Abstract

To better understand policy integration dynamics, this paper analyses the early implementation of three urban food policies in France (Montpellier, Rennes, Strasbourg). A key challenge of food policies is their intersectoral nature, while policy design is usually meant to be sectoral. This article seeks to understand both levers and brakes to the implementation of effective integrated policies at the urban level. To explore the making and “everydayness” of the three policy case studies, we collected empirical data based on a multi-faceted methodology comprising a wide review of the grey literature, 29 in-depth interviews, and several series of participant observations on the ground. Our analysis indicates that dedicated organisational resources, including assigned units, trained staff and appropriate financial resources, are keys to the deployment of integrated food policies. We argue that such organisational resources should be more systematically studied in the policy integration literature. Local food policies should also be assessed more critically by putting the organisational resources they receive into perspective with the massive use the local government can make of them for communication purposes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The food we eat is at the centre of a complex system of interactions and a growing body of research is showing how capitalist food systems have a negative impact on both public health (Neff et al., 2015) and the environment (Lang & Barling, 2013). Transition to sustainable food systems requires not only changing our diets (Goodman et al., 2012) but also shifting food system governance towards more integrated policies (De Schutter et al., 2020; Lang & Barling, 2012). Although national food strategies are emerging in many countries, implementing “integrated” political management of a food system that simultaneously addresses all food-related issues is challenging and truly integrated food policies are far from being achieved (Candel & Pereira, 2017). As an illustration, French public policies explicitly labelled as “food policies” are twofold, focusing on nutrition on the one hand and on food quality market segmentation on the other hand, and it is notable that other ministries than the ministry of Agriculture were only very recently included in their making (Fouilleux & Michel, 2020). Although food and agricultural policies are increasingly open to new concerns (provision of ecosystem services, animal welfare, biotechnology, etc.) (Daugbjerg & Swinbank, 2012), national governance structures of the food system are still administered in silos (Fouilleux, 2021; IPES-Food, 2017). In contrast, several authors emphasise the fact that local policiesFootnote 1 are probably more capable of embracing the complexity of food systems. Territorial policies are sometimes analysed as synonyms of cross-sectoral approaches, either because they connect to the network of local actors in a horizontal and concerted manner (Southern, 2002; Hemphill et al., 2006), or because they adapt their public actions to local specificities (Trouvé et al, 2007). Among territorial policies, urban food policies are a good example of this recognition of the interconnected nature of food system challenges (Sibbing et al., 2021; Sonnino et al., 2019; Sonnino, 2017; Mansfield & Mendes, 2013) and “a trend to link specific policies and programmes through comprehensive urban food system strategies or plans” has been noted (Baker & de Zeeuw, 2015).

Thus, after a period during which these issues were neglected, cities now seem to be increasingly interested in food issues, driven by citizens’ enthusiasm and by rising concerns including increasing urban food insecurity (Brand et al., 2019; Pothukuchi et al., 2000; Steel, 2013). This situation is even more acute in times of conflict and global trade disorders as the Russo-Ukrainian War revealed in 2022. Urban food initiatives are mushrooming and a network for connecting and sharing experiences among cities, the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact,Footnote 2 has even been created. Addressing food issues now appears to be compulsory for urban governments (Cretella, 2016; Dubbeling et al., 2015; Moragues-Faus & Morgan, 2015). Various institutional innovations have appeared, including food councils and urban food strategies (Jarosz, 2008; Morgan, 2015). In France, urban food policies are proliferating too (Brand, 2017) even though food regulation does not fall under the mandatory competence of local authorities. The growing literature that addresses urban food policies focuses on their scope (Candel, 2020; Sibbing et al., 2021), their institutionalisation (Sibbing & Candel, 2021), or their governance (Santo & Moragues-Faus, 2019; Termeer et al., 2018) but their practical implementation or “everydayness” remains understudied. In this paper, we analyse three French urban food policies with the aim of answering the following questions: beyond paper realities, how are urban food policies being implemented in municipalities, and how do they adress the intersectoral nature of the food system concretely?

We compare food policies in three French urban areas, one metropolitan area with 500,000 inhabitants (Montpellier), one city area with 215,000 inhabitants (Rennes), and one case of a city food policy backed by a metropolitan government (Strasbourg, 280,000 inhabitants).Footnote 3 Our analysis targeted an in-depth understanding of early stages in the conception and implementation of these urban food policies. The food policy of Rennes is called the “City of Rennes sustainable food plan” (Plan Alimentaire Durable de la ville de Rennes). It was initiated in 2014 right after the municipal election, was formally launched in 2017, and ran until 2020.Footnote 4 The food strategy of Strasbourg is called the “Development strategy for local, sustainable, and innovative agriculture that meets the population’s food needs” (“Stratégie de développement d’une agriculture locale durable et innovante répondant aux besoins alimentaires de la population”). It was initiated in 2008 right after the municipal election and has since been regularly renewed. Montpellier metropolitan area’s food policy is called “Montpellier metropolitan area policy for agroecology and food” (Politique Agroécologique et Alimentaire de la Métropole de Montpellier). It was initiated in 2014 and voted in 2015. The three food policies were initiated after municipal elections with no major political changeover. Nevertheless, these elections were an opportunity to update the policies already implemented, backed against new political coalitions (in the case of Rennes) and citizen activism (Montpellier and Strasbourg).

The first author collected empirical data on these three cases between 2016 and 2019. In addition to a wide review of the grey literature, she conducted 29 in-depth interviews with key stakeholders, including six elected officials (two in each study area), seven municipal/metropolitan agents (ibid), and 16 private or institutional partners involved in these policies. In addition, she undertook several series of participant observations on the ground, such as attending internal meetings and official events in the three cities.Footnote 5 Our enquiry covers a mid-range period, from the early 2000s to 2019.

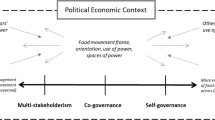

In this paper, our key issue is to understand intersectoral/integrated policies in the making while policy design is usually meant to be mainly sectoral. We chose to use the multi-dimensional framework of policy integration proposed by Candel and Biesbroek (2016), a reference in the policy study literature, which allows to explore policy integration dynamics. We use this analytical framework as a starting point to analyze the empirical material collected on our three urban food policies, and discuss the model based on both our literature review and our analytical results.

In the following sections, we first present our theoretical framework, which combines Candel and Biesbroek’s model and some insights from the literature on urban food policies. In the second section, we explore how cross-cutting food system issues were put on the political agenda of the three cities, in other words, how the need for integration was politicised. In the third section, we trace the multitude of partnerships established within the framework of these policies. In the fourth section, we show that despite positive indicators of political integration, the implementation of all three urban food policies suffers from serious organisational difficulties: lack of a specific administrative unit, understaffing, and low budgets committed. In the fifth section, we discuss the importance of considering the organisational resources dimension (including the allocation of appropriate budgets, the creation of specific units, and the appointment of trained staff) when it comes to assessing policy integration dynamics, a dimension not adequately highlighted in Candel and Biesbroek’s model.

Exploring urban food policy integration

Candel and Biesbroek (2016) define policy integration “as an agency driven process of asynchronous and multi-dimensional policy and institutional change within an existing or newly formed governance system that shapes the system’s and its subsystems’ ability to address a cross-cutting policy problem in a more or less holistic manner” (p. 217). To study such a process, they propose a multi-dimensional analytical framework with four main dimensions: policy frame, policy goals, subsystem involvement, and policy instruments. First, the policy frame dimension refers to the “problematisation” stage, i.e. the way in which problems are conceived and enounced and from which the proposed political solutions directly derive. This concept, which points to a constructivist approach to social problems, stresses the direct link between a policy and the perception of the social problem by policy makers translated into policy goals or instruments. For high amounts of policy integration, the cross-cutting problem must be recognised as such. The second dimension is “subsystem involvement”, which refers to the groups of actors and institutions involved (or not) in making the policy. It combines two indicators: the variety of actors involved in the governance of the cross-cutting policy problem, also considering subsystems which are not involved (but could be), and the density of interactions between formally involved subsystems (how often they have the lead in developing policy proposals). The more varied the stakeholders and the higher their level of interaction, the better the policy integration is supposed to be. Third, the dimension of “policy goals” refers to the range of policies in which resolving the cross-cutting problem is adopted as a goal, and the degree of policy coherence within a governance system in relation to this cross-cutting problem. The fourth dimension concerns the policy instruments implemented to achieve the goals, whether substantive or procedural. This dimension includes three indicators. First, the very existence of policy instruments within all potentially relevant subsystems and associated policies. Second, the setting up of procedural instruments at governance system level in order to coordinate subsystem policy efforts, whether overarching strategies and funding programmes, constitutional provisions, consultation mechanisms, impact assessments, or interdepartmental working groups, inter-alia. Finally, the consistency of policy instruments mixes at subsystem level. To sum up, the broader the range of subsystem policies that contain policy instruments targeting a given problem, the broader the range of procedural instruments at the system level, and the more consistent they are, the higher the degree of policy integration is supposed to take place.

Such an analytical framework is both very complete and easily applicable, but some aspects would benefit from being clarified. First, regarding the first and third dimensions, the literature shows that a gap may exist between the normative framework used by policy-makers in their speeches or programmes and their actual actions (Okner, 2017). It is therefore important to compare the rhetoric of these policies and the resources and actions that operationalise them. In other words, the various dimensions of policy integration processes must be analysed simultaneously and not one by one. Similarly, in line with the second dimension, some studies have highlighted the need for increased pluralism to make integrated food policies possible (e.g. Drimie & Ruysenaar, 2010). However, considering only one group of actors in a subsystem may not be sufficient to grasp the complexity of the problem, even if a great diversity of subsystems is involved in the process. Indeed, several groups of actors with radically different political agendas may coexist in the same subsystem. For instance, addressing food production with only dominant actors of agricultural subsystem can lead to narrowing the scope of the food policy (Mumenthaler et al, 2020; Pahun, 2020). Moreover, taking the environmental or social impacts of the food system into consideration cannot be guaranteed solely by the diversity of stakeholders and the intensity of their interactions, whether they are in one subsystem or divided among different ones. The balance of power between stakeholders, which has both contextual and structural determinants, also matters, and directly determines their respective influence on the policy implementation processes (Benoit & Patsias, 2017). Thirdly, and this is the point we address in particular in this article, Candel and Biesbroeck overlook an important aspect that may play a key role in explaining the success or failure of integrated urban food policies related to resources made available to the policy. Recent research on food policy institutionalisation acknowledges that “budget and organisational innovations seem to be keys in this process, although they can also be constraining” (Sibbing & Candel, 2021). Some of these elements are embedded in the instrumental dimension of the analytical framework. However, since constraints related to budgets, human resources, and staff support are among the most frequently cited factors responsible for food policy failures we argue these elements may constitute an additional dimension of the multi-dimensional framework of policy integration that we term “organisational resources dimension”. Many illustrations of the importance of this fifth dimension can be found in the food policy literature.

The first example is the London Food Strategy, which has been described as a policy with little or no real transformational capacity of the urban food system due to lack of resources and a weak city-wide governance system. The mayor has little or no direct control over the activities that he seeks to influence (healthy schools canteens). And “although the public sector is an important part of this foodscape, not least the schools and hospitals that supply 110 million meals a year in London, this is just a fraction of the estimated 8 billion meals that are consumed annually in the capital” (Morgan & Sonnino, 2010, p. 218). Another example is the food policy of Vancouver. Wendy Mendes (2008) assesses the capacity of the government of Vancouver to implement its food policy through five factors: legal status and mandated role, staffing support, integration of food policy into normative and legal frameworks, involvement of joint-actor partnerships, and citizen participation mechanisms. Among these factors, staff support is described as critically important to ensure the long-term stability of a food policy: “the benefits of assigned food policy staff are argued to include consistent leadership, organisational stability, keeping food system goals on the radar of local governments and avoiding lapses in activity policy agenda setting” (p. 954). Yet, stabilising a specific food unit seems to be key to the institutionalisation of the policy.

The literature has abundantly shown the key role played by administrations in public policy implementation and, as a result, in the success or failure of the policy (Skocpol & Finegold, 1982). First, the stability of metropolitan/municipal staff ensures a certain continuity in public action, in contrast with the time-bound mandates of elected officials. While municipal elections always lead to uncertainties concerning policy priorities, such uncertainties may compromise the very existence of food policy, as illustrated by the case of Belo Horizonte, one of the world’s pioneer urban food policies (Rocha & Lessa, 2009). Generic studies also highlight the political role played by public administrations (Dion, 1986). Departments and units play a role in the development of intermediate decisions, contribute to public policy legislation or regulations (Page & Jenkins, 2005), and influence the implementation of public policy instruments (Svara, 1985). Administrations also have “power of intermediation” thanks to their position at the interface between elected officials and interest groups or citizens (Peters, 2002). In this context, there is a close interdependence between sectoral administrations and their target population. The notion of “administrative constituency” underlines the tendency of administrations to sometimes communicate exclusively with their target population in order to secure their support and strengthen their authority or action in a given sector (Selznick, 1980). Therefore, the importance of diversifying alliances as underlined by Candel and Biesbroek also concerns the administrative level itself. Yet, beyond the specific competences of the administration and its favoured interfaces, how public policies are implemented also very concretely depends on the allocation of budgets (Elliott & Salamon, 2002).

Studying these concrete elements of food policies is also a way of making a clear distinction between what concretely concerns the deployment of the policy and what comes under the heading “policy communication”. Indeed, urban food policies are often used by local authorities for communication purposes. For instance, in the case of the Olympic Games held in London in 2012, the food policy was used to serve the promise to deliver the “most sustainable games ever” (Morgan & Sonnino, 2010). In this paper, we argue that the analysis must go beyond the illusion of symbolic programmes, short-term public actions, or regional marketing-oriented strategies, explore the concrete organisational means made available, and assess the amounts of resources actually dedicated to the policies under scrutiny. Integrated urban food policies need stabilised dedicated administrative recognition, staff support, and adequate funding in the long run in order to be implemented effectively and efficiently. They might then possibly have a transformative impact on the food system.

Problematising cross-sector food policy issues, politicising integration

In the following section, we review the policy frames and goals of the urban food policies of Strasbourg, Rennes, and Montpellier. As we focus on local government and integrated policy implementation, we do not consider how local organisations involved in food policy advocacy managed to put food issues on the political agenda, but rather how the three female politicians in charge of the food policies reshaped and stabilised the goals of these policies. This section is mostly based on an analysis of the discourse of the three elected officials who lead these policies to study how they politicised the need for policy integration.

Local food supply as a social cement in the Strasbourg area

Strasbourg’s food policy was initiated by a woman who had, until then, “never been involved in public affairs”.Footnote 6 In 2006, she led a community fight for the creation of food halls in the city centre and was spotted by local socialist officials who then put her on the list of candidates for the 2008 municipal election. After the election, she was appointed deputy mayor in charge of the environment, green spaces, and agriculture. Resulting from her awareness of local food systems through her work as a restaurateur and her personal involvement in a local community-supported agricultural association, her first political goal was to develop the short food supply chains. She also advocated for fair trade between urban consumers and farmers. She began her assignment with the diagnosis of short food supply chains in the Strasbourg area. This work was supported by the metropolitan government, which made available one agent full-time to prepare and then implement the policy. This diagnosis revealed a major disconnection between peri-urban agricultural production and the city: 70% of agricultural land was being used for large-scale crop production (especially maize) and 21% for fodder or sugar crops mainly grown for export and for the food processing industry. In addition, only 0.5% of the total utilised agricultural land was organic. Although “originally it was not about agriculture, but about the distribution of local products”,Footnote 7 the now deputy mayor realised that in order to secure local supply, the local agricultural landscape had first to be changed through diversification, supporting market gardeners and encouraging organic farming. Such transformations involve major changes in practices, which cannot be imposed on farmers. She underlines: “we can’t walk in and tell the farmers that what they do doesn’t suit us. […] We must look at the questions of food autonomy and governance again”.Footnote 8 Thus, she considered food system issues as a link to the countryside and as a safe gateway towards more sustainable agricultural practices, avoiding expected tensions with historical partners in this sector. The food policy signed in Strasbourg in 2008 demonstrated a strong will to change agricultural practices, towards “organic farming, market gardening, consumption of local products or decreasing the cultivation of maize. The concept is that agriculture should be economically sustainable for farmers while meeting consumer desires”.Footnote 9 The deputy mayor sees this programme as a proxy for a renewed social connection between farmers (better income) and eaters (more satisfied with their food). The idea of “connection” is recurrent in her discourse: dialogue with peri-urban farmers must be re-established and farmers must also be reconnected with urban eaters, through events mixing urban audiences and farmers, support to create local farm shops in the city, etc.

City of Rennes: school canteen supply as a means to achieve agricultural and environmental change

The female politician who launched the Rennes’ food policy had campaigned with the green party, Europe Ecologie Les Verts (EELV), in the 2014 communal election. Thanks to obtaining 15% of the votes in the first round of the election, the EELV political group was able to merge with the Socialist Party (PS) in the second round. The introduction of organic products in the city’s primary school canteens was discussed during the programmatic negotiations related to the merge. EELV wanted half of the food served to be certified organic. Negotiations with the PS finally set the proportion at 20%. After the elections, an EELV representative was appointed to put these ideas into action. She used this opportunity to implement broader agro-environmental policies and support social economy and local development. Beyond what is put on children’s plates, she was interested in how this could be used to regulate agricultural practices and associated pollution, seeing “the city’s supply policy [as] a key lever to push agriculture towards more sustainable methods”.Footnote 10

By “sustainable”, she means environmentally friendly agriculture which at least complies with organic farming certification rules. In contrast to the Strasbourg city official’s discourse, the origin of the food is not central here: “even better if it is local, but interesting only if it is organic, so we can support specific supply chains. We are not trying to hide that. Getting everyone on the organic wagon is the objective”.Footnote 11 This goal is written in the introduction of the city’s food programme, in which it is depicted as a “shift towards agro-ecology” for the city’s supply area. It promotes “a balanced diet, concerned with sustainable development, and based on a strong link between producers and consumers. A diet that can also tackle carbon emissions”.Footnote 12 As a renewable energy engineer, she considers that energy efficiency is a key element of sustainability. Using the school supply channels, she was therefore aiming to address agricultural, environmental, and energy issues at the same time.

Food policy as a unifying political project, the example of the metropolitan area of Montpellier

First elected in 2014 as mayor of a small town of the Montpellier conurbation where she led a battle against urbanisation, the politician who initiated the metropolitan food policy was previously a member of EELV. She was appointed by the socialist mayor of Montpellier, president of the metropolitan council, and she became the Vice-Chair in charge of small and medium-sized enterprises, craftsmanship, rurality, and traditions. As a trained agronomist and deputy director of the public institute of higher education in agricultural sciences of Montpellier, her initial political desire was to address “agriculture and agroecology sustainability issues”Footnote 13 and to support the establishment of new farmers near the city. To identify leverage actions, she consulted local researchers and the top management of the metropolitan administrative units (economy, urbanism, planning) as well as the mayors of the 31 cities that are members of the metropolitan community (Michel & Soulard, 2017). Throughout the year of consultations, she took note of the fact that local stakeholders were more enthusiastic about school canteens, outdoor markets, and food than about agricultural topics, which made them more inclined towards a food policy. Keeping her agricultural ideas in mind, she gradually included food issues in her work: “food was more unifying. Having both words mentioned in my mandate gave me access to all the city’s units and what was happening there”.Footnote 14 She then proposed an “agroecology and food policy” to the metropolitan Council in 2015, and obtained a unanimous vote. The policy aimed to support “small-scale agriculture, whether individual or collective”,Footnote 15 which was defined by the representative as all practices including economical, ecological, social, or educational interests in the urban area and traditionally associated with small-scale farming. She opposed the model of “big capitalistic agricultural businesses, those huge companies” who own huge farms with few employees which is a common phenomenon in the plains surrounding Montpellier. “They have hundreds of hectares of CAP-supported durum wheat where we could have bread-baking farmers instead!”.Footnote 16 During our interviews, she insisted on the ideas of territory networking, job creation, and social links around agricultural and food activities.

The many goals of the three urban food policies

In the three cases studied, we noted that all the urban food strategies formulated are multi-dimensional, although only partially as they do not include health issues for example. We also noted that, prior to the arrival of these newly elected politicians, food issues were not explicitly on the agenda of the three cities. While several actions affecting the food system were already being implemented by previous urban governments, they were not thought of as part of a comprehensive food strategy. The three elected women have imported food issues as a new policy on the political agenda after a gradual understanding of the multidimensionality of food issues, resulting from both their professional backgrounds in catering, energy engineering, or agronomy, and their practice of power (recognition of action leverage, room for manoeuvre for political compromise, etc.). Initially focused on a relatively narrow objective, the three urban food policies were then extended to other food system issues (eventually including agricultural, environmental, and social concerns) as summarised in Table 1.

As illustrated in Table 1, the three policies address the cross-cutting food problem in a more or less holistic way. Although public health or fairness issues do not appear explicitly in these policies, they were occasionally or indirectly mentioned by our interviewees. For example, this was the case regarding access to fresh and seasonal products by citizen consumers and the improvement of public services and supplies to school canteens.

Food policy stakeholders: new partners for urban governments

In this section, we review the involvement of subsystems, i.e. the way stakeholders are involved in the three local food policies studied here, with an aim of exploring their diversity. Two main features of this diversity is the inclusion of a variety of stakeholders coming from various subsystems, and the inclusion of alternative food networks (promoting small scale organic agriculture) in addition to conventional actors (promoting industrial chemical-based agriculture).

The diversity of stakeholders involved in urban food policies

The three elected officials in each metropolitan area under study worked with many stakeholders to justify the way they tackle food-related issues and implement the policy: researchers, consultants, citizen organisations, water quality agencies, etc. Whether through occasional collaborations (technical expertise, project management assistance, information meetings) or longer-term partnerships. These collaborations enabled the representatives to gain new skills and the acceptance of new ideas within their administrations.

The example of the partnership strategy of the city of Rennes illustrates how partnerships can be a major political asset for food policies. For the elected official in charge of the food policy in Rennes, introducing weekly vegetarian meals in the city’s primary school canteens had many advantages. One was saving money, meaning more could be spent on top quality meat for the rest of week. Showing children that meat is not the only source of protein was another. However, she had to “fight” to legitimise her actions and push for acceptance from both the other elected officials of the municipality and the nutritionist in the central kitchen. To this end, she decided to invite to the event held to launch the food policy a specialist from the “Public Catering and Nutrition Market Study Group” (Groupe d’Étude des Marchés de Restauration Collective et Nutrition), which is the official national body that makes nutritional recommendations for public catering establishments in France. By bringing in a national expert on child nutrition issues and drawing on arguments from this national public authority, she reinforced the legitimacy of her approach.

Regarding economic aspects, the deputy mayor pushed for a reduction of food waste in school canteens. Reducing losses and waste in the canteens was seen as a way to offset the extra cost of requiring 20% of organic food in the children’s plates. In order to achieve and publicise a balanced budget while putting better quality food on the canteen menus, the elected official chose a local company, Breizh Phoenix, to experiment ways to assess and reduce waste. This may seem a secondary aspect of the food policy, but it is nevertheless crucial for financial and hence political legitimacy.

The third partnership concerns the agricultural, environmental, and social aspects of Rennes’ food policy. The partnership was established with the administration in charge of the quality of the city’s drinking water, Eau du Bassin Rennais. As part of the school canteen supply programme, a special market was opened up to 2000 local farmers: “those who can sell on this market are those who commit to changing their agricultural practices”.Footnote 17 To benefit from better prices offered by the municipality on this market, farmers had to commit to fulfilling a number of indicators, notably the reduction in the use of chemical inputs to protect groundwater quality. This market is regulated by Eau du Bassin Rennais in close collaboration with the city of Rennes. This innovative legal arrangement allows the city to influence the transformation of neighbouring agricultural landscapes that are actually beyond its legal scope of intervention since these catchment areas are mainly located outside the metropolitan area.

The example of Rennes shows the importance of setting up several alliances, which allowed the deputy mayor and her team to tackle a range of issues and to reinforce the legitimacy of their actions. However, this does not happen without difficulties. Creating new partnerships, especially regarding agricultural issues, can be complicated, as illustrated in the following section.

Opening the local political landscape to new agricultural partners

Agriculture is an emblematic example of the sectorisation of French corporatist policies (Coleman & Chiasson, 2002; Keeler, 1987). These policies saw the rise of a co-determination, also called cogestion by analysts of French agricultural policies, between the French Government and the “agricultural profession”, which mainly refers to the representatives of the majority union FNSEA and their operational branch, the Chambers of Agriculture (Keeler, 1987). At the local scale, cities face a similar form of agricultural corporatism (Thareau, 2011), their main—and often only—interlocutor being the local Chamber of Agriculture. However, the emergence of urban food policies challenges this situation. Cities renegotiate their partnership agreements with the Chambers of Agriculture or even contract with new agricultural partners.

In Montpellier, upon her arrival at the metropolitan council, the Vice-Chair decided to stop all ongoing processes and to rewrite the agreement between the municipality and the Chamber of Agriculture: “When I started, this agreement had for the most part been written by the Chamber of Agriculture itself, which was then both decision maker, prescriber and contractor. We were establishing a new food policy, and its goal was to penetrate the Chamber, not the contrary.”Footnote 18 A new agreement was therefore established between the two entities which redefined the roles of each in the food policy. Furthermore, another agreement was signed for the first time with the InPact network,Footnote 19 an alternative actor in the agricultural sector. For the Vice-Chair, this agreement was a way to recognise the anteriority and the expertise of alternative networks on agricultural and local food and of underlining the plurality of agricultural development models that go beyond productivism.

In Strasbourg, upon her arrival, the deputy mayor went to the local Chamber of Agriculture in order to start an agricultural diagnosis and to initiate the first actions of the policy. She recalls receiving “proper attention”Footnote 20 from the director of the Chamber whose political project was in fact to create partnerships with local governments and to support short food supply chains in order to give agriculture better publicity in the city.Footnote 21 The food policy of Strasbourg was thus developed in close collaboration with the Chamber of Agriculture. In 2008, a first agreement was signed between the metropolitan council and the Chamber of Agriculture. In 2015, the second agreement integrated a new stakeholder into the policy, the local Professional Organisation of Organic and Biodynamic Agriculture (French acronym OPABA), an alternative structure for agricultural development. Since then, OPABA has taken part in the formal food policy decision-making process, in particular in its organic agriculture component. However, including a variety of agricultural stakeholders does not mean equal budgets for each. In Strasbourg, for example, in the 2015 agreement, the Chamber of Agriculture’s budget was six times bigger than the one allocated to OPABA.Footnote 22 Meanwhile, the fact that each partner has the right to sit at the negotiating table marks a shift in the local regulation of agriculture and food, historically monopolised by the Chambers of Agriculture driven by the main conventional farmers’ trade union.

The case of Rennes is a bit different. Although the metropolitan council had signed an agreement with the Chamber of agriculture in 2008,Footnote 23 the city had no formal agreement with any agricultural partner during the studied period. The city managed discussions concerning its food policy in a balanced way between established and alternative structures. Sometimes however, its relationship with the Chamber of Agriculture has been particularly tense due to the environmental focus of the food policy.

Organisational resources: the limits of integrated urban food policies

In this section, we study the organisational obstacles that limit the full operationalisation of the three food policies under scrutiny, and prevent their full deployment. We base our analysis on both the discourse of the interviewees (mainly metropolitan or municipal agents) and a set of institutional documents such as budgets, municipal organisation charts, or municipal council minutes. We underline successively the lack of administrative support and technical expertise; the lack of dedicated staff; and the very small budgets allocated to the three urban food policies.

The lack of an assigned unit and of technical expertise on food systems

In the three case studies, the emergence of a food policy has not led to the creation of a specialised food unit within the urban government. All three food policies were implemented by internal ad hoc and transversal work teams composed of municipal agents from different units (education, economic development, urban planning, etc.). The teams met as and when issues arose. The elected food policy officials did not face difficulty in setting up these teams. On the contrary, voluntary agents were found easily and they were enthusiastic: “You can feel the enthusiasm in the teams, that’s for sure. Because the fact that everyone has to eat is our common foundation. There are many who garden and walk in the countryside too. It is a strength and a very great difficulty at the same time for the day-to-day management of policies”. The first difficulty is the lack of professional skills on cross-sector issues of integrated food policies: “They all express themselves not from their professional position, but based on their personal experience.”Footnote 24 Another common difficulty is that despite their interest in the subject, these municipal agents remained attached to their mission and put their original unit above all else. For example, in Montpellier, the food team was formed of several agents from other units who dedicated around 1/8 of their time to the food policy: “The problem with this ‘1/8 full-time equivalent management’ is that the persons from the Water unit will only express themselves according to their ‘water’ vision, i.e. from the catchment area where they hope to receive money from the water agency. They cannot embrace water and food issues on a metropolitan scale. Meetings of this type do not work.”Footnote 25 Thus, specific unit, training, and skill-building in food system subjects appeared to be one of the biggest challenges facing integrated urban food policies. An interviewee in Montpellier summarised the situation as follows: “there is a political challenge, ideas to defend on food or agriculture, but in my opinion the biggest challenge is mainly administrative and regulatory, it is dealing with the units”.Footnote 26 In the case of Montpellier, most internal tensions originated from the Urban Planning units which, on issues related to agriculture and the installation of new peri-urban farmers, “dragged out the files” or contested very specific points at the end of the validation process, thus weakening the implementation of the city’s agroecological and food policy.

Understaffed food policies

In each case study, a single officer only was recruited to coordinate the meetings of the “food team” and to coordinate actions that were structurally fragmented across different units. During the first years of policy implementation, no other position dedicated to the new food policy was created in any of the three cities. While the recruited coordinators were deeply committed to their mission, they had neither access to structural funds nor to sufficient and trained human resources to carry out their activities. A recurring element in all our interviews was the work overload. According to the food policy coordinator in Montpellier, this is why “enthusiasm is followed by fatigue due to the heavy workload”.Footnote 27 The coordinator in Strasbourg also stressed: “coordination is the main thing, and I only have one pair of hands! It’s not just hard to finance. At some point we must realise that nothing is done without people!”.Footnote 28

The lack of human resources therefore appears to be a structural obstacle to the deployment of public urban food policies. The interviewees attributed this lack of human resources to the fact that “budgetary shortages affect all units”,Footnote 29 referring to the general cuts in local and regional authorities’ budgets that has taken place in France in the last decade. In some cases, however, this lack of human resources is also due to obstruction by some units, which do not welcome the strengthening of a specialised food policy team. This was the case in Montpellier where the lack of formalisation or registration of food policies in municipal government (no specific food unit, no premises, no hierarchy) has led to “institutional bricolage that does not help the empowerment [of this policy]” (Hasnaoui Amri et al., 2020). Moreover, “There were strong obstacles to the creation of a specific unit or the rise of these issues in the metropolis, because when you think creation of a new unit, you think financial cuts for established units. Officials who are well established in their departments do not want to get involved in this new topic, which may disrupt their daily work”.Footnote 30

Underfinanced food policies

Finaly, we must stress that the three food policies under study have no dedicated allocated budgets. They only receive occasional resources to finance some subsidies granted to partners, to organise events, for rehabilitation of a direct trade outlet, or for school catering procurement. The rest of their resources come from the budgets of other internal units: education, land development, public procurement, etc.

The amount of resources available from diverse pre-existing budgets is also particularly low. In Rennes, the total budget for the policy in 2018 was €250,000.Footnote 31 In Strasbourg, the budget for agricultural partnerships in 2013 was around €70,000, to which €30,000 was added for the organisation of events.Footnote 32 Finally, between 2015 and 2017, an annual average of €300,000 was spent on the metropolitan policy in Montpellier.Footnote 33 To illustrate the weakness of these budgets, comparing them to other actions financed by the cities is significant: in the metropolis of Montpellier, a few days of hosting the Tour de France event (national cycling race) in 2016 cost around €350,000Footnote 34 and the following year the city paid the same amount to host the Miss France national beauty pageant for 2 weeks.Footnote 35 In addition, beyond the too small amount of money allocated to the three selected urban food policies, the contingency of the allocated funds is also a major difficulty in the deployment of a long-term integrated food policy.

Discussion

According to Candel and Biesbroek’s multi-dimensional framework, the three urban food policies under study show a high level of policy integration. First, there is general recognition of the cross-cutting nature of the food system problem even if the mainstreaming of food strategy into other policies is limited in all three cases. Second, diverse and multi-partnerships with both the agricultural and socio-economic sectors were created, allowing the elected officials and their teams to tackle a range of food system issues. Finally, a range of innovative goals was set in different cross-cutting policy areas including agriculture (to establish new farmers in the vicinity of the city), economics (to develop short food supply chains), or education (to reach 20% of organic products in school canteens).

However, the implementation of these integrated food policies does not happen without difficulties. Such difficulties narrow their impact, and sometimes might even undermine these policies. One direct consequence of the multiplication of formal partnership agreements and the design of new policy goals is the increase in costs for municipalities who did not finance food policies to the extent of their ambitions and strategic vision. The coordination of multiple partners and instruments mixes is also an energy and time-consuming task in a difficult human resources context. In each of the three metropolitan areas, the absence of a specific food unit was addressed by the creation of an ad hoc, horizontal, and poorly resourced work team. The teams were not sufficiently skilled or trained in the management of food system cross-sector issues. They also faced a huge task of coordination which the few human resources in place struggled to do in addition to their day-to-day work. This appears to be a recurrent structural obstacle. The absence of backing by the city administration, coupled with very low implementation budgets, are additional obstacles. The low degree of formalisation of these policies in municipal or metropolitan services reflects the unequal balance of power around new themes within sectorised local administrations. In sum, the limited human and budgetary resources dedicated to these policies limit their effectiveness and hence their overall impact.

One possible explanation for the lack of organisational resources dedicated to these urban food policies is the weak political powers of the elected officials who vehicle them. Indeed, the three food policies were all initiated by political outsiders, meaning by politicians coming from outside local power structures. Firstly, the three respective elected officials in charge are three women in a still predominantly male political order, in which women remain eternal outsiders (Bard & Pavard, 2013). Secondly, the three women were new to politics: coming from a local protest movement (Montpellier and Strasbourg) or recently engaged in a political party (Rennes) they joined local governments following the 2008 or 2014 municipal elections. All the three claim to be left wing but only the Rennes representative is a member of a political party. Third and finally, they all defend new ideas and new policies for the regulation of food systems. As political outsiders, the three actors had few available political resources and only a weak political network. This may explain the weak institutionalisation of the policies analysed here. In particular, they did not have enough political and institutional resources to either create a specific food policy unit, or to mainstream their strategy into other policies.

Understanding the organisational resources dimension to assess policy integration

In sum, understanding the key role played by the organisational resource dimension in the implementation process of the three urban food policies studied here enables a better understanding of limits to their integration. That is why we argue that the organisational resource dimension (including the existence—or not—of a dedicated unit, human, and financial resources) should be added as a fifth dimension to Candel and Biesbroek’s multi-dimensional framework of policy integration. This is described in Table 2.

Tracking the organisational resources involved (or not) in the setting-up of a policy is thus important to assess its degree of integration. Putting those resources into perspective with the discourses built and diffused around these policies is also a rich source of lessons.

Communication politics—lacking organisational resources does not impede advertising

Another dimension to be added to the picture is the one of communication politics. While recognising the very innovative nature of Rennes’ food policy and its unprecedented partnership with the city’s water quality administration, which are often presented as a success story and a lesson drawing case in food policy expert circles, we must highlight some limits. In particular, we note the relatively small number of direct beneficiaries. By targeting the food served to primary school children, the food policy currently affects only 2% of the daily meals eaten in Rennes. Similarly, only ten farmers were involved in the specific market for the city’s school canteens in 2019.

The Montpellier food policy hardly exceeds these numbers. Aside from events targeting the general public such as the annual Agroecological Transition and Sustainable Food Month, which were widely attended by the local population, actions aimed at the agricultural sector were limited to the establishment of a handful of new farmers on the outskirts of the metropolis, accounting for a total of 9.5 hectares (Hasnaoui Amri et al., 2020). Due to limited human and financial resources available and tensions within the metropolitan government, the establishment of new farmers experienced delays and the final arrangement was not providing them with long-term guarantees (they received only precarious leases and faced difficult operating conditions, including the delayed installation of greenhouses on their farm). Nevertheless, the creation of urban farms has been widely advertised. It is used as an “emblem” for the food policy and is regularly highlighted in the “Mmmag”, the city’s institutional magazine. An agricultural counsellor working on a metropolis installation project was ironic about it: “The metropolis has to install a greenhouse for them, it will double their yields! However, a plastic greenhouse may not be good-looking enough for their Mmmag… [Laughs] Sometimes it’s the Mmmag that makes the political decisions round here!”.Footnote 36 In fact, the food policy was widely publicised in the region, as part of the president of the metropolis’ territorial marketing strategy. As the 2020 municipal elections approached, several “beneficiaries” of this policy regretted that their image and activities were being used to make political gains, while denouncing the limited resources they actually received. For instance, at the Milan Pact public meeting hosted in Montpellier in October 2019, one of the settled farmers publicly addressed the Mayor and his municipal team and claimed the following: “Please stop using farmers to serve your political ambitions. Stop using short food supply chains, organic farming and small producers to make yourselves look good. We are not here to soothe your conscience.”Footnote 37

Similar discrepancies between political communication and concrete actions appear in the food policy of Strasbourg. For example, a 3.5-hectare market gardening park was created in the heart of the city’s future shopping centre. This was presented by the municipality as a way of maintaining agricultural businesses and a way of diversifying peri-urban crops. But the creation of the vast 150-hectare shopping centre itself would lead to the expropriation of 10 farmers who farm 50 hectares of land. The food policy team sees this paradoxical situation as a compromise, arguing that the loss of agricultural land in this particular place makes it possible to safeguard it elsewhere in the city. But, in the end, projections were still forecasting the urbanisation of 1900 hectares of agricultural land in the years to come.

The weakness of human and budgetary resources for urban food policies means their actions focus on a few symbolic interventions that only affect a limited public, but which receive a disproportional amount of publicity. Thus, despite strong media coverage by urban communication units on implemented food policies, which reflects their importance for public opinion, the impact of these actions on the urban food systems remains marginal.

Conclusion

The multidimensional issues surrounding food are a major organisational challenge for cities: “This is such a new field of action! When you talk about roads, people know what you’re talking about, when you talk about culture, we know what you mean, it’s really focused. But when you talk about food: we have to start from scratch!”.Footnote 38 To do so, urban food policy officials call on different levers in different internal units of their municipality. While collaboration between different units means that the many different dimensions related to food are better taken into account, it may also weaken the scope of these policies. Urban food policies do not gather enough human and financial resources within the institutions involved. Because of their “lack of autonomy, authority, and influence” (Coplen & Cuneo, 2015), they struggle to gain acceptance from other urban units and cannot go beyond their marginal impact on urban food systems. However, this does not prevent local governments from communicating actively about food and their own food policies. Such a situation arguably serves the purpose of political communication and legitimisation of the majorities in place, as opposed to fundamentally overhauling urban food systems.

Indeed, to enable more transformative integrated policy approaches, specific food units must be created that are less linked to specific interests and with increased consideration of the multidimensionality of issues. Specific budgets must be assigned to these units for the implementation of public actions, which should match the ambitions of multisectoral food policies, beyond the political communication that is made. Finally, creation of dedicated positions for staff and skill-building in this arena are indispensable. Otherwise, the lack of these organisational resources may jeopardise integrated urban food policies and undermine cities’ capacities to change their local food system.

Notes

In this paper, we use the term “local policies” in the sense of policies undertaken by local authorities.

In February 2022, the Milan Urban Food Policy Pact was signed by 217 cities around the world.

In our view, this difference in the type of governments involved in our 3 case studies (metropolitan councils versus city council) has no major analytical consequences for various reasons. First, none of these governments has any formal competency in the food area specifically. Second, as illustrated further in the course of this paper, the frontier between the city and the metropole is relatively blurred in the three concerned areas, as the city and the metropole share part of their resources, of their administrative staff, elected personal, and political wings.

For information, the government of the metropolitan area of Rennes has signed an integrated policy at the metropolitan level in 2021 (Stratégie “Agriculture et alimentation durables”).

The participant observations were most frequent in Montpellier: a meeting on the selection of candidates for the Urban Farm project (Montpellier, May 20, 2016), follow-up meetings with the candidates selected in 2016, “Matinée Local Lab” (Local Lab morning session) (Montpellier, November 23, 2017), “Sustainable food and agroecological transition regional meetings” (Assises territoriales de la transition agroécologique et de l’alimentation durable”) (Montpellier, May 2, 2019).

Interview with the former deputy mayor of Strasbourg in charge of the food policy, September 19, 2017.

Interview with the former deputy mayor of Strasbourg in charge of the food policy, September 19, 2017.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Interview, former Rennes deputy mayor in charge of the food policy, March 16, 2018.

Interview, former Rennes deputy mayor in charge of the food policy, March 16, 2018.

Editorial of the presentation leaflet for the “Plan Alimentaire Durable de la ville de Rennes 2017–2020” (2017–2020 City of Rennes Food Policy).

Interview with the former Vice-Chair of the Metropolitan Council responsible for agroecology and food, October 16, 2018.

Ibid.

Interview with the former Vice-Chair of the Metropolitan Council responsible for agroecology and food, October 16 2018.

Ibid.

Interview with an “Eau du Bassin Rennais” agent, Rennes, March 22, 2018.

Interview with the former Vice-Chair of the Metropolitan Council responsible for agroecology and food, October 26, 2018.

“Plateforme associative d’Initiatives Pour une Agriculture Citoyenne et Territoriale” (InPact) (associative platform for civic and regional agriculture initiatives) is a network of non-profit organisations working for alternative agriculture development.

Interview with the former Strasbourg deputy mayor in charge of the food policy, September 19, 2017.

Interview with an employee of the Alsace Chamber of Agriculture, May 24, 2018.

In 2015, the Opaba budget for Strasbourg food policy participation was €10,000. The budget of the Chamber of Agriculture for the same year was €60,525.

Darrot et al., « Frises chronologiques de la gouvernance de la transition agricole et alimentaire dans 4 villes de l’Ouest de la France: quels enseignements ?» Communication in XIIIeme journées de la recherche en sciences sociales “L’innovation sociale”, INRA-SFER-CIRAD, December 2019.

Interview with a Montpellier food policy coordinator, September 10, 2018.

Interview with a Metropolitan area of Montpellier employee, April 4, 2017.

Interview with the former Vice-Chair of the Metropolitan Council responsible for agroecology and food, October 26, 2018.

Interview with a Montpellier food policy coordinator, September 10, 2018.

Interview with the former Strasbourg deputy mayor in charge of the food policy, September 19, 2017.

Interview with the former Vice-Chair of the Metropolitan Council responsible for agroecology and food, October 26, 2018.

Interview with a Metropolitan area of Montpellier employee, April 4, 2017.

Interview with the former deputy mayor of Rennes in charge of the food policy, March 16, 2018.

Interview with the Strasbourg City food policy coordinator, November 9, 2017.

Interview with the former Vice-Chair of the Metropolitan Council responsible for agroecology and food, October 26, 2018.

Newspaper article, Montpellier, ville étape de la 103è édition du Tour de France 2016, in Actualités de la ville de Montpellier, May 7, 2016.

“We should pay 350 000 out of the total 600 000 euros invested in the organisation”, said Philipe Saurel, mayor of the city of Montpellier in a newspaper article entitled Miss France, la belle entreprise, Les échos, December 16, 2016.

Interview with a Hérault Chamber of Agriculture employee, October 5, 2017.

Oral intervention of one farmer whose farm was on land owned by the Metropolitan area, Pact of Milan meetings, Montpellier, October 7, 2019.

Interview, with the former Vice-Chair of the Metropolitan Council responsible for agroecology and food, October 16, 2018.

References

Baker, L., & de Zeeuw, H. (2015). Urban food policies and programmes: An overview. In H. Zeeuw & P. Drechsel (Eds.), Cities and Agriculture (pp. 44–73). Routledge.

Bard, C., & Pavard, B. (2013). Femmes outsiders en politique. L’Harmattan.

Benoit, M., & Patsias, C. (2017). Greening the agri-environmental policy by territorial and participative implementation processes? Evidence from two French regions. Journal of Rural Studies, 55, 1–11.

Brand, C. (2017). The french urban food issue emergence. Bollettino della Società Geografica Italiana, 10(13), 65–76.

Brand, C., Bricas, N., Conaré, D., Daviron, B., Debru, J., Michel, L., & Soulard, C.-T. (2019). Designing Urban Food Policies. Concepts and Approaches. Springer.

Candel, J. J. (2020). What’s on the menu? A global assessment of MUFPP signatory cities’ food strategies. Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, 44(7), 919–946.

Candel, J. J., & Biesbroek, R. (2016). Toward a processual understanding of policy integration. Policy Sciences, 49(3), 211–231.

Candel, J. J., & Pereira, L. (2017). Towards integrated food policy: Main challenges and steps ahead. Environmental Science & Policy, 73, 89–92.

Coleman, W. D., & Chiasson, C. (2002). State power, transformative capacity and adapting to globalization: An analysis of French agricultural policy, 1960–2000. Journal of European Public Policy, 9(2), 168–185.

Coplen, A., & Cuneo, M. (2015). Dissolved: Lessons learned from the Portland Multnomah food policy council. Journal of Agriculture, Food Systems, and Community Development, 5, 91–107.

Cretella, A. (2016). Urban food strategies. Exploring definitions and diffusion of European cities’ latest policy trend. Metropolitan Ruralities, 23, 303–321.

Daugbjerg, C., & Swinbank, A. (2012). An introduction to the ‘new’politics of agriculture and food. Policy and Society, 31(4), 259–270.

De Schutter, O., Jacobs, N., & Clément, C. (2020). A ‘Common Food Policy’ for Europe: How governance reforms can spark a shift to healthy diets and sustainable food systems. Food Policy, 96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101849

Dion, S. (1986). La politisation des administrations publiques : Éléments d’analyse stratégique. Canadian Public Administration, 29(1), 95–117.

Drimie, S., & Ruysenaar, S. (2010). The integrated food security strategy of South Africa: An institutional analysis. Agrekon, 49(3), 316–337.

Dubbeling, M., Hoekstra, F., Renting, H., Carey, J., & Wiskerke, J. S. C. (2015). Food on the urban agenda. Urban Agriculture Magazine, 29, 3–4.

Elliott, O. V., & Salamon, L. M. (2002). The tools of government: A guide to the new governance. Oxford University Press.

Fouilleux, E. (2021). The common agricultural policy: An environmental, social and sanitary failure. In H. Zimmermann & A. Dür (Eds.), Key controversies in European integration (pp. 130–137). Springer Nature.

Fouilleux, E., & Michel, L. (2020). Politisation de l’alimentation. Vers un changement de système agroalimentaire ? In E. Fouilleux, & L. Michel (Eds), Quand l’alimentation se fait politique(s) (pp.11–47). Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

Goodman, D., DuPuis, M., & Goodman, M. (2012). Alternative food networks : Knowledge, practice, and politics. Routledge.

Hasnaoui Amri, N., Michel, L., & Soulard, C.-T. (2020). Une politique agroécologique et alimentaire à Montpellier. La transition agroécologique vecteur de compromis politique ? In Fouilleux, È & Michel, L (Eds.), Quand l’alimentation se fait politique(s) (pp. 253–271). Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

Hemphill, L., McGreal, S., Berry, J., & Watson, S. (2006). Leadership, power and multisector urban regeneration partnerships. Urban Studies, 43(1), 59–80.

IPES-Food. (2017). Unravelling the Food–Health Nexus: Addressing practices, political economy, and power relations to build healthier food systems. The Global Alliance for the Future of Food and IPES-Food.

Jarosz, L. (2008). The city in the country : Growing alternative food networks in Metropolitan areas. Journal of Rural Studies, 24(3), 231–244.

Keeler, J. T. S. (1987). The politics of neocorporatism in France: Farmers, the state, and agricultural policy-making in the Fifth Republic. Oxford University Press.

Lang, T., & Barling, D. (2013). Nutrition and sustainability: An emerging food policy discourse. Proceedings of the Nutrition Society, 72(1), 1–12.

Lang, T., & Barling, D. (2012). Food security and food sustainability: Reformulating the debate. The Geographical Journal, 178(4), 313–326.

Mansfield, B., & Mendes, W. (2013). Municipal food strategies and integrated approaches to urban agriculture: Exploring three cases from the global north. International Planning Studies, 18(1), 37–60.

Mendes, W. (2008). Implementing social and environmental policies in cities: The case of food policy in Vancouver Canada. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 32, 942–967. Blackwell publishing ltd.

Michel, L., & Soulard, C.-T. (2017). Comment s’élabore une gouvernance alimentaire urbaine? Le cas de Montpellier Méditerranée Métropole. In C. Brand, N. Bricas, D. Conaré, B. Daviron, J. Debru, L. Michel, & C.-T. Soulard (Eds.), Construire des politiques alimentaires urbaines: Concepts et démarches (pp. 137–150). Quae.

Moragues-Faus, A., & Morgan, K. (2015). Reframing the foodscape: The emergent world of urban food policy. Environment and Planning a: Economy and Space, 47(7), 1558–1573.

Morgan, K. (2015). Nourishing the city The rise of the urban food question in the Global North. Urban Studies, 52(8), 1379–1394.

Morgan, K., & Sonnino, R. (2010). The urban foodscape: World cities and the new food equation. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3, 209–224.

Mumenthaler, C., Schweizer, R., & Cavin, J. S. (2020). Food sovereignty: A nirvana concept for Swiss urban agriculture? In A. Thornton (Ed.), Urban Food Democracy and Governance in North and South (pp. 87–100). Palgrave Macmillan.

Neff, R. A., Merrigan, K., & Wallinga, D. (2015). A food systems approach to healthy food and agriculture policy. Health Affairs, 34(11), 1908–1915.

Okner, T. (2017). The role of normative frameworks in municipal urban agriculture policy : Three case studies from the United States. Natures Sciences Sociétés, 25(1), 70–79.

Page, E. C., & Jenkins, B. (2005). Policy bureaucracy: Government with a cast of thousands. Oxford University Press.

Pahun, J. (2020). Manger local: Canalisation des débats politiques sur l’alimentation en régions. In E. Fouilleux & L. Michel (Eds.), Quand l’alimentation se fait politique(s) (pp. 181–198). Presses Universitaires de Rennes.

Peters, B. G. (2002). The changing nature of public administration: From easy answers to hard questions. Asian Journal of Public Administration, 24(2), 153–183.

Pothukuchi, K., & Kaufman, J. L. (2000). The food system: A stranger to the planning field. Journal of the American Planning Association, 66(2), 113–124.

Rocha, C., & Lessa, I. (2009). Urban governance for food security: The alternative food system in Belo Horizonte Brazil. Int Plan Stud, 14(4), 389–400.

Santo, R., & Moragues-Faus, A. (2019). Towards a trans-local food governance: Exploring the transformative capacity of food policy assemblages in the US and UK. Geoforum, 98, 75–87.

Selznick, P. (1980). TVA and the grass roots: A study of politics and organization. University of California Press.

Sibbing, L., & Candel, J. (2021). Realizing urban food policy: A discursive institutionalist analysis of Ede municipality. Food Security, 13, 571–582.

Sibbing, L., Candel, J., & Termeer, K. (2021). A comparative assessment of local municipal food policy integration in the Netherlands. International Planning Studies, 26(1), 56–69.

Skocpol, T., & Finegold, K. (1982). State capacity and economic intervention in the early New Deal. Political Science Quarterly, 97(2), 255–278.

Sonnino, R. (2017). The cultural dynamics of urban food governance. City, Culture and Society., 16, 12–17.

Steel, C. (2013). Hungry City : How Food Shapes Our Lives. Vintage.

Sonnino, R., Tegoni, C. L., & De Cunto, A. (2019). The challenge of systemic food change: Insights from cities. Cities, 85, 110–116.

Southern, R. (2002). Understanding multi-sectoral regeneration partnerships as a form of local governance. Local Government Studies, 28(2), 16–32.

Svara, J. H. (1985). Dichotomy and duality: Reconceptualizing the relationship between policy and administration in council-manager cities. Public administration review, 45(1), 221–232.

Termeer, C. J. A. M., Drimie, S., Ingram, J., Pereira, L., & Whittingham, M. J. (2018). A diagnostic framework for food system governance arrangements: The case of South Africa. NJAS. Wageningen Journal of Life Sciences, 84, 85–93.

Thareau, B. (2011). Réguler l’accès à la terre, la réinvention locale du corporatisme agricole. Université de Nanterre-Paris X.

Trouvé, A., Berriet-Solliec, M., & Déprés, C. (2007). Charting and theorising the territorialisation of agricultural policy. Journal of Rural Studies, 23(4), 443–452.

Funding

This work was supported by ANR fundings (Agence nationale de la recherche) through the IDAE project (Institutionalizing agroecologies), ANR-15-CE21-0006–01.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

In this paper, the conceptualization, the methodology, the formal analysis, and the validation process are the fruit of the collaboration between the two authors. The investigation part that is the conduction of the research process on the ground in the three urban areas, specifically data/evidence collection and data curation, has been operated by JP in the frame of her PhD thesis, which was conducted under EF supervision. JP and EF wrote collectively the manuscript. The text was English-edited by Annie-Rose Harrison-Dunn and Daphne Goodfellow. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript. The two authors warmly thank the two reviewers for their stimulating comments and advices, which considerably helped them to improve their manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Not relevant for this article. There were no mandatory procedures in this field in France at the time of the project. No personal data was collected in our research.

Consent to participate

Informed consent was obtained from all interviewees. No names or any other identifying information was used in publications resulting from this research.

Consent for publication

All authors agreed with the final content of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pahun, J., Fouilleux, E. Organisational troubles in policy integration. French local food policies in the making. Rev Agric Food Environ Stud 103, 247–269 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s41130-022-00174-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s41130-022-00174-2