Abstract

This article analyses the business cycle dynamics in the European Union (EU28) during recent decades. Following Camacho et al. (J Econ Dyn Control 30:1687–1706, 2006), we extend the analysis of European cycles to a broader range of countries, including new entrants. In addition, we update their sample by including the Great Recession data with the aim of exploring whether the financial crisis led to changes in cyclical features across these countries. Our results indicate that the Great Recession has undermined European cyclical linkages. Notably, we succeeded in detecting that the European economies do not follow more closed dynamics, despite the fact that the countries are showing more similar cyclical characteristics.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

This methodology is a refinement of the dating algorithm for monthly data suggested by Bry and Boschan (1971). Although is it possible to employ a different algorithm, such as the Markov Switching model proposed by Hamilton (1989), the literature has successfully proved the preference of BBQ over other methods due to being the most effective, easy and having the fewest restriction requirements (see Ahking (2015) on this issue).

McDermott and Scott (2000), Harding and Pagan (2002), Krolzig and Toro (2005) and Harding and Pagan (2006) regard the use of the concordance index as being a better tool in measuring business cycle synchronization. As advocated by Harding and Pagan (2002) and McDermott and Scott (2000) the concordance indicator is a better metric, focusing on the fraction of time when the reference cycle and the specific cycle are in the same state.

This is except for France, Sweden, Austria and Spain, whose samples have had to be shortened, since the dating of the cycles is made by the ECRI, which only provides data from 1953 for France and 1969 for the other 3 countries.

The moment that we consider the crisis started for each of the countries is clarified in Table 1. It has been determined based on the peak that the countries showed during the years 2007–2008.

Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus and Slovenia have been excluded from the sample due to lack of a complete business cycle during the period before the crisis.

Bulgaria, Croatia, Cyprus and Slovenia have also been deleted from the sample of synchronization due to the interference that they provide as consequence of little data.

We are aware of the sensitivity of Euclidean distances to outliers and composition of the sample itself.

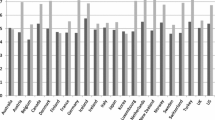

Note that in these maps, axes are meaningless; thus, they have been deleted. Every MDS map plots the country code, whose meanings are collected in Table 1—Data description.

In every MDS map, the founders and oldest members of the European Union are represented in red, the members who acceded between 1973 and 1995 are plotted in blue, and the new members, since 2004, are represented in black.

The completed results of the exercise with the reduced samples are available upon request.

References

Ahking, F. W. (2015). Measuring U.S. business cycles: A comparison of two methods and two indicators of economic activities. Journal of Economic and Social Measurement,39, 199–216.

Ahlborn, M., & Wortmann, M. (2018). The core-periphery pattern of European business cycles: A fuzzy clustering approach. Journal of Macroeconomics,55, 12–27.

Antonakakis, N., Chatziantoniou, I., & Filis, G. (2016). Business cycle spillovers in the European Union: What is the message transmitted to the core? The Manchester School,84(4), 437–481.

Bierbaumer-Polly, J., Huber, P., & Rozmahel, P. (2016). Regional business-cycle synchronization, sector specialization and EU accession. Journal of Common Market Studies,54(3), 544–568.

Bry, G., & Boschan, C. (1971). Cyclical analysis of time series: Selected procedures and computer programs. National Bureau of Economic Research.

Camacho, M., Caro, A., & Lopez-Buenache, G. (2018). The two-speed Europe in business cycle synchronization. (Working paper).

Camacho, M., Perez-Quiros, G., & Saiz, L. (2006). Are European business cycles close enough to be just like one? Journal of Economic Dynamics & Control,30, 1687–1706.

Camacho, M., Perez-Quiros, G., & Saiz, L. (2008). Do European business cycles look like one? Journal of Economic Dynamics & Control,32, 2165–2190.

Cox, T. F., & Cox, M. A. (2000). Multidimensional scaling. London: Chapman and Hall.

Darvas, Z., & Szapáry, G. (2008). Business cycle synchronization in the enlarged EU. Open Economies Review,19(1), 1–19.

De Haan, J., Inklaar, R., & Jong-A-Pin, R. (2008). Will business cycles in the euro area converge? A critical survey of empirical research. Journal of Economic Surveys,22(2), 234–273.

Degiannakis, S., Duffy, D., & Filis, G. (2014). Business cycle synchronization in EU: A time-varying approach. Scottish Journal of Political Economy,61(4), 348–370.

Feldstein, M. (1997). The political economy of the European Economic and Monetary Union: Political sources of an economic liability. Journal of Economic Perspectives,11(4), 23–42.

Gomez, D. M., Ortega, J. G. & Torgler, B. (2012). Synchronization and diversity in business cycles: A network approach applied to the European Union. (CREMA Working Paper).

Grigoraş, V., & Stanciu, I. E. (2016). New evidence on the (de)synchronisation of business cycles: Reshaping the European business cycle. International Economics,147, 27–52.

Hamilton, J. D. (1989). A new approach to the economic analysis of nonstationary time series and the business cycle. Econometrica,57(2), 357–384.

Harding, D., & Pagan, A. (2002). Dissecting the cycle: A methodological investigation. Journal of Monetary Economics,49, 365–381.

Harding, D., & Pagan, A. (2006). Synchronization of cycles. Journal of Econometrics,132(1), 59–79.

König, J., & Ohr, R. (2013). Different efforts in European economic integration: Implications of the EU index. JCMS,51(6), 1074–1090.

Krolzig, H., & Toro, J. (2005). Classical and modern business cycle measurement: The European case. Spanish Economic Review,7, 1–22.

McDermott, C. J., & Scott, A. (2000). Concordance in business cycles. (Technical report, IMF).

Silverman, B. W. (1981). Using kernel density estimates to investigate multimodality. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological),43, 97–99.

Wortmann, M., & Stahl, M. (2016). One size fits some: A reassessment of EMU’s Core-periphery Framework. Journal of Economic Integration,31(2), 377–413.

Funding

This funding was granted by Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte (Grant No. FPU/04594).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

See (Fig. 11, Tables 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13).

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Rodríguez-Santiago, A. What has Changed After the Great Recession on the European Cyclical Patterns?. J Bus Cycle Res 15, 121–146 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41549-019-00038-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41549-019-00038-7