Abstract

Objective

Hormones are often conceptualized as biological markers of individual differences and have been associated with a variety of behavioral indicators and characteristics, such as mating behavior or acquiring and maintaining dominance. However, before researchers create strong theoretical models for how hormones modulate individual and social behavior, information on how hormones are associated with dominant models of personality is needed. Although there have been some studies attempting to quantify the associations between personality traits, testosterone, and cortisol, there are many inconsistencies across these studies.

Methods

In this registered report, we examined associations between testosterone, cortisol, and Big Five personality traits. We aggregated 25 separate samples to yield a single sample of 3964 (50.3% women; 27.7% of women were on hormonal contraceptives). Participants completed measures of personality and provided saliva samples for testosterone and cortisol assays.

Results

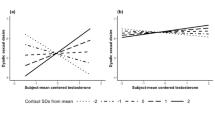

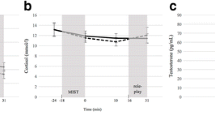

The results from multi-level models and meta-analyses revealed mostly weak, non-significant associations between testosterone or cortisol and personality traits. The few significant effects were still very small in magnitude (e.g., testosterone and conscientiousness: r = −0.05). A series of moderation tests revealed that hormone-personality associations were mostly similar in men and women, those using hormonal contraceptives or not, and regardless of the interaction between testosterone and cortisol (i.e., a variant of the dual-hormone hypothesis).

Conclusions

Altogether, we did not detect many robust associations between Big Five personality traits and testosterone or cortisol. The findings are discussed in the context of biological models of personality and the utility of examining heterogeneity in hormone-personality associations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We used the secondary data pre-registration template. A blinded copy of this document can be found on the OSF page for this project (https://osf.io/z8xfu/). We faithfully executed all of the specified analyses outlined in the Stage 1 manuscript with one exception—due to some missing data on study variables, the sample size fell just below 4000 participants. The pre-registration and Stage 1 manuscript predicted “at least 4000 participants” and our actual sample size was 3964 for testosterone (and 3518 for cortisol); we note the deviation here but view this as a minor problem given that we had approximately the same statistical power to estimate small effects.

There is some controversy over the correct effect size to quantify the magnitude of fixed effects in the content of multi-level modeling (Lorah 2018). We chose partial correlation coefficients derived from the estimates in the multi-level model. We did so because of their intuitive nature and the ease with which they could be subjected to a meta-analysis. However, there is also the perspective that computing correlation coefficients in this manner does not adequately account for the Level-2 unit measurement (in this case, study membership). Partial standardization also relies on sample characteristics (e.g., the standard deviation of each variable), which might also vary across samples. Rather, it is recommended to use an index like f2 because it is measure of variance explained that has clearer benchmarks of interpretation (Aiken et al. 1991; Cohen 1992). By using an effect size conversion based on the critical estimate from the models, the pseudo-partial-r’s presented in the tables account for the Level-2 membership. However, upon estimating the f2 measure for the substantive effects of interest, we also found that the effect sizes present were very small (f2 ≤ .003), consistent with the inferences made using correlation coefficients as effect sizes. For a full report of the magnitude of the effects across different effect size indices, please contact the second author for more details.

The use of alpha reliabilities is far from the ideal solution to correct for measurement unreliability in personality-hormone associations. Internal consistencies are not a good reflection of the reliability of short-form measures of personality. Correcting for unreliability using these indices likely leads to an overestimation of the association between personality traits and hormones. As a result, under this likely possibility, the corrected associations should be viewed with skepticism, particularly when they depart from the results found in other analyses. The results did not dramatically differ across analyses in the current project, but future research can more closely examine this question using different criteria than those that we pre-registered. For example, a better index for reliability might be test-retest correlations, which have been shown to be adequate when using these short-form scales (Gosling et al. 2003).

In our experience and a review of the literature, there is some ambiguity with respect to how we should have standardized the hormone values. Some studies did little or no standardizing beyond log-transformations, depending on the distribution of the hormone values. Other studies have standardized the hormone values within gender, given the different distributions between men and women (Zilioli et al. 2015). Yet others have standardized within a sample (across gender) to test questions related to mediation of gender differences (Schultheiss et al. 2020). One immediate implication is that the different standardization approaches affect the rank-ordering of men (who have higher and more variable testosterone values) and women, which has implications for the estimation of a gender difference and possibly estimations of personality-hormone associations. In a series of exploratory supplementary analyses, we examined how robust our findings were to different standardization procedures (e.g., standardizing hormones within a sample, standardizing hormones within men and women, within a sample). The findings were robust across all of these methods—the association between testosterone and cortisol was reproduced and all other effects were non-significant or did not surpass our pre-registered effect size cut-off.

References

Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., & Reno, R. R. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage.

Aluja, A., & García, L. F. (2007). Role of sex hormone-binding globulin in the relationship between sex hormones and antisocial and aggressive personality in inmates. Psychiatry Research, 152(2–3), 189–196.

Aluja, A., Garcia, O., & Garcia, L. F. (2002). A comparative study of Zuckerman's three structural models for personality through the NEO-PI-R, ZKPQ-III-R, EPQ-RS and Goldberg's 50-bipolar adjectives. Personality and Individual Differences, 33(5), 713–725.

Aluja, A., García, Ó., & García, L. F. (2003). Relationships among extraversion, openness to experience, and sensation seeking. Personality and Individual Differences, 35(3), 671–680.

Anderson, R. A., Bancroft, J., & Wu, F. C. (1992). The effects of exogenous testosterone on sexuality and mood of normal men. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 75(6), 1503–1507.

Apicella, C. L., Dreber, A., & Mollerstrom, J. (2014). Salivary testosterone change following monetary wins and losses predicts future financial risk-taking. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 39, 58–64.

Archer, J. (2006). Testosterone and human aggression: An evaluation of the challenge hypothesis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 30(3), 319–345.

Archer, J., Birring, S. S., & Wu, F. C. W. (1998). The association between testosterone and aggression among young men: Empirical findings and a meta-analysis. Aggressive Behavior, 24(6), 411–420.

Archer, J., Graham-Kevan, N., & Davies, M. (2005). Testosterone and aggression: A reanalysis of Book, Starzyk, and Quinsey's (2001) study. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 10(2), 241–261.

Arnold, A. P., & Breedlove, S. M. (1985). Organizational and activational effects of sex steroids on brain and behavior: A reanalysis. Hormones and Behavior, 19(4), 469–498.

Asendorpf, J. B., Penke, L., & Back, M. D. (2011). From dating to mating and relating: Predictors of initial and long-term outcomes of speed-dating in a community sample. European Journal of Personality, 25(1), 16–30.

Bird, B. M., Cid Jofré, V. S., Geniole, S. N., Welker, K. M., Zilioli, S., Maestripieri, D., Arnocky, S., & Carré, J. M. (2016). Does the facial width-to-height ratio map onto variability in men's testosterone concentrations? Evolution and Human Behavior, 37(5), 392–398.

Book, A. S., Starzyk, K. B., & Quinsey, V. L. (2001). The relationship between testosterone and aggression: A meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 6(6), 579–599.

Borkenau, P., & Ostendorf, F. (1993). NEO-Funf-Faktoren Inventar (NEO-FFI) nach Costa und McCrae. Göttingen: Hogrefe.

Brandes, C. M., Herzhoff, K., Smack, A. J., & Tackett, J. L. (2019). The p factor and the n factor: Associations between the general factors of psychopathology and neuroticism in children. Clinical Psychological Science, 7(6), 1266–1284.

Breedlove, S. M. (1994). Sexual differentiation of the human nervous system. Annual Review of Psychology, 45(1), 389–418.

Canli, T. (2006). Biology of personality and individual differences. New York: Guilford Press.

Canli, T. (2008). Toward a “molecular psychology” of personality. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 311–327). New York: The Guilford Press.

Casto, K. V., & Edwards, D. A. (2016). Testosterone, cortisol, and human competition. Hormones and Behavior, 82, 21–37.

Cattell, R. B. (1945). The principal trait clusters for describing personality. Psychological Bulletin, 42(3), 129–161.

Chopik, W. J. (2016). Age differences in conscientiousness facets in the second half of life: Divergent associations with changes in physical health. Personality and Individual Differences, 96, 202–211.

Cohen, J. (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112(1), 155–159.

Corker, K. S. (2020). Strengths and weaknesses of meta-analysis. In L. Jussim, S. Stevens, & J. Krosnick (Eds.), Research integrity in the behavioral sciences. New York: Oxford University Press https://psyarxiv.com/6gcnm/.

Costa Jr., P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1995). Domains and facets: Hierarchical personality assessment using the revised NEO personality inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 64(1), 21–50.

de Souza, F. T. A., Kummer, A., Silva, M. L. V., Amaral, T. M. P., Abdo, E. N., Abreu, M. H. N. G., Silva, T. A., & Teixeira, A. L. (2015). The Association of Openness Personality Trait with stress-related salivary biomarkers in burning mouth syndrome. Neuroimmunomodulation, 22(4), 250–255.

de Vries, R. E., Tybur, J. M., Pollet, T. V., & van Vugt, M. (2016). Evolution, situational affordances, and the HEXACO model of personality. Evolution and Human Behavior, 37(5), 407–421.

Deal, J. E., Halverson, C. F., Martin, R. P., Victor, J., & Baker, S. (2007). The inventory of Children's individual differences: Development and validation of a short version. Journal of Personality Assessment, 89(2), 162–166.

Dekkers, T. J., van Rentergem, J. A. A., Meijer, B., Popma, A., Wagemaker, E., & Huizenga, H. M. (2019). A meta-analytical evaluation of the dual-hormone hypothesis: Does cortisol moderate the relationship between testosterone and status, dominance, risk taking, aggression, and psychopathy? Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 96, 250–271.

Dickerson, S. S., & Kemeny, M. E. (2004). Acute stressors and cortisol responses: A theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychological Bulletin, 130, 355–391.

Doering, C. H., Brodie, H., Kraemer, H. C., Moos, R. H., Becker, H. B., & Hamburg, D. A. (1975). Negative affect and plasma testosterone: A longitudinal human study. Psychosomatic Medicine, 37(6), 484–491.

Edelstein, R. S., Stanton, S. J., Henderson, M. M., & Sanders, M. R. (2010a). Endogenous estradiol levels are associated with attachment avoidance and implicit intimacy motivation. Hormones and Behavior, 57, 230–236.

Edelstein, R. S., Yim, I. S., & Quas, J. A. (2010b). Narcissism predicts heightened cortisol reactivity to a psychosocial stressor in men. Journal of Research in Personality, 44, 565–572.

Edelstein, R. S., Chopik, W. J., & Kean, E. L. (2011). Sociosexuality moderates the association between testosterone and relationship status in men and women. Hormones and Behavior, 60(3), 248–255.

Edelstein, R. S., Kean, E. L., & Chopik, W. J. (2012). Women with an avoidant attachment style show attenuated estradiol responses to emotionally intimate stimuli. Hormones and Behavior, 61, 167–175.

Edwards, D. A., & Casto, K. V. (2013). Women's intercollegiate athletic competition: Cortisol, testosterone, and the dual-hormone hypothesis as it relates to status among teammates. Hormones and Behavior, 64(1), 153–160.

Fleischman, D. S., Navarrete, C. D., & Fessler, D. M. T. (2010). Oral contraceptives suppress ovarian hormone production. Psychological Science, 21(5), 750–752.

Francis, K. (1981). The relationship between high and low trait psychological stress, serum testosterone, and serum cortisol. Experientia, 37(12), 1296–1297.

Funder, D. C., & Ozer, D. J. (2019). Evaluating effect size in psychological research: Sense and nonsense. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 2(2), 156–168.

Giltay, E. J., Enter, D., Zitman, F. G., Penninx, B. W., van Pelt, J., Spinhoven, P., & Roelofs, K. (2012). Salivary testosterone: Associations with depression, anxiety disorders, and antidepressant use in a large cohort study. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 72(3), 205–213.

Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative "description of personality": The big-five factor structure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59(6), 1216–1229.

Goldey, K. L., & van Anders, S. M. (2011). Sexy thoughts: Effects of sexual cognitions on testosterone, cortisol, and arousal in women. Hormones and Behavior, 59(5), 754–764.

Gosling, S. D., Rentfrow, P. J., & Swann Jr., W. B. (2003). A very brief measure of the big-five personality domains. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(6), 504–528.

Grebe, N. M., Del Giudice, M., Emery Thompson, M., Nickels, N., Ponzi, D., Zilioli, S., Maestripieri, D., & Gangestad, S. W. (2019). Testosterone, cortisol, and status-striving personality features: A review and empirical evaluation of the dual hormone hypothesis. Hormones and Behavior, 109, 25–37.

Grotzinger, A. D., Mann, F. D., Patterson, M. W., Tackett, J. L., Tucker-Drob, E. M., & Harden, K. P. (2018). Hair and salivary testosterone, hair cortisol, and externalizing behaviors in adolescents. Psychological Science, 29(5), 688–699.

Hippocrates. (460 BC/1978). On the nature of man. In G. E. R. Lloyd (Ed.), Hippocratic writings (pp. 260–271). Pelican classics.

John, O. P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The big five trait taxonomy: History, measurement, and theoretical perspectives. In L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 102–138). New York: Guilford.

Josephs, R. A. (2009). Moving beyond dichotomies in research on oral contraceptives: A comment on Edwards and O'Neal. Hormones and Behavior, 56(2), 193–194.

Josephs, R. A., Sellers, J. G., Newman, M. L., & Mehta, P. H. (2006). The mismatch effect: When testosterone and status are at odds. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(6), 999–1013.

Jünger, J., Kordsmeyer, T. L., Gerlach, T. M., & Penke, L. (2018a). Fertile women evaluate male bodies as more attractive, regardless of masculinity. Evolution and Human Behavior, 39(4), 412–423.

Jünger, J., Motta-Mena, N. V., Cardenas, R., Bailey, D., Rosenfield, K. A., Schild, C., Penke, L., & Puts, D. A. (2018b). Do women's preferences for masculine voices shift across the ovulatory cycle? Hormones and Behavior, 106, 122–134.

Ketay, S., & Beck, L. A. (2017). Attachment predicts cortisol response and closeness in dyadic social interaction. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 80, 114–121.

Ketay, S., Welker, K. M., & Slatcher, R. B. (2017). The roles of testosterone and cortisol in friendship formation. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 76, 88–96.

Ketay, S., Welker, K. M., Beck, L. A., Thorson, K. R., & Slatcher, R. B. (2019). Social anxiety, cortisol, and early-stage friendship. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 36(7), 1954–1974.

Knight, E. L., Christian, C. B., Morales, P. J., Harbaugh, W. T., Mayr, U., & Mehta, P. H. (2017). Exogenous testosterone enhances cortisol and affective responses to social-evaluative stress in dominant men. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 85, 151–157.

Knight, E. L., Sarkar, A., Prasad, S., & Mehta, P. H. (2020). Beyond the challenge hypothesis: The emergence of the dual-hormone hypothesis and recommendations for future research. Hormones and Behavior, 123, 104657.

Knowles, S. R., Nelson, E. A., & Palombo, E. A. (2008). Investigating the role of perceived stress on bacterial flora activity and salivary cortisol secretion: A possible mechanism underlying susceptibility to illness. Biological Psychology, 77(2), 132–137.

Kordsmeyer, T. L., & Penke, L. (2019). Effects of male testosterone and its interaction with cortisol on self- and observer-rated personality states in a competitive mating context. Journal of Research in Personality, 78, 76–92.

Kordsmeyer, T. L., Hunt, J., Puts, D. A., Ostner, J., & Penke, L. (2018). The relative importance of intra- and intersexual selection on human male sexually dimorphic traits. Evolution and Human Behavior, 39(4), 424–436.

Kordsmeyer, T. L., Freund, D., Pita, S. R., Jünger, J., & Penke, L. (2019a). Further evidence that facial width-to-height ratio and global facial masculinity are not positively associated with testosterone levels. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, 5(2), 117–130.

Kordsmeyer, T. L., Freund, D., Vugt, M. v., & Penke, L. (2019b). Honest signals of status: facial and bodily dominance are related to success in physical but not nonphysical competition. Evolutionary Psychology, 17(3), 1474704919863164.

Kordsmeyer, T. L., Lohöfener, M., & Penke, L. (2019c). Male facial attractiveness, dominance, and health and the interaction between cortisol and testosterone. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, 5(1), 1–12.

Kordsmeyer, T. L., Stern, J., & Penke, L. (2019d). 3D anthropometric assessment and perception of male body morphology in relation to physical strength. American Journal of Human Biology, 31(5), e23276.

Krueger, R. F., & Johnson, W. (2008). Behavioral genetics and personality. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 287–310). New York: The Guildford Press.

Kurath, J., & Mata, R. (2018). Individual differences in risk taking and endogeneous levels of testosterone, estradiol, and cortisol: A systematic literature search and three independent meta-analyses. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 90, 428–446.

Liening, S. H., Stanton, S. J., Saini, E. K., & Schultheiss, O. C. (2010). Salivary testosterone, cortisol, and progesterone: Two-week stability, interhormone correlations, and effects of time of day, menstrual cycle, and oral contraceptive use on steroid hormone levels. Physiology & Behavior, 99, 8–16.

Lorah, J. (2018). Effect size measures for multilevel models: Definition, interpretation, and TIMSS example. Large-scale Assessments in Education, 6(1), 8.

Mazur, A., & Booth, A. (1998). Testosterone and dominance in men. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 21(3), 353–363.

McCabe, K. O., & Fleeson, W. (2012). What is extraversion for? Integrating trait and motivational perspectives and identifying the purpose of extraversion. Psychological Science, 23(12), 1498–1505.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (2008). The five-factor theory of personality. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 159–181). New York: Guilford.

Mehta, P. H., & Josephs, R. A. (2010). Testosterone and cortisol jointly regulate dominance: Evidence for a dual-hormone hypothesis. Hormones and Behavior, 58(5), 898–906.

Mehta, P. H., & Prasad, S. (2015). The dual-hormone hypothesis: A brief review and future research agenda. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 3, 163–168.

Mehta, P. H., Mor, S., Yap, A. J., & Prasad, S. (2015a). Dual-hormone changes are related to bargaining performance. Psychological Science, 26(6), 866–876.

Mehta, P. H., Welker, K. M., Zilioli, S., & Carré, J. M. (2015b). Testosterone and cortisol jointly modulate risk-taking. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 56, 88–99.

Mehta, P. H., Lawless DesJardins, N. M., van Vugt, M., & Josephs, R. A. (2017). Hormonal underpinnings of status conflict: Testosterone and cortisol are related to decisions and satisfaction in the hawk-dove game. Hormones and Behavior, 92, 141–154.

Meulenberg, P., Ross, H., Swinkels, L., & Benraad, T. (1987). The effect of oral contraceptives on plasma-free and salivary cortisol and cortisone. Clinica Chimica Acta, 165(2–3), 379–385.

Nater, U. M., Hoppmann, C., & Klumb, P. L. (2010). Neuroticism and conscientiousness are associated with cortisol diurnal profiles in adults—Role of positive and negative affect. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 35(10), 1573–1577.

Netter, P. (2004). Personality and hormones. In R. M. Stelmack (Ed.), On the psychobiology of personality: Essays in honor of Marvin Zuckerman (pp. 353–377). New York: Elsevier Inc..

Nettle, D. (2005). An evolutionary approach to the extraversion continuum. Evolution and Human Behavior, 26(4), 363–373.

Nettle, D. (2006). The evolution of personality variation in humans and other animals. American Psychologist, 61(6), 622–631.

Newman, M. L., Sellers, J. G., & Josephs, R. A. (2005). Testosterone, cognition, and social status. Hormones and Behavior, 47(2), 205–211.

Nickelsen, T., Lissner, W., & Schöffling, K. (1989). The dexamethasone suppression test and long-term contraceptive treatment: Measurement of ACTH or salivary cortisol does not improve the reliability of the test. Experimental and Clinical Endocrinology & Diabetes, 94(06), 275–280.

Peugh, J. L., & Enders, C. K. (2005). Using the SPSS mixed procedure to fit cross-sectional and longitudinal multilevel models. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 65(5), 717–741.

Portella, M. J., Harmer, C. J., Flint, J., Cowen, P., & Goodwin, G. M. (2005). Enhanced early morning salivary cortisol in neuroticism. American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(4), 807–809.

Prasad, S., Lassetter, B., Welker, K. M., & Mehta, P. H. (2019). Unstable correspondence between salivary testosterone measured with enzyme immunoassays and tandem mass spectrometry. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 109, 104373.

Reardon, K. W., Herzhoff, K., & Tackett, J. L. (2016). Adolescent personality as risk and resiliency in the testosterone–externalizing association. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 26(3), 390–402.

Reifman, A., & Keyton, K. (2010). Winsorize. In N. J. Salkind (Ed.), Encyclopedia of research design (pp. 1636–1638). Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Roberti, J. W. (2004). A review of behavioral and biological correlates of sensation seeking. Journal of Research in Personality, 38(3), 256–279.

Roberts, B. W., Chernyshenko, O. S., Stark, S., & Goldberg, L. R. (2005). The structure of conscientiousness: An empirical investigation based on seven major personality questionnaires. Personnel Psychology, 58(1), 103–139.

Rosenthal, R. (1979). The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin, 86(3), 638–641.

Roy, A. R. K., Cook, T., Carre, J. M., & Welker, K. M. (2019). Dual-hormone regulation of psychopathy: Evidence from mass spectrometry. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 99, 243–250.

Sarkar, A., Mehta, P. H., & Josephs, R. A. (2019). The dual-hormone approach to dominance and status-seeking. In O. C. Schultheiss & P. H. Mehta (Eds.), The international handbook of social neuroendocrinology. Abingdon: Routledge.

Schmidt, F. L., & Hunter, J. E. (1996). Measurement error in psychological research: Lessons from 26 research scenarios. Psychological Methods, 1(2), 199–223.

Schmitt, N. (1996). Uses and abuses of coefficient alpha. Psychological Assessment, 8(4), 350–353.

Schommer, N., Kudielka, B., Hellhammer, D., & Kirschbaum, C. (1999). No evidence for a close relationship between personality traits and circadian cortisol rhythm or a single cortisol stress response. Psychological Reports, 84(3), 840–842.

Schönbrodt, F. D., Hagemeyer, B., Brandstätter, V., Czikmantori, T., Gröpel, P., Hennecke, M., Israel, L. S. F., Janson, K. T., Kemper, N., Köllner, M. G., Kopp, P. M., Mojzisch, A., Müller-Hotop, R., Prüfer, J., Quirin, M., Scheidemann, B., Schiestel, L., Schulz-Hardt, S., Sust, L. N. N., Zygar-Hoffmann, C., & Schultheiss, O. C. (2020). Measuring implicit motives with the picture story exercise (PSE): Databases of expert-coded German stories, pictures, and updated picture norms. Journal of Personality Assessment, 1–14.

Schultheiss, O. C., & Mehta, P. H. (2019). Reproducibility in social neuroendocrinology: Past, present, and future. In O. C. Schultheiss & P. H. Mehta (Eds.), The International Handbook of Social Neuroendocrinology. Abingdon: Routledge.

Schultheiss, O. C., Wirth, M. M., Torges, C. M., Pang, J. S., Villacorta, M. A., & Welsh, K. M. (2005). Effects of implicit power motivation on Men's and Women's implicit learning and testosterone changes after social victory or defeat. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 88(1), 174–188.

Schultheiss, O. C., Köllner, M. G., Busch, H., & Hofer, J. (2020). Evidence for a robust, estradiol-associated sex difference in narrative-writing fluency. Neuropsychology.

Schwaba, T., Rhemtulla, M., Hopwood, C. J., & Bleidorn, W. (2020). A facet atlas: Visualizing networks that describe the blends, cores, and peripheries of personality structure. PLoS One, 15(7), e0236893.

Sellers, J. G., Mehl, M. R., & Josephs, R. A. (2007). Hormones and personality: Testosterone as a marker of individual differences. Journal of Research in Personality, 41(1), 126–138.

Simmons, J. P., Nelson, L. D., & Simonsohn, U. (2011). False-positive psychology: Undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychological Science, 22(11), 1359–1366.

Simons, D. J., Shoda, Y., & Lindsay, D. S. (2017). Constraints on generality (COG): A proposed addition to all empirical papers. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(6), 1123–1128.

Simonsohn, U., Nelson, L. D., & Simmons, J. P. (2014). P-curve and effect size: Correcting for publication Bias using only significant results. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9(6), 666–681.

Slatcher, R. B., Mehta, P. H., & Josephs, R. A. (2011). Testosterone and self-reported dominance interact to influence human mating behavior. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 2(5), 531–539.

Smeets-Janssen, M. M., Roelofs, K., Van Pelt, J., Spinhoven, P., Zitman, F. G., Penninx, B. W., & Giltay, E. J. (2015). Salivary testosterone is consistently and positively associated with extraversion: Results from the Netherlands study of depression and anxiety. Neuropsychobiology, 71(2), 76–84.

Soto, C. J., & John, O. P. (2017). The next big five inventory (BFI-2): Developing and assessing a hierarchical model with 15 facets to enhance bandwidth, fidelity, and predictive power. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 113(1), 117–143.

Stanton, S. J., Liening, S. H., & Schultheiss, O. C. (2011). Testosterone is positively associated with risk taking in the Iowa gambling task. Hormones and Behavior, 59(2), 252–256.

Stenstrom, E., & Saad, G. (2011). Testosterone, financial risk-taking, and pathological gambling. Journal of Neuroscience, Psychology, and Economics, 4(4), 254–266.

Stern, J., Gerlach, T. M., & Penke, L. (2020). Probing ovulatory-cycle shifts in women’s preferences for men’s behaviors. Psychological Science, 31(4), 424–436.

Tackett, J. L., Herzhoff, K., Harden, K. P., Page-Gould, E., & Josephs, R. A. (2014a). Personality × hormone interactions in adolescent externalizing psychopathology. Personality Disorders: Theory, Research, and Treatment, 5(3), 235–246.

Tackett, J. L., Kushner, S. C., Josephs, R. A., Harden, K. P., Page-Gould, E., & Tucker-Drob, E. M. (2014b). Hormones: Empirical contribution: Cortisol reactivity and recovery in the context of adolescent personality disorder. Journal of Personality Disorders, 28(1), 25–39.

Tackett, J. L., Reardon, K. W., Herzhoff, K., Page-Gould, E., Harden, K. P., & Josephs, R. A. (2015). Estradiol and cortisol interactions in youth externalizing psychopathology. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 55, 146–153.

Tackett, J. L., Herzhoff, K., Smack, A. J., Reardon, K. W., & Adam, E. K. (2017). Does socioeconomic status mediate racial differences in the cortisol response in middle childhood? Health Psychology, 36(7), 662–672.

Tops, M., & Boksem, M. A. (2011). Cortisol involvement in mechanisms of behavioral inhibition. Psychophysiology, 48(5), 723–732.

Tops, M., Boksem, M. A., Wester, A. E., Lorist, M. M., & Meijman, T. F. (2006). Task engagement and the relationships between the error-related negativity, agreeableness, behavioral shame proneness and cortisol. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 31(7), 847–858.

Treleaven, M. M. M., Jackowich, R. A., Roberts, L., Wassersug, R. J., & Johnson, T. (2013). Castration and personality: Correlation of androgen deprivation and estrogen supplementation with the big five factor personality traits of adult males. Journal of Research in Personality, 47(4), 376–379.

Turan, B., Tackett, J. L., Lechtreck, M. T., & Browning, W. R. (2015). Coordination of the cortisol and testosterone responses: A dual axis approach to understanding the response to social status threats. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 62, 59–68.

van Anders, S. M., Goldey, K. L., & Bell, S. N. (2014). Measurement of testosterone in human sexuality research: Methodological considerations. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 43(2), 231–250.

Van Elk, M., Matzke, D., Gronau, Q., Guang, M., Vandekerckhove, J., & Wagenmakers, E.-J. (2015). Meta-analyses are no substitute for registered replications: A skeptical perspective on religious priming. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 1365.

van Goozen, S. H. M., Matthys, W., Cohen-Kettenis, P. T., Thijssen, J. H. H., & van Engeland, H. (1998). Adrenal androgens and aggression in conduct disorder prepubertal boys and normal controls. Biological Psychiatry, 43(2), 156–158.

Vianello, M., Schnabel, K., Sriram, N., & Nosek, B. (2013). Gender differences in implicit and explicit personality traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(8), 994–999.

Vickers Jr, R., Hervig, L. H., Poth, M., & Hackney, A. C. (1995). Cortisol secretion under stress: Test of a stress reactivity model in young adult males (no. NHRC-95-17, Issue. https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a309366.pdf

von Borell, C. J., Kordsmeyer, T. L., Gerlach, T. M., & Penke, L. (2019). An integrative study of facultative personality calibration. Evolution and Human Behavior, 40(2), 235–248.

Wardecker, B. M., Chopik, W. J., LaBelle, O. P., & Edelstein, R. S. (2018). Is narcissism associated with baseline cortisol in men and women? Journal of Research in Personality, 72, 44–49.

Weinstein, T. A., Capitanio, J. P., & Gosling, S. D. (2008). Personality in animals. In O. P. John, R. W. Robins, & L. A. Pervin (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (Vol. 3, pp. 328–348). New York: The Guilford Press.

Welker, K. M., Lozoya, E., Campbell, J. A., Neumann, C. S., & Carré, J. M. (2014). Testosterone, cortisol, and psychopathic traits in men and women. Physiology & Behavior, 129, 230–236.

Welker, K. M., Goetz, S. M. M., & Carré, J. M. (2015). Perceived and experimentally manipulated status moderates the relationship between facial structure and risk taking. Evolution and Human Behavior, 36(6), 423–429.

Welker, K. M., Lassetter, B., Brandes, C. M., Prasad, S., Koop, D. R., & Mehta, P. H. (2016). A comparison of salivary testosterone measurement using immunoassays and tandem mass spectrometry. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 71, 180–188.

Welker, K. M., Roy, A. R. K., Geniole, S., Kitayama, S., & Carre, J. M. (2019). Taking risks for personal gain: An investigation of self-construal and testosterone responses to competition. Social Neuroscience, 14(1), 99–113.

Wingfield, J. C., Hegner, R. E., Dufty Jr., A. M., & Ball, G. F. (1990). The" challenge hypothesis": Theoretical implications for patterns of testosterone secretion, mating systems, and breeding strategies. The American Naturalist, 136(6), 829–846.

Wingfield, J. C., Jacobs, J., Tramontin, A., Perfito, N., Meddle, S., Maney, D., & Soma, K. (2000). Toward an ecological basis of hormone–behavior interactions in reproduction of birds. In K. Wallen & J. Schneider (Eds.), Reproduction in context (pp. 85–128). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Witbracht, M. G., Laugero, K. D., Van Loan, M. D., Adams, S. H., & Keim, N. L. (2012). Performance on the Iowa gambling task is related to magnitude of weight loss and salivary cortisol in a diet-induced weight loss intervention in overweight women. Physiology & Behavior, 106(2), 291–297.

Wu, Y., Shen, B., Liao, J., Li, Y., Zilioli, S., & Li, H. (2020). Single dose testosterone administration increases impulsivity in the intertemporal choice task among healthy males. Hormones and Behavior, 118, 104634.

Zilioli, S., & Bird, B. M. (2017). Functional significance of men’s testosterone reactivity to social stimuli. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology, 47, 1–18.

Zilioli, S., Ponzi, D., Henry, A., & Maestripieri, D. (2015). Testosterone, cortisol and empathy: Evidence for the dual-hormone hypothesis. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology, 1(4), 421–433.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Zachary W. Sundin and William J. Chopik share joint first authorship.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sundin, Z.W., Chopik, W.J., Welker, K.M. et al. Estimating the Associations between Big Five Personality Traits, Testosterone, and Cortisol. Adaptive Human Behavior and Physiology 7, 307–340 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40750-020-00159-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40750-020-00159-9