Abstract

Purpose

The necessary treatment duration of omalizumab in patients with severe asthma remains unclear. Currently, common practice is life-long therapy without adjustment of dose or treatment intervals. This study evaluated asthma control after either dosage interval extension or dose reduction in patients with asthma controlled by omalizumab.

Methods

Thirty-seven patients were assigned to receive either extended treatment interval (n = 26) or a reduction in omalizumab dosage (n = 11). The primary outcome was time until loss of asthma control.

Results

Nineteen patients (73%) of the extended interval group maintained good asthma control for at least 7–39 months. Of the remaining 7 patients, the median time to loss of asthma control was 8 months (range 5–35 months). In contrast, all patients in the dose reduction group lost asthma control. The median time of loss of control was 2 months (1–44 months). Extension of dose interval led to a significantly (P < 0.001) longer period of good asthma control than dose reduction.

Conclusion

If patients or physicians wish to reduce the cumulative dose of omalizumab after achieving good asthma control, extension of the interval between doses appears to be a better approach than dose reduction.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In 2015, 358 million people suffered from asthma worldwide making it the most common chronic respiratory disease with some 3.6%, or around 13 million, meeting the criteria having severe refractory asthma [1, 2]. Of these patients with severe refractory asthma, around 5 million live in countries with a high or high-to-middle sociodemographic index [2]. It is this patient group that is the main target of additional therapy with biologics as recommended by Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA) guidelines [3].

Perhaps the most widely used biologic is omalizumab, a humanized anti-immunoglobulin E (IgE) monoclonal antibody which interrupts the allergic cascade central to the pathophysiology of allergic asthma by sequestering free IgE and reducing its ability to induce allergen-induced mast cell and basophil degranulation [4]. The appropriate dose of omalizumab for adults is determined by baseline IgE (IU/ml), measured before the start of treatment, body weight (kg) and is administered subcutaneously every 2–4 weeks.

Used in this way, omalizumab has been shown repeatedly to be effective in severe allergic asthma [5,6,7]. Also, omalizumab has been shown to be cost-effective due a reduction of health-care resource use and improvement of work productivity through better disease control [8]. It is clear that prolonged omalizumab therapy leads to a chronic decrease in serum IgE [9] and continued benefit, as evidenced by improved asthma symptom control and reduced exacerbation risk [10]. But, in the interest of cost, patient safety or compliance can omalizumab therapy be stopped or reduced? This study evaluated the latter by comparing the effects on asthma control of extending the intervals between omalizumab doses and reducing the dose of omalizumab in patients who had reached good asthma control.

Methods

This was a retrospective study conducted between 2009 and 2016 using data from the outpatient clinic of the allergy department of Charité—Universitätsmedizin, Berlin, Germany. A total of 37 patients (10 male and 27 female, median age at first injection 49 years with range 19–74 years) were included in the study. To be accepted, patients needed to have severe allergic asthma with symptoms during day and night, an impaired lung function (forced expiratory volume in one second [FEV1] < 80%), at least one sensitization to a perennial allergen and unstable disease though receiving maximum doses of inhaled corticosteroids.

Individual omalizumab dosing was based on age, body weight and serum-IgE levels according to European prescribing information [11]. After reaching a stable condition for at least 4 months, i. e. no exacerbations, FEV1% predicted >70%, asthma control test (ACT) ≥20 points, patients were assigned one of the groups, either extended interval between doses or dose reduction by one of the investigators/physicians. For the 26 patients in the extended interval group, dose intervals were extended by 1 week (2 to 3 weeks, 1 patient), 2 weeks (2 to 4 weeks, 1 patient and 4 to 6 weeks, 12 patients), 3 weeks (4 to 7 weeks, 6 patients), or even 4 weeks (2 to 6 weeks, 1 patient and 4 to 8 weeks, 5 patients). For the 11 patients in the dose reduction group, the monthly omalizumab dose was reduced by one third or as close as practically possible (900 to 600 mg, 2 patients; 600 to 450 mg, 8 patients and 450 to 300 mg, 1 patient).

The primary outcome was the number of patients in whom asthma control was lost. Loss of asthma control was defined a decrease in FEV1 ≥ 15%, a decline of ≥ 5 points in asthma control test or the need of additional medical therapy for exacerbation.

All data are expressed as median with range and significance of group differences tested using the Mann Whitney U test. The difference between two the groups in the number of patients losing asthma control was tested using the log-rank test. A probability of P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant for all calculations.

This study was approved by the responsible ethics committee of Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Germany and followed Good Clinical Practice guidelines and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

The demographics for the patients assigned to the extended dose interval and the dose reduction groups are shown in Table 1. As may be seen, there were no differences between groups in the gender distribution, age or duration of asthma. However, the serum IgE levels were higher and the predicted FEV1 lower in the dose reduction group suggesting their asthma to be more severe. The greater severity of this group was confirmed by their requiring higher omalizumab doses.

Following initial treatment with omalizumab, asthma was clinically under control in all patients with FEV1 and ACT values being greatly improved. Interestingly, however, although the FEV1 values of the two groups were numerically similar, statistically those of the extended dose interval group were significantly higher.

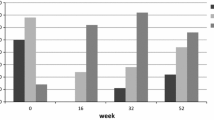

Following extension of the omalizumab dose interval as defined above, the asthma of 19 of the 26 patients (73%) remained in control for as long as observations were made (Fig. 1). This was a median of 16 months (range 7–39 months). Loss of asthma control occurred in only 7 patients (27%). In contrast, all 11 (100%) patients in the dose reduction group lost asthma control. The log-rank test showed that the difference in the number of patients losing asthma control was statistically significant (P < 0.001).

The time to loss of asthma control in the two groups was significantly slower (P = 0.047) in the extended dose interval than in the dose reduction group. In the extended dose interval group, the median time for loss of control in the seven patients was 8 months (range 5–35 months). In contrast, the time to loss of control after dose reduction was rapid in all but one patient (median 2 months, range 1–44 months). The individual times were 1 month (n = 2), 2 months (n = 4), 3 months (n = 2), 4 months (n = 2) and 43 months (n = 1).

Discussion

This study has shown clearly that in patients in whose asthma has been controlled by omalizumab for a prolonged period, extending the dose interval led to better asthma control than reducing the dose of omalizumab.

A large multicentre study of persistence of response after long-term omalizumab therapy has compared the effects of withdrawing from long-term treatment [10]. The results showed that asthma exacerbations occurred in 52% of patients withdrawing from therapy compared with 33% of individuals continuing therapy. Also, the time to the first exacerbation was significantly shorter in the patients discontinuing therapy. In a survey of 24 lung specialists [12], loss of asthma control was documented in 56% with a median interval between discontinuation and loss of control of 13.0 months. In contrast, Nopp and colleagues [13] reported that 12 of 18 adult atopic subjects treated with omalizumab for 6 years remained clinically stable for up to 3 years after omalizumab discontinuation. As a consequence, it is clear that cessation of omalizumab therapy will cause loss of asthma control in some but not all individuals.

Studies involving a reduction in the overall omalizumab dose load by prolonging the interval between doses have rarely been performed. In one study [14] clinical efficacy of omalizumab was maintained in 29 of 31 (94%) patients with extension of dosing intervals. Included were not only patients suffering from asthma, but also from urticaria, angioedema and atopic dermatitis. In a another study [15], increasing dose intervals from 1 to 16 weeks led to normal pulmonary function values in 44% compared with 85% of patients who continued with their initial interval. In our study, extending the dose interval by approximately one third led to loss of asthma control in only 27% of patients while lowering the dose by approximately one third caused 100% of the patients to lose asthma control.

The strength of this study is that it was a real study rather than a clinical trial. Also, although not being blinded, neither physicians nor patients could predict the outcome. The weaknesses were twofold. First, the patients in the dose reduction group were significantly, albeit not greatly, more severe. Second, it was a small study with limited patient numbers.

In conclusion, this small study shows that prolongation of the interval by approximately one third leads to maintenance of asthma control in the majority of patients. This has advantages for both the patients, who have to visit the clinic less often for injections, and to society as drug costs are lowered by one third.

References

Hekking PP, Wener RR, Amelink M, Zwinderman AH, Bouvy ML, Bel EH. The prevalence of severe refractory asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135:896–902.

Collaborators GCRD. Global, regional, and national deaths, prevalence, disability-adjusted life years, and years lived with disability for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and asthma, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet Respir Med. 2017;5:691–706.

Global Initiative for Asthma. Global strategy for asthma management and prevention 2018. 2018. http://ginasthma.org/2018-gina-report-global-strategy-for-asthma-management-and-prevention/. Accessed 18 Apr 2018.

Humbert M, Busse W, Hanania NA, Lowe PJ, Canvin J, Erpenbeck VJ, et al. Omalizumab in asthma: an update on recent developments. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2:525–536.e1.

Normansell R, Walker S, Milan SJ, Walters EH, Nair P. Omalizumab for asthma in adults and children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014; https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd003559.pub4.

Abraham I, Alhossan A, Lee CS, Kutbi H, MacDonald K. ‘Real-life’ effectiveness studies of omalizumab in adult patients with severe allergic asthma: systematic review. Allergy. 2016;71:593–610.

Alhossan A, Lee CS, MacDonald K, Abraham I. “Real-life” effectiveness studies of Omalizumab in adult patients with severe allergic asthma: meta-analysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:1362–1370.e2.

Licari A, Marseglia G, Castagnoli R, Marseglia A, Ciprandi G. The discovery and development of omalizumab for the treatment of asthma. Expert Opin Drug Discov. 2015;10:1033–42.

Lowe PJ, Renard D. Omalizumab decreases IgE production in patients with allergic (IgE-mediated) asthma; PKPD analysis of a biomarker, total IgE. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;72:306–20.

Ledford D, Busse W, Trzaskoma B, Omachi TA, Rosén K, Chipps BE, et al. A randomized multicenter study evaluating Xolair persistence of response after long-term therapy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;140:162–169.e2.

European Medicines Agency. Xolair, INN-omalizumab. 2009. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000606/WC500057298.pdf. Accessed 18 Apr 2018, Last updated: October 10 2016.

Molimard M, Mala L, Bourdeix I, Le Gros V. Observational study in severe asthmatic patients after discontinuation of omalizumab for good asthma control. Respir Med. 2014;108:571–6.

Nopp A, Johansson SG, Adédoyin J, Ankerst J, Palmqvist M, Oman H. After 6 years with Xolair; a 3-year withdrawal follow-up. Allergy. 2010;65:56–60.

Katz RM, Rafi AW, Do LT, Lin R, Mangat R, Azad N, Sender S. Efficacy of Omalizumab using extended dose intervals. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119(1 Suppl):S212.

Benouni S, Sheinkopf LE, Do LT, Rafi A, Katz RM. Extended Omalizumab dosage intervals and efficacy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(2 Suppl):AB3.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

G. Bölke, M.K. Church and K.-C. Bergmann declare that they have no competing interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bölke, G., Church, M.K. & Bergmann, KC. Comparison of extended intervals and dose reduction of omalizumab for asthma control. Allergo J Int 28, 1–4 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40629-018-0087-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40629-018-0087-6