Abstract

Human rights due diligence is today a key aspect of the international, regional and national debates about corporate accountability for human rights abuse. It is a process by which businesses are expected to assess actual and potential human rights impacts, integrate and act upon the findings, track the responses, and communicate how those impacts are addressed. Yet there is little research as to how effective human rights due diligence is and whether its aim to prevent business activities which have adverse impacts on human rights, has been achieved in state and business practices. HRDD is now at the crossroads as it begins to become part of legislation, which will firmly test its potential to contribute substantively to the prevention of corporate human rights abuses. Drawing on developments in law and empirical research, this article examines the effectiveness of human rights due diligence as a means to prevent business activities which have adverse impacts on human rights, in relation to the actions of states, business and rightsholders.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Over the last decade, human rights due diligence (‘HRDD’) has emerged as a key mechanism to address human rights abuses by business but there remain questions as to the extent of its effectiveness in preventing such harms. In the rapidly developing area of business and human rights, the notion of prevention is a key element and relates to the prevention of the activities of businesses around the world from causing, contributing to or being linked to adverse human rights impacts.Footnote 1 Business related human rights harms may take many forms and significant attention is often focused on global supply chains where too often these chains prize low cost and fast production over respect for basic labour rights.Footnote 2 However, no sector is immune and business may both directly and indirectly, and deliberately and inadvertently be involved in human rights abuses.

In this context, the relevant international standards provide that both states and businesses should put in place effective methods to prevent actual and potential adverse human rights impacts and to provide effective remedies to those affected.Footnote 3 These standards set out that states have an international legal obligation to protect human rights in this regard, while businesses have a responsibility to respect human rights. The business responsibility to respect human rights is considered to be a socially expected responsibility, and it remains a largely voluntary responsibility if there is no regulatory requirement.Footnote 4

The United Nations Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights 2011 (‘UNGPs’) is the key international document on business and human rights and incorporates the concept of HRDD in its framework. Although it is not legally binding, it is considered as the ‘global authoritative standard on business and human rights’,Footnote 5 and has influenced other international standards (discussed below) and has also been considered in national courts.Footnote 6 A state’s international legal obligations in relation to business activities is set out in its first Guiding Principle:

States must protect against human rights abuse within their territory and/or jurisdiction by third parties, including business enterprises. This requires taking appropriate steps to prevent, investigate, punish and redress such abuse through effective policies, legislation, regulations and adjudication.

Prevention is set out as the first action which states should take. The means to take this action is by developing a range of policies, legislation, regulations and adjudication. Guiding Principle 1 is considered to reflect customary international law.Footnote 7

In order to determine what type of preventative actions is required by a state to be effective, the article will consider the prevention responsibilities of business, as the two are inextricably linked. Indeed, a Dutch court has noted:

The responsibility of business enterprises to respect human rights, as formulated in the UNGP, is a global standard of expected conduct for all business enterprises wherever they operate. It exists independently of States’ abilities and/or willingness to fulfil their own human rights obligations, and does not diminish those obligations. And it exists over and above compliance with national laws and regulations protecting human rights. Therefore, it is not enough for companies to monitor developments and follow the measures states take; they have an individual responsibility.Footnote 8

This article will explore prevention within the context of the business and human rights regulatory framework. It will do so by clarifying the key terminology of HRDD, and how it has been applied to date in legislation by states and in courts. It will then consider how to assess effectiveness in this context. In doing so it will consider the relevance of the developments in other areas of law, noting that business and human rights law itself draws from a wide area of legal and non-legal disciplines, such as public and private international law, corporate law, tort and contract/obligations law, anti-bribery law, management studies and business ethics.

2 Prevention Under Business and Human Rights Law

2.1 Human Rights Due Diligence

HRDD was crafted in the UNGPs as the method by which businesses are to prevent adverse human rights impacts and also for business to mitigate, and where relevant, to remediate these impacts. The intention of this method was to ensure that businesses acted in such a way that, by their due diligence, their activities did not have adverse human rights impacts on rightsholders.Footnote 9 The key drafter of the UNGPs, John Ruggie, defined HRDD as ‘a comprehensive, proactive attempt to uncover human rights risks, actual and potential, over the entire life cycle of a project or business activity, with the aim of avoiding and mitigating those risks’.Footnote 10

HRDD began in the UNGPs and has since been adopted by subsequent international documents on this area, as well as in national legislation (see below). The OECD’s Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises 2011 (‘OECD Guidelines’),Footnote 11 the International Labour Organisation’s Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy 2017,Footnote 12 the International Finance Corporation’s Performance Standards 2012Footnote 13 and the Equator Principles 2013,Footnote 14 were all revised to incorporate HRDD (as well as most of the other core elements of the UNGPs). These form the main international standards in this area. Indeed, the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights notes that ‘since the endorsement of the Guiding Principles by the Human Rights Council in 2011, corporate human rights due diligence has become a norm of expected conduct’.Footnote 15

Guiding Principle 17 of the UNGPs provides the clearest explanation of what HRDD means:

The process [of HRDD] should include assessing actual and potential human rights impacts, integrating and acting upon the findings, tracking responses, and communicating how impacts are addressed. Human rights due diligence:

(a) Should cover adverse human rights impacts that the business enterprise may cause or contribute to through its own activities, or which may be directly linked to its operations, products or services by its business relationships;

(b) Will vary in complexity with the size of the business enterprise, the risk of severe human rights impacts, and the nature and context of its operations;

(c) Should be ongoing, recognizing that the human rights risks may change over time as the business enterprise’s operations and operating context evolve.

This indicates that HRDD is a process, or rather a ‘bundle of interrelated processes’,Footnote 16 through which businesses can identify, prevent, mitigate and account for their actual and potential adverse human rights impacts. The use of HRDD in the UNGPs appears to be an innovative and deliberate tactic by the drafters, as ‘due diligence’ is a term which is familiar to business people, human rights people and states, though with different understandings for each.Footnote 17 Indeed, while ‘due diligence’ has been used in some national instruments prior to the UNGPs, and it ‘resonates with existing standards of duty of care in tort law and comparable concepts in civil law’,Footnote 18 it had not been used in relation to human rights impacts and business activities until its use in the UNGPs.

The Interpretive Guide to the UNGPs provided by the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (‘OHCHR’) defines HRDD is ‘an ongoing management process that a reasonable and prudent enterprise needs to undertake, in light of its circumstances (including sector, operating context, size and similar factors) to meet its responsibility to respect human rights’.Footnote 19 This seems to assume a management risk based approach to HRDD, which is arguably deferential to business providing it with the flexibility to determine both how it identifies and addresses risk. Some suggest that a problem-based approach would provide a better understanding of how HRDD operates.Footnote 20 Indeed that lack of distinguishing HRDD as a management risk process from it being a standard of conduct can lead to the false assumption that merely by implementing HRDD a business meets its responsibility to respect human rights and ‘managing’ risk produces a solution for those impacted, as is discussed below.

A business must also respect human rights at all times across all its activities, including those it does itself, including by its subsidiaries, and those activities of its business relationships.Footnote 21 This distinguishes HRDD from a one-off process and from being solely about what the business itself does. Thus this responsibility on business stretches across supply chains, whether or not it is a contractual relationship, and to all rightsholders, including workers, consumers and local communities. The OECD has also published a number of Responsible Business Conduct Guidance documents in relation to particular sectors, which apply HRDD to human rights impacts related to conflict, labour rights, bribery and corruption, disclosure and consumer interests, and in the supply chain more generally.Footnote 22

The UNGPs make clear that ‘[b]ecause business enterprises can have an impact on virtually the entire spectrum of internationally recognized human rights, their responsibility to respect [human rights] applies to all such rights’.Footnote 23 However, the UNGPs did not refer to environmental rights. Nevertheless, the OECD Guidelines do extend HRDD to environmental protectionFootnote 24 as does the IFC Performance Standards and the Equator Principles, and environmental rights are now becoming generally included in due diligence in national legislation, at least across the European Union (‘EU’).Footnote 25 HRDD has also more recently been noted as extending to climate change impacts.Footnote 26

The sense to which HRDD is primarily about preventionFootnote 27 is seen in the latest draft of a treaty on business and human rights. This draft arises out of a UN Human Rights Council resolution establishing an open-ended intergovernmental working group (‘OEIGWG’) on transnational corporations and other business enterprises with respect to human rights whose mandate is to ‘elaborate an international legally binding instrument to regulate, in international human rights law, the activities of transnational corporations and other business enterprises’.Footnote 28 The latest draft, released in August 2021, has an Article headed ‘Prevention’.Footnote 29 That draft Article sets out a range of state obligations in relation to business activities to prevent human rights abuses, with HRDD being at the core of the means to do this:

6.2 States Parties shall take appropriate legal and policy measures to ensure that business enterprises […] respect internationally recognized human rights and prevent and mitigate human rights abuses throughout their business activities and relationships.

6.3 For that purpose, States Parties shall require business enterprises to undertake human rights due diligence.Footnote 30

While the Article also includes the other key aspects of HRDD, such as identification, mitigation and accounting, the focus remains on prevention.

Accordingly, a key aspect of prevention in business and human rights concerns the expectation that businesses will undertake HRDD in order to prevent potential human rights impacts—including environmental and climate change damage—from their own activities and those of their business relationships. This expectation is linked directly to the international legal obligation on states to act to prevent human rights abuse by businesses within their territory or jurisdiction, so that states should pass effective legislation on businesses requiring them to undertake HRDD. This is partly because HRDD, as a means of prevention, is not necessarily directly linked to legal liability.Footnote 31

2.2 Actions by States to Prevent Human Rights Abuse by Business

There are currently four pieces of national legislation which specifically seek to apply aspects of the UNGPs and OECD Guidelines about HRDD. These are the French Duty of Vigilance Act 2017 (Devoir de Vigilance Loi), the Dutch Child Labour Due Diligence Act 2019, the German Corporate Due Diligence in Supply Chains Act 2021 and the Norwegian Transparency Act 2021.Footnote 32 In addition, there are other pieces of national and sub-national legislation which are relevant to HRDD and were passed after the UNGPs, such as the Australian Illegal Logging Prohibition Act 2012, the UK Modern Slavery Act 2015 and the Australian Modern Slavery Act 2018Footnote 33 as well as some legislation in the Global South.Footnote 34 The EU also passed the EU Timber Regulation 2010Footnote 35 and the EU Conflict Minerals Regulation 2014,Footnote 36 both of which require HRDD, and civil society in many states have proposed instruments which will have ‘mandatory human rights due diligence’ at their centre.Footnote 37

In addition, the European Justice Commissioner has announced that the European Commission would introduce draft legislation in 2021 requiring mandatory human rights (including environmental) due diligence on businesses across all EU Member States.Footnote 38 Related to this process, the European Parliament (‘EP’) has recently produced proposed legislation in this area,Footnote 39 which was overwhelmingly approved by the EP and, while not binding on the EC, it may be potentially indicative of future EU legislation.

Related to these legislative developments, there have been an increasing number of cases before domestic courts (which are state organs for the purposes of international law) which have extended the obligations on businesses in this area. These cases have shown that a parent company does have a duty of care in relation to the activities of their foreign subsidiaries which have adverse human rights and environmental impacts (e.g. Vedanta v Lungowe and Okpabi v Shell in the UKFootnote 40), for which they need to provide a remedy (Four Nigerian Farmers v Shell in the NetherlandsFootnote 41); and that companies can have a duty of care where it is clearly foreseeable that a human rights harm by a third party will be the consequence of their actions (Sanda v PTTEP Australasia (Ashmore Cartier) Pty Ltd (No. 7) in Australia,Footnote 42 and Begum v Maran [2021] in the UKFootnote 43). In Canada, it was held in Nevsun Resources Ltd v ArayaFootnote 44 that customary international law’s prohibitions against slavery, forced labour, crimes against humanity and cruel, inhuman and degrading treatment could be applicable directly to a business.Footnote 45

There have been instances where the domestic courts have gone beyond the UNGPs to apply duties on businesses in relation to human rights impacts of business which emphasize the need to engage in prevention and draw on international standard to reinforce such arguments. In Milieudefensie v Royal Dutch ShellFootnote 46 before the courts of the Netherlands, they concluded that ‘The UNGP constitute an authoritative and internationally endorsed “soft law” instrument’ and as such ‘are suitable as a guideline in the interpretation of the unwritten standard of care’.Footnote 47

What can be derived from these developments, is that there is a strong momentum towards more national and regional legislation on mandatory HRDD, at least within parts of the Global North. This is, at the moment, somewhat piecemeal in terms of the scope of human rights and businesses covered, and in consequences. Yet it does show that some states are acting in ways to uphold their international legal obligations to prevent businesses having adverse human rights impacts. Similarly through courts in some states, there is an increasing awareness that businesses have some obligations in relation to their activities which have impacts on human rights, the environment and climate change.

3 Effectiveness of HRDD

This article seeks to examine how effective is the element of prevention in the area of business and human rights. Effectiveness in the application of international legal principles has been considered by Charles de Visscher, a former judge of the International Court of Justice (‘ICJ’):

The notion of effectiveness touches on that of reality in the relationship between fact and law. The jurist looks to the real world in order to ascertain the weight of support that attaches to what is objectively valid. In the field of international law, he resorts to that reality either to find in it the justification for an established order, or for the purpose of advocating a new formulation of the law or a principle for the solution of a conflict of legal claims.Footnote 48

Hence it is the extent to which the aims of the international legal principle are found in the outcomes attained. In this instance it is whether the aim for the prevention of business activities which have adverse impacts on human rights has been achieved in state and business practices.

In considering the actions taken by states to implement their obligation to prevent business activities from impacting on human rights, research on the effectiveness of such legislation has indicated that—while there is a spectrum of views—it seems to have three main aspects: first, effectiveness of the law to achieve compliance with the express requirements of the law; second, effectiveness of the law to result in changes in corporate behaviour; and third, effectiveness of the law to prevent the unwanted outcome.Footnote 49 This approach still has real difficulties, as shown in a study on the effectiveness of the UK Modern Slavery Act, where the report concluded: ‘This kind of evidence [of effectiveness] is notoriously difficult to obtain because, even where there is sufficient evidence of a decrease in modern slavery incidences, it is rarely possible to [find] without consistent and intentional monitoring through continuous inspections, and deep understanding of the organisations’ structure and business model’.Footnote 50 It also fails explicitly to take into account effectiveness from the perspective of rights holders who have been or are likely to be impacted by the business’ activities.

In considering effectiveness, it must be acknowledged that HRDD was only adopted into the business and human rights framework in 2011, and implementation has been sporadic, so any interrogation of effectiveness must be considered within that very limited timeline.Footnote 51 Thus our analysis on effectiveness of HRDD as a means of prevention is about the extent to which prevention through HRDD has pushed the development of new practices by states and businesses so as to improve responsiveness by them of dealing with adverse human rights impacts of business activities. While this is a co-regulatory model of state and business responding to HRDD, the state should assume the main preventative role so that the decision on compliance is not left to the discretion of business. Our analysis is in three parts and analyses the extent to which HRDD has been effectively adopted and applied by business; state actions have been effective in ensuring that businesses undertake effective HRDD; and HRDD has been effective in facilitating the participation of rights holders in the process.

3.1 HRDD Effectiveness and Business

The starting point here is the extent to which businesses support the idea of HRDD, as HRDD (whether voluntary or mandatory) seeks to draw a compromise between strong regulation of business on the one hand and deregulation on the other, by optimising a mix of public and private regulation to achieve compliance.Footnote 52 For this co-regulatory model to be effective, HRDD must not only be supported by business but also implemented by them, for this co-regulatory model to be effective. The role of the state is critical, but it essentially acts as the orchestrator of private actors to encourage (and sometimes mandate) compliance.

There is emerging empirical evidence to assist with this analysis, and we highlight some of these developments below. Research conducted on HRDD requirements through the supply chain, commissioned by the European Commission, showed that a large majority (over 75%) of the 350 business respondents to a survey indicated that any EU-level regulation on mandatory HRDD would benefit business through providing a ‘single, harmonised EU-level standard (as opposed to a mosaic of different measures at domestic and industry level)’.Footnote 53 It also showed that a core reason for this corporate support for legislation on HRDD is that it could provide legal certainty, coherence and consistency, and what is often called a ‘level playing field’.Footnote 54 Interestingly, this research also showed that the majority of businesses considered that such regulation would improve or facilitate leverage with third parties by introducing a non-negotiable standard, without reducing competitiveness or innovation. These findings have been backed by other research,Footnote 55 and by the levels of support by businesses for some of the HRDD legislative proposals across various states,Footnote 56 though this is often contingent on the levels of liability being proposed,Footnote 57 and is by no means universal.

This general support by the business community must then be tested by the reality of action. Three empirical research studies have examined the reality of business responses to implementing HRDD in practice. First, in research carried out in 2018 (seven years after the UNGPs) of over 350 businesses,Footnote 58 37 percent were undertaking dedicated HRDD, though of these, only half of them covered the entire value chain of a business. Another 34 percent undertake due diligence only in selected areas, such as health and safety, labour, non-discrimination and equality, environmental, land rights and indigenous communities. Of the largest businesses, only 2.5 percent did not undertake any form of due diligence. However there remains a significant number of businesses which are not undertaking substantive HRDD as expected under the UNGPs.

Second, since 2017 the Corporate Human Rights Benchmark (‘CHRB’), has produced research which aims to ‘provid[e] a comparative snapshot year-on-year of the largest companies on the planet, looking at the policies, processes, and practices they have in place to systematise their human rights approach and how they respond to serious allegations’.Footnote 59 This focuses on five sectors: agricultural products, apparel, automotive manufacturing, extractives and ICT manufacturing, incorporating 229 businesses. While there have been some significant improvements by individual businesses and in some sectors, and some very high outcomes for some businesses, the overall conclusion in the 2020 CHRB was that ‘only a minority of companies demonstrate the willingness and commitment to take human rights seriously… [and] the disconnect between commitments and processes on the one hand and actual performance and results on the other’.Footnote 60 Even more stark were the outcomes in terms of HRDD, where a significant number (in some sectors over 66%) of businesses scored 0% in having and operating a HRDD process, and ‘the lowest areas of improvement [over the 4 years] relate to the human rights due diligence process’.Footnote 61 This was still the situation even after investors intervened demonstrating a deeply entrenched resistance by many businesses in those sectors to making HRDD a reality in their operations:

In March 2020, a group of 176 international investors representing over USD 4.5 trillion in assets under management sent a letter to the 95 companies that failed to score any points on the human rights due diligence indicators in the 2019 CHRB assessment, calling for urgent improvement. Of those 95 companies, only 16 have improved on human rights due diligence this year, with 79 still failing to score any points on the related indicators. Of companies assessed for the first time in 2020, 70% also failed to score any points in this area of the assessment.Footnote 62

The extent to which investors can play a key role in using their leverageFootnote 63 to develop and implement HRDD as a preventative tool for addressing business impacts on human rights remains an open question. However, investors, as shareholders of corporations, can, in effect, become the ‘regulators’ of business with respect to human rights. A report by the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights in 2021 noted that ‘investors are expected to carry out human rights due diligence during the pre-investment phase as well as during the life of their investment in order to know how their investment activities are connected with human rights risks and show how they take steps to address these risks’.Footnote 64 The practice of investors taking into consideration non-financial factors that include human rights is one that has been expanding since the 1960s and continues to do so.Footnote 65 The consideration of human rights, is generally classified as a ‘non-financial’ issue, commonly framed more broadly as Environmental, Social and Governance (‘ESG’) or sustainability considerations. Investors are important not only because of their regulatory role but because the financial sector, provides the capital for the business activity that takes place in the global economy.Footnote 66 In that role, this sector can influence the conditions that provide for the enjoyment of human rights or, conversely, conditions in which human rights might be adversely impacted and even prevented.Footnote 67

However, while investor engagement on HRDD is critical, non-financial reporting which informs the identification and management of risks, has been described as incomplete, unreliable and of poor quality.Footnote 68 There is no generally accepted definition of what the ‘S’ in the ESG should incorporate or how to measure such issues and so the information that could inform the HRDD process may be of limited utility.Footnote 69 Part of the problem here is that for some businesses that investors are assessing, HRDD is more about the process than the practice and there is a myopic focus on disclosure as an end in itself rather than as part of a holistic approach to HRDD.Footnote 70 Reporting is simply the final step in the process of identifying, assessing and addressing human rights risks, and tracking the effectiveness of those responses. For reporting to be both useful and legitimate, it should be based on effective HRDD that has both a preventative and remedial framework. Disclosure alone should not be mistaken for HRDD and while ‘sustainability reporting is assumed to drive organisational change within companies’,Footnote 71 further research is needed on the positive link between corporate reporting and corresponding systemic change to corporate practices that would prevent harms occurring in the first place.Footnote 72 A 2020 report examining the modern slavery statements of 79 asset management firms in the UK, acknowledged the potential leverage investors may have to advocate for stronger action in encouraging companies to go ‘beyond policies and commitments to providing evidence of due diligence measures but found that less than one-third conduct some form of due diligence on human rights in their portfolio companies.Footnote 73

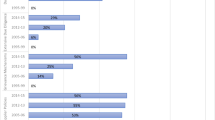

Third, in 2016 the German government issued its National Action Plan (‘NAP’) to implement the UNGPs.Footnote 74 As part of this NAP the German government indicated that it did not wish to introduce legislation on HRDD if at least half of all businesses in Germany with more than 500 employees had adequately integrated the core elements of HRDD into their business processes in a verifiable manner by 2020. The survey in 2020 found that only 13–17 percent of businesses were able to document that they were adequately meeting the NAP requirements on HRDD.Footnote 75 As a consequence, the German government introduced legislation in 2021, the German Corporate Due Diligence in Supply Chains Act 2021, to remedy this lack of action by businesses.

What all this research demonstrates is that HRDD, while an emerging concept, is still in an embryonic state of development and its potential to act as an effectiveness mechanism to prevent corporate human rights abuses remains only a possibility at present. The ability to assess the current state of HRDD practice is heavily dependent upon the public disclosures made by businesses, which in turn are dependent on the veracity of the information business is relying on to formulate such reporting. In terms of the information gathered to support HRDD disclosures, empirical research suggests that supplier audit is the one of the most prominent methods employed to identify human rights risks.Footnote 76 This is unsurprising given how the prevalence of social (or ethical) compliance auditing has increased as a tool to address exploitative labour conditions, particularly those evident in supply chains.Footnote 77 Social auditing is a process by which a company verifies supplier compliance with human rights standards. Social auditing is contemplated by the UNGPs and other international standards discussed above, yet it is ascribed a reasonably limited role and is referred to ‘solely in the context of tracking, noting that it may be one of an array of tools used to assess the effectiveness of a company’s response to its human rights impacts’.Footnote 78 Indeed, ‘an audit is designed to focus on information representing symptoms, rather than the root cause of the problems’Footnote 79 and thus, while it may be a method to gather information for HRDD, it should not be the main means to implement HRDD. HRDD is fundamentally different from social auditing in its approach, scope, and ambition. Hence, the ongoing reliance on social auditing by businesses reflects a very limited vision of HRDD and may result in cosmetic or self-legitimating compliance-oriented responses by business to address and reduce the potential for harms.Footnote 80 In addition, there is now a growing body of evidence indicating that social auditing is, in and of itself, an ineffective tool for achieving meaningful and consistent human rights improvements.Footnote 81 New laws and regulations that mandate HRDD should not equate social audits with HRDD or see them as a substitute.Footnote 82

While this discussion shows a disappointing picture of compliance by businesses with HRDD, there are some companies which are working to undertake effective HRDD. For example, Unilever and Eni both scored 25 out of 26 in the CHRB 2020, and Unilever has announced that it will pay a living wage by 2030 to all those working in directly supplying goods and services to Unilever.Footnote 83 Also, some businesses have incorporated independent human rights evaluations in their human rights assessment,Footnote 84 and HRDD is a core element of some industry initiatives.Footnote 85

There is, though, a large gap between businesses which are supportive of HRDD and those which put HRDD into action in a substantive way. It is evident, that after 10 years of implementation of HRDD, its effectiveness in business practice remains limited. As a means of prevention of human rights abuses by business, the essentially voluntary nature of HRDD and the current flexibility it offers business in determining its scope, has meant that there is still some distance to go before HRDD may be effective. Its potential reliance on social auditing to gather information to identify and assess potential risks is also problematic. Thus, there is increasing pressure on states to implement legislation requiring businesses to undertake HRDD that is both substantive and sustainable.

3.2 HRDD Effectiveness and States

It has been shown above how there is a rapidly increasing number of state, regional and international regulation which require or encourage businesses to undertake HRDD. It is beyond this paper to provide detailed reviews of each of these pieces of legislation, yet it is clear that they vary widely in both their scope and consequences, which may impact their effectiveness. For example, some are intended to apply to all human rights (e.g. French Duty of Vigilance Act), while others are limited to certain human rights (e.g. child labour or modern slavery), though most do expressly include environmental impacts. Some extend to all businesses operating in a state (e.g. the Dutch Child Labour Due Diligence Act), while most only extend to those businesses domiciled in the state and with a threshold in terms of number of employees (e.g. German Corporate Due Diligence in Supply Chains Act) or turnover (e.g. UK and Australian Modern Slavery Acts). Some have a focus on consumer protection (e.g. the Dutch Child Labour Due Diligence Act) or freedom of information (e.g. Norwegian Transparency Act), and some include civil liability provisions (e.g. French Duty of Vigilance Act) and administrative and criminal liability (e.g. the Dutch Child Labour Due Diligence Act), though others seem to have no effective liability linked to specific HRDD requirements (e.g. German Corporate Due Diligence in Supply Chains Act, UK Modern Slavery Act, Australian Modern Slavery Act).

The issues of liability and enforcement are significant as HRDD by itself does not include liability or enforcement, and reporting or transparency without liability and enforcement is rarely effective as a means of changing conduct.Footnote 86 The reliance on self-regulation in the business and human rights field has been long been criticised.Footnote 87 The UNGPs polycentric governance or co-governance approach to regulation also has limitations, which are becoming increasingly apparent in some of the new reporting laws that have been more recently developed. Indeed,

[…] one key assumption in this co-governance approach is that compliance will not only facilitate nonstate stakeholders holding firms to account but will also invariably open the corporation to public policy imperatives […] Transparency about human rights in global supply chains relies on creating a culture of continuous improvement within the organisation and across value chain […] [However] there is reason to doubt that the MSA’s [Australian Modern Slavery Act] assumed internalisation, transformation and embedding will eventuate.Footnote 88

This means that, without liability and enforcement, there is a heavy burden on civil society to act on the limited information provided by business reporting on their human rights impacts. Reliance by the state on enforcement actors such as civil society groups to ensure HRDD implementation will be insufficient given their limited resources. The ability of civil society to act as a regulator is also restrained by the generally restrictive approach of national courts to claims against businesses for actions by their foreign based subsidiaries or in their supply chain, due to the notion of ‘corporate veil’ or separate corporate legal personality or other legal reasons, as noted above.Footnote 89 In addition, there is a risk that legislation which simply requires a ‘tick box’ approach by businesses, such as the EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive 2014, which requires all publicly listed businesses to report on, amongst other things, human rights and environmental issues, with no enforcement requirements, will have limited impact.Footnote 90 Therefore, it is important to balance corporate social disclosures and the regulatory participation of non-state based actors such as civil society, with complementary state enforcement mechanisms for effective HRDD implementation.

Where the legislation has introduced civil, administrative and/or criminal liability, these are still to be tested as to their effectiveness. A key feature of imposing a stronger enforcement framework is that it acts not simply as a deterrent but also works to incentivise compliance of HRDD by business.Footnote 91 This is particularly powerful in situations where the optimal approach to regulation is unknown,Footnote 92 either because the activity being regulated is a new phenomenon or because the environment in which regulation must occur is complex, dynamic and continually evolving, such as with HRDD. There are lessons to be learned here from other fields, including global regulatory efforts to tackle bribery in international business transactions,Footnote 93 as ‘corruption is the grease that enables many forms of crime’Footnote 94 including human rights violations. Efforts to combat it have relied primarily on a criminal law framework to address the issue and also incorporate elements of HRDD (though not defined as such) backed by strong regulatory penalties for non-compliance.Footnote 95 For example, the UK Bribery Act 2010 incorporates an adequate procedures defence that allows companies to implement mechanisms and policies aimed at preventing harms from occurring (and places the burden of proof on the accused organisation if such adequate procedures are found to be absent, in which case, significant penalties can be applied).Footnote 96 While recognising the need for HRDD in the business and human rights field, to allow for innovation and flexibility from business in developing compliance systems and strategies to prevent human rights abuses, there is also a need to ensure that there is a state mandated enforcement framework that is adequately monitored and resourced that both incentivises business to act and penalises them if they do not, such as that offered in the UK Bribery Act.

There is always a risk that the liability and enforcement imposed is so limited that they do not operate to prevent business activities which adversely impact on human rights or even change the behaviour of business. Indeed, as Gabriella Quijano and Carlos Lopez conclude after an insightful review of legislative proposals on HRDD in the 10 years since the UNGPs:

[A]ll those more or less directly involved in processes to bring about new laws must watch out for and ensure the following two critical risks are avoided. Firstly, the risk of creating the appearance of progress with hollow HRDD laws that, while doing little to change the status quo in practice, will effectively bring legislative efforts to an end, at least for the foreseeable future. Secondly, the risk of inadvertently providing companies with a tool that they hitherto did not have to show respect for human rights and rebut charges of liability with little bearing on effective respect for human rights on the ground.Footnote 97

While there is clearly an international legal obligation on states to act to prevent abuses of human rights by business, it is too early to determine the effectiveness of specific state legislation to prevent business activities which adversely impact on human rights. However, there remains a real risk that the legislation introduced may not be effective as a means of prevention.

3.3 HRDD Effectiveness and Rights Holders

A 2017 report by the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights, emphasised the need to ensure that rights holders are an integral part of any process that aims to provide an effective remedy for corporate human rights abuses.Footnote 98 HRDD has both preventative and remedial elements to it and ensuring the participation of rights holders in the process is a key aspect. As noted by the report, ‘[h]uman rights are best advanced when the “experiences, perspectives, interests, and opinions [of the rights holders] deeply inform how remedy mechanisms are created and implemented”’.Footnote 99 Studies demonstrate that rights holders—including workers and representative organisations—are crucial to a HRDD process. One study notes that a significant impediment to improving workplace conditions is the lack of a ‘comprehensive and accountable means of engaging workers as well as their unions’.Footnote 100

In assessing the effectiveness of HRDD, an important aspect is whether it institutionalises new mechanisms by which rights holders (who are likely to be workers, local communities and others) may meaningfully challenge corporate practices. The access to an effective remedy for rights holders is, after all, the third pillar of the UNGPs. If HRDD is defined by policies and practices that prioritize process over outcomes, then it will be a less effective mechanism for preventing corporate human right impacts and instead be a ‘legitimization exercise for corporate operations’.Footnote 101 The challenge here is to ensure that HRDD is designed and implemented in a manner that is sufficiently flexible to cater for its application in a variety of sectors but not so flexible that it is overly deferential to business practices and discounts the participation of rights holders. As Ingrid Landau notes, ‘the absence of rights for those external to the business to participate in corporate HRDD processes is problematic’Footnote 102 and while the UNGPs encourage such participation, mandatory HRDD that requires rights holders be part of that process is more likely to ensure HRDD is effective. If HRDD is articulated and understood by business as solely a risk management process, then this may reduce rather than open up the opportunity for rights holders to be heard. As we have noted, HRDD as understood in the UNGPs differs from conventional corporate due diligence because its focus is not risk to the business but risks to people affected by the business’s activitiesFootnote 103 which, should open up the space for the participation of rights holders.

As an example, the French Duty of Vigilance Act 2017, does provide for opportunities for the participation of rights holders in HRDD but its effectiveness is still being tested.Footnote 104 The broad purpose of the French law is to require relevant businesses to identify risks and prevent serious violations of human rights to protect better the health and safety of both people and the environment. The law sets out the broad parameters of what an adequate HRDD equivalent should look like and includes compliance mechanisms that incorporate potential regulatory roles for both public and private actors. The Duty of Vigilance Act requires consultation with worker representatives when business is developing a process to identify risks and undertake consultation with stakeholders in implementing their vigilance plans. This approach which prioritises HRDD, but arguably lacks clarity around that consultation process,Footnote 105 stands in contrast to the reporting focus of laws such as those emanating from the UK and Australia to deal with modern slavery, which implicitly encourage, but do not explicitly require, consultation with rights holders.

Beyond legislation, there are lessons from other areas that can and should inform the development of HRDD as it seeks to ensure rights holders are an integral part of the process. For example, emerging worker-driven social responsibility initiatives (‘WSR’) are an innovative practice that involve workers in the creation, monitoring and enforcement of human rights standards. The adoption of WSR can provide for a more effective HRDD process that ensures rights holders are central to the process of not only identifying business and human rights issues but also in designing mechanisms for their redress. Examples include two US-based programs (Fair Food Program and Milk with Dignity) and a more recent Australian initiative (the Cleaning Accountability Framework, CAF).Footnote 106 In each of these examples, the initiatives explicitly engage workers—as the best placed workplace monitors—to ensure that processes to prevent and redress human rights harms are not only worker-centred but also worker driven.Footnote 107 The OECD, which has led the development of practical guidance for business and states on HRDD, notes that enterprises should involve ‘workers and trade unions and representative organisations of the workers’ own choosing’ in HRDD.Footnote 108

Further guidance on HRDD and the necessity of incorporating input from rights holders, may also be gained from the development, over many decades, of the indigenous right to consultation and the concept of free, prior and informed consent (‘FPIC’) as ‘implemented’ in the business and human rights field. Consultation with indigenous populations is an international obligation of states under ILO Convention 169. However, FPIC suffers for lack of clarity and a consensus over whom must be consulted with and what form that should take.Footnote 109 As such, the right to consultation has been the focus of demands, advocacy, and litigation by indigenous communities around the globe, often contesting impacts of the extractive sector on their lands and communities.Footnote 110 FPIC, while not grounded in an international treaty, is (along with consultation) increasingly regarded as something to be incorporated into corporate human rights policies and both concepts essentially serve as gatekeeper ‘rights’ to protect the sanctity and observance of other rights and norms with which they interrelate.Footnote 111 While FPIC has been extensively explored in academic literature with a focus on the four terms that define it—free, prior, informed, consent—one overarching key aspect of FPIC relevant to this discussion, is its bottom-up nature, which preserves rights holders as key decision makers. For example, if Rio Tinto had undertaken FPIC with the relevant indigenous communities in Australia as part of an effective HRDD process, then its destruction of Juukan Gorge would not have occurred.Footnote 112 Rights holders in both FPIC and HRDD should be seen as essential participatory stakeholders who can provide the best form of protection to prevent and mitigate corporate harms.Footnote 113

Accepting that HRDD would be improved by the involvement of rights holders in both the design and implementation of the process is one thing, making it happen is quite another. Emerging legislative and non-legislative examples in the business and human rights field demonstrate a growing acceptance, even expectation in some sectors, that rights holders should be integral to the process. However, moving beyond a form of HRDD that incorporates stakeholder participation as symbolic to one that is substantive, will require the state not only to mandate such consultation as an explicit requirement of HRDD, but also to provide greater clarity around the scope of such consultation and participation.

4 HRDD—Looking Forward

Just one year after the adoption of the UNGPs in 2011, Peter Muchlinski warned that HRDD, if interpreted as an obligation-of-process (compared to one of outcome) carried the risk that it might ‘degenerate into a “tick-box” exercise designed for public relations purposes’Footnote 114 rather than a serious integral part of corporate decision-making. HRDD is now at the crossroads as it begins to become part of legislation, which will firmly test its potential to contribute substantively to the prevention of corporate human rights abuses.

At the same time, the COVID-19 pandemic has raised many issues in relation to how businesses have acted with regard to the human rights impacts on supply chains. As noted by the International Trade Union Confederation, the pandemic has ‘exposed the fragility of global supply chains and the enormous risks to human and labour rights in a highly interconnected global economy that is not governed by the rule of law’.Footnote 115 The economic impact of the pandemic has severely affected workers around the world with these impacts falling disproportionately on vulnerable communities, including migrant workers, supply chain workers and female workers.Footnote 116 A survey conducted by the CHRB in 2020 concluded that ‘most companies failed to demonstrate that their response to the pandemic was adequate to limit negative impacts on stakeholders, especially in their supply chains, and to ensure that their rights were respected’, though it did note that ‘[o]verall, companies with robust human rights due diligence processes in place demonstrated that they were better equipped to respond to the crisis’.Footnote 117 In the aftermath of the pandemic, there is an opportunity for changeFootnote 118 so that HRDD, if designed and implemented effectively, can potentially play a role in preventing and mitigating corporate human rights impacts.

The emergence and development of HRDD in business and human rights in the last ten years has led to some subtle and not so subtle shifts in approaches from government, business, civil society, trade unions and workers in how they identify and communicate risk and impact around human rights. There remains incoherence between legislative approaches, business practices and the demands of workers and their representatives, however, HRDD retains potential to reshape preventative approaches to mitigating adverse human rights harms.

In further developing HRDD as a preventative tool in business and human rights, consideration should be given to ensuring HRDD is mandated by the state in a manner that provides clarity around its scope and includes an appropriate enforcement framework to engender compliance. Studies demonstrate that laws focused simply on disclosure or reporting of risks have had limited success in improving business practices or providing accountability for impacted rights holders.Footnote 119 Shining a light on abusive labour practices is a useful but insufficient step in addressing the problem. HRDD must be a holistic and ongoing process that extends well beyond workplace audits. The development of legal frameworks that provide clarity to the obligations inherent in HRDD are key to increasing its effectiveness. However, simply institutionalising HRDD will not automatically prevent adverse impacts on human rights. HRDD when implemented must focus on outcomes not just process, and it is essential that business accepts HRDD as a mechanism that demands a change in decision-making approaches and substantive compliance with human rights standards, rather than merely symbolic compliance. The laws mandating HRDD should both incentivise business to implement HRDD effectively and provide for accountability if they do not. To have a chance of being effective, HRDD must also include rights holders as principal participants in the process. As the UNGPs propose, the HRDD framework should focus on the risks to rights holders rather than the risks to the business itself. The involvement of rights holders themselves in the process is key to ensuring both the effective identification and potential remediation of such risks.

While the concept of HRDD has increased in prominence in the last decade, there remains significant ambiguity around its preventative value and the years ahead will determine its transformative potential to prevent and redress corporate human rights harms. The regulation of corporate activity with respect to human rights requires a multiplicity of stakeholders actively participating in a nuanced mix of public and private regulatory efforts. Emerging HRDD legislative initiatives do have the potential to change the nature and possibility of developing a firmer basis for corporate accountability for human rights, but states must be able and willing to act on their duty to protect human rights. This will probably be done most effectively by states working with a variety of non-state actors and rights holders to develop the requisite HRDD framework.

Notes

Human Rights Council, ‘Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights: Implementing the United Nations “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework: Report of the Special Representative of the Secretary-General on the issue of Human Rights and Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises’, UN Doc. A/HRC/17/31, 21 March 2011 (‘UNGPs’), Guiding Principle 13.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) et al. (2017), p. 5.

The relevant international standards are discussed in the next section.

See Human Rights Council, ‘Protect, Respect and Remedy: A Framework for Business and Human Rights’, Report to the UN Human Rights Council (‘Framework Report’), UN Doc. A/HRC/8/5, 7 April 2008, www.reports-and-materials.org/Ruggie-report-7-Apr-2008.pdf, para. 46: ‘The social license to operate is based in prevailing social norms that can be as important to a business’ success as legal norms’.

International Bar Association, IBA Practical Guide on Business and Human Rights for Business Lawyers, 28 May 2016, https://www.ibanet.org/MediaHandler?id=d6306c84-e2f8-4c82-a86f-93940d6736c4, p. 13.

See, for example, Milieudefensie v Royal Dutch Shell, District Court of the Hague, 26 May 2021, ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2021:5339, available at https://uitspraken.rechtspraak.nl/inziendocument?id=ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2021:5339, especially para. 4.4.11.

See McCorquodale and Simons (2007). For example, in Social and Economic Rights Action Centre v Nigeria, where the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights held that ‘[the state of Nigeria is in violation] of local people’s rights to […] health […] and life [by] breaching its duty to protect the Ogoni people from damaging acts of oil companies’. Social and Economic Rights Action Centre v Nigeria (2001) AHRLR 60 (ACHPR 2001), para. 59.

Milieudefensie v Royal Dutch Shell, supra n. 6, para. 4.4.13.

Ibid., para. 56.

Human Rights Council, Business and Human Rights: ‘Towards Operationalizing the “Protect, Respect and Remedy” Framework’, A/HRC/11/13, 22 April 2009, para. 71. See also the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights, ‘The report of the Working Group on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises’, UN Doc. A/73/163, 16 July 2018, para. 10, and OECD, OECD-Due-Diligence Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct (2018), para. 16 (‘OECD RBC Guidance’).

OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises 1976, amended in 2011, https://www.oecd.org/investment/mne/48004323.pdf (‘OECD Guidelines’). See also the OECD RBC Guidance, supra n. 10.

ILO Tripartite Declaration of Principles concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy 2017, https://www.ilo.org/empent/areas/mne-declaration/WCMS_570332/lang--en/index.htm. It applies to states, trade unions and businesses.

International Finance Organisation (IFC) Environmental and Social Performance Standards 2012, https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/Topics_Ext_Content/IFC_External_Corporate_Site/Sustainability-At-IFC/Policies-Standards/Performance-Standards. The IFC is part of the World Bank.

The Equator Principles 2013, https://equator-principles.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/03/equator_principles_III.pdf. The Equator Principles are used in project finance, https://equator-principles.com/about/.

UN Working Group on the Issue of Human Rights and Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises, ‘Corporate human rights due diligence—emerging practices, challenges and ways forward’, UN Doc. A/73/163, 16 July 2018, para. 10.

Ibid.

For a full discussion on the definition of HRDD, see Bonnitcha and McCorquodale (2017).

Rühmkorf and Walker (2018).

OHCHR, ‘The Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights: An Interpretive Guide’, UN Doc. HR/PUB/12/02 (2012), https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Publications/HR.PUB.12.2_En.pdf, p. 4.

See, for example, Fasterling (2017).

See UNGPs, supra n. 1, p. 13.

See, for example, OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chain of Minerals from Conflict-Affected Areas (2016), https://www.oecd.org/daf/inv/mne/OECD-Due-Diligence-Guidance-Minerals-Edition3.pdf; OECD Responsible Business Conduct for Institutional Investors: Key Considerations for due diligence under the OECD Guidelines for MNEs (2016), https://mneguidelines.oecd.org/RBC-for-Institutional-Investors.pdf.

UNGPs, supra n. 1, Commentary to Guiding Principle 12.

OECD Guidelines, supra n. 11, Section VI Environment.

See McCorquodale (2020).

For example, a joint statement from nine UN Special Procedures mandate-holders in September 2019 made clear that ‘[a]mong the human rights being threatened and violated by climate change are the rights to life, health, food, water and sanitation, a healthy environment, an adequate standard of living, housing, property, self-determination, development and culture’. OHCHR, United Nations Climate Action Summit, New York, 23 September 2019. Also see, Macchi (2020). It is also consistent with the OECD Guidelines, supra n. 11, Section VI Environment, para. 6, which notes that businesses should encourage, in their supply chain, ‘[the] development and provision of products or services that have no undue environmental impacts; are safe in their intended use; reduce greenhouse gas emissions; are efficient in their consumption of energy and natural resources; can be reused, recycled, or disposed of safely’. And for recent case law, Milieudefensie v Royal Dutch Shell, supra n. 6, para. 4.4.11.

See Chimisso Dos Santos and Seck (2020), p. 168.

UN Human Rights Council, ‘Elaboration of an International Legally Binding Instrument on Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises with Respect to Human Rights’, UN Doc. A/HRC Res. 26/9, 26 June 2014.

OEIGWG, ‘Legally Binding Instrument to Regulate, in International Human Rights Law, the Activities of Transnational Corporations and Other Business Enterprises’, 16 July 2019, (‘Revised Draft’), https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/HRBodies/HRCouncil/WGTransCorp/OEIGWG_RevisedDraft_LBI.pdf.

Ibid., emphasis added.

See Chambers and Yilmaz Vastardis (2021).

The California Transparency in Supply Chains Act 2010 was passed before the UNGPs.

For further discussion on the Australian legislation, see Landau and Marshall (2018).

Regulations passed after 2011 which are relevant to business and human rights includes the Peru Labour Code 2014 (on child labour) and the Indian National Guidelines on Responsible Business Conduct 2018.

EU Regulation No. 995/2010 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 October 2010 laying down the obligations of operators who place timber and timber products on the market, OJ 2010, L 295/23.

The EU Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council setting up a Union system for supply chain due diligence self-certification of responsible importers of tin, tantalum and tungsten, their ores, and gold originating in conflict-affected and high-risk areas, COM/2014/0111 final—2014/0059 (COD).

See, for example, the European Coalition for Corporate Justice, EU Model Legislation on Corporate Responsibility to Respect Human Rights and the Environment (February 2020), http://corporatejustice.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/2020-legal-brief.pdf.

EU Parliament Working Group on Responsible Business Conduct, Speech by Commissioner Reynders in RBC webinar on due diligence, 30 April 2020, https://responsiblebusinessconduct.eu/wp/2020/04/30/speech-by-commissioner-reynders-in-rbc-webinar-on-due-diligence/.

European Parliament resolution of 10 March 2021 with recommendations to the Commission on corporate due diligence and corporate accountability, 2020/2129(INL), Texts adopted—Corporate due diligence and corporate accountability—Wednesday, 10 March 2021 (europa.eu).

Vedanta Resources v Lungowe [2019] UKSC 20, and Okpabi v Shell [2021] UKSC 3.

Four Nigerian Farmers and Milieudefensie v Royal Dutch Shell, Court of Appeal of The Hague, 29 January 2021, ECLI:NL:GHDHA:2021:132, ECLI:NL:GHDHA:2021:133, ECLI:NL:GHDHA:2021:134.

Sanda v PTTEP Australasia (Ashmore Cartier) Pty Ltd (No. 7) [2021] FCA 237, Federal Court of Australia.

Begum v Maran [2021] EWCA Civ. 326 in the UK.

Nevsun Resources Ltd. v Araya, 2020 SCC 5.

Ibid., para. 128. There are, though, limits on the extent to which domestic courts will protect claimants seeking remedies for harms caused by business in other jurisdictions. This can be because of domestic law jurisdictional restrictions (e.g., Kiobel v Royal Dutch Shell 569 US 108 (2013) in the US) and private international law rules, such as the foreign state’s statute of limitations (e.g., Jabir and others v KiK, Regional Court of Dortmund, 10 January 2019, Case No. 7 O 95/15 in Germany).

Milieudefensie v Royal Dutch Shell, supra n. 6.

Ibid., para. 4.4.11 The court concluded that Shell did have an obligation to reduce the CO2 emissions of the whole Shell corporate group’s activities by net 45% by the end of 2030 relative to that existing in 2019, para. 4.4.49.

Hsin et al. (2021).

Ibid., p. 21.

See Ruggie, Rees and Davis (2021), p. 181.

Smit et al. (2020a), p. 142. Only 9.7 percent of business respondents disagreed with this proposition. Note that one of the authors of this contribution was a co-author for this Study.

Ibid., see also the Report by the UN Working Group on Business and Human Rights, ‘Connecting the Business and Human Rights and the Anti-Corruption Agendas’, UN Doc. A/HRC/44/43, 17 June 2020, p. 14, https://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Issues/Business/A_HRC_44_43_AdvanceEditedVersion.pdf.

See, for example, Smit et al. (2020b).

See European Coalition for Corporate Justice (ECCJ) (2021).

Smit et al. (2020a), pp. 48–50.

World Benchmarking Alliance (2021).

Corporate Human Rights Benchmark (CHRB) and World Benchmarking Alliance (2020).

Ibid., Key Finding 5.

Ibid., Key Finding 4.

Human Rights Council, ‘Taking stock of investor implementation of the Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights’, Report of the UN Working Group on the issue of human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises, UN Doc. A/HRC/47/39/Add.1, 17 June 2021, https://undocs.org/A/HRC/47/39/Add.1.

Ibid., para. 14.

Aizawa, Bradlow and Wachenfeld (2018), p. 2.

Ibid., pp. 2–3.

O’Connor and Labowitz (2017).

Narine (2015).

Ford and Nolan (2020).

Walk Free, WikiRate and Business, and Human Rights Resource Centre (2020), p. 9.

German Federal Foreign Office, National Action Plan for Business and Human Rights (2016).

See summary in Virtual conference of the Federal Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs: ‘Global Supply Chains—Global Responsibility’—EU2020—EN, Workshop #1, 7 October 2020.

See McCorquodale et al. (2017), p. 209.

Terwindt and Armstrong (2019), p. 248.

Nolan and Frishling (2020), p. 118.

Ford and Nolan (2020).

Nolan and Frishling (2020), p. 119.

LeBaron, Lister and Dauvergne (2017).

Business & Human Rights Resource Centre (2021a).

See Unilever (2021).

See, for example, Danish Institute for Human Rights and Nestlé (2013).

See, for example, the role of the International Council on Mining and Metals (2012).

Ford and Nolan (2020), p. 33, references omitted.

See Skinner et al. (2013).

Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014, amending Directive 2013/34/EU as regards disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups, OJ 2014, L 330/1. See Bold (2017).

Gilad (2010), p. 487.

Ibid., p. 489.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2017), p. 9.

Harris and Nolan (2021), pp. 604, 606.

Hess and Ford (2008).

Quijano and Lopez (2021), p. 254.

UN General Assembly, ‘Report of the Working Group on the issue of Human rights and transnational corporations and other business enterprises’, UN Doc. A/72/162, 18 July 2017.

Ibid., para. 20.

Locke (2013).

Landau (2019), p. 243.

UNGPs, supra n. 1, Guiding Principle 17(a), and Commentary.

Cossart et al. (2017).

Ford and Nolan (2020), p. 36.

Outhwaite and Martin-Ortega (2019).

OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains in the Garment and Footwear Sector (2017), https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/governance/oecd-due-diligence-guidance-for-responsible-supply-chains-in-the-garment-and-footwear-sector_9789264290587-en, p. 29.

International Labour Organization, Convention 169—Indigenous and Tribal Peoples, opened for signature 27 June 1989 (entered into force 5 September 1991).

Kemp and Owen (2017).

Nagar (2021).

RESOLVE (2015), p. 32.

Muchlinski (2012), p. 158.

International Trade Union Confederation (2020b), p. 5.

International Law Organisation (2021).

Corporate Human Rights Benchmark and World Benchmarking Alliance (2021), p. 4.

International Trade Union Confederation (2020a).

Focus on Labour Exploitation (FLEX) (2018).

References

Abbott KW, Snidal D (2002) Values and interests: international legalisation in the fight against corruption. J Leg Stud 31(S1):S141–S177

Aizawa M, Bradlow D, Wachenfeld M (2018) International financial regulatory standards and human rights: connecting the dots. Manchester J Int Econ Law 15(1):2–44

Baccaro L, Mele V (2011) For lack of anything better? International organisations and global corporate codes. Public Adm 89(2):451–470

Bold F (2017) Comparing the implementation of the EU Non-Financial Reporting Directive in the UK, Germany, France and Italy. http://www.purposeofcorporation.org/comparing-the-eu-non-financial-reporting-directive.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct 2021

Bonnitcha J, McCorquodale R (2017) The concept of ‘due diligence’ in the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. Eur J Int Law 28(3):899–919

Business & Human Rights Resource Centre (2021a) Social audit liability. Hard law strategies to redress weak social assurances. https://media.business-humanrights.org/media/documents/2021_CLA_Annual_Briefing_v5.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct 2021

Business & Human Rights Resource Centre (2021b) Companies & investors in support of mHRDD. https://www.business-humanrights.org/en/big-issues/mandatory-due-diligence/companies-investors-in-support-of-mhrdd/. Accessed 20 Oct 2021

Chambers R, Yilmaz Vastardis A (2021) Human rights disclosure and due diligence laws: the role of regulatory oversight in ensuring corporate accountability. Chic J Int Law 21(2):323–366

Chimisso Dos Santos D, Seck SL (2020) Human rights due diligence and extractive industries. In: Deva S, Birchall D (eds) Research handbook on business and human rights. Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, pp 151–174

Corporate Human Rights Benchmark (CHRB), World Benchmarking Alliance (2020) Corporate Human Rights Benchmark Key Findings Report. https://www.worldbenchmarkingalliance.org/research/corporate-human-rights-benchmark-2020-key-findings-report/. Accessed 20 Oct 2021

Corporate Human Rights Benchmark (CHRB), World Benchmarking Alliance (2021) COVID-19 and human rights: assessing the private sector’s response to the pandemic across five sectors. https://assets.worldbenchmarkingalliance.org/app/uploads/2021/02/CHBR-Covid-Study_110221_FINAL.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct 2021

Cossart S, Chaplier J, Beau de Lomenie T (2017) The French Law on Duty of Care: a historic step towards making globalisation work for all. Bus Human Rights J 2(2):317–323

Couvreur P (2016) The International Court of Justice and the effectiveness of international law. Brill | Nijhoff, Leiden

Danish Institute for Human Rights and Nestle (2013) Taking the human rights walk: Nestle’s experience assessing human rights impacts in its business activities. http://www.nestle.com/asset-library/documents/library/documents/corporate_social_responsibility/nestle-hria-white-paper.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct 2021

De Felice D (2015) Business and human rights indicators to measure the corporate responsibility to respect: challenges and opportunities. Hum Rights Q 37(2):511–555

De Visscher C (1967) Les effectivités du droit international public. Pedone, Paris

Deva S (2012) Regulating corporate human rights violations. Routledge, London

Deva S (2021) ‘The UN Guiding Principles’ orbit and other regulatory regimes. Bus Human Rights J 6(2):336–351

European Coalition for Corporate Justice (ECCJ), Corporate Responsibility (CORE) Coalition (2020) Debating mandatory human rights due diligence legislation: a reality check. Brussels. http://corporatejustice.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/03/debating-mhrdd-legislation-a-reality-check.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct 2021

European Coalition for Corporate Justice (ECCJ) (2021) Off the hook? How business lobbies against liability for human rights and environmental abuses. https://corporatejustice.org/publications/off-the-hook-how-business-lobbies-against-liability-for-human-rights-and-environmental-abuses/. Accessed 20 Oct 2021

Fasterling B (2017) Human rights due diligence as risk management: social risk versus human rights risk. Bus Human Rights J 2(2):225–247

Focus on Labour Exploitation (FLEX) (2018) Seeing through transparency: making corporate accountability work for workers. https://www.labourexploitation.org/publications/seeing-through-transparency-making-corporate-accountability-work-workers. Accessed 20 Oct 2021

Ford J, Nolan J (2020) Regulating transparency on human rights and modern slavery in corporate supply chains: the discrepancy between human rights due diligence and the social audit. Aust J Human Rights 26(1):27–45

Formentini M, Tattichi P (2016) Corporate sustainability approaches and governance mechanisms in sustainable supply chain management. J Clean Prod 112(3):1920–1933

Gilad S (2010) It runs in the family: meta-regulation and its siblings. Regul Gov 4(4):485–506

Harris H, Nolan J (2021) Learning from experience: comparing legal approaches to foreign bribery and modern slavery. Cardozo Int Comp Law Rev 4(2):603–652

Hess D, Ford C (2008) Corporate corruption and reform undertakings: a new approach to an old problem. Cornell Int Law J 41(2):307–346

Hsin LKE, New S, Pietropaoli I, Smit L (2021) Effectiveness of Section 54 of the Modern Slavery Act. https://modernslaverypec.org/resources/tisc-effectiveness. Accessed 20 Oct 2021

International Council on Mining and Metals (2012) Integrating human rights due diligence into corporate risk management processes. https://www.icmm.com/website/publications/pdfs/social-performance/2012/guidance_human-rights-due-diligence.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct 2021

International Labour Organisation (2021) Slow jobs recovery and increased inequality risk long-term COVID-19 scarring. ILO Newsroom. https://www.ilo.org/global/about-the-ilo/newsroom/news/WCMS_794834/lang--en/index.htm. Accessed 20 Oct 2021

International Trade Union Confederation (2020a) Let’s build resilient economies with a new social contract. Take Action! http://petitions.ituc-csi.org/let-s-build-resilient-economies-with-a-new-social-contract. Accessed 20 Oct 2021

International Trade Union Confederation (2020b) Towards mandatory due diligence in global supply chains. https://www.ituc-csi.org/towards_mandatory_due_diligence. Accessed 20 Oct 2021

Kemp D, Owen JR (2017) Corporate readiness and the human rights risks of applying FPIC in the global mining industry. Bus Human Rights J 2(1):163–169

Laine A (2015) Integrated reporting: fostering human rights accountability for multinational corporations. George Wash Int Law Rev 47:639–667

Landau I (2019) Human rights due diligence and the risk of cosmetic compliance. Melbourne J Int Law 20(1):221–248

Landau I, Marshall S (2018) Should Australia be embracing the Modern Slavery Model of Regulation? Fed Law Rev 46(2):313–339

LeBaron G (2020) Combatting modern slavery why labour governance is failing and what we can do about it. Polity Press, UK

LeBaron G, Lister J, Dauvergne P (2017) Governing global supply chain sustainability through the ethical audit regime. Globalisations 14(6):958–975

Locke R (2013) The promise and limits of private power: promoting labor standards in a global economy. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

López MB (2005) Indigenous peoples and natural resources under the Inter-American system of human rights: between privatisation and the exercise of human rights. In: De Feyter K, Gómez Isa F (eds) Privatisation and human rights in the age of globalisation. Intersentia, Antwerp, pp 289–324

Louche C, Hebb T (2014) SRI in the 21st century: does it make a difference to society. Crit Stud Corp Responsib Govern Sustain 7:275–297

Lozano R et al (2016) Elucidating the relationship between sustainability reporting and organisational change management for sustainability. J Clean Prod 125:168–188

Macchi C (2020) The climate change dimension of business and human rights: the gradual consolidation of a concept of ‘climate due diligence’. Bus Human Rights J 6(1):93–119

McCorquodale R (2020) Comparative analysis of country reports. In: European Commission (ed) Study on due diligence requirements through the supply chain, 1st edn. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg, pp 199–213. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/8ba0a8fd-4c83-11ea-b8b7-01aa75ed71a1/%20language-en. Accessed 20 Oct 2021

McCorquodale R, Simons P (2007) Responsibility beyond borders: state responsibility for extraterritorial violations by corporations of international human rights law. Mod Law Rev 70(4):598–625

McCorquodale R, Smit L, Brooks R, Neely S (2017) Human rights due diligence in law and practice: good practices and challenges for business enterprises. Bus Human Rights J 2(2):195–224

Mehra A, Blackwell S (2016) The rise of non-financial disclosure: reporting on respect for human rights. In: Baumann-Pauly D, Nolan J (eds) Business and human rights: from principles to practice. Routledge, New York, pp 276–283

Muchlinski P (2012) Implementing the new UN Corporate Human Rights Framework: implications, corporate law. Bus Ethics 22(1):145–177

Muchlinski P (2021) The impact of the UN Guiding Principles on business attitudes to observing human rights. Bus Human Rights J 6(2):212–226

Nagar A (2021) The Juukan Gorge incident: key lessons on free, prior, and informed consent. Bus Human Rights J 6(2):377–383

Narine M (2015) Disclosing disclosure’s defects: addressing corporate responsibility for human rights impacts. Columbia Law Rev 47(1):84–150

Nichols P (1999) Regulating transnational bribery in times of globalisation and fragmentation. Yale J Int Law 24(1):257–303

Nolan J, Frishling N (2020) Human rights due diligence and the (over) reliance on social auditing in supply chains. In: Deva S, Birchall D (eds) Research handbook on human rights and business. Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham, pp 108–129

O’Connor C, Labowitz S (2017) Putting the ‘S’ in ESG: measuring human rights performance for investors. NYU Stern Center for Business and Human Rights, New York

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2017) The detection of foreign bribery. https://www.oecd.org/corruption/the-detection-of-foreign-bribery.htm. Accessed 20 Oct 2021

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) et al (2017) Promoting sustainable global supply chains: developing international standard, due diligence and grievance mechanisms. Paper presented at the 2nd Meeting of the G20 Employment Working Group, Hamburg, 15–17 Feb 2017

Outhwaite O, Martin-Ortega O (2019) Worker-driven monitoring—redefining supply chain monitoring to improve labour rights in global supply chains. Compet Chang 23(4):378–396

Parker C, Lehmann Nielsen V (2017) Compliance: 14 questions. In: Drahos P (ed) Regulatory theory: foundations and applications. ANU Press, Acton, pp 217–232

Quijano G, Lopez C (2021) Rise of mandatory human rights due diligence: a beacon of hope or a double-edged sword? Bus Human Rights J 6(2):241–254

RESOLVE (2015) From rights to results: an examination of agreements between international mining and petroleum companies and indigenous communities in Latin America. https://www.resolve.ngo/docs/from-rights-to-results-sept-2015-final-eng636885104660887798.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct 2021

Ruggie J, Rees C, Davis R (2021) Ten years after: from UN Guiding Principles to multi-fiduciary obligations. Bus Human Rights J 6(2):179–197

Rühmkorf A, Walker L (2018) Assessment of the concept of ‘duty of care’ in European legal systems for Amnesty International. European Institutions Office, London

Skinner G, McCorquodale R, De Schutter O, Lambe A (2013) The third pillar: access to judicial remedies for human rights violations by transnational business. European Coalition for Corporate Justice, Luxembourg

Smit L, Bright C, McCorquodale R et al (2020a) Study on due diligence requirements through the supply chain. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/8ba0a8fd-4c83-11ea-b8b7-01aa75ed71a1/%20language-en. Accessed 20 Oct 2021

Smit L, Bright C, Pietropaoli I, Hughes-Jennett J, Hood P (2020b) Business views on mandatory human rights due diligence regulation: a comparative analysis of two recent studies. Bus Human Rights J 5(2):261–269

Sobczak A (2006) Are codes of conduct in global supply chains really voluntary: from soft law regulation of labour relations to consumer law. Bus Ethics Q 16(2):167–184

Terwindt C, Armstrong A (2019) Oversight and accountability in the social auditing industry: the role of social compliance initiatives. Int Labour Rev 158(2):245–272

Triponel Consulting (2020) Another cross-border lawsuit using the new French duty of vigilance law. https://triponelconsulting.com/2020/10/12/cross-border-lawsuit-using-the-new-french-duty-of-vigilance-law/. Accessed 20 Oct 2021

UN Development Programme, United Nations Environment (2018) Managing mining for sustainable development: a sourcebook. https://www.undp.org/sites/g/files/zskgke326/files/publications/UNDP-MMFSD-HighResolution.pdf. Accessed 20 Oct 2021