Abstract

Purpose of Review

Previous studies have explored the links between problematic Internet use (PIU) or problematic smartphone use (PSU) and quality of life (QOL). In this systematic review, we (i) describe the instruments used to assess QOL or health-related quality of life (HRQOL) in these studies, (ii) critically examine the content validity of the instruments used, and (iii) examine the relationships between PIU, PSU, QOL, and HRQOL.

Recent Findings

We identified 17 PIU and 11 PSU studies in a systematic search. Evidence suggests that PIU and PSU negatively correlate with either QOL or HQOL and most of their domains (especially mental and physical health). Multiple instruments were used to assess QOL or HRQOL in these studies. Our analysis showed an important heterogeneity in the domains covered by these instruments.

Summary

Because of the widespread prevalence of PIU and PSU, which tend to be linked with lower QOL or HRQOL, in particular poor mental and physical health, a more systematic public health campaign is required to target the healthy use of these communication devices. Prevention programs should also target vulnerable individuals, focusing on the most affected domains of QOL and HRQOL (i.e., physical and psychological health). Among the existing instruments, the World Health Organization Quality of Life for adults and the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory for adolescents (aged 13–18 years) proved to be the most relevant, although new measurement instruments are needed to target domains that are specifically relevant in the context of PIU and PSU (e.g., physical and psychological health domains such as sleep, loneliness, and quality of familial relations).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The use of the Internet and smartphones has become a global phenomenon. Digital technology advancements have resulted in a wide range of applications, including improved communication, health, education, and leisure. Nonetheless, during the last two decades, a growing number of studies reported links between problematic or uncontrolled digital technology use and various indices of psychological and health problems [1–3]. Moreover, for a minority of vulnerable persons, excessive use of online applications (such as online video games, online sexual activities, on-demand streaming platforms, and social network sites) can become problematic and engender negative consequences and functional impairment [4, 5].

Internet and smartphone-mediated problematic online behaviors have been conceptualized within a spectrum of related conditions associated with both shared and unique features and risk factors [6, 7]. It was also proposed that Internet use disorders should be considered according to the devices used (i.e., mobile versus non-mobile devices), as some online activities are mainly performed through one type of device (e.g., instant messaging services like WhatsApp), whereas other online activities can be performed through both mobile and non-mobile devices (e.g., videogames) [8]. Accordingly, PIU and PSU overlap to some degree. Behavioral problems associated with the problematic use of digital technologies are often conceptualized as addictive disorders within a biomedical framework [9–10], although competing etiological models have been proposed. In particular, it has been suggested that these problematic behaviors can reflect impulse-control or obsessive-compulsive disorders, or constitute maladaptive coping displayed to regulate negative mood states or to face conditions such as anxiety or mood disorders [12••, 13].

Previous research has shown that problematic Internet use (PIU) and problematic smartphone use (PSU) are negatively associated with global life satisfaction [14, 15] and health-related quality of life (HRQOL) [16, 17]. However, this literature merely focused on determining prevalence rates and correlates (e.g., psychosocial variables) of “addictive” patterns of use (e.g., associated with symptoms of loss of control, or with tolerance-like or withdrawal-like symptoms). Indeed, previous studies often reported prevalence rates for various online problematic behaviors without considering whether the targeted condition was or was not associated with negative consequences or functional impairment. This issue is especially relevant in the context of technology use, which has become ubiquitous, and ignoring it risks pathologizing normal behavior or intensive but healthy usage patterns [12••, 18••], as reflected by the elevated prevalence rates often reported in the literature (e.g., exceeding 5% or even 10% in some cases). When more stringent criteria are applied and negative consequences or functional impairment are taken as a prerequisite to diagnose the condition, the reported prevalence rates diminish (e.g., 1–2% for problematic online gaming [19]).

As the majority of investigators who studied PIU and PSU in previous work did not take into account related negative consequences or functional impairment, we decided to systematically review the available evidence regarding the relationships between these problematic behaviors and quality of life (QOL), assuming that the presence of problematic or pathological behavior would be associated with poor QOL. The World Health Organization defines QOL as “an individual’s perception of their position in life concerning their goals, expectations, standards, and concerns in the context of the culture and value systems in which they live [20].” It is a broad concept influenced in a complex way by a person’s physical health, psychological state, level of independence, social relationships, and relationship to key features of their environment [21]. Instruments that assess QOL can be divided into (i) general QOL instruments that do not specifically focus on the subjective health state and (ii) instruments that assess HRQOL that classically focus on four specific domains: physical, physical well-being, psychological state, and social relations [22].

Several definitions of HRQOL have been proposed [23•], and in the present review, we consider HRQOL to reflect aspects of self-perceived well-being and perceived physical and mental health that are related to or affected by the presence of disease or treatment [24]. In contrast, QOL corresponds to the subjective feeling of satisfaction about important life domains [24]. The terms HRQOL and QOL are frequently used interchangeably [23•], and the medical literature has debated how to conceptualize and measure HRQOL since the 1960s [25], as it is a complex construct with no universally accepted definition [26]. However, it is agreed that it should not be defined as the absence of disease or disorder, but rather from a more holistic perspective that includes physical, psychological, emotional, and social factors.

In the present systematic review, we thus (i) describe the instruments used to assess QOL or HRQOL in PIU and PSU research, (ii) critically examine the content validity of the instruments used in these studies, and (iii) examine relationships between PIU, PSU, QOL, and HRQOL.

Method

Inclusion Criteria

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement guidelines for systematic reviews [27, 28]. The inclusion criteria for eligible studies in the present systematic review were as follows: (i) studies published in scientific journals from 2011 to December 2021 (a 10-year period was considered to increase the potential number of studies included in this systematic review), (ii) studies written in English, and (iii) studies reporting the association between QOL or HRQOL and PIU or PSU. Moreover, studies that focused on specific online activities (e.g., social network use, online gambling, video gaming) were excluded, as the present review focused on the broader PIU and PSU constructs.

Search Strategy and Study Selection

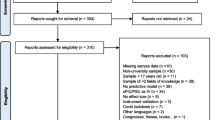

In the literature search, we aimed at identifying original empirical studies that reported correlations between PIU or PSU and QOL or HRQOL in the electronic databases Science Direct, PsycNET, and PubMed.

Two systematic literature searches were performed, one for PIU and one for PSU. Regarding PIU, the following terms were used: “Internet AND use disorder (overuse OR addict* OR abuse OR use severity OR problematic OR dependence) AND (“Qol” OR “quality of life”).” Regarding PSU, the following terms were used: “smartphone (cellphone OR mobile phone) AND use disorder (overuse OR addict* OR abuse OR use severity OR problematic OR dependence) AND (“Qol” OR “quality of life”)”. The following number of articles were identified for PIU: Science Direct (438), PsycNET (221), and PubMed (549). The following number of articles were identified for PSU: Science Direct (102), PsycNET (1), and PubMed (46). Study selection was performed in two successive stages. First, the titles and abstracts of all potentially relevant articles were carefully scrutinized for eligibility according to inclusion criteria. Second, the full texts of the studies retained at the first stage were scrutinized for eligibility based on the same criteria. The PRISMA flowcharts illustrating the study selection process for each literature search are reported in Figs. 1 and 2.

Data Extraction

The following data were extracted from the full text of the articles: country, sample size, age of the participants, study design, study goal, measurement instruments used for PIU or PSU and QOL or HRQOL, and study results. In the present study, we used the term “case-control” study to describe a study in which groups of participants were compared based on a pre-established criterion (e.g., the cutoff score on a specific scale). Information about content coverage (domains covered by the instruments) were extracted and analyzed. This information was used to establish content validity, that is, the extent to which a measure represents all facets of a given construct (i.e., sufficiently covers the measured construct). Poor content validity generally implies that the measurement instrument assesses too narrowly a construct. In our case, an instrument with poor content validity would be one that does not assess important aspects of QOL or HRQOL that might be affected by PIU or PSU.

Results

This systematic review retained 17 studies for PIU that included 34,615 participants and 11 studies for PSU that included 204,118 participants. Six of 17 PIU studies (35.29%) and four of 11 PSU studies (36.36%) assessed HRQOL and the remainder of the studies examined QOL. All of the retained studies reported a negative correlation between QOL or HRQOL and PIU or PSU. The correlations reported in these studies ranged from r = −.13 to r = −.46 for PIU and r = −.09 to r = −.50 for PSU.

Measurement Instruments Used to Assess QOL or HRQOL

The measurement instruments used in the retained studies differed in terms of the number of domains covered. Table 1 describes these instruments. Nine different psychometrically validated instruments were identified. A few instruments were composed of a series of items created in the context of a specific study and are not considered further in the present systematic review. The most used measurement instruments in PIU studies were the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL) \((n=6),\) followed by the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory (PedsQL) \((n=3)\) and the 12-item Short Form Survey (SF-12) \(\left(n=3\right);\) the most used measurement instruments in PSU studies were the WHOQOL \((n=3)\) and the KIDSCREEN (\(n=2\)). None of the instruments used in the studies retained were specifically designed to assess QOL or HRQOL in the context of PIU or PSU.

All domains assessed by QOL or HRQOL instruments in the retained studies are described in Tables 1 and 2.

The WHOQOL was the most frequently used instrument in the retained studies. Domains and facets incorporated in this comprehensive instrument include physical health (activities of daily living, dependence on medicinal substances and medical aids, energy and fatigue, mobility, pain and discomfort, sleep and rest, work capacity), psychological health (bodily image and appearance, negative affect, positive affect, self-esteem, spirituality/religion/personal beliefs, learning, memory and concentration), quality of social relationships (personal relationships, social support, sexual activity), and quality of environment (financial resources, freedom, physical safety and security, health and social care: accessibility and quality, home environment, opportunities for acquiring new information and skills, participation in and opportunities for recreation or leisure activities, physical environment [pollution/noise/traffic/climate], transport).

In order to synthetize and compare the results of the studies retained in the present systematic review, we reclassified the domains covered by the measurement instruments used into six different domains and 14 subdomains: physical health (daily activities, energy and fatigue, bodily pain, sleep and rest), psychological health (negative and positive effect, bodily image and appearance, loneliness, memory and concentration), relations (family relations, social relations), school performance, quality of environment (physical environment, financial problems, security, health and social care), and satisfaction with life, as illustrated in Table 2. This classification was conducted in order to identify specific categories for domains established as critical in the context of PIU and PSU, such as perceived loneliness or familial relationships.

An analysis of the domains covered by these instruments shows high heterogeneity. For instance, physical health is not assessed by the My Life as a Student questionnaire and the Subjective QOL questionnaire. Although all scales that we identified assessed psychological health, the specific aspects of psychological health that were measured differed among scales. For example, negative and positive affect (e.g., anxiety and depression) were assessed by almost all of the instruments, but loneliness was considered only in the KIDSCREEN and the WHOQOL.

Measurement Instruments Used to Assess PIU and PSU

The studies included in the current systematic review mainly assessed PIU with Young’s Internet addiction test (YIAT) [36], Chen Internet addiction scale (CIAS) [37], and the Generalized Problematic Internet Use (GPIUS) [38]. For PSU, the most widely used scales were the smartphone addiction short version (SAS-SV) [39], the mobile phone problem use scale (MPPUS) [40], and the mobile phone addiction index (MPAI) [41]. These scales have been found to present with good psychometric properties [42, 43].

Relationships Between PIU and QOL or HRQOL

Retained articles for PIU are synthesized in Table 3. Most studies that used the WHOQOL showed negative correlations between PIU and QOL or HRQOL domains [14, 44, 45]. Interestingly, a few studies considered more than a global score of QOL or HRQOL with the WHOQOL and reported that some domains are not linked to PIU, for example, the environmental domain [46, 47]. On the whole, studies that used the WHOQOL consistently showed that PIU is negatively correlated with QOL or HRQOL.

Studies conducted with other instruments globally reproduced the same patterns of results. Studies that used the PedsQL generally showed a negative association with domains of the HRQOL or QOL [48, 49]. Yet, a study by Cruz et al. [50] found no correlation with social functioning. Studies that used the SF-12 showed that physical and psychological domains are both affected [51, 56], except for physical pain [59].

Relationships Between PSU and QOL or HRQOL

The articles retained for PSU are synthesized in Table 4. All of these studies reported a negative correlation between PSU and QOL or HRQOL. Studies that considered the various domains assessed by the WHOQOL showed that PSU is negatively correlated to all QOL domains assessed [60] and that the psychological domain is most affected [61].

Buctot and colleagues [17] also showed, using KIDSCREEN-27, that PSU is negatively correlated with several domains (physical health and psychological health, school environment) but unrelated to others (e.g., autonomy, parental, and peer support). Another study that used the SF-12 showed that PSU is associated with poor mental health but not physical health [69].

Discussion

In this systematic review, we synthesized the studies that explored the relationships between PIU or PSU and QOL or HRQOL and critically evaluated the measurement instruments used to assess QOL or HRQOL in these studies. Addressing this topic is warranted, as a substantial part of previous research explored PIU and PSU while not necessarily considering the negative consequences associated with Internet or smartphone use, thus potentially overpathologizing normal technology use [12••].

Here, we provided a summary of the measurement instruments used to assess QOL or HRQOL in existing studies and examined their content validity in the context of PIU and PSU. It might be that QOL and HRQOL instruments not specifically developed in the context of PIU and PSU research do not include domains that are particularly relevant to these problematic behaviors. Our analysis showed that there was an important heterogeneity in the domains covered by QOL and HRQOL instruments used in the retained studies. Moreover, different instruments can assess similar domains with diverging items, thus further complicating the comparison among studies. For example, four of the nine identified instruments (i.e., KIDSCREEN, PedsQL, My Life as a Student questionnaire, and the Subjective QOL questionnaire) evaluated the school domain, but with different items and concepts.

This review shows that WHOQOL for adults and PedsQL, which targets participants aged 13–18 years, are the most used measurement instruments. In terms of the classification of domains in the current systematic review, these instruments cover physical health, psychological health, social relations, quality of the environment, and satisfaction with life (WHOQOL), or physical health, psychological health, social relations, and school performance (PedsQL), making them the most convenient instruments at hand. Notably, some of the instruments identified in this systematic review and synthesized in Table 1 (including the most used instrument: WHOQOL) do not cover key domains such as familial relations, which is a crucial variable regarding PIU [70, 71]. Despite the content-coverage limitation described earlier, the QOL and HRQOL instruments used in the retained studies could be effective in measuring a change after intervention [72]. Clinical studies are indeed lacking, and it would be interesting to determine which domains of QOL and HRQOL might be affected by treatment programs or preventive actions. Further research could also overcome the content coverage problem identified in the current study with the development and validation of new instruments, potentially based on qualitative analysis conducted in individuals with PIU or PSU that has clear negative consequences and causes functional impairment.

All retained studies reported negative correlations between QOL or HRQOL and PIU or PSU. The majority of studies were published within the last 3 years, indicating recent research interest, likely fueled by clinical demand or by the recognition that PIU and PSU have become internationally relevant public health issues [3]. On the whole, existing evidence indicates a significant negative relationship between PIU or PSU and the psychological and physical domains of QOL or HRQOL, which is in line with a recent review of these relationships in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic [73]. However, the heterogeneity of the instruments used makes it difficult to compare other affected domains in the retained studies, such as environmental and social domains [14, 46, 47, 52, 74].

This systematic review comes with several limitations. First, the number of studies was relatively limited, and most were cross-sectional studies conducted with self-selected participants, thus hindering causal interpretation and compromising the representativeness of the findings. Given the public health relevance of technology-mediated problematic behaviors, future research in this field should be conducted in nationally representative samples or should follow longitudinal designs. Moreover, few studies have surveyed clinical participants or tested the impact of prevention or treatment approaches on QOL or HRQOL. Second, we considered only studies written in English, and it is possible that relevant literature published in other languages was neglected. Much research published in national East-Asian journals (e.g., Japanese, Korean, or Chinese journals) could have been relevant to the topic under study (see, e.g., Long et al. [75], for the necessity of considering such literature in the context of technology-mediated problematic behaviors). Third, most of the retained studies reported an overall correlation between PIU or PSU and QOL or HRQOL without giving detailed information on the specific domains affected. Fourth, recent research suggests that the terms “Internet addiction” and “smartphone addiction” might be deceptive. Indeed, these terms are umbrella constructs that encompass a wide range of potentially problematic technologically mediated behaviors involving various online activities [18••, 76, 77, 13], for which the Internet or a smartphone serves as the common vector or “delivery mechanism” [78, 79, 80]. According to these views, the focus must be on specific online activities, not on the medium through which they take place. Yet, for parsimony reasons, we decided not to include studies focusing on specific online activities (e.g., videogames or social network sites). This could have resulted in excluding potential relevant studies about QOL/HQOL and specific problematic online behaviors. Accordingly, it would be important to consider the evidence linking specific problematic online behaviors and QOL or HRQOL in future systematic literature reviews. That being said, it was also proposed that technology-mediated problematic behaviors are to be conceptualized within a spectrum of related disorders associated with both common and unique etiological factors [6, 7], implying that an analysis of their commonalities, as was done in the current systematic review, is also required.

Conclusion

Because of the widespread prevalence of PIU and PSU, which tend to be linked with lower QOL or HRQOL, in particular poor mental and physical health, promotion of a more systematic public health campaign is required to target the healthy use of these communication devices. Prevention programs should also target vulnerable individuals, focusing on the most affected domains of QOL or HRQOL (i.e., physical and psychological health). Among existing instruments, WHOQOL for adults and PedsQL for adolescents (aged 13–18 years) proved to be the most relevant, as shown from the results of this systematic review, although there is a need for new measurement instruments that target domains that are specifically relevant in the context of PIU and PSU (e.g., specific physical and psychological health domains such as sleep and loneliness, quality of familial relations).

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Kuss JD, Griffiths DM, Karila L, Billieux J. Internet addiction: a systematic review of epidemiological research for the last decade. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20(25):4026–52.

Van Den Brink W. ICD-11 Gaming disorder: needed and just in time or dangerous and much too early? Commentary on: scholars’ open debate paper on the World Health Organization ICD-11 Gaming Disorder proposal (Aarseth et al.). J Behav Addict. 2017;6(3):290–2.

World Health Organization. Public health implications of excessive use of the Internet, computers, smartphones and similar electronic devices: meeting report, Main Meeting Hall, Foundation for Promotion of Cancer Research, National Cancer Research Centre, Tokyo, Japan. 2015. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/184264. 27-29 August.

Billieux J, King DL, Higuchi S, Achab S, Bowden-Jones H, Hao W, ... Poznyak V. Functional impairment matters in the screening and diagnosis of gaming disorder: commentary on: scholars’ open debate paper on the World Health Organization ICD-11 Gaming Disorder proposal (Aarseth et al.). J Behav Addict. 2017;6(3):285–9.

Brand M, Rumpf HJ, Demetrovics Z, MÜller A, Stark R, King DL, ... Potenza MN. Which conditions should be considered as disorders in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) designation of “other specified disorders due to addictive behaviors”? J Behav Addict. 2020.

Baggio S, Starcevic V, Studer J, Simon O, Gainsbury SM, Gmel G, Billieux J. Technology-mediated addictive behaviors constitute a spectrum of related yet distinct conditions: a network perspective. Psychol Addict Behav. 2018;32(5):564–72.

Starcevic V, Billieux J. Does the construct of Internet addiction reflect a single entity or a spectrum of disorders? Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2017;14(1):5–10.

Montag C, Wegmann E, Sariyska R, Demetrovics Z, Brand M. How to overcome taxonomical problems in the study of Internet use disorders and what to do with “smartphone addiction”? J Behav Addict. 2021;9(4):908–14.

Block JJ. Issues for DSM-V: Internet addiction. Am Psychiatric Assoc. 2008;165(3):306–7.

Choliz M. Mobile phone addiction: a point of issue. Addiction. 2010;105(2):373–4.

Petry NM, O’Brien CP. Internet gaming disorder and the DSM-5. Addiction. 2013;108(7):1186–7.

•• Kardefelt‐Winther D, Heeren A, Schimmenti A, van Rooij A, Maurage P, Carras M, ... Billieux J. How can we conceptualize behavioural addiction without pathologizing common behaviours? Addiction. 2017;112(10):1709–15. (This article is the first one proposing an operational definition of behavioral addiction, together with a number of exclusion criteria, to avoid pathologizing normal behavior.)

Starcevic V, Aboujaoude E. Internet addiction: reappraisal of an increasingly inadequate concept. CNS Spectr. 2017;22(1):7–13.

Chern K-C, Huang J-H. Internet addiction: associated with lower health-related quality of life among college students in Taiwan, and in what aspects? Comput Human Behav. 2018;84:460–6.

Pearson AD, Young CM, Shank F, Neighbors C. Flow mediates the relationship between problematic smartphone use and satisfaction with life among college students. J Am Coll Health. 2021;1–9.

Tran BX, Huong LT, Hinh ND, Nguyen LH, Le BN, Nong VM, ... Ho R. A study on the influence of Internet addiction and online interpersonal influences on health-related quality of life in young Vietnamese. BMC Public Health. 2017;17(1):138.

Buctot DB, Kim N, Kim JJ. Factors associated with smartphone addiction prevalence and its predictive capacity for health-related quality of life among Filipino adolescents. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2020;110: 104758.

•• Billieux J, Maurage P, Lopez-Fernandez O, Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD. Can disordered mobile phone use be considered a behavioral addiction? An update on current evidence and a comprehensive model for future research. Curr Addict Rep. 2015;2(2):156–62. (This study proposed a comprehensive pathways model to explain various types of problematic mobile phone use. Each pathway is underlain by specific etiological mechanisms and associated with various risk and protective factors.)

Stevens MW, Dorstyn D, Delfabbro PH, King DL. Global prevalence of gaming disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Aust NZ J Psychiatry. 2020;55(6):553–68.

Whoqol Group. Measuring quality of life. Geneva: the World Health Organization. 1997:1-3. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/63482.

Szabo S. The World Health Organization Quality of life (WHOQOL) assessment instrument. In: Spilker B, editor. Quality of life and pharmacoeconomics in clinical trials. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1996. p. 355–62.

Leplège A. Les mesures de la qualité de vie. Paris: Presses Universitaires de France; 1999.

• Karimi M, Brazier J. Health, health-related quality of life, and quality of life: what is the difference? Pharmacoeconomics. 2016;34(7):645–9. (This paper reviews the history and definitions of the terms QOL and HRQOL and the way these terms have been used in the scientific literature. It gives a comprehensive overview of these terms and the available measurement instruments.)

Ebrahim S. Clinical and public health perspectives and applications of health-related quality of life measurement. Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(10):1383–94.

Elkinton JR. Medicine and the quality of life. Ann Intern Med. 1966;64(3):711–4.

Wallander JL, Koot HM. Quality of life in children: a critical examination of concepts, approaches, issues, and future directions. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;45:131–43.

Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, Mulrow C, Gøtzsche PC, Ioannidis JP, ... Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34.

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, ... Stewart LA. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):1–9.

Ravens-Sieberer U. The Kidscreen questionnaires: quality of life questionnaires for children and adolescents; handbook. Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers; 2006.

The EuroQol Group. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199–208.

Ware JE Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33.

Scarpelli AC, Paiva SM, Pordeus IA, Varni JW, Viegas CM, Allison PJ. The Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory™(PedsQL™) family impact module: reliability and validity of the Brazilian version. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2008;6(1):35.

Flanagan JC. Measurement of the quality of life: Current state of the art. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1982;63:56–59.

Nota L, Soresi S, Ferrari L, Wehmeyer ML. A multivariate analysis of the self-determination of adolescents. J Happiness Stud. 2011;12(2):245–66.

Zaohuo C, Beiling G, Jian P. The inventory of subjective life quality for child and adolescent: development, reliability, and validity. Chin J Clin Psychol. 1998;6(1):11–6.

Young KS. Caught in the Net: How to recognize the signs of Internet addiction and a winning strategy for recovery. New York: Wiley; 1998.

Chen S, Weng L, Su Y, Wu H, Yang P. Development of a Chinese Internet addiction scale and its psychometric study. Chin J Psychol. 2003;45(3):279–94.

Caplan SE. Theory and measurement of generalized problematic Internet use: A two-step approach. Comput Hum Behav. 2010;26:1089–97.

Kwon M, Lee JY, Won WY, Park JW, Min JA, Hahn C, Gu X, Choi J-H, Kim DJ. Development0 and validation of a Smartphone Addiction Scale (SAS). PLoS ONE. 2013;8(2): e56936.

Bianchi A, Phillips JG. Psychological predictors of problem mobile phone use. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2005;8:39–51.

Leung L. Linking psychological attributes to addiction and improper use of the mobile phone among adolescents in Hong Kong. J Child Media. 2008;2:93–113.

Laconi S, Rodgers RF, Chabrol H. The measurement of Internet addiction: a critical review of existing scales and their psychometric properties. Comput Hum Behav. 2014;41:190–202.

Harris B, Regan T, Schueler J, Fields SA. Problematic mobile phone and smartphone use scales: a systematic review. Front Psychol. 2020;11:672.

Cai H, Xi HT, Zhu Q, Wang Z, Han L, Liu S, ... Xiang YT. Prevalence of problematic Internet use and its association with quality of life among undergraduate nursing students in the later stage of COVID‐19 pandemic era in China. Am J Addict. 2021;30(6):585–92.

Xu DD, Lok KI, Liu HZ, Cao XL, An FR, Hall BJ, ... Xiang YT. Internet addiction among adolescents in Macau and mainland China: prevalence, demographics and quality of life. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):1–10.

Fatehi F, Monajemi A, Sadeghi A, Mojtahedzadeh R, Mirzazadeh A. Quality of life in medical students with Internet addiction. Acta Med Iran. 2016;54(10):662–6.

Lu L, Xu DD, Liu HZ, Zhang L, Ng CH, Ungvari GS, ... Xiang YT. Internet addiction in Tibetan and Han Chinese middle school students: prevalence, demographics and quality of life. Psychiatry Res. 2018;268:131–6.

Barayan SS, Al Dabal BK, Abdelwahab MM, Shafey MM, Al Omar RS. Health-related quality of life among female university students in Dammam district: is Internet use related? J Family Community Med. 2018;25(1):20–8.

Cam HH, Top FU. Prevalence and risk factors of problematic Internet use and its relationships to the self-esteem and health-related quality of life: data from a high-school survey in Giresun Province Turkey. J Addict Nurs. 2020;31(4):253–60.

Cruz FAD, Scatena A, Andrade ALM, Micheli DD. Evaluation of Internet addiction and the quality of life of Brazilian adolescents from public and private schools. Estudos de Psicologia (Campinas). 2018;35(2):193–204.

Eliacik K, Bolat N, Koçyiğit C, Kanik A, Selkie E, Yilmaz H, ... Dundar BN. Internet addiction, sleep and health-related life quality among obese individuals: a comparison study of the growing problems in adolescent health. EatWeight Disord. 2016;21(4):709–17.

Tingting GAO, Xiang YT, Zeying QIN, Yueyang HU, Songli MEI. Internet addiction and quality of life in college students: a multiple mediation analysis. Iran J Public Health. 2019;48(11):2094–6.

Gao L, Gan Y, Whittal A, Lippke S. Problematic Internet use and perceived quality of life: findings from a cross-sectional study investigating work-time and leisure-time Internet use. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(11):4056.

Huang Y, Xu L, Mei Y, Wei Z, Wen H, Liu D. Problematic Internet use and the risk of suicide ideation in Chinese adolescents: a cross-sectional analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2020;290: 112963.

Xie YX. Study on establishment norm of suicide ideation and its influential factors among high school students in Chongqing Province. Southwestern University; 2013.

Karimy M, Parvizi F, Rouhani MR, Griffiths MD, Armoon B, Fattah Moghaddam L. The association between Internet addiction, sleep quality, and health-related quality of life among Iranian medical students. J Addict Dis, 2020: p. 1–9.

Machimbarrena JM, González-Cabrera J, Ortega-Barón J, Beranuy-Fargues M, Álvarez-Bardón A, Tejero B. Profiles of problematic Internet use and its impact on adolescents’ health-related quality of life. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16(20):3877.

Pontes HM, Szabo A, Griffiths MD. The impact of Internet-based specific activities on the perceptions of Internet addiction, quality of life, and excessive usage: a cross-sectional study. Addict Behav Rep. 2015;1:19–25.

Takahashi M, Adachi M, Nishimura T, Hirota T, Yasuda S, Kuribayashi M, Nakamura K. Prevalence of pathological and maladaptive Internet use and the association with depression and health-related quality of life in Japanese elementary and junior high school-aged children. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2018;53(12):1349–59.

Li L, Lok GK, Mei SL, Cui XL, Li L, Ng CH, ... Xiang YT. The severity of mobile phone addiction and its relationship with quality of life in Chinese university students. PeerJ. 2020;8:e8859.

Awasthi S, Kaur A, Solanki HK, Pamei G, Bhatt M. Smartphone use and the quality of life of medical students in the Kumaun Region Uttarakhand. J Family Med Prim Care. 2020;9(8):4252–8.

Demir YP, Sumer MM. Effects of smartphone overuse on headache, sleep and quality of life in migraine patients. Neurosciences (Riyadh). 2019;24(2):115–21.

Gao T, Xiang YT, Zhang H, Zhang Z, Mei S. Neuroticism and quality of life: multiple mediating effects of smartphone addiction and depression. Psychiatry Res. 2017;258:457–61.

Gao Q, Sun R, Fu E, Jia G, Xiang Y. Parent–child relationship and smartphone use disorder among Chinese adolescents: the mediating role of quality of life and the moderating role of educational level. Addict Behav. 2020;101: 106065.

Hughes N, Burke J. Sleeping with the frenemy: how restricting ‘bedroom use’ of smartphones impacts happiness and wellbeing. Comput Human Behav. 2018;85:236–44.

Jeong YW, Han YR, Kim SK, Jeong HS. The frequency of impairments in everyday activities due to the overuse of the Internet, gaming, or smartphone, and its relationship to health-related quality of life in Korea. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):1–16.

Mascia ML, Agus M, Penna MP. Emotional intelligence, self-regulation, smartphone addiction: which relationship with student well-being and quality of life? Front Psychol. 2020;11:375.

Mireku MO, Barker MM, Mutz J, Dumontheil I, Thomas MS, Röösli M, ... Toledano MB. Night-time screen-based media device use and adolescents’ sleep and health-related quality of life. Environ Int. 2019;124:66–78.

Miri M, Tiyuri A, Bahlgerdi M, Miri M, Miri F, Salehiniya H. Mobile addiction and its relationship with quality of life in medical students. Clin Epidemiol Glob Health. 2020;8(1):229–32.

Nielsen P, Favez N, Liddle H, Rigter H. Linking parental mediation practices to adolescents’ problematic online screen use: a systematic literature review. J Behav Addict. 2019;8(4):649–63.

Nielsen P, Favez N, Rigter H. Parental and family factors associated with problematic gaming and problematic Internet use in adolescents: a systematic literature review. Curr Addict Rep. 2020;7:365–86.

Bonfils NA, Aubin HJ, Benyamina A, Limosin F, Luquiens A. Quality of life instruments used in problem gambling studies: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2019;104:58–72.

Masaeli N, Farhadi H. Prevalence of Internet-based addictive behaviors during COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review. J Addict Dis. 2021;39(4):468–88.

Wang W, Zhou DD, Ai M, Chen XR, Lv Z, Huang Y, Kuang L. Internet addiction and poor quality of life are significantly associated with suicidal ideation of senior high school students in Chongqing China. PeerJ. 2019;7: e7357.

Long J, Liu T, Liu Y, Hao W, Maurage P, Billieux J. Prevalence and correlates of problematic online gaming: a systematic review of the evidence published in Chinese. Curr Addict Rep. 2018;5(3):359–71.

Andreassen CS, Billieux J, Griffiths MD, Kuss DJ, Demetrovics Z, Mazzoni E, Pallesen S. The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: a large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychol Addict Behav. 2016;30(2):252–62.

Király O, Griffiths MD, Urbán R, Farkas J, Kökönyei G, Elekes Z, ... Demetrovics Z. Problematic Internet use and problematic online gaming are not the same: findings from a large nationally representative adolescent sample. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2014;17(12):749–54.

Yellowlees PM, Marks S. Problematic Internet use or Internet addiction? Comput Human Behav. 2007;23(3):1447–53.

Griffiths M. Does Internet and computer “addiction” exist? Some case study evidence. CyberPsychol Behav. 2000;3(2):211–8.

Shaffer HJ, Hall MN, Bilt JV. “Computer addiction”: a critical consideration. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70(2):162–8.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Lausanne

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

This article does not involve any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors of this review.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. This article has been edited by Section Editor Hans Jürgen-Rumpf, as Joël Billieux is a Section Editor for the topical collection Internet-Use Disorders.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Internet Use Disorders

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Masaeli, N., Billieux, J. Is Problematic Internet and Smartphone Use Related to Poorer Quality of Life? A Systematic Review of Available Evidence and Assessment Strategies. Curr Addict Rep 9, 235–250 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-022-00415-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-022-00415-w