questioned the effect of these umbrella-terms in the presentation of model answers. This grouping of texts creates the natural assumption that texts which are parts of the same category will be more similar to each other than they will be to texts of other categories. Therefore, during the contrast of genres there has been some special interest in those that belong to the same text type group and a focus on the strength of these relations.

The contrastive analysis has validated some expectations on genre relations within the same text type category such as the similarity between the Expository and the Discursive essay. It has, however, offered evidence against the existence of a strong relation between the Descriptive and the Discursive Essay, the two report genres and the two letter genres. Overall this study has shown that the classification of texts in broad categories can in some cases be misguiding, as it conceals internal genre variation. This classification perpetuates the misconception that “different ‘genres’ are quite simply different ‘text types’ each characterised by certain pre-determined textual features” (Tang 2006: introduction). This misconception can also be shared among teachers due to lack of exposure to genre theory and pedagogy (Tardy 2016, p. 175). The results corroborate the view that textual form is a surface trait of the underlying regularity among genres expressed by Freedman and Medway (1994, p. 2) and Lee’s (2001, p. 37) view that ‘genre is the level of text categorisation which is theoretically and pedagogically most useful and most practical to work with’.

This study focused on eight genres which are largely represented in teaching material (Melissourgou and Frantzi 2017b). There are however more genres in this context and future exploration of them for pedagogical purposes is strongly encouraged. Even though there is progress in genre-based studies in academic writing the difference in context means a lot about the kinds of genres explored.

Apart from the gain in pedagogy, we believe these findings can also offer insight to those concerned with ‘automatic genre classification’. The term refers to the need to train computers to classify texts based on genre due to the overwhelming increase in new written material nowadays. Computers need to be taught in order to be able to allocate texts in various categories. This requires deep understanding of genres apart from computational expertise and information which is specific and quantified in order for machines to be able to make use of it.

Building a specialized corpus for this study has been immensely beneficial. Based on strict criteria the WriMA corpus has been a customised tool able to provide answers to complicated questions. Our experience confirms previous remarks in the literature (Flowerdew 1998, 2004) on the significance and contribution of small specialised corpora.

Notes

There is lack of consensus on what exactly these terms stand for in the literature, depending on the researchers’ theoretical background. In order to avoid confusion some studies have tried to clarify the views expressed (for more on this: Melissourgou and Frantzi 2017b; Lee 2001). Due to limited space we explain how the terms have been used in the SFL approach which is also the approach followed in the particular study for the identification of genres and the classification of texts in the corpus prior to analysis.

References

Anthony, L. (2014). TagAnt (version 1.1.2) [Computer Software]. Tokyo: Waseda University. http://www.laurenceanthony.net/

Beck, S. W., & Jeffery, J. V. (2007). Assessing writing. ScienceDirect, 12, 60–79.

Biber, D. (1988). Variation across speech and writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Biber, D. (1995). Dimensions of register variation: A cross-linguistic comparison. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Biber, D. (2006). University language: A corpus-based study of spoken and written registers. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Biber, D., Conrad, S., & Reppen, R. (1998). Corpus linguistics: Investigating language structure and use. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Biber, D., Johansson, S., Leech, G., Conrad, S., & Finegan, E. (1999). Longman grammar of spoken and written English. London: Longman.

Board of studies. (1998). K-6 English syllabus: Modules. Sydney: Board of Studies.

Boulton, A., & Tyne, H. (2015). Corpus-based study of language and teacher education. In M. Bigelow & J. Ennser-Kananen (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of educational linguistics (pp. 301–312). New York: Routledge.

Burton, G. (2012). Corpora and coursebooks: Destined to be strangers forever? Corpora, 7(1), 91–108.

Cambridge English First: Handbook for teachers (2016). Cambridge English language assessment. http://www.cambridgeenglish.org/images/cambridge-english-first-handbook-2015.pdf. Accessed 2 April 2018.

Cambridge English Proficiency: Handbook for teachers (2016). Cambridge English language assessment. http://www.cambridgeenglish.org/images/168194-cambridge-english-proficiency-teachers-handbook.pdf. Accessed 2 April 2018.

Carter, R., & McCarthy, M. (2006). Cambridge Grammar of English: A comprehensive guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Casanave, C. P. (2004). Controversies in second language writing: Dilemmas and decisions in research and instruction. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Charney, H. D., & Carlson, A. R. (1995). Learning to write in a genre: What student writers take from model texts. Research in the Teaching of English, 29(1), 88–125.

Chomsky, N. (1957). Syntactic structures. The Hague/Paris: Mouton.

Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Christie, F. (1984). Varieties of written discourse (section 1, Children Writing: B.Ed. Study guide). Geelong: Deakin University Press.

Crossley, S. A., Allen, L. K., & McNamara, D. S. (2014). A multi-dimensional analysis of essay writing. In T. B. Sardinha & M. V. Pinto (Eds.), Multi-dimensional analysis, 25 years on: A tribute to Douglas Biber (pp. 197–237). Amsterdam- Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Czerniewska, P. (1992). Learning about writing. Oxford: Blackwell.

Derewianka, B. (1990). Exploring how texts work. Newtown: Primary English Teaching Association.

Fang, Z., Schleppegrell, M. J., & Cox, B. E. (2006). Understanding the language demands of schooling: Nouns in academic registers. Journal of Literacy Research, 38(3), 247–273.

Feez, S. (2002). Heritage and innovation in second language education. In A. Johns (Ed.), Genre in the classroom: Multiple perspectives (pp. 47–68). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ferris, D. (2011). Treatment of error in second language student writing (2nd ed.). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Fialho, O., Miall, D. S., & Zyngier, S. (2012). Experiencing or interpreting literature: Wording instructions. In M. Burke et al. (Eds.), Pedagogical stylistics: Current trends in language, literature and ELT (pp. 58–74). London: Continuum.

Flowerdew, J. (1993). An educational, or process, approach to the teaching of professional genres. ELT Journal, 47(4), 305–316.

Flowerdew, L. (1998). Concordancing on an expert and learner corpus for ESP. CALL Journal, 8(3), 3–7.

Flowerdew, J. (2002). Genre in the classroom: A linguistic approach. In A. Johns (Ed.), Genres in the classroom: Multiple perspectives (pp. 91–102). Mahwah: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Flowerdew, L. (2004). The argument for using English specialized corpora to understand academic and professional settings. In U. Connor & T. Upton (Eds.), Discourse in the professions: Perspectives from corpus linguistics (pp. 11–36). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Flowerdew, J. (2015). John Swales’s ideas on pedagogy in genre analysis: A view from 25 years on. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 19, 102–112.

Freedman, A., & Medway, P. (1994). Introduction: New views of genre and their implications for education. In A. Freedman & P. Medway (Eds.), Learning and teaching genre (pp. 1–24). Portsmouth: Boynton/Cook.

Gauci, P., Ghia, E., & Caruana, S. (2017). The pragmatic competence of student-teachers of Italian L2. In I. Kecskes & S. Assimakopoulos (Eds.), Current issues in intercultural pragmatics (pp. 323–345). Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Glasswell, K., Parr, J., & Aikman, M. (2001). Development of the asTTle writing assessment rubrics for scoring extended writing tasks. Technical report 6, project asTTle. Auckland: University of Auckland.

Halliday, M. A. K. (1978). Language as social semiotic: The social interpretation of language and meaning. London: Edward Arnold.

Halliday, M. A. K., & Hasan, R. (1985). Language, context, and text: Aspects of language in a social-semiotic perspective. Oxford/Geelong: Oxford University Press/Deakin University Press.

Hyland, K. (2003). Genre pedagogy: Language, literacy and L2 writing instruction. Journal of Second Language Writing, 16(3), 148–164.

Hyland, K. (2004). Genre and second language writing. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Hyland, K. (2005). Stance and engagement: A model of interaction in academic discourse. Discourse Studies, 7(2), 173–192.

Hymes, D. H. (1972). On communicative competence. In J. B. Pride & J. Holmes (Eds.), Sociolinguistics: Selected readings (pp. 269–293). Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Hyon, S. (1996). Genre in three traditions: Implications for ESL. TESOL Quarterly, 30(4), 693–722.

Kanaris, I., & Stamatatos, E. (2007). Webpage genre identification using variable-length character n-grams. In proceedings of the 19th IEEE international conference on tools with artificial intelligence (ICTAI 2007).

Knapp, P. (1989). Teaching factual writing: The report genre. Sydney: Metropolitan East Disadvantaged Schools’ Program, NSW Department of School Education.

Kopaczyk, J. (2012). Long lexical bundles and standardization in historical legal texts. Studia Anglica Posnaniensia, 47, 2–3.

Kroll, B. (1990). The rhetoric/syntax split: Designing a curriculum for ESL students. Journal of Basic Writing, 9(1), 40–55.

Larsen-Freeman, D. (2001). Grammar. In D. Nunan & R. Carter (Eds.), The Cambridge guide to teaching English to speakers of other languages. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lee, D. (2001). Genres, registers, texts types, domains, and styles: Clarifying the concepts and navigating a path through the BNC Jungle. Language Learning & Technology, 5(3), 37–72.

Lewis, M. (1993). The lexical approach. Hove: LTP Publications.

Littlejohn, A. (1992). Why are ELT materials the way they are? Phd thesis, Lancaster University. http://www.andrewlittlejohn.net/website/books/phd.html. Accessed 2 April 2018.

Malinowski, B. (1923). The problem of meaning in primitive languages. In Supplement 1 to C. K. Ogden and I. A. Richards (Eds.), The meaning of meaning: A study of the influence of language upon thought and of the science of symbolism (8th edn, 1946) (pp. 296–336). NY: Harcourt Brace and World.

Martin, J. R. (1985). Factual writing: Exploring and challenging social reality. Oxford University Press (republished 1989).

Martin, J. R. (1991). Nominalization in science and humanities: Distilling knowledge and scaffolding text. In E. Ventola (Ed.), Functional and systemic linguistics (pp. 307–337). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Martin, J. R. (1993). Genre and literacy: Modeling context in educational linguistics. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 13, 141–172.

Martin, J. R. (2009). Genre and language learning: A social semiotic perspective. Linguistics and Education, 20, 10–21.

McCarthy, M. (2004). Touchstone: From corpus to course book. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://www.cambridge.org/gb/cambridgeenglish/catalog/adultcourses/touchstone/resources/. Accessed 2 April 2018.

McCarthy, M., McCarten, J., & Sandiford, H. (2005). Touchstone 1-4: From corpus to course book. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McCarthy, P. M., Myers, J. C., Briner, S. W., Graesser, A. C., & McNamara, D. S. (2009). A psychological and computational study of genre recognition. Journal for Language Technology & Computational Linguistics, 24, 23–55.

McCarthy, M., & O’Keeffe, A. (2010). What are corpora and how have they evolved? In A. O’Keeffe & M. McCarthy (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of corpus linguistics (pp. 3–13). London: Routledge.

McNamara, T., & Roever, C. (2006). Language testing: The social dimension. London: Blackwell.

Melissourgou, M. N. (2016). The language of reports in general English language testing: A corpus-based analysis. In E. Nichele, D. Pili-Moss, & C. Sitthirak (Eds.), Papers from the 10th Lancaster University postgraduate conference in linguistics & language teaching 2015 (pp. 33–52). Lancaster, UK: Lancaster University.

Melissourgou, M. N., & Frantzi, K. T. (2015). Investigating genre-specific qualities in the Writing part of popular EFL exams. The need for a specialised corpus. In Language in focus 2015 conference, contemporary perspectives on theory, research and praxis in ELT and SLA book of abstracts (p. 64). Cappadocia: Language in Focus.

Melissourgou, M. N., & Frantzi, K. T. (2017a). Register analysis based on corpus evidence: The case of Reports in IELTS. Language in Focus, 2(2), 70–87.

Melissourgou, M. N., & Frantzi, K. T. (2017b). Genre identification based on SFL principles: The representation of text types and genres in English language teaching material. Corpus Pragmatics, 1(4), 373–392.

Meunier, F., & Gouverneur, C. (2009). New types of corpora for new educational challenges: Collecting, annotating and exploiting a corpus of textbook material. In K. Aijmer (Ed.), Corpora and language teaching (pp. 179–201). Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins.

Michos, S. E., Stamatatos, E., Fakotakis, N., & Kokkinakis, G. (1996). Categorising texts by using a three-level functional style description. In A. Ramsay (Ed.), Artificial intelligence: Methodology, systems, applications, frontiers in artificial intelligence and applications (Vol. 35, pp. 191–198). Amsterdam: IOS Press.

Moon, R. (1997). Vocabulary connections: Multi-word items in English. In N. Schmitt & M. McCarthy (Eds.), Vocabulary description, acquisition and pedagogy (pp. 40–63). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Nagy, W., & Townsend, D. (2012). Words as tools: Learning academic vocabulary as language acquisition. Reading Research Quarterly, 47(1), 91–108.

Nesi, H., & Gardner, S. (2006). Variation in disciplinary culture: University tutor’s views on assessed writing tasks. In R. Kiely, G. Clibbon, P. Rea-Dickins, & H. Woodfield (Eds.), Language, culture and identity in applied linguistics (Vol. 21, pp. 99–117)., British studies in applied Linguistics London: Equinox Publishing.

Nesi, H., & Gardner, S. (2012). Genres across the disciplines: Student writing in higher education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Reid, J. (2008). Myth(s) 9: Students’ myths about academic writing and teaching. In J. Reid (Ed.), Writing myths: Applying second language research to classroom teaching (pp. 177–201). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Rose, D., & Martin, J. R. (2012). Learning to write, reading to learn: Genre, knowledge and pedagogy in the Sydney School. London: Equinox.

Scott, M. (1997). PC analysis of key words and key key words. System, 25(1), 1–13.

Scott, M. (2012). WordSmith tools help. Stroud: Lexical Analysis Software.

Scott, M., (2015). WordSmith tools version 6. Stroud: Lexical Analysis Software. http://lexically.net/wordsmith/. Accessed 2 April 2018.

Smedegaard, A. (2015). Genre and writing pedagogy. In S. Auken, P. S. Lauridsen, & A. J. Rasmussen (Eds.), Copenhagen studies in genre 2, genre and. Copenhagen: Forlaget Ekbátana.

So, B. P. C. (2005). From analysis to pedagogic applications: Using newspaper genres to write school genres. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, 4(1), 67–82.

Štajner, S., Mitkov, R., & Pastor, G. C. (2015). Simple or not simple? A readability question. In N. Gala, R. Rapp, & G. Bel-Enguix (Eds.), Language production, cognition and the lexicon (pp. 379–398). Switzerland: Springer.

Stamatatos, E., Kokkinakis, G., & Fakotakis, N. (2001). Automatic text categorization in terms of genre and author. Computational Linguistics, 26(4), 471–495.

Tang, R. (2006). Helping students to see “Genres” as more than “Text Types”. The Internet TESL Journal, XII (8). http://iteslj.org/Techniques/Tang-Genres/.

Tardy, C. (2006). Researching first and second language genre learning: A comparative review and a look ahead. Journal of Second Language Writing, 15, 79–101.

Tardy, C. (2009). Building genre knowledge. West Lafayette: Parlor Press.

Tardy, C. M. (2016). Beyond convention: Genre innovation in academic writing. The Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Thompson, G. (2014). Introducing functional grammar (3rd ed.). London and New York: Routledge.

Ure, J. (1971). Lexical density and register differentiation. In G. E. Perren & J. L. M. Trimm (Eds.), Applications of linguistics: Selected papers of the 2nd international congress of applied linguists (pp. 443–452). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Viana, V., Giordani, A., & Zyngier, S. (2008). Empirical evaluation: Towards an automated index of lexical variety. In S. Zyngier, M. Bortolussi, A. Chesnokova, & J. Auracher (Eds.), Directions in empirical literary studies: In honor of Willie van Peer (pp. 271–282). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Wray, A., & Perkins, M. (2000). The functions of formulaic language: An integrated model. Language & Communication, 20(1), 1–28.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Melissourgou, M.N., Frantzi, K.T. Moving Away from the Implicit Teaching of Genres in the L2 Classroom. Corpus Pragmatics 2, 351–373 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41701-018-0033-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41701-018-0033-3