Abstract

This article queries whether and to what extent works produced with the aid of AI systems – AI-assisted output – are protected under EU copyright standards. We carry out a doctrinal legal analysis to scrutinise the concepts of “work”, “originality” and “creative freedom”, as well as the notion of authorship, as set forth in the EU copyright acquis and developed in the case-law of the Court of Justice. On this basis, we develop a four-step test to assess whether AI-assisted output qualifies as an original work of authorship under EU law, and how the existing rules on authorship may apply. Our conclusion is that current EU copyright rules are generally suitable and sufficiently flexible to deal with the challenges posed by AI-assisted output.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

As artificial intelligence (AI) is making inroads into the realm of culture, the alleged creative powers of intelligent machines are reaching almost mythical proportions. Spectacular examples abound, ranging from the impressive The Next Rembrandt,Footnote 1 a Rembrandt-style portrait created with the help of algorithms, to the uncannily well-crafted translations by DeepL.Footnote 2 Indeed, AI-assisted creation nowadays encompasses almost the entire spectrum of subject matter listed in Art. 2(1) of the Berne Convention.

The creative powers of advanced AI systems have led some scholars to conclude that the results of artificial creation cannot be protected by copyright, since human beings have lost control of the creative process.Footnote 3 Some writers, therefore, argue for the introduction of special neighbouring rights to protect “authorless” AI-generated output against misappropriation.Footnote 4 But is this assumption correct? Or can AI-assisted output qualify for copyright protection, despite the increasingly important role that machines play in its creation?

To be sure, this is not an entirely new question. As early as the 1960s scholars have grappled with questions related to computer-generated works.Footnote 5 With the rise of AI, in particular machine learning techniques, the issue has gained momentum and inspired a vast new body of legal scholarship in recent years.Footnote 6

It is beyond the scope of this article to provide a detailed definition of AI systems – something we have endeavoured to do elsewhere.Footnote 7 We also refer to the abundant literature on the subject, some of it in the field of intellectual property.Footnote 8 Moreover, multiple definitions have been advanced at EU level, in various initiatives from the European Parliament, the European Commission, and their research services.Footnote 9 In this article, we rely on the broad definition advanced in the Commission’s 2021 proposal for an AI Act.Footnote 10 According to this definition, which builds on previous policy work by the High-Level Expert Group on AI,Footnote 11 an AI system means “software that is developed with one or more of the techniques and approaches listed in Annex I and can, for a given set of human-defined objectives, generate output such as content, predictions, recommendations, or decisions influencing the environments they interact with”.Footnote 12 Annex I lists various techniques and approaches, including: (a) different types of machine learning (supervised, unsupervised and reinforcement) using a variety of different methods (e.g. deep learning); (b) logic- and knowledge-based approaches; and (c) statistical approaches.Footnote 13

This article poses the question whether and to what extent works produced with the aid of AI systems – in short, AI-assisted output – are protected under EU copyright standards. “AI-assisted output” is intended to refer to all output, applications or works generated by or with the assistance of AI systems, as defined above. What is central to the following analysis is not the intelligent machine, but the role of human beings in the AI-assisted creative process. Is this role sufficient to elevate the result of this process, the AI-assisted output, to the status of a copyright-protected work?

This article is based on a study commissioned by the European Commission,Footnote 14 the conclusions of which inform the policy position on AI-assisted creation adopted by the Commission in its 2020 IP Action Plan.Footnote 15 This follows several policy initiatives at EU level on the intersection of AI and copyright, including on the protection of AI output.Footnote 16 The analysis presented here is largely doctrinal. Normative questions about the most desirable protection regime for AI-assisted output are not addressed. Neither do we examine alternative regimes available under current law, such as neighbouring rights or unfair competition law.Footnote 17

To begin with, in Sect. 2 we present a general overview of the current framework of EU copyright law as it pertains to copyright protected “works”. In Sect. 3, we turn to the core question whether and under what conditions AI-assisted output qualifies as a “work” protected under harmonised copyright standards. To this end, we closely scrutinise the notions of “work”, “originality” and “creative freedom”, as developed in the case-law of the CJEU. As we shall demonstrate, the CJEU’s decisions in Painer and Football Dataco offer important clues in answering our research question.Footnote 18 In Sect. 4 we address the issue of authorship of AI-assisted output, which is intimately linked to that of the notion of “work”. Nevertheless, since this notion has so far remained largely unharmonised, nationally divergent solutions have been developed, such as the rules on authorship of computer-generated works in UK and Irish copyright law.Footnote 19 In Sect. 5 we present our conclusions.

2 The Evolving EU Standard of “Work”

The current EU copyright framework is mostly silent on questions of copyright subject matter and authorship. Despite extensive copyright harmonisation, no single directive harmonises the concept of the work of authorship in general terms. Article 1 of the Term DirectiveFootnote 20 comes fairly close to a general definition by referring to copyright subject matter as “a literary or artistic work within the meaning of Art. 2 of the Berne Convention”.Footnote 21 In its jurisprudence, the CJEU similarly seeks guidance from Art. 2(1) of the Berne Convention, which, through its incorporation by reference into the TRIPS Agreement and the WCT,Footnote 22 has become part of the EU legal order.Footnote 23

The EU acquis expressly harmonises three – or possibly four – specific categories of copyright-protected subject matter: computer programmes, databases, photographs, and (possibly) works of visual art.Footnote 24 Each of these qualifies as a protected work if it is “original in the sense that it is the author’s own intellectual creation”. In its 2009 Infopaq judgment, the CJEU extrapolated from this piecemeal harmonisation a general, autonomous concept under EU law of the work as “the author’s own intellectual creation”.Footnote 25 This has been confirmed in later judgments, most recently in Levola Hengelo, Funke Medien, Cofemel and Brompton Bicycle.Footnote 26

2.1 Production in the Literary, Scientific or Artistic Domain

From the definition of “work” in Art. 2(1) of the Berne Convention follows a general requirement that works be produced within the “literary, scientific or artistic domain”. Whereas some scholars have given normative meaning to this categorical notion,Footnote 27 the CJEU has not clearly embraced this “domain test” as a separate criterion. In Premier League the Court denied copyright to sporting events for the reason that they “cannot be regarded as intellectual creations classifiable as works”,Footnote 28 which possibly suggests an application of the domain test. However, elsewhere in the judgment it transpires that the Court’s exclusion of sporting events is based on the lack of originality.Footnote 29 Similarly, in Levola Hengelo the Court could have relied on this test to deny “work” status to the taste of a food product. Instead, it formulated a criterion of “identifiable” expression to achieve the same result.Footnote 30 It is therefore not clear whether this general test is incorporated into EU copyright law.

2.2 Human Intellectual Effort

Like the Berne Convention, the EU copyright acquis is primarily grounded in the tradition of author’s rights (droit d’auteur): copyright protects original expression directly emanating from a human creator. The Berne Convention does not define the “author” of a work, leaving this to the contracting parties, but its text and historical context strongly suggest that “author” and “authorship” for the purposes of the Convention refer to the natural person who created the work.Footnote 31 This implies that copyright protection initially vests in human authors.Footnote 32 This is confirmed by the Convention’s ubiquitous references to the “author” as the originator of works and the beneficiary of protection. The Convention’s provision on moral rights (Art. 6bis) that are expressly granted to “authors” underscores that its minimum standards of copyright protection are triggered only by acts of human creation.

Although EU copyright law nowhere expressly states that copyright requires a human creator, its “anthropocentric” focus (on human authorship) is self-evident in many aspects of the law.Footnote 33 For one thing, the CJEU’s case-law on originality, discussed below, completely relies on the notion of a human being engaging in creative acts – reflecting “creative choice”. As the Court considered in Painer, “[b]y making those various choices, the author of a portrait photograph can stamp the work created with his ‘personal touch’”.Footnote 34 The point is reinforced in Cofemel: “if a subject matter is to be capable of being regarded as original, it is both necessary and sufficient that the subject matter reflects the personality of its author, as an expression of his free and creative choices”.Footnote 35

Also, according to the CJEU, the exclusive harmonised rights accorded to the author in the InfoSoc Directive necessarily attach to a human creator, not a legal entity such as a film producer or publisher.Footnote 36

Perhaps the clearest formulation of this principle comes from Advocate General Trstenjak in her opinion in Painer, where she concluded from the wording of Art. 6 of the Term Directive, that “only human creations are therefore protected, which can also include those for which the person employs a technical aid, such as a camera”.Footnote 37 This conclusion was endorsed by the Court.

Human rights provide additional arguments in support of the proposition that copyright presupposes human authorship.Footnote 38 For example, the Universal Declaration on Human Rights (UDHR) protects the moral and material interests of authors resulting from scientific, literary or artistic production. Given that human rights by definition vest in human beings, the concept of authorship under the UDHR necessarily refers to human authorship.Footnote 39

In sum, the requirement of human intellectual effort excludes from copyright protection output produced without any human intervention.Footnote 40 For example, the aesthetically pleasing flowers of a rose or wings of a butterfly cannot be qualified as works. Likewise, output wholly generated by an AI system without any human intellectual effort is excluded from copyright protection. This requirement does not rule out, however, creations by human authors made with the aid of machines, provided that the human contribution to the output meets the legal standard of originality/creativity, to which we now turn.Footnote 41

2.3 Originality/Creativity

The EU standard of “the author’s own intellectual creation” requires that the subject matter must be (i) “the author’s own”, that is, not copied, and (ii) an “intellectual creation”.Footnote 42 This twofold requirement usually goes by the name of “originality”. As the CJEU, rather circularly, held in Levola Hengelo and Cofemel: “the subject matter concerned must be original in the sense that it is the author’s own intellectual creation”.Footnote 43 In Painer and Funke Medien, the Court clarified that intellectual creation implies originality, which in turn implies making personal,Footnote 44 creative choices.Footnote 45 This was more recently confirmed in CofemelFootnote 46 and Brompton Bicycle.Footnote 47

The Painer decision is particularly instructive, as it concerns subject matter created with the aid of a machine – notably a photographic portrait. According to the CJEU, a portrait photographer

can make free and creative choices in several ways and at various points in its production. […] By making those various choices, the author of a portrait photograph can stamp the work created with his “personal touch”. Consequently, as regards a portrait photograph, the freedom available to the author to exercise his creative abilities will not necessarily be minor or even non-existent.Footnote 48

In Infopaq, a case involving the protection of newspaper articles against unauthorised scanning, the focus of the Court’s originality enquiry is on “the form, the manner in which the subject is presented and the linguistic expression”.Footnote 49 The CJEU clarified that, for literary works, the author’s “free and creative choices” pertain to the selection, sequence and combination of words.Footnote 50 While admitting that words in isolation do not amount to intellectual creation, the Court adds that it is only through “the choice, sequence and combination of [those] words [that] the author [may express] his or her creativity in an original manner and [achieve] a result which is an intellectual creation”.Footnote 51

Originality or creativity do not, however, imply a requirement of artistic merit or aesthetic quality.Footnote 52 EU copyright law protects works of high art as much as it protects more mundane intellectual output, such as simple photographs, industrial designs, databases or computer software. Conversely, as clarified in Cofemel, the fact that a work “may generate an aesthetic effect” is no reason to qualify it as subject matter protected under EU copyright law.Footnote 53 This is an important observation in relation to AI-assisted output, much of which is undeniably of aesthetic value.

This focus on the act of creation in terms of making free and creative choices implies that economic investment cannot, as such, justify protection. In Football Dataco, the Court squarely rejected “significant skill and labour” on the part of the producer of football fixture lists as a relevant factor in assessing originality.Footnote 54 Similarly, in Funke Medien the Court considered “the mere intellectual effort and skill of creating [military status] reports are not relevant in that regard”.Footnote 55

In essence, the EU law requirement of originality is met “if the author was able to express his creative abilities in the production of the work by making free and creative choices”.Footnote 56 In a string of cases the CJEU has had the opportunity to elaborate on the relevant parameters for such creative choices. Importantly, the Court has identified various types of external constraints to creativity: rule-based, Footnote 57 technical Footnote 58 or functional,Footnote 59 and informational.Footnote 60 All these may play a role in the legal assessment of AI-assisted output in distinct cases.

The CJEU does not, however, seem to require that the author’s creativity or personality (“personal stamp”) be objectively discernible in the resulting expression (the output). What appears to be sufficient is that prospective authors exercise their “free and creative choices” and thereby express their personality.Footnote 61 But is that enough – or does the law additionally require that the “creative space” be creatively used, as the ideas are being expressed in the final production? On the face of it, the case-law does indeed suggest the latter. The Court speaks of choices that must be “creative”, and that “[b]y making those various choices, the author of a portrait photograph can stamp the work created with his ‘personal touch’”.Footnote 62 This language suggests that exercising creative freedom in a non-creative way, e.g. by making only obvious choices, would not result in a protected work. On the other hand, as we have seen before, the requirement of originality or creativity does not entail a test of artistic merit or aesthetic quality, or that the work be novel (new).

National courts have dealt with this problem in different ways. For example, the Dutch Supreme Court expressly denies copyright protection to “trivial” or “banal” expression, even under conditions of broad creative freedom.Footnote 63 The copyright cases so far decided by the CJEU do not give much guidance on how to assess the “creativeness” of the act of creating, if at all; nor do they define a minimum standard of creativity.

Early CJEU decisions suggest that if the external constraints allow an author sufficient creative freedom, then the level of creativity actually required by the Court is fairly low.Footnote 64 In Infopaq the Court suggested that even a short (11-word) text fragment might qualify.Footnote 65 On the basis of the reasoning in Painer, the originality of a photographic work is practically a given.Footnote 66 Even in a case concerning run-of-the-mill school portrait photographs, “the freedom available to the author to exercise his creative abilities will not necessarily be minor or even non-existent”.Footnote 67 This suggests that even a combination of fairly obvious choices in the design, execution and editing of an AI-assisted output could suffice.

By contrast, in Funke Medien, the Court (in line with Advocate General Szpunar) expressed serious doubts over whether the military status reports at issue could qualify as “works”, since the standard format of these reports and their purely informational purpose left (too) little room for creative choices.Footnote 68 Even though the Court’s reasoning in Painer and Funke Medien point in different directions, the focus of the CJEU’s originality analysis in both cases is on the availability of creative choice.

2.4 Expression

A fourth prerequisite for copyright protection is that the human creator’s creativity be “expressed” in the final production. The use by the author of their creative freedom must be somehow perceptible in the author’s expression. Ideas that are not given shape or form cannot qualify as “works”. The CJEU has on several occasions confirmed that expression is a sine qua non for copyright protection. Both in Infopaq and in BSA, the Court states that the author must have “express[ed] his creativity in an original manner”.Footnote 69 In Painer, the CJEU observes that, for a work to be original, the author must be able to “express his creative abilities in the production of the work by making free and creative choices”.Footnote 70 Similarly, in Funke Medien the Court opines that “only something which is the expression of the author’s own intellectual creation may be classified as a ‘work’ within the meaning of Directive 2001/29”.Footnote 71 And in Levola Hengelo the Court has underscored that the author’s creative choices must be sufficiently clearly expressed in the interest of legal certainty.Footnote 72

This requirement of expression implies a causal link between an author’s creative act (the exercising of their creative freedom) and the expression thereof in the form of the work produced. But it remains unclear whether and to what extent the original features of the work should (all) be preconceived or premeditated by the author. Indeed, it is fair to assume that the concept of a work as “the author’s own intellectual creation” requires not only human agency or intervention, but also some degree of authorial intent.Footnote 73 If a work must be “created” by a human “author” and subsequently “expressed”, then this notion clearly cannot encompass wholly haphazard acts of nature, such as the shape of a flower or a solidified lava stream.

But does copyright law require specific intent of every original feature of the work, or does overall authorial intent suffice? Assuming that human authorship goes hand in hand with – and often partly relies on – fortuitous expression, such as slapdash paint drippings in a work of art, a requirement that all expressive features of the work be preconceived would be too strict – and not supported by existing law and practice.Instead, general authorial intent is probably enough. That is to say, it is sufficient that the author has a general conception of the work before it is expressed, while leaving room for unintended expressive features.Footnote 74

In the end, the CJEU’s focus on creative choice as the hallmark of intellectual creation suggests that it is the process of creating rather than the ensuing act of expression that is truly decisive for copyright protection, provided there is an attributable connection between the creative process and the expression.Footnote 75 This conclusion is in line with EU law’s rejection of artistic or qualitative merit as a relevant criterion for protection.

In sum, current EU copyright law, as interpreted by the CJEU, leaves room for the protection of AI-assisted output in a wide range of creative fields. As long as the output reflects creative choices by a human being at any stage of the production process, AI-assisted output is likely to qualify for copyright protection as a “work”.

3 Is AI-Assisted Output a “Work”? A Four-Step Test

In the light of the preceding analysis, we shall now examine whether AI-assisted output can qualify as a “work” protected under EU copyright law. Our focus is on output produced by or with the aid of an AI system. This is in line with a clear trend towards the use of general-purpose (“off-the-shelf”) AI software or services for the production of creative content.Footnote 76 In the following we will generally assume a “user” of an AI system, not involved in its development, who produces an artefact with the aid of the system – the AI-assisted output. It is this user, and this artefact, that will be central to our copyright analysis.

As our inquiry into EU copyright law reveals, a four-step test must be met for an AI production to qualify as a “work”:

-

Step 1: Production in literary, scientific or artistic domain;

-

Step 2: Human intellectual effort;

-

Step 3: Originality/creativity (creative choice);

-

Step 4: Expression.

3.1 Step 1: Production in the Literary, Scientific or Artistic Domain

As noted, much AI-assisted output resembles archetypal works, and belongs to “the literary, scientific or artistic domain” without any difficulty. AI systems are capable of generating almost the entire spectrum of types of work mentioned in Art. 2(1) of the Berne Convention, including news articles, poems, musical compositions, paintings, maps, industrial designs, geographical maps, photographs, and films. For these kinds of output, passing this initial test will therefore be unproblematic, assuming the domain requirement is a material prerequisite under EU law at all.

3.2 Step 2: Human Intellectual Effort

In addition, to qualify as a “work”, the AI-assisted output must be the result of human intellectual effort. The criterion of human intervention does not, however, rule out AI production as a matter of course. As the CJEU has clarified in Painer, it is entirely possible to create works of authorship with the aid of a machine or device.

Moreover, if we leave aside the futuristic scenario of a completely autonomous creative robot, AI-assisted output will always go hand in hand with some form of human intervention, be it the development of the AI software, the gathering and choice of training data, the drawing up of functional specifications, supervision of the creative process, editing, curation, post-production, etc. Even if the connection between the human intervention and the AI-assisted output is increasingly remote, at this point in time it is hard to conceive of content that is generated through AI that involves no human agency whatsoever. What is problematic today and for the immediate future is whether, and to what extent, a natural person’s involvement with the AI-assisted output – however remote – is sufficient for it to qualify as an intellectual creation. This brings us to the third criterion.

3.3 Step 3: Originality or Creativity (Creative Choice)

The third and most crucial criterion is originality or creativity. In the words of the CJEU, this test is met “if the author was able to express his creative abilities in the production of the work by making free and creative choices”.Footnote 77 As we have seen, the emphasis here is on the existence (a priori) of sufficient creative space, rather than on the creativity of the production as such.

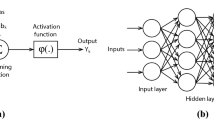

As the Painer case illustrates, creative choices may occur at various levels and in different phases of the creative process: preparation, execution, and finalisation.Footnote 78 Consequently, a creative combination of ideas at distinct stages in the creative process might be enough to qualify the result as a “work” protected under EU copyright. With the Painer decision as inspiration, it is useful to have a closer look at the process of creating works with the aid of AI systems. As the Painer court has well understood, creativity in machine-aided production may occur in three distinct phases of the creative process, which we propose to label “conception”, “execution” and “redaction”.Footnote 79 The figure below provides a simplified diagram of this iterative creative process (Fig. 1).

The conception phase involves creating and elaborating the design or plan of a work. This phase goes beyond merely formulating the general idea for a work.Footnote 80 It requires a series of fairly detailed design choices on the part of the creator: choice of genre, style, technique, materials, medium, format, etc. It also involves conceptual choices relating to the substance of the work: subject matter (news article, portrait), plot (novel, film), melodic idea (musical work), functional specifications (software, databases), etc.Footnote 81 As the CJEU has clarified in Painer, creative choices at this pre-production stage are important factors in a finding of originality of the final production.

In the case of output created with the aid of machine learning (ML) algorithms, above and beyond the design choices identified above, additional conceptual choices may involve the choice of AI system (e.g. the type and characteristics of the models used), as well as the selection and “curation” of input data (e.g. in the labelling of training data) and other parameters.Footnote 82 With AI-assisted output most of these conceptual choices will be exercised by human actors. The AI system at this stage has no role in the creative process other than acting as an external constraint limiting the designer’s creative possibilities.

The execution phase involves, in simple terms, converting the design or plan into what could be considered (rough) draft versions of the final work. This phase involves the production of text, the painting of artwork, the notation or first recording of music, the “shooting” of photographs or video, the “coding” of software, etc. With traditional forms of creation, the role of a human author at this execution stage is crucial. The novelist converts the plot for a novel into words, the composer translates musical ideas into notes. From the 19th century onwards, machines have played an increasingly important auxiliary role in this creative phase. Photographs and films cannot be made without cameras, music not recorded without recording devices, etc. Nevertheless, the human author has always stayed in full control of the execution phase. That is to say, the role of the machine was essentially that of a tool in the creative process.

With AI-assisted creation this has arguably changed, in degree if not in nature. ML systems can be instructed and trained to perform complex tasks and produce sophisticated output in ways that the user of the system will not be able to (precisely) preconceive, understand or explain. From the user’s perspective, this creates the impression of an autonomously operating system: one that the user does not fully control or comprehend, and that strains the classification of an AI system as a “tool”. This is particularly true for Deep Learning systems, where the architecture based on several layers of neural networks greatly increases the distance between the user and the machine during the execution phase.Footnote 83

Whereas some AI systems are capable of generating highly sophisticated, “work-like” content at this stage of the creative process, the quality of the output should not be mistaken for proof of “creativity”. What is essential for our copyright analysis is human creativity.

Finally, the redaction phase involves processing and reworking the draft versions produced in the execution phase into a finalised cultural product ready to be delivered to a publisher or other intermediary, or directly to the market. This final phase may involve a wide range of activities, depending on the genre and medium of the product. These include extensive rewriting, editing, correction, formatting, framing, cropping, colour correction, refinement and all sorts of (other) “post-production” activities that are necessary to give the final touch to the product before it is published and marketed.

Redaction is an underestimated but important, final stage in the creative process, allowing the human author many additional creative choices. As the CJEU has explained in Painer, this final phase of the creative process may involve a variety of creative choices.Footnote 84 Indeed, depending on the circumstances, creative choice in the redaction phase may even suffice for a finding of originality of the entire product. For example, in a case involving geographical maps directly created on the basis of unprotected satellite photographs, a French court of appeal held that the maps qualified for copyright protection because they were “the result of personalised implementation of a complex technology by a process of transformation and improvement of choices, in particular colours, contrasts and luminosity”.Footnote 85

With AI-assisted output this has not fundamentally changed. Even a largely autonomously operating AI system will normally not deliver output that is immediately ready for publication or commercial use. More likely, the output produced by the AI system in the execution phase will require redaction by human actors, especially when it is intended for commercial exploitation. For example, a professional musician using an AI music composer such as AIVA or MuseNet would probably rework and edit output generated by the AI system before finalising the composition.Footnote 86

Even so, not all AI-assisted production will call for extensive redaction. For example, translation machines such as DeepL and Google Translate generate output that is almost ready to use. Nevertheless, here too some human redaction will be required to convert the output into a useful and potentially marketable professional translation. Indeed, DeepL allows its users virtually endless creative freedom in selecting and rephrasing the wording and ordering of each (part of) the translated text.

In some cases, the redaction role of the human user will be reduced to that of selecting or refusing ready-made output generated by the AI system. This raises an interesting question from a copyright perspective. Clearly, the mere act of selecting may be one of many factors contributing to a finding of originality. But what if selecting one AI output from several is the only choice left to the user? Like many other questions raised by AI, this is not a novel issue.

In the past, the emergence of non-traditional art forms such as the ready-mades created by conceptualist artists, have triggered similar questions. What is it that elevates a pre-existing artefact such as a prefabricated urinalFootnote 87 or a bicycle wheelFootnote 88 to a work of art – and, by implication, to a work of authorship? According to Swiss copyright scholar Kummer, the decisive creative act here is converting the (in itself unprotectable) idea of a “ready-made” into copyright protected expression by presenting the artefact (the objet trouvé) as a work of art.Footnote 89 Kummer’s “presentation theory” implies that the mere act of selecting a pre-existing object suffices to convert the object into a work. While Kummer’s theory has been embraced by some copyright scholars, it remains controversial.Footnote 90 In any case, personal selection undoubtedly contributes to a finding of originality in AI-assisted output.

As the preceding discussion reveals, the use of highly advanced AI systems in the production of cultural goods does not imply that human beings have totally surrendered their vital role in the creative process to machines. Whereas the human creator has been partly or largely replaced by the machine at the execution stage of creative production, the human role remains essential at the conception stage, and may have become even more important than before at the redaction stage – given that much AI-assisted output will probably require more redactional work than rough drafts produced by human beings. This leaves both the design choices in the conception phase and the editing and post-production choices in the redaction phase for human authors.

Moreover, it is important to realise that the three-phase creative process described above is simply a model to analyse and explain the authorial choices that contribute to a finding of originality. In reality, the creative process will be iterative. The execution phase will often yield unexpected results that inspire conceptual changes. Redaction may also inspire new ideas that feed back to the conceptual level. In the light of the CJEU’s reasoning in Painer regarding machine-aided creation, which designates both conceptual choices and post-production decisions as relevant factors in the originality analysis, these choices should in many cases be sufficient for a finding of originality in AI-assisted output.Footnote 91

This conclusion is in line with copyright rules in many national laws that allocate authorship to the person that “masterminds” (conceives) and closely supervises the execution of a work by others, without that person materially contributing to the execution phase of creation.Footnote 92 In the words of Professor Ginsburg, “authorship places mind over muscle: the person who conceptualises and directs the development of the work is the author, rather than the person who simply follows orders to execute the work. Most national copyright laws agree that mere execution does not make one an author. An “author” conceives of the work and supervises or otherwise exercises control over its execution”.Footnote 93

While the CJEU has not itself pronounced on the issue of computer-generated productions, there is some case-law at the national level that supports our general conclusion. For example, the Paris court of first instance has held that in the case of “computer-assisted musical composition, when it involves human intervention, the choice of the author [...] leads to the creation of original works”.Footnote 94 In the same vein, the Bordeaux Court of Appeal opined “that a work of the mind created by a computer system can benefit from the rules protecting copyright, provided that it reveals even in a minimal way the originality that its creator wanted to bring”.Footnote 95

3.4 Step 4: Expression

The fourth part of our four-step test of copyright protection is that the human creator’s creativity be “expressed” in the final production. As previously discussed, we derive from this criterion a prerequisite of general authorial intent: the human author must have a general conception of the work before it is expressed, while leaving room for unintended expressive features.

Prima facie, this requirement might present an obstacle for AI-assisted output. Due to the “black box” characteristic of ML systems, the human author in charge of designing the output in the conception phase will not be able to precisely predict or explain the outcome of the execution phase. This, however, need not rule out “work” status of the final output, if such output stays within the ambit of the author’s general authorial intent. Moreover, even completely unpredicted, non-explainable, quasi-random AI-assisted output might still be converted into a protected “work” in the redaction phase.

What “expression” does not require is that courts engage in an assessment of the work’s creative merit, aesthetic value or cultural importance. As the case-law of the CJEU suggests, it is sufficient for a work to be the expression of free creative choices.

3.5 Borderline Cases

The preceding analysis does not imply that every AI-assisted output will unconditionally qualify as a copyright-protected work under EU copyright standards. Much will depend on the facts and circumstances of a case. While sophisticated art created with the aid of an AI system, such as The Next Rembrandt portrait, will necessarily involve important human creative input at several stages of the creative process, this may not be the case for more mundane AI-assisted output such as weather forecasts and news reports.

In extreme cases, the AI system will leave its users no meaningful choice beyond pushing a few buttons. Such cases are evident in the domain of natural language generation, such as the GP-T2 and GP-T3 text generators developed by OpenAI.Footnote 96 One spectacular illustration is Talk to Transformer (now InferKit), which automatically completes a text based on a text fragment (prompt) supplied by the user.Footnote 97 Somewhat similar tools are Deep AI’s Text Generation APIFootnote 98 and StoryAI.Footnote 99 Recently, OpenAI has begun to experiment with applying the “transformer” model previously used on text to images, by training it with pixels. In such cases, however, except for the user-generated prompt it will be difficult to identify any creative choice by the human user in the conception, execution or redaction phases. Consequently, any AI-assisted output generated by such systems would probably not qualify as a “work”.

4 Authorship of AI Output

4.1 Authorship in General

“Work” and “author” are two sides of the same coin. In copyright law, no work exists without an author. Conversely, if there is no work, there will be no author; the question of authorship will only arise if it has been established that there is a work – an intellectual creation – to which authorship can be attributed. In the case of AI-assisted output that does not qualify as a work, no authorship can exist.

The EU copyright acquis is not instructive on the notion of authorship and relies largely on the Berne Convention.Footnote 100 While the InfoSoc Directive requires Member States to provide rights of reproduction, communication to the public and distribution to “authors”, it does not define this notion. Nevertheless, the CJEU has on various occasions suggested that the notion of “author” is reserved for a human creator, not a legal entity such as a film producer or publisher,Footnote 101 let alone an AI system or a robot.

Only a few provisions in EU copyright law directly address the issue of authorship.Footnote 102 The Computer Programs Directive enshrines the general principle that the author is the natural person who has created a work. However, it grants the Member States discretion to deviate from this principle in their national laws on computer software, by allowing them to designate a “legal person” (e.g. a company) as the “author” of a computer program.Footnote 103 Various other directives contain rules on the authorship of audio-visual (film) works; the most important of these directives is the Term Directive, which designates the principal director as (co-)author of the work.Footnote 104

Most authorship issues are dealt with by national law. If two or more authors collaborate on creating a work and their individual creative contributions cannot be separated, the ensuing production will be a joint work, with each contributor qualifying as co-author.Footnote 105 Additionally, most national laws will require that the co-authors work according to a common design, making the joint work a “concerted creative effort”.Footnote 106 If only one of the collaborators engages in creative choices, with the other collaborator reduced to the role of “amanuensis”, only the creatively acting person will qualify as author, and no joint authorship will ensue. Some national laws in the EU provide for special rules of authorship allocation in the case of works created following the design and under the supervision of an author.Footnote 107

Who then are the authors of AI-assisted creations? Our analysis will focus on situations where multiple persons have a potential claim to authorship. Potential candidates include the developer or programmer of the AI system and the users of the system. For our authorship analysis, we follow the three-phase model of creativity previously developed: conception, execution and redaction.Footnote 108 As we have seen, in the case of artefacts produced with the aid of AI systems, the conception phase and – in many cases – the redaction phase will entail creative choices by human beings that justify a finding of copyright protection for the AI-assisted output. Authorship in such cases is to be attributed to the person or persons individually or collectively engaging in these creative choices. If more than a single author is involved in the process, and the authors collaborate, this will lead to co-authorship, even if the creative contributions occur at different stages of the creative process. For example, the Dutch Supreme Court has held that a stylist who creatively arranged needlework pieces to be photographed for a magazine was a co-author with the photographer of the resulting photographs.Footnote 109

Much of the literature on AI and copyright focuses on the scenario of the AI system producing content with only limited input on the part of the user of the system.Footnote 110 If the role of the user of the system is indeed so constricted that they cannot exercise free choice at any stage of the creative process, the user will not qualify as author of the ensuing production. In such cases, the role of the user is essentially reduced to initiating a prompt (e.g. writing an initial sentence) or “pushing buttons”, as in the case of the AI text generation tools discussed above. Here the user’s role is somewhat comparable to that of a person playing a computer game.Footnote 111 For example, authorship of film footage generated by a person playing the popular video game Grand Theft Auto most likely vests in the developers and animators of the video game – not in the player of the game. Even if the player feels empowered and “in control” of whatever transpires on the computer screen, they lack control over the creative process, and their choices do not amount to creative acts justifying a claim of authorship.Footnote 112

As regards such AI systems, where users are effectively no more than passive “players”, the user clearly does not have a valid claim to authorship in the AI-assisted output (i.e. in anything beyond its initial prompt) – leaving the developer of the AI system as the only candidate for authorship of the AI-assisted output.Footnote 113 Note, however, that a valid authorship claim may only arise if it is established that the output qualifies as a “work” in the first place. In the case of AI text generation tools such a finding, however, seems unlikely. The text generated by the AI system was not preconceived by the designer of the system, nor is it creatively redacted. At best one could argue that the output text is an adaptation (transformation) of the text the user input, of which the user (not the developer) is the author.

Valid authorship or co-authorship claims by developers of AI systems are likely to arise primarily in situations where developers and users collaborate on AI output. The Next Rembrandt project is a good example: the painting that the project eventually produced was the result of close collaboration between AI developers, engineers, and art historians, jointly creating a work of authorship.Footnote 114 If the AI system developer played a creative role in the process, they clearly deserve co-authorship status.

In many if not most cases, however, the developers of AI systems will not collaborate in a material way with the users on generating specific output.Footnote 115 For example, providers of general-purpose AI systems or services will provide users with access to their general AI capabilities, without being involved or having knowledge of the specific output to be created with the aid of their systems. In such cases, instances of (co-)authorship by AI system developers are unlikely to materialise, since, under prevailing copyright doctrine, co-authorship can only arise if the work is the result of a “concerted creative effort”, i.e. if multiple authors collaborate according to a common plan to create a specific work.

Moreover, co-authorship claims by AI developers will also be unlikely for obvious commercial reasons. A developer claiming authorship (or co-ownership) of output generated with the aid of its system would probably not attract many customers. Assuming that AI systems will eventually become standard services or tools in the hands of business or commercial users and individual creators (similar to, e.g., Photoshop or Garage Band), the contractual terms of use of the AI system will probably resolve and preclude any such (co-)authorship claims.Footnote 116 Indeed, the terms of use of the popular DeepL AI-powered translation service expressly disclaim any authorship or copyright in relation to content produced by its users with the aid of DeepL.Footnote 117

In the EU, allocating authorship to developers of AI systems may be further complicated by the divergent treatment of computer programs, databases and other creative content.Footnote 118 Like computer games, AI systems that generate audio-visual content are a mix of computer software, databases and (in some cases) audio-visual works. The authorship of the component parts (software, databases, other works) will rarely coalesce in a single author. It may therefore be problematic to establish (co-)authorship of the output generated by the system in those cases where the AI developer has a valid claim to (co-)authorship, that is, when the developer and the user of the AI system collaborate in producing creative output.

4.2 Presumption of Authorship

Proving or enforcing authorship or copyright ownership of a work may sometimes be difficult in practice. For this reason, many Member States provide for rules that establish a (rebuttable) presumption of authorship or copyright ownership, in that the person indicated on or with the published work as the author is deemed to be the author, unless proven otherwise. The Berne Convention and the Enforcement Directive validate such legal presumptions and allow the person whose name “appear[s] on the work in the usual manner” to instigate infringement procedures.Footnote 119

While these rules are intended to facilitate proof of authorship and ownership, they might in practice be abused to disguise the absence of human authorship by falsely attributing AI-assisted output to a natural person. The issue has been flagged in the literature,Footnote 120 but it remains unclear whether it will amount to a serious problem in practice.

Note that falsely claiming copyright protection – also known as “copyfraud”Footnote 121 – is already a well-known, and growing, problem outside the domain of AI.Footnote 122 The problem is exacerbated by the rise of “copyright trolls” that extort content providers on platforms such as YouTube by threatening to trigger the notice-and-take-down procedures that these platforms (automatically) apply.Footnote 123 In the United States, the fraudulent use of copyright notice is criminally punishable under the U.S. Copyright Act.Footnote 124 In most EU Member States, there are no similar provisions; nor does the EU Enforcement Directive deal with fraudulent authorship claims.Footnote 125

4.3 British and Irish Rules on Copyright Protection of Computer-Generated Works

In some copyright laws of the British tradition – including in the UK, Ireland, New Zealand, and South Africa – the requirement of human authorship has been circumvented by establishing the authorship of “computer-generated works” in cases where no human authorship can be established.Footnote 126 Under these regimes, authorship – and by implication copyright ownership – is accorded to the person who undertook the arrangements necessary for its creation.

For example, the Copyright and Related Rights Act 2000 of Ireland defines “computer-generated”, in relation to a work, as meaning “that the work is generated by computer in circumstances where the author of the work is not an individual”.Footnote 127 The Irish Act proceeds to define as “author”, “(f) in the case of a work which is computer-generated, the person by whom the arrangements necessary for the creation of the work are undertaken”.Footnote 128

The UK provisions that inspired the Irish regime are similar, but not identical.Footnote 129 If the existence of a “work” is conditional upon human authorship, this statutory language seems to suggest that the British and Irish regimes attribute authorship to output that would not qualify as an original “work” according to EU copyright law standards. Whether that is, indeed, the correct reading of these provisions, is, however, still unclear. Since the introduction of the regime on computer-generated works in UK law in 1988, this has led to just a single court decision, which has not clarified this issue.Footnote 130

If the British regime indeed protects “authorless” computer-generated works, this would imply that AI-assisted output that does not meet the standard of originality (and therefore is without an “author”) could nonetheless be accorded copyright protection under UK and Irish law, with the producer (“the person by whom the arrangements necessary for the creation of the work are undertaken”) as its author and copyright owner. Not surprisingly, the British and Irish regimes have been criticised as being incompatible with EU copyright standards.Footnote 131 Indeed, a national rule that accords copyright protection to subject matter that does not meet the standard of “the author’s own intellectual creation” is hard to reconcile with CJEU case-law that implies that the notion of a “work” is fully harmonised and therefore does not allow national laws to accord copyright protection under more lenient conditions.Footnote 132

5 Conclusions

As our inquiry into EU copyright law reveals, four interrelated criteria are to be met for AI-assisted output to qualify as a protected “work”: the output is (1) in relation to “production in the literary, scientific or artistic domain”; (2) the product of human intellectual effort; and (3) the result of creative choices that are (4) “expressed” in the output. Whether the first step is established EU law is uncertain. Since most AI artefacts belong to the “literary, scientific or artistic domain” anyway, and are the result of at least some “human intellectual effort”, however remote, in practice the focus of the copyright analysis is on steps 3 and 4.

Based on an analysis of the CJEU’s case-law, we conclude that the core issue is whether the AI-assisted output is the result of human creative choices that are “expressed” in the output. In line with the Court’s reasoning in the Painer case, we distinguish three distinct phases of the creative process in AI-assisted production: “conception” (design and specifications), “execution” (producing draft versions) and “redaction” (selecting, editing, refinement, finalisation).

While AI systems play a dominant role in the execution phase, the role of human authors at the conception stage often remains essential. Moreover, in many instances, human beings will also oversee the redaction stage. Depending on the facts of the case, this will allow human beings sufficient overall creative choice. Assuming these choices are expressed in the final AI-assisted output, the output will then qualify as a copyright-protected work. By contrast, if an AI system is programmed to automatically execute content without the output being conceived or redacted by a person exercising creative choices, there will be no “work”.

Due to the “black box” nature of some AI systems, persons in charge of the conception phase will sometimes not be able to precisely predict or explain the outcome of the execution phase. But this does not present an obstacle to the “work” status of the final output if that output stays within the ambit of the person’s general authorial intent.

Authorship status will be accorded to the person or persons that have creatively contributed to the output. In most cases this will be the user of the AI system, not the AI system developer, unless the developer and user collaborate on a specific AI production, in which case there will be co-authorship. If “off-the-shelf” AI systems are used to create content, co-authorship claims by AI developers will also be unlikely for merely commercial reasons, since AI developers will normally not want to burden customers with downstream copyright claims. We therefore expect this issue to be clarified in the contractual terms of service of providers of such systems.

In conclusion, we believe that the EU copyright framework is generally suitable and sufficiently flexible to deal with the current challenges posed by AI-assisted creation. Producers of AI-assisted output will in many cases enjoy copyright protection. Moreover, “authorless” AI output might still qualify for protection against misappropriation under less demanding IP regimes, such as neighbouring rights and sui generis database protection,Footnote 133 or other doctrines such as trade secrets and unfair competition.Footnote 134 In this light, regulatory intervention to extend copyright protection beyond the current EU rules would be justified only if solid empirical economic analysis were to reveal that the absence of protection harms overall economic welfare in the EU.

Notes

The Next Rembrandt, www.nextrembrandt.com.

See, e.g., Gervais (2019), p. 19.

See Boyden (2016), p. 377; Bridy (2016), p. 395; Bridy (2011), p. 1; Craig and Kerr (2019); Deltorn and Macrez (2018); Denicola (2016), p. 251; Gervais (supra note 3); Ginsburg and Budiardjo (2019), p. 343; Grimmelmann (2017), p. 403; Grimmelmann (2016), p. 657; Guadamuz (2017), p. 169; Kaminski (2017); Ramalho (supra note 4); Ricketson (1991), p. 1. Gervais (2020), p. 117; Ginsburg (2018), 131; Spindler (2019), p. 1049.

See Hugenholtz et al. (2020), and literature cited therein.

See, e.g., Drexl et al. (2019).

See, for a recent overview, Jędrzej Niklas and Lina Dencik, “European Artificial Intelligence Policy: Mapping the Institutional Landscape” (DATAJUSTICE 2020) Working Paper DATAJUSTICE project. For a gateway to the multiple EC initiatives in this area, see European Commission, Strategy, Shaping Europe’s digital future, Policies, “Artificial intelligence”: https://ec.europa.eu/digital-single-market/en/artificial-intelligence. The work of research services associated with the EP and EC – e.g. the EPRS and the JRC – is not detailed in this section but is referred to throughout the text, where directly relevant. Among the most relevant recent work in this respect, see Iglesias Portela et al. (2019); Hamon et al. (2020); Delipetrev et al. (2020).

Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council Laying down harmonised rules on Artificial Intelligence (Artificial Intelligence Act) and amending certain Union Legislative Acts COM/2021/206 final (hereafter AI Act proposal).

Independent High-Level Expert Group on AI set up by the European Commission, “A Definition of AI: Main Capabilities and Disciplines” (2019).

Art. 3(1) AI Act proposal.

Annex I and Art. 3(2) AI Act proposal.

Hugenholtz et al. (supra note 7).

European Commission, “Tapping the EU's innovation potential. An action plan on intellectual property to support EU recovery and resilience”, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, Brussels, 25 November 2020, COM (2020), p. 760.

See EC, “Artificial Intelligence for Europe”, Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions, COM/2018/237 final, 25 April 2018. p. 15 (footnote 52); EP, “Resolution on a comprehensive European industrial policy on artificial intelligence and robotics”, (2018/2088 (INI)), 12 February 2019; and European Parliament resolution of 20 October 2020 on intellectual property rights for the development of artificial intelligence technologies (2020/2015 (INI)), para. 15. NB also relevant initiatives at international level from WIPO. See, e.g., WIPO, “WIPO Technology Trends 2019: Artificial Intelligence”, https://public.ebookcentral.proquest.com/choice/publicfullrecord.aspx?p=5982426 accessed 4 May 2020; WIPO, “Revised Issues Paper on Intellectual Property Policy and Artificial Intelligence” (WIPO 2020a, b), https://www.wipo.int/meetings/en/doc_details.jsp?doc_id=499504 accessed 29 May 2020.

For a discussion of neighbouring rights protection for AI-assisted output, see Hugenholtz et al. (supra note 7), pp. 88–95.

Case C-145/10 – Eva-Maria Painer (2011) ECLI:EU:C:2011:798 (Painer); Case C-604/10 – Football Dataco Ltd and Others v. Yahoo! UK Ltd and Others (2012) ECLI:EU:C:2012:115 (Football Dataco).

See UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (as updated), Sec. 178 (on minor definitions: “‘computer-generated’, in relation to a work, means that the work is generated by computer in circumstances such that there is no human author of the work”); Copyright and Related Rights Act 2000 (Ireland), Sec. 2 (“‘computer-generated’, in relation to a work, means that the work is generated by computer in circumstances where the author of the work is not an individual”).

Directive 2006/116/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 December 2006 on the term of protection of copyright and certain related rights (codified version) (Term Directive).

See also Recital 16 Term Directive: “A photographic work within the meaning of the Berne Convention is to be considered original if it is the author’s own intellectual creation reflecting his personality, no other criteria such as merit or purpose being taken into account.”

See Art. 9(1) TRIPS and Art. 3 WCT.

See, e.g., Case C-277/10 – Martin Luksan v. Petrus van der Let (2012) ECLI:EU:C:2012:65 (Luksan), para. 59, and Case C-310/17 – Levola Hengelo BV v. Smilde Foods BV (2018) ECLI:EU:C:2018:899 (Levola Hengelo), paras. 38–39.

Art. 1(3) Directive 2009/24/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 23 April 2009 on the legal protection of computer programs (Codified version) (Computer Programs Directive); Art. 3(1) Directive 96/9/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 March 1996 on the legal protection of databases (as consolidated); Art. 6 Term Directive; Art. 14 Directive (EU) 2019/790 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 17 April 2019 on copyright and related rights in the Digital Single Market and amending Directives 96/9/EC and 2001/29/EC (CDSM Directive) (on works of visual art in the public domain).

Case C-05/08 – Infopaq International v. Danske Dagblades Forening (2009) ECLI:EU:C:2009:465 (Infopaq).

Case C-310/17 – Levola Hengelo; Case C-469/17 – Funke Medien NRW GmbH v. Bundesrepublik Deutschland (2019) ECLI:EU:C:2019:623 (Funke Medien); Case C-683/17 – Cofemel - Sociedade de Vestuário SA v. G-Star Raw CV (2019) ECLI:EU:C:2019:721 (Cofemel); Case C-833/18 – SI and Brompton Bicycle Ltd v. Chedech / Get2Get (2020) ECLI:EU:C:2020:461 (Brompton Bicycle).

See, e.g., Dietz (1993).

Joined Cases – Football Association Premier League Ltd and Others v. QC Leisure and Others (C-403/08) and Karen Murphy v. Media Protection Services Ltd (C-429/08) (2011) ECLI:EU:C:2011:631 (Premier League), para. 98.

van Gompel (2014), p. 106.

Case C-310/17 – Levola Hengelo, para. 40.

Art. 2(6) Berne Convention (“protection shall operate for the benefit of the author”).

See Ramalho (2019), p. 11.

Case C-145/10 – Painer, para. 92.

Case C-683/17 – Cofemel, para. 30.

Case C-277/10 – Luksan; Case C-572/13 – Hewlett-Packard Belgium SPRL v. Reprobel SCRL (2015) ECLI:EU:C:2015:750 (Reprobel). See infra discussion of authorship and ownership at 4.1.

Opinion AG Trstenjak in Case C-145/10 – Painer, para. 121 (our emphasis).

Art. 27 UDHR. See Gervais, “The Machine As Author” (supra note 3), p. 30.

Art. 27 (2) UDHR.

The Copyright Office of the U.S.A. refuses to register copyright claims in respect of “works produced by a machine or mere mechanical process that operates randomly or automatically without any creative input or intervention from a human author” if it determines that a human being did not create the work. See USPTO, Compendium of U.S. Copyright Office Practices § 101 (3rd edn. 2017). Online: https://www.copyright.gov/comp3/, Arts. 306 and 313(2).

See Ginsburg (supra note 31), p. 1074: “the participation of a machine or device, such as a camera or a computer, in the creation of a work need not deprive its creator of authorship status, but the greater the machine’s role in the work’s production, the more the ‘author’ must show how her role determined the work’s form and content.”

Case C-310/17 – Levola Hengelo, para. 36. See also Case C-683/17 – Cofemel, para. 29.

See Term Directive (version 93/98), recital 17: “a […] work […] is to be considered original if it is the author’s own intellectual creation reflecting his personality”.

Note that US courts and doctrine also focus on “creative choice”. See Gervais, “The Machine As Author” (supra note 3), pp. 41–42.

Case C-683/17 – Cofemel, para. 30.

Case C-833/18 – Brompton Bicycle, para. 23.

Case C-145/10 – Painer, paras. 90–93.

Case C-05/08 – Infopaq, para. 44.

Ibid. para. 45.

See also Case C-469/17 – Funke Medien, para. 23.

van Gompel (supra note 29), p. 99. See, e.g., Computer Programs Directive, recital 8: “In respect of the criteria to be applied in determining whether or not a computer program is an original work, no tests as to the qualitative or aesthetic merits of the program should be applied.” See also Ramalho (supra note 33), p. 7.

Case C-683/17 – Cofemel, para. 54.

Case C-604/10 – Football Dataco, para. 42: “On the other hand, the fact that the setting up of the database required, irrespective of the creation of the data which it contains, significant labour and skill of its author, as mentioned in section (c) of that same question, cannot as such justify the protection of it by copyright under Directive 96/9/EC, if that labour and that skill do not express any originality in the selection or arrangement of that data.”

Case C-469/17 – Funke Medien, para. 23.

Ibid. para. 19; Case C-145/10 – Painer, paras 87–88.

Joined Cases C-403/08 and C-429/08 Premier League, para. 98.

Case C-393/09 – Bezpečnostní softwarová asociace – Svaz softwarové ochrany v. Ministerstvo kultury (2010) ECLI:EU:C:2010:816 (BSA), paras. 49–50. For a comment on this case, see Vousden (2011), p. 728.

Case C-833/18 – Brompton Bicycle, para. 26. For an analysis of the case see Derclaye (2020).

Case C-469/17 – Funke Medien, para. 24. See Leistner (2019) p. 720 (pointing out that the CJEU’s decision might affect copyright protection of AI-generated news reports).

See Case C-145/10 – Painer, para. 92: “By making those various choices, the author of a portrait photograph can stamp the work created with his ‘personal touch’”.

Case C-145/10 – Painer, para. 92.

Supreme Court (The Netherlands) Zonen Endstra v. Nieuw Amsterdam (2008) ECLI:NL:HR:2008:BC2153, HR 30.05.2008, NJ 2008, 556. See van Gompel (supra note 29).

van Gompel (supra note 29), p. 100.

Case C-05/08 – Infopaq.

For a critique of this approach, see van Gompel (supra note 29), p. 121.

Case C-145/10 – Painer, para. 93.

Case C-469/17 – Funke Medien, para. 23.

Case C-05/08 – Infopaq, para. 45 Case C-393/09 – BSA, para. 50.

Case C-145/10 – Painer, para. 89.

Case C-469/17 – Funke Medien, para. 20.

Case C-310/17 – Levola Hengelo, para. 40.

But see Supreme Court (The Netherlands) Zonen Endstra v. Nieuw Amsterdam (2008) ECLI:NL:HR:2008:BC2153, HR 30.05.2008, NJ 2008, 556 (creative intent not required: whether or not a work is the result of a creative act should be judged merely on the basis of the creative production as such).

Ginsburg and Budiardjo (supra note 6), p. 363; Burk (2020).

See Senftleben and Buijtelaar (supra note 4).

This trend is described e.g. in Hugenholtz et al. (supra note 7).

Case C-469/17 – Funke Medien, para. 19; Case C-145/10 – Painer, paras. 87–88.

Ramalho (supra note 33), p. 7.

See Ginsburg and Budiardjo (supra note 6). (discussing “detailed conception” and controlled execution). See also Ramalho (supra note 33), p. 7. (distinguishing “preparation”, execution” and “final” phases in analysis of Painer judgment).

Ginsburg and Budiardjo (supra note 6), pp. 347–348.

van Gompel (supra note 29), p. 112 ff. See, e.g., Court of Brussels, 23 May 2017 (Diplomatic card v. Forax), I.R.D.O., 2017, 204 (functional and technical specifications protected as part of computer program). But see Supreme Court (Netherlands) Diplomatic Card v. Forax, 19 January 2018, ECLI:NL:HR:2018:56, NJ 2018/237 (technical specifications do not qualify as “preparatory design material” if programming requires subsequent “creative steps”).

See Dreier (1992), pp. 869–888.

Hugenholtz and others (supra note 7).

Case C-145/10 – Painer.

Court of Appeal Riom, 14 May 2003, D. 2003, somm. 2754, obs.Sirinelli, quoted by A. Lucas and P. Kamina, in: International Copyright Law & Practice, France, § 2[2][b].

See AIVA, https://www.aiva.ai/ and OpenAI, Musenet, https://openai.com/blog/musenet/.

Tate, Marcel Duchamp, Fountain, https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artworks/duchamp-fountain-t07573.

Tate, Marcel Duchamp, Bicycle Wheel, https://www.moma.org/learn/moma_learning/marcel-duchamp-bicycle-wheel-new-york-1951-third-version-after-lost-original-of-1913/.

Kummer (1968), p. 193 ff.

See AIPPI German Delegation, “Copyright in Artificially Generated Works” (2019) Copyright in artificially generated works National Report, https://aippi.soutron.net/Portal/Default/en-GB/RecordView/Index/254, accessed 15 April 2021. In favour, see Dreier (supra note 82). Lauber-Rönsberg (2019), pp. 244, 245.

Dreier (supra note 82), p. 882.

Ginsburg and Budiardjo (supra note 6), p. 360. See also Ginsburg (supra note 31), p. 1072. For example, Art. 6 Dutch Copyright Act provides: “Where a work has been made according to the design by and under the direction and supervision of another person, that person is considered to be the author of the work.” See Seignette (2012), p. 123; Spoor et al. (2019), p. 31 ff.

Ginsburg (supra note 31), p. 1072.

Paris District Court (France), 5 July 2000, No. 97/24872 (Matt Cooper v. Ogilvy and Mather).

Bordeaux Court of Appeal (France), 31 January 2005, No. 03/05512.

See Open AI, GPT-2: 1.5B Release (5 November 2019), https://openai.com/blog/gpt-2-1-5b-release/; Brown et al. (2020).

See Talk to Transformer, https://talktotransformer.com. Talk to Transformer has recently been transformed into the paid product InferKit. According to its website, “InferKit offers a web interface and API for AI–based text generators. Whether you’re a novelist looking for inspiration, or an app developer, there’s something for you.” See InferKit, https://inferkit.com/. For a basic explanation of how InferKit’s text generation tool works, see InferKit, Docs, Text Generation https://inferkit.com/docs/generation (“InferKit’s text generation tool creates continuations of any text you give it, using a state-of-the-art neural network. It’s configurable and can produce any length of text on practically any topic.” You can also create custom generators for specific kinds of content.)

DeepAI, Text Generation API, https://deepai.org/machine-learning-model/text-generator (“The text generation API is backed by a large-scale unsupervised language model that can generate paragraphs of text. This transformer-based language model, based on the GPT-2 model by OpenAI, intakes a sentence or partial sentence and predicts subsequent text from that input”) (our emphasis).

See Storyai, About – Q&A, https://storyai.botsociety.io/about (“Write the story you couldn’t quite find the words to complete with this easy to use OpenAI model. Input 40 words to start, and watch what the model comes up with. It’s powered by the GPT-2 774M model released on August 20th 2019 by OpenAI.”)

See Dietz (supra note 27).

Case C-277/10 – Luksan; Case C-572/13 – Reprobel.

Art. 2(1) Computer Programs Directive.

Art. 2(1) Term Directive (“The principal director of a cinematographic or audiovisual work shall be considered as its author or one of its authors. Member States shall be free to designate other co-authors.”)

Goldstein and Hugenholtz (supra note 31), p. 233.

Ibid. See Supreme Court (France) 1st Civil Chamber, 18 October 1994, 164 R.I.D.A. pp. 304, 308 (1995).

For example, Art. 6 Dutch Copyright Act. For French law, see Ginsburg (supra note 31), p. 1072.

See above at 3.

Supreme Court (Netherlands), 1 June 1990 (Kluwer v. Lamoth), Nederlandse Jurisprudentie 1991, p. 377. See also Paris District Court, 6 July 1970, RIDA 190 (1970) (affaire Paris Match). See Ginsburg (supra note 31), p. 1070; (supra note 24).

See, e.g., Gervais, “The Machine As Author” (supra note 3), and references cited therein.

Supreme Court (Cass. Ass. plén.) 7 March 1986, No 84-93509 (Atari Inc. c/ Valadon) and No. 85-91465 (Williams Electronics Inc. c/ Claudie T. et Sté Jeutel), R.I.D.A. 1986, No. 129, 136.

See Ginsburg and Budiardjo (supra note 6) with reference to U.S. cases on computer games.

See, e.g., High Court (England and Wales), Express Newspapers v. Liverpool Daily Post [1985] 1 W.L.R. pp. 1089, 1093 (computer programmer considered author of output generated with tailor-made program). See also AIPPI UK National Group, “Copyright in Artificially Generated Works National Report UK” (AIPPI 2019) 5, https://aippi.soutron.net/Portal/Default/en-GB/RecordView/Index/261, accessed 15 April 2021; and Ginsburg (supra note 31), p. 1074.

See Microsoft reporter, “The Next Rembrandt: Recreating the Work of a Master with AI” (Blurring the lines between art, technology and emotion: The Next Rembrandt, 04 2016) https://news.microsoft.com/europe/features/next-rembrandt/ accessed 15 July 2020.

See Samuelson (supra note 5), pp. 1223–1224.

For a brief overview of the many legal and practical complexities that authorship/ownership claims by AI developers would entail, see CLSPA et al. (2020), p. 39.

DeepL Pro Terms and Conditions, available at https://www.deepl.com/pro-license/. Article 7.5 of DeepL Pro’s terms and conditions provides: “DeepL does not assume any copyrights to the translations made by Customer using the Products. In the event that the translations made by Customer using the Products are deemed to be protected under copyright laws to the benefit of DeepL, DeepL grants to Customer, upon creation of such translations, all excusive, transferable, sublicensable, worldwide perpetual rights to use the translations without limitation and for any existing or future types of use, including without limitation the right to modify the translations and to create derivative works.”

See Federal Supreme Court (Germany) 06.10.2016 – I ZR 25/15, World of Warcraft I, GRUR 2017, p. 266 (“2nd world” game World of Warcraft contains distinct elements (software, graphics, sound) protected by different IP regimes). See also Case C-355/12 – Nintendo Co. Ltd and Others v. PC Box Srl and 9Net Srl (2014) ECLI:EU:C:2014:25 (Nintendo).

Art. 15(1) Berne Convention; Art. 5 Directive 2004/48/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the enforcement of intellectual property rights (as corrected in OJ L 157, 30.4.2004) (Enforcement Directive).

CLSPA, Bensamoun and Farchy (supra note 116), p. 31.

See Wikipedia, “Copyfraud”, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Copyfraud.

See Sag (2015), p. 1105.

See, e.g., Worrall (2020).

Sec. 506(c) and 506(e) U.S. Copyright Act.

Note that according to the proposed Digital Services Act online platforms must suspend users that “frequently provide manifestly illegal content”. Proposal for a Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council on a Single Market for Digital Services (Digital Services Act) and amending Directive 2000/31/EC, COM/2020/825 final, Art. 20.

See Guadamuz (supra note 6) (including a survey of these national laws).

Art. 2(1) Copyright and Related Rights Act 2000 of Ireland.

Art. 21 Copyright and Related Rights Act 2000 of Ireland.

UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (UK, as updated), Sec. 178; Bently et al. (2018), pp. 117–118.

Court of Appeal (England and Wales) Nova Productions Ltd v. Mazooma Games Ltd & Ors (CA) [2007] EWCA Civ 219; 14 March 2007. See also Ramalho (supra note 33), pp. 13–14; Bonadio and McDonagh (2020), p. 112.

See Gonzalez Otero and Quintais (2018) (reporting on the presentation of Professor Lionel Bently); and Bently et al. (supra note 129), p. 118. (“Because the European standard now applies to all works, it must be doubted whether copyright protection (in an European sense) should be regarded as available at all to ‘computer-generated works’. … It seems to follow that no computer-generated work can be protected by copyright in accordance with European Law.”). On the latter point, see also Ginsburg (supra note 6).

See, in particular, Case C-604/10 – Football Dataco.

See Hugenholtz et al. (supra note 7).

References

AIPPI German Delegation (2019) Copyright in artificially generated works. In: Copyright in artificially generated works national report. https://aippi.soutron.net/Portal/Default/en-GB/RecordView/Index/254. Accessed 15 Apr 2021

AIPPI UK National Group (2019) Copyright in artificially generated works national report UK. AIPPI. https://aippi.soutron.net/Portal/Default/en-GB/RecordView/Index/261. Accessed 15 Apr 2021

Bently L et al (2018) Intellectual property law, 5th edn. OUP. https://global.oup.com/ukhe/product/intellectual-property-law-9780198769958?cc=nl&lang=en&. Accessed 15 Jul 2020

Bonadio E, McDonagh L (2020) Artificial intelligence as producer and consumer of copyright works: evaluating the consequences of algorithmic creativity. Intellect Prop Q 2:112

Boyden BE (2016) Emergent works. Columbia J Law Arts 39:377

Bridy A (2011) Coding creativity: copyright and the artificially intelligent author. Stanf Law Rev 5:1

Bridy A (2016) The evolution of authorship: work made by code. Columbia J Law Arts 39:395

Brown TB et al (2020) Language models are few-shot learners. arXiv:2005.14165 [cs]. Accessed 28 Sept 2020

Burk DL (2020) Thirty-six views of copyright authorship, by Jackson Pollock. Houst Law Rev 58. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3570225. Accessed 9 Apr 2021

Butler TL (1982) Can a computer be an author – copyright aspects of artificial intelligence. Hastings Comm Ent L J 4:707

CLSPA, Bensamoun A, Farchy (2020) Mission du CSPLA sur les enjeux juridiques et économiques de l’intelligence artificielle dans les secteurs de la création culturelle. (CLSPA – Conseil Supérieur de la Propriété Littéraire et Artistique 2020). https://www.culture.gouv.fr/Sites-thematiques/Propriete-litteraire-et-artistique/Conseil-superieur-de-la-propriete-litteraire-et-artistique/Travaux/Missions/Mission-du-CSPLA-sur-les-enjeux-juridiques-et-economiques-de-l-intelligence-artificielle-dans-les-secteurs-de-la-creation-culturelle

Craig CJ, Kerr IR (2019) The death of the AI author. In: Osgoode legal studies research paper. https://robots.law.miami.edu/2019/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/Kerr_Death-of-AI-Author.pdf. Accessed 4 May 2020

Delipetrev B et al (2020) AI watch: defining artificial intelligence: towards an operational definition and taxonomy of artificial intelligence. Joint Research Centre. JRC working papers KJ-NA-30117-EN-N. http://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/6cc0f1b6-59dd-11ea-8b81-01aa75ed71a1/language-en. Accessed 4 May 2020

Deltorn J-M, Macrez F (2018) Authorship in the age of machine learning and artificial intelligence. In: The Oxford handbook of music law and policy. OUP. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3261329. Accessed 29 Apr 2020

Denicola R (2016) Ex machina: copyright protection for computer-generated works. Rutgers Univ Law Rev 69:251

Derclaye E (2020) The CJEU decision in Brompton Bicycle – a welcome double rejection of the multiplicity of shapes and causality theories in copyright law. Kluwer Copyright Blog. http://copyrightblog.kluweriplaw.com/2020/06/25/the-cjeu-decision-in-brompton-bicycle-a-welcome-double-rejection-of-the-multiplicity-of-shapes-and-causality-theories-in-copyright-law/. Accessed 8 July 2020

Dietz A (1993) Le Concept d’auteur Selon Le Droit de La Convention de Berne. RIDA 155(01):2–57

Dreier T (1992) Creation and investment: artistic and legal implications of computer-generated works. In: Leser HG, Isomura T (eds) Wege zum japanischen Recht. Festschrift für Zentaro Kitagawa. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin, pp 869–888

Drexl J et al (2019) Technical aspects of artificial intelligence: an understanding from an intellectual property law perspective. Max Planck Inst Innov Compet 11. https://www.ip.mpg.de/en/publications/journals/research-paper-series.html. Accessed 4 May 2020

Fromm FK (1964) Der Apparat Als Geistiger Schopfer. GRUR 304

Gervais D (1991) The protection under international copyright law of works created with or by computers. IIC Int Rev Intellect Prop Compet Law 5:629

Gervais DJ (2019) The machine as author. Iowa Law Rev 105:19